Breast cancer remains a global challenge, causing over six hundred thousand deaths in 2018 [1]. To achieve earlier cancer detection, health organizations worldwide recommend screening mammography, which is estimated to decrease breast cancer mortality by 20–40% [2, 3]. Despite the clear value of screening mammography, significant false positive and false negative rates along with non-uniformities in expert reader availability leave opportunities for improving quality and access [4, 5]. To address these limitations, there has been much recent interest in applying deep learning to mammography [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18], and these efforts have highlighted two key difficulties: obtaining large amounts of annotated training data and ensuring generalization across populations, acquisition equipment, and modalities. Here, we present an annotation-efficient deep learning approach that 1) achieves state-of-the-art performance in mammogram classification, 2) successfully extends to digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT; “3D mammography”), 3) detects cancers in clinically-negative prior mammograms of cancer patients, 4) generalizes well to a population with low screening rates, and 5) outperforms five-out-of-five full-time breast imaging specialists with an average increase in sensitivity of 14%. By creating novel “maximum suspicion projection” (MSP) images from DBT data, our progressively-trained, multiple-instance learning approach effectively trains on DBT exams using only breast-level labels while maintaining localization-based interpretability. Altogether, our results demonstrate promise towards software that can improve the accuracy of and access to screening mammography worldwide.

Despite technological improvements such as the advent of DBT [19], studies that have reviewed mammograms where cancer was detected estimate that indications of cancer presence are visible 20–60% of the time in earlier exams that were interpreted as normal [20, 21, 22]. Misinterpretation rates are significant in part because of the difficulty of mammogram interpretation – abnormalities are often indicated by small, subtle features, and malignancies are only present in approximately 0.5% of screened women. These challenges are exacerbated by the high volume of mammograms (over 40 million per year in the United States alone) and the additional time required to interpret DBT, both of which pressure radiologists to read faster.

Given these challenges, there have been many efforts in developing computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) software to assist radiologists in interpreting mammograms. The rationale behind initial versions of CAD was that even if its standalone performance was inferior to expert humans, it could still boost sensitivity when used as a “second look” tool. In practice however, the effectiveness of traditional CAD has been questioned [23, 24, 25, 26]. A potential reason for the limited accuracy of traditional CAD is that it relied on hand-engineered features. Deep learning relies instead on learning the features and classification decisions end-to-end. Applications of deep learning to mammography have shown great promise, including recent important work where McKinney et al. (2020) [17] presented evidence of a system that exceeded radiologist performance in the interpretation of screening mammograms. Their system was trained and tested on 2D mammograms from the UK and USA, and demonstrated generalization from training on UK data to testing at a USA clinical data site.

Despite such strong prior work, there remains significant room for improvement, especially in developing methods for DBT and demonstrating more widespread generalization. One of the key motivations for developing artificial intelligence (AI) applications for mammography lies in increasing access to screening. Demonstrating that AI performance generalizes to populations with currently low screening rates would be an important initial step towards a tool that could help alleviate scarcity of expert clinicians [27, 28]. Furthermore, AI would ideally demonstrate benefit in extending the window in which many cancers can be detected. Finally, given the rapid rise in the use of DBT for screening and its additional interpretation challenges, developing AI systems for DBT would be particularly impactful. In sum, prior efforts have illustrated the potential of applying AI to mammography, but further robustness and generalization are necessary to move towards true clinical utility.

Both data-related and algorithmic challenges contribute to the difficulty of developing AI solutions that achieve the aforementioned goals. Deep learning models generally perform best when trained on large amounts of highly-annotated data, which is difficult to obtain for mammography. The two most prominent public datasets for mammography are the Digital Database of Screening Mammography (DDSM) [29] and the Optimam Mammography Imaging Database (OMI-DB) [30], both of which consist of 2D data. While relatively small compared to some natural image dataset standards [31], DDSM and OMI-DB both contain strong annotations (e.g., expert-drawn bounding boxes around lesions). As opposed to weak annotations (e.g., knowing only the breast laterality of a cancer), strong annotations are particularly valuable for mammography given its “needle-in-a-haystack” nature. This is especially true for DBT, which can contain over 100 times as many images (or “slices”) as digital mammography (DM) and on which malignant features are often only visible in a few of the slices. This combination of large data size with small, subtle findings can cause deep learning models to memorize spurious correlations in the training set that do not generalize to independent test sets. Strong annotations can mitigate such overfitting, but are costly and often impractical to collect. Nonetheless, many mammography AI efforts rely predominantly on strongly-labeled data and those that use weakly-labeled data often lack a consistent framework to simultaneously train on both data types while maintaining intuitive localization-based interpretability [7, 11, 17, 32].

Here, we have taken steps to address both the data and algorithmic challenges of deep learning in mammography. We have assembled three additional training datasets, focusing especially on DBT, and have developed an algorithmic approach that effectively makes use of both strongly and weakly-labeled data by progressively training a core model in a series of increasingly difficult tasks. We evaluate the resulting system extensively, assessing both standalone performance and performance in direct comparison to expert breast imaging specialists in a reader study. In contrast to other recent reader studies [11, 17], our study involves data from a site that was never used for model training to enable a more fair and generalizable comparison between AI and readers. Altogether, we use five test sets spanning different modalities (DM and DBT), different acquisition equipment manufacturers (General Electric (GE) and Hologic) and different populations (US, UK, and China). Additionally, our reader study investigates different timeframes of “ground truth”: 1) “index” cancer exams, which are typically used in reader studies and are the screening mammograms acquired most recently prior to biopsy-proven malignancy; and 2) what we term “pre-index” cancer exams – screening mammograms acquired a year or more prior to the index cancer exams that were interpreted as normal by the clinician at the time of acquisition.

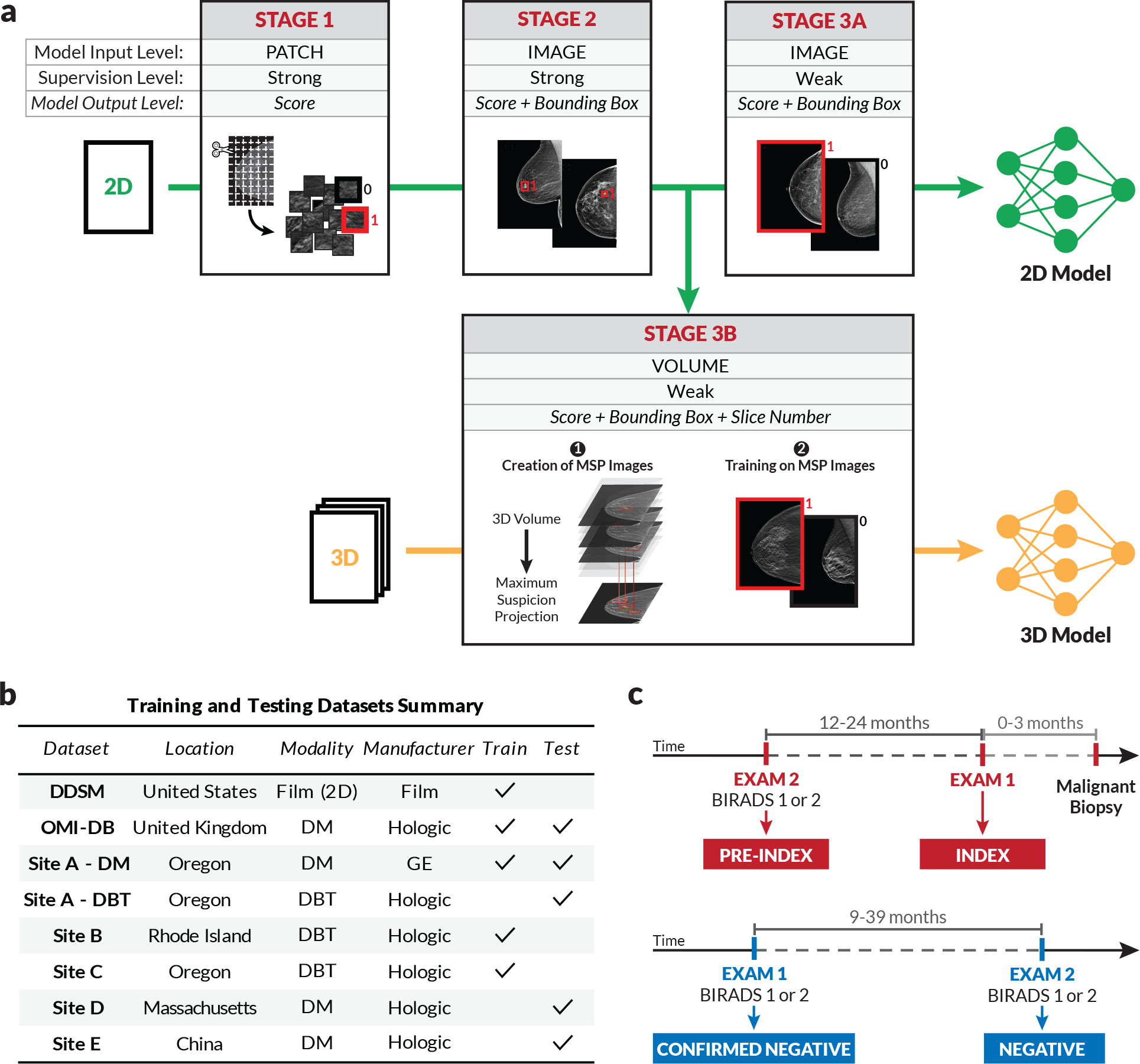

Figure 1 details our model training pipeline, our training and testing data, and our definition of different exam types. In the first step of our approach, we train a convolutional neural network (CNN) to classify whether lesions are present in cropped image patches [15]. Next, we use this CNN to initialize the backbone of a detection-based model which takes an entire image as input and outputs bounding boxes with corresponding scores, where each score indicates the likelihood that the enclosed region represents a malignancy. These first two stages both use strongly-labelled data. In Stage 3A, we train the detection model on weakly-labelled 2D data using a multiple-instance learning formulation where a maximum is computed over all of the bounding box scores. This results in a single image score that intuitively corresponds to the most suspicious region-of-interest (ROI) in the image. Importantly, even though the model at this stage is only trained with image-level labels, it retains its localization-based explainability, mitigating the “black-box” nature of standard classification models. Stage 3B consists of our weakly-supervised training approach for DBT. Given a DBT volume, the strongly-supervised 2D model is evaluated on each slice to produce a set of bounding boxes that are then filtered to retain the highest-scoring box at each spatial location. The image patches defined by the boxes are then collapsed into a single 2D image array, which we term a ‘maximum suspicion projection’ (MSP) image. After creating the MSP images, the strongly-supervised 2D detection model from Stage 2 is then trained on these images using the same multiple-instance learning formulation described above.

Figure 1: Model training approach and data summary.

a) To effectively leverage both strongly and weakly-labeled data while mitigating overfitting, we progressively train our deep learning models in a series of stages. Stage 1 consists of patch-level classification using cropped image patches from 2D mammograms [15]. In Stage 2, the model trained in Stage 1 is used to initialize the feature backbone of a detection-based model. The detection model, which outputs bounding boxes with corresponding classification scores, is then trained end-to-end in a strongly-supervised manner on full images. Stage 3 consists of weakly-supervised training, for both 2D and 3D mammography. For 2D (Stage 3a), the detection network is trained for binary classification in an end-to-end, multiple-instance learning fashion where an image-level score is computed as a maximum over bounding box scores. For 3D (Stage 3b), the model from Stage 2 is used to condense each DBT stack into an optimized 2D projection by evaluating the DBT slices and extracting the most suspicious regions of interest at each x-y spatial location. The model is then trained on these “maximum suspicion projection” (MSP) images using the approach in Stage 3a. b) Summary of training and testing datasets. c) Illustration of exam definitions used here.

Figure 1b summarizes the data sources used to train and test our models. In addition to OMI-DB and DDSM, we use datasets collected from three US clinical sites for training, denoted as Sites A, B, and C. The data used for testing includes test partitions of the OMI-DB and “Site A - DM” datasets in addition to three datasets that were never used for model training or selection. These testing-only datasets include a screening DM dataset from a Massachusetts health system used for our reader study (Site D), a diagnostic DM dataset from an urban hospital in China (Site E), and a screening DBT dataset from a community hospital in Oregon (Site A - DBT). We note that we test on screening mammograms whenever possible, but the low screening rates in China necessitate using diagnostic exams (i.e., those in which the woman presents with symptoms) in the Site E dataset.

As briefly outlined above, we conducted a reader study using both “index” and “pre-index” cancer exams to directly compare to expert radiologists in both regimes. Specifically, we define the index exams as mammograms acquired up to three months prior to biopsy-proven malignancy (Fig. 1c). We define pre-index exams as those that were acquired 12–24 months prior to the index exams and interpreted as negative in clinical practice. Following the BIRADS standard [33], we consider a BIRADS score of 1 or 2 as a negative interpretation and further define a “confirmed negative” as a negative exam followed by an additional BIRADS 1–2 screen. All of the negatives used in our reader study are confirmed negatives.

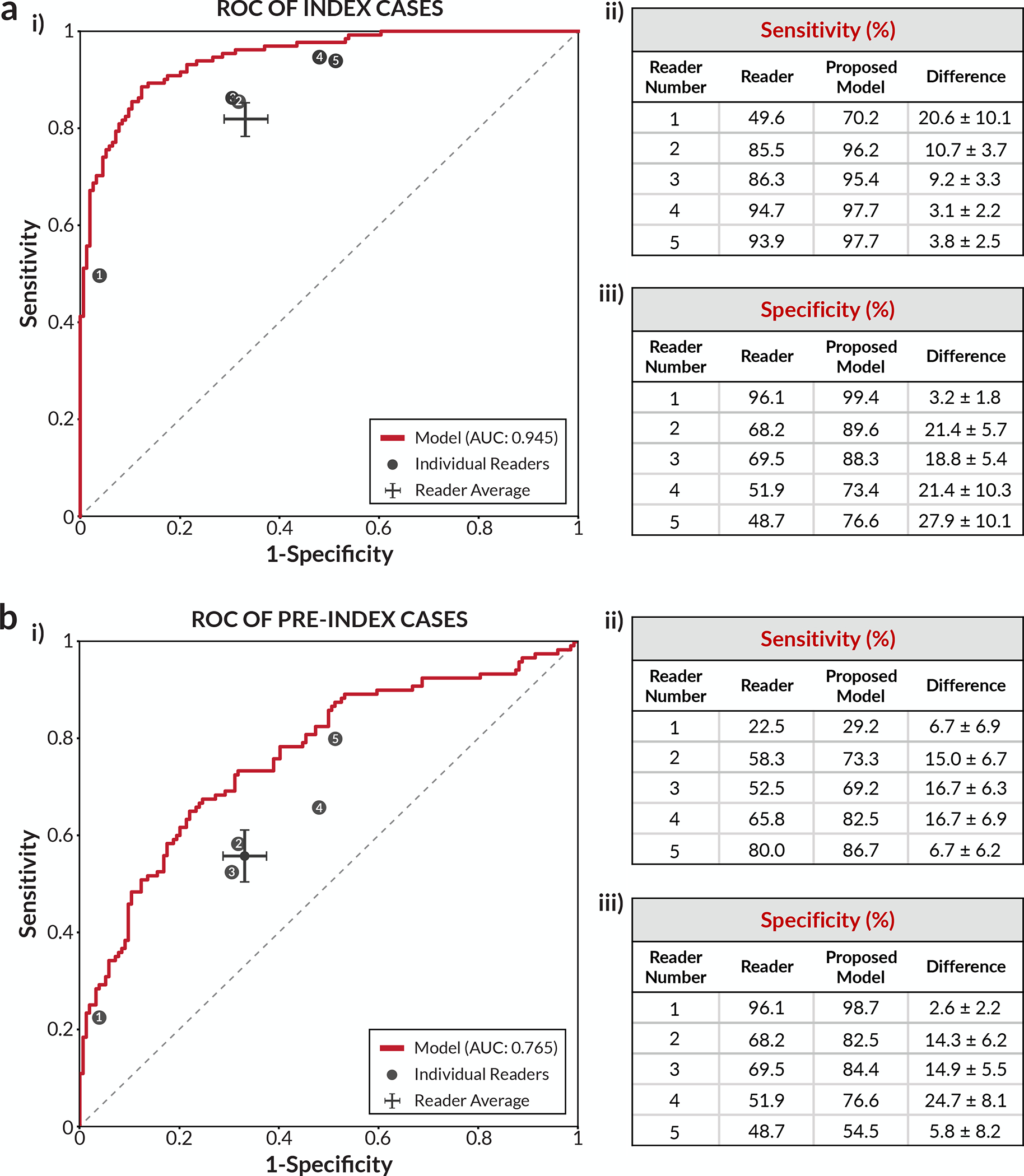

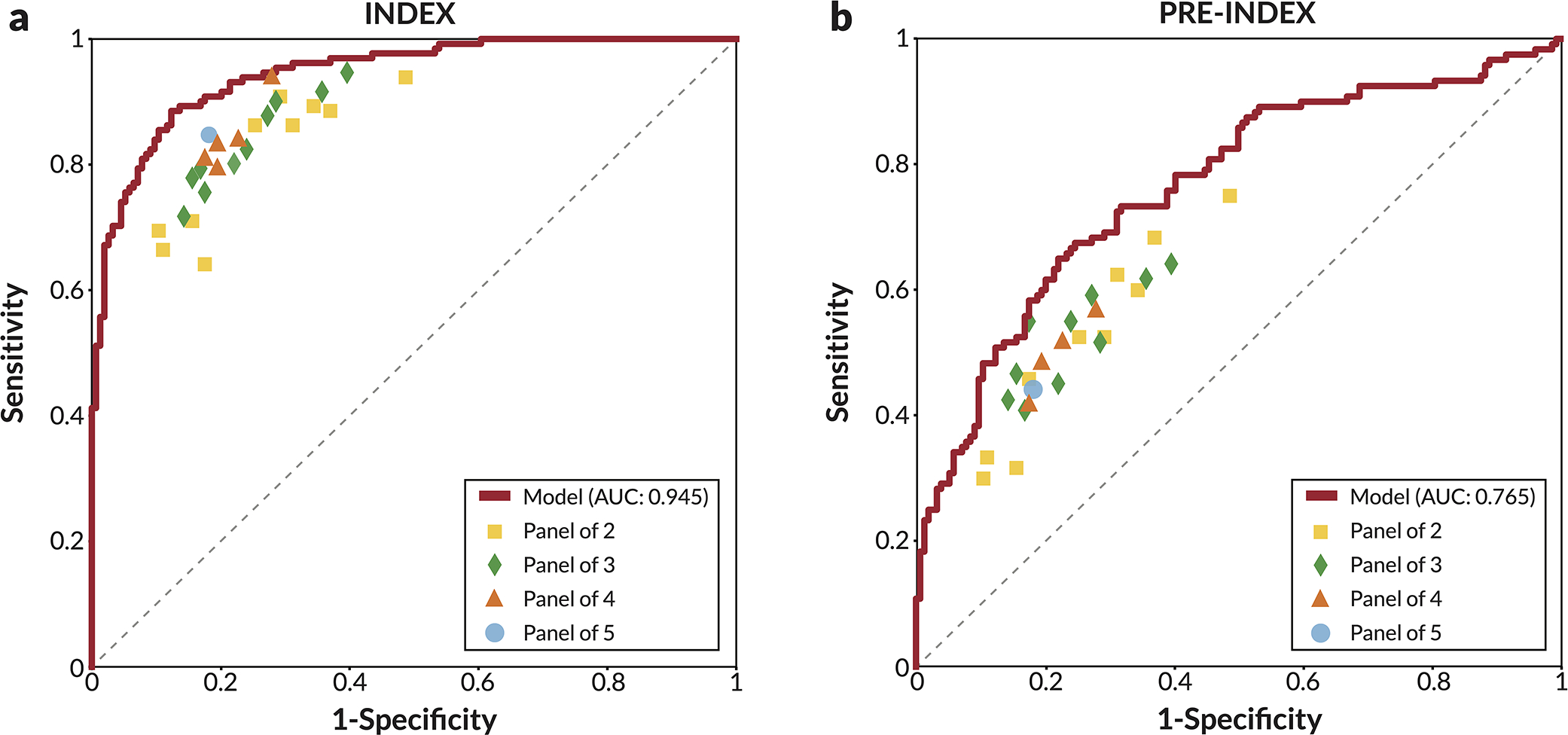

Figure 2a summarizes the results of the “index” component of the reader study. The study involved five radiologists, each fellowship-trained in breast imaging and practicing full-time in the field. The data consisted of screening DM cases retrospectively collected from a regional health system located in a different US state than any of the sources of training data. Figure 2a contains a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot based on case-level performance comparing the readers to the proposed deep learning model on the set of 131 index cancer exams and 154 confirmed negatives. The points representing each reader all fall below the model’s ROC curve, indicating that the model outperformed all five radiologists. At the average reader specificity, the model achieved an absolute increase in sensitivity of 14.2% (95% confidence interval (CI): 9.2–18.5%; p<0.0001). At the average reader sensitivity, the model achieved an absolute increase in specificity of 24.0% (95% CI: 17.4–30.4%; p<0.0001). Reader ROC curves based on a continuous “probability of malignancy” score are also contained in Extended Data Figure 1 and illustrate similar higher performance by the model. Additionally, the model outperformed every simulated combination of the readers (Extended Data Figure 2) and also compares favorably to other recently published models on this dataset [7, 11, 32] (Extended Data Figure 3).

Figure 2: Reader study results.

a) Index cancer exams & confirmed negatives. i) The proposed deep learning model outperformed all five radiologists on the set of 131 index cancer exams and 154 confirmed negatives. Each data point represents a single reader, and the ROC curve represents the performance of the deep learning model. The cross corresponds to the mean radiologist performance with the lengths of the cross indicating 95% confidence intervals. ii) Sensitivity of each reader and the corresponding sensitivity of the proposed model at a specificity chosen to match each reader. iii) Specificity of each reader and the corresponding specificity of the proposed model at a sensitivity chosen to match each reader. b) Pre-index cancer exams & confirmed negatives. i) The proposed deep learning model also outperformed all five radiologists on the early detection task. The dataset consisted of 120 pre-index cancer exams - which are defined as mammograms interpreted as negative 12–24 months prior to the index exam in which cancer was found - and 154 confirmed negatives. The cross corresponds to the mean radiologist performance with the lengths of the cross indicating 95% confidence intervals. ii) Sensitivity of each reader and the corresponding sensitivity of the proposed model at a specificity chosen to match each reader. iii) Specificity of each reader and the corresponding specificity of the proposed model at a sensitivity chosen to match each reader. For the sensitivity and specificity tables, the standard deviation of the model minus reader difference was calculated via bootstrapping.

Figure 2b summarizes the second component of the reader study involving “pre-index” exams from the same patients. Pre-index exams can largely be thought of as challenging false negatives, as studies estimate that breast cancers typically exist 3+ years prior to detection by mammography [34, 35]. The deep learning model outperformed all five readers in the early detection, pre-index paradigm as well. The absolute performances of the readers and the model were lower on the pre-index cancer exams than on the index cancer exams, which is expected given the difficulty of these cases. Nonetheless, the model still demonstrated an absolute increase in sensitivity of 17.5% (95% CI: 6.0–26.2%; p=0.0009) at the average reader specificity, and an absolute increase in specificity of 16.2% (95% CI: 7.3–24.6%; p=0.0008) at the average reader sensitivity. At a specificity of 90% [36], the model would have flagged 45.8% (95% CI: 28.8–57.1%) of the pre-index (e.g., “missed”) cancer cases for additional workup. The model additionally exhibited higher performance than recently published models on the pre-index dataset as well [7, 11, 32] (Extended Data Figure 4).

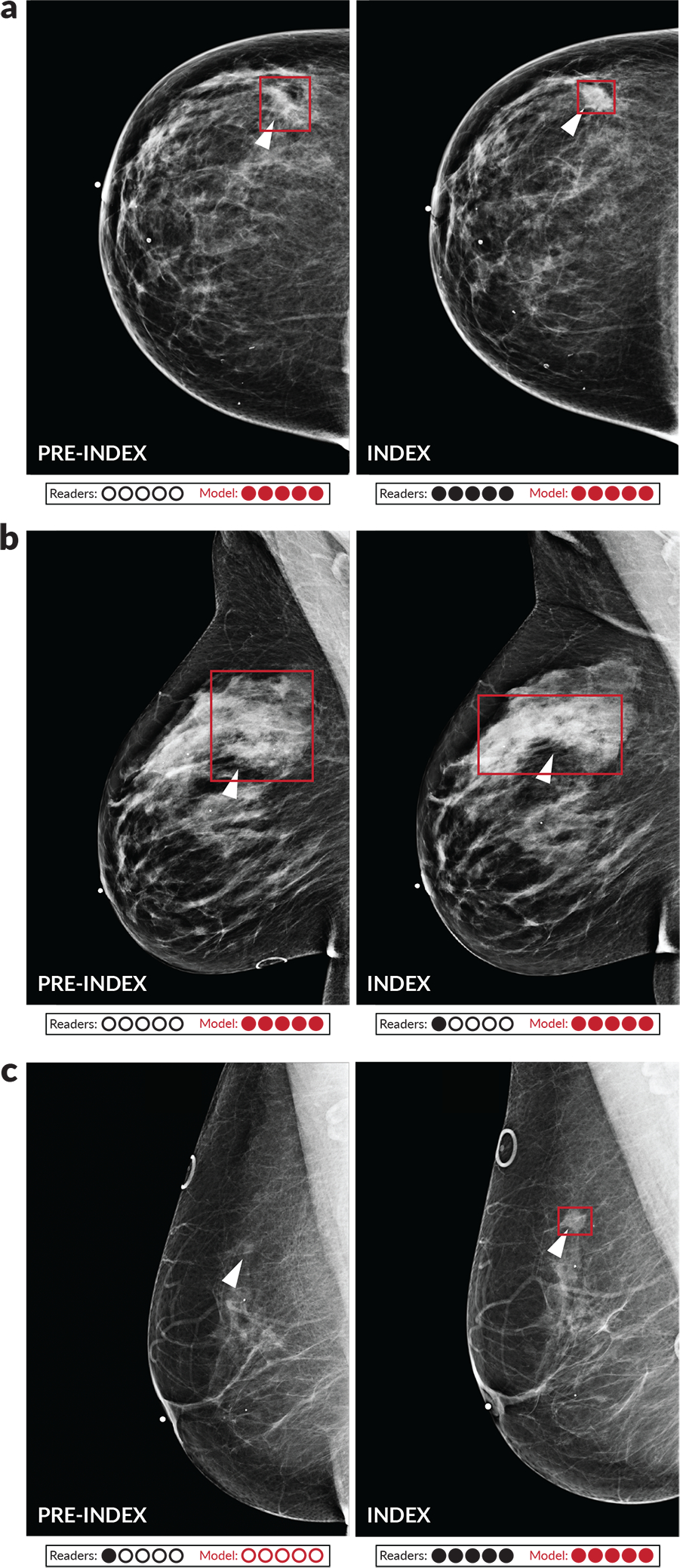

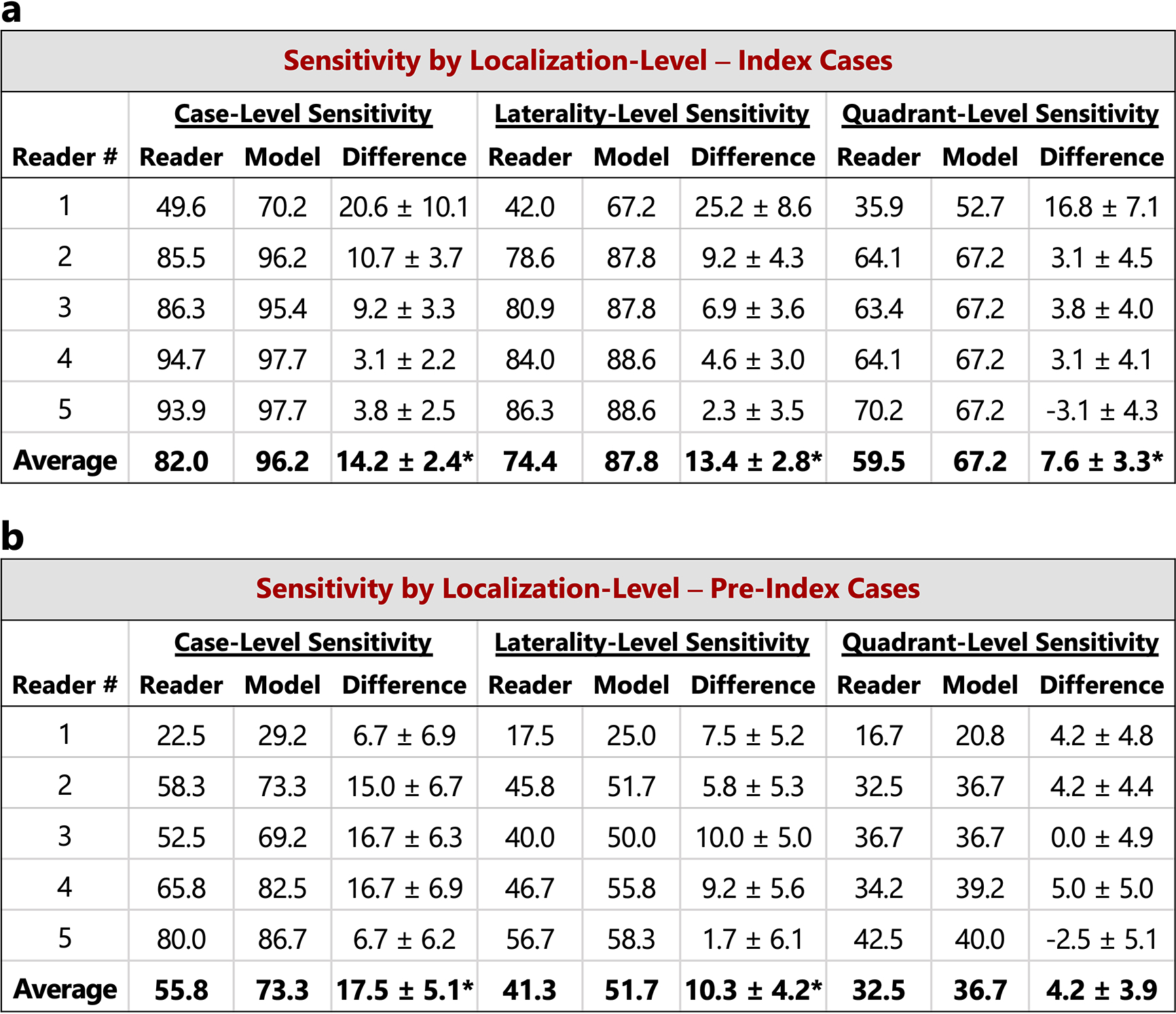

Given the interpretable localization outputs of the model, it is also possible to evaluate sensitivity while requiring correct localization. For both laterality-level and quadrant-level localization, we find that the model again demonstrated improvements in sensitivity for both the index and pre-index cases, as detailed in Extended Data Figure 5. Examples of pre-index cancer cases detected by the model are shown in Figure 3. The trend of higher model performance also holds when considering factors such as lesion type, cancer type, cancer size, and breast density (Extended Data Figure 6). Nevertheless, there are examples in which the model missed cancers that were detected by the readers, and vice versa (Extended Data Figure 7).

Figure 3: Examples of index and pre-index cancer exam pairs.

Images from three patients with biopsy-proven malignancies are displayed. For each patient, an image from the index exam from which the cancer was discovered is shown on the right, and an image from the prior screening exam acquired 12–24 months earlier and interpreted as negative is shown on the left. From top to bottom, the number of days between the index and pre-index exams is 378, 629, and 414. The dots below each image indicate reader and model performance. Specifically, the number of infilled black dots represent how many of the five readers correctly classified the corresponding case and the number of infilled red dots represent how many times the model would correctly classify the case if the model score threshold was individually set to match the specificity of each reader. The model is thus evaluated at five binary decision thresholds for comparison purposes, and we note that a different binary score threshold may be used in practice. Red boxes on the images indicate the model’s bounding box output. White arrows indicate the location of the malignant lesion. a) A cancer that was correctly classified by all readers and the deep learning model at all thresholds in the index case, but only detected by the model in the pre-index case. b) A cancer that was detected by the model in both the pre-index and index case, but only detected by one reader in the index case and zero readers in the pre-index case. c) A cancer that was detected by the readers and the model in the index case, but only detected by one reader in the pre-index case. The absence of a red bounding box indicates that the model did not detect the cancer.

Building upon the reader study performance, we evaluated standalone performance of our approach on larger, diverse datasets spanning different populations, equipment manufacturers, and modalities. These results are summarized in Table 1, which are calculated using index cancer exams. Additional results using pre-index exams and other case definitions are contained in Extended Data Figure 8, and a summary of performance across all datasets is contained in Extended Data Figure 9. Beginning with a test partition of the OMI-DB including 1,205 cancers and 1,538 confirmed negatives, our approach exhibits strong performance on DM exams from a UK screening population with an AUC of 0.963±0.003 (0.961±0.003 using all 1,967 negatives -- confirmed and unconfirmed). On a test partition of the Site A - DM dataset with 254 cancers and 7,697 confirmed negatives, the model achieved an AUC of 0.927±0.008 (0.931±0.008 using all 16,369 negatives), which is not statistically different from the results on the other tested US screening DM dataset (Site D; p=0.22). The Site A - DM dataset consists of mammograms acquired using GE equipment, as opposed to the Hologic equipment used for the majority of the other datasets.

Table 1:

Summary of additional model evaluation.

| Additional DM & DBT Evaluation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | Location | Manufacturer | Model | Input Type | AUC |

| OMI-DB | UK | Hologic | 2D | DM | 0.963 ± 0.003 |

| Site A – DM | Oregon | GE | 2D | DM | 0.927 ± 0.008 |

| Site E | China | Hologic | 2D | DM | 0.971 ± 0.005 |

| Site E (resampled) | China | Hologic | 2D | DM | 0.956 ± 0.020 |

| Site A – DBT | Oregon | Hologic | 2D* | DBT manufacturer synthetics | 0.922 ± 0.016 |

| Site A – DBT | Oregon | Hologic | 3D | DBT slices | 0.947 ± 0.012 |

| Site A – DBT | Oregon | Hologic | 2D + 3D | DBT manufacturer synthetics + slices | 0.957 ± 0.010 |

All results correspond to using the “index” exam for cancer cases and “confirmed” negatives for the non-cancer cases, except for Site E where the negatives are unconfirmed. “Pre-index” results where possible and additional analysis are included in Extended Data Figure 8. Rows 1–2: Performance of the 2D deep learning model on held-out test sets of the OMI-DB (1,205 cancers, 1,538 negatives) and Site A (254 cancers, 7,697 negatives) datasets. Rows 3–4: Performance on a dataset collected at a Chinese hospital (Site E; 533 cancers, 1,000 negatives). The dataset consists entirely of diagnostic exams given the low prevalence of screening mammography in China. Nevertheless, even when adjusting for tumor size using bootstrap resampling to approximate the distribution of tumor sizes expected in an American screening population (see Methods), the model still achieves high performance (Row 4). Rows 5–7: Performance on DBT data (Site A - DBT; 78 cancers, 518 negatives). Row 5 contains results of the 2D model fine-tuned on the manufacturer-generated synthetic 2D images, which are created to augment/substitute DM images in a DBT study (*indicates this fine-tuned model). Row 6 contains the results of the weakly-supervised 3D model, illustrating strong performance when evaluated on the MSP images computed from the DBT slices. We note that when scoring the DBT volume as the maximum bounding box score over all of the slices, the strongly-supervised 2D model used to create the MSP images exhibits an AUC of 0.865±0.020. Thus, fine-tuning this model on the MSP images significantly improves its performance. Row 7: Results when combining predictions across the final 3D model and 2D models. The standard deviation for each AUC value was calculated via bootstrapping.

To further test the generalizability of our model, we assessed performance on a DM dataset collected at an urban Chinese hospital (Site E). Testing generalization to this dataset is particularly meaningful given the low screening rates in China [28] and the known (and potentially unknown) biological differences found in mammograms between Western and Asian populations, including a greater proportion of women with dense breasts in Asian populations [37]. The deep learning model, which was evaluated locally at the Chinese hospital, generalized well to this population, achieving an AUC of 0.971±0.005 (using all negatives – “confirmation” is not possible given the lack of follow-up screening). Even when adjusting for tumor size to approximately match the statistics expected in an American screening population, the model achieved 0.956±0.020 AUC (see Table 1 and Methods).

Finally, our DBT approach performs well when evaluated at a site not used for DBT model training. Our method, which generates an optimized MSP image from the DBT slices and then classifies this image, achieved an AUC of 0.947±0.012 (with 78 cancers and 519 confirmed negatives; 0.950±0.010 using all 11,609 negative exams). If we instead simply fine-tune our strongly-supervised 2D model on the manufacturer-generated synthetic 2D images that are generated by default with each DBT study, the resulting model achieved 0.922±0.016 AUC on the test set (0.923±0.015 AUC using all negatives). Averaging predictions across the manufacturer-generated synthetic images and our MSP images results in an overall performance of 0.957±0.010 (0.959±0.008 using all negatives). Examples of the MSP images can be found in Extended Data Figure 10, which illustrate how the approach can be useful in mitigating tissue superposition compared to the manufacturer-generated synthetic 2D images.

In summary, we have developed a deep learning approach that effectively leverages both strongly and weakly-labeled data by progressively training in stages while maintaining localization-based interpretability. Our approach also extends to DBT, which is especially important given its rising use as “state-of-the-art” mammography screening and the additional time required for its interpretation. In a reader study, our system outperformed five-out-of-five full-time breast imaging specialists. This performance differential occurred on both the exams in which cancers were found in practice and the prior exams of these cancer cases. Nevertheless, prospective clinical cohort studies will ultimately provide the best comparison to the current standard of care. Furthermore, while we have aimed to test performance across various definitions of “positive” and “negative”, assigning ground truth is non-trivial for screening mammography and further real-world, regulated validation is needed before clinical use [38]. An encouraging aspect regarding generalization nonetheless, is that our reader study involved data from a site never used for model development. We additionally observe similar levels of performance in four other larger datasets, including independent data from a Chinese hospital. One particular reason why our system may generalize well is that it has also been trained on a wide array of sources, including five datasets in total. Altogether, our results show great promise towards earlier cancer detection and improved access to screening mammography using deep learning.

METHODS

Ethical Approval

All non-public datasets (data from Sites A, B, C, D, and E) were collected under Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. The following review boards were used for each dataset: Site A: Southern Oregon IRB, Site B: Rhode Island Hospital IRB, Site C: Providence IRB, Site D: Advarra IRB, and Site E: Henan Provincial People’s Hospital IRB. All of the datasets used in the study were de-identified prior to model training and testing.

Dataset Descriptions

Details of all utilized datasets are provided below. Each dataset was partitioned into one or more of the following splits: training, model selection, and/or testing. The model selection split was specifically used to choose final models and to determine when to stop model training. Data splits were created at the patient level, meaning that exams from a given patient were all in the same split. Rules for label assignment and case selection for training data varied slightly across datasets given variability in collection time periods and available metadata (as described below). However, the definitions of testing sets and label criteria were standardized across datasets unless otherwise stated. In the main text, the following definitions were used in assigning labels (as summarized in Figure 1c): Index Cancer - A mammogram obtained within the three months preceding a cancer diagnosis; Pre-Index Cancer - A mammogram interpreted as BIRADS category 1 or 2 and obtained 12–24 months prior to an index exam; Negative - A mammogram interpreted as BIRADS 1 or 2 from a patient with no known prior or future history of breast cancer; Confirmed Negative - A negative exam followed by an additional BIRADS 1 or 2 interpretation at the next screening exam 9–39 months later (which represents 1–3 years of follow-up depending on the screening paradigm with a 3 month buffer). We extend the time window beyond three years to include triennial screening (e.g., the UK). In Extended Data Figure 8, we include additional results using a 12-month time window for defining an index cancer exam, as well as including pathology-proven benign cases. Throughout, we treat “pre-index” cases as positives because, while it is not guaranteed that a pathology-proven cancer could have been determined with appropriate follow-up, it is likely that cancer existed at the time of acquisition for the vast majority of these exams [34, 35].

All datasets shared the same algorithm for creating test sets, except Site D (which is described in detail in the corresponding section below). Studies were labelled as ‘index’, ‘pre-index’, ‘confirmed negative’, ‘unconfirmed negative’, or ‘none’ based on the aforementioned criteria. For each patient in the test set, one study was chosen in the following order of descending priority: ‘index’, ‘pre-index’, ‘confirmed negative’, ‘unconfirmed negative’. If a patient had multiple exams with the chosen label, one exam was randomly sampled. If a patient had an index exam, a single pre-index exam was also included when available. For all training and testing, only craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammographic views were used. All test sets include only screening exams (i.e., screening index cancers, screening negatives, etc.) except for Site E, where all tested exams are diagnostic given the low screening rates in China. A summary of all the testing datasets and corresponding results is contained in Extended Data Figure 9. We note that the proportion of confirmed versus unconfirmed negatives varies by site largely because of differing time periods of exam acquisition (i.e., not enough time may have passed for confirmation), screening paradigms, and/or BIRADS information collection ranges. We report performance using both confirmed and unconfirmed negatives when possible to consider results on a stringent definition of negative while also evaluating on larger amounts of data.

For training, labeling amounts to assigning each training instance (e.g., an image or bounding box) a label of ‘1’ for cancer and ‘0’ for non-cancer. The chief decision for assigning images a label of ‘1’ (cancer) is in the time window allowed between cancer confirmation (biopsy) and image acquisition. For USA datasets, we set this window to 15 months. This time window was chosen to balance the risk of overfitting with still including some pre-index cancer exams for training. Localization annotations were not available for the USA datasets (except DDSM which only has index cancers), so extending the time window further could lead to overfitting on more subtle cancers. Nonetheless, the mix of yearly and bi-yearly screening in the US enables the inclusion of some pre-index cancers using a 15-month time window. For the OMI-DB from the UK, we extend this window by a year since this dataset includes a high proportion of strongly-labeled data and because the standard screening interval is longer in the UK. For non-cancers, unless otherwise noted, we use screening negative exams (BIRADS 1 or 2) from patients with no history of cancer and, when available, pathology-confirmed benign cases from patients with no history of cancer. For the pathology-confirmed benign cases, we train on both screening and diagnostic exams. For cancers, we additionally include both screening and diagnostic exams for training. We have found that training on diagnostic exams can improve performance even when evaluating only on screening exams (and vice versa). The only dataset where we train exclusively on screening exams is the Site A - DM dataset, where the lack of benign biopsy information would entail that all of the diagnostic exams to be included in training would be cancers, so we exclude diagnostics altogether to avoid such bias. As opposed to model testing where only one exam per patient is included, we use all qualified exams for a given patient for training. Below, we provide additional details of the datasets.

Digital Database of Screening Mammography (DDSM).

DDSM is a public database of scanned film mammography studies from the United States containing cases categorized as normal, benign, and malignant with verified pathology information [29]. The dataset includes radiologist-drawn segmentation maps for every detected lesion. We split the data into 90%/10% training/model selection splits, resulting in 732 cancer, 743 benign, and 807 normal studies for training. We do not use any data from DDSM for testing given that it is a scanned film dataset.

OPTIMAM Mammography Imaging Database (OMI-DB).

The OMI-DB is a publicly available dataset from the UK, containing screening and diagnostic digital mammograms primarily obtained using Hologic equipment [30]. We split the unique list of patients into 60%/20%/20% training/model selection/testing splits. This results in a training set of 5,233 cancer studies (2,332 with bounding boxes), 1,276 benign studies (296 with bounding boxes), and 16,887 negative studies. We note that although the proportion of positives to negatives in OMI-DB is much higher than the ratio expected in a screening population, the positives and negatives themselves are randomly sampled from their respective populations. Thus, given the invariance of ROC curves to incidence rates, we would not expect bias in the test set AUC in this population compared to the full population with a natural incidence rate.

Site A.

Site A is a community hospital in Oregon. The dataset from Site A primarily consists of screening mammograms, with DM data from 2010–2015 collected almost entirely from GE equipment, and DBT data from 2016–2017 collected almost entirely from Hologic equipment. For the DM data, 40% of the patients were used for training, 20% were used for model selection, and 40% were used for testing. We use the DBT data solely for testing, given its high proportion of screening exams compared to the other utilized DBT datasets. Ground truth cancer status for both modalities was obtained using a local hospital cancer registry. A radiology report also accompanied each study and contained BIRADS information. For the DBT data, a list of benigns was additionally provided by the hospital, but such information was not available for the DM data. Given the extent of longitudinal data present in the DM dataset and the lack of confirmed benign pathology information for this data, we are slightly more strict when choosing the non-cancers for training, specifically requiring the negatives to have no record of non-screening procedures or non-normal interpretations for the patient for 18 months prior to and following the exam. This results in 466 cancer studies and 48,248 negative studies for training in the Site A - DM dataset.

Site B.

Site B consists of an inpatient medical center and affiliated imaging centers in Rhode Island. The data from this site contains DBT mammograms from Hologic equipment, with a mix of screening and diagnostic exams collected retrospectively between 2016–2017. Cancer status, benign results, and BIRADS were determined using a local database. We split the list of unique patients into 80%/20% training/model selection splits. Given the relatively smaller amount of DBT available for training and the desire to test on datasets not used for training, Site B was solely used for model development. The training split consists of 13,767 negative cases, 379 benign cases, and 263 cancer cases. We note that the manufacturer-generated synthetic 2D images were also included in the weakly-supervised training for the final 2D model.

Site C.

Site C is a health system in Oregon separate from the one in Site A. From Site C, DBT cases were retrospectively collected between 2017–2018. The data consists of a mix of screening and diagnostic cases acquired almost entirely using Hologic equipment. We split the unique list of patients into 70%/30% training/model selection splits. A regional cancer registry was used to determine cancer status. Like Site B, we use Site C solely for model development. Historical BIRADS information was not readily available for all of the cases in Site C, so we use cases from patients with no entry in the regional cancer registry as non-cancers for training. Given the geographic proximity of Site C and Site A, we exclude a small number of patients that overlap in both sets when performing testing on Site A. We note that the manufacturer-generated synthetic 2D images were also included in the weakly supervised training for the final 2D model.

Site D.

Data from Site D was used for the reader study and consisted of 405 screening DM exams that were collected retrospectively from a single health system in Massachusetts with four different imaging collection centers. No data from this site was ever used for model training or selection. The exams included in the study were acquired between July 2011 and June 2014. Out of the 405 studies, 154 were negative, 131 were index cancer exams, and 120 were pre-index cancer exams. All of the negatives were confirmed negatives. The index cancer exams were screening mammograms interpreted as suspicious and confirmed to be malignant by pathology within three months of acquisition. The pre-index exams came from the same set of women as the index exams and consisted of screening exams that were interpreted as BIRADS 1 or 2 and acquired 12–24 months prior to the index exams. All studies were acquired using Hologic equipment. Case selection was conducted over several steps. First, the cancer patients included in the study were selected by taking all patients with qualifying index and pre-index exams over the specified time period using a local cancer registry. Due to PACS limitations, it was not possible to obtain some pre-index cases. Next, the non-cancer cases were chosen to have a similar distribution in patient age and breast density compared to the cancer cases using bucketing. In total, 154 non-cancer, 131 index cancer, and 120 pre-index cancer mammograms were collected from 285 women. Additional details of the case composition are contained in Extended Data Figure 6, including breast density for all cases and cancer type, cancer size, and lesion type for the cancer cases. Breast density and lesion type were obtained from the initial radiology reports. Cancer type and size were obtained from pathology reports.

Site E.

Site E consists of a dataset from an urban hospital in China collected retrospectively from a contiguous period between 2012–2017. Over this time period, all pathology-proven cancers were collected along with a uniformly random sample of non-cancers, resulting in 533 cancers, 1,000 negatives (BIRADS 1 or 2 interpretation), and 100 pathology-proven benigns. Due to the low screening rates in China, the data came from diagnostic exams (i.e., exams where the patient presented with symptoms), so the distribution of tumor sizes from the cancer cases contained more large tumors (e.g., 64% larger than 2 cm) than would be expected in a typical United States screening population. To better compare to a US screening population, results on Site E were also calculated using a bootstrap resampling method to approximately match the distribution of tumor sizes from a US population according to the American College of Radiology National Radiology Data Registry (https://nrdr.acr.org/Portal/NMD/Main/page.aspx). Using this approach, a mean AUC was computed over 5K bootstrapped populations. Site E was solely used for testing and never for model development. Furthermore, the deep learning system was evaluated locally at the hospital and data never left the site.

Model Development and Training

The first stage of model training consisted of patch-level classification [15] (Stage 1 in Figure 1). Patches of size 275×275 pixels were created from the DDSM and OMI-DB datasets after the original images were resized to a height of 1750 pixels. Data augmentation was also used when creating the patches, including random rotations of up to 360o, image resizing by up to 20%, and vertical mirroring. Preprocessing consisted of normalizing pixel values to a range of [−127.5, 127.5]. When creating patches containing lesions, a random location within the lesion boundary was selected as the center of the patch. If the resulting patch had fewer than 6 pixels containing the lesion mask, the patch was discarded and a new patch was sampled. For all patches, if the patch contained less than 10% of the breast foreground, as determined by Otsu’s method [39] for DDSM and by thresholding using the minimal pixel value in the image for OMI-DB, then the patch was discarded. In total, two million patches were created with an equal number of patches with and without lesions. For the patch classification model, we use a popular convolutional neural network, ResNet-50 [40]. The patch-based training stage itself consisted of two training sequences. First, starting from ImageNet [31] pre-trained weights, the ResNet-50 model was trained for five-way classification of lesion type: mass, calcifications, focal asymmetry, architectural distortion, or no lesion. Patches from DDSM and OMI-DB were sampled in proportion to the number of cancer cases in each dataset. The model was trained for 62,500 batches with a batch size of 16, sampling equally from all lesion types. The Adam optimizer [41] was used with a learning rate of 1e–5. Next, the patch-level model was trained for three-way classification, using labels of normal, benign, or malignant, again sampling equally from all categories. The same training parameters were also used for this stage of patch-level training.

After patch-level training, the ResNet-50 weights were used to initialize the backbone of a popular detection model, RetinaNet [42], for the second stage of training: strongly-supervised, image-level training (Stage 2 in Figure 1). Image pre-processing consisted of resizing to a height of 1750 pixels (maintaining the original aspect ratio), cropping out the background using the thresholding methods described above, and normalizing pixel values to a range of [−127.5, 127.5]. Data augmentation during training included random resizing of up to 15% and random vertical mirroring. Given the high class imbalance of mammography (far fewer positives than negatives), we implement class-balancing during training by sampling malignant and non-malignant examples with equal probability [7, 15, 16]. This class balancing was additionally implemented within datasets to prevent the model from learning biases in the different proportions of cancers across datasets. For this strongly-supervised, image-level training stage, we use the bounding boxes in the OMI-DB and DDSM datasets. Three-way bounding box classification was performed using labels of normal, benign, or malignant. The RetinaNet model was trained for 100K iterations, with a batch size of 1. The Adam optimizer [41] was used, with a learning rate of 1e–5 and gradient norm clipping with a value of 0.001. Default hyperparameters were used in the RetinaNet loss, except for a weight of 0.5 that was given to the regression loss and a weight of 1.0 that was given to the classification loss.

For the weakly-supervised training stage (Stage 3 in Figure 1), binary cancer/no-cancer classification was performed with a binary cross entropy loss. The same image input processing steps were used as in the strongly-supervised training stage. The RetinaNet architecture was converted to a classification model by taking a maximum over all of the bounding box classification scores, resulting in a model that remains fully differentiable while allowing end-to-end training with binary labels. For 2D, training consisted of 300K iterations using the Adam optimizer [41], starting with a learning rate of 2.5e–6, which was decreased by a factor of 4 every 100K iterations. Final model weights were chosen by monitoring AUC performance on the validation set every 4K iterations.

For DBT, our ‘maximum suspicion projection’ (MSP) approach is motivated by the value of DBT in providing an optimal view into a lesion that could otherwise be obscured by overlapping tissue, and by the similarity between DBT and DM images which suggests the applicability of transfer learning. Furthermore, we especially consider that the aggregate nature of 2D mammography can help reduce overfitting compared to training end-to-end on a large DBT volume. To this end, in Stage 3B the MSP images were created using the model resulting from 2D strongly-supervised training as described above, after an additional 50K training iterations with a learning rate of 2.5e–6. To create the MSP images, the 2D model was evaluated on every slice in a DBT stack except for the first and last 10% of slices (which are frequently noisy). A minimal bounding box score threshold was set at a level that achieved 99% sensitivity on the OMI-DB validation set. The bounding boxes over all evaluated slices were filtered using non-maximum suppression (NMS) using an intersection-over-union (IOU) threshold of 0.2. The image patches defined by the filtered bounding boxes were then collapsed into a single 2D image array representing an image optimized for further model training. Any “empty” pixels in the projection were infilled with the corresponding pixels from the center slice of the DBT stack, resulting in the final MSP images. Overall, the MSP process is akin to a maximum intensity projection (MIP) except that the maximum is computed over ROI malignancy suspicion predicted by an AI model instead of over pixel-level intensity. Training on the resulting MSP images was conducted similar to the 2D weakly-supervised approach, except that the model was trained for 100K iterations. The input processing parameters used for 2D images were reused for DBT slices and MSP images.

After weakly-supervised training for both the 2D and 3D models, we fine-tune the regression (i.e., localization) head of the RetinaNet architecture on the strongly-labeled data used in Stage 2. Specifically, the backbone and classification head of the network are frozen and only the regression head is updated during this fine-tuning. This allows the regression head to adapt to any change in the weights in the backbone of the network during the weakly-supervised training stage, where the regression head is not updated. For this regression fine-tuning stage, the network is trained for 50K iterations with a learning rate of 2.5e–6 using the same preprocessing and data augmentation procedures as the previous stages.

Final model selection was based on performance on the held-out model selection data partition. The final model was an aggregation of three equivalently-trained models starting from different random seeds. A prediction score for a given image was calculated by averaging across the three models’ predictions for both horizontal orientations of the image (i.e., an average over six scores). Regression coordinates of the bounding box anchors were additionally averaged across the three models. Each breast was assigned a malignancy score by taking the average score of all of its views. Each study was assigned a score by taking the greater of its two breast-level scores. Finally, while we note that random data augmentation was used during model training as described above, data processing during testing is deterministic, as are the models themselves.

The deep learning models were developed and evaluated using the Keras (https://keras.io/) and keras-retinanet (https://github.com/fizyr/keras-retinanet) libraries with a Tensorflow backend (https://www.tensorflow.org). Data analysis was performed using the Python language with the numpy, pandas, scipy, and sklearn packages. DCMTK (https://dicom.offis.de/dcmtk.php.en) and Pydicom (https://pydicom.github.io/) were used for processing DICOM files.

Reader Study

The reader study was performed to directly assess the performance of the proposed deep learning system in comparison to expert radiologists. While a reader study is certainly an artificial setting, such studies avoid the “gatekeeper bias” inherent in retrospective performance comparison [17], since the ground truth of each case is established a priori in reader studies. Recent evidence also suggests that the rate of positive enrichment itself in reader studies may have little effect on reader aggregate ROC performance [43, 44].

Reader Selection.

Five board-certified and MQSA-qualified radiologists were recruited as readers for the reader study. All readers were fellowship-trained in breast imaging and had practiced for an average of 5.6 years post-fellowship (range 2–12 years). The readers read an average of 6,969 mammograms over the year preceding the reader study (range of 2,921 – 9,260), 60% of which were DM and 40% of which were DBT.

Study Design.

The data for the reader study came from Site D as described above. The study was conducted in two sessions. During the first session, radiologists read the 131 index cancer exams and 76 of the negative exams. During the second session, radiologists read the 120 pre-index exams and the remaining 78 negative exams. There was a washout period of at least 4 weeks in between the two sessions for each reader. The readers were instructed to give a forced BIRADS score for each case (1 – 5). BIRADS 1 and 2 were considered no recall, and BIRADS 3, 4, and 5 were considered recall [36]. Radiologists did not have any information about the patients (such as previous medical history, radiology reports, and other patient records), and were informed that the study dataset is enriched with cancer mammograms relative to the standard prevalence observed in screening; however, they were not informed about the proportion of case types. All readers viewed and interpreted the studies on dedicated mammography workstations in an environment similar to their clinical practice. Readers recorded their interpretations in electronic case report forms using SurveyMonkey (San Mateo, CA). In addition to a forced BIRADS, readers provided breast density classification and, for each detected lesion, the lesion type, laterality, quadrant, and a 0–100 probability of malignancy score (for up to four lesions). In the main text, reader binary recall decisions using BIRADS are used for analysis because this more closely reflects clinical practice. In Extended Data Figure 1, reader ROC curves using the probability of malignancy score are also computed, which show similar results.

Localization-Based Analysis.

While the reader study results in the main text correspond to case-level classification performance, localization-based analysis was also performed. In the study, readers reported the breast laterality and quadrant for each lesion that was determined to warrant recall. Ground truth laterality and quadrant for malignant lesions was provided by the clinical lead of the reader study by inspecting the mammogram images along with pathology and radiology reports. For the pre-index cases, the ground truth location was set to the ground truth location of the corresponding index case, even if the lesion was deemed not visible in the pre-index exam. The proposed deep learning model provides localization in the form of bounding boxes. To compare to the readers and to also act as an exercise in model output interpretability, a MQSA-qualified radiologist from a different practice than the reader study site mapped the outputted boxes of the model to breast laterality and quadrant. This radiologist was blinded to the ground truth of the cases and was instructed to estimate the location of the centroid for each given bounding box, restricting the estimation to one quadrant.

Localization-based results are contained in Extended Data Figure 5. Both laterality-based and quadrant-based localization sensitivities are considered, requiring correct localization at the corresponding level in addition to recalling the case. Since the readers reported at most one lesion for the vast majority of cases (90%) and to avoid scenarios where predictions involving many locations are rewarded, our primary analysis restricts the predicted locations to the location corresponding to the highest scoring lesion. For the model, this corresponds to taking the highest scoring bounding box in the highest scoring laterality. For the readers, the probability of malignancy score provided for each lesion was used to select the highest scoring location. In cases with more than one malignant lesion, a true positive was assigned if the reader or model location matched the location of any of the malignant lesions. As in Fig 2a.ii and Fig. 2b.ii, we compare the sensitivity of each reader to the model by choosing a model score threshold that matches the specificity of the given reader. The model is also compared to the reader average in a similar fashion. We additionally report results where we consider a prediction a true positive if any reported lesion by the reader matches the ground truth location (i.e., instead of just the top scoring lesion), while still restricting the model to one box per study.

Statistical Analysis

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used throughout the text as a main evaluation method. We note that ROC analysis is the standard method for assessing diagnostic performance because it is invariant to the ratio of positive to negative cases, and because it allows for comparing performance across the entire range of possible recall rates (i.e., operating points). Confidence intervals and standard deviations for AUCs and average readers’ sensitivity and specificity were computed via bootstrapping with 10,000 random resamples. The p-values for comparing the model’s sensitivity and specificity with the average reader sensitivity and specificity were computed by taking the proportion of times the difference between the model and readers was less than 0 across the bootstrap resamples. The p-value for comparing AUCs between two models on the same dataset was computed using the DeLong method [45]. Bootstrapping with 10,000 random resamples was used to compare AUC performance across datasets.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Life Sciences Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data Availability

Applications for access of the OPTIMAM Mammography Imaging Database (OMI-DB) can be completed at https://medphys.royalsurrey.nhs.uk/omidb/getting-access/. The Digital Database for Screening Mammography (DDSM) can be accessed at http://www.eng.usf.edu/cvprg/Mammography/Database.html. The remainder of the datasets used are not currently permitted for public release by their respective Institutional Review Boards.

Code Availability

Code to enable model evaluation for research purposes via an evaluation server is made available at https://github.com/DeepHealthAI/nature_medicine_2020.

Extended Data

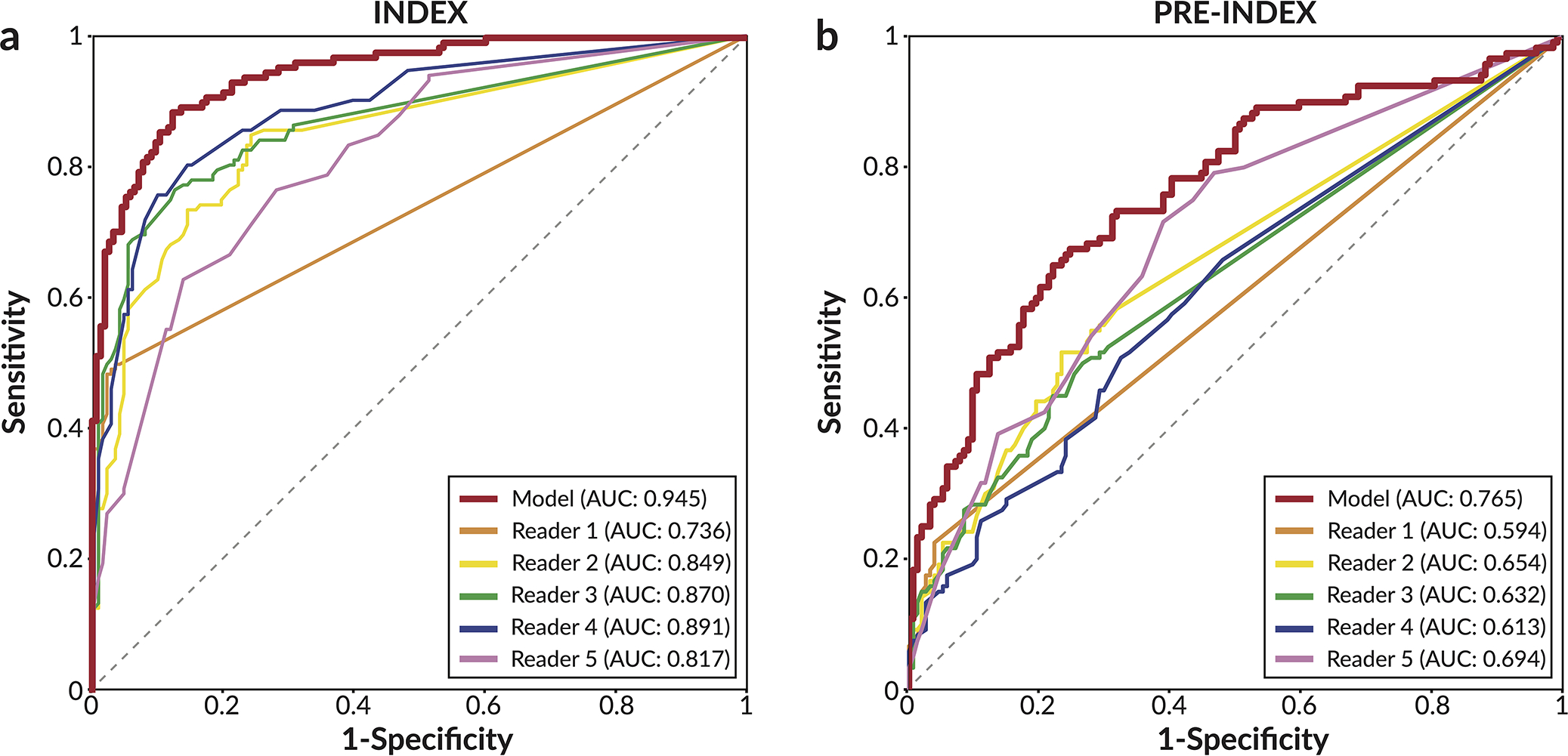

Extended Data Figure 1: Reader ROC curves using Probability of Malignancy metric.

For each lesion deemed suspicious enough to warrant recall, readers assigned a 0–100 probability of malignancy (POM) score. Cases not recalled were assigned a score of 0. a) ROC curve using POM on the 131 index cancer cases and 154 confirmed negatives. In order of reader number, the reader AUCs are 0.736±0.023, 0.849±0.022, 0.870±0.021, 0.891±0.019, and 0.817±0.025. b) ROC curve using POM on the 120 pre-index cancer cases and 154 confirmed negatives. In order of reader number, the reader AUCs are 0.594±0.021, 0.654±0.031, 0.632±0.030, 0.613±0.033, and 0.694±0.031. The standard deviation for each AUC value was calculated via bootstrapping.

Extended Data Figure 2: Results of model compared to synthesized panel of readers.

Comparison of model ROC curves to every combination of 2, 3, 4, and 5 readers. Readers were combined by averaging BIRADS scores, with sensitivity and specificity calculated using a threshold of 3. On both the (a) index cancer exams and (b) pre-index cancer exams, the model outperformed every combination of readers, as indicated by each combination falling below the model’s respective ROC curve. The reader study dataset consists of 131 index cancer exams, 120 pre-index cancer exams, and 154 confirmed negatives.

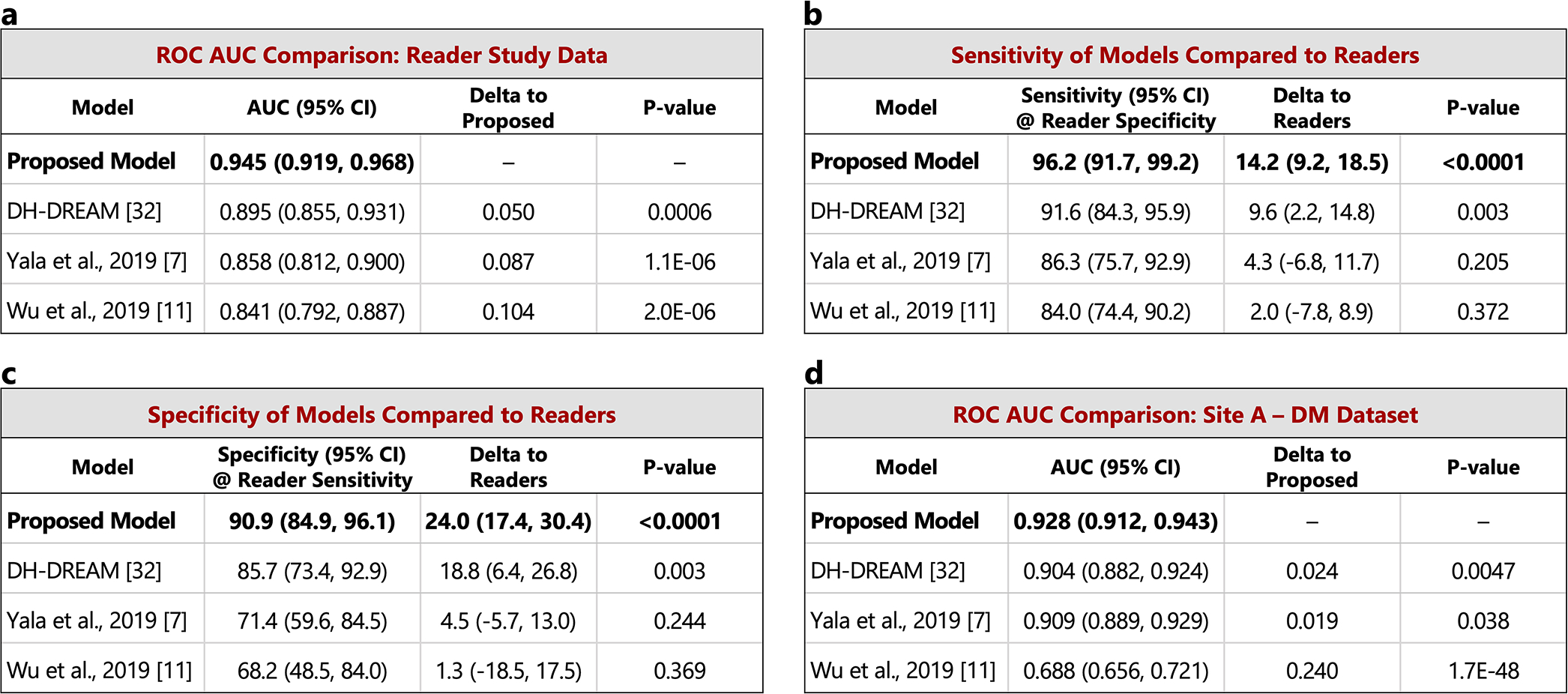

Extended Data Figure 3: Comparison to recent work – index cancer exams.

The performance of the proposed model is compared to other recently published models on the set of index cancer exams and confirmed negatives from our reader study (a-c) and the “Site A - DM dataset” (d). P-values for AUC differences were calculated using the DeLong method [45] (two sided). Confidence intervals for AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were computed via bootstrapping. a) ROC AUC comparison: Reader study data (Site D). The Site D dataset contains 131 index cancer exams and 154 confirmed negatives. The DeLong method z-values corresponding to the AUC differences are, from top to bottom, 3.44, 4.87, and 4.76. b) Sensitivity of models compared to readers. Sensitivity was obtained at the point on the ROC curve corresponding to the average reader specificity. Delta values show the difference between model sensitivity and average reader sensitivity and the p-values correspond to this difference (computed via bootstrapping). c) Specificity of models compared to readers. Specificity was obtained at the point on the ROC curve corresponding to the average reader sensitivity. Delta values show the difference between model specificity and average reader specificity and the p-values correspond to this difference (computed via bootstrapping). d) ROC AUC comparison: Site A - DM dataset. Compared to the original dataset, 60 negatives (0.78% of the negatives) were excluded from the comparison analysis because at least one of the models were unable to successfully process these studies. All positives were successfully processed by all models, resulting in 254 index cancer exams and 7,637 confirmed negatives for comparison. The DeLong method z-values corresponding to the AUC differences are, from top to bottom, 2.83, 2.08, and 14.6.

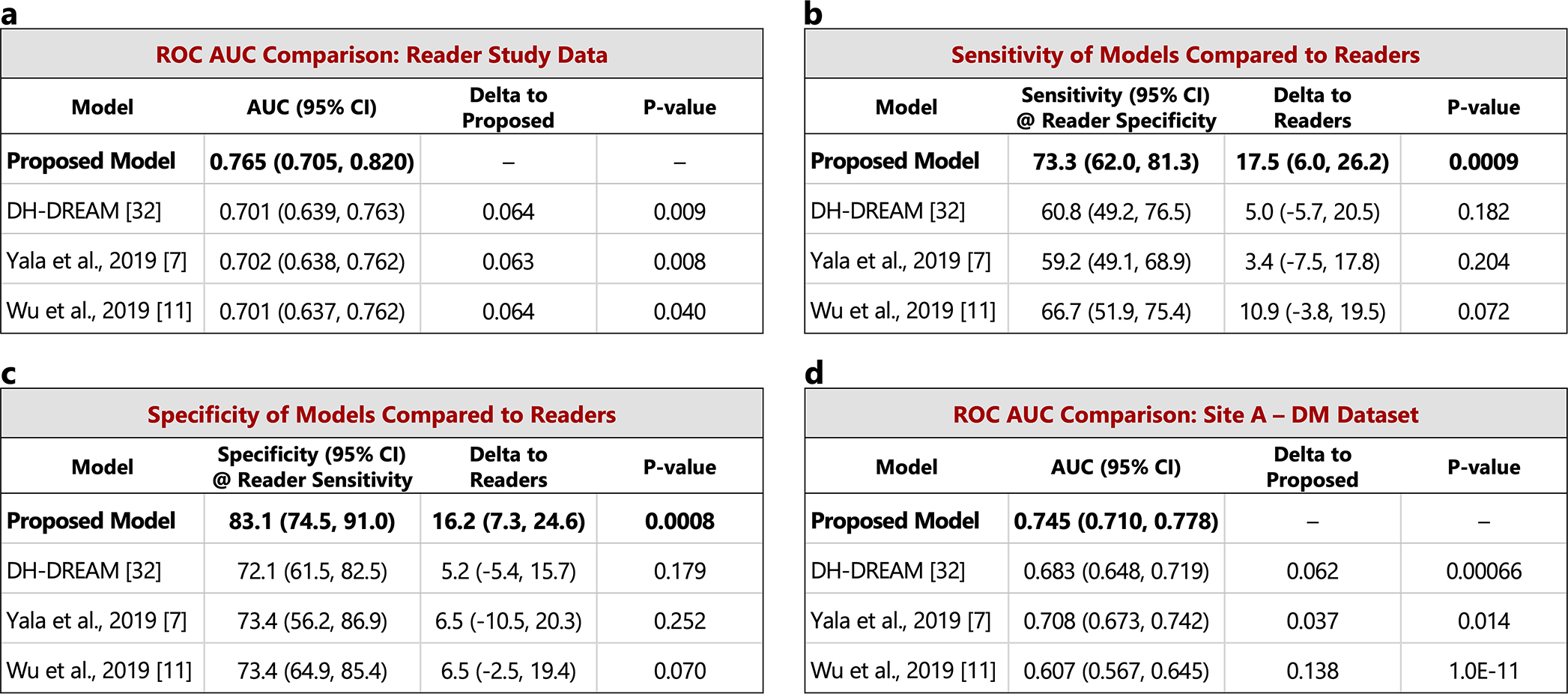

Extended Data Figure 4: Comparison to recent work – pre-index cancer exams.

The performance of the proposed model is compared to other recently published models on the set of pre-index cancer exams and confirmed negatives from our reader study (a-c) and the “Site A - DM dataset” (d). P-values for AUC differences were calculated using the DeLong method [45] (two sided). Confidence intervals for AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were computed via bootstrapping. a) ROC AUC comparison: Reader study data (Site D). The Site D dataset contains 120 pre-index cancer exams and 154 confirmed negatives. The DeLong method z-values corresponding to the AUC differences are, from top to bottom, 2.60, 2.66, and 2.06. b) Sensitivity of models compared to readers. Sensitivity was obtained at the point on the ROC curve corresponding to the average reader specificity. Delta values show the difference between model sensitivity and average reader sensitivity and the p-values correspond to this difference (computed via bootstrapping). c) Specificity of models compared to readers. Specificity was obtained at the point on the ROC curve corresponding to the average reader sensitivity. Delta values show the difference between model specificity and average reader specificity and the p-values correspond to this difference (computed via bootstrapping). d) ROC AUC comparison: Site A - DM dataset. Compared to the original dataset, 60 negatives (0.78% of the negatives) were excluded from the comparison analysis because at least one of the models were unable to successfully process these studies. All positives were successfully processed by all models, resulting in 217 pre-index cancer exams and 7,637 confirmed negatives for comparison. The DeLong method z-values corresponding to the AUC differences are, from top to bottom, 3.41, 2.47, and 6.81.

Extended Data Figure 5: Localization-based sensitivity analysis.

In the main text, case-level results are reported. Here, we additionally consider lesion localization when computing sensitivity for the reader study. Localization-based sensitivity is computed at two levels - laterality and quadrant (see Methods). As in Figure 2 in the main text, we report the model’s sensitivity at each reader’s specificity (96.1, 68.2, 69.5, 51.9, and 48.7 for Readers 1–5 respectively) and at the reader average specificity (66.9). a) Localization-based sensitivity for the index cases (131 cases). b) Localization-based sensitivity for the pre-index cases (120 cases). For reference, the case-level sensitivities are also provided. We find that the model outperforms the reader average for both localization levels and for both index and pre-index cases (*p<0.05; Specific p-values: index- laterality: p<1e–4, index - quadrant: p=0.01, pre-index - laterality: p=0.01, pre-index - quadrant: p=0.14). The results in the tables below correspond to restricting localization to the top scoring predicted lesion for both reader and model (see Methods). If we allow localization by any predicted lesion for readers while still restricting the model to only one predicted bounding box, the difference between the model and reader average performance is as follows (positive values indicate higher performance by model): index - laterality: 11.2±2.8 (p=0.0001), index - quadrant: 4.7±3.3 (p=0.08), pre-index - laterality: 7.8±4.2 (p=0.04), pre-index - quadrant: 2.3±3.9 (p=0.28). P-values and standard deviations were computed via bootstrapping. Finally, we note that while the localization-based sensitivities of the model may seem relatively low on the pre-index cases, the model is evaluated in a strict scenario of only allowing one box per study and crucially, all of the pre-index effectively represent “misses” in the clinic. Even when set to a specificity of 90% [36], the model still detects a meaningful number of the missed cancers while requiring localization, with a sensitivity of 37% and 28% for laterality and quadrant localization, respectively.

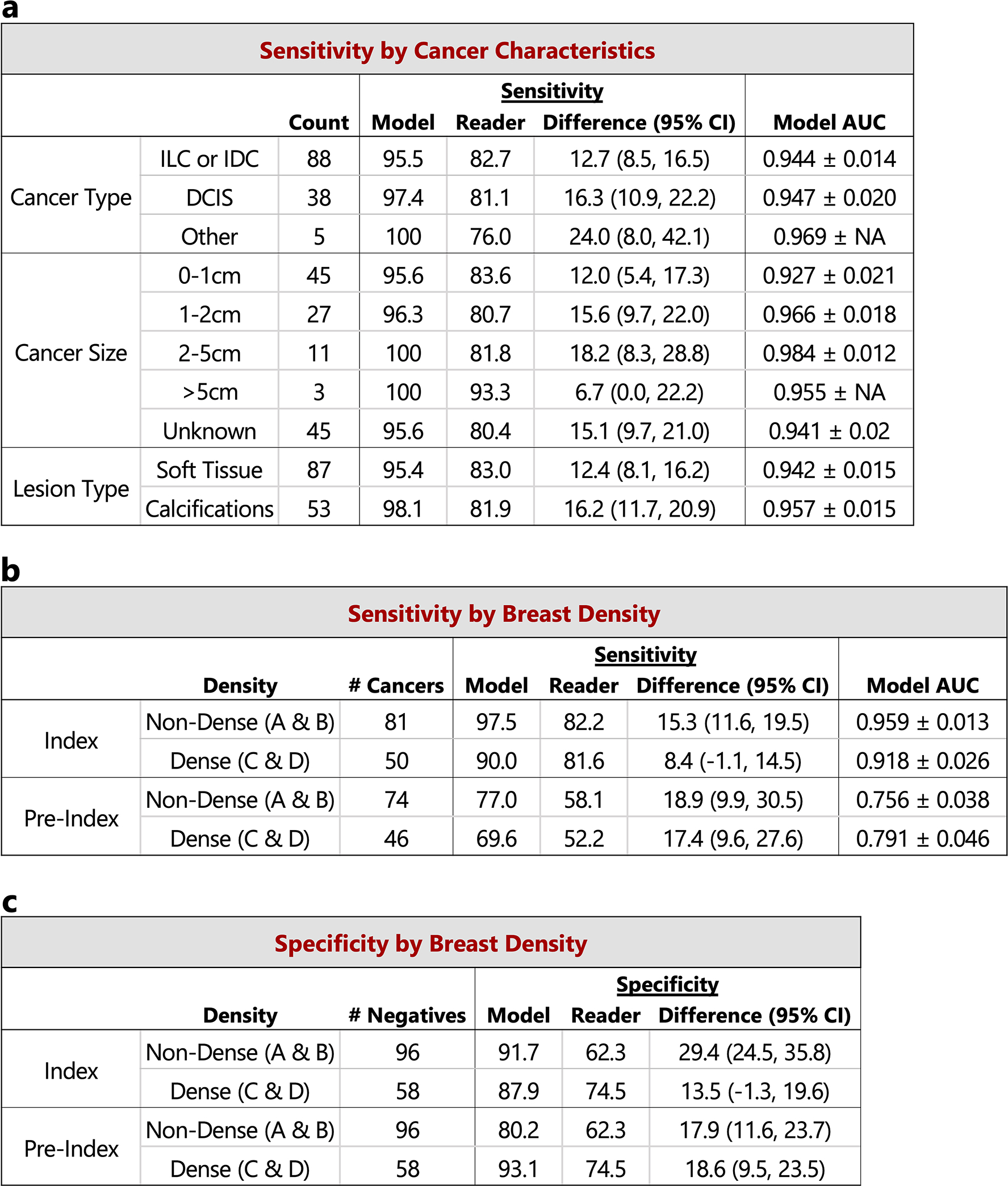

Extended Data Figure 6: Reader study case characteristics and performance breakdown.

The performance of the proposed deep learning model compared to the reader average grouped by various case characteristics is shown. For sensitivity calculations, the score threshold for the model is chosen to match the reader average specificity. For specificity calculations, the score threshold for the model is chosen to match the reader average sensitivity. a) Sensitivity and model AUC grouped by cancer characteristics, including cancer type, cancer size, and lesion type. The cases correspond to the index exams since the status of these features are unknown at the time of the pre-index exams. Lesion types are grouped by soft tissue lesions (masses, asymmetries, and architectural distortions) and calcifications. Malignancies containing lesions of both types are included in both categories (9 total cases). ‘NA’ entries for model AUC standard deviation indicate that there were too few positive samples for bootstrap estimates. The 154 confirmed negatives in the reader study dataset were used for each AUC calculation. b) Sensitivity and model AUC by breast density. The breast density is obtained from the original radiology report for each case. c) Specificity by breast density. Confidence intervals and standard deviations were computed via bootstrapping.

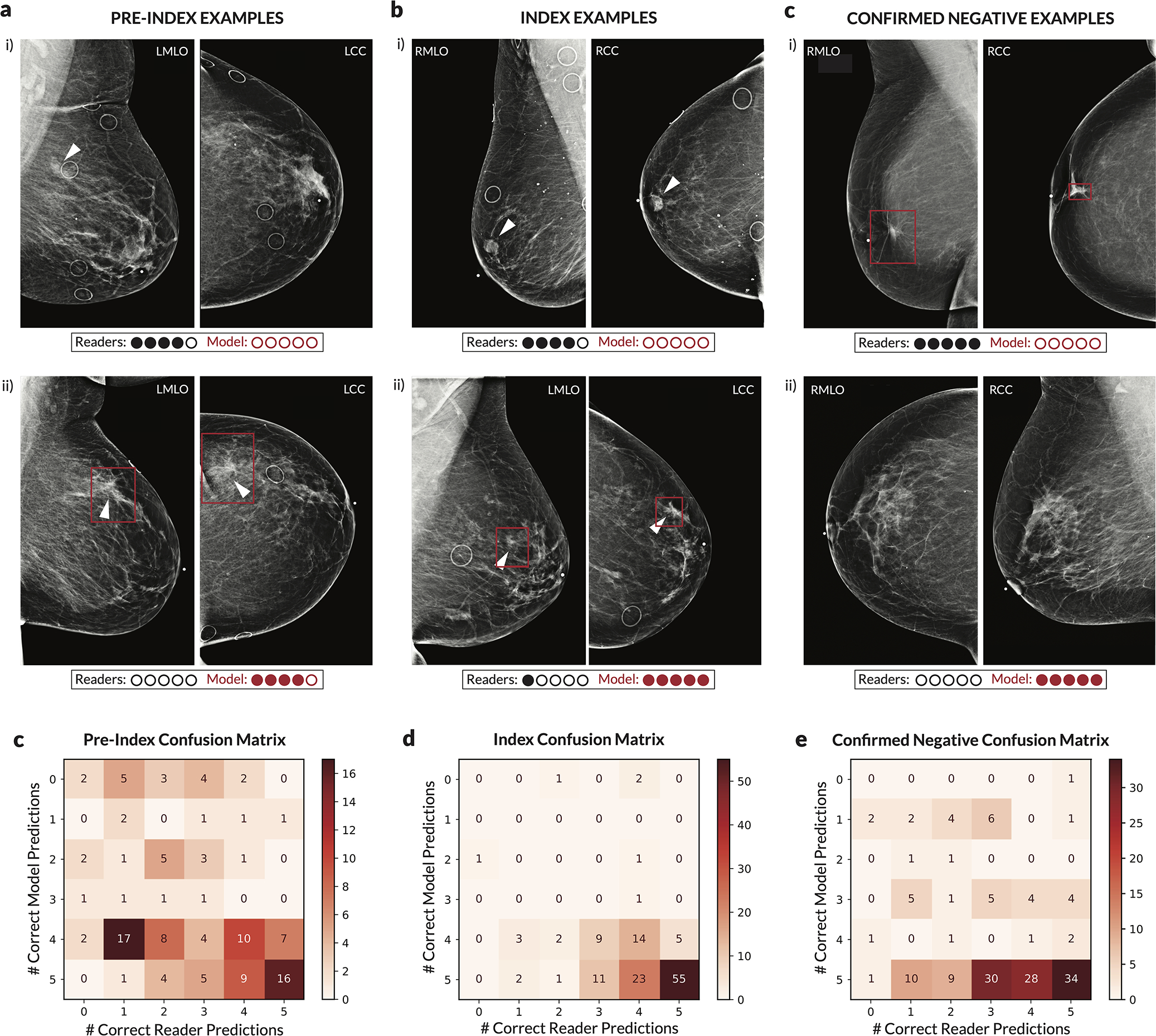

Extended Data Figure 7: Discrepancies between readers and deep learning model.

For each case, the number of readers that correctly classified the case was calculated along with the number of times the deep learning model would classify the case correctly when setting a score threshold to correspond to either the specificity of each reader (for index and pre-index cases) or the sensitivity of each reader (for confirmed negative cases). Thus, for each case, 0–5 readers could be correct, and the model could achieve 0–5 correct predictions. The evaluation of the model at each of the operating points dictated by each reader was done to ensure a fair, controlled comparison (i.e., when analyzing sensitivity, specificity is controlled). We note that in practice a different operating point (i.e., score threshold) may be used. The examples shown illustrate discrepancies between model and human performance, with the row of dots below each case illustrating the number of correct predictions. Red boxes on the images indicate the model’s bounding box output. White arrows indicate the location of a malignant lesion. a) Examples of pre-index cases where the readers outperformed the model (i) and where the model outperformed the readers (ii). b) Examples of index cases where the readers outperformed the model (i) and where the model outperformed the readers (ii). c) Examples of confirmed negative cases where the readers outperformed the model (i) and where the model outperformed the readers (ii). For the example in c.i.), the patient previously had surgery six years ago for breast cancer at the location indicated by the model, but the displayed exam and the subsequent exam the following year were interpreted as BIRADS 2. For the example in c.ii.), there are posterior calcifications that had previously been biopsied with benign results, and all subsequent exams (including the one displayed) were interpreted as BIRADS 2. d) Full confusion matrix between the model and readers for pre-index cases. e) Full confusion matrix between the model and readers for index cases. f) Full confusion matrix between the model and readers for confirmed negative cases.

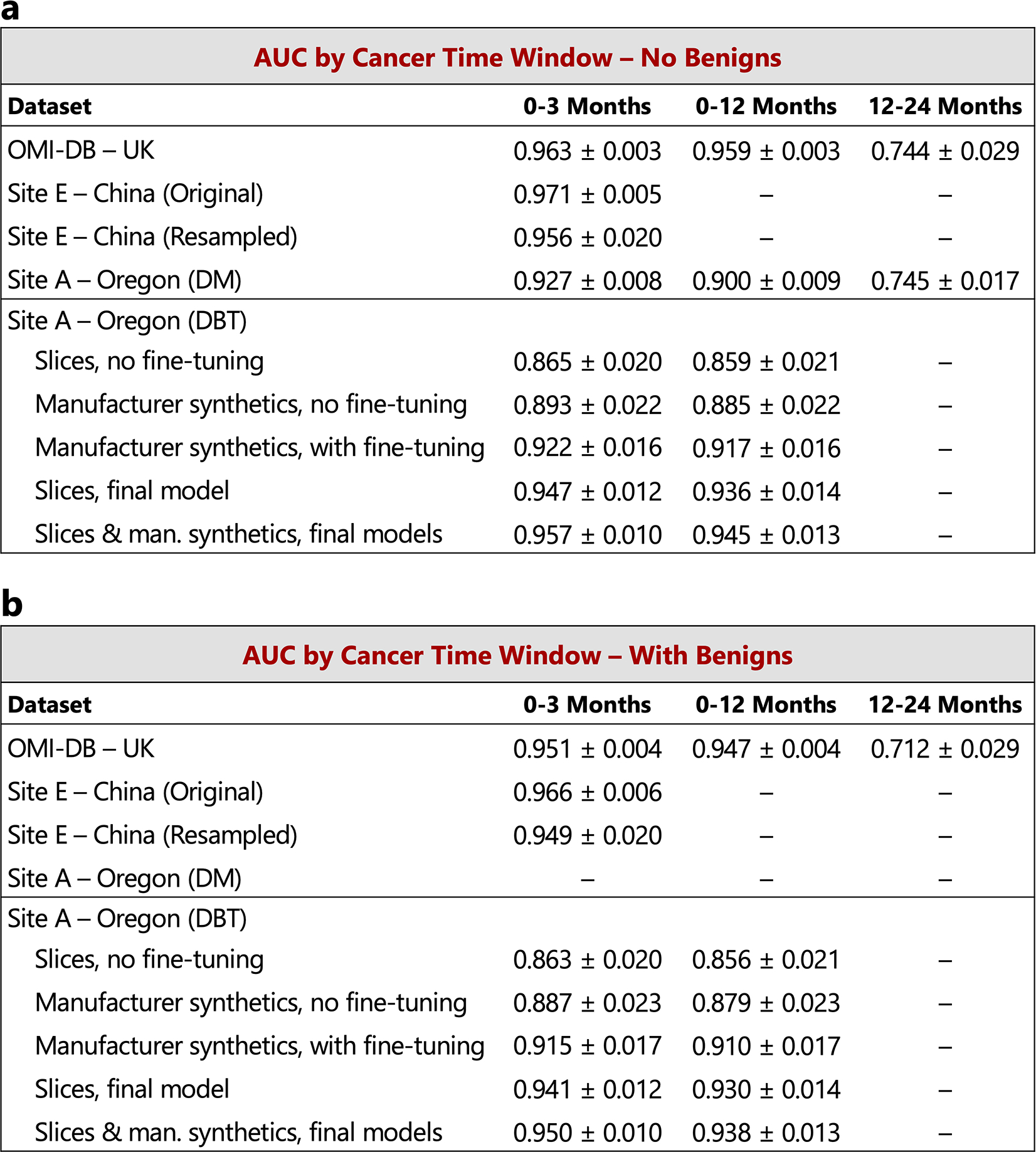

Extended Data Figure 8: Performance of proposed models under different case compositions.

Unless otherwise noted, in the main text we chose case compositions and definitions to match those of the reader study, specifically index cancer exams were mammograms acquired within 3 months preceding a cancer diagnosis and non-cancers were negative mammograms (BIRADS 1 or 2) that were “confirmed” by a subsequent negative screen. Here, we additionally consider (a) a 12-month definition of index cancers, i.e., mammograms acquired within 0–12 months preceding a cancer diagnosis, as well as (b) including biopsy-proven benign cases as non-cancers. The 3-month time window for cancer diagnosis includes 1,205, 533, 254, and 78 cancer cases for OMI-DB, Site E, Site A - DM, and Site A - DBT, respectively. The number of additional cancer cases included in the 12-month time window is 38, 46, and 7 for OMI-DB, Site A - DM, and Site A - DBT, respectively. A 12–24 month time window results in 68 cancer cases for OMI-DB and 217 cancer cases for Site A - DM. When including benign cases, those in which the patient was recalled and ultimately biopsied with benign results, we use a 10:1 negative to benign ratio to correspond with a typical recall rate in the United States [36]. For a given dataset, the negative cases are shared amongst all cancer time window calculations, with 1,538, 1,000, 7,697, and 518 negative cases for OMI-DB, Site E, Site A - DM, and Site A - DBT, respectively. For all datasets except Site E, the calculations below involve confirmed negatives. Dashes indicate calculations that are not possible given the data and information available for each site. The standard deviation for each AUC value was calculated via bootstrapping.

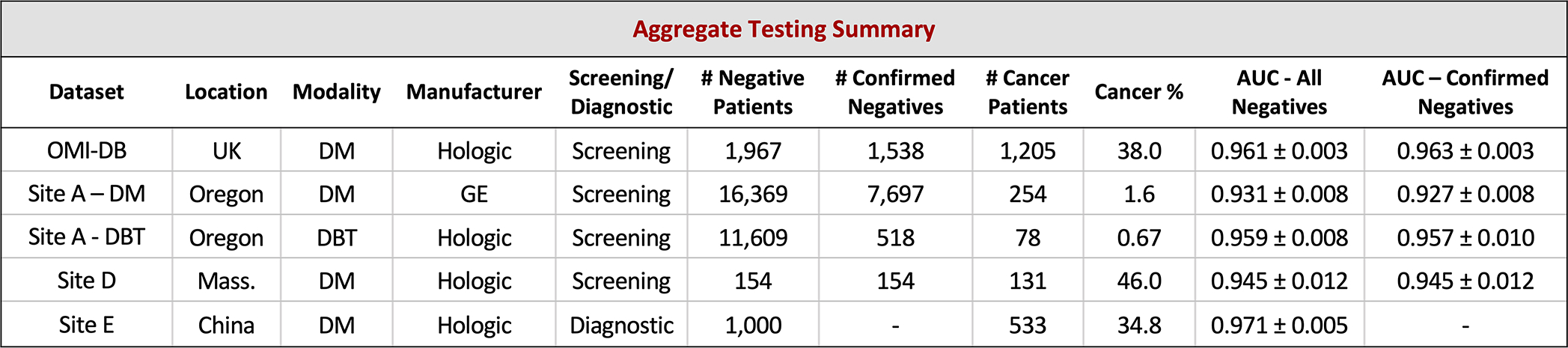

Extended Data Figure 9: Aggregate summary of testing data and results.

Results are calculated using index cancer exams and both confirmed negatives and all negatives (confirmed and unconfirmed) separately. While requiring negative confirmation excludes some data, similar levels of performance are observed across both confirmation statuses in each dataset. Across datasets, performance is also relatively consistent, though there is some variation as might be expected given different screening paradigms and population characteristics. Further understanding of performance characteristics across these populations and other large-scale cohorts will be important future work. The standard deviation for each AUC value was calculated via bootstrapping.

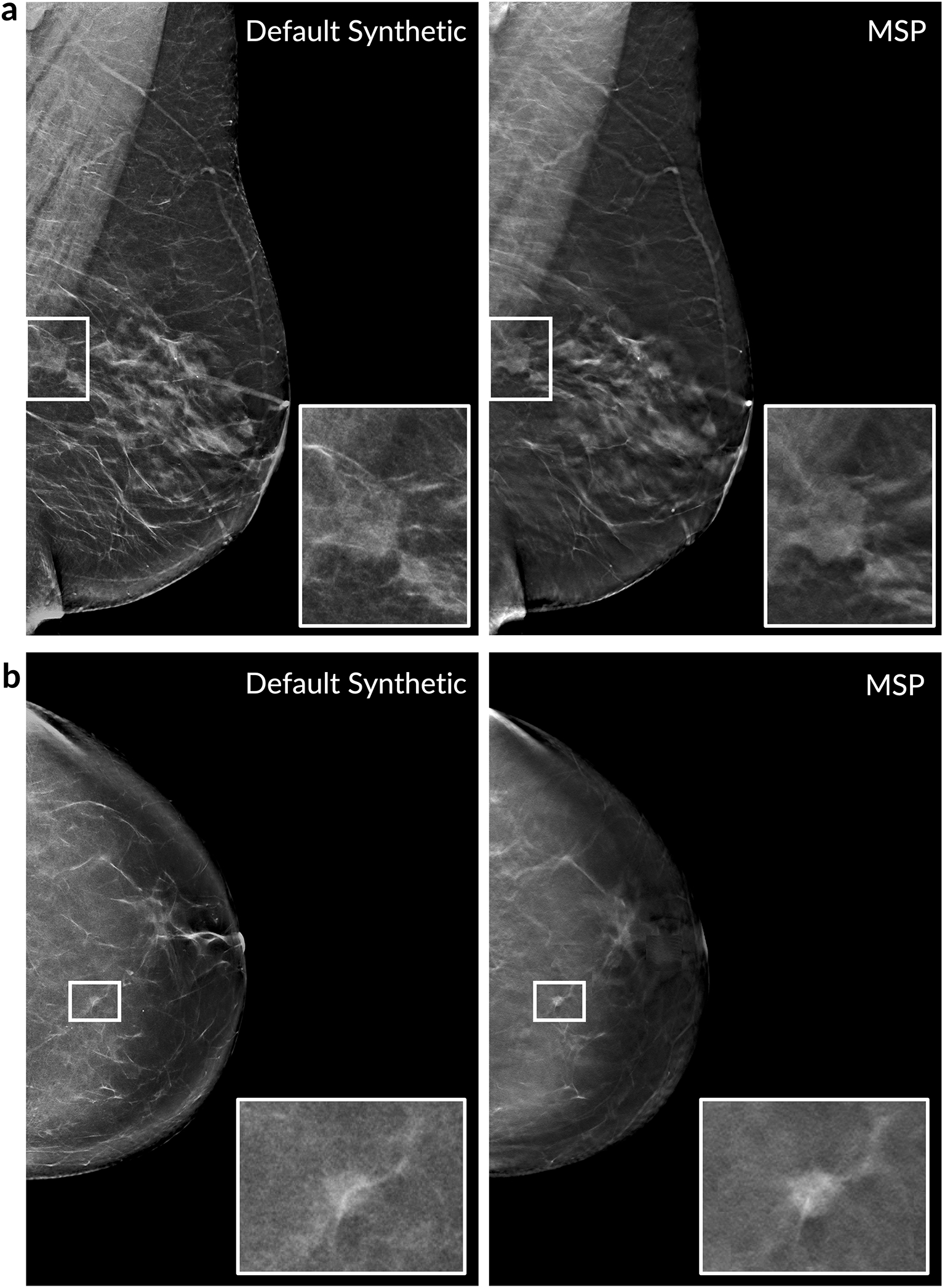

Extended Data Figure 10: Examples of maximum suspicion projection (MSP) images.

Two cancer cases are presented. Left column: Default 2D synthetic images. Right column: MSP images. The insets highlight the malignant lesion. In both cases, the deep learning algorithm scored the MSP image higher for the likelihood of cancer (a: 0.77 vs. 0.14, b: 0.87 vs. 0.31). We note that the deep learning algorithm correctly localized the lesion in both of the MSP images as well.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to S. Venkataraman, E. Ghosh, A. Newburg, M. Tyminski, and N. Amornsiripanitch for participation in the study. We also thank C. Lee, D. Kopans, P. Golland, and J. Holt for guidance and valuable discussions. We additionally thank T. Witzel, I. Swofford, M. Tomlinson, J. Roubil, J. Watkins, Y. Wu, H. Tan, and S. Vedantham for assistance in data acquisition and processing. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (1R37CA240403-01A1 & 1R44CA240022) and the National Science Foundation (SBIR 1938387) received by DeepHealth Inc. All of the non-public datasets used in the study were collected retrospectively and de-identified under IRB-approved protocols in which informed consent was waived.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

W.L., A.R.D., B.H., J.G.K., G.G., J.O.O., Y.B., and A.G.S. are employees of RadNet Inc., the parent company of DeepHealth Inc. M.B. serves as a consultant for DeepHealth Inc. Two patent disclosures have been filed related to the study methods under inventor W.L.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, and Jemal A Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 68(6), 394–424 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, Fryback DG, Clarke L, Zelen M, Mandelblatt JS, Yakovlev AY, Habbema JDF, and Feuer EJ Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 353(17), 1784–1792 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Seely JM and Alhassan T Screening for breast cancer in 2018 - what should we be doing today?. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.) 25(Suppl 1), S115–S124 6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Majid AS, Shaw De Paredes E, Doherty RD, Sharma NR, and Salvador X Missed breast carcinoma: pitfalls and pearls. RadioGraphics 23, 881–895 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rosenberg RD, Yankaskas BC, Abraham LA, Sickles EA, Lehman CD, Geller BM, Carney PA, Kerlikowske K, Buist DS, Weaver DL, Barlow WE, and Ballard-Barbash R Performance benchmarks for screening mammography. Radiology 241(1), 55–66 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yala A, Lehman C, Schuster T, Portnoi T, and Barzilay R A deep learning mammography-based model for improved breast cancer risk prediction. Radiology (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yala A, Schuster T, Miles R, Barzilay R, and Lehman C A deep learning model to triage screening mammograms: a simulation study. Radiology (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Conant EF, Toledano AY, Periaswamy S, Fotin SV, Go J, Boatsman JE, and Hoffmeister JW Improving accuracy and efficiency with concurrent use of artificial intelligence for digital breast tomosynthesis. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rodriguez-Ruiz A, Lång K, Gubern-Merida A, Broeders M, Gennaro G, Clauser P, Helbich TH, Chevalier M, Tan T, Mertelmeier T, Wallis MG, Andersson I, Zackrisson S, Mann RM, and Sechopoulos I Stand-alone artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection in mammography: comparison with 101 radiologists. Journal of the National Cancer Institute (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rodríguez-Ruiz A, Krupinski E, Mordang JJ, Schilling K, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Sechopoulos I, and Mann RM Detection of breast cancer with mammography: effect of an artificial intelligence support system. Radiology (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wu N, Phang J, Park J, Shen Y, Huang Z, Zorin M, Jastrzebski S, Fevry T, Katsnelson J, Kim E, Wolfson S, Parikh U, Gaddam S, Lin LLY, Ho K, Weinstein JD, Reig B, Gao Y, Pysarenko HTK, Lewin A, Lee J, Airola K, Mema E, Chung S, Hwang E, Samreen N, Kim SG, Heacock L, Moy L, Cho K, and Geras KJ Deep neural networks improve radiologists’ performance in breast cancer screening. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 10 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ribli D, Horváth A, Unger Z, Pollner P, and Csabai I Detecting and classifying lesions in mammograms with deep learning. Scientific Reports 8(1), 4165 3 (2018). 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kooi T, Litjens G, van Ginneken B, Gubern-Mérida A, Sánchez CI, Mann R, den Heeten A, and Karssemeijer N Large scale deep learning for computer aided detection of mammographic lesions. Medical Image Analysis 35, 303–312 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Geras KJ, Wolfson S, Shen Y, Wu N, Kim SG, Kim E, Heacock L, Parikh U, Moy L, and Cho K High-resolution breast cancer screening with multi-view deep convolutional neural networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.07047 (2017).

- [15].Lotter W, Sorensen G, and Cox D A multi-scale CNN and curriculum learning strategy for mammogram classification. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, (2017). [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schaffter T, Buist DSM, Lee CI, Nikulin Y, Ribli D, Guan Y, Lotter W, Jie Z, Du H, Wang S, Feng J, Feng M, Kim H-E, Albiol F, Albiol A, Morrell S, Wojna Z, Ahsen ME, Asif U, Jimeno Yepes A, Yohanandan S, Rabinovici-Cohen S, Yi D, Hoff B, Yu T, Chaibub Neto E, Rubin DL, Lindholm P, Margolies LR, McBride RB, Rothstein JH, Sieh W, Ben-Ari R, Harrer S, Trister A, Friend S, Norman T, Sahiner B, Strand F, Guinney J, Stolovitzky G, and the DM DREAM Consortium. Evaluation of combined artificial intelligence and radiologist assessment to interpret screening mammograms. JAMA Network Open 3(3), e200265–e200265 03 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McKinney SM, Sieniek M, Godbole V, Godwin J, Antropova N, Ashrafian H, Back T, Chesus M, Corrado GC, Darzi A, Etemadi M, Garcia-Vicente F, Gilbert FJ, Halling-Brown M, Hassabis D, Jansen S, Karthikesalingam A, Kelly CJ, King D, Ledsam JR, Melnick D, Mostofi H, Peng L, Reicher JJ, Romera-Paredes B, Sidebottom R, Suleyman M, Tse D, Young KC, De Fauw J, and Shetty S International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature 577(7788), 89–94 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kim H-E, Kim HH, Han B-K, Kim KH, Han K, Nam H, Lee EH, and Kim E-K Changes in cancer detection and false-positive recall in mammography using artificial intelligence: a retrospective, multireader study. The Lancet Digital Health (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kopans DB Digital breast tomosynthesis from concept to clinical care. American Journal of Roentgenology (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saarenmaa I, Salminen T, Geiger U, Holli K, Isola J, Kärkkäinen A, Pakkanen J, Piironen A, Salo A, and Hakama M The visibility of cancer on earlier mammograms in a population-based screening programme. European Journal of Cancer 35(7), 1118–1122 7 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ikeda DM, Birdwell RL, O’Shaughnessy KF, Brenner RJ, and Sickles EA Analysis of 172 subtle findings on prior normal mammograms in women with breast cancer detected at follow-up screening. Radiology 226(2), 494–503 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hoff SR, Samset JH, Abrahamsen AL, Vigeland E, Klepp O, and Hofvind S Missed and true interval and screen-detected breast cancers in a population based screening program. Academic Radiology 18(4), 454–460 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fenton JJ, Taplin SH, Carney PA, Abraham L, Sickles EA, D’Orsi C, Berns EA, Cutter G, Hendrick RE, Barlow WE, and Elmore JG Influence of computer-aided detection on performance of screening mammography. New England Journal of Medicine 356(14), 1399–1409 4 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lehman CD, Wellman RD, Buist DS, Kerlikowske K, Tosteson AN, and Miglioretti DL Diagnostic accuracy of digital screening mammography with and without computer aided detection. JAMA Internal Medicine 33(8), 839–841 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Henriksen EL, Carlsen JF, Vejborg IM, Nielsen MB, and Lauridsen CA The efficacy of using computer-aided detection (CAD) for detection of breast cancer in mammography screening: a systematic review. Acta radiologica 60(1), 13–18 1 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tchou PM, Haygood TM, Atkinson EN, Stephens TW, Davis PL, Arribas EM, Geiser WR, and Whitman GJ Interpretation Time of Computer-aided Detection at Screening Mammography. Radiology 257(1), 40–46 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bowser D, Marqusee H, Koussa ME, and Atun R Health system barriers and enablers to early access to breast cancer screening, detection, and diagnosis: a global analysis applied to the MENA region. Public Health 152, 58 – 74 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li J-J, St Louis J, Finkelstein DM, Yu K-D, Chen W-Q, Shao Z-M, and Goss PE Breast cancer in China. The Lancet Oncology 15(7), e279–e289 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Heath M, Kopans D, Moore R, and Kegelmeyer P Jr. The digital database for screening mammography. In The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212–218. Proceedings of the 5th international workshop on digital mammography, (2000). [Google Scholar]

- [30].Halling-Brown MD, Warren LM, Ward D, Lewis E, Mackenzie A, Wallis MG, Wilkinson L, Given-Wilson RM, McAvinchey R, and Young KC OPTIMAM mammography image database: a large scale resource of mammography images and clinical data. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.04742 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [31].Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li L-J, Li K, and Fei-Fei L ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In CVPR, (2009). [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wu K, Wu E, Wu Y, Tan H, Sorensen G, Wang M, and Lotter B Validation of a deep learning mammography model in a population with low screening rates. In Fair ML for Health Workshop. Neural information processing systems, (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sickles E, D’Orsi C, and Bassett L ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, 5th Edition, (American College of Radiology, Reston, VA, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hart D, Shochat E, and Agur Z The growth law of primary breast cancer as inferred from mammography screening trials data. British Journal of Cancer 78(3), 382–387 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weedon-Fekjær H, Lindqvist BH, Vatten LJ, Aalen OO, and Tretli S Breast cancer tumor growth estimated through mammography screening data. Breast Cancer Research 10(3), (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]