Abstract

A five-gene cluster around the gene in Clostridium cellulovorans that encodes endoglucanase EngL, which is involved in plant cell wall degradation, has been cloned and sequenced. As a result, a mannanase gene, manA, has been found downstream of engL. The manA gene consists of an open reading frame with 1,275 nucleotides encoding a protein with 425 amino acids and a molecular weight of 47,156. ManA has a signal peptide followed by a duplicated sequence (DS, or dockerin) at its N terminus and a catalytic domain which belongs to family 5 of the glycosyl hydrolases and shows high sequence similarity with fungal mannanases, such as Agaricus bisporus Cel4 (17.3% identity), Aspergillus aculeatus Man1 (23.7% identity), and Trichoderma reesei Man1 (22.7% identity). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and N-terminal amino acid sequence analyses of the purified recombinant ManA (rManA) indicated that the N-terminal region of the rManA contained a DS and was truncated in Escherichia coli cells. Furthermore, Western blot analysis indicated that ManA is one of the cellulosomal subunits. ManA production is repressed by cellobiose.

Clostridium cellulovorans (ATCC 35296), an anaerobic, mesophilic, and spore-forming bacterium, utilizes not only cellulose but also xylan, pectin, and several other carbon sources (18), produces an extracellular cellulolytic multienzyme complex called the cellulosome (12) with a total molecular weight of about 1 million, and is capable of hydrolyzing crystalline cellulose. The C. cellulovorans cellulosome is comprised of three major subunits that include the scaffolding protein CbpA (17), the endoglucanase EngE (22), and the exoglucanase ExgS (13). In addition to these major subunits, both sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and zymogram analysis indicated the presence of several minor enzymatic subunits (16). Recently, we have found genes for two novel enzymatic subunits, mannanase and pectate lyase, lying in gene clusters of the C. cellulovorans cellulosome (4, 23). Therefore, the identification of the enzymatic subunits associated with the cellulosome indicated that this enzyme complex can degrade not only cellulose, xylan, and lichenan (6, 22) but also mannan and pectin. The present paper provides data that indicate that a cellulosomal gene cluster (the engL gene cluster) in which one of the genes codes for a protein homologous to fungal mannanases exists and that the enzyme encoded by this gene can degrade mannan. Thus, the versatility of the cellulosome to degrade cell wall materials in plants is further established.

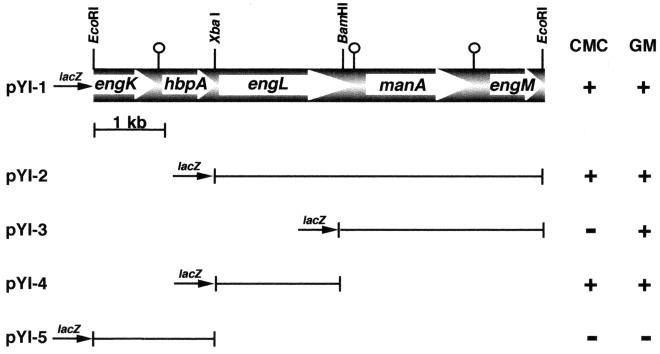

A C. cellulovorans genomic library constructed in λZAPII (22) was immunoscreened with an anti-P120 (endoglucanase) antiserum (diluted 1:500) previously prepared from C. cellulovorans and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody (diluted 1:3,000) (Bio-Rad). Positive clones were further screened for endoglucanase and mannanase activity by overlaying with 0.7% soft agar containing 0.3% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC; low viscosity; Sigma) or 0.25% glucomannan. Colonies having enzyme activity against CMC or glucomannan were recognized by the formation of clear haloes on a red background after staining with 0.1% Congo red and destaining with 1 M NaCl (1). From approximately 20,000 transformants, four positive clones were isolated and further characterized. All clones contained a common 6.8-kb EcoRI insert named pYl-1 (Fig. 1). To determine the coding region of ManA, various subclones were prepared and determined by the formation of clear haloes around the colonies with CMC and glucomannan. These results indicated that the coding region for the manA gene was on the 3.3-kb BamHI-EcoRI (pYl-3) fragment (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Restriction enzyme map of the pYl-1 fragment. The transformants harboring the plasmids with the appropriate deletion were transferred to a Luria-Bertani agar plate. After the colonies grew, agar with 0.3% CMC or 0.25% glucomannan (GM) was poured over the transformants and enzyme activity against CMC or glucomannan was judged by the formation of clear haloes around the colonies (+, visible halo; −, no halo). The genes coding for EngK, EngL, HbpA, ManA, and EngM are shown at the top. The pin-like marks indicate palindromes.

Nucleotide sequence of the manA gene.

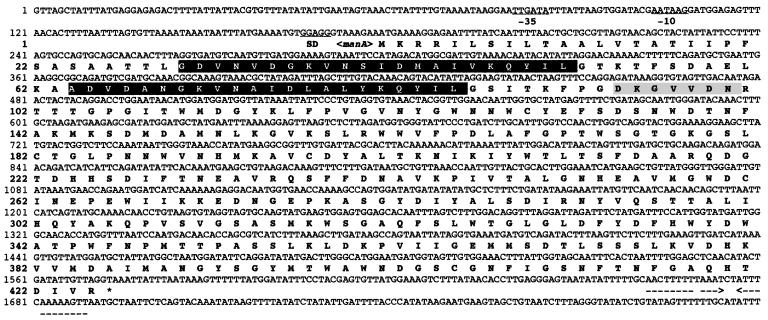

The nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that the pYl-1 fragment contained five different open reading frames (ORFs), i.e., engK-hbpA-engL-manA-engM (Fig. 1). The complete nucleotide and amino acid sequences of manA and ManA, respectively, are shown in Fig. 2. Downstream of the engL gene, the ORF of the manA gene consists of 1,275 nucleotides encoding a protein with 425 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 47,156. The putative initiation codon, ATG, was preceded at a spacing of 7 bp by a typical gram-positive ribosome-binding sequence, GGAGG. Upstream of the coding region, possible promoter sequences, TTGATA for the −35 region and AATAAG for the −10 region, with a 17-bp spacing between them (7), were found. A possible transcription terminator that consists of a 13-bp palindrome, corresponding to an mRNA hairpin loop with a ΔG of −11.8 kcal/mol (ca. −49 kJ/mol) (15), was found downstream of the TAA termination codon.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of manA and ManA, respectively. The putative promoter (−35 and −10) and Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences are underlined. Palindrome sequences are indicated by arrows facing each other. The stop codons are indicated by asterisks. The DSs, or dockerin, in ManA are boxed and in white letters. The chemically determined amino acid sequence of ManA is shaded.

Amino acid sequence similarity of ManA.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of ManA revealed a signal peptide and consensus sequence (Ala-X-Ala-Ala) (24) in which the predicted cleavage site is located between position 25 (Ala) and position 26 (Ala). Removal of the signal peptide yields a mature protein with 400 amino acids and a molecular weight of 44,528. Interestingly, a duplicated sequence (DS, or dockerin) was found in the N terminus (Fig. 2). The DSs consisting of 22-amino-acid repeats are well-conserved in cellulosomal enzymatic subunits in C. cellulovorans and other Clostridium species. A homology search revealed that a catalytic domain (residues 88 to 425) located directly downstream of the DS belongs to family 5 of the glycosyl hydrolases, which include large and growing families comprising not only endoglucanases but also bacterial, fungal, and plant β-mannanases (5). ManA showed high sequence similarity with fungal β-mannanases such as Agaricus bisporus Cel4 (17.3% identity) (26), Aspergillus aculeatus Man1 (23.7% identity) (3), and Trichoderma reesei Man1 (22.7% identity) (19). Recently, β-mannanases have been classified into two distinct families, glycosyl hydrolase families 5 and 26 (9). Clostridium thermocellum CelH, one of the cellulosomal subunits, contains two catalytic domains belonging to both families 5 and 26 (2). Interestingly, C. cellulovorans ManA included a catalytic domain homologous to those of fungal mannanases and a DS, or dockerin, found in several Clostridium spp., while ManA from Vibrio sp. had a bacterial mannanase and a fungal dockerin (21), although both ManAs are from bacteria and belong to the same family of hydrolases, family 5.

Purification and characterization of recombinant ManA.

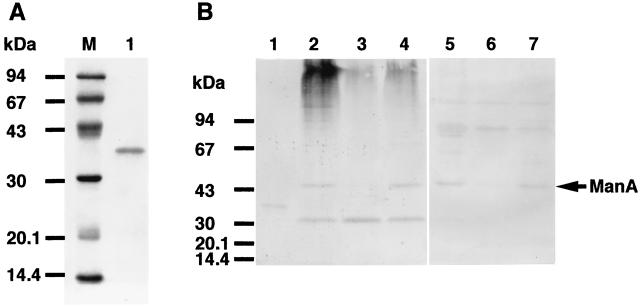

Recombinant ManA (rManA) was purified from the periplasmic fraction of Escherichia coli XL1-Blue harboring pYl-3 with the Q Sepharose Fast Flow column (2.6 by 22 cm; Pharmacia) and Sephacryl S-200 column (2.6 by 75 cm; Pharmacia). After purification and SDS-PAGE, the final preparation yielded a single band and the molecular weight of the enzyme was estimated to be around 38,000 (Fig. 3A). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of recombinant ManA (rManA) was determined by automated Edman degradation with a protein sequencer (model 477; Applied Biosystems) to be Asp-Lys-Gly-Val-Val-Asp-Asn, which is in perfect agreement with the deduced amino acid sequence at positions 94 to 100 (Fig. 2). This result indicated that purified rManA was truncated in E. coli and lacked the N-terminal sequence of 93 amino acids. Therefore, the molecular weight of purified enzyme estimated by SDS-PAGE was in good agreement with the value (37,341), excluding the N-terminal region of ManA, calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the purified ManA by SDS-PAGE (A) and Western blotting (immunoblotting) (B). SDS-PAGE was performed in a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel by the method of Laemmli (11). After electrophoresis, the protein was transferred onto an Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) by electroblotting. Western blot (immunoblot) analysis was performed with an anti-ManA antiserum (diluted 1:500). Lane M, standard markers (Low-Molecular Weight SDS Calibration Kit; Pharmacia) (phosphorylase b [94 kDa], albumin [67 kDa], ovalbumin [43 kDa], carbonic anhydrase [30 kDa], trypsin inhibitor [20.1 kDa], and α-lactalbumin [14.4 kDa]); lanes 1, purified ManA; lane 2, ASC supernatant; lane 3, cellobiose supernatant; lane 4, guar gum supernatant; lane 5, ASC cellulosome; lane 6, cellobiose cellulosome; lane 7, guar gum cellulosome.

C. cellulovorans cells were grown in various media containing different carbon sources to determine whether these carbon sources could affect ManA production. Extracellular ManA production by C. cellulovorans was compared with cultures containing either acid swollen cellulose (ASC), cellobiose, or guar gum. Cellulosomes from C. cellulovorans were prepared as described previously (14). Both culture supernatant and cellulosome fractions were prepared for each substrate and subjected to Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 3B, anti-ManA antibody prepared from the rManA immunoreacted with all culture fractions and some cross-reaction of the antibody was evident with several cellulosome subunits over 67 kDa (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 to 7). With the supernatant fractions (lanes 2 to 4), the immunoreactive bands (45 and 32 kDa) were detected with the ASC or guar gum supernatant (lanes 2 and 4), while only the 32-kDa band was detected with the cellobiose supernatant (lane 3). In contrast to the supernatant fractions, only the 45-kDa band was detected with the ASC or guar gum cellulosome (lanes 5 and 7), while no band was detected on the cellobiose cellulosome (lane 6). On the other hand, the 32-kDa band was not detected on all the cellulosome fractions (lanes 5 to 7) and is presumably a noncellulosomal protein that crossreacts with anti-ManA antibody. The 45-kDa immunoreactive band is in good agreement with the value (44,528), excluding the putative signal peptide, calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence of ManA. These results indicated that the 45-kDa band is identified as ManA and that ManA is one of the cellulosomal subunits. Furthermore, it is likely that ManA production by C. cellulovorans can be repressed by cellobiose (lanes 3 and 6). Thus, Western blot analysis indicated that ManA is one of the cellulosomal subunits and that ManA production is repressed by cellobiose. The cellulosome fractions from ASC and guar gum contained the 45-kDa immunoreactive band, which is in good agreement with the molecular mass calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence of mature ManA (lanes 5 and 7). In addition, it is possible that the 32-kDa protein that exists in all the culture supernatants may be another noncellulosomal mannanase, since it cross-reacts strongly with anti-ManA (lanes 2 to 4).

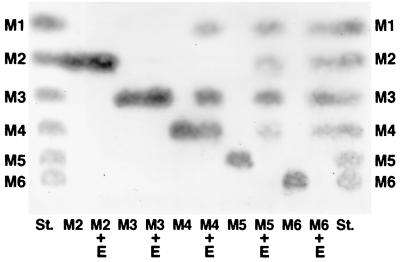

The optimum pH and temperature of purified ManA for activity were 7.0 and 45°C, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the purified rManA revealed greatest activity with glucomannan, followed by about 80% activity on locust bean gum, 20% on guar gum, and 10% on β-mannan, but it did not hydrolyze CMC. These results indicated that ManA could not hydrolyze the β-1,4-cellulosidic linkages but could only hydrolyze the β-1,4-mannosidic linkages. As shown in Fig. 4, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis revealed that purified ManA cleaved M4 to form M3 and M1, but it did not completely hydrolyze it. The main products from M5 were M3 and M1 rather than M4 and M2. Mannohexose (M6) was completely hydrolyzed to produce M4 to M1, but the enzyme did not act on M2 and M3. ManA seems to preferentially hydrolyze the β-1,4-mannosidic linkages situated at the fourth position, followed by the third position from the nonreducing end. Furthermore, the hydrolysis patterns of ManA on TLC analysis showed that the main products from mannooligosaccharides (M4 to M6) produced mostly M1 and M3, followed by M2 and M4, and did not act on M2 and M3. Thus, the properties of ManA differed from those of EngB (6), EngE (22), EngD (6, 8), and EngF (10) in substrates degraded and the products that were formed, although all the enzymes belonged to family 5.

TABLE 1.

Activity of rManA on various substratesa

| Substrate | Sp act (U/mg protein) |

|---|---|

| Glucomannan | 15.6 |

| Guar gum | 3.0 |

| Locust bean gum | 12.9 |

| β-Mannan | 1.6 |

| CMC | 0 |

The assay was performed with 1.0% (wt/vol) substrate and 20 μg of purified rManA in 1.0 ml of 50 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid] buffer (pH 7.0), and it was carried out at 45°C for 10 min. The reducing sugar formed was measured by the method of Somogyi-Nelson (25) with d-mannose as the standard. One unit of polymer hydrolysis presents 1 μmol of reducing sugar liberated per min per mg of protein.

FIG. 4.

TLC of the hydrolysis products of mannooligosaccharides with purified ManA. TLC analysis was performed as previously described (20). Mannooligosaccharides (mannobiose to mannohexose [M2 to M6]) were purchased from Megazyme Ltd. (Sydney, Australia). The reaction mixture contained 20 μg of purified ManA and 20 μg of each mannooligosaccharide (mannobiose to mannohexose [M2 to M6]) in 1 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0) at 37°C for 16 h.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF132735.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Araki for providing us with β-mannan and glucomannan.

The research was supported in part by grant DE-DDF03-92ER20069 from the U.S. Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali B R S, Romaniec M P M, Hazlewood G P, Freedman R B. Characterization of the subunits in an apparently homogeneous subpopulation of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomes. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1995;17:705–711. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(94)00118-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer E A, Shimon L J W, Shoham Y, Lamed R. Cellulosomes—structure and ultrastructure. J Struct Biol. 1998;124:221–234. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christgau S, Kauppinen S, Vind J, Kofod L V, Dalbøge H. Expression cloning, purification and characterization of a β-1,4-mannanase from Aspergillus aculeatus. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;33:917–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doi R H, Park J-S, Liu C-C, Malburg L M, Tamaru Y, Ichi-ishi A, Ibrahim A. Cellulosome and noncellulosomal cellulases of Clostridium cellulovorans. Extremophiles. 1998;2:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s007920050042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ethier N, Talbot G, Sygusch J. Gene cloning, DNA sequencing, and expression of thermostable β-mannanase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4428–4432. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4428-4432.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foong F, Doi R H. Characterization and comparison of Clostridium cellulovorans endoglucanase-xylanase EngB and EngD hyperexpressed in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1403–1409. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1403-1409.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Prokaryotic promoters in biotechnology. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 1995;1:105–128. doi: 10.1016/s1387-2656(08)70049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamamoto T, Foong F, Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Analysis of functional domains of endoglucanases from Clostridium cellulovorans by gene cloning, nucleotide sequencing and chimeric protein construction. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:472–479. doi: 10.1007/BF00292718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1993;293:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ichi-ishi A, Sheweita S, Doi R H. Characterization of EngF from Clostridium cellulovorans and identification of a novel cellulose binding domain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1086–1090. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1086-1090.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamed R, Bayer E A. The cellulosome concept: exocellular and extracellular enzyme factor centers for efficient binding and cellulolysis. In: Aubert J-P, Béguin P, Millet J, editors. Biochemistry and genetics of cellulose degradation. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1988. pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C-C, Doi R H. Properties of exgS, a gene for a major subunit of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. Gene. 1998;211:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matano Y, Park J-S, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Cellulose promotes extracellular assembly of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosomes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6952–6956. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6952-6956.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg M, Court D. Regulatory sequences involved in the promotion and termination of RNA transcription. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:319–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Essential 170 kDa subunit for degradation of crystalline cellulose of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2192–2195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoseyov O, Takagi M, Goldstein M, Doi R H. Primary sequence analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein A (CbpA) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3483–3487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sleat R, Mah R A, Robinson R. Isolation and characterization of an anaerobic, cellulolytic bacterium, Clostridium cellulovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:88–93. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.88-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stålbrand H, Saloheimo A, Vehmaanperä J, Henrissat B, Penttilä M. Cloning and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of a Trichoderma reesei β-mannanase gene containing a cellulose binding domain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1090–1097. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.1090-1097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamaru Y, Araki T, Amagoi H, Mori H, Morishita T. Purification and characterization of an extracellular β-1,4-mannanase from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain MA-138. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4454–4458. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4454-4458.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamaru Y, Araki T, Morishita T, Kimura T, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. Cloning, DNA sequencing, and expression of the β-1,4-mannanase from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain MA-138. J Ferment Bioeng. 1997;83:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamaru Y, Doi R H. Three surface layer homology domains at the N terminus of the Clostridium cellulovorans major cellulosomal subunit EngE. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3270–3276. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3270-3276.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamaru Y, Liu C-C, Malburg L, Doi R H. The Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome and non-cellulosomal cellulases. In: Ohmiya K, Hayashi K, Sakka K, Kobayashi Y, Karita S, Kimura T, editors. Genetics, biochemistry and ecology of cellulose degradation. Tokyo, Japan: Uni Publishers; 1999. pp. 488–494. [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Heijne G. Signal sequences. The limits of variation. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood W A, Bhat K M. Methods for measuring cellulase activities. Methods Enzymol. 1988;160:87–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yagüe E, Mehak-Zunic M, Morgan L, Wood D A, Thurston C F. Expression of CEL2 and CEL4, two proteins from Agaricus bisporus with similarity to fungal cellobiohydrolase I and β-mannanase, respectively, is regulated by the carbon source. Microbiology. 1997;143:239–244. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]