Microorganisms in the environment encounter a varied and not invariably benign diet. The primary suppliers of nutrients for microorganisms are plants. Consumers such as fungi and bacteria do not act singly and often offer plants a return on their investment. Fixed nitrogen and scavenged minerals are examples of specific contributions that microorganisms provide plants as a payback for nutritional supply. Such relationships require chemical specificity because microbial interlopers are prepared to accept the reward without providing the return. Chemicals or mixtures of chemicals can be produced by organisms as either inducements or deterrents, and microorganisms will vary in their response. So successful adaptation requires ongoing shifts in chemical communication among plants and microorganisms. As is true in the rest of biology, the illusion of constancy is achieved at the cost of constant change. Evolutionary acquisition must be accompanied by the capacity for rapid revision of objectives.

Among the first to appreciate the nutritional versatility of microorganisms was den Dooren de Jong (9) who classified Pseudomonas isolates largely on the basis of the range of chemical substrates that would support their growth. The capabilities of these organisms were appreciated by biochemists who saw in them a source of enzymes that challenged the conventions of central metabolism. The swift adaptations of the organisms were of interest to physiologists who sought to understand mechanisms governing synthesis of specialized enzymes for catabolic pathways (38, 39). One of these physiologists, Roger Stanier, recognized that scientific enthusiasm for the traits of Pseudomonas in general had clouded appreciation of the individual organisms that express these traits. If scientists were to generalize about a trait that they had observed, it was necessary to have a sense of what kind of organism expressed the trait. The general capabilities of Pseudomonas are great, but one organism, limited by its size and genetic information, is obliged to be a specialist. Collections of specialists with shared traits form taxa about which accurate predictions can be made. By returning to taxonomy, the art of prediction of many biological traits by observation of a few, Stanier saw the opportunity to define the individual subsets that form the collective whole of Pseudomonas and, as it turned out, beyond.

The landmark investigation of Stanier, Palleroni, and Doudoroff (40) built upon the foundations established by den Dooren de Jong and demonstrated more or less sharply defined taxa. In retrospect, it is evident that taxonomy is a snapshot of evolution. Organisms build upon what went before, and shaped by common ancestry and overlapping selective pressures, groups of organisms formed taxonomic constellations within the genus then known as Pseudomonas. Indeed, some of the groups were sufficiently distinctive to warrant their subsequent assignment to separate genera such as Burkholderia and Comomonas.

Among the bacterial strains in the original Stanier collection were some that did not fit the morphological description of Pseudomonas: these bacteria tended to be paired nonmotile cocci, rather than the typical monoflagellate rods. This trait alone warranted separate generic status, and Baumann was able to classify the organisms in the genus Moraxella, now known as Acinetobacter (3). The nutritional versatility of Acinetobacter matches but does not mirror that of Pseudomonas, and Baumann was able to design procedures for specific selection of Acinetobacter strains from the environment. He showed that the minimum population of these organisms in soil or water samples is 105 viable cells/g, a demonstration of the ubiquity of Acinetobacter in nature (2).

Molecular evidence, particularly 16S RNA nucleotide sequences, were in accord with separate generic assignments for many of the organisms in the genus formerly known as Pseudomonas and revealed a startling paradox. Remaining members of Pseudomonas, centered upon members of the fluorescent group, contain 16S RNA quite similar to that of Acinetobacter, and the latter organisms are placed in the Pseudomonas group in the gamma subdivision of proteobacteria in the National Center for Biotechnology Information taxonomy homepage. Ribosomes aside, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter are quite different in morphology, motility, the G+C content of their DNA, chromosomal organization, and as described below, ecology.

In order to explore the discontinuities that separate bacterial taxa, we have focused attention upon a single metabolic system, the β-ketoadipate pathway. The pathway is widespread among terrestrial microorganisms because it allows utilization of growth substrates, such as aromatic and hydroaromatic compounds, that are produced abundantly by plants. Central reactions of the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway are shown in Fig. 1. The most thorough understanding of the pathway in Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter has been obtained with one representative from each group. Pseudomonas putida PRS1, the type strain for the species, was used by Stanier's group to establish the biochemical outlines of the β-ketoadipate pathway (29) which subsequently has been the target of numerous physiological and genetic investigations (21, 32). Acinetobacter strain ADP1 (BD413) thus far has resisted subclassification within this taxonomically turbulent genus. Originally isolated by Juni, it was shown by him to be highly competent for natural transformation (23), and further, he showed that transformation of a trpE mutant of this strain yielded prototrophs when any other member of the genus served as a donor (22).

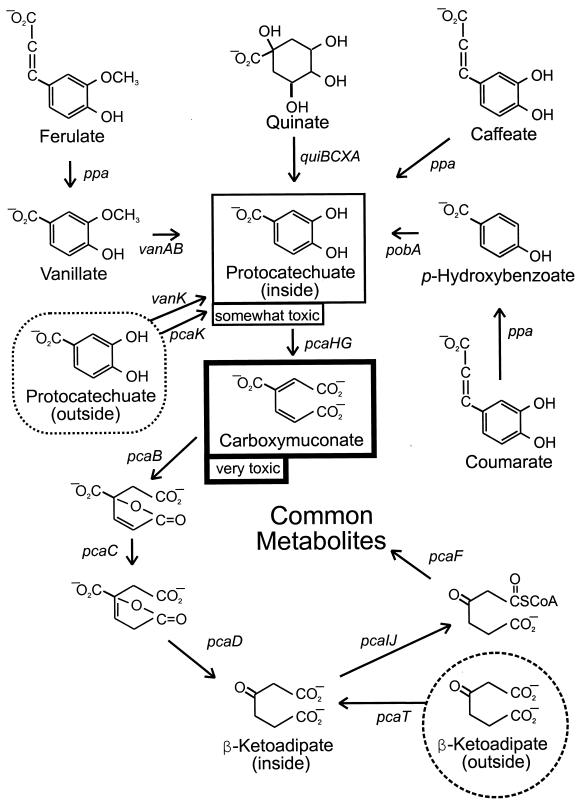

FIG. 1.

Central reactions of the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway in bacteria. Metabolic steps or sequences are represented by designations for the associated genes. Plant products such as quinate and phenylpropenoid compounds (ferulate, caffeate, and coumarate) are metabolized to protocatechuate (in the box with the thin black border). Enzymes encoded by the pca genes convert protocatechuate to common metabolites. The intermediate carboxymuconate (in the box with the thick black border) is very toxic, and cells lacking a functional pcaB fail to grow when protocatechuate or metabolic precursors of this compound are added to growth media. Secondary mutations preventing formation of carboxymuconate from aromatic compounds can be selected, which has facilitated genetic analysis of vanAB, pobA, and pcaHG. Exposure of cells to high concentrations of protocatechuate also impedes growth, and characterization of strains resisting this toxicity led to discovery of functions associated with the transporters VanK and PcaK in Acinetobacter. The β-ketoadipate transporter encoded by pcaT is found in fluorescent Pseudomonas species and has no known counterpart in Acinetobacter.

The genetic system developed by Juni has been of great assistance in analysis of the β-ketoadipate pathway, and further convenience has been provided by the evident toxicity of carboxymuconate, the product of protocatechuate oxygenase (Fig. 1). Mutations knocking out PcaB, the enzyme that acts upon carboxymuconate, prevent the growth of cells with succinate if either protocatechuate or p-hydroxybenzoate (Fig. 1) is added to the growth medium (17). Secondary mutations blocking metabolism of these compounds allow growth with another carbon source in their presence. Thus, strains lacking PcaB have opened opportunities for analysis of mutants defective in catabolism of protocatechuate (8, 14), p-hydroxybenzoate (10, 13), and their metabolic precursors (37; M. A. Smith, G. Huang, D. M. Young, and L. N. Ornston, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. abstr. K-148, p. 350, 1998).

It is clear that Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas called upon the same pool for genes for the β-ketoadipate pathway. Isofunctional proteins from the two genera usually share amino acid sequence identities of about 50% despite the fact that the genes for these enzymes usually have diverged by more than 12% in the G+C content of their DNA. It is also clear that the chromosomal organization of the respective sets of genes is entirely different. Comparison of the pca gene order (Fig. 2) shows that only three pairs of genes (pcaIJ, pcaBD, and pcaHG) retain the same configuration, and two of the pairs (pcaIJ and pcaHG) encode separate subunits of a single enzyme. Shuffling of the genes has been nearly maximized, although their overall clustering is largely preserved. The selective benefit of the shuffling is unknown but would minimize opportunities for recombination between homologous sets of genes (16). It is possible that shuffling is favored at a point in evolutionary divergence where the benefits of recombination are outweighed by the detriments (24).

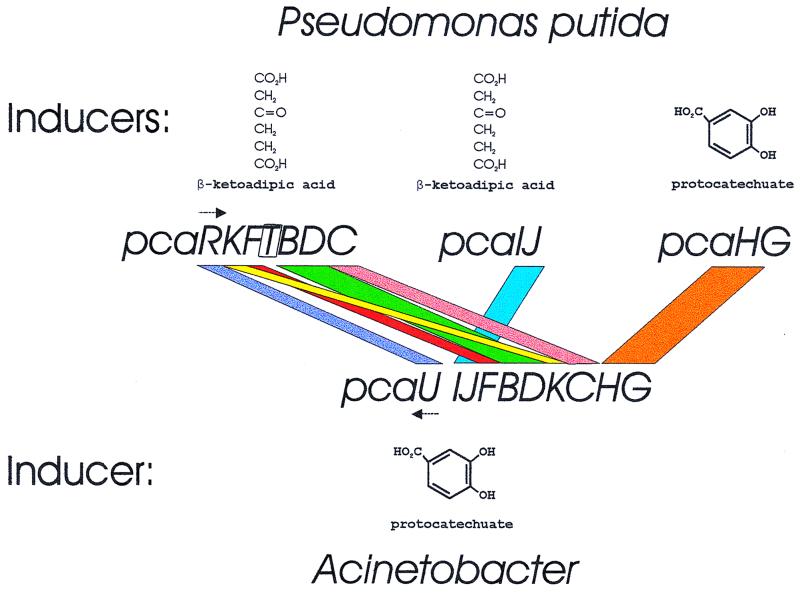

FIG. 2.

Organization of genes for protocatechuate catabolism in P. putida and Acinetobacter. The structures of inducing metabolites are shown. Arrows indicate the transcriptional activator genes pcaR and pcaU. They encode proteins that are similar in sequence and bind to similar operators, but the proteins respond to different inducers.

Acinetobacter and P. putida are also distinguished by the metabolites they use to govern expression of the pca genes (5). In Acinetobacter, all of the pca structural genes are in a single operon that is expressed in response to protocatechuate (Fig. 2). Insofar as is known, the only P. putida genes expressed in response to protocatechuate are pcaHG, the structural genes for protocatechuate oxygenase. In contrast to Acinetobacter, P. putida employs β-ketoadipate as a regulatory metabolite that induces all of the enzymes in the protocatechuate pathway except the oxygenase.

Among the P. putida genes is pcaT which has no known counterpart in Acinetobacter. The function of pcaT is subtle, and discovery of its activity emerged from a false premise about the organization of the pca genes. The regulatory functions of β-ketoadipate were known, and it seemed likely that all of the pca genes save pcaHG formed a regulon that might be expressed collectively in a constitutive mutant. β-Ketoadipate was available, so it was possible to select for strains that grew with the compound without an induction lag after transfer from growth medium containing succinate. Demand for growth with β-ketoadipate was unusual because Stanier (38, 39) had demonstrated that it did not readily permeate the cell membrane. Slow growth with β-ketoadipate occurred, so it was possible to select strains with the desired phenotype (33).

The presumed targets of the selection were pcaIJ, genes for the coenzyme A transferase that acts upon β-ketoadipate, and the presumption was that shared regulation would cause constitutive expression of pcaB, pcaC, and pcaD. Indeed these three genes were expressed constitutively in the selected strains, but mysteriously, pcaIJ were not. What was the target of the selection for rapid adaptation to β-ketoadipate as a growth substrate? After some brooding, we entertained the possibility that we had selected for constitutive expression of a β-ketoadipate transport system, now known to be the product of pcaT, and that this gene shared biosynthetic regulation with pcaB, pcaC, and pcaD. This hypothesis required suspension of disbelief because of the known permeability barriers to β-ketoadipate but was easily tested because adipate, available in radiochemical form, is not utilized effectively by wild-type P. putida (33).

Quite remarkably, the constitutive mutant strains, unlike wild-type cells, rapidly and effectively concentrated radioactive adipate. β-Ketoadipate was a strong competitive inhibitor of the process, an observation compatible with the interpretation that it was the natural substrate of the transport system now known as PcaT. This conclusion has subsequently been confirmed by sequence evidence that pcaT is clustered with other genes associated with the β-ketoadipate pathway in the pcaTBDC operon of P. putida (21; G. W. Buck, Z. Guo, and J. E. Houghton, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. K-158, p. 352). These genes are separated from pcaIJ in the chromosome (Fig. 2).

A selective benefit from the β-ketoadipate transport system is indicated by its broad distribution within the genus Pseudomonas (27), and we are left with the question of its function. Permeability barriers preclude utilization of β-ketoadipate as a robust growth substrate, so what is the contribution of a transport system that concentrates the compound? Clues emerge from the regulation of PcaT. Constitutive synthesis of the transport system is strongly repressed by readily utilized growth substrates such as succinate and acetate, and exposure of cells to these compounds also inhibits the activity of PcaT (28). Expression of PcaT in constitutive strains rises as cells go into stationary phase and remains elevated for weeks in starved cells. A deleterious consequence is that exposure of such cells to the nonmetabolizable analog adipate kills them, presumably as a result of the demand for energy to support gratuitous transport activity (20).

The observed regulation of the activity of PcaT is consistent with its function as a scavenging system used by starved cells to assimilate β-ketoadipate from the environment. Since P. putida is motile, the compound also may serve as a chemoattractant for the bacteria. The implication that β-ketoadipate is a nutrient for some bacteria in the environment was fortified by observation that wild-type Bradyrhizobium spp. constitutively express a high level chemoattraction system for β-ketoadipate (35). These slow-growing bacteria also constitutively express pcaIJ, genes for the enzyme that acts upon β-ketoadipate, at a level comparable to that found in fully induced cultures of the rapidly growing P. putida (33). In contrast, the possibility that β-ketoadipate may serve as the sole nutrient for Acinetobacter in the environment appears to be precluded by the fact that growth of these bacteria with the compound as the sole carbon source requires a mutation leading to constitutive expression of genes with pcaIJ activity (6).

At first glance, the toxic metabolite carboxymuconate might seem to be an unlikely nutrient in the environment, but as with PcaT, analysis of mutant P. putida strains revealed an inducible transporter for the compound (26). The notion that carboxymuconate supports the growth of microorganisms in the environment is fortified by the observation that members of the genus Comomonas grow with carboxymuconate which is not formed by these bacteria during growth with protocatechuate (30).

The motility of P. putida yielded the first evidence for a biological function associated with a member of what has grown to be a large family of transport proteins associated with the β-ketoadipate pathway. Mutations blocking attraction of P. putida to p-hydroxybenzoate were demonstrated to be in pcaK, a gene with sequence matching that of known transport proteins. The mutations also reduced transport of p-hydroxybenzoate into the cells, although it was necessary to elevate the pH in order to demonstrate this effect in the laboratory. At lower pH, the transport system may facilitate growth with low levels of p-hydroxybenzoate (19).

The sequence of P. putida pcaK closely matches that of an Acinetobacter gene also designated pcaK, and each gene is linked to other genes associated with protocatechuate catabolism (Fig. 2). The Acinetobacter gene was blocked fortuitously by the ΔpcaBDK1 deletion designed to cause intracellular accumulation of carboxymuconate from protocatechuate (17, 18). As indicated in Fig. 1, the mutation prevents growth of Acinetobacter in the presence of p-hydroxybenzoate or protocatechuate and has been useful in analysis of genes required for the first steps in catabolism of these compounds. A different pattern emerged when the mutant cells were exposed to quinate (Fig. 1) and succinate. Numerous small colonies emerged on this medium, but contrary to expectation, none of the mutations in these colonies mapped in the region containing genes known to be required for quinate catabolism (11). Upon further investigation, it became evident that the mutations were in a chromosomally distant region containing van genes associated with demethylation of vanillate to protocatechuate (37).

The van genes are unstable. This conclusion emerged from characterization of Acinetobacter ΔpcaBDK1 secondary mutants which grew with succinate in the presence of protocatechuate. As expected, such cells usually were blocked in pcaHG, the structural genes for protocatechuate oxygenase (14). Unexpectedly, about 20% of these cells contained additional mutations preventing conversion of vanillate to protocatechuate (37). This fostered the interpretations that protocatechuate is somewhat toxic in its own right and that inactivation of van genes helped to protect cells against protocatechuate that had been provided in the growth medium. The premise that the van genes are genetically unstable was fortified by characterization of the genes from strains that had acquired spontaneous defects in vanAB, the structural genes for vanillate demethylase. The genes proved to be susceptible to deletions and rearrangements to which two recently characterized mobile elements, IS1236 and Tn5613, contribute. Any Acinetobacter population of significant size contains strains blocked in vanillate demethylation. Such cells are bioreactors that convert the common environmental chemical ferulate to vanillate (37).

Near vanAB in the Acinetobacter chromosome are two genes that, on the basis of sequence comparisons, appear to be associated with transfer of exogenous compounds into the cell. One of the sequenced genes matches known porins. The other, directly upstream from the putative porin, is vanK, which is closely related to pcaK, mucK, and benK, other genes for transporters known to be associated with the β-ketoadipate pathway. Mutants blocked in the transporters encoded by vanK and pcaK are severely impeded in their ability to grow with quinate, and such cells accumulate protocatechuate in the medium when exposed to quinate. Restoration of wild-type vanK or pcaK to such cells restores their ability to grow with quinate (7).

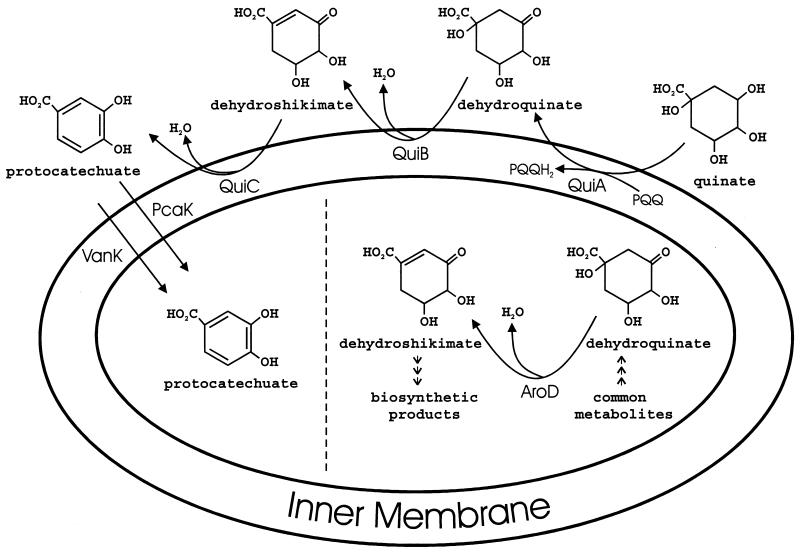

These findings are consistent with the interpretation that the first three steps of quinate metabolism, conversion of quinate to protocatechuate, take place on the outer surface of the inner cell membrane (Fig. 3). This allows compartmentation of catabolic enzymes that act upon shikimate and dehydroshikimate so that these biosynthetic intermediates do not trigger their catabolism in the absence of an exogeneous supply. The cells' response to protocatechuate also depends upon how it is supplied. Low concentrations of the compound can support vigorous growth, and the organism forms two transport systems (PcaK and VanK) which can move the molecule into the cell under these circumstances. Transcriptional regulation of pcaK and pcaHG is unified (Fig. 2), so the transport activity of PcaK is balanced with the activity of the enzyme that removes protocatechuate as it enters the cell.

FIG. 3.

Compartmentation of quinate catabolism in Acinetobacter. Mutations blocking both pcaK and vanK impede growth with quinate, and cells containing these mutations accumulate protocatechuate in the growth medium. Thus, in accord with earlier suggestions, the initial steps in quinate utilization appear to take place on the outer surface of the inner cell membrane. Not shown in the figure is shikimate which is catabolized directly to dehydroshikimate by QuiA. Compartmentation keeps catabolic enzymes that act upon shikimate and dehydroshikimate physically separate from enzymes that must supply these compounds as biosynthetic intermediates under all growth conditions.

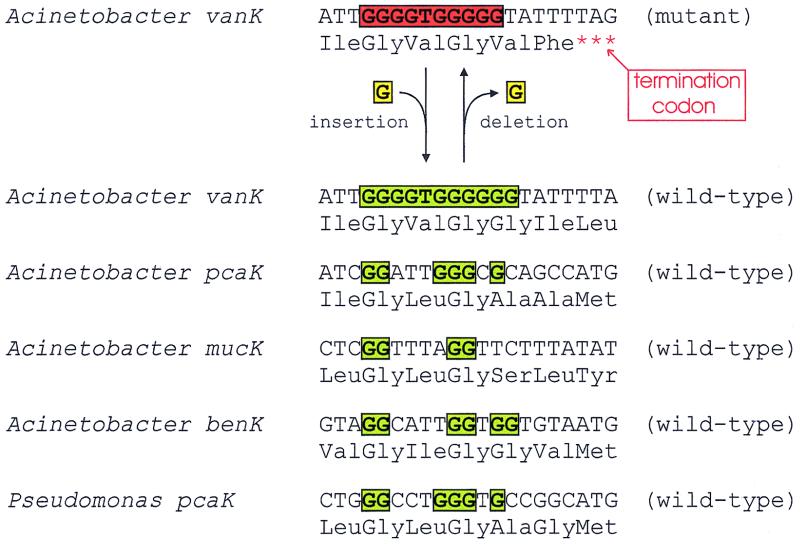

A different kind of balance is achieved with vanK (7). Most spontaneous mutations inactivating this gene abbreviate a homopolymeric G tract within vanK by one residue (Fig. 4). Reversion of such mutants occurs frequently, and any Acinetobacter population contains a mixture of cells. Some contain an active VanK and are prepared to pump protocatechuate into cells when this growth substrate is available at low concentrations. Other cells lack a functional VanK and therefore can resist the potentially toxic effect of the compound when it is provided in high concentrations. Comparison of the vanK nucleotide sequence with those of related transport systems (Fig. 4) shows that the homopolymeric G tract, the basis of genetic instability, was acquired by vanK during its evolutionary divergence from the other transport genes. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the G tract has selective benefit. Intriguingly, the genetic oscillation of vanK may contribute to the evolutionary stability of Acinetobacter cell lines that either use VanK or fail to use VanK depending upon the supply of protocatechuate.

FIG. 4.

Frequent mutations causing loss or gain of vanK function in Acinetobacter. The gene acquired a homopolymeric G tract during its evolutionary divergence from related transporters. Evidently slippage during replication can cause loss of a G residue from the tract. This mutation introduces a stop codon directly downstream from the G tract. The deletion reverts readily, so most populations of the Acinetobacter cell line have a mixture of wild-type cells and cells containing the deletion mutation.

Adaptation of cells to different concentrations of a potentially toxic growth substrate illustrates a core strategy of catabolism: how to obtain compounds that are beneficial without accumulating compounds that are detrimental. In this context, it is important to remember that growth substrates are provided singly only in the laboratory. Even in these cases, the concentrations of potential growth substrates may exceed the threshold of toxicity and, by preventing growth, may mask the ability of organisms to utilize the compounds (34). Additional challenges may be introduced into the environment by toxic chemicals with structures mimicking those of established growth substrates.

Mixtures of compounds are released by plants, and mixtures of genes are required for microorganisms to respond. This necessity may help to account for supraoperonic clustering of some genes for catabolic pathways in bacterial chromosomes. A contributing factor to such clustering may be horizontal transfer (25), but other selective forces may be at work as well. One such force is the possibility for coamplification by duplication of genes that are called into play at the same time (1, 8).

Whatever the selective forces favoring clustering, the Acinetobacter pca genes provide part of a rich example. To one side of the pca operon are genes associated with catabolism of diverse compounds (11, 12; Smith et al., Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.) such as quinate, shikimate, and phenylpropenoids (e.g., ferulate), all of which form protocatechuate during their metabolism. To the other side of the pca operon is a cluster of genes associated with catabolism of dicarboxylic acids (D. Parke, M. A. Garcia, and L. N. Ornston, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. K-25a, p. 405). All of these compounds share the property of being chemically bifunctional in that they can form a vast array of ether and ester bonds as found, respectively, in the plant products lignin and suberin (4). The importance of lignin is widely appreciated because there is a lot of it: its ether bonds are difficult to break. However, a material need not be abundant in order to be metabolically significant, and turnover of the biochemically accessible suberin in the environment may well exceed that of lignin.

As characterization of chromosomal clusters of catabolic genes proceeds, attention will be drawn increasingly to genes for filters and pumps (porins [15] and transporters [31]) that often emerge as components of catabolic systems. Additional components are genes for efflux pumps with an ancient evolutionary history and now notable for their contributions to antibiotic resistance (36). Unravelling the contributions of all of these biomolecules will be a challenging task because of their overlapping specificities in the laboratory. The story may be different in the natural environment where populations of cells must adapt to a shifting dietary blend. The cell surface is where the rubber hits the road in bacterial evolution.

As this case study illustrates, questions about metabolism need not be limited to what it is. We also need to know where it came from, where it is, and when it is. Someday we may learn why it is. Some years past, the study of metabolism fell out of fashion because its fundamental mechanics appeared to have been understood. The same could have been said of the piano more than two centuries ago, but the diverse ways in which it can be played continued to be a source of creativity, fascination, and delight. So too with metabolism, two centuries hence.

Acknowledgments

Research in our laboratory has been supported by grants DAAG55-98-0232 from the Army Research Office and MCB-9603980 from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Publication 22 from the Biological Transformation Center in the Yale Biospherics Institute.

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson D I, Slechta E S, Roth J R. Evidence that gene amplification underlies adaptive mutability of the bacterial lac operon. Science. 1998;282:1133–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann P. Isolation of Acinetobacter from soil and water. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:39–42. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.1.39-42.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann P, Doudoroff M, Stanier R Y. A study of the Moraxella group. II. Oxidative-negative species (genus Acinetobacter) J Bacteriol. 1968;95:520–541. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.5.1520-1541.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernards M A, Lewis N G. The macromolecular aromatic domain in suberized tissue: a changing paradigm. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:915–933. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)80052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canovas J L, Ornston L N, Stanier R Y. Evolutionary significance of metabolic control systems. The β-ketoadipate pathway provides a case history in bacteria. Science. 1967;156:1695–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3783.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canovas J L, Wheelis M L, Stanier R Y. Regulation of the enzymes of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Moraxella calcoacetica. 2. The role of protocatechuate as inducer. Eur J Biochem. 1968;3:293–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb19529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Argenio D A, Segura A, Coco W M, Bunz P V, Ornston L N. The physiological contribution of Acinetobacter PcaK, a transport system that acts upon protocatechuate, can be masked by the overlapping specificity of VanK. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3505–3515. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3505-3515.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Argenio D A, Vetting M W, Ohlendorf D H, Ornston L N. Substitution, insertion, deletion, suppression, and altered substrate specificity in functional protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenases. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6478–6487. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6478-6487.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Dooren de Jong L E. Bijdrage tot de kennis van het mineralisatieproces. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Nijgh and van Ditmar; 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMarco A A, Averhoff B A, Kim E E, Ornston L N. Evolutionary divergence of pobA, the structural gene encoding p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in an Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain well-suited for genetic analysis. Gene. 1993;125:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90741-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsemore D A, Ornston L N. The pca-pob supraoperonic cluster of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus contains quiA, the structural gene for quinate-shikimate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7659–7666. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7659-7666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elsemore D A, Ornston L N. Unusual ancestry of dehydratases associated with quinate catabolism in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5971–5978. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5971-5978.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerischer U, D'Argenio D, Ornston L N. IS1236, a newly discovered member of the IS3 family, exhibits varied patterns of insertion into the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus chromosome. Microbiology. 1996;142:1825–1831. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerischer U, Ornston L N. Spontaneous mutations in pcaH and -G, structural genes for protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1336–1347. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1336-1347.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock R E. Resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S93–S99. doi: 10.1086/514909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartnett C, Neidle E L, Ngai K L, Ornston L N. DNA sequences of genes encoding Acinetobacter calcoaceticus protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: evidence indicating shuffling of genes and of DNA sequences within genes during their evolutionary divergence. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:956–966. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.956-966.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartnett G B, Averhoff B, Ornston L N. Selection of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus mutants deficient in the p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase gene (pobA), a member of a supraoperonic cluster. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6160–6161. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6160-6161.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartnett G B, Ornston L N. Acquisition of apparent DNA slippage structures during extensive evolutionary divergence of pcaD and catD genes encoding identical catalytic activities in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Gene. 1994;142:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood C S, Nichols N N, Kim M K, Ditty J L, Parales R E. Identification of the pcaRKF gene cluster from Pseudomonas putida: involvement in chemotaxis, biodegradation, and transport of 4-hydroxybenzoate. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6479–6488. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6479-6488.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harwood C S, Ornston L N. Futile high-level transport activity impairs starvation-survival of Pseudomonas putida. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2421–2427. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harwood C S, Parales R E. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juni E. Interspecies transformation of Acinetobacter: genetic evidence for a ubiquitous genus. J Bacteriol. 1972;112:917–931. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.2.917-931.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juni E, Janik A. Transformation of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Bacterium anitratum) J Bacteriol. 1969;98:281–288. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.1.281-288.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowalchuk G A, Hartnett G B, Benson A, Houghton J E, Ngai K L, Ornston L N. Contrasting patterns of evolutionary divergence within the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus pca operon. Gene. 1994;146:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90829-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence J G, Roth J R. Selfish operons: horizontal transfer may drive the evolution of gene clusters. Genetics. 1996;143:1843–1860. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.4.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meagher R B, McCorkle G M, Ornston M K, Ornston L N. Inducible uptake system for β-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate in a permeability mutant of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1972;111:465–473. doi: 10.1128/jb.111.2.465-473.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ondrako J M, Ornston L N. Biological distribution and physiological role of the β-ketoadipate transport system. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;120:199–209. doi: 10.1099/00221287-120-1-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ornston L N, Parke D. Properties of an inducible uptake system for β-ketoadipate in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:475–488. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.2.475-488.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornston L N, Stanier R Y. The conversion of catechol and protocatechuate to β-ketoadipate by Pseudomonas putida. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3776–3786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ornston M K, Ornston L N. The regulation of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Pseudomonas acidovorans and Pseudomonas testosteroni. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;73:455–464. doi: 10.1099/00221287-73-3-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pao S S, Paulsen I T, Saier M H., Jr Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parke D. Acquisition, reorganization, and merger of genes—novel management of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parke D, Ornston L N. Constitutive synthesis of enzymes of the protocatechuate pathway and of the β-ketoadipate uptake system in mutant strains of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:272–281. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.1.272-281.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parke D, Ornston L N. Nutritional diversity of Rhizobiaceae revealed by auxanography. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:1743–1750. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parke D, Rivelli M, Ornston L N. Chemotaxis to aromatic and hydroaromatic acids: comparison of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Rhizobium trifolii. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:417–422. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.417-422.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saier M H, Jr, Paulsen I T, Martin A. A bacterial model system for understanding multi-drug resistance. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:289–295. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segura A, Bunz P V, D'Argenio D A, Ornston L N. Genetic analysis of a chromosomal region containing vanA and vanB, genes required for conversion of either ferulate or vanillate to protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3494–3504. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3494-3504.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanier R Y. Problems of bacterial oxidative metabolism. Bacteriol Rev. 1950;14:179–191. doi: 10.1128/br.14.3.179-191.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanier R Y. Simultaneous adaptation: a new technique for the study of metabolic pathways. J Bacteriol. 1950;54:339–348. doi: 10.1128/jb.54.3.339-348.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanier R Y, Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;43:159–271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]