Abstract

In many parts of the world, numerous outbreaks of pertussis have been described despite high vaccination coverage. In this article we report the epidemiological characteristics of pertussis in Brazil using a Surveillance Worksheet. Secondary data of pertussis case investigations reported from January 1999 to December 2008 recorded in the Information System for Notifiable Diseases (SINAN) and the Central Laboratory for Public Health (LACEN-MS) were utilized. The total of 561 suspected cases were reported and 238 (42.4%) of these were confirmed, mainly in children under six months (61.8%) and with incomplete immunization (56.3%). Two outbreaks were detected. Mortality rate ranged from 2.56% to 11.11%. The occurrence of outbreaks and the poor performance of cultures for confirming diagnosis are problems which need to be addressed. High vaccination coverage is certainly a good strategy to reduce the number of cases and to reduce the impact of the disease in children younger than six months.

Keywords: Whooping cough, Pertussis, Epidemiology, Bordetella pertussis, Outbreak investigation

Introduction

Pertussis is an acute infection of the respiratory tract with a growing number of people at risk of contracting the disease in many parts of the world.1 Even after the decrease in prevalence following the advent of the Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis (DTP) vaccine, pertussis has remained a significant public health problem. Globally, an estimated overall annual incidence of 50 million cases, 95% of them in developing countries,1 and approximately 300,000 deaths have been caused by this disease, with a mortality rate of around 1% in developing countries and 0.04% in developed countries.2

In many parts of the world, numerous outbreaks of pertussis have been described despite high vaccination coverage.3, 4, 5 In this article, we report the epidemiological characteristics of pertussis in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

Materials and methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional and retrospective study included all Pertussis Surveillance Worksheet used from January 1999 to December 2008 to report pertussis suspected cases to the Health Department of the State of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. The data were collected from worksheets after local institutional review board approval.

The Brazilian vaccination scheme against Bordetella pertussis is composed by three doses at two, four and six months with the first booster at 6 to 12 months after the third dose and second booster at four to six years.6

It was used the terms established by the Brazilian Ministry of Health6 for the case definition. Suspected case – every individual presenting dry cough for 14 days or more associated with one or more of the following symptoms: paroxysmal cough – sudden uncontrollable cough, with 5–10 quick and short coughs in a single exhalation; inspiratory whoop, post-cough vomiting; or having a history of contact with a pertussis case confirmed by clinical criteria.

Confirmed case: (a) by laboratorial criteria: isolation of Bordetella pertussis; (b) by epidemiological criteria: any suspected case which has had contact with a pertussis confirmed case by laboratory testing, between the beginning of the catarrhal period up to three weeks after onset of the disease paroxysmal period; (c) by clinical criteria: every suspected case of pertussis whose hemogram shows leukocytosis (over 20,000 leukocytes/mm3) and absolute lymphocytosis (over 10,000 leukocytes/mm3) and negative or not performed culture; and absence of epidemiological linkage; and no confirmation of another etiology.

Excluded case: any suspected case that does not conform to any of the previously described criteria for confirmed cases.

The incidence rate was calculated based on the population estimated by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) during the study period. Statistical analyses were performed using the program Epi Info 3.5.1.

This study was approved by the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul Research Ethics Committee, under protocol no. 1147.

Results

During the 10 years of the study period, the average of pertussis incidence in Mato Grosso do Sul was 1.07 cases/100,000 population and the average of vaccine coverage was 81.48%. The vaccine used in Brazil is the whole-cell pertussis vaccine (WCVs).

Of the 561 pertussis suspected cases that were reported to the Health Department of the State of Mato Grosso do Sul – Brazil, 238 (42.4%) were confirmed and 281 (50.1%) were excluded. No classification was defined in the worksheet of 42 (7.5%) cases and these cases were not considered as confirmed or excluded.

Considering the confirmed cases, 132 (55.5%) were female and 106 (44.5%) were male. The highest incidence of cases (61.8%) occurred between zero to six months of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of vaccine doses by age group of pertussis cases, Mato Grosso do Sul – Brazil, from 1999 to 2008.

| Age group | N/% | Number of doses |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more | NR | ||

| Up to 2 m | 82/34.5 | 54 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 3–6 m | 65/27.3 | 15 | 21 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| 7–11 m | 10/4.2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 1–4 y | 33/13.9 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 11 | 6 |

| 5–9 y | 28/11.8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 5 |

| 10–14 y | 10/4.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| 15 y or more | 10/4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Total | 238/100 | 74/31.1 | 42/17.6 | 18/7.6 | 13/5.5 | 41/17.2 | 50/21 |

Note: m, months; y, years; NR, not reported.

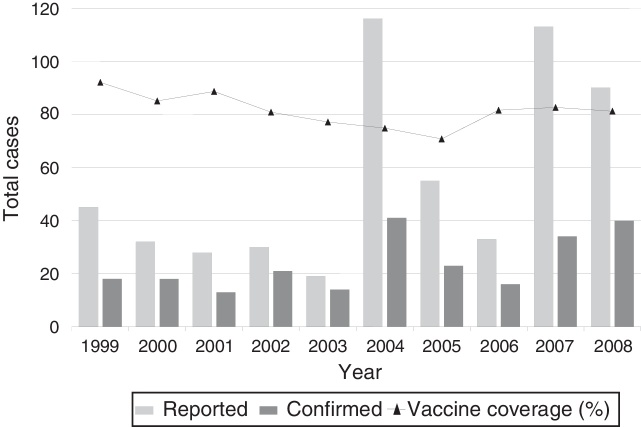

Among infected children, contagion occurred in 134 (56.3%) cases before the patient had reached the age recommended for the initiation of the vaccination scheme or showed incomplete immunization (up to two doses). Fig. 1 demonstrates the distribution of reported and confirmed pertussis cases during the study period and the percentage of vaccine coverage in the state.

Fig. 1.

Reported and confirmed pertussis cases and percentage of vaccine coverage, Mato Grosso do Sul, 1999–2008.

Regarding the diagnostic confirmation criteria, 7.6% (18/238) of the pertussis cases were confirmed by laboratory testing (positive culture), 22.7% (n = 54/238) by epidemiologic linkage (suggestive clinical profile and contact with confirmed case), 68.1% (162/238) by clinical criteria (suggestive clinical profile associated with leukocytosis and lymphocytosis) and the confirmation criteria was not included in the Pertussis Surveillance Worksheet of 1.7% (n = 4/238) cases. Nasopharyngeal secretion culture was collected of 61 confirmed cases patients and 18 (29.5%) of these cultures were positive.

Two pertussis outbreaks were observed in the state in 2004 and 2007. Fifty cases were reported during the first outbreak and 11 (22%) were confirmed while 68 cases were reported during the second outbreak and 12 (17%) cases were confirmed. No pertussis-related deaths occurred during the outbreaks.

Five deaths occurred among the confirmed cases and patients age ranged from 18 days to three years. The case fatality ratio over the whole 10-year period was 4.9% (4/82) in children up to two months and 0.9% (1/108) in children older than two months. Only one child was diagnosed by positive Bordetella pertussis culture; the others were confirmed by clinical criteria. The highest mortality rate of 11.11% was recorded in 2000. In the years 1999, 2002 and 2008, mortality rates were 5.56%, 4.46% and 2.56%, respectively.

Discussion

Bordetella pertussis infection remains a serious problem to children not immunized or with incomplete immunization. In Porto Alegre, 54% of children with pertussis had incomplete vaccination schedule with only 0–2 vaccine doses having been adminstered.7 The infection in these population suggests that adults who have lost their vaccinal immunity can be important sources of infection.3, 6

The higher incidence of pertussis in children up to six months has been also described by other Brazilian authors.7, 8 In Recife,8 72.5% of pertussis cases were found to occur in children younger than six months of age and in Porto Alegre 67.0% of children with pertussis were observed to be younger than one year.7

The USA pertussis incidence is lower than 1.0%. The high vaccination coverage in children by age two years has resulted in historically low levels of most vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. The estimated vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months ranged from 95.0% to 96.2% according to the National Immunization Survey of the United States, 2007–2011.9 In Europe, the vaccination coverage ranged from 90.0% in France to 100.0% in Sweden.10 On the other side, since 2012 United Kingdom faces outbreak of pertussis in unimmunized young children with high rates of morbidity and mortality.5

The majority of pertussis cases were identified by clinical criteria. These data are similar to another study in the country, where 51% of the cases were confirmed by clinical criteria, such as clinical profile (26%) and suggestive WBC.11

Culture is considered the gold standard for pertussis diagnosis and the only criteria for laboratory confirmation accepted by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.6, 12 Among different studies, positivity of cultures varied from 9.4% to 78%.4, 8 In our study, nasopharyngeal secretion was collected in just 25.6% (61/238). The culture of nasopharyngeal secretion was positive in 29.5% (18/61) of these cases, highlighting the difficulty in obtaining a definitive diagnosis. Culture sensitivity is influenced by several factors, including the fastidious nature of B. pertussis, the stage of the disease at which the collection was made, the vaccination status of the individual, the prior use of antibiotics and transport conditions of the samples.12

The geographical distance and the logistics of sending samples from the collection site to the laboratory where cultures were processed may also have interfered in the low percentage of positive results, since there was a single reference laboratory to perform all cultures in the state. Performing culture on all of the suspected cases and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technique PCR would also add to the identification of cases. Moreover, the state does not have a laboratory to perform the PCR for B. pertussis detection. PCR was adopted by many countries to aid in laboratory diagnosis and improve pertusssis surveillance.11, 13

The outbreaks observed in 2004 and 2007 occurred in the period in which children vaccination coverage was less than 90% in the State while Brazilian rates have remained at approximately 80% for children aged 1–12.14 The improvement of the epidemiological surveillance system may also explain the detection of the outbreaks.

Of the five reported deaths, similar to the result of other study, all of them occurred in children and the majority of them were younger than two months of age. The high morbidity as well as severity, increased risk of complications and mortality in children younger than six months are recognized factors involved in pertussis.15 The detection of pertussis over a period of 10 years and the evidence of two outbreaks demonstrate that disease is an important public health problem and there is an evident risk of infection to children under six months. It is also possible to have the suspected cases go underreported.

The difficulty of diagnosing pertussis by laboratory methods seems to collaborate to turn this into a neglected disease in the state. The implementation of new diagnostic methods, such as molecular biology techniques, could improve these results. In the same way, high vaccination coverage is certainly a good strategy to reduce the number of cases and to reduce the impact of the disease in children younger than six months.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank State Department of Health (SES-MS) for providing the data from System for Notifiable Diseases (SINAN) and the Central Laboratory for Public Health (LACEN-MS) for providing information about the cases.

References

- 1.Gabutti G., Rota M.C. Pertussis: a review of diseases epidemiology worldwide and in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:4626–4638. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9124626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (Geneva) Pertussis vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004;80:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sousa S.G., Barros H. Pertussis em Portugal – A importância de uma nova estratégia vacinal. Rev Port Pneumol. 2010;16:573–588. doi: 10.1016/s2173-5115(10)70060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisman D.N., Tang P., Hauck T., et al. Pertussis resurgence in Toronto, Canada: a population-based study including test-incidence feedback modeling. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:694. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amirthalingan G. Strategies to control pertussis in infats. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:552–555. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministério da Saúde (BR) 7th ed. SVS; Brasília: 2010. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Guia de Vigilância Epidemiológica. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevizan S., Coutinho S.E.D. Perfil epidemiológico da coqueluche no Rio Grande do Sul Brasil: estudo da correlação entre incidência e cobertura vacinal. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:93–102. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baptista P.N., Magalhaes V.S., Rodrigues L.C. Children with pertussis inform the investigation of other pertussis cases among contacts. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control Prevention national state local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months — United States 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:689–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Amersfoorth S.C.M., Schouls L.M., Van der Heide H.G.J., et al. Analysis of Bordetella pertussis populations in European countries with different vaccination policies. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2837–2843. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2837-2843.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministério da Saúde (BR) SVS; Brasília: 2005. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde: Núcleos hospitalares de epidemiologia: manual de implantação. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabella C. Pertussis: old foe, persistent problem. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72:601–608. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.72.7.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moraes J.C., Carvalhanas T., Bricks L.F. Should acellular pertussis vaccine be recommend to healthcare professionals? Cad Saude Publica. 2013;29:1277–1290. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2013000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormick C.M., Czachor J.S. Pertussis infections and vaccinations on Bolivia Brazil and Mexico form 1980 to 2009. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell H., Amirthalingam G., Andrews N., et al. Accelerating control of Pertussisin England and Wales. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:38–47. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]