Abstract

The aim of present study was to describe the frequency of lipodystrophy syndrome associated with HIV (LSHIV) and factors associated with dyslipidemia in Brazilian HIV infected children.

HIV infected children on antiretroviral treatment were evaluated (nutritional assessment, physical examination, and laboratory tests) in this cross-sectional study. Univariate analysis was performed using Mann–Whitney test or Fisher's exact test followed by logistic regression analysis. Presence of dyslipidemia (fasting cholesterol >200 mg/dl or triglycerides >130 mg/dl) was the dependent variable.

90 children were enrolled. The mean age was 10.6 years (3–16 years), and 52 (58%) were female. LSHIV was detected in 46 children (51%). Factors independently associated with dyslipidemia were: low intake of vegetables/fruits (OR = 3.47, 95%CI = 1.04–11.55), current use of lopinavir/ritonavir (OR = 2.91, 95%CI = 1.11–7.67). In conclusion, LSHIV was frequently observed; inadequate dietary intake of sugars and fats, as well as current use of lopinavir/ritonavir was associated with dyslipidemia.

Keywords: HIV, Lipodystrophy, Dyslipidemia, Children

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ARV) has changed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection from a near-uniformly fatal disease into a chronic, manageable illness. Before the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), 5–10% of infected children survived for more than three years after their serologic diagnosis. Presently, the mortality rate has decreased 70%.1 Children who survived HIV disease and AIDS are a new challenge to HIV/AIDS care standards, since this is the first generation of children who had the chance to use HAART.2 One important challenge are the adverse events associated with HAART, as they are described in adults as well as in children. The lipodystrophy syndrome (LSHIV), the redistribution of body fat (increased of centripetal fat – lipohypertrophy and/or reduction of peripheral fat – lipoatrophy) and/or metabolic changes related to lipids profile (dyslipidemia), and glucose intolerance, is one example of these adverse events.3, 4, 5 Another important issue is that HIV infected children and their caregivers must also deal with other challenges, related to the prevailing socioeconomic conditions in developing countries, such as nutrition deprivation, poor nutritional quality, or lack of regular physical activities.6

The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence of LSHIV and assess factors associated with dyslipidemia in HIV infected children treated with ARV, in a developing country setting, considering their nutrition routine.

Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional study conducted at the HIV clinic of Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira, a tertiary university pediatric hospital affiliated to the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (IPPMG–UFRJ), from October 2007 to January 2009. Children were included if they were two or more years old, HIV infected (confirmed by two different serological tests after 18 months of age), and on continuous ARV for at least the last three months prior to the interview.

Children were excluded if they had at the time of assessment any of the following: severe infection, opportunistic or bacterial infections, neoplastic disease, severe encephalopathy, wasting syndrome, or other metabolic disorders (such as diabetes and inborn errors of metabolism).

The LSHIV was defined as redistribution of body fat through peripheral lipoatrophy, centripetal lipohypertrophy or mixed form – presence of the two types of redistribution, and/or also the presence of laboratory abnormalities (dyslipidemia), based on the criteria defined by the European Pediatric Group lipodystrophy.4 Dyslipidemia was defined as serum cholesterol ≥200 mg/dl and serum triglyceride ≥130 mg/dl, after 12 h fasting. Data were collected during the interview and same pediatrician (LP) did all physical examinations. Height, weight, triceps, subscapular, and brachial skin folds, as well as waist circumference were measured. Waist and arm circumference were measured with ordinary tape measure. Sub-scapular and arm skin folds were measured with Langer adipometer, properly calibrated. All measures were taken three times, and a mean of them was used. Collected data were compared with the National Center for Health Statistics standard growth curve7 and transformed into z-scores using the formula: z-score = (observed value − mean)/standard deviation. Anthropometric data were compared with the tables suitable for age.8 Based on this anthropometric data, patients were classified as presenting peripheral lipoatrophy, centripetal lipohypertrophy or mixed form of LSHIV. Patients were classified according to Tanner curve, by the pediatrician (LP).

Laboratory data on fasting cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, CD4+ T lymphocytes and viral load were also collected. A food assessment survey was conducted assessing the 48-h food recall. Results were analyzed according to quality and quantity of each food group. It was considered inadequate if food intake was excessive and of poor quality and/or when it was below the recommended for each particular food group.9

Antiretroviral therapy (ARV), but the zidovudine syrup used for HIV vertical transmission prevention, was defined as the continuous use of any antiretroviral medication.

Food deprivation was considered when the patient was starving and did not have food access enough his/her for well-being for a week or more during their lives (excluding dietary recommendations).

The dependent variable was defined as the presence or absence of dyslipidemia in children. Independent variables were gender, age, age at HIV diagnosis, length of HAART use, CD4+ T lymphocytes percent cells, and viral load at the time of the interview. Socioeconomic status and nutritional variables were also evaluated: number of minimum Brazilian wages per capita, history of food deprivation (when the child had no food shortages due to poverty), inadequate intake (over or lack thereof) of food groups, treatment compliance (defined as self-report adherence to at least 95% of prescribed doses of ARV, three days prior the interview), physical activity (at least 30 min per day, at least three times a week of any physical activity).

Statistical analysis: the information obtained in the questionnaires were stored in a database using Access 2007® software. Subsequently, the distribution of all continuous variables was studied. The frequency of all the categorical variables was described and univariate analysis of continuous variables was performed using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney test if the variable did not have normal distribution. Univariate analysis of categorical variables was performed using the Fisher exact test followed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. The independent variables selected to be included in the final model were those that in univariate analysis presented with p-value <0.15. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package STATA version 9.0, Texas, USA.

Ethical considerations: this study was approved by IPPMG – Ethical Committee.

Results

Ninety patients were enrolled. The mean age was 127.3 months, and 52 children were female. Among the female group, 16 had history of menarche. The mean age of children when they were first diagnosed as HIV infected were 37 months.

Among the legal guardians of those children, 58 (64.4%) were illiterate or had less than eight years of education.

All children were using ARV for at least three months, 32 were in their first ARV regimen, 27 were in second ARV regimen, and 31 had experienced three or more ARV regimens. Protease inhibitor (PI) based regimen was the current ARV regimen of 47 children (43 on lopinavir/ritonavir), whereas 33 were on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) based regimens, and 10 patients were currently using nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) based regimens.

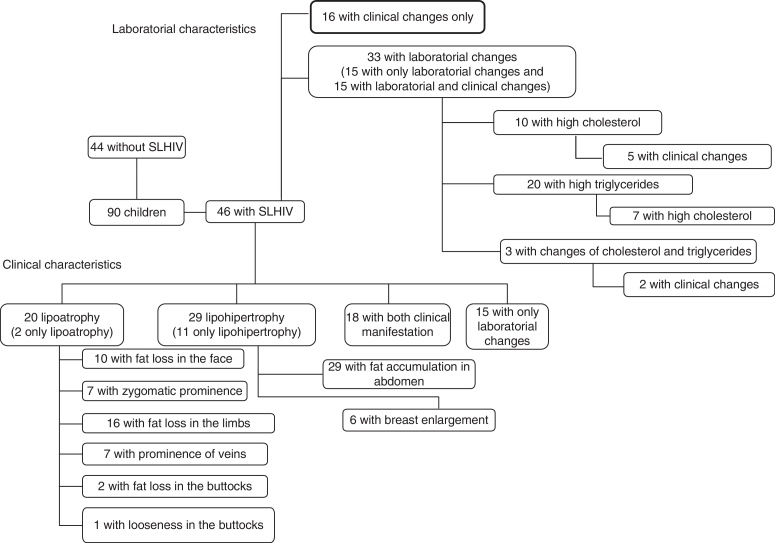

According to the European Pediatric Group lipodystrophy (4), 46 children presented lypodistrophy, as illustrated in Fig. 1. No children presented hyperglycemia. The mean cholesterol was 153.2 mg/dl and the mean triglyceride was 111.4 mg/dl.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of children according to clinical and laboratory characteristics of SLHIV.

Overall mean body mass index (BMI) was 16.6 (z-score −0.34), 17.1 for the group without LSHIV and 15.4 for the group with LSHIV (p = 0.01).

In Table 1 shows demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics according to the presence or absence of LSHIV Demographic characteristics (income), clinical presentation (category C event), laboratory data (nadir CD4+ lymphocytes), use of ARV (lopinavir/ritonavir), and nutritional history were associated with LSHIV.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the patients.

| Patients with LSHIVb (n = 46–51%) | Patients without LSHIV (n = 44–49%) | ORd | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender – female | 27/46 (59%) | 25/44 (57%) | 1.08 | 0.86 |

| HIV-vertically infected | 44/46 (96%) | 40/44 (91%) | 0.16 | 0.51 |

| Race – Caucasian | 16/46 (35%) | 11/44 (25%) | 0.62 | 0.31 |

| Admitted to the hospital in the last year | 10/46 (22%) | 4/44 (9%) | 2.77 | 0.10a |

| Regular physical activity | 11/46 (24%) | 10/44 (23%) | 1.06 | 0.89 |

| History of food deprivation | 13/46 (28%) | 9/44 (20%) | 1.53 | 0.39 |

| Income – per person (minimum Brazilian salary wages (mean) | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.04a | |

| Birth weight (mean – g) | 2586 | 2329 | 0.42 | |

| Age (at the interview), months (mean – months) | 121.8 | 133.1 | 0.19 | |

| Clinical classification C (CDC) | 23/46 (50%) | 15/44 (34%) | 1.93 | 0.07 |

| On any protease inhibitor | 27/46 (59%) | 20/44 (45%) | 1.71 | 0.21 |

| On LPV/rc | 27/46 (59%) | 16/44 (36%) | 2.49 | 0.03a |

| Time on the current ARV regimen (mean – months) | 25.5 | 28.7 | 0.53 | |

| 100% adherence, 3 days prior to the interview | 17/46 (37%) | 11/44 (25%) | 1.76 | 0.22 |

| Inadequate intake of sugars and fat | 23/46 (50%) | 10/44 (23%) | 3.40 | <0.01a |

| Inadequate intake of milk and dairy products | 16/46 (35%) | 10/44 (23%) | 1.81 | 0.21 |

| Inadequate intake of protein | 12/46 (26%) | 8/44 (18%) | 1.59 | 0.37 |

| Inadequate intake of vegetables/fruits | 40/46 (87%) | 29/44 (67%) | 3.40 | 0.02a |

| Inadequate intake of cereals | 9/46 (20%) | 4/44 (9%) | 2.43 | 0.18 |

| Nadir % CD4+ T cells (mean) | 15.17 | 19.70 | 0.06a | |

| Actual % CD4+ T cells (mean) | 25.67 | 25.93 | 0.81 | |

| Baseline viral load – log (mean) | 5.84 | 5.79 | 0.80 | |

| Current viral load – log (mean) | 4.47 | 3.74 | 0.19 | |

| Current ASTe – units/mL (mean) | 33 | 28 | 0.07a | |

| Current ALTf – units/mL (mean) | 20 | 18 | 0.54 |

Variables included in multivariate analysis.

LSHIV: lipodystrophy syndrome associated with HIV.

Lopinavir/ritonavir.

Odds ratio.

Aspartate aminotransferase.

Alanine aminotransferase.

CD4+ T lymphocytes varied from 45 to 2300 cells/mm3 (3–50%), and viral load at the moment of the interview varied from undetectable to 80,4000 copies/mL. All variables with p-value <0.15 were included in the multivariate analysis, except BMI. Table 2 shows the result of the multivariate analysis.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis – factors associated with LSHIV.a

| ORc | 95%CId | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income – per person (minimum Brazilian wage) salary wages (mean) | 0.96 | 0.77–1.21 | 0.74 |

| Nadir % CD4+ per cell | 0.96 | 0.92–1.00 | 0.08 |

| Inadequate intake of vegetables/fruits | 1.81 | 0.56–5.84 | 0.32 |

| Inadequate intake of sugars and fat | 3.05 | 1.10–8.46 | 0.03 |

| On LPV/rb | 2.51 | 0.94–6.75 | 0.06 |

| Admitted to the hospital in the last year | 1.87 | 0.45–7.74 | 0.39 |

| Current ASTe – per Unit/mL | 1.05 | 1.00–1.11 | 0.05 |

LSHIV: lipodystrophy syndrome associated with HIV.

Lopinavir/ritonavir.

Odds ratio.

95% confidence interval.

Aspartate aminotransferase.

Discussion

Among 90 children on ARV, 51% (46) were classified as having LSHIV; 22% presented lipoatrophy and 32% lipohypertrophy. The proportion of children affected by this syndrome ranged from 20 to 50%, according to studies that evaluated different populations.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In studies of adult groups, the prevalence of LSHIV varied from 15 to 50%.15 An European study of 426 children found a 42% prevalence of clinical manifestations of LSHIV.14 In a study involving 364 Ugandan children, the prevalence was lower: 27% presented clinical manifestations and 34% laboratory abnormalities. Glucose metabolism abnormalities were not observed.16 Werner et al. in a study of 30 Brazilian children on ARV, found 88.3% with dyslipidemia (laboratory abnormality) and only 13.9% with abnormal body fat distribution.17

Since all clinical diagnoses were prone to observer bias, i.e. even measuring circumferences and skin folds, the diagnosis of LSHIV is ultimately based on investigator impression, and hence we studied risk factors associated with dyslipidemia, considering nutritional history in our population.

Among the risk factors described in the literature, dyslipidemia was associated with older age, higher Tanner scores, and use of ARV (such as stavudine, lopinavir/ritonavir, and NNRTIs), white ethnicity, or higher viral load.11, 14, 16, 18, 19, 20 In our study, the risk factors independently associated with dyslipidemia were low intake of vegetables/fruits and current use of lopinavir/ritonavir.

Arpadi et al. observed significant associations between worse virological and immunological status at the baseline visit and the presence of changes consistent with LSHIV in a group of children.18 A study of the European Pediatric Group of Lipodystrophy demonstrated a significant relationship between children diagnosed as clinical category C (CDC) with lower CD4+ T lymphocytes and onset of changes consistent with LSHIV.4 A Thai pediatric study also described an association between the baseline C clinical category and LSHIV, but had not encountered any association with CD4+ T lymphocytes.21 In our study, we did not observe a relationship between dyslipidemia and immunosuppression, probably because this association is related with clinical manifestations of the LSHIV more than laboratory abnormalities. Flint et al. suggested that both treatment with antiretroviral drugs and some chronic inflammatory response to HIV stimulated the homeostatic response to stress at the cellular level, leading to adverse effects on the adipocytes metabolism. This process leads to a cycle of pathological lipotoxicity, lipoatrophy and, consequently, the phenotype of fat distribution with high waist–hip ratio, and of course the more severe HIV disease the child had, the worse the homeostatic response to stress at the cellular level they would present.22 Another important issue possibly associated with the inflammatory response was the positive association between aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and the presence of LSHIV. AST is a component of the AST platelet ratio index (APRI). This index (AST/platelets) is associated with liver fibrosis among HIV infected patients with and without other viral hepatitis23 patients, and a possible etiology for this fibrosis is the inflammatory disorder associated with HIV. The increased AST observed in the univariate analysis would also be a surrogate marker of fatty hepatic steatosis, more frequently described in obese children. However, if this was the case, the alanine aminotransferase should have also been elevated, which was not the case.24 Another hypothesis for this finding is that AST is increased due to the use of ARV; Ottop et al. studied 230 HIV infected adults in Cameroon, and patients who were on ARV had higher AST levels when compared with those without ARV.25

Although interventions to avoid and improve dyslipidemia were frequently based on improving the quality of diet,26 few studies evaluated the diet among LSHIV patients, and none in children, including children from developing countries.

The analysis of dietary survey was carried out according to specific food groups and was considered inadequate when above or below the recommended daily amount for the age-specific children. Individually, we observed that lower vegetables and sugar intake were significantly associated with LSHIV. These data support the hypothesis that, despite the absence of food deprivation, the quality of nutrition was far below the recommended levels. Such children with poor nutrition have greater chance of developing dyslipidemia. A review by Almeida et al., of 20 dietary intervention studies in adults, concluded that changes in lifestyle, diet and physical activity were always recommended as the first approach in the treatment of dyslipidemia, related or not to HIV, and our results corroborate this findings.27 In conclusion, any intervention to tackle dyslipidemia in children must aim at not only improving nutrition quality of the children, but also, whenever possible avoiding the use of ARV that would raise cholesterol or triglyceride levels, such as lopinavir/ritonavir.28

The design of this study was cross-sectional and aimed only to describe the presence of LSHIV and factors associated with dyslipidemia among children followed at the IPPMG's outpatient clinic. Some of the variables, such as the use of stavudine and lack of physical activity, although biologically plausible were not associated with dyslipidemia in our study, possibly due to the small sample size available.

We believe that longitudinal studies to investigate the role of diet on LSHIV prevention in this population must be pursued.

Funding

The study was supported by Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – Jovem Cientista do Nosso Estado – Cristina Barroso Hofer – 2008.

This work was carried out by the Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira with technical and financial support of the Ministry of Health/Secretariat of Health Surveillance/National STD and Aids Programme (MOH/SHS/NAP) through the Project of Cooperation AD/BRA/03/H34 between the Brazilian Government and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by IPPMG – Ethical Committee.

References

- 1.de Martino M., Tovo P.-A., Balducci M., et al. Reduction in mortality with availability of therapy for children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:190–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comulada W.S., Swendeman D.T., Rotheram-Borus M.J., Mattes K.M., Weiss R.E. Use of HAART among young people living with HIV. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27:389–400. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr A., Samaras K., Burton S., et al. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS. 1998;12:F51–F58. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Paediatric Lipodystrophy Group Antiretroviral therapy, fat redistribution and hyperlipidaemia in HIV-infected children in Europe. AIDS. 2004;18:1443–1451. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131334.38172.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montessori V., Press N., Harris M., Akagi L., Montaner J.S. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Can Med Assoc J. 2004;170:229–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buonora S., Nogueira S., Pone M.V., Aloé M., Oliveira R.H., Hofer C. Growth parameters in HIV-vertically-infected adolescents on antiretroviral therapy in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2008;28:59–64. doi: 10.1179/146532808X270699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000growthchart-us.pdf (accessed 04.10.12).

- 8.Vitolo M.R. first edition. Rubio Edition; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: 2008. Nutrição: da gestação ao envelhecimento. [Google Scholar]

- 9.http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/Fpyr/pmap.htm (accessed 04.10.12).

- 10.Sanchez Torres A.M., Munoz Muniz R., Madero R., Borque C., García-Miguel M.J., De José Gómez M.I. Prevalence of fat redistribution and metabolic disorders in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1610-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beregszaszi M., Dollfus C., Levine M., et al. Longitudinal evaluation and risk factors of lipodystrophy and associated metabolic changes in HIV-infected children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:161–168. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000178930.93033.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Europe-Paediatric-Lipodystrophy-Group Antiretroviral therapy, fat redistribution and hyperlipidaemia in HIV-infected children in Europe. AIDS. 2004;18:1443–1451. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131334.38172.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ene L., Goetghebuer T., Hainaut M., Peltier A., Toppet V., Levy J. Prevalence of lipodystrophy in HIV-infected children: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alam N., Cortina-Borja M., Goetghebuer T., Marczynska M., Vigano A., Thorne C. European Paediatric HIV and Lipodystrophy Study Group in EuroCoord Body fat abnormality in HIV-infected children and adolescents living in Europe: prevalence and risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:314–324. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824330cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J., Carr A., Emery S., et al. HIV lipodystrophy: prevalence, severity and correlates of risk in Australia. HIV Med. 2003;4:293–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piloya T., Bakeera-Kitaka S., Kekitiinwa A., Kamya M.R. Lipodystrophy among HIV-infected children and adolescents on highly active antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: a cross sectional study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15 doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner M.L., Pone M.V., Fonseca V.M., Chaves C.R. Lipodystrophy syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents infected with HIV/AIDS receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010;86:27–32. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arpadi S.M., Cuff P.A., Horlick M., Wang J., Kotler D.P. Lipodystrophy in HIV-infected children is associated with high viral load and low CD4+-lymphocyte count and CD4+-lymphocyte percentage at baseline and use of protease inhibitors and stavudine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:30–34. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200105010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallego-Escuredo J.M., Del Mar Gutierrez M., Diaz-Delfin J., et al. Differential effects of efavirenz and lopinavir/ritonavir on human adipocyte differentiation, gene expression and release of adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Curr HIV Res. 2010;8:545–553. doi: 10.2174/157016210793499222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giralt M., Díaz-Delfín J., Gallego-Escuredo J.M., Villarroya J., Domingo P., Villarroya F. Lipotoxicity on the basis of metabolic syndrome and lipodystrophy in HIV-1-infected patients under antiretroviral treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3371–3378. doi: 10.2174/138161210793563527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aurpibul L., Puthanakit T., Lee B., Mangklabruks A., Sirisanthana T., Sirisanthana V. Lipodystrophy and metabolic changes in HIV-infected children on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:1247–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flint O.P., Noor M.A., Hruz P.W., et al. The role of protease inhibitors in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated lipodystrophy: cellular mechanisms and clinical implications. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37:65–77. doi: 10.1177/0192623308327119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price J.C., Seaberg E.C., Badri S., Witt M.D., D’Acunto K., Thio C.L. HIV monoinfection is associated with increased aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, a surrogate marker for hepatic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1005–1013. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiegand S., Keller K.M., Röbl M., et al. APV-Study Group and the German Competence Network Adipositas. Obese boys at increased risk for nonalcoholic liver disease: evaluation of 16,390 overweight or obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1468–1474. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.106. [Epub 2010 June 8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottop F.M., Atashili J., Ndumbe P.M. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on glycemia and transaminase levels in patients living with HIV/AIDS in Limbe, Cameroon. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012 doi: 10.1177/1545109712447199. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter R.J., Wiener J., Abrams E.J., et al. Perinatal AIDS Collaborative Transmission Study-HIV Follow-up after Perinatal Exposure (PACTS-HOPE) Group. Dyslipidemia among perinatally HIV-infected children enrolled in the PACTS-HOPE cohort, 1999–2004: a longitudinal analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:453–460. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000218344.88304.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almeida L.B., Giudici K.V., Jaime P.C. Dietary intake and dyslipidemia arising from combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2009;53:519–527. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302009000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn L., Coovadia A., Strehlau R., et al. Switching children previously exposed to nevirapine to nevirapine-based treatment after initial suppression with a protease-inhibitor-based regimen: long-term follow-up of a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:521–530. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]