Abstract

Background

Human parainfluenza viruses account for a significant proportion of lower respiratory tract infections in children.

Objective

To assess the prevalence of Human parainfluenza viruses as a cause of acute respiratory infection and to compare clinical data for this infection against those of the human respiratory syncytial virus.

Methods

A prospective study in children younger than five years with acute respiratory infection was conducted. Detection of respiratory viruses in nasopharyngeal aspirate samples was performed using the indirect immunofluorescence reaction. Length of hospital stay, age, clinical history and physical exam, clinical diagnoses, and evolution (admission to Intensive Care Unit or general ward, discharge or death) were assessed. Past personal (premature birth and cardiopathy) as well as family (smoking and atopy) medical factors were also assessed.

Results

A total of 585 patients were included with a median age of 7.9 months and median hospital stay of six days. No difference between the HRSV+ and HPIV+ groups was found in terms of age, gender or length of hospital stay. The HRSV+ group had more fever and cough. Need for admission to the Intensive Care Unit was similar for both groups but more deaths were recorded in the HPIV+ group. The occurrence of parainfluenza peaked during the autumn in the first two years of the study.

Conclusion

Parainfluenza was responsible for significant morbidity, proving to be the second-most prevalent viral agent in this population after respiratory syncytial virus. No difference in clinical presentation was found between the two groups, but mortality was higher in the HPIV+ group.

Keywords: Parainfluenza, Paramyxoviridae infections, Respiratory tract infections, Respiratory virus

Introduction

Acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) in childhood are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, with pneumonia being the leading cause of death among children between one and five years old.1, 2 Viruses are the predominant etiology of ARTIs in this pediatric group.3, 4, 5

The human parainfluenza viruses (HPIVs) account for a significant proportion of lower respiratory tract infections in children, where their rates of detection vary with pathology (respiratory infection of the upper or lower tract) and with the investigation setting (outpatient units or hospital wards).6

With the attention of parents and medical professionals firmly focused on annual outbreaks of respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) and influenza, HPIV infections can be overlooked.7 However, HPIVs are the second most common cause of lower and upper respiratory tract infections in children younger than five years after HRSV.8, 9, 10, 11

This prospective study was conducted to determine the prevalence of HPIVs in children hospitalized for ARTI, assess the clinical characteristics of HPIV+ and HRSV+ patients, and to compare the two groups identifying any specific features of infections caused by HPIVs. Seasonality was also examined in the present study.

Methods

This prospective study included all children with ARTI younger than five years with prodromes of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) on clinical history, admitted to the hospital general wards or Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of the Department of Pediatrics of Santa Casa de São Paulo Hospital (São Paulo city), between February 2005 and May 2007. After 2007, surveillance continued but using other methodology for diagnosing viral infections. Immunosuppressed patients like HIV-infected, and those with neoplasia or transplantions were excluded.

The Central Hospital at Santa Casa de São Paulo is a reference university hospital for the central and northern region of the city providing high complexity care, including emergency care. Approximately 60,000 patients receive medical attention annually at urgency and emergency units. Out of 9500 admissions during the study period, around one-third was due to respiratory infections. Data on clinical characteristics and demographics were collected at patient admission. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital under the number 064/09. Prior to inclusion in the study, parents or legal guardians of the patients signed a free and informed consent form. ARTI was defined as the presence of two or more signs of inferior respiratory tract involvement: respiratory dysfunction, characterized by fatigue, tachypnea, wheezing, crackling, and/or fever (axillar temperature of 37.8 °C) on physical exam. The prodromes of URTIs were characterized by the presence of coryza, sneezing, and/or nasal obstruction. Disease history was considered in the last five days. Bronchiolitis was characterized by first episodes of wheezing in infants with URTI prodromes; children with previous episodes of pulmonary wheezing were diagnosed as recurrent wheezing, while acute crisis was characterized as acute wheezing. Cases with crackles on pulmonary auscultation and lung consolidation on chest radiography exams were considered alveolar pneumonia, whereas cases with diffuse infiltration and with crackling on pulmonary auscultation were diagnosed as non-alveolar pneumonia.

All patients included in the study had samples of nasopharyngeal secretion collected within the first 24 h of admission. Samples were then stored on ice and sent to the Adolfo Lutz institute for Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF), performed using a panel of five monoclonal antibodies specific for HRSV, Influenza A and B, HPIV 1, 2 and 3, and Adenovirus, for the detection of seven viruses (Kit Light Diagnostic TM, Chemicon International Inc, Temecula, USA).

Variables analyzed included age, gender, admission date, clinical characteristics (cough, fever, shortness of breath, and apnea), data on physical exam (wheezing, dyspnea, cyanosis, inspiratory nasal wing collapse), clinical diagnoses, personal (cardiopathy, premature birth, and gastroesophagic reflux) and family (smoking and atopy) medical histories, patient hospital ward (general or ICU), and outcome (discharge or death).

Patients were categorized into two groups (HPIV+ or HRSV+ on IIF) and subsequently compared. Medians of quantitative variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Qualitative variables were analyzed by comparing proportions in each group using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests as applicable. The level of significance was set at 0.05. All statistical tests were performed using the Sigma Stat program version 3.5.

Results

A total of 585 patients were included in the study. HPIVs were detected in 45 patients, corresponding to 19.9% of all positive cases, and 7.7% of children overall. The HRSV was the most frequently detected viral agent (26.5%). IIF was positive for influenza in 3.42% of patients and adenovirus in 1%. The clinical data of the HPIV-positive patients was compared against data from HRSV-positive subjects (see Table 1). A total of 44.4% of HPIV positive patients were female versus 43.9% in the HRSV-positive group. Median age was similar among HPIV+ and HRSV groups, 6.8 and 7.1 months, respectively. Length of hospital stay (median six days) was also similar in the two groups. Comparing signs and symptoms of acute lower respiratory tract infection between HPIV+ and HRSV+ groups revealed greater proportion of cough (96.1% vs 82.2%, p < 0.05) and fever (72.3% vs 48.9%, p < 0.05) in the HRSV group. No statistically significant difference was found for the other signs and symptoms examined, including shortness of breath, wheezing, dyspnea, and cyanosis. The most frequent diagnoses in the HPIV+ group were acute wheezing (28.9%), non-alveolar pneumonia associated to acute wheezing (26.7%), and bronchiolitis (22.2%). In the HRSV+ group diagnoses were bronchiolitis (35.5%), non-alveolar pneumonia associated with acute wheezing (27.1%), and acute wheezing (14.5%). Both groups were similar with regard to past personal medical history of premature birth, congenital cardiopathy, and gastroesophagic reflux disease, as well as for family history of atopy and smoking (Table 1). Of the patients in the HRSV+ group, 10.9% were ICU cases compared with 15.5% in the HPIV+ group (Table 1). A greater number of deaths were recorded in the HPIV+ group compared with the HRSV+ group (8.9% vs. 1.29%, p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics associated with infections by human parainfluenza viruses (HPIVs) and respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) (n = 585).

| Clinical characteristics | PIVs (n = 45) |

HRSV (n = 155) |

|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 20 (44.4%) | 68 (43.9%) |

| Median age (months) | 6.8 | 7.1 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 6 | 6 |

| Signs and symptoms of ARTI | ||

| Cough | 37 (82.2%) | 149 (96.1%)a |

| Fever | 22 (48.9%) | 112 (72.3%)b |

| Shortness of breath | 28 (62.2%) | 115 (74.2%) |

| Wheezing | 30 (66.7%) | 85 (54.8%) |

| Dyspnea | 27 (60%) | 96 (61.9%) |

| Cyanosis | 4 (8.9%) | 4 (2.58%) |

| ARTI diagnoses | ||

| Acute wheezing | 13 (28.9%) | 23 (14.5%) |

| Non-alveolar pneumonia | 12 (26.7%) | 42 (27.1%) |

| Bronchiolitis | 10 (22.2%) | 55 (35.5%) |

| Personal medical history | ||

| Premature birth | 6 (13.3%) | 13 (8.4%) |

| Congenital cardiopathy | 4 (8.9%) | 8 (5.2%) |

| Gastroesophagic reflux | 5 (11.1%) | 11 (7.1%) |

| Family medical history | ||

| Atopy | 20 (44.4%) | 56 (36.1%) |

| Smoking | 6 (13.3%) | 20 (12.9%) |

| ICU admission | 7 (15.5%) | 17 (10.9%) |

| Death | 4 (8.9%) | 2 (1.3%)c |

p = 0.0037.

p = 0.0058.

p = 0.024.

Of the HPIVs detected, the most frequent type was HPIV-3 (84.4%) followed by HPIV-2 (8.89%) and HPIV-1 (6.67%).

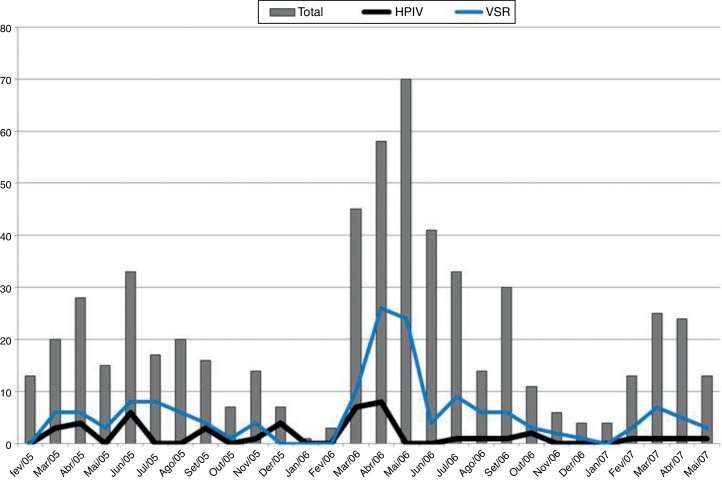

The peak detection rate of the HRSV occurred in the autumn season during the study period. In the first two years of the study, a higher incidence of HPIVs was observed accompanying the HRSV peaks (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of cases by month and number of patients with human parainfluenza viruses (HPIV) or with human respiratory syncytial virus (VSR).

Discussion

The HPIVs are important etiologic agents of acute respiratory infection in childhood and rank second among the most common diseases in this age group by some authors. HPIVs predominantly cause lower respiratory tract infection in infants and young children,12, 13, 14 and the significance of the virus has been underappreciated.9

In the present investigation, the prevalence of HPIVs was 7.7%, the second most common virus after HRSV, whose prevalence was 26.5%. This result corroborates the findings of other studies with similar design.15, 16, 17 We adopted IIF as the method of viral investigation, as it is a reliable technique with 50–75% sensitivity and excellent specificity.12, 18 Some authors claim that molecular methods (PCR and Real-Time PCR) offer 10–20% greater sensitivity for detecting HPIVs over culture and IIF techniques,19, 20 but with higher cost.

Earlier studies have reported higher prevalence of HPIVs than in the present study but had different study designs and viral detection methods. For instance, the study by Rihkanen et al., investigating the etiology of croup in patients attending emergency services, found HPIVs, particularly type 1, in 29.1% of patients.21 HPIV1 is known to be the main etiologic agent of croup, accounting for 56–74% of such cases. A cohort study conducted in Spain, involving patients hospitalized for ARTI aged up to 14 years using PCR as the viral detection method, showed a 9.9% HPIV prevalence, ranking third among the most frequent viruses after the HRSV, Rhinovirus and Adenovirus.6 In a study aiming to determine the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients aged younger than five in Salvador city in northeastern Brazil, HPIVs ranked second among the most prevalent agents, followed by Rhinovirus.22

The prevalence of HPIV-3 was substantially higher than HPIV-1 and 2 in this study, whereas HPIV-4 was not studied. It is known that HPIV-3 is the HPIV type most frequently detected in hospitalized patients, particularly among young infants, and associated with the diagnoses of bronchiolitis and pneumonia.12, 23

Other studies have shown HPIV-3 to be the most prevalent in hospitalized patients, such as the work by Calvo et al.6 in addition to studies conducted in Brazil by Fe et al.24 assessing the prevalence of HPIVs in patients up to 16 years old with ARTI, and the study by Veja-Briceño et al. conducted in Chile.25 Evidence confirms that HPIV-1 is associated with the diagnosis of croup, but not a single case of croup or laryngitis associated to croup was found in our study, perhaps because our cases were often less severe, not requiring hospitalization.

Comparing the clinical data of HPIVs and HRSV infected groups, we found no statistically significant differences in terms of hospital stay or need for ICU admission. With regard to signs and symptoms of ARTI, there were greater proportions of cough and fever in the HRSV-infected group. Despite this association, because signs and symptoms were very unspecific and general, none of these could be attributed to a specific agent.25, 26

The highest rates of HPIV isolation (detection) occurred during autumn in the first two years of the study, coinciding with peak incidence of the HRSV. The classic seasonal pattern of HPIV infection is described in the United States, with biannual peaks of HPIV1 during fall and winter, and annual peaks of HPIV3, particularly at the end of winter or in spring.9, 27 Studies in tropical countries are scarce, although one investigation reported seasonal peaks of HPIV3 at the end of winter and in spring in Rio de Janeiro,28 while other studies carried out in Northeastern and Southern Brazil both showed peaks during October, coinciding with spring.24, 29

Evidence shows that HPIV infections tend to be less severe than those caused by HRSV.6 More deaths occurred in children hospitalized for HPIVs than among HRSV-infected patients. The deaths occurred in children outside the age group at higher risk for developing severe disease (less than three months old), but all these cases had contributing medical factors, with two having history of premature birth, one recurrent wheezing case with gastroesophagic reflux, and another with delayed neuro-psychomotor development secondary to neonatal anoxia and recurrent wheezing. The prevention strategy of administering immunoglobulin is well established for HRSV, and studies are underway for vaccines against this agent. For HPIVs however, viruses with significant impact in terms of morbidity and mortality, no established strategy is currently in place.

In conclusion, the impact caused by HPIVs infections is significant in hospitalized children, where this agent should be considered as a cause of ARTI. Longitudinal studies determining the prevalence of respiratory viruses should be encouraged to help devise prevention and treatment strategies.

Funding

This study was funded by FAPESP – Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Approval Number in Internal Review Board (Research Ethical Committee) – 064/09.

References

- 1.UNICEF. World Health Organization (WHO) UNICEF/WHO; Geneva: 2006. Pneumonia: the forgotten Killer of children. 40 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams B.G., Gouws E., Boschi-Pinto C., Bryce J., Dye C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet infect Dis. 2002;2:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lourenção L.G., Júnior J.B.S., Rahal P., Souza F.P., Zanetta D.M.T. Infecção pelo Vírus Sincicial Respiratório em Crianças. Pulmão RJ. 2005;14:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilger D.A., Cantarelli V.V., Amantea S.L., et al. Detection of human bocavirus and human metapneumovirus by real-time PCR from patients with respiratory symptoms in Southern Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106:56–60. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonzel L., Tenenbaum T., Schroten H., Schildgen O., Schweitzer-Krantz S., Adams O. Frequent detection of viral coinfection in children hospitalized with acute respiratory tract infection using a real-time polymerase chain reaction. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:589–594. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181694fb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo C., Garcia-Garcia M.L., Ambrona P., et al. The burden of infections by parainfluenza virus in hospitalized children in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:792–794. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318212ea50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu S.S., Chan K.H., Chen H., et al. Virologically confirmed population-based burden of hospitalization caused by respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, and parainfluenza viruses in children in Hong Kong. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:1088–1092. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e9de24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H.T., Jiang Q., Zhou X., et al. Identification of a natural human serotype 3 parainfluenza virus. Virol J. 2011;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinberg G.A. Parainfluenza viruses: an underappreciated cause of pediatric respiratory morbidity. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:447–448. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000218037.83110.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee M.S., Mendelman P.M., Sangli C., Cho I., Mathie S.L., August M.J. Half-life of human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) maternal antibody and cumulative proportion of HPIV3 infection in young infants. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1281–1284. doi: 10.1086/319690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf D.G., Greenberg D., Kalkstein D., et al. Comparison of human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A virus lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:320–324. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000207395.80657.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrickson K.J. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:242–264. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.242-264.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato M., Wright P.F. Current status of vaccines for parainfluenza virus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:S123–S125. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318168b76f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teo W.Y., Rajadurai V.S., Sriram B. Morbidity of parainfluenza 3 outbreak in preterm infants in a neonatal unit. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:837–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwane M.K., Edwards K.M., Szilagyi P.G., et al. Population-based surveillance for hospitalizations associated with respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza viruses among young children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1758–1764. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noyola D.E., Arteaga-Dominguez G. Contribution of respiratory syncytial virus, influenza and parainfluenza viruses to acute respiratory infections in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:1049–1052. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000190026.58557.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pecchini R., Berezin E.N., Felicio M.C., et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of the infection by the respiratory syncytial virus in children admitted in Santa Casa de Sao Paulo Hospital. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:476–479. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702008000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenhow T.L., Weintrub P.S. Utility of direct fluorescent antibody testing of nasopharyngeal washes in children with and without respiratory tract illness. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:502–506. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000222401.21284.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freymuth F., Vabret A., Cuvillon-Nimal D., et al. Comparison of multiplex PCR assays and conventional techniques for the diagnostic of respiratory virus infections in children admitted to hospital with an acute respiratory illness. J Med Virol. 2006;78:1498–1504. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syrmis M.W., Whiley D.M., Thomas M., et al. A sensitive, specific, and cost-effective multiplex reverse transcriptase-PCR assay for the detection of seven common respiratory viruses in respiratory samples. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:125–131. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60500-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peltola V., Heikkinen T., Ruuskanen O. Clinical courses of croup caused by influenza and parainfluenza viruses. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:76–78. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nascimento-Carvalho C.M., Ribeiro C.T., Cardoso M.R., et al. The role of respiratory viral infections among children hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia in a developing country. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:939–941. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181723751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez M., Mufson M.A., Dubovsky F., Knightly C., Zeng W., Losonsky G. Phase-I study MEDI-534, of a live, attenuated intranasal vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza-3 virus in seropositive children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:655–658. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318199c3b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fe M.M., Monteiro A.J., Moura F.E. Parainfluenza virus infections in a tropical city: clinical and epidemiological aspects. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:192–197. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702008000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vega-Briceno L.E., Pulgar B.D., Potin S.M., Ferres G.M., Sánchez D.I. Clinical and epidemiological manifestations of parainfluenza infection in hospitalized children. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2007;24:377–383. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182007000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomazelli L.M., Vieira S., Leal A.L., et al. Surveillance of eight respiratory viruses in clinical samples of pediatric patients in southeast Brazil. J Pediatr. 2007;83:422–428. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall C.B. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1917–1928. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nascimento J.P., Siqueira M.M., Sutmoller F., et al. Longitudinal study of acute respiratory diseases in Rio de Janeiro: occurrence of respiratory viruses during four consecutive years. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1991;33:287–296. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651991000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straliotto S.M., Siqueira M.M., Muller R.L., Fischer G.B., Cunha M.L., Nestor S.M. Viral etiology of acute respiratory infections among children in Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35:283–291. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822002000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]