Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of licorice in H. pylori eradication in patients suffering from dyspepsia either with peptic ulcer disease (PUD) or non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) in comparison to the clarithromycin-based standard triple regimen.

Methods

In this randomized controlled clinical trial, 120 patients who had positive rapid urease test were included and assigned to two treatment groups: control group that received a clarithromycin-based triple regimen, and study group that received licorice in addition to the clarithromycin-based regimen for two weeks. H. pylori eradication was assessed six weeks after therapy. Data was analyzed by chi-square and t-test with SPSS 16 software.

Results

Mean ages and SD were 38.8 ± 10.9 and 40.1 ± 10.4 for the study and control groups, respectively, statistically similar. Peptic ulcer was found in 30% of both groups. Response to treatment was 83.3% and 62.5% in the study and control groups, respectively. This difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion

Addition of licorice to the triple clarithromycin-based regimen increases H. pylori eradication, especially in the presence of peptic ulcer disease.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Licorice, Dyspepsia, Peptic ulcer

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram negative S shaped flagellated bacteria infecting half of mankind with a very variable prevalence depending on different factors such as race, age, and socioeconomic status ranging from a low prevalence in developed countries to a prevalence as high as 80% in developing countries like Iran.1 H. pylori is a successful pathogen which can persistently survive in the stomach of infected persons throughout his/her life and if it results in chronic inflammation serious digestive diseases may ensue such as chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastric cancer, and gastric MALT-oma (mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma).2

Peptic ulcer disease is one of the consequences of H. pylori infection and is one of the most common treatable diseases worldwide. The commonest cause of peptic ulcer is H. pylori and if not eradicated it will result in 50–80% relapse in 6–12 months after treatment interruption,3 but if successfully treated its recurrence will drop to 6–20%, as reported by two separate meta-analyses.4, 5

Relation between dyspepsia and H. pylori is unclear, but eradication leads to symptoms improvement in 7.1% of patients.6

American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends the treatment of H. pylori in all infected patients irrespective of the presence of ulcer. Recommended first line standard regimen by ACG for the treating H. pylori is a triple regimen containing clarithromycin, amoxicillin or metronidazole, and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for 10–14 days. Quadruple regimen is recommended in areas where the prevalence and resistance to clarithromycin or metronidazole is more than 20%, or if the first choice has been tried recently or repeatedly.7

Antibiotic resistance to H. pylori has increased in recent past years. Compared to 2010 the resistance rate to clarithromycin and amoxicillin in 2012 has raised significantly.8 The effectiveness of the present therapeutic regimen is still not satisfactory and despite several studies the best treatment regimen for treating H. pylori remains a challenging clinical dilemma.9 Antibiotic resistance and adverse effects in addition to poor patient compliance have limited the efficacy of H. pylori treatment. Therefore, the role of herbal medicine has been evaluated in the treatment of H. pylori, including licorice (liquorice).10

Licorice herb (Glycyrrhiza glabra - G. glabra) has routinely been used for centuries in traditional Chinese.11 Roots and rhizomes of this herb has been reported to be antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antiviral.12, 13 Furthermore, G. glabra has anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and anti-ulcer activity.14, 15, 16 Licorice is extracted from the root of G. glabra herb and one of its active ingredient is glycyrrhizin acid, which due to its affinity to mineralocorticoid receptors may result in edema and hypertension. Therefore, it should be used with caution in patients suffering from cardiovascular disease and/or hypertension.17 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Photograph of Glycyrrhiza glabra herb.

There two types of action of licorice in PUD and against H. pylori: (1) a repairing effect in PUD: protective mucosal effect by secreting a material named as secretin18; and (2) antibacterial and anti-adhesive effect against H. pylori by inhibiting DNA gyrase (a crucial enzyme for bacterial replication and transcription) and dihydrofolate reductase enzyme blockage.19 In addition, the polysaccharide released from the root of licorice plays an inhibiting role in H. pylori adhesion to gastric mucosa.20 Besides, treatment with licorice for patients suffering from dyspepsia improves their clinical complaints.21

Owing to the rise of H. pylori resistance against antibiotics and the effectiveness of licorice for treating H. pylori, this study was designed to compare the efficacy of adding licorice to the standard clarithromycin-based triple regimen in the treatment of H. pylori.

Material and methods

This randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted in Velayat teaching hospital in Qazvin (northwest of Iran). A total of 120 patients over 16 years of age referred for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) at the digestive disease outpatient department due to gastrointestinal complains entered this study from May to December of 2015. Biopsy was performed when indicated by the endoscopist.

Patients with a positive rapid urease test were included in this study if none of the following conditions were present: pregnancy, use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI), bismuth or antibiotic in the past two weeks, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding or any complication of PUD, giant ulcer, gastric ulcer, ethanol consumption or substance abuse, chronic underlying disease like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cirrhosis, cerebrovascular attack, coronary artery disease, and gastric cancer. Patients who were reluctant to continue the treatment or complete the follow-up or suffering from a comorbidity needing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or antibiotic to be continued during the period of study were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all eligible. Sixty patients were randomly assigned to receive one of two treatment regimens: triple regimen consisting of clarithromycin (500 mg BID) + Amoxicillin (1 gr qd) + 20 mg BID of Omeprazole (control group) or the same regimen supplemented by licorice [D-Reglis (380 mg BID) made by Iran daruc Pharmacy Company] for two weeks (LR group). Both groups received at least four weeks of treatment with omeprazole 20 mg daily subsequently. Two weeks after completing the treatment, H. pylori eradication was assessed with H. pylori stool antigen (HPSA) test by Ag ACON Biotech (Hang Zhou) Co., Ltd.

This study is registered at Iran Registration Clinical Trial Center and was approved with the Irct registration number: IRCT2014061718124N1.

The outcome of this study was H. pylori eradication. Data were stored at SPSS 16 software and analyzed by using of t-test, chi-square test. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

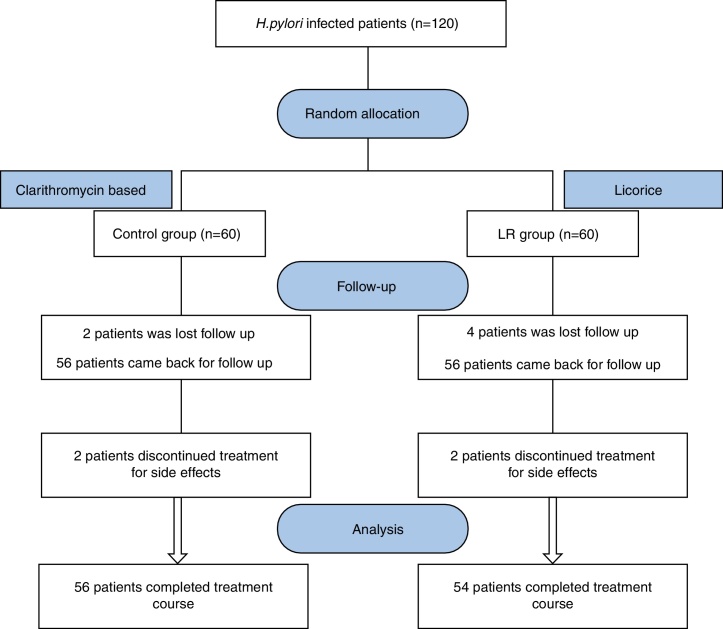

Out of 120 eligible patients, 110 patients completed the study complying with the prescribed medications and follow-up; 54 patients were assigned to the licorice group (LR) and 54 patients to the control group (schematic presentation of study groups is illustrated in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study flow chart (Control Group: Clarithromycin +Amoxicillin + Omeprazole regimen, Licorice (LR) Group: Licorice + Clarithromycin +Amoxicillin + Omeprazole).

Demographic variables of both treatment groups were similar. Mean ages were 38.8 and 40.1 years for the LR and control groups, respectively (p = 0.56); 35 patients (51.0%) of LR group and 33 persons (48.1%) of the control group were female (p > 0.05). Patients in two groups were also similar regarding to their clinical characteristics (initial complaints and endoscopic findings). Frequency distribution of their clinical characteristics is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of licorice (LR) and control groups.

| Group Clinical characteristics |

LR group (N:60) | Control group (N:60) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Abdominal pain | 37 (61.7%) | 42(70%) | 0.442 |

| Early satisfied | 8(13.3%) | 5(8.3%) | 0.558 |

| Bloating | 12(20.0%) | 15(25%) | 0.662 |

| Heart burn | 13(21.7%) | 15(25%) | 0.829 |

| Nausea | 2(3.3%) | 4(6.7%) | 0.679 |

| Endoscopic finding | |||

| Duodenal ulcer | 21(35.0%) | 18(30.0%) | 0.697 |

| Antral erythema | 29(48.3%) | 32(55.3%) | 0.715 |

| Antral nodularity | 7(11.7%) | 5(8.3%) | 0.762 |

| Duodenal erythema | 4(6.7%) | 2(3.3%) | 0.679 |

| No pathologic finding | 7(11.7%) | 8(13.3%) | 1.000 |

Furthermore, both groups had similar rates of endoscopic diagnosis of PUD or non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD): 21 (35%) and 18 patients (30%) in the LR and control groups, respectively, had PUD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Endoscopic diagnosis of licorice (LR) and control groups.

| Endoscopic diagnosis | Peptic ulcer | Non-ulcer dyspepsia | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR group (N:60) | 21 (35.0%) | 39 (65.0%) | 60 (100.0%) | 0.697 |

| Control group (N:60) | 18 (30%) | 42 (70.0%) | 60 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 39 (32.5%) | 81 (67.5%) | 120 (100.0%) |

HPSA negative, the surrogate for H. pylori eradication and positive therapeutic response, was 83.3% in the LR group compared to 62.5% in the control group (p = 0.018). Response rate based on endoscopic findings was significantly higher for the LR group to treat PUD, but not for NUD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of response to treatment (negative HPSA) in the LR and control groups.

|

aHPSA Endoscopic diagnosis |

LR group (N:54) |

Total | Control group (N:56) |

Total | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative N (%) | Positive N (%) |

N (%) | Negative N (%) | Positive N (%) |

N (%) | ||

| Non-ulcer dyspepsia | 28 (82.4%) | 6 (17.6%) | 34 (100%) | 27 (67.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | 40 (100%) | 0.186 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 17 (85.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 20 (100%) | 8 (50%) | 8 (50%) | 16 (100%) | 0.034b |

| Total | 45 (83.3%) | 9 (16.7%) | 54 (100%) | 35 (62.5%) | 21 (37.5%) | 56 (100%) | 0.018b |

Helicobacter pylori stool antigen.

Significant level was >0.05.

Discussion

This study was conducted with the aim of evaluating the effectiveness of licorice in H. pylori eradication of patients suffering from dyspepsia (both PUD and NUD) compared to the clarithromycin-based standard triple regimen. Results of this study showed that adding a low dose licorice (D-Reglis 380 mg BID) to the standard triple treatment results in a more effective H. pylori eradication, especially in patients with PUD. During the recent past decades many studies on H. pylori infection have been conducted to define the adequate therapy. As H. pylori is considered a major risk factor for upper digestive problems guidelines often recommend treating all infected persons irrespective of the clinical presentation. Besides the clinical impact, H. pylori eradication would also prevent its spread.22

In the present study the addition of licorice increased the effectiveness of H. pylori eradication compared to standard clarithromycin-based triple regimen, a finding similar to previous in vitro studies.20, 23

Toshio Fukai investigated the anti-H. pylori in vitro effect of various preparations of licorice and showed that the leaves and rhizomes of this herb prevented the multiplication of H. pylori. In addition, he also proved that licorice had anti-H. pylori effect against the species resistant to clarithromycin.24

Asha MK reported that G. glabra has antimicrobial effect against several Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria including H. pylori. Additionally, licorice is also beneficial against H. pylori due to its anti-adhesive property.25

Dosage of licorice has varied in few clinical studies, such as in a study by Sreenivasulu Parum et al. in which a dose of 120 mg/day was used for H. pylori eradication in patients with dyspepsia,21 or a dose of 250 mg TID in PUD with H. pylori infection in a study by Rahnama et al.,26 or a tablet of D-Reglis 380 mg BID in a study by Momeni et al.27

Rahnama et al. compared the effectiveness of quadruple treatment including licorice to the same regimen using bismuth in substitution of licorice in patients with PUD. The eradication rates were 45% and 75% with licorice and bismuth, respectively, showing higher effectiveness with the regimen including licorice.26 Momeni et al. compared the same two quadruple regimens and showed similar eradication rates and concluded that D-Reglis can be a substitute for bismuth in quadruple regimen.27

In patients with PUD our results showed significantly higher eradication rate of H. pylori in the LR group compared with the control group (p = 0.03), in line with the report by Rahnama et al. However, the eradication rate with licorice was not different from the control group in patients with dyspepsia (p = 0.18), as found by Momeni et al. The discrepancy between the results reported by Rahnama et al. and Momeni et al. is due to the of patients studied. Rahnama et al. evaluated the H. pylori eradication in patients with PUD whereas the study by Momeni et al. entered patients with both PUD and NUD.

Another debatable issue regarding the effect of licorice on H. pylori eradication is the duration of treatment for improving patients’ symptoms of dyspepsia. In a clinical study Raveendra et al. evaluated the effect of licorice against placebo in functional dyspepsia and found that those who received licorice for one month had a lower Nepean Dyspepsia Index and therefore showed better improvement of symptoms compared to those who received placebo.28

In a study by Sreenivasulu Puram et al. patients suffering for dyspepsia with H. pylori infection were prescribed licorice at a dose of 120 mg a day for 60 days. The response rate was compared against the placebo using the HPSA test on days 30 and 60; showing that HPSA test on day 60 was negative in 56% of licorice group against 4% with placebo denoting a statistically significant difference.21

Based on above two studies it seems that licorice in dyspepsia, besides its antimicrobial nature in H. pylori infection, has also anti-inflammatory effect. Therefore, generally speaking prescribing licorice for H. pylori eradication at a higher dose, and longer duration should also be considered.

Conclusion

Because of the unsatisfactory rate of H. pylori eradication by the standard triple regimen, especially in areas with high resistance rates to clarithromycin and amoxicillin, adding licorice to the triple regimen significantly increase H. pylori eradication in patients with PUD.

Finally, it is recommended to use licorice in addition to the triple regimen as first line treatment in order to decrease drug adverse effects and its cost, and to increase patient compliance.

Authors’ contribution

-

i)

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: Ali Akbar Hajiaghamohammadi, Sedigheh Reisian, Sonia Oveisi, Rasoul Samimi.

-

ii)

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Ali Akbar Hajiaghamohammadi, Sedigheh Reisian, Sonia Oveisi, Ali Zargar.

-

iii)

Final approval of the version to be published; Ali Akbar Hajiaghamohammadi, Sedigheh Reisian, Sonia Oveisi, Ali Zargar and Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; Ali Akbar Hajiaghamohammadi, Sedigheh Reisian, Sonia Oveisi.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Authors of this article are thankful for the valuable cordial and dedicated cooperation of staffs in Clinical Research Development Unit of Velayat hospital.

References

- 1.Hunt R.H., Xiao S.D., Megraud F., et al. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2011;20:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens S.R., Smith L.B. Molecular aspects of H. pylori-related MALT lymphoma. Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:1931–1949. doi: 10.4061/2011/193149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balakrishnan V., Pillai M.V., Raveendran P.M., Nair C.S. Deglycyrrhizinated liquorice in the treatment of chronic duodenal ulcer. J Assoc Physicians India. 1978;26:811–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins R.J., Girardi L.S., Turney E.A. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: a review. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1244. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine L., Hopkins R.J., Girardi L.S. Has the impact of Helicobacter pylori therapy on ulcer recurrence in the United States been overstated? A meta-analysis of rigorously designed trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1409. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.452_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moayyedi P., Soo S., Deeks J., et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD002096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002096.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McColl K.E. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Eng J Med. 2010;362:1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An B., Moon B.S., Kim H., et al. Antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains and its effect on H. pylori eradication rates in a single center in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:415–419. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.6.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincenzo D.F., Floriana G., Cesare H., et al. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hikino H. In: Economic and medicinal plant research. Wagner H., Hikino H., Farnsworth N.R., editors. Academic Press; London, UK: 1985. Recent research on oriental medicinal plants; pp. 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng L., Li S.H., Lou Z.C. Morphological and histological studies of Chinese licorice. Acta Pharm Sin. 1988;23:200–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaya J., Belinky P.A., Aviram M. Antioxidant constituents from licorice roots: isolation, structure elucidation and antioxidative capacity toward LDL oxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:302–313. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shibata S. A drug over the millennia: pharmacognosy, chemistry, and pharmacology of licorice. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2000;120:849–862. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.120.10_849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zore G.B., Winston U.B., Surwase B.S., et al. Chemoprofile and bioactivities of Taverniera cuneifolia (Roth) Arn.: a wild relative and possible substitute of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong S., Inoue A., Zhu Y., Tanji M., Kiyama R. Activation of rapid signaling pathways and the subsequent transcriptional regulation for the proliferation of breast cancer MCF-7 cells by the treatment with an extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra root. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:2470–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aly A.M., Al-Alousi L., Salem H.A. Licorice: a possible anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcer drug. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2005;6:E74–E82. doi: 10.1208/pt060113. article 13, Dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottenbacher R., Blehm J. An unusual case of licorice-induced hypertensive crisis. S D Med. 2015;68:346–347. 349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melanie grimes licorice treats peptic ulcers and Helicobacter pylori infection. 2009; Available from: http://Naturalnews.com/search do: licorice (accessed 10.10.2014).

- 19.Chatterji M., Unniraman S., Mahadevan S., Nagaraja V. Effect of different classes of inhibitors on DNA gyrase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:479–485. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wittschier N., Faller G., Hensel A. Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from liquorice roots (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) inhibit adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric mucosa. 2009;125:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puram S., Suh H.C., Kim S.U., Bethapudi B., Joseph J.A., Agarwal A., Kudiganti V. Effect of GutGard in the management of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:263805. doi: 10.1155/2013/263805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett A., Clark-Wibberley T., Stamford I.F., Wright J.E. Aspirin-induced gastric mucosal damage in rats: cimetidine and deglycyrrhizinated liquorice together give greater protection than low doses of either drug alone. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1980;32:151. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1980.tb12879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldman R.A. In: Helicobacter pylori: molecular and cellular biology. Achtman M., Suerbaum S., editors. Horizon Scientific Press; Wymondham, UK: 2001. Epidemiologic observations and open questions about disease and infection caused by Helicobacter pylori; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukai T., Marumo A., Kaitou K., Kanda T., Terada S., Nomura T. Anti-Helicobacter pylori flavonoids from licorice extract. Life Sci. 2002;71:1449–1463. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asha M.K., Debraj D., Prashanth D., et al. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of a flavonoid rich extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra and its probable mechanisms of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marjan R., Davood M., Sara J., Majid E., Mehdi S.F. The healing effect of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) on Helicobacter pylori infected peptic ulcers. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:532–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali M., Ghorbanali R., Abass K., Masoud A., Soleiman K. Effect of licorice versus bismuth on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Pharmacognosy Res. 2014;6:341–344. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.138289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raveendra K.R., Jayachandra Srinivasa V., Sushma K.R., Allan J.J., Goudar K.S., Shivaprasad H.N., Venkateshwarlu K., Geetharani P., Sushma G., Agarwal A. Extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra (GutGard) alleviates symptoms of functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:216970. doi: 10.1155/2012/216970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]