Abstract

Background:

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a first-line treatment for EoE, but data are limited concerning response durability. We aimed to determine long-term outcomes in EoE patients responsive to PPI-therapy.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of newly diagnosed adults with EoE who had initial histologic response (<15 eosinophils per high-power-field) to PPI-only therapy. We extracted data regarding their subsequent clinical course and outcomes. We compared findings between the initial PPI- response endoscopy and the final endoscopy, and assessed factors associated with loss of PPI response.

Results:

Of 138 EoE patients with initial histologic response to PPI, 50 had long-term endoscopic follow-up, 40 had clinical follow-up, 10 changed treatments, and 38 had no long-term follow-up. Of those with endoscopic follow-up, mean follow-up-time was 3.6±2.9 years; 30 and 32 patients (60%; 64%) maintained histologic and symptom responses, respectively. However, fibrotic endoscopic findings of EoE were unchanged. Younger age (aOR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.11) and dilation prior to PPI treatment (aOR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.83) were the only factors associated with long-term loss of PPI response.

Conclusions:

Long-term histologic and clinical response rates for PPI therapy were 60% and 64%, respectively. Younger age and dilation at baseline were associated with histologic loss of response. These data can inform long-term EoE treatment selection.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, proton pump inhibitor, outcomes, response rates, histology

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, TH2-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by an abnormal accumulation of eosinophils in the esophageal epithelium and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction.1 It is an increasingly prominent cause of upper gastrointestinal morbidity, and has an outsized health care burden for a rare disease.2,3 Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have historically had an important role in the management of EoE.4 Initially, a “PPI trial” was used to distinguish gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a disease that shares many clinical features, and EoE, with improvement indicating GERD was the cause of esophageal eosinophilia and failure of PPI treatment diagnostic for EoE.5 The clinical dichotomy was not this simple, however, as patients who appeared to have EoE and have no evidence of reflux disease would still appear to respond to PPIs. While this subgroup was initially classified as PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE), it is now clear that these are often EoE patients who respond to PPI treatment.4,6–8 Accordingly, the most recent diagnostic guidelines have eliminated the requirement for a PPI trial and have instead placed PPIs in the therapeutic algorithm.9,10

Efficacy of PPIs for EoE are supported by several lines of data and potentially novel mechanisms.11–13 A recently conducted meta-analysis found that approximately 50% of patients with what would now be termed EoE achieved histological remission from PPI therapy.14 This study also revealed that 60% of patients had symptomatic improvement after PPI use.10,14 One limitation of the studies included in this prior meta-analysis was that the patients were not truly diagnosed with EoE at the time (they were either considered to be GERD or PPI-REE patients), and only initial treatment courses were assessed. While the short-term outcomes of PPI therapy have been reported, few studies have reported long-term outcomes.15,16

This study hopes to address these gaps by assessing long-term clinical, endoscopic, and histologic outcomes of PPI treatment in a retrospective cohort of EoE patients who were found to be initially PPI-responsive. We also aimed to examine the impact of different dosing regimens on efficacy, to explore what clinical features, if any, were associated with eventual PPI non-response, and in so doing, clarify the role of PPIs among the different treatment regimens available for the long-term management of EoE patients.

Methods

Study design and patient population

We performed a retrospective cohort study of newly diagnosed EoE patients ≥18 years who were identified with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilia (>15 eosinophils per high-power field; eos/hpf), in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia, after upper endoscopy performed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). To be eligible for the present study, we further selected patients who were responsive to high dose PPI-only therapy (at a total daily dose of 40–80 mg of any of the approved medications, for at least 8 weeks), as defined by a post-treatment peak esophageal eosinophil count of <15 eos/hpf. The data source was the UNC EoE Clinicopathologic Database, which contains clinical, endoscopic, and histologic information at the time of diagnosis, and which has been previously described.17–20 Importantly, patients who were previously felt to be PPI responsive (or who were diagnosed with PPI-REE rather than EoE at the time, but who by current guidelines would be classified as EoE), were also tracked. This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board and because this was a retrospective study, a waiver of consent was granted.

Data collection and outcomes

After case selection, we extracted additional data from the medical record relating to demographics (age, sex), comorbidities (particularly atopy background), clinical symptoms, endoscopic findings (edema, rings, exudates, furrows, strictures, narrowing, and whether dilatation was performed), and histologic findings at the time of diagnosis from the database. Then, using standardized case-report forms, we extracted additional data regarding treatment details and outcomes from the electronic medical record for subsequent endoscopy or clinical encounters that were available. We recorded initial PPI dosing, any dose reduction, length of PPI treatment, and final dose at the end of available follow-up.

The primary outcome was histological response (defined as <15 eos/hpf 21–23) at the end of available follow-up, and we also performed selected subanalyses with a more stringent threshold (<5 eos/hpf). Additional outcomes were severity of endoscopic findings, as quantified by the validated EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS),24,25 though this was not available for all patients given that our database spanned back prior to the development of EREFS. As this was a retrospective study and validated patient-reported outcome data were not available, we also assessed global patient-reported symptom response as documented by the provider at the time of the last endoscopy on record, which has been an effective measure in prior studies.19,20,26,27

Statistical analysis and sample size considerations

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of the study population. Patients were divided into those with endoscopic follow-up and those with clinical follow-up only, recording PPI dosing of time and length of follow-up. We compared findings between patients with different PPI dosing strategies (e.g. final dose unchanged, lowered, or increased), using two sample t-tests or ANOVA for continuous variables, and Chi squared for categorical variables. We also compared the outcomes of the initial PPI-response endoscopy and the final documented endoscopy, using paired t-tests for continuous variables and McNemar’s test for categorical variables, for the within group, pre/post treatment analysis. For the primary analyses, all PPI doses were assessed in mg, without adjusting for the specific PPI, as a majority of patients (>80%) were treated with omeprazole or esomeprazole. We then compared the patients who maintained histologic response (<15 eos/hpf) to those who lost histologic response to PPI over time. We used multivariate logistic regression to determine factors associated with loss of PPI response. The model was developed with factors from the bivariate analysis and those that were clinically relevant, and then the model was reduced with a backwards elimination approach (10% change threshold). In subsequent analyses that recapitulated the primary analysis, we categorized PPIs as per the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology which established standard doses of PPI as follows: omeprazole 20 mg, pantoprazole 40mg, esomeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg and rabeprazole 20 mg daily.28 This allowed us to assess the data based on single/standard dosing, double dosing, or quadruple dosing, both at baseline and at the final endoscopic follow-up. Analyses were performed using Stata version 12 (College Station, TX).

Results

Patient characteristics, treatment, and follow-up

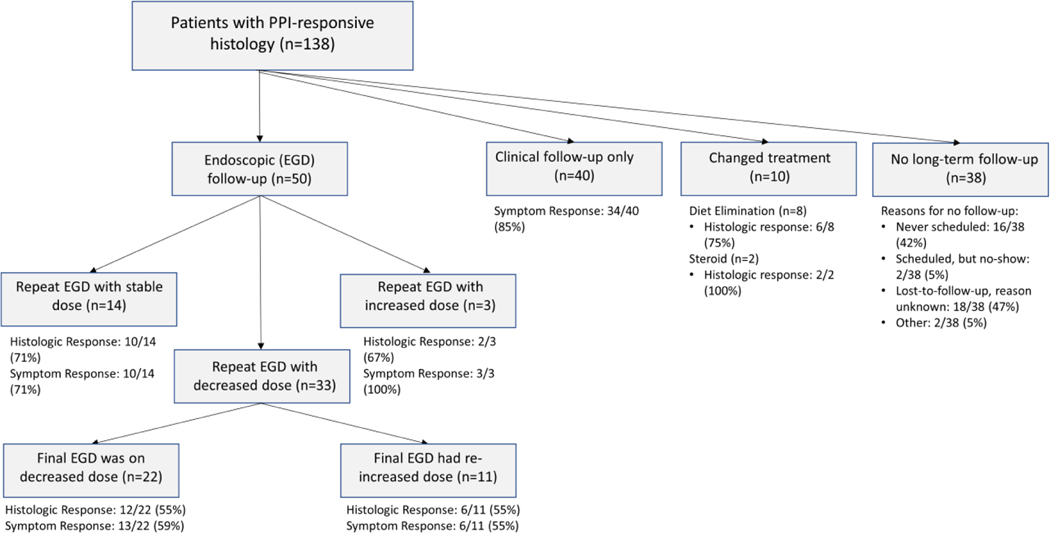

We identified 138 newly diagnosed adult EoE patients with an initial histologic response to PPI therapy (mean age 44.7±14.7 years; 62% male; 92% white), representing a 35% PPI response rate in the context of the 389 EoE patients newly diagnosed over the study time frame. Of this PPI-responsive group, 50 (36%) had subsequent endoscopic follow-up (mean follow-up time 3.6±2.9 years), 40 (29%) had only clinical follow-up (mean follow-up time 2.4±2.1 years), 10 (7%) changed treatments to a non-PPI therapy, and 38 (28%) had no long-term follow-up after their initial PPI response (Figure 1). Among those who lacked follow-up, 16 (42%) patients were never scheduled for a follow-up visit. There were no substantial differences in baseline clinical, endoscopic, or histologic characteristics for the different follow-up groups (Supplemental Table 1). Within the endoscopic follow-up group, 14 maintained stable PPI dosing, 3 had increased dosing, and 33 had decreased dosing (with 22 patients continuing this lower dose on their final endoscopy while 11 patients had a final endoscopy with a re-increased PPI dose) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flow-diagram for patient stratification by PPI course and outcomes following endoscopy demonstrating PPI-response.

Within the endoscopic follow-up group (mean age 45.1±13.9 years; 58% male; 92% white), baseline patient demographics such as age, sex, and race, presenting symptoms, frequency of atopy, and endoscopic features did not vary significantly among the four sub-groups with different PPI dosing strategies; peak eosinophil counts before and after initial PPI therapy were also similar (Table 1). However, the mean follow-up time for the group in which the final PPI dose was re-increased had an average longer follow-up time of 6.8±3.6 years compared with the groups that had the dose unchanged, increased, or lowered (2.4±1.8 years, 2.8±3.1 years, and 2.8±1.9 years, respectively; p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics by final long-term PPI dose regimen in patients with endoscopic follow-up (n = 50)

| Final dose unchanged (n = 14) |

Final dose increased (n = 3) |

Final dose lowered (n = 22) |

Final dose re-increased (n = 11) |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 47.7 ± 14.2 | 40.1 ± 9.0 | 46.5 ± 14.9 | 40.7 ± 12.5 | 0.55 |

| Male (n, %) | 9 (64) | 2 (67) | 10 (45) | 8 (73) | 0.44 |

| White (n, %) | 12 (86) | 3 (100) | 21 (95) | 10 (91) | 0.71 |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |||||

| Dysphagia | 14 (100) | 3 (100) | 22 (100) | 11 (100) | -- |

| Heartburn | 7 (50) | 1 (33) | 4 (18) | 1 (9) | 0.09 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (21) | 1 (33) | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.34 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 3 (21) | 1 (33) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.34 |

| Atopy (n, %) | |||||

| Seasonal allergies | 7 (50) | 2 (67) | 16 (73) | 4 (36) | 0.21 |

| Asthma | 5 (36) | 2 (67) | 7 (32) | 1 (9) | 0.22 |

| Food allergies | 2 (14) | 2 (67) | 5 (23) | 1 (9) | 0.15 |

| Eczema | |||||

| Endoscopic findings (n, %) | |||||

| Rings | 10 (71) | 0 (0) | 12 (55) | 10 (91) | 0.02 |

| Stricture | 6 (43) | 1 (33) | 7 (32) | 4 (36) | 0.93 |

| Narrowing | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) | 2 (18) | 0.76 |

| Furrows | 7 (50) | 1 (33) | 15 (68) | 8 (72) | 0.42 |

| Exudates | 7 (50) | 0 (0) | 8 (36) | 6 (55) | 0.32 |

| Edema | 4 (29) | 0 (0) | 9 (41) | 4 (36) | 0.53 |

| Dilation performed | 5 (34) | 2 (67) | 11 (50) | 4 (37) | 0.66 |

| Peak eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) | |||||

| Pre-PPI treatment | 65.2 ± 41.0 | 83.3 ± 93.6 | 61.1 ± 38.3 | 71.7 ± 72.8 | 0.88 |

| Post-PPI treatment | 4.7 ± 5.1 | 9.8 ± 4.0 | 5.5 ± 4.4 | 4.1 ± 4.3 | 0.28 |

| Mean follow-up time (years ± SD) | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 3.1 | 2.8 ± 1.9 | 6.8 ± 3.6 | < 0.001 |

| PPI medication type (n, %) | 0.12 | ||||

| Dexlansoprazole | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Mean daily dose† (mg ± SD) | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Esomeprazole | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 4 (18) | 2 (18) | |

| Mean daily dose (mg ± SD) | 40 ± 0 | -- | 70 ± 20 | 80 ± 0 | |

| Lansoprazole | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 2 (18) | |

| Mean daily dose (mg ± SD) | 60 ± 0 | -- | 60 ± 0 | 60 ± 0 | |

| Omeprazole | 7 (50) | 2 (67) | 17 (77) | 7 (64) | |

| Mean daily dose (mg ± SD) | 40 ± 0 | 40 ± 0 | 44.7 ± 0 | 40 ± 0 | |

| Pantoprazole | 4 (29) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Mean daily dose (mg ± SD) | 60 ± 23.1 | 40 ± 0 | -- | -- | |

| PPI dose category (n, %)‡ | 0.08 | ||||

| Single/standard | 2 (14) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Double | 12 (86) | 2(67) | 17 (77) | 9 (82) | |

| Quadruple | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (23) | 2 (18) |

Means compared with means compared with ANOVA, proportions compared with Chi squared

There were no statistically significant differences between the mean doses for any of the PPIs

Categorization based one standard doses as follows: omeprazole 20 mg, pantoprazole 40mg, esomeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, with double and quadruple calculated accordingly; no patients received rabeprazole.

When assessing the specific PPIs, doses used, and dose categories (single/standard, double, or quadruple), these did not vary in the overall study population (Supplemental Table 1) or in those who had endoscopic follow-up (Table 1). Most patients were treated with either omeprazole or esomeprazole, and at double or quadruple doses at baseline.

Long-term response outcomes

Among the 50 patients with endoscopic follow-up, 30 (60%) had ongoing histologic response (<15 eos/hpf) on PPI therapy at the time of their final endoscopy, and 32 (64%) had continued symptom control (Table 2). The peak eosinophil count dropped from an average of 65.9±50.7 eos/hpf at baseline (prior to PPI) to 5.2±4.6 eos/hpf after initial PPI therapy, and then increased somewhat to 22.0±33.0 eos/hpf on final endoscopy. The mean PPI dose decreased from the initial PPI response endoscopy (49 ± 16 mg) to the final endoscopy (40 ± 19 mg). Improvements in many endoscopic findings that were seen after the initial PPI treatment were maintained, but strictures persisted and required ongoing dilation (Table 2). When these 50 subjects were stratified by their final dosing groups, there were some numerical, but not significant, differences in histologic response rates at the end of follow-up (Supplemental Table 2). For the stable dose group (n=14), the final PPI dose was 46 mg, and the histologic response rate was 71%. For the group with dose increases (n=3), dose decrease maintained (n=22), and dose re-increased (n=11), dosing and histologic response rates were 80 mg and 67%, 26 mg and 55%, and 51 mg and 55%. When we examined the stricter histologic response threshold of <5 eos/hpf, we found that 67 of the 138 included PPI-responsive subjects (49%) achieved this outcome.

Table 2:

Long-term treatment outcomes for EoE patients responsive to PPI treatment with endoscopic follow-up (n = 50)

| Baseline (no PPI) | Initial PPI response | Final endoscopy | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily total PPI (mean mg ± SD) | -- | 49 ± 16 | 40 ± 19 | 0.004 |

| PPI dose category (n, %)† | ||||

| Single/standard | -- | 3 (6) | 21 (41) | < 0.001 |

| Double | -- | 40 (80) | 26 (52) | |

| Quadruple | -- | 7 (14) | 3 (6) | |

| Endoscopic findings (n, %) | ||||

| Rings | 32 (64) | 26 (52) | 19 (38) | 0.06 |

| Stricture | 18 (36) | 22 (44) | 23 (46) | 0.73 |

| Narrowing | 6 (12) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 0.56 |

| Furrows | 31 (62) | 21 (42) | 15 (30) | 0.11 |

| Exudates | 21 (42) | 6 (12) | 9 (18) | 0.41 |

| Edema | 17 (34) | 9 (18) | 11 (22) | 0.59 |

| Dilation | 22 (44) | 19 (38) | 23 (46) | 0.32 |

| Total EREFS score | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.62 |

| Peak eosinophil count | ||||

| Mean eos/hpf ± SD | 65.9 ± 50.7 | 5.2 ± 4.6 | 22.0 ± 33.0 | < 0.001 |

| Median eos/hpf (IQR) | 50 (35–75) | 5 (2–8)) | 8 (0–34) | 0.005 |

| Histologic response (n, %) | ||||

| <15 eos/hpf | -- | 50 (100) | 30 (60) | < 0.001 |

| <5 eos/hpf | -- | 23 (46) | 22 (44) | 0.82 |

| Symptom response (n, %) | 50 (100) | 32 (64) | < 0.001 |

Comparison between initial PPI response endoscopy and final endoscopy; means compared with paired t-tests, proportions compared with McNemar’s test, medians compared with Wilcoxon Signed-rank

Categorization based one standard doses as follows: omeprazole 20 mg, pantoprazole 40mg, esomeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, with double and quadruple calculated accordingly; no patients received rabeprazole

When patients with endoscopic follow-up were stratified by symptom response, histologic response tracked with overall symptom response (Table 3). Among symptom responders (n=32), average peak eosinophil counts on final endoscopy were 4.1 ± 6.5 eos/hpf with a 94% histologic response rate, while eosinophil counts in symptom non-responders were 54.2 ± 36.8 eos/hpf with no histologic responders (p<0.001). Symptom responders also had fewer strictures (31% vs 72%; p=0.005) and had numerically fewer dilations. Interestingly, the final PPI dose among symptom responders and non-responders did not vary significantly (Table 3). Finally, in those who had only clinical follow-up, 34 patients (85%) reported continued symptom control on PPIs (Figure 1).

Table 3:

Outcomes among symptom responders and non-responders on final endoscopy

| Symptom Non-responders (n = 18) |

Symptom Responders (n = 32) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) | 54.2 ± 36.8 | 4.1 ± 6.5 | < 0.001 |

| Histologic response < 15 eos/hpf (n, %) | 0 (0) | 30 (94) | < 0.001 |

| Required dilation at final EGD (n, %) | 11 (61) | 12 (38) | 0.11 |

| Stricture present at final EGD (n, %) | 13 (72) | 10 (31) | 0.005 |

| Narrowing present at final EGD (n, %) | 2 (11) | 1 (3) | 0.25 |

| Esophageal diameter at final EGD (mean mm ± SD) |

15.4 ± 2.8 | 16.4 ± 1.4 | 0.37 |

| Final PPI dose (mean daily mg ± SD) | 38.3 ± 18.9 | 40.9 ± 19.7 | 0.65 |

On additional analyses based on the final PPI dose categorizations for the 50 patients with endoscopic follow-up, we found similar results. There were no baseline demographic, endoscopic, or histologic differences by final PPI dose categories (single/standard, double, and quadruple; Supplemental Table 3), and similarly no differences in final endoscopic, histologic, or symptom outcomes by the dose categories (Supplemental Table 4).

Predictors of loss of response

When comparing patients who lost histologic response to those who maintained response at the final endoscopic follow-up, there were few characteristics that were associated with non-response. Specifically, the demographics, baseline symptoms, atopic status, pre- and post-PPI endoscopic findings, eosinophil counts, follow-up times, and PPI doses were generally similar between the groups, though there was a trend for pre-PPI dilation being more common in ultimate non-responders (60% vs 33%; p=0.06) (Table 4). On multivariate analysis, younger age (aOR 1.05 per year, 95% CI: 1.01–1.11) and initial dilation prior to PPI treatment (aOR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.83) were the only factors independently associated with long-term loss of PPI response, after accounting for the final PPI dose (Supplemental Table 5). Results were unchanged after assessing PPI dose category. When we examined the more stringent histologic response threshold (<5 eos/hpf) at baseline, this was not a predictor of response either: there were of 15 of 30 pts (50%) who had an initial response of <5 eos/hpf who maintained remission on their final endoscopy compared to 8 of 12 (40%) who did not maintain remission (p=0.49).

Table 4:

Comparison of histologic responders (<15 eos/hpf) and non-responders (≥15 eos/hpf) on final endoscopy

| Non-responders (n = 20) |

Responders (n = 30) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 41.6 ± 14.5 | 47.5 ± 13.2 | 0.15 |

| Male (n, %) | 11 (55) | 18 (60) | 0.73 |

| White (n, %) | 18 (90) | 28 (93) | 0.67 |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |||

| Dysphagia | 20 (100) | 30 (100) | -- |

| Heartburn | 3 (15) | 10 (33) | 0.15 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (10) | 5 (17) | 0.51 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (10) | 5 (17) | 0.51 |

| Atopy (n, %) | |||

| Seasonal allergies | 12 (60) | 17 (57) | 0.82 |

| Asthma | 8 (40) | 7 (23) | 0.21 |

| Food allergies | 6 (30) | 6 (20) | 0.42 |

| Eczema | 7 (35) | 3 (10) | 0.03 |

| Pre-PPI endoscopic findings (n, %) | |||

| Rings | 15 (75) | 17 (57) | 0.19 |

| Stricture | 9 (45) | 9 (30) | 0.28 |

| Narrowing | 3 (15) | 3 (10) | 0.59 |

| Furrows | 13 (65) | 18 (60) | 0.72 |

| Exudates | 8 (40) | 13 (43) | 0.82 |

| Edema | 7 (35) | 10 (33) | 0.90 |

| Dilation performed | 12 (60) | 10 (33) | 0.06 |

| Post-PPI endoscopic findings (n, %) | |||

| Rings | 8 (40) | 18 (60) | 0.17 |

| Stricture | 10 (50) | 12 (40) | 0.49 |

| Narrowing | 2 (10) | 2 (7) | 0.67 |

| Furrows | 11 (55) | 10 (33) | 0.13 |

| Exudates | 1 (5) | 5 (17) | 0.21 |

| Edema | 4 (20) | 5 (17) | 0.76 |

| Dilation performed | 7 (35) | 12 (40) | 0.72 |

| Peak eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) | |||

| Pre-PPI treatment | 68.5 ± 63.4 | 64.1 ± 40.9 | 0.77 |

| Post-PPI treatment | 5.7 ± 4.8 | 4.9 ± 4.6 | 0.58 |

| Initial histologic response <5 eos/hpf) | 8 (40) | 15 (50) | 0.49 |

| Mean follow-up time (years ± SD; range) | 3.7 ± 2.9 | 3.4 ± 3.0 | 0.76 |

| PPI dose (mean total daily dose ± SD) | |||

| Initial dosing | 49.0 ± 15.2 | 49.3 ± 16.4 | 0.94 |

| Final dosing | 39.5 ± 20.6 | 40.3 ± 18.7 | 0.88 |

| PPI dose decreased (n, %) | 15 (75) | 18 (60) | 0.27 |

Discussion

While PPIs have been shown to improve histology and symptoms in EoE, few studies have examined PPI durability and how response may vary with long-term dosing changes.10,14 We analyzed a retrospective cohort to address this topic. In those who showed initial histologic response to PPI therapy, we found that 60% of patients maintained histologic response by their last endoscopy and 64% of patients maintained symptomatic response at an average of 3.6 years of follow-up. This response did not seem to be strongly dependent on final PPI dosing. In those who only had clinical follow-up, 85% of patients endorsed full symptom control. Apart from esophageal dilation prior to PPI initiation, no other clinical factors except slightly younger age were associated with eventual loss of response. Our data suggest that PPIs may be less effective in remediating the fibrotic and structural changes associated with EoE, which is consistent with mechanistic data showing PPI-related decreased Th2 cytokine-induced eotaxin-3 expression from the esophageal epithelium had a lack of effect on fibroblasts.11,29–31 While findings from a recent study did suggest a decrease in endoscopic features of fibrosis with PPI treatment32, in our data we could not replicate this, even with assessing more stringent histologic thresholds. We also did not find many predictors of long-term histologic response, which is consistent with prior work that also did not identify predictors of initial PPI response.7 A recent study in a pediatric cohort found male sex, symptoms of dysphagia and food impaction, and absence of heartburn, and endoscopy findings of furrows and exudates could predict response33, and future work could see if this model could be validated in adults and with a longer time horizon.

Existing studies with data on long-term PPI efficacy offer insights into how we might contextualize our results. One retrospective cohort study found a histological efficacy of 73% among 75 PPI-REE patients with a mean follow-up time of 2.2 years.15 This study also reported 10% of patients with a stable PPI dose relapsed and 25% with a decreased dose relapsed, and our data trend similarly in this regard. Our results overall, however, show a greater loss-of-response, but our study was also conducted over a longer time-interval, possibly suggesting a continued decrease in response over time. A cross-sectional study analyzing data from the EoE CONNECT database found that PPI efficacy diminished with increased treatment length, with rates of remission at 75% if examined within the first 2–3 months of initiation, but dropping to 69% when examined at greater than 6 months.16 One prospective pediatric study showed a histologic efficacy of 70% after 12 months of follow-up.34 That study also found that 86% of patients maintained full symptom control, which corroborates with our findings in adults.

Multiple studies have examined the long-term efficacy of swallowed topical corticosteroid (tCS) therapy, offering a useful comparison to PPIs as the current predominant alternative pharmacologic approach. One retrospective study of the Swiss EoE database with a median follow-up period of 5 years reported that 49.2% of participants on tCS maintained long-term histologic remission.35 However, this study also excluded patients who were initially responsive to PPIs. An earlier analysis from a similar UNC cohort found that only 39% of patients achieved long-term histologic remission after a median follow-up of 11.7 months, although a greater proportion of patients who had a stable dose maintained remission more than those with a reduced dose.27 A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial studying the efficacy of budesonide orodispersable tablets found approximately 75% of participants maintained histologic remission after a 48-week period,36 and rates of remission have ranged from 39–76% with a budesonide suspension for an additional 6 months.37–40 An open-label, prospective pediatric clinical study demonstrated an efficacy of 63% in patients who received fluticasone in a follow-up interval exceeding 24 months.41 Interestingly, there are two randomized controlled trials of swallowed fluticasone vs esomeprazole in treatment naïve patients who would now be recognized to have EoE, and results were roughly similar between the agents. However, these studies were relatively small and used lower dosing than would be used now.42,43 A large-scale randomized trial directly comparing the two pharmacologic agents with long-term follow-up would be an optimal next step.

One important limitation to our study was an inability to assess for medication adherence, which may have added greater clarity to the attributes distinguishing histologic responders from non-responders, among other findings, and lack of adherence could underestimate medication efficacy and make long term response rates somewhat unreliable. Moreover, we did not assess for presence of CYP2C19 or STAT6 variants, which have been demonstrated to influence response to PPI treatment.15,44 In addition, our analysis was retrospective and limited to adult-only data from a single center. However, the data obtained was comprehensive and the sample size was relatively large for a study of PPI responders. The cohort design also permitted the analysis of the long-term trajectory of PPI usage, including modifications to dosing regimens. One further limitation to our study was the lack of validated metrics in assessing symptoms, which were not available with the retrospective design, and we acknowledge that a global symptom response cannot be equated with a precise reduction in symptom severity as measured by a validated instrument. In contrast, we had eosinophil counts and endoscopic findings as objective outcome metrics. Finally, since we identified no major differences in the baseline characteristics for each of the four groups stratified by follow-up status or by final PPI dose regimen, it did not seem that selection bias would impact the interpretation of the results.

In conclusion, we found that PPIs are 60% effective in maintaining histologic remission for more than 3 years in those who are initially responsive, with higher symptom response rates noted in those with only clinical follow-up. We also found that initial dilation prior to PPI initiation was associated with ultimate loss of response, though the mechanism of this finding needs to be elucidated. These data can help inform long-term treatment selection in EoE. Future studies may consider stratifying the analysis further by type of proton-pump inhibitor and the minimum dosage needed for maximizing efficacy, assessing how other drugs may confound the effects of PPIs in the long term, including a prospective assessment of molecular markers of response, and clarifying which patients will benefit the most from PPIs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This study was supported by NIH T35 DK007386

Potential competing interests: Dr. Dellon is a consultant for Abbott, Abbvie, Adare/ Ellodi, Aimmune, Allakos, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Avir, Biorasi, Calypso, Celgene/Receptos/BMS, Celldex, Eli Lilly, EsoCap, GSK, Gossamer Bio, InveniAI, Landos, LucidDx, Morphic, Nutricia, Parexel/Calyx, Phathom, Regeneron, Revolo, Robarts/Alimentiv, Salix, Sanofi, Shire/Takeda, Target RWE, receives research funding from Adare/Ellodi, Allakos, Arena, AstraZeneca, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos/BMS, Regeneron, Shire/Takeda, and has received an educational grant from Allakos, Banner, and Holoclara. None of the other authors report and potential conflicts of interest with this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.O’Shea KM, Aceves SS, Dellon ES, et al. Pathophysiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):333–345. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):319–332.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen ET, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Dellon ES. Health-care utilization, costs, and the burden of disease related to eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(5):626–632. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eluri S, Dellon ES. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic oesophagitis: More similarities than differences. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31(4):309–315. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Consensus Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment: Sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute and North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterol. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4):1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina-Infante J, Bredenoord AJ, Cheng E, et al. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia: An entity challenging current diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2016;65(3):521–531. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics do not reliably differentiate PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(12):1854–1860. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Markers of eosinophilic inflammation for diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis and proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2015–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1022–1033.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Ngel Arias Á, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(3):335–358. doi: 10.1177/2050640616689525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng E, Zhang X, Huo X, et al. Omeprazole blocks eotaxin-3 expression by oesophageal squamous cells from patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis and GORD. Gut. 2013;62(6):824–832. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rhijn BD, Weijenborg PW, Verheij J, et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Partially Restore Mucosal Integrity in Patients With Proton Pump Inhibitor–Responsive Esophageal Eosinophilia but Not Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(11):1815–1823.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochman M, Xie YM, Mack L, et al. Broad transcriptional response of the human esophageal epithelium to proton pump inhibitors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(5):1924–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, Molina-Infante J. SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS AND META-ANALYSES Efficacy of Proton Pump Inhibitor Drugs for Inducing Clinical and Histologic Remission in Patients With Symptomatic Esophageal Eosinophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Published online 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molina-Infante J, Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Martinek J, et al. Long-term loss of response in proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia is uncommon and influenced by CYP2C19 genotype and rhinoconjunctivitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1567–1575. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Casabona S, Guagnozzi D, et al. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic oesophagitis in 630 patients: results from the EoE connect registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;(May):1–10. doi: 10.1111/apt.15957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Findings Distinguish Eosinophilic Esophagitis From Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(12):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed CC, Corder SR, Kim E, et al. Psychiatric Comorbidities and Psychiatric Medication Use Are Highly Prevalent in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Associate with Clinical Presentation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(6):853–858. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed CC, Tappata M, Eluri S, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Combination Therapy With Elimination Diet and Corticosteroids Is Effective for Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(13):2800–2802. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eluri S, Runge TM, Cotton CC, et al. The extremely narrow-caliber esophagus is a treatment- resistant subphenotype of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(6):1142–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ, et al. Evaluation of histologic cutpoints for treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. Published online 2015. doi: 10.17554/j.issn.2224-3992.2015.04.562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed CC, Wolf WA, Cotton CC, et al. Optimal Histologic Cutpoints for Treatment Response in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Analysis of Data From a Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellon ES, Gupta SK. A Conceptual Approach to Understanding Treatment Response in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, Thomas CS, Gonsalves N, Achem SR. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: Validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. Published online 2013. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dellon ES, Cotton CC, Gebhart JH, et al. Accuracy of the Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score in Diagnosis and Determining Response to Treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg S, Chang NC, Corder SR, Reed CC, Eluri S, Dellon ES. Dilation-predominant approach versus routine care in patients with difficult-to-treat eosinophilic esophagitis: a retrospective comparison. Endoscopy. Published online April 28, 2021. doi: 10.1055/a-1493-5627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eluri S, Runge TM, Hansen J, et al. Diminishing Effectiveness of Long-Term Maintenance Topical Steroid Therapy in PPI Non-Responsive Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8(6):e97. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2017.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham DY, Tansel A. Interchangeable Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors Based on Relative Potency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(6):800–808.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinoshita Y, Ishimura N, Ishihara S. Advantages and disadvantages of long-term proton pump inhibitor use. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24(2):182–196. doi: 10.5056/jnm18001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Cheng E, Huo X, et al. Omeprazole Blocks STAT6 Binding to the Eotaxin-3 Promoter in Eosinophilic Esophagitis Cells. PLoS One. Published online 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kedika RR, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Potential anti-inflammatory effects of proton pump inhibitors: A review and discussion of the clinical implications. Dig Dis Sci. Published online 2009. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0951-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro P, Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Guagnozzi D, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy reverses endoscopic features of fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53(11):1479–1485. doi: 10.1016/J.DLD.2021.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponda P, Patel C, Ahn S, Leung TM, Webster T. Integration of a clinical scoring system in the management of eosinophilic esophagitis. J allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):786–789.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutiérrez-Junquera C, Fernández-Fernández S, Cilleruelo ML, Rayo A, Román E. The role of proton pump inhibitors in the management of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Front Pediatr. 2018;6. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greuter T, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Maintenance Treatment Of Eosinophilic EsophagitisWith Swallowed Topical Steroids Alters Disease Course Over A 5-Year Follow-up Period In Adult Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):419–428.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straumann A, Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, et al. Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets Maintain Remission in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1672–1685.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Symptomatic, Endoscopic, and Histologic Parameters Compared With Placebo in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):776–786.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Budesonide Oral Suspension Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):666–673.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online December 17, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dellon ES, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al. Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis With Budesonide Oral Suspension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online December 17, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andreae DA, Hanna MG, Magid MS, et al. Swallowed Fluticasone Propionate Is an Effective Long-Term Maintenance Therapy for Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1187–1197. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson KA, Thomas KL, Hilden K, Emerson LL, Wills JC, Fang JC. Comparison of Esomeprazole to Aerosolized, Swallowed Fluticasone for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(5):1313–1319. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0859-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Dias JA, Baker TP, Maydonovitch CL, Wong RKH. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Aerosolized Swallowed Fluticasone to Esomeprazole for Esophageal Eosinophilia. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol | ACG. 2013;108(3). https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2013/03000/Randomized_Controlled_Trial_Comparing_Aerosolized.14.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mougey EB, Williams A, Coyne AJK, et al. CYP2C19 and STAT6 Variants Influence the Outcome of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;00(00):1–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.