Abstract

Background

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a neurological disorder, characterized by gait- and balance disturbance, cognitive deterioration, and urinary incontinence, combined with ventricular enlargement. Gait ability, falls, cognitive status, and health-related quality of life pre and post surgery have not previously been studied at Karolinska University Hospital.

Methods

One hundred and eighteen patients with iNPH that underwent shunt surgery at Karolinska University Hospital during the years from 2016 to 2018 were included. Results of walking tests, test for cognitive function, and self-estimated health-related quality of life, before and 3 months after surgery, were collected retrospectively as a single-center study.

Results

Walking ability, cognitive function, and health-related quality of life significantly increased 3 months after shunt surgery. A positive significant correlation was seen between a higher self-estimated quality of life and walking ability.

Conclusions

Patients with suspected iNPH treated with shunt surgery at Karolinska University Hospital improved their walking ability and cognitive functioning 3 months after shunt surgery. A positive significant correlation was seen between a higher self-estimated quality of life and walking ability but not with increased cognitive function. We then concluded that the selection of patients for shunting maintained a high standard.

Keywords: Gait ability, Falls, Cognition, Health-related quality of life, Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, Shunt surgery

Introduction

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a neurological disorder, characterized by gait- and balance disturbance, cognitive deterioration, and urinary incontinence, combined with ventricular enlargement and a moderately elevated lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [1]. While the cause of secondary NPH is known, the etiology of idiopathic NPH (iNPH) is unknown although vascular comorbidity has been proposed as a possible cause with risk factors as high blood pressure and diabetes [6]. The majority of patients are 70–80 years of age [27]. Patients suffering from iNPH are most commonly treated by diversion of CSF through a ventriculoperitoneal shunt [26]. If untreated, the hazard ratio for early death is 3.8 [16].

iNPH is characterized by a classical triad of symptoms: gait and balance disturbance, urinary incontinence, and cognitive decline. The cardinal symptom is the gait disturbance. The gait is typically broad-based and shuffling due to decreased velocity and step length as well as step height. Retropulsion and freezing of gait phenomena are also common [2]. In the early stages, gait changes can be insignificant, with progression over time. These disturbances often lead to an increased risk of falling combined with fear of falling that may contribute to loss of independence [10]. The cognitive deficits seen in iNPH are characterized by deficits in memory, visuospatial abilities, psychomotor speed, and executive function. For patients with cognitive deficits, the inability to perform activities of daily life (ADL) is the main reason of deteriorated health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Before shunting, many patients with iNPH, struggle with their ADL, have depressive symptoms, and estimate their HRQoL lower than the general population [17].

Aim

Gait ability, falls, cognitive status, and health-related quality of life pre and post surgery have not previously been studied at Karolinska University Hospital. Our aim was to investigate how these parameters varied, as well as correlated, in INPH patients evaluated by CSF tap test, selected for shunt surgery, and evaluated 3 months post surgery at Karolinska University Hospital.

Methods and materials

Data regarding Karolinska University Hospital were extracted from The Swedish Neuro Registries—a national quality registry which aims to improve the equity and quality of neurological care as well as ensure adherence to national guidelines. If data were missing in the registry, they were extracted from medical records.

The Timed Up and Go test (TUG) [22] and 10-m walk test (10MWT) [4] were used as a measure of gait. TUG is a reliable and valid test for quantifying functional gait and may also be useful in following a clinical change over time [22]. The 10MWT has a great test–retest reliability and good validity and is the most preferable short walk test in clinical research. It is also a good indicator of measuring health status [11]. Gait velocity in 10MWT was recalculated to meters per second (m/s) and used for analyses.

Cognitive status was assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE, range 0–30) [8]. The test is considered to have a satisfactory reliability and validity [25].

The 5-level EQ-5D version (EQ-5D-5L) was used for assessment of self-rated health-related quality of life. EQ-5D-5L is a reliable and valid generic instrument that describes health status in five domains. The EQ-5D visual analog scale (EQ VAS) was used to provide a global assessment of the patient’s health from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (the best imaginable health) [7].

Falls within the last 12 months, pre surgery, and 3 months post surgery were documented in the patient’s medical record. One fall or more were registered by “Yes” in the data set and no falls reported as “No.”

All tests were performed before (pre-CSF tap test) and 3 months after ventriculo-peritoneal shunt surgery. If the elapse time for surgery was more than 3 months, the patients were revaluated preoperatively.

Participants

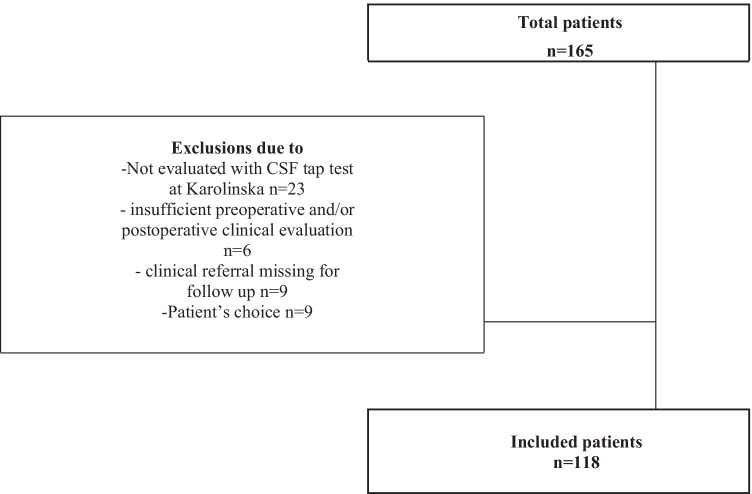

Patients diagnosed with iNPH, tap tested and underwent shunt surgery during the years of 2016–2018 at Karolinska University Hospital, were included. Patients that lacked results of gait pre- and postoperative, were excluded but no patients were excluded due to cognitive status. The flowchart of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05-level. Due to the lack of normally distributed variables, we used mainly non-parametric statistics.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used in TUG, 10MWT, MMSE, and EQ-5D-5L to determine whether there was a significant difference between the median values in the two related groups.

The dependent T test was used in EQ VAS to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between the means in the two related groups.

Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used to analyze the degree of association between the variables 10MWT, TUG, MMSE, and EQ VAS after surgery. To calculate EQ-5D-5L index, the EQ-5D-5L crosswalk index value calculator with the United Kingdom algorithm was used.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional ethical review board in Stockholm, DNR 2019–00,353.

Results

Demographics

One-hundred and sixty-five patients underwent shunt surgery at Karolinska University Hospital during the years 2016–2018. Forty-seven of the patients were excluded due to exclusion criterias, and the remaining 118 patients were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Mean age was 73.5 years and 56% (n = 66) were men. Mean time from neurological examination to surgery was 5.2 months (± 3.4–7.2), and time from decision of surgery to shunt surgery was 2.6 months (± 1.4–3.6). The majority got the same model of an adjustable shunt (n = 93). Hypertension (64%), cardiovascular disease (29%), and diabetes (23%) were the most common comorbidities. Spinal stenosis, that can affect gait and balance, occurred in only 6% of the patients.

Gait

The 10MWT was initially evaluated at Karolinska University Hospital in spring 2016; therefore, 22 of the 118 patients were excluded. Additionally, five patients were not able to complete the test pre and/or post surgery and for one patient data were missing. In total, 90 patients remained for analysis. A statistically significant increase (p < 0.0001) was seen in median walking speed that improved with 25%, from 0.72 m/s (0.54–0.935) to 0.9 m/s (0.68.9–1.05), and the number of steps decreased significantly (p < 0.0001) from 23 steps (19–30) to 20 steps (17–24), see Table 2. Forty-eight patients (53.3%) improved their walking speed with more than 0.1 m/s, and 71 patients (78.9%) walked with fewer steps postoperatively.

Table 2.

Distribution of EQ-5D-5L dimension responses pre and 3 months post surgery

| Dimension | Preoperative | Postoperative | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Mobility | m < 0.0001 | ||

| No problems | 6 (9.5%) | 20 (31%) | |

| Slight problems | 15 (23.5%) | 17 (26.5%) | |

| Moderate problems | 25 (39%) | 26 (40.5%) | |

| Severe problems | 18 (28%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Unable to walk about | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Self-care | 0.0019 | ||

| No problems | 33 (52%) | 47 (73.5%) | |

| Slight problems | 17 (26.5%) | 10 (15.5%) | |

| Moderate problems | 9 (14%) | 6 (9.5%) | |

| Severe problems | 4 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unable to wash or dress | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Usual activities | 0.0035 | ||

| No problems | 15 (23%) | 19 (29.5%) | |

| Slight problems | 16 (25%) | 23 (36%) | |

| Moderate problems | 12 (19%) | 14 (22%) | |

| Severe problems | 13 (20%) | 6 (9.5%) | |

| Unable to do usual activities | 8 (13%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Pain/discomfort | 0.402 | ||

| No pain/discomfort | 19 (30%) | 22 (34.5%) | |

| Slight pain/discomfort | 19 (30%) | 15 (23.5%) | |

| Moderate pain/discomfort | 22 (34%) | 23 (36%) | |

| Severe pain/discomfort | 3 (4.5%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Extreme pain/discomfort | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Anxiety/depression | 0.0037 | ||

| Not anxious/depressed | 22 (34.5%) | 27 (42%) | |

| Slightly anxious/depressed | 22 (34.5%) | 25 (39%) | |

| Moderately anxious/depressed | 14 (22%) | 10 (15.5%) | |

| Severely anxious/depressed | 4 (6%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Extremely anxious/depressed | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

Functional gait

Six patients did not complete the test neither pre and/or post surgery. In total, 112 patients remained for data analysis.

TUG median time significantly decreased (p < 0.0001) from 19 (14.27–24.87) to 15.25 s (12.35–19.5) and for 72 (62.5%) patients, the improvement was > 2.5 s. The TUG median number of steps decreased significantly from 23 (33–19) to 21 (25–19) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The change of 10MWT, TUG, and MMSE pre and 3 months post surgery

| Test | Median (min–max) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Pre | Post | ||

| 10MWT m/s | 90 | 0.72 (0.1–1.33) | 0.9 (0.25–1.49) | < 0.0001 |

| 10MWT steps | 89 | 23 (12–99) | 20 (14–63) | < 0.0001 |

| TUG sec | 112 | 19 (7.2–187) | 15.25 (7.6–128) | < 0.0001 |

| TUG steps | 112 | 23 (12–210) | 21 (13–100) | < 0.0001 |

| MMSE | 100 | 24 (0–30) | 26 (7–30) | < 0.0001 |

10MWT 10-m walk test, TUG timed up and go, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination.

Cognitive status

Due to limited resources, 18 patients did not accomplish MMSE pre surgery, and 100 patients remained for data analysis.

Median score on MMSE increased statistically significant (p < 0.0001) from median 24 to 26 points (Table 1). A result of ≥ 24 points are to be considered as normal cognition [25].

Health-related quality of life

Due to the fact that the EQ-5D-5L version was included in the test battery at Karolinska University Hospital from February 2017, 42 patients were excluded. Data were missing for another 12 and in total, 64 patients remained for analysis.

EQ-Index increased (p = 0.00004) from median 0.684 (0.09 min–0.863 max) to 0.732 (0.343 min–1.0 max) and EQ VAS mean from 59.738 (21.428) to 68.150 (19.966) (p = 0.0026). The patients reported improved HRQoL in all individual parameters: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The greatest improvement was seen in the category mobility, and the smallest increase was seen in the category of pain/discomfort (Table 2).

Correlations

There was a significant correlation (p < 0.05) between post tap test and post shunt results of TUG (sec) (Spearman’s rho 0.764) and 10MWT (m/s) (Spearman’s rho 0.818). The results also showed that increased walking speed measured by TUG (sec) and 10MWT (m/s) correlated with a higher score on EQ VAS (p < 0.05) (Spearman’s rho − 0.255 and 0.251) but no correlation between MMSE and EQ VAS was seen.

Falls after surgery

Eighty patients (68%) had a history of falls 12 months pre surgery; there was no significant reduction of falls post surgery. Two patients had fallen post surgery but not pre surgery. Thirty-six patients (30.5%) had no falls at all.

In the non-faller group, there was a significant correlation (p < 0.05) in time and number of steps on both 10MWT and TUG (Spearman’s rho − 0.286, − 238, − 0.224, − 224), as well as a higher score on MMSE post surgery (0.210). No significant correlation was seen with EQ VAS. There was no correlation between 10MWT, TUG, MMSE, and EQ VAS in the faller group.

Discussion

In this single-center study, we demonstrated a significant improvement in gait ability, cognitive status, and HRQoL 3 months after shunt surgery due to iNPH. Our results indicated a good selection of patients for shunt treatment at Karolinska University Hospital.

Gait ability was investigated using two instruments with good reliability, validity, and responsiveness for patients with iNPH. The instruments are easy to use in a clinical practice, and the 10MWT is considered the best instrument to assess gait ability [11].

One weakness with 10MWT and TUG is their ceiling effect, i.e., for a patient with mild gait disturbance, it may be difficult to measure a clinical difference over time. The patients had, despite the shunt surgery, a slower walking speed on 10MWT and a poorer performance on TUG in comparison with the reference values for healthy elders [4, 5].

Previous studies suggests that a TUG time reduced by 2.5 s after an intervention can be considered a clinical improvement [3]. Our results showed a median difference of 3.75 s post surgery. This is in line with the results presented in other studies [2, 23].

Only a few studies have been focusing on falls of iNPH patients [19, 21]. Falls affect not only the individual but also healthcare and the society. Nikaido et al. [21], could demonstrate that postural instability improved as soon as 1 week after surgery and Larsson et al. [19], demonstrated that the decreased number of falls sustained for as long as 12 months post surgery. In our study, the postoperative observational time was only 3 months but at 12 months preoperative, and no statistical comparison was performed due to the differences in observational time.

Gait velocity and step-length have been shown to be reduced among fallers in comparison to non-fallers in patients with iNPH [21]. These results were also seen in our study. We also found a correlation between an increased functional status in the non-faller group post surgery. This suggests that an improvement in both gait- and cognitive status may lead to a decreased risk of falling. In contradiction, Takeuchi and Yajima showed an increased risk of falls in the first 6 months post shunt surgery, even if there was an improvement in both gait and cognitive function [24].

Cognitive status improved assessed by the MMSE post surgery. MMSE is frequently used to assess cognitive function in iNPH [18, 20]. We did not exclude patients due to dementia as no patients was excluded from shunt surgery due to low cognitive function. The study sample would then be more representative for patients with iNPH.

The patients’ median value on the EQ-index improved from 0.684 pre surgery to 0.732 post surgery. The patients improved in all five parameters: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The greatest improvement was seen in the category mobility, and the least alteration was in the category pain/discomfort. This is in line with the findings by Hülser et al. [13], despite the fact that our study group walked faster in 10MWT pre surgery, but the percentage of the improvement was equal in both studies. Our study aimed on a 3-month follow-up. Larsson et al. demonstrated an increased HRQoL 12 months after shunt surgery. With a longer follow-up time period. we might have captured further improvement, but this was not the focus of this study.

The INPH patients had an overall lower HRQoL in all subcategories than the general elderly population [9, 12]. This may be due to the fact that many iNPH patients also suffer from long-term comorbidities and limited social interaction due to the classical iNPH symptoms.

We found a correlation between increased functional gait and gait ability and a higher estimated quality of life (EQ VAS). Increased mobility may lead to less dependence to other people which in turn is connected to decreased risk of depression and therefore a higher quality of life [15].

Surprisingly, no correlation was found between MMSE and EQ VAS. Even through the patient increased their cognitive status post surgery, they did not estimate an increased quality of life. Since no patients with dementia were excluded as in other studies [14, 15], it is a possibility that patients post surgery are more aware of their situation, and therefore grade themselves lower in EQ-5D-5L.

These results may be due to disability to understand the questions pre surgery or not the accurate measuring instrument for iNPH patients.

Future studies would focus on pre- and postoperative effects of physical training that is specifically developed for patients with iNPH.

This is a single-center study; no examiner was blinded, giving room for bias. However, the test process was standardized, the surgery was performed by a small group of trained neurosurgeons, and the tests were performed by qualified clinicians specialized in evaluating patients with iNPH.

The clinical awareness of iNPH has risen, and the number of shunt surgeries has increased, and our experience is that patients are diagnosed and treated earlier than before. We conclude that the clinical evaluation used at Karolinska University Hospital well discriminates for positive results of shunt surgery.

Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate shunt surgery for patients with iNPH at Karolinska University Hospital. The results showed, in line with previous studies, an improvement in gait ability. A positive significant correlation was seen between a higher self-estimated quality of life and walking ability but not between self-estimated quality of life and increased cognitive function.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily life

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EQ-5D-5L

The 5-level EQ-5D version

- EQ-Index

EQ-5D-5L crosswalk index value

- EQ VAS

The EQ-5D visual analog scale

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- iNPH

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NPH

Normal pressure hydrocephalus

- TUG

Timed Up and Go test

- 10MWT

10-Meter walk test

Author contribution

C. Hallqvist: contributed with acquisition and analysis of data, and writing.

H. Grönstedt: writing, critically comment the manuscript, and drafting the study.

L. Arvidsson: writing, critically comment the manuscript, drafting the study, and writing the ethical permit.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Data availability

The original data can be requested from the Swedish Hydrocephalus Quality Registry and patient journals.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Before undergoing shunt surgery, the patients were informed about their inclusion in the registry and that they could drop out at any time. The study was approved by the Regional ethical review board in Stockholm, DNR 2019–00353.

Consent for publication

N/A

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on CSF Circulation.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adams RD, Fisher CM, Hakim S, Ojemann RG, Sweet WH. Symptomatic occult hydrocephalus with normal cerebrospinal-fluid pressure. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:117–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196507152730301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agerskov S, Hellström P, Andrén K, Kollén L, Wikkelsö C, Tullberg M. The phenotype of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus—a single-center study of 429 patients. J Neurol Sci. 2018;391:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baltateanu D, Ciobanu I, Berteanu M. The effects of ventriculoperitoneal shunt on gait performance. J Med Life. 2019;12:194–198. doi: 10.25122/jml-2019-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20–79 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26:15–19. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohannon RW. Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2006;29:64–68. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eide PK, Pripp AH. Increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus patients compared to a population-based cohort from the HUNT3 survey. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014;11:1–6. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y-S, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF, Buchholz I. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2021;30:647–673. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Gordillo MA, Adsuar JC, Olivares PR. Normative values of EQ-5D-5L: in a Spanish representative population sample from Spanish Health Survey, 2011. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1313–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavrilov GV, Gaydar BV, Svistov DV, Korovin AE, Samarcev IN, Churilov LP, Tovpeko DV. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (Hakim-Adams syndrome): clinical symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31:737–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham JE, Ostir GV, Fisher SR, Ottenbacher KJ. Assessing walking speed in clinical research: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14:552–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grochtdreis T, Dams J, König H-H, Konnopka A. Health-related quality of life measured with the EQ-5D-5L: estimation of normative index values based on a representative German population sample and value set. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20:933–944. doi: 10.1007/s10198-019-01054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hülser M, Spielmann H, Oertel J, Sippl C. Motor skills, cognitive impairment, and quality of life in normal pressure hydrocephalus: early effects of shunt placement. Acta Neurochir. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s00701-022-05149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israelsson H, Eklund A, Malm J. Cerebrospinal fluid shunting improves long-term quality of life in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2020;86:574–582. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israelsson H, Larsson J, Eklund A, Malm J. Risk factors, comorbidities, quality of life, and complications after surgery in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: review of the INPH-CRasH study. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;49:E8. doi: 10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaraj D, Wikkelsø C, Rabiei K, Marlow T, Jensen C, Östling S, Skoog I. Mortality and risk of dementia in normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a population study. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junkkari A, Sintonen H, Nerg O, Koivisto AM, Roine RP, Viinamäki H, Soininen H, Jääskeläinen JE, Leinonen V. Health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:1391–1399. doi: 10.1111/ene.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krahulik D, Vaverka M, Hrabalek L, Hampl M, Halaj M, Jablonsky J, Langova K. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt in treating of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus-single-center study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00701-019-04135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson J, Israelsson H, Eklund A, Lundin-Olsson L, Malm J. Falls and fear of falling in shunted idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus-the idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus comorbidity and risk factors associated with hydrocephalus study. Neurosurgery. 2021;89:122–128. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyab094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu A, Sankey EW, Jusué-Torres I, Patel MA, Elder BD, Goodwin CR, Hoffberger J, Lu J, Rigamonti D. Clinical outcomes after ventriculoatrial shunting for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;143:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido Y, Urakami H, Akisue T, Okada Y, Katsuta N, Kawami Y, Ikeji T, Kuroda K, Hinoshita T, Ohno H, Kajimoto Y, Saura R. Associations among falls, gait variability, and balance function in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;183:105385. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pujari S, Kharkar S, Metellus P, Shuck J, Williams MA, Rigamonti D. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: long-term outcome after shunt surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1282–1286. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.123620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeuchi T, Yajima K. Long-term 4 years follow-up study of 482 patients who underwent shunting for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus -course of symptoms and shunt efficacy rates compared by age group- Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2019;59:281–286. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2018-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torsnes L, Blåfjelldal V, Poulsen FR. Treatment and clinical outcome in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus–a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2014;61:A4911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaccaria V, Bacigalupo I, Gervasi G, Canevelli M, Corbo M, Vanacore N, Lacorte E. A systematic review on the epidemiology of normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;141:101–114. doi: 10.1111/ane.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data can be requested from the Swedish Hydrocephalus Quality Registry and patient journals.