Abstract

Background

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway plays an important role in response to viral infection. The aim of this study was to explore the function and mechanism of MAPK signaling pathway in enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection of human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells.

Methods

Apoptosis of RD cells was observed using annexin V-FITC/PI binding assay under a fluorescence microscope. Cellular RNA was extracted and transcribed to cDNA. The expressions of 56 genes of MAPK signaling pathway in EV71-infected RD cells at 8 h and 20 h after infection were analyzed by PCR array. The levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and TNF-α in the supernatant of RD cells infected with EV71 at different time points were measured by ELISA.

Results

The viability of RD cells decreased obviously within 48 h after EV71 infection. Compared with the control group, EV71 infection resulted in the significantly enhanced releases of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α from infected RD cells (p < 0.05). At 8 h after infection, the expressions of c-Jun, c-Fos, IFN-β, MEKK1, MLK3 and NIK genes in EV71-infected RD cells were up-regulated by 2.08–6.12-fold, whereas other 19 genes (e.g. AKT1, AKT2, E2F1, IKK and NF-κB1) exhibited down-regulation. However, at 20 h after infection, those MAPK signaling molecules including MEKK1, ASK1, MLK2, MLK3, NIK, MEK1, MEK2, MEK4, MEK7, ERK1, JNK1 and JNK2 were up-regulated. In addition, the expressions of AKT2, ELK1, c-Jun, c-Fos, NF-κB p65, PI3K and STAT1 were also increased.

Conclusion

EV71 infection induces the differential gene expressions of MAPK signaling pathway such as ERK, JNK and PI3K/AKT in RD cells, which may be associated with the secretions of inflammatory cytokines and host cell apoptosis.

Keywords: Enterovirus 71, Rhabdomyosarcoma cells, MAPK, PCR array

Introduction

Human enterovirus belongs to the RNA virus family Picornaviridae which includes polioviruses, type A coxsackieviruses, type B coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and enterovirus types 68–71. Among these viruses, human EV71 and coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16) are major causative agents of hand, foot, and mouth diseases (HFMD).1 In recent years, the mortality rate of EV71 infection was significantly elevated, and there are neither approved therapies nor vaccines for EV71.2, 3 Although the underlying mechanisms remain obscure, host innate immunity is thought to play an important role in virus infection.4, 5 MAPKs are key signaling molecules in innate immunity, which are a family of serine/threonine protein kinases widely conserved in eukaryotes and involved in many cellular functions such as inflammation, cell proliferation, differentiation, movement, and death.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 To date, seven distinct MAPK groups have been characterized in mammalian cells: extracellular regulated kinases (ERK1/2), c-Jun NH2 terminal kinases (JNK1/2/3), p38 MAPK (p38 α/β/γ/δ), ERK3/4, ERK5, ERK7/8, and Nemo-like kinase (NLK).11, 12 Among these, the most extensively studied groups are ERK1/2, JNKs and p38 MAPK. Virus-infected cells induce acute reactions that not only activate MAPK signaling cascades to defend virus infection but also can be used by viruses to support viral replication.13 Previous studies have shown that influenza virus, herpes simplex virus type 2 and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) can activate MAPKs including ERK1/2 (p42/p44 MAPK), JNK, or p38 MAPK, which further increase the expressions of different cytokines or affect the growth of viruses.14, 15, 16 In addition, many genes regulated by MAPKs are dependent on NF-κB, c-Fos and c-Jun for transcription, thus activating the gene expressions of pro-inflammatory or antiviral cytokines to release IL-6, IFN-β and TNF-α.17, 18 In this study, we employed PCR array to explore the differential gene expressions of MAPK signaling pathway proteins in EV71-infected RD cells, and demonstrated that the releases of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α may be associated with the activation of ERK, JNK and PI3K/AKT.

Materials and methods

Virus preparation and plaque assay

RD cells were purchased from CBTCCCAS (Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection) and cultured in high glucose DMEM (Thermo Scientific HyClone, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2 atmosphere. EV71 strain CCTCC/GDV083 (ATCC VR-784) (China Center for Type Culture Collection, CCTCC) was propagated using RD cells. Once 90% of the cells showed cytopathic effect (CPE), the viral supernatants were gathered and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The clear supernatant was then transferred to a new tube, and the debris was frozen and thawed three times before centrifugation. Finally, the supernatants were pooled and stored at −70 °C. RD cells (4 × 105 cells per well) were seeded into a six-well culture plate overnight and then infected with a 10-fold serially diluted virus suspension. One hour after infection, the cells were washed once with PBS and overlaid with 0.3% agarose in DMEM containing 2% FBS. After 96 h incubation, the cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and then stained with 1% crystal violet solution. The virus titers were determined by plaque assays using RD cells in triplicate.

EV71 infection and viability of RD cells

One batch of uninfected RD cells in 25 cm2 culture flask were used as the control, while two other batches of RD cells were infected with UV-inactivated EV71 strain and alive EV71 strain at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 in 4 mL of virus inoculum diluted with maintenance medium. Approximately 1 × 106 cells were incubated with EV71 at an MOI of 5 or as indicated and allowed to absorb for 2 h at 37 °C. Unbound viruses were removed by washing the cells with medium, and 15 mL of maintenance medium was added. Infected cells and culture supernatants were collected at different time intervals. The viability of RD cells was assayed using trypan blue exclusion method.

Evaluation of apoptosis in RD cells by annexin V-FITC/PI binding assay

RD cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells onto pre-treated coverslips in a 6-well plate. After incubation at 37 °C overnight, the cells were inoculated at an MOI of 5 with EV71 strain and UV-inactivated EV71 strain for 2 h. After absorption, the inoculum was removed, and replaced with 3 mL of maintenance medium. The cells were subjected to incubation for another 8 h, and then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. The coverslips were stained by annexin V-FITC/PI (Major BioTech, Shanghai, China) and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Detection of cytokines by ELISA

Culture supernatants were collected at 0 h, 20 h and 32 h after EV71 infection (MOI = 5), including uninfected control and mock-infected control, and then stored at −70 °C until use. ELISA kits for IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α were purchased from Westang Biotechnology (Shanghai, China) and the ELISA assay was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Spectrometric absorbance at wavelength of 450 nm was measured on an enzyme immunoassay analyzer (Model 680, Bio-Rad, USA). All assays were performed in triplicate.

RNA isolation and PCR array

After incubation at 37 °C for 8 h and 20 h, both uninfected and infected RD cells (MOI = 5) were harvested for the extraction of total RNA. RNA was extracted from RD cells with SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using RT-PCR Kit (CT biosciences; catalog# CTB101, China) and then run on the ABI 9700 thermocycler (ABI, Foster City, CA). A total of 56 kinds of primers including p38 MAPK, JNK, ERK and NF-κB were designed according to gene sequences published in GenBank. Gene-specific primers for B2M, ACTB, GAPDH, RPL27, HPRT1 and OAZ1, as well as a PCR positive control and a genomic DNA control were fixed in 96-well PCR plate. PCR were performed with customized PCR arrays containing pre-dispensed primer assays (CT biosciences, China) on the LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using SYBR MasterMix (CT biosciences; catalog# CTB103, China). Each PCR contained cDNA synthesized from 10 ng of total RNA. The PCR amplification parameters were 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 20 s. Two PCR arrays for EV71-infected RD cells and uninfected RD cell control were used for relative quantification of gene expression. This experiment was repeated three times. Fold change was calculated using the formula of 2-ΔΔCt.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical analyses were preformed using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). The three groups were compared using two-way ANOVA. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Growth characteristics of EV71-infected RD cells

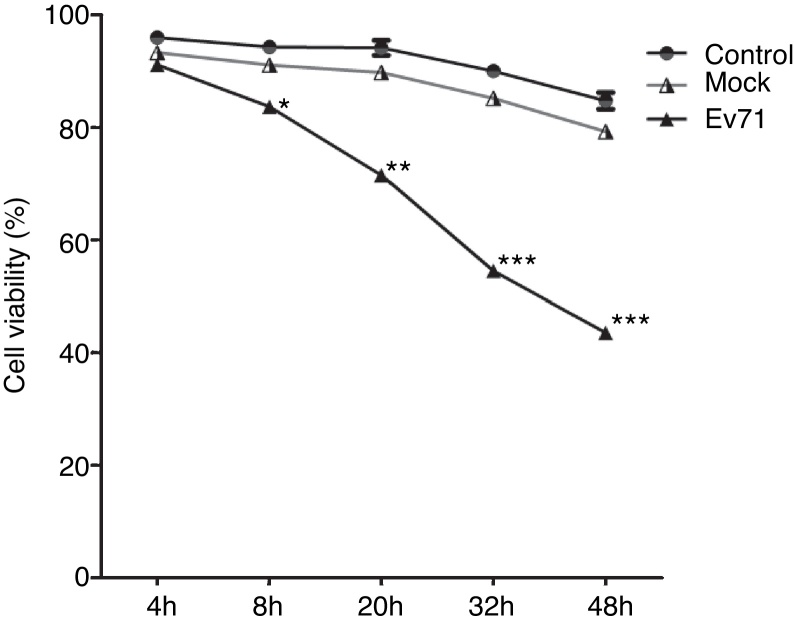

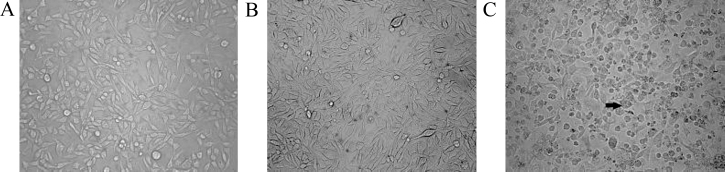

Two batches of RD cells with three experimental models in each group including uninfected RD cells (Control), UV-inactivated EV71-infected RD cells (Mock), and EV71-infected RD cells (EV71) were analyzed at 4 h, 8 h, 20 h, 32 h and 48 h after infection. In uninfected control and mock-infected control, the growth of the cells did not exhibit an obvious difference at 4 h and 8 h. However, the viable EV71-infected cells exhibited a significant decrease in growth at 20 h, 32 h and 48 h (Fig. 1). Visible CPE was also observed in the infected cell culture (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

EV71 infection induced RD cell apoptosis. The viability of uninfected RD cells (Control), UV-inactivated EV71-infected RD cells (Mock), and EV71-infected RD cells (EV71) were determined at designated time points after EV71 infection by trypan blue exclusion technique. The data were expressed as mean ± SE from three independent experiments and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

The CPE of EV71-infected RD cells. (A) Uninfected RD cells; (B) UV-inactivated EV71-infected RD cells; (C) EV71-infected RD cells at 32 h. Cell morphology was examined by a light microscope (400×). Apoptotic cell was labeled by black arrows.

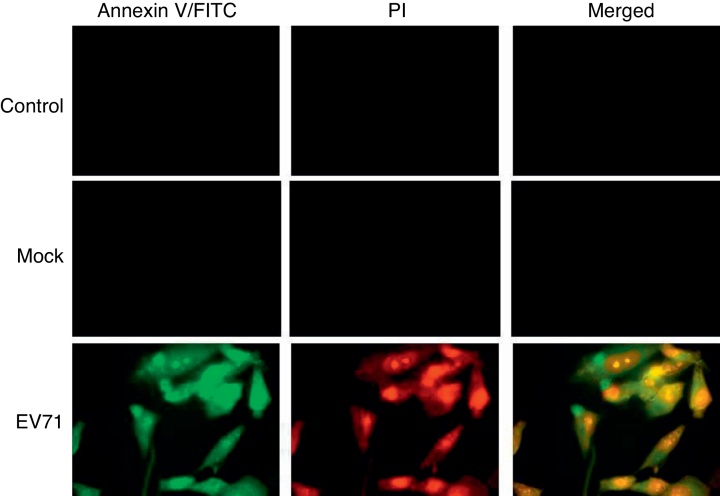

Annexin V-FITC/PI fluorescent analysis of EV71-infected RD cells

The phosphatidylserine (PS) was localized mainly on the membrane surface of cytoplasmic cells. However, PS could be translocated to the outer leaflet of the membrane during apoptosis. Staining cells with annexin V-FITC allowed for the detection of PS exposure as an early indicator of apoptosis. When RD cells were infected with EV71 at 8 h, the cells were stained with annexin V-FITC/PI and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

EV71-induced apoptosis in RD cells. Control: uninfected RD cells; Mock: UV-inactivated EV71-infected RD cells. EV71: EV71-infected RD cells. Early membrane revealed an obvious change associated with apoptosis in EV71-infected RD cells. The exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) was analyzed using FITC-labeled annexin V. Cell death was assessed with propidium iodide (PI). EV71-infected RD cells were harvested and stained with annexin V-FITC/PI at 8 h after infection, and then examined under a fluorescence microscope (1000×).

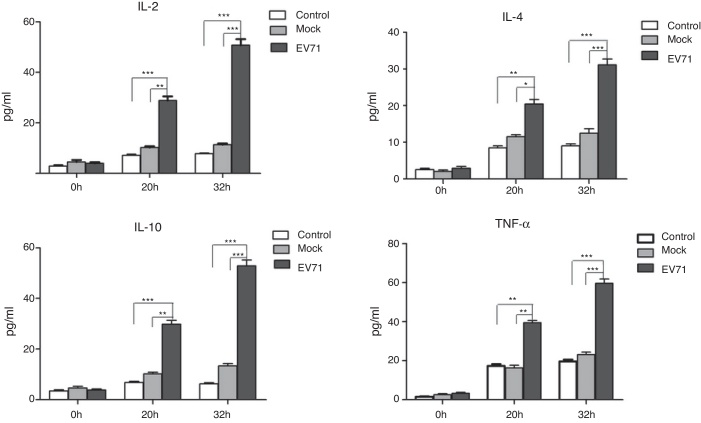

EV71 infection increased the release of cytokines in RD cells

Culture supernatants were harvested from the control, mock-infected or EV71-infected RD cells at 0 h, 20 h and 32 h after infection, and the levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α were measured by ELISA. Once RD cells were infected by EV71, the obviously increased secretion of cytokines such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α was observed (Fig. 4). Meanwhile, a significant difference among three groups was also observed.

Fig. 4.

Cytokine production in EV71-infected RD cells. RD cells were infected with EV71 (MOI = 5). At 0 h, 20 h and 32 h, cell culture supernatants were collected and the levels of cytokines were performed by ELISA. The data were expressed as mean ± SE from three independent experiments and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

EV71 infection induced differential gene expressions of MAPK signaling pathway

Eight hours after RD cells were infected with EV71, the expression levels of c-Jun, c-Fos, IFN-β, MEKK1 (MAP3K1), MLK3 (MAP3K11) and NIK (MAP3K14) revealed 2.08–6.12 fold enhancement, while other 19 genes (e.g. AKT1, AKT2, E2F1, IKK and NF-κB1) exhibited down-regulation. However, at 20 h after infection, AKT2, ELK1, c-Jun, c-Fos, NF-κB p65, PI3K and STAT1 in EV71-infected RD cells were up-regulated and exhibited 2.19–5.52 fold enhancement in expression. Meanwhile, MAPK signaling pathway molecules including MEKK1, ASK1 (MAP3K5), MLK2 (MAP3K10), MLK3, NIK, MEK1 (MAP2K1), MEK2 (MAP2K2), MEK4 (MAP2K4), MEK7 (MAP2K7), ERK1 (MAPK3), JNK1 (MAPK8) and JNK2 (MAPK9) were significantly up-regulated and revealed 2.00–4.09 fold increases in expression level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differential gene expressions of MAPK signaling pathway in RD cells in response to EV71 infection at 8 h and 20 h postinfection.

| Symbols | Description of genes | EV71/control (fold changes) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 h | 20 h | ||

| Akt1 | V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (AKT1) | −9.89 | −1.13 |

| Akt2 | V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 (AKT2) | −3.36 | 2.66 |

| Akt3 | V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 3 (AKT3) | −1.06 | 1.58 |

| c-Fos | c-fos proto-oncogene | 3.34 | 3.23 |

| c-Jun | c-Jun proto-oncogene | 3.19 | 5.52 |

| E2F1 | Transcription factor E2F1 (RBAP1; RBBP3; RBP3) | −3.99 | −1.17 |

| E2F2 | Transcription factor E2F2 | −1.64 | 1.55 |

| ELK1 | E twenty-six (ETS)-like transcription factor 1 | 1.19 | 2.19 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | −4.78 | 1.38 |

| IFN-β | Interferon beta | 5.22 | 1.47 |

| IGF1 R | Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), receptor (CD221; IGFR; JTK13) | −3.50 | 1.27 |

| IKBKB | Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta (IKK-β; IKKB) | −3.52 | 1.33 |

| IKBKG | Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit gamma (FIP3; IKK-γ; NEMO) | −5.76 | 1.40 |

| IL-1α | Interleukin-1 alpha | −2.60 | 1.64 |

| IL-1β | In Interleukin-1 beta | −2.20 | 1.30 |

| IL-2 | Interleukin 2 | 1.24 | 12.15 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin 4 | −3.72 | 2.39 |

| IL-6R | Interleukin 6 receptor (CD126) | −5.80 | 1.92 |

| IL-7 | Interleukin 7 | −1.65 | 1.26 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 | 1.10 | 12.15 |

| IRAK1 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | −3.70 | 3.39 |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 (JTK10; THCYT3) | 1.06 | −1.21 |

| MADD | MAP-kinase activating death domain | 1.57 | 1.82 |

| MAP3K1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK 1; MAPKKK 1; SRXY6) | 2.08 | 2.25 |

| MAP3K5 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5 (ASK1; MAPKKK5; MEKK5) | 1.30 | 2.00 |

| MAP3K7 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 (MEKK7; MAPKKK 7;TAK1) | −1.13 | 1.14 |

| MAP3K10 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 10 (MLK2) | 1.48 | 4.07 |

| MAP3K11 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 11 (MEKK11; MLK3; PTK1) | 2.61 | 3.85 |

| MAP3K14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 14 (MEKK14, NIK) | 6.12 | 4.09 |

| MAP2K1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAPKK1; MEK1) | 1.30 | 2.46 |

| MAP2K2 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 2 (MAPKK2; MEK2) | −1.31 | 2.18 |

| MAP2K3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 (MAPKK3; MEK3) | −2.29 | −1.10 |

| MAP2K4 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (JNKK1; MAPKK4; MEK4) | −1.06 | 2.54 |

| MAP2K6 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 (MAPKK6; MEK6) | 1.58 | −1.23 |

| MAP2K7 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MAPKK7; MEK7) | −1.09 | 3.05 |

| MAPK1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (ERK2; MAPK2; P42-MAPK) | 1.20 | 1.00 |

| MAPK3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (ERK1; P44-MAPK) | 1.67 | 3.95 |

| MAPK8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (JNK; JNK1; SAPK1) | 1.73 | 2.53 |

| MAPK9 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 (JNK2; JNK2A; JNK2B; SAPK) | 1.02 | 2.25 |

| MAPK10 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 (JNK3; SAPK1b) | 1.56 | 1.30 |

| MAPK11 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 11 (p38-β MAPK) | 1.80 | 1.01 |

| MAPK12 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 12 (p38-γ MAPK, ERK6) | 1.13 | −1.00 |

| MAPK13 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 13 (p38-δ MAPK, SAPK4) | 1.52 | −1.34 |

| MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (p38-α MAPK) | 1.15 | −1.19 |

| NF-κB1 | Nuclear factor NF-kappa-B p105 subunit (NF-kB1; NF-κB-p105; NF-κB-p50) | −4.81 | 1.18 |

| NF-κB3 | Nuclear factor NF-kappa-B p65 (RELA; NF-κB p65) | −1.35 | 2.63 |

| PI3Kα | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, alpha polypeptide (PI3K; p110-alpha) | −1.26 | 1.04 |

| PI3Kγ | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma isoform (PI3CG; PI3K; PI3Kgamma) | −1.40 | 5.18 |

| PIK3R2 | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit beta (P85B; p85; p85-BETA) | −2.12 | −1.20 |

| PPP3R1 | Protein phosphatase 2B regulatory subunit 1 (CALNB1; CNB1) | −1.52 | 1.94 |

| RIPK1 | Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIP; RIP1) | −2.44 | 1.24 |

| STAT1 | Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (CANDF7; ISGF-3; STAT91) | −6.18 | 4.04 |

| STAT5A | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A | −1.14 | −1.15 |

| STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B | −3.17 | 1.08 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 (DPD1; LAP; TGFbeta) | −2.23 | −1.15 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factors | −1.97 | 2.19 |

Negative values indicate down-regulation of genes.

Discussion

MAPKs are a heterogeneous group of enzymes responsible for phosphorylating serine and threonine in many proteins.19, 20 In mammals, three major MAPK signaling pathways have been identified as ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK.21, 22 MAPKs are phosphorylated and activated by MAPK-kinases (MAPKKs or MAP2Ks), which in turn are phosphorylated and activated by MAPKK-kinases (MAPKKK or MAP3Ks).23 As previously reported, many viruses including HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) can target MAPK pathways as a means to manipulate cellular function and to control viral infection and replication.24, 25, 26 In this study, MAPK signaling pathway molecules, including MEKK1, ASK1, MLK, NIK, MEK1/2, MEK4/7, ERK and JNK were significantly up-regulated in EV71-infected RD cells, which stimulated and induced the immune response of RD cells.

ERK was the first MAPK to be identified as the best studied mammalian MAPK pathway.27 ERK1 and ERK2 are two isoforms with 83% amino acid homology. Both isoforms are expressed in various tissues, and can be activated by a large number of extracellular and intracellular stimuli.28 Activated Raf (or other MAP3K) binds and phosphorylates downstream kinase MEK1 and MEK2 with dual specificity, which in turn phosphorylate ERK1/2.29 In this study, the expressions of MEK1, MEK2 and ERK1 genes were significantly up-regulated and revealed 2.46-, 2.18- and 3.95-fold enhancement after EV71 infection, which may be associated with the activation of downstream molecules such as NF-κB p65, ELK-1, c-Fos, c-Jun and STAT1. Whereas, STAT1 is a member of signal transducers and activators in transcription family, and involved in the up-regulation of the genes through type I, type II or type III interferon.30, 31 Both NF-κB and STAT1 are rapidly activated in response to various stimuli including viral infection and cytokines, thus controlling the expression of anti-apoptotic, pro-proliferative and immune response genes.32 PCR array showed that the expressions of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α exhibited the enhancement by 12.15-, 2.39-, 12.15- and 2.19-fold at 20 h after infection. Compared with control and inactive EV71-infected Mock, the levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α at 20 h and 32 h after infection showed significant increases in EV71-infected RD cells (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001). The results indicated that EV71 infection could increase the releases of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α in RD cells, as well as mediate inflammation and apoptosis.

Mammalian JNKs are encoded by three distinct genes (JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3). JNK1 and JNK2 are ubiquitously expressed, while JNK3 is restricted to brain, heart and testis tissues.33 JNK pathway is activated by a large number of external stimuli, and the initial signaling pathway starts with the activation of several MAPKKKs including TAK1, MEKK1/4, MLK-2 and -3, and ASK1, which phosphorylate MEK4 or MEK7 and induce the activation of JNK. As mentioned previously, several transcription factors are downstream proteins especially c-Fos and c-Jun activated by JNK.23 Once activated by phosphorylation, these transcription factors can induce the secretions of proinflammatory cytokines.34 In this study, the up-regulation of MEKK1, ASK1, MLK2, MLK3, NIK, MEK4 and MEK7 was observed, which may be related to the activation of JNK signaling pathway. Subsequently, transcription factors of NF-κB p65, ELK-1, c-Fos, c-Jun and STAT1 are activated, which plays a key role in regulating the immune response to viral infection and stimulates the releases of cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-β, IL-1β, IL-2 and IL-6.35 JNK is also involved in the regulation of apoptosis through the modulation of c-Jun/AP-1 and transforming growth factor-β in MDCK cells.11 Although JNK plays an important role in apoptosis, it also contributes to survival. These opposite effects could be partly due to the duration or magnitude of the pathway activation and the activation of other pro-survival pathways. Prolonged activation of JNK can mediate apoptosis, whereas transient activation can promote cell survival.36

The role of p38 MAPK in immune system has been extensively studied. The p38 MAPK participates in macrophage and neutrophil functional responses including respiratory burst activity, chemotaxis, granular exocytosis, adherence, and apoptosis, as well as mediates T cell differentiation and apoptosis by regulating the production of IFN-γ.37 In addition, p38 MAPKs can be activated by MAPKKs, MKK3 and MKK6. The activation of p38 MAPK controls the expression of RANTES, IL-8 and TNF-α, which appears to control proinflammatory responses after infection.38 In this study, PCR array did not reveal the activation of p38 MAPK signaling pathway genes including p38 MAPK α, β, γ and δ, which may be irrelevant to EV71 infection.

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway plays an important role in the growth and survival of cells. The AKT cascade is activated by receptor tyrosine kinases, cytokine receptors, G-protein coupled receptors, and other stimuli, thus inducing the accumulation of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5 triphosphates by PI3K.38, 39 Three AKT isoforms (AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3) can mediate downstream events through PI3K. As previously reported, EV71 can activate PI3K/AKT to trigger anti-apoptosis pathway at the early phase during infection.40 At 8 h after EV71 infection, the expressions of AKT1 and AKT2 were significantly down-regulated and revealed a reduction in expression level by 9.89- and 3.36-fold, while PI3Kγ and AKT2 exhibited an increase by 5.18-fold and 2.66-fold at 20 h after EV71 infection, respectively. It is postulated that differential expression of PI3K/AKT in RD cells may be attributed to different conditions such as MOI, infection time, and EV71 strain.

In summary, MAPKs are components of signaling cascades where various extracellular stimuli converge to initiate inflammation, including production of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-1, IL-2 and IL-6). The releases of most cytokines and chemokines are regulated primarily at the level of transcription via the activation of specific transcription factors controlled by NF-κB and MAPKs. Therefore, the differential gene expressions of ERK, JNK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway genes may be related to EV71 replication, proinflammatory cytokines and apoptotic responses in RD cells.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Guanghua Luo and Jingting Jiang for their help with flow cytometry and statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Frydenberg A., Starr M. Hand, foot and mouth disease. Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32:594–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon T., Lewthwaite P., Perera D., Cardosa M.J., McMinn P., Ooi M.H. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:778–790. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee B.Y., Wateska A.R., Bailey R.R., Tai J.H., Bacon K.M., Smith K.J. Forecasting the economic value of an Enterovirus 71 (EV71) vaccine. Vaccine. 2010;28:7731–7736. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawai T., Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunardi A., Gaboli M., Giorgio M., et al. A Role for PML in Innate Immunity. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:10–19. doi: 10.1177/1947601911402682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H., Hasegawa Y., Kanamaru K., Zhang J.H. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a review. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;110:133–139. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0353-1_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Affolter A., Fruth K., Brochhausen C., Schmidtmann I., Mann W.J., Brieger J. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-related kinase in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas after irradiation as part of a rescue mechanism. Head Neck. 2011;33:1448–1457. doi: 10.1002/hed.21623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dingayan L.P. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) and NADPH Oxidase (NOX) are cytoprotective determinants in the trophozoite-induced apoptosis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cell Immunol. 2011;272:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong W.R., Chen Y.Y., Yang S.M., Chen Y.L., Horng J.T. Phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK in an early entry step of enterovirus 71. Life Sci. 2005;78:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tung W.H., Hsieh H.L., Lee I.T., Yang C.M. Enterovirus 71 modulates a COX-2/PGE2/cAMP-dependent viral replication in human neuroblastoma cells: role of the c-Src/EGFR/p42/p44 MAPK/CREB signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:559–570. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing Z., Cardona C.J., Anunciacion J., Adams S., Dao N. Roles of the ERK MAPK in the regulation of proinflammatory and apoptotic responses in chicken macrophages infected with H9N2 avian influenza virus. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:343–351. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broom O.J., Widjaya B., Troelsen J., Olsen J., Nielsen O.H. Mitogen activated protein kinases: a role in inflammatory bowel disease? Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;158:272–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi O., Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui K.P.Y., Lee S.M.Y., Cheung C., et al. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in primary human macrophages by influenza A virus (H5N1) is selectively regulated by IFN regulatory factor 3 and p38 MAPK. J Immunol. 2009;182:1088–1098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin D., Feng N., Fan W., et al. Activation of PI3K/AKT and ERK MAPK signal pathways is required for the induction of lytic cycle replication of Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by herpes simplex virus type 1. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong J., Shen X., Chen C., Qiu H., Yang R. Down-regulation of HIV-1 infection by inhibition of the MAPK signaling pathway. Virol Sin. 2011;26:114–122. doi: 10.1007/s12250-011-3184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tung W.H., Hsieh H.L., Yang C.M. Enterovirus 71 induces COX-2 expression via MAPKs, NF-kappaB, and AP-1 in SK-N-SH cells: role of PGE(2) in viral replication. Cell Signal. 2010;22:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vallabhapurapu S., Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceballos-Olvera I., Chavez-Salinas S., Medina F., Ludert J.E., del Angel R.M. JNK phosphorylation, induced during dengue virus infection, is important for viral infection and requires the presence of cholesterol. Virology. 2010;396:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito G., Perrino C., Schiattarella G.G., et al. Induction of mitogen-activated protein kinases is proportional to the amount of pressure overload. Hypertension. 2010;55:137–143. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steer S.A., Moran J.M., Christmann B.S., Maggi L.B., Jr., Corbett J.A. Role of MAPK in the regulation of double-stranded RNA- and encephalomyocarditis virus-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression by macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;177:3413–3420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jafri M., Donnelly B., McNeal M., Ward R., Tiao G. MAPK signaling contributes to rotaviral-induced cholangiocyte injury and viral replication. Surgery. 2007;142:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishna M., Narang H. The complexity of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) made simple. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3525–3544. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8170-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jham B.C., Montaner S. The Kaposi's sarcoma? associated herpesvirus G protein? coupled receptor: lessons on dysregulated angiogenesis from a viral oncogene. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Q.L., Zhu S.Y., Bian Z.Q., et al. Activation of p38 MAPK pathway by hepatitis C virus E2 in cells transiently expressing DC-SIGN. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2010;56:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi J., Qin X., Zhao L., Wang G., Liu C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat induces B7-H1 expression via ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell Immunol. 2011;271:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plotnikov A., Zehorai E., Procaccia S., Seger R. The MAPK cascades: signaling components, nuclear roles and mechanisms of nuclear translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta – Mol Cell Res. 2011;1813:1619–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefloch R., Pouyssgur J., Lenormand P. Single and combined silencing of ERK1 and ERK2 reveals their positive contribution to growth signaling depending on their expression levels. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:511–527. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00800-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X., Li Q., Dowdell K., Fischer E.R., Cohen J.I. Varicella-Zoster virus ORF12 protein triggers phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and inhibits apoptosis. J Virol. 2012;86:3143–3151. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06923-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perry S.T., Buck M.D., Lada S.M., Schindler C., Shresta S. STAT2 mediates innate immunity to Dengue virus in the absence of STAT1 via the type I interferon receptor. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001297. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frieman M.B., Chen J., Morrison T.E., et al. SARS-CoV pathogenesis is regulated by a STAT1 dependent but a type I, II and III interferon receptor independent mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000849. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy D.E., Mari I.J., Durbin J.E. Induction and function of type I and III interferon in response to viral infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan F., Wang X.M., Liu Z.C., Pan C., Yuan S.B., Ma Q.M. JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3 are involved in P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das K.C., Muniyappa H. c-Jun-NH2 terminal kinase (JNK)-mediates AP-1 activation by thioredoxin: phosphorylation of cJun, JunB, and Fra-1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;337:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ting J.P.Y., Duncan J.A., Lei Y. How the noninflammasome NLRs function in the innate immune system. Sci STKE. 2010;327:286. doi: 10.1126/science.1184004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhanasekaran D.N., Reddy E.P. JNK signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:6245–6251. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Sullivan A.W., Wang J.H., Redmond H.P. The role of P38 MAPK and PKC in BLP induced TNF-[alpha] release, apoptosis, and NF [kappa] B activation in THP-1 monocyte cells. J Surg Res. 2009;151:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medders K.E., Kaul M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 in HIV infection and associated brain injury. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:202–215. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9260-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Florentin J., Dental C., Firaguay G., et al. Highjacking of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by Hepatitis C virus in TLR9-activated human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Retrovirology. 2010;7:P7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu M.J., Wu C.Y., Chiang H.H., Lai Y.L., Hung S.L. PI3K/Akt signaling mediated apoptosis blockage and viral gene expression in oral epithelial cells during herpes simplex virus infection. Virus Res. 2010;153:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]