Abstract

Purpose

Sperm chromosomal abnormalities impact male fertility and pregnancy outcomes. However, the proportion of sperm with chromosomal abnormalities in normozoospermic men remains unclear. Herein, we evaluated sperm aneuploidy for 23 chromosomes to elucidate its incidence in normozoospermic men.

Methods

Sperm from ten normozoospermic donors were obtained from a human sperm bank and analyzed using fluorescence in situ hybridization. The frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, and diploidy were analyzed along with trisomy, triploidy, tetraploidy, and other numerical abnormalities per chromosome and per donor levels.

Results

A total of 248,811 sperm cells were analyzed (average: 24,881 ± 381 cells/donor), of which 246, 658 were haploid, 818 nullisomic, 393 disomic, 894 diploid, 13 triploid, 8 tetraploid, 3 trisomic, and 24 harbored multiple aneuploidies. Among the 22 autosomal and 2 sex chromosomes, the mean frequency of aneuploidy per chromosome was 0.49 ± 0.16%, including 0.33 ± 0.16% for nullisomy and 0.16 ± 0.08% for disomy. The mean frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, and aneuploidy per donor were 0.33 ± 0.13%, 0.16 ± 0.05%, and 0.49 ± 0.13%, respectively. The total frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and aneuploidy per donor were 7.62 ± 3.06%, 3.63 ± 1.12%, 0.36 ± 0.15%, and 11.25 ± 3.05%, respectively.

Conclusions

The dominant chromosome numerical abnormalities in normozoospermic men are nullisomy, disomy, and diploidy. Generally, the frequency of nullisomy is higher than that of disomy. The disomy or nullisomy frequencies for each chromosome being gained or lost were not unified and varied; some chromosomes (e.g., chromosomes 21 and 22 and sex chromosomes) are more prone to disomy while some others (e.g., chromosome 3) are more prone to nullisomy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-022-02536-7.

Keywords: Normozoospermic donor, Male infertility, Sperm, Fluorescence in situ hybridization, Aneuploidy, Nullisomy

Introduction

Aneuploidy involves the gain or loss of one or more of the 24 chromosomes, which affects 0.3% of newborns and is observed in 4% of stillbirth cases as well as 35% of clinically recognized spontaneous abortions [1, 2]. Additionally, aneuploidy accounts for up to 60% of early pregnancy loss in humans [3–5]. The resulting quantitative change in genes from certain chromosomes disturbs embryonic development, thereby resulting in most embryos being unable to survive through the early developmental stages. Embryos with extra chromosomes of 13, 18, 21, X, and Y might be viable and develop to later stages or even up to live birth; however, such cases are often accompanied by severe developmental disorders, multiple malformations, intellectual disability, and cognitive impairment [6]. Previous studies have suggested that embryonic chromosomal abnormalities can result from meiotic errors in germ cells and mitotic errors in zygotes [7–9]. It is important to assess the proportion of sperm or oocytes with an abnormal chromosome number, as these indexes are directly related to the production of embryos with chromosomal abnormalities.

Prior to the introduction of the human sperm–hamster egg system in the 1980s, information on human germ-cell chromosomes obtained through indirect means had been limited [10]. This system allows for the direct analysis of spermatozoon karyotype under a microscope; however, the technique is rather complex, requiring hamster egg collection, co-incubation of hamster egg and human sperm, and sperm fusion with hamster egg. Moreover, given their low penetration and fusion rate, metaphase chromosomes are difficult to obtain, and the respective bands are often ambiguous during analysis [11, 12]. In the 1990s, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology was first described and introduced for evaluating sperm chromosome numerical abnormalities. FISH has many advantages, including interphase detection without the need for cell culture to obtain metaphase chromosomes, improved statistical power due to the availability of a larger number of interphase cells compared to those of metaphase cells in the human sperm–hamster egg system, high sensitivity and specificity through chromosome-specific nucleotide-sequence probes, and convenience in the detection of changes in chromosome count based on fluorescent signals, which altogether enable improved chromosome number detection [13–16].

Although normozoospermic males produce a certain fraction of aneuploid sperm, there is limited knowledge regarding the aneuploidy levels of all 23 chromosomes in the sperm cells of normozoospermic males. Templado et al. [17] analyzed healthy donor data from 30 studies that focused on sperm aneuploidy assessment and found that most studies selected a handful of chromosomes for analysis (most often chromosomes 13, 18, 21, and the sex chromosomes). In contrast, the remaining chromosomes were rarely studied, while the total number of chromosomes analyzed in the 30 studies added up to 18 chromosomes [17]. This might be attributed to the fact that FISH cannot simultaneously detect all 23 chromosomes in a single sperm nucleus owing to the limited number of fluorescent molecules, the limited space within the sperm making signals superimposed and difficult to analyze, and the expensive cost of probes for detecting all 23 chromosomes. Furthermore, aneuploidy rates for the 18 chromosomes in human sperm reportedly range from 0.03% (chromosome 8) to 0.47% (chromosome 22) [17], suggesting that the incidence of sperm aneuploidy is low and requires a large number of sperm to be analyzed for its detection. This would impose a considerable research workload and represents a major reason for most studies focusing on a few specific chromosomes that allow an embryo to survive when trisomy occurs. However, the more chromosomes analyzed, the more information can be obtained to determine the overall incidence of aneuploidy in men with normozoospermia.

Therefore, in this study, we examine the proportion of spermatozoa with numerical abnormalities in all 23 chromosomes to gain a comprehensive understanding of the frequency and range of variation for all chromosomal numerical abnormalities in the sperm of normozoospermic males.

Materials and methods

Donors

Ten normozoospermic donors (age: 25–39 years; mean: 30.7 ± 4.7 years) who met the sperm-donation criteria were recruited from the human sperm bank of Fudan University. Among the ten donors, five had children, while the remaining five did not, one of which had donated sperm twice and the recipients had frozen the embryos, and the other four were being selected by recipients. All donors presented normal semen parameters, including sperm concentration, progressive motility, and morphology, according to the fifth edition of World Health Organization standards. The semen parameters of the ten donors are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Semen parameters of ten donors

| Donor no | Age (y) | Volume (mL) | Concentration (106/mL) | Motility (%) | Normal morphology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 2 | 164 | 62 | > 4 |

| 2 | 29 | 3.5 | 109 | 60 | > 4 |

| 3 | 28 | 3 | 76 | 62 | > 4 |

| 4 | 36 | 4.7 | 76 | 64 | > 4 |

| 5 | 25 | 6.7 | 70 | 60 | > 4 |

| 6 | 25 | 3 | 150 | 60 | > 4 |

| 7 | 37 | 2.5 | 111 | 60 | > 4 |

| 8 | 39 | 4.7 | 79 | 61 | > 4 |

| 9 | 29 | 2.7 | 68 | 62 | > 4 |

| 10 | 29 | 2.5 | 60 | 63 | > 4 |

| Mean ± SD | 30.7 ± 4.7 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 96.3 ± 34.3 | 61.4 ± 1.4 | — |

| WHO reference values | — | 1.5 | 15 | 40 | 4 |

WHO reference values refer to the fifth edition of the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, 2010

SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization

Ethical approval

All participants underwent genetic counseling and provided informed consent regarding donation and the purpose of the sperm aneuploidy study program. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Shanghai JiAi Genetics & IVF Institute (JIAI E2018-23) and the Human Sperm Bank of Fudan University (HSBOFU2021-01).

Semen preparation

Semen was collected after 3 days of abstinence, rinsed three times in 1 × Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then centrifuged for 8 min at 300 × g. The pellet was resuspended in a 3:1 fixative solution of methanol and glacial acetic acid, after which sperm cells were transferred onto slides and digested in 1 N NaOH at room temperature for 2 min to decondense highly compacted sperm chromatin [18]. The slides were then dehydrated into a 70%, 85%, and 100% ethanol series for 1 min each and air dried.

FISH protocol

A probe mix solution was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). For each donor, 22 rounds of FISH were performed separately on 22 slides with corresponding triple or dual colored probe mix to assess 22 autosomal chromosomes with approximately 1000 sperm nuclei scored for each chromosome. The triple hybridization probe sets consisted of (1) one chromosome 1–3 centromeric probes (locus D1Z1, D2Z1 or D3Z1, Spectrum Orange; Vysis Inc.) plus chromosome X (locus DXZ1, Spectrum Green; Vysis Inc.) and chromosome Y (locus DYZ1, Spectrum Aqua; Vysis Inc.) centromeric probes; (2) one chromosome 4, 6–11, and 16–18 centromeric probes (4, 6–11, and 16–18 centromeric probes, Spectrum Aqua; Vysis Inc) plus chromosome X (locus DXZ1, Spectrum Green; Vysis Inc.) and chromosome Y (locus DYZ3, Spectrum Orange; Vysis Inc.) centromeric probes. The dual hybridization probe sets consisted of (1) chromosome 12 centromeric probe (locus D12Z1, Spectrum Green; Vysis Inc.) plus chromosome 18 centromeric probe (locus D18Z1, Spectrum Aqua; Vysis Inc.); (2) one chromosome 5, 14–15, 19–20, and 22 sub telomeric DNA probes (5, 14–15, 19–20, and 22 sub telomeric DNA probes, Spectrum Orange; Vysis Inc.) plus chromosome 18 centromeric probe (locus D18Z1, Spectrum Aqua; Vysis Inc.); (3) chromosome 13 (locus RB1, Spectrum Orange; Vysis Inc.) or chromosome 21 (loci D21S259, D21S341, D21S342, Spectrum Orange; Vysis Inc.) locus-specific probe plus chromosome 18 centromeric probe (locus D18Z1, Spectrum Aqua; Vysis Inc.). The centromeric probes for chromosomes 18, X, and Y were performed as “ploidy” control in triple or dual hybridization (the probe combinations are listed in Supplemental Table 1). Because the triple-colored probe mix included X and Y centromeric probes as “ploidy” controls for autosomes, the number of sex chromosomes was assessed by analyzing 1000 sperm cells on slides hybridized with the triple-colored probe mix.

After mixing, the probe solution was added to the slides with sperm from semen preparation, covered with a cover slip, sealed with rubber cement, and then co-denatured in a humidified chamber ThermoBrite (IRIS international, Inc, USA) at 78 °C for 5 min. After overnight hybridization at 37 °C, the coverslips were removed, and the slides were washed in 0.4 × SSC/0.3% Igepal at 72 °C for 2 min and then in 2 × SSC/0.1% Igepal at room temperature for 1 min. The slides were then air dried, treated with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstain, and analyzed using the automated CytoVision image analysis and capture system (Leica Biosystems Richmond, Inc., Richmond, IL, USA).

Scoring criteria

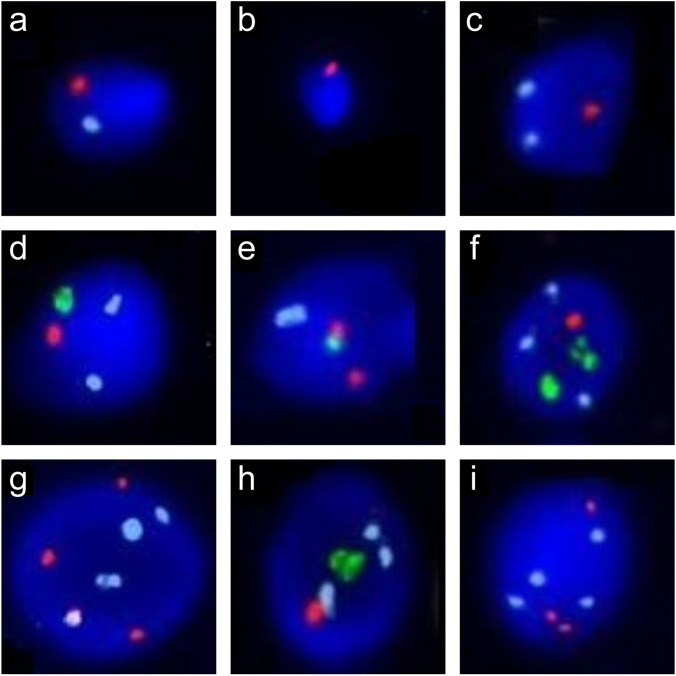

Nuclei were scored only when intact and clearly defined borders and strong fluorescent signals were present. In addition, two signals with the same color and equivalent fluorescent intensity separated by less than the diameter of one domain were scored as a single signal. A spermatozoon was scored as haploid for a given chromosome if it showed one signal for that chromosome and one signal for the other control chromosome (Fig. 1a). The numerical abnormalities were defined as follows: (1) nullisomy, if a given chromosome had no signal and the other control chromosome had one signal (Fig. 1b); (2) disomy, if a given chromosome had two signals and the other control chromosome had one signal (Fig. 1c); (3) diploidy, if both the given and the control chromosomes had two signals (Fig. 1d); (4) “others” consisting of trisomy, if a given chromosome had three signals and the other control chromosome had one signal (Fig. 1e); triploidy, if both the given and the control chromosomes had three signals (Fig. 1f); tetraploidy, if both the given and the control chromosomes had four signals (Fig. 1g); multiple aneuploidy, if the given chromosome and the control chromosome had discordance in signals different from those described (Fig. 1h–i).

Fig. 1.

Examples of signal patterns of chromosomal numerical abnormalities under fluorescence microscopy. The probes were labeled in different colors: orange, the Y chromosome; green, the X chromosome; and aqua, a given autosome. a–d and f–i A given autosome was evaluated using the sex chromosomes as the “ploidy” controls. e The sex chromosomes were evaluated using a given autosome as the “ploidy” control. a Haploidy. b Nullisomy. c Disomy. d Diploidy. e Trisomy. f Triploidy. g Tetraploidy. h–i Multiple aneuploidies

The scoring process was accomplished using the automated FISH system, GSL-120 (Leica Biosystems Richmond, Inc), and two experienced technicians. The GSL-120 is automated slide loading, cell finding, capturing system using scanning and image acquisition and analysis software tools. After capturing about 1000 sperm cells, the system automatically processes the signals and classifies the different signal patterns. After classification, the technicians double-checked the signal from each cell using the abovementioned scoring criterion, thereby guaranteeing the accuracy of classification.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance or nonparametric tests (when data were not normally distributed, and the error variance was unequal). A Student–Newman–Keuls or Steel–Dwass post-test was used for further comparison when there was statistical significance across groups. All tests were conducted using SPSS (v.22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and results with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Here, 248,811 spermatozoa were scored in ten donors, with a mean of 24,881 ± 381 spermatozoa per donor. Data pooling revealed 246,658 haploid spermatozoa, with 818 nullisomic, 393 disomic, 894 diploid, 13 triploid, 8 tetraploid, 3 trisomic, and 24 cells exhibited multiple aneuploidies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of numerical chromosome abnormalities in ten donors

| Donor no | Haploidy | Nullisomy | Disomy | Diploidy | Triploidy | Tetraploidy | Trisomy | Multiple aneuploidy | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25,192 (99.39%) | 67 (0.26%) | 41 (0.16%) | 43 (0.17%) | 2 (0.01%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.01%) | 25,347 |

| 2 | 24,584 (99.28%) | 67 (0.27%) | 35 (0.14%) | 71 (0.29%) | 3 (0.01%) | 1 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.00%) | 24,762 |

| 3 | 24,233 (98.80%) | 102 (0.42%) | 44 (0.18%) | 142 (0.58%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 5 (0.02%) | 24,527 |

| 4 | 24,104 (99.01%) | 78 (0.32%) | 47 (0.19%) | 112 (0.46%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (0.01%) | 24,345 |

| 5 | 24,833 (99.09%) | 157 (0.63%) | 34 (0.14%) | 37 (0.15%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 25,061 |

| 6 | 25,246 (98.89%) | 71 (0.28%) | 70 (0.27%) | 131 (0.51%) | 4 (0.02%) | 2 (0.01%) | 1 (0.00%) | 4 (0.02%) | 25,529 |

| 7 | 24,757 (99.06%) | 62 (0.25%) | 29 (0.12%) | 135 (0.54%) | 2 (0.01%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.00%) | 5 (0.02%) | 24,991 |

| 8 | 24,650 (99.13%) | 115 (0.46%) | 26 (0.10%) | 75 (0.30%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 24,867 |

| 9 | 24,895 (99.33%) | 34 (0.14%) | 41 (0.16%) | 84 (0.34%) | 2 (0.01%) | 2 (0.01%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (0.02%) | 25,062 |

| 10 | 24,164 (99.36%) | 65 (0.27%) | 26 (0.11%) | 64 (0.26%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 24,320 |

| Sum | 246,658 (99.13%) | 818 (0.33%) | 393 (0.16%) | 894 (0.36%) | 13 (0.01%) | 8 (0.00%) | 3 (0.00%) | 24 (0.01%) | 248,811 |

Aneuploidy rates per chromosome

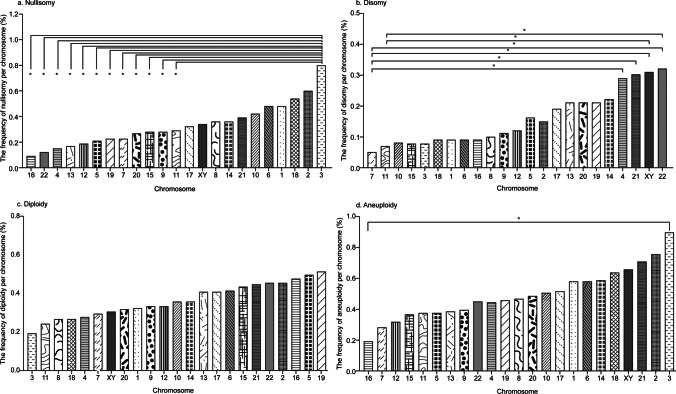

A total of 818 nullisomic and 393 disomic sperm cells were observed, accounting for 0.49% of the 248,811 sperm cells analyzed (Table 2). The mean nullisomy and disomy frequency per chromosome ranged from 0.09 to 0.80% and 0.05 to 0.32%, respectively, with a significant difference in the frequency among chromosomes (p < 0.001) (Table 3). For nullisomy, the frequency for chromosome 3 was significantly higher than chromosomes 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, and 22 (p < 0.05). However, it was not significantly different from chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 8, 10, 14, 17, 18, 21, and sex nullisomy (p > 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The upper bound of 95% confidence interval for the frequency of nullisomy per chromosome ranged from 0.18% (chromosome 16) to 1.34% (chromosome 3) (Table 6). For disomy, the rate for chromosomes 4, 21, 22, X, and Y was higher than other chromosomes, especially significantly higher than chromosome 7 (p < 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Moreover, disomy X, Y, and 22 were significantly higher than disomy 11 (p < 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The upper bound of 95% confidence interval for the frequency of disomy per chromosome ranged from 0.10% (chromosome 7) to 0.51% (chromosome sex) (Table 6). The frequency of aneuploidy per chromosome was calculated by summing the frequencies of nullisomy and disomy per chromosome, resulting in a range from 0.19% (chromosome 16) to 0.89% (chromosome 3) (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the incidence of aneuploidy between any different chromosomes (p > 0.05) except the difference between chromosome 3 and chromosome 16 being significant (p < 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The upper bound of 95% confidence interval for the frequency of aneuploidy per chromosome ranged from 0.27% (chromosome 16) to 1.46% (chromosome 3) (Table 6).

Table 3.

The frequency of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, aneuploidy, and chromosomal numerical abnormalities per chromosome

| Type of abnormality | Chromosome | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| Nullisomy* | 0.48a,b | 0.60a,b | 0.80b | 0.15a | 0.21a | 0.48a,b | 0.23a | 0.36a,b | 0.28a | 0.42a,b | 0.29a | 0.19a | 0.17a | 0.36a,b |

| Disomy* | 0.09a,b,c | 0.15a,b,c | 0.08a,b,c | 0.29b,c | 0.16a,b,c | 0.09a,b,c | 0.05a | 0.10a,b,c | 0.11a,b,c | 0.08a,b,c | 0.07a,b | 0.12a,b,c | 0.21a,b,c | 0.22a,b,c |

| Diploidy* | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.35 |

| Others* | 0.01a,b | 0.01a,b | 0.01a,b | 0.01a,b | 0.08b,c | 0.03a,b | 0.03a,b | 0.01a,b | 0.00a | 0.01a,b | 0.02a,b | 0.00a | 0.02a,b | 0.10c |

| Aneuploidy** | 0.57a,b | 0.75a,b | 0.89b | 0.44a,b | 0.37a,b | 0.57a,b | 0.28a,b | 0.46a,b | 0.39a,b | 0.50a,b | 0.37a,b | 0.31a,b | 0.38a,b | 0.58a,b |

| Total numerical abnormality*** | 0.90 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 1.03 |

| Type of abnormality | Chromosome | p-value | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | Sex total | Mean | SD | XX | XY | YY | ||

| Nullisomy* | 0.28a | 0.09a | 0.32a,b | 0.54a,b | 0.23a | 0.27a | 0.39a,b | 0.12a | 0.34a,b | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.000 | |||

| Disomy* | 0.08a,b,c | 0.09a,b,c | 0.19a,b,c | 0.09a,b,c | 0.21a,b,c | 0.21a,b,c | 0.30b,c | 0.32c | 0.31c | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.000 |

| Diploidy* | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.551 | |||

| Others* | 0.00a | 0.04a,b | 0.01a,b | 0.00a | 0.07a,b,c | 0.00a | 0.01a,b | 0.02a,b | 0.02a,b | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.000 | |||

| Aneuploidy** | 0.36a,b | 0.19a | 0.51a,b | 0.63a,b | 0.45a,b | 0.48a,b | 0.70a,b | 0.44a,b | 0.65a,b | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.015 | |||

| Total numerical abnormality*** | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 1.03 | 0.80 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.263 | |||

*The frequencies per chromosome were calculated as follows: nullisomy, dividing the number of nullisomic sperm cells by the total number of sperm cells counted in all donors for a particular chromosome; disomy, dividing the number of disomic sperm cells by the total number of sperm cells counted in all donors for a particular chromosome; diploidy and others, dividing the number of total diploid sperm cells or “others” cells by the total number of sperm cells counted in all donors for a particular chromosome

**The frequency of aneuploidy per chromosome was calculated by summing the frequencies of nullisomy and disomy per chromosome

***The frequency of total numerical abnormality per chromosome was calculated by summing the frequencies of aneuploidy, diploidy, and others per chromosome

(a–c) Different subgroups resulted from Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test comparing the frequency among chromosomes. Chromosomes with no significant difference in the frequency (p > 0.05) were classified into the same subgroup, and chromosomes with a significant difference in the frequency (p < 0.05) were classified into different subgroups

Fig. 2.

Frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and aneuploidy per chromosome. Bar plot of frequencies per chromosome in normozoospermic donors. a Nullisomy per chromosome. b Disomy per chromosome. c Diploidy per chromosome. d Aneuploidy per chromosome. *p < 0.05 (the Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test was used to calculate the test statistic for all pairwise comparisons of 23 chromosomes to determine whether the frequencies between each pair of chromosomes were significantly different)

Table 6.

The upper bound of 95% confidence interval for mean frequency of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, others, aneuploidy, and total numerical abnormality per chromosome

| Chromosome | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nullisomy | 0.82 | 0.86 | 1.34 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.97 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.53 |

| Disomy | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.51 |

| Diploidy | 0.48 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.45 |

| Others | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Aneuploidy* | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.46 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 1.08 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.94 |

| Total numerical abnormality** | 1.35 | 1.58 | 1.68 | 1.03 | 1.29 | 1.48 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 1.07 | 1.45 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 1.16 | 1.23 | 1.49 | 1.13 | 1.63 | 1.31 | 1.25 |

*The frequency of aneuploidy per chromosome was calculated by summing the frequencies of nullisomy and disomy per chromosome

**The frequency of total numerical abnormality per chromosome was calculated by summing the frequencies of aneuploidy, diploidy, and others per chromosome

Diploidy and other abnormalities per chromosome

The mean frequency of diploidy per chromosome ranged from 0.19 to 0.51% (Table 3), although no significant difference was observed in the frequency of diploidy among chromosomes (p = 0.551) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Since few sperm cells are polyploid (e.g., triploid or tetraploid), frequencies per chromosome could not be analyzed due to insufficient statistical power. However, these instances were reflected in the frequency of total numerical abnormalities per chromosome, which was determined by summing the frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and others. The mean frequency of total numerical abnormalities per chromosome ranged from 0.59% (chromosome 7) to 1.21% (chromosome 2) (Table 3); however, there was no significant difference in these frequencies between different chromosomes (p = 0.263) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The upper bounds of 95% confidence interval for the frequency of total numerical abnormality per chromosome ranged from 0.84% (chromosome 7) to 1.68% (chromosome 3) (Table 6).

Mean aneuploidy rate per donor

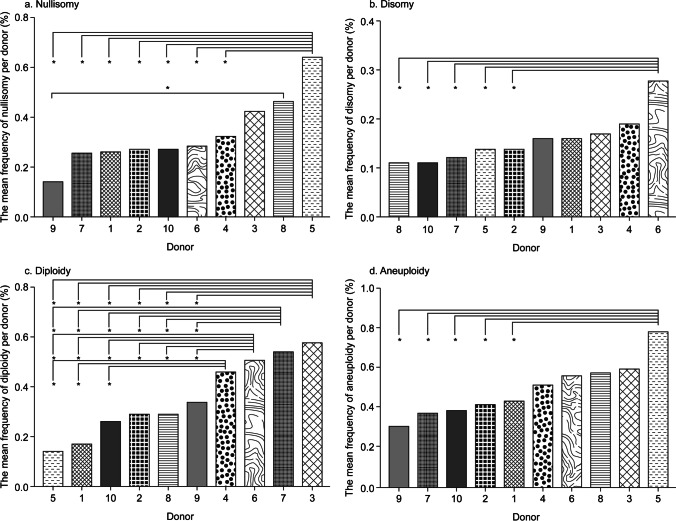

The mean frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and aneuploidy per donor were calculated by averaging the respective frequencies in autosomes 1 through 22 and the sex chromosomes for each donor. The mean nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and aneuploidy frequencies per donor were 0.33% ± 0.13%, 0.16% ± 0.05%, 0.36% ± 0.15%, and 0.49% ± 0.13%, respectively (Table 4). The mean nullisomy frequency of donor 9 was significantly lower than that of donors 8 and 5 (p < 0.05), and the mean nullisomy frequency of donor 5 was significantly higher than that of donors 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 10 (p < 0.05) (Table 4 and Fig. 3). The mean disomy frequency of donor 6 was significantly higher than that of donors 2, 5, 7, 8, and 10 (p < 0.05), and the mean diploidy frequencies of donors 1, 5, and 10 were significantly lower than that of donors 3, 4, 6, and 7 (p < 0.05) (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Furthermore, the mean diploidy frequency of donors 2, 8, and 9 was significantly lower than that of donors 3, 6, and 7 (p < 0.05), and the mean aneuploidy frequency of donor 5 was significantly higher than that of donors 1, 2, 7, 9, and 10 (p < 0.05) (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Overall, donor 5 had the highest mean frequency of nullisomy and aneuploidy and the lowest mean frequency of diploidy among donors, whereas donor 6 had the highest mean frequency of disomy (Table 4 and Fig. 3).

Table 4.

The mean frequency of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and aneuploidy per donor

| Type of abnormality | Donor no | p-value | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | mean | SD | ||

| Nullisomy* | 0.26a,b | 0.27a,b | 0.42a,b,c | 0.32a,b | 0.64c | 0.28a,b | 0.25a,b | 0.46b,c | 0.14a | 0.27a,b | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.000 |

| Disomy* | 0.16a,b | 0.14a | 0.17a,b | 0.19a,b | 0.14a | 0.28b | 0.12a | 0.11a | 0.16a,b | 0.11a | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.015 |

| Diploidy* | 0.17a | 0.29a,b | 0.58c | 0.46b,c | 0.14a | 0.51c | 0.54c | 0.29a,b | 0.34a,b | 0.26a | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.000 |

| Others* | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.167 |

| Aneuploidy** | 0.43a | 0.41a | 0.59a,b | 0.51a,b | 0.78b | 0.56a,b | 0.37a | 0.57a,b | 0.30a | 0.38a | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.001 |

| Total numerical abnormality*** | 0.61a | 0.73a,b | 1.19c | 1.00a,b,c | 0.92a,b,c | 1.11b,c | 0.94a,b,c | 0.87a,b,c | 0.67a | 0.65a | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.000 |

*The mean frequencies per donor were calculated as follows: nullisomy, dividing the total number of nullisomic sperm cells in 22 rounds of FISH tests by the total number of sperm cells counted for a particular donor; disomy, dividing the total number of disomic sperm cells in 22 rounds of FISH tests by the total number of sperm cells counted for a particular donor; diploidy and others, dividing the total number of diploid sperm cells or “others” sperm cells in 22 round FISH tests by the total number of sperm cells counted for a particular donor

**The mean frequency of aneuploidy per donor was calculated by summing the frequencies of nullisomy and disomy per donor

***The mean frequency of total numerical abnormality per donor was calculated by summing the frequencies of aneuploidy, diploidy, and others per donor

(a–c) Different subgroups resulted from Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test comparing the frequency among donors. Donors with no significant difference in the frequency (p > 0.05) were classified into the same subgroup, and donors with a significant difference in the frequency (p < 0.05) were classified into different subgroups

Fig. 3.

Mean frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, and aneuploidy per donor. Bar plot of the mean frequency per donor. a Nullisomy per donor. b Disomy per donor. c Diploidy per donor. d Aneuploidy per donor. *p < 0.05 (the Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test was used to calculate the test statistic for all pairwise comparisons of ten donors to determine whether the frequencies between each pair of donors were significantly different.)

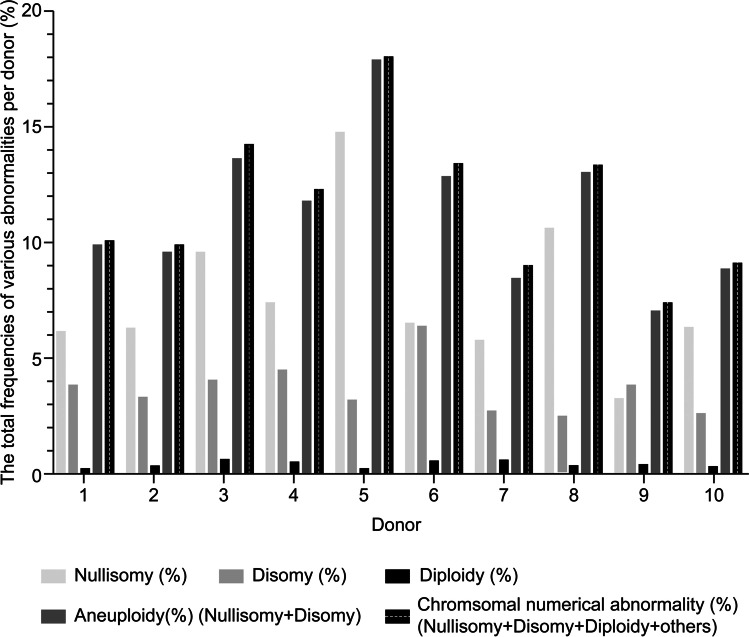

Total aneuploidy rate per donor

The total frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, and aneuploidy per donor were calculated by adding the frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, and aneuploidy for autosomes 1 through 22 and the sex chromosomes for each donor. The total frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, and aneuploidy were 7.62 ± 3.06%, 3.63 ± 1.12%, and 11.25 ± 3.05%, respectively (Table 5 and Fig. 4). The incidence of diploidy and “others” was calculated by dividing the number of diploid or “others” sperm cells by the total number of sperm cells counted for each donor with an average frequency of 0.36 ± 0.15% and 0.02 ± 0.01% per donor, respectively (Table 5 and Fig. 4). The total numerical abnormality per donor was calculated according to the sum of diploidy, aneuploidy, and “other” frequencies, resulting in an average frequency of total numerical abnormality per donor of 11.63 ± 3.03% (Table 5 and Fig. 4).

Table 5.

The total frequencies of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, others, aneuploidy, and chromosomal numerical abnormality per donor

| Donor no | Nullisomy* (%) | Disomy* (%) | Diploidy* (%) | Others* (%) | Aneuploidy** (%) | Total numerical abnormality*** (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.08 | 3.82 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 9.90 | 10.09 |

| 2 | 6.27 | 3.18 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 9.45 | 9.77 |

| 3 | 9.58 | 4.01 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 13.59 | 14.19 |

| 4 | 7.32 | 4.45 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 11.77 | 12.25 |

| 5 | 14.73 | 3.14 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 17.87 | 18.02 |

| 6 | 6.45 | 6.37 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 12.82 | 13.37 |

| 7 | 5.71 | 2.70 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 8.41 | 8.98 |

| 8 | 10.57 | 2.41 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 12.98 | 13.29 |

| 9 | 3.18 | 3.76 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 6.94 | 7.31 |

| 10 | 6.29 | 2.50 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 8.79 | 9.06 |

| Mean | 7.62 | 3.63 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 11.25 | 11.63 |

| SD | 3.06 | 1.12 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 3.05 | 3.03 |

*The total frequencies per donor were calculated as follows: nullisomy, summing the frequencies of nullisomy from autosomes 1–22 and 2 sex chromosomes for a particular donor; disomy, summing the frequencies of disomy from autosomes 1–22 and 2 sex chromosomes for a particular donor; diploidy and others, dividing the total number of diploid or “others” sperm cells from 22 rounds of FISH tests by the total number of sperm cells counted for a particular donor

**The total frequency of aneuploidy per donor was calculated by summing the frequencies of nullisomy and disomy per donor

***The total frequency of numerical abnormality per donor was calculated by summing the frequencies of aneuploidy, diploidy, and others per donor

Fig. 4.

The total frequency of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, aneuploidy, and numerical abnormalities per donor. Bar plot of total frequency of nullisomy, disomy, diploidy, aneuploidy, and numerical abnormalities per normozoospermic donor (%)

Discussion

Although many FISH studies have reported on sperm aneuploidy frequency, not all chromosomes and abnormal types have been investigated in the normal population in a single study. Results obtained using the strategy for assessing 23 chromosomes and all types of abnormalities can provide valuable information regarding aneuploidy. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to obtain aneuploidy frequency of every chromosome with the most abnormalities, thereby revealing the aneuploidy frequency that most closely approaching to the true value behind the ten normozoospermic males.

The dominant chromosomal numerical abnormalities in normozoospermic men were disomy, nullisomy, and diploidy. Among the published data, disomy was the most extensively studied abnormality, particularly for chromosomes 13, 18, 21, and XY because of the relative high incidence of trisomy in live births for these five chromosomes. When compiling control donor data from 49 sperm FISH studies (Supplemental Table 5), the mean disomy frequencies for 13, 18, 21, and the sex chromosomes were 0.15%, 0.14%, 0.22%, and 0.41% (XX-0.11%; XY-0.20%; YY-0.12%), respectively, which was similar to the results obtained in this study 0.21%, 0.09%, 0.30%, and 0.31% (XX-0.06%; XY-0.21%; YY-0.04%) (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 5). Moreover, the mean frequencies of disomy for the other 19 chromosomes ranged from 0.08 to 0.25% in complied data, which were similar to that of the present study with a range of 0.05 to 0.32% (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 5).

The diploidy frequency has also been extensively studied, with a mean frequency of 0.22 ± 0.14% for each hybridization probe set (Supplemental Table 5) in the compiled data, similar to 0.36±0.09% in the present study (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 5).

Although not as widely studied as that of disomy and diploidy, the frequency of nullisomy has also been reported in the normal population [19–34]. Upon reviewing 16 sperm FISH studies reporting nullisomy (Supplemental Table 6), the mean frequencies of nullisomy for chromosomes 13, 18, 21, and sex chromosomes were 0.51%, 0.18%, 0.31%, and 0.43% (Supplemental Table 6). Compared with the results of 0.17%, 0.54%, 0.39%, and 0.34% in this study, the incidence of nullisomy for chromosome 21 and the sex chromosomes was similar to, whereas, the incidence of nullisomy 13 was slightly higher, and the incidence of nullisomy 18 was slightly lower than that of the present study (Table 4 and Supplement Table 6). Nullisomy for the other 19 chromosomes was relatively less reported. Among the 16 studies, an average of 2 studies reported the nullisomy frequencies for other 15 chromosomes 1–2, 4, 6–12, 15–17, 19, and 22 (range: 0.02–1.32%), while no studies reported nullisomy frequencies for the other 4 chromosomes 3, 5, 14, and 20 (Supplemental Table 6). The mean frequencies of nullisomy for chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 15, 17, and 19 in compiled data were close to or within two- to three-fold the present study (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 6). Nevertheless, the mean frequencies of nullisomy for chromosomes 8, 10, and 12 (0.02%, 0.05%, and 0.06%) in the compiled data were much lower than 0.36%, 0.42%, and 0.19% in the present study. And the mean frequencies of nullisomy for chromosomes 16 and 22 (0.73% and 1.32%) in the compiled data were much higher than 0.09% and 0.12% in the present study (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 6). Moreover, the average incidence of nullisomy per chromosome was twice as high as that of disomy (Table 3). Bell et al. simultaneously studied the genomes of thousands of individual sperm using Sperm-seq, in which the authors observed 2.4-fold more chromosome losses than gains (554 losses vs. 233 gains) [35].

Based on the disomy and nullisomy frequencies per chromosome (Table 3), the frequency of aneuploidy (nullisomy + disomy) per chromosome was obtained in the present study (Table 3). The mean frequencies of aneuploidy for chromosomes 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 21, and XY in four normal control donors reported by M.G. Pang et al. [29] ranged from 0.20 to 0.43%, which was similar to 0.28–0.70% in this study (Table 3). In addition, Tang et al. [32] reported similar aneuploidy frequencies for chromosomes 13, 21, and sex chromosome to this study (0.52%, 0.50%, and 0.86% vs. 0.38%, 0.70%, and 0.65%, respectively), whereas, aneuploidy 18 reported by them (0.13%) was much lower than 0.63% in the present study (Table 3).

The total disomy, nullisomy, and aneuploidy (nullisomy + disomy) for each donor were obtained in this study based on the disomy and nullisomy frequencies for all chromosomes and donors (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Neusser et al. [36] reported disomy frequencies of 23 chromosomes for three normal controls and their total disomy frequencies summing up 23 chromosomes were 2.10%, 3.94%, and 3.36%, which was similar to 3.63 ± 1.12% of the present study (Table 5).

The total aneuploidy was proposed to be estimated by formulae either the sum of disomy and nullisomy frequency, twice the disomy frequency, or twice the nullisomy frequency [29]. However, in case that the disomy and nullisomy frequencies differ much, the results calculated by these formulae would not be similar and the total aneuploidy could not be estimated reliably. Templado et al. [17] obtained a total disomy rate of 2.26% for the normal population by summing the disomy frequencies of 18 chromosomes (1–4, 6–9, 12–13, 15–6, 18, 20–22, and sex chromosome) compiled in 30 studies, which was similar to that of 2.69% in the present study for the same 18 chromosomes. In the absence of nullisomy frequencies for the corresponding chromosomes, Templado et al. [17] estimated the total aneuploidy as 4.5% by doubling the total disomy frequency (2 × 2.26% of disomy frequency). By doubling the disomy frequencies of the same 18 chromosomes, we obtained the total aneuploidy as 5.38% similar to Templado’s estimate. Alternatively, by summing disomy and nullisomy frequencies of the same 18 chromosomes, we obtained the total aneuploidy as 8.46%, which was nearly twice the Templado’s estimate. Thus, the total aneuploidy frequency may be most appropriately estimated by the sum of disomy and nullisomy frequency, as the incidence of aneuploidy tends to variate not only between chromosomes but also between different types of abnormality.

Moreover, the mean frequency of total numerical abnormality (nullisomy + disomy + diploidy + others) per donor was 11.63 ± 3.03% (range: 7.31 to 18.02%) in the present study (Table 5). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first FISH study reporting the frequency of total numerical abnormality referring to 23 chromosomes and most abnormalities. Our results added to a limited body of evidence, although more data are needed to validate the frequency and range of variation for the total numerical abnormality reported in the present study.

Many studies have investigated the frequency of numerical abnormalities in the sperm of infertile males. Those with poor semen parameters, including reduced sperm count, motility, and morphology reportedly have an increased rate of chromosome abnormalities in their gametes [37–39]. Moreover, the male partners in couples with recurrent miscarriages of unknown etiology [40] or repeated implantation failure after ICSI and IVF [41, 42], as well as the fathers of patients with Turner syndrome or Down syndrome [43, 44] also have an elevated rate of aneuploidy in their spermatozoa. Therefore, it is helpful for clinical consultation and diagnosis to screen at-risk population with high incidence of aneuploidy.

Observing whether an individual’s aneuploidy rate exceeds a confidence interval threshold for a normal fertile group is considered to be a method of screening individuals at risk of aneuploidy [19]. Specifically, according to the statement of the 95% confidence interval, any aneuploidy rate above the upper band will have a 95% probability of being significantly different from the normal fertile group, which might be indicated as “at-risk” for producing more aneuploid spermatozoa. García-Mengual et al. [19] reported that the upper bound of 95% confidence interval for disomy 1 was 0.11%, 2 (0.14%), 9 (0.09%), 13 (0.21%), 15 (0.68%), 16 (0.57%), 17 (0.24%), 18 (0.26%), 19 (0.62%), 21 (0.22%), 22 (0.35%), and XY (0.40%). Most of their upper bounds were close to that of the present study (Table 6), except that the upper bounds of disomy 15 and 16 exceeded that of the present study (0.14% and 0.13%) (Table 6). The upper bounds of nullisomy reported by García-Mengual et al. ranged from 0.25 to 1.91%. Their nullisomy bounds were generally higher than that of the present study, especially for nullisomy 16 (1.91%) and 22 (1.67%) being ten and eight times that of the present study (0.18% and 0.21%) (Table 6). It is worth noting that FISH results could vary between different studies due to different conditions such as the FISH protocols, probe strategies, microscopes, technicians, number of cells and donors analyzed, and probe type selected for assessing each chromosome. Thus, a reliable screening of high-risk groups is based on the comparison of one person’s aneuploidy rates to the upper bounds, in which the person’s aneuploidy rates must be obtained by using the same methods described in studies reporting the corresponding upper bounds.

In summary, we successfully evaluated the sperm aneuploidy for 23 chromosomes in ten normozoospermic males. One limitation of this study is the small number of donors. Although approximately 22,000 sperm cells from each donor were assessed, the total number of donors was small. Therefore, the identification of inter-individual variation requires analysis on a larger number of normozoospermic donors to obtain robust statistical power. Nonetheless, our data could assist in comprehensive understanding the chromosome aneuploidy frequency in normozoospermic males.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We express deepest gratitude to all the families enrolled in this study.

Author contribution

CL and FJ designed this study and revised the manuscript; YZ collected the donor sperm samples; SJZ and YZ performed the experiments; SJZ wrote the manuscript; FZ directed problem solving during the experiments and revised the manuscript; JW performed the statistical analysis; CL revised the manuscript and directed the critical discussion of the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2017SHZDZX01).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to patient confidentiality and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai JiAi Genetics & IVF Institute (JIAI E2018-23) and Human Sperm Bank of Fudan University (HSBOFU2021-01).

Consent to participate

All participants underwent genetic counseling and provided informed consent regarding donation and the purpose of the sperm aneuploidy study program.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saijuan Zhu, Email: Cintennis2007@aliyun.com.

Yong Zhu, Email: Zhuyong7563@fckyy.org.cn.

Feng Zhang, Email: zhangfeng@fudan.edu.cn.

Jiangnan Wu, Email: wjnhmm@126.com.

Caixia Lei, Email: Caixialei@hotmail.com.

Feng Jiang, Email: Jfsy001@163.com.

References

- 1.Ioannou D, Tempest HG. Meiotic nondisjunction: insights into the origin and significance of aneuploidy in human spermatozoa. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;868:1–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18881-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassold T, Hunt P. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:280–291. doi: 10.1038/35066065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu C, Li K. Chromosomal aneuploidy associated with clinical characteristics of pregnancy loss. Front Genet. 2021;12. 10.3389/fgene.2021.667697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gimovsky AC, Pham A, Moreno SC, Nicholas S, Roman A, Weiner S. Genetic abnormalities seen on CVS in early pregnancy failure. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:2142–2147. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1542677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler A, Morales C, Mademont-Soler I, Margarit E, Borrell A, Borobio V, et al. Overview of chromosome abnormalities in first trimester miscarriages: a series of 1,011 consecutive chorionic villi sample karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2017;152:81–89. doi: 10.1159/000477707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutaff-Lee C, Cordeiro L, Tartaglia N. Cognitive and medical features of chromosomal aneuploidy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;111:273–279. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb NE, Sherman SL, Hassold TJ. Effect of meiotic recombination on the production of aneuploid gametes in humans. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:250–255. doi: 10.1159/000086896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abruzzo MA, Hassold TJ. Etiology of nondisjunction in humans. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1995;25(Suppl 26):38–47. doi: 10.1002/em.2850250608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioannou D, Fortun J, Tempest HG. Meiotic nondisjunction and sperm aneuploidy in humans. Reproduction. 2019;157:R15–31. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandriff B, Gordon L, Ashworth L, Watchmaker G, Moore D, Wyrobek AJ, et al. Chromosomes of human sperm: variability among normal individuals. Hum Genet. 1985;70:18–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00389451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin RH. Chromosomal abnormalities in human sperm. Basic Life Sci. 1985;36:91–102. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2127-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudak E, Jacobs PA, Yanagimachi R. Direct analysis of the chromosome constitution of human spermatozoa. Nature. 1978;274:911–913. doi: 10.1038/274911a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egozcue J, Blanco J, Vidal F. Chromosome studies in human sperm nuclei using fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:441–452. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin RH, Ko E, Chan K. Detection of aneuploidy in human interphase spermatozoa by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1993;64:23–26. doi: 10.1159/000133552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu H, Miharu N, Mizunoe T, Nakaoka Y, Okamoto E, Ohama K. Detection of aneuploidy in human spermatozoa using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Jpn J Hum Genet. 1996;41:381–389. doi: 10.1007/BF01876328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downie SE, Flaherty SP, Matthews CD. Detection of chromosomes and estimation of aneuploidy in human spermatozoa using fluorescence in-situ hybridization. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:585–598. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.7.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Templado C, Vidal F, Estop A. Aneuploidy in human spermatozoa. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;133:91–99. doi: 10.1159/000323795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehdi M, Gmidène A, Brahem S, Guerin JF, Elghezal H, Saad A. Aneuploidy rate in spermatozoa of selected men with severe teratozoospermia. Andrologia. 2012;44(Suppl 1):139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2010.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Mengual E, Triviño JC, Sáez-Cuevas A, Bataller J, Ruíz-Jorro M, Vendrell X. Male infertility: establishing sperm aneuploidy thresholds in the laboratory. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:371–381. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acar H, Kilinç M, Cora T, Aktan M, Taşkapu H. Incidence of chromosome 8,10, X and Y aneuploidies in sperm nucleus of infertile men detected by FISH. Urol Int. 2000;64:202–208. doi: 10.1159/000030531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumgartner A, Van Hummelen P, Lowe XR, Adler ID, Wyrobek AJ. Numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities detected in human sperm with a combination of multicolor FISH assays. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1999;33:49–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(1999)33:1<49::aid-em6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burrello N, Calogero AE, De Palma A, Grazioso C, Torrisi C, Barone N, et al. Chromosome analysis of epididymal and testicular spermatozoa in patients with azoospermia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:362–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calogero AE, De Palma A, Grazioso C, Barone N, Romeo R, Rappazzo G, et al. Aneuploidy rate in spermatozoa of selected men with abnormal semen parameters. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1172–1179. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fakhrabadi MP, Kalantar SM, Montazeri F. Ashkezari MD, Fakhrabadi MP, Yazd SSN. FISH-based sperm aneuploidy screening in male partner of women with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2020;25. 10.1186/s43043-020-00031-6.

- 25.Lähdetie J, Saari N, Ajosenpää-Saari M, Mykkänen J. Incidence of aneuploid spermatozoa among infertile men studied by multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Med Genet. 1997;71:115–121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970711)71:1<115::AID-AJMG21>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martínez-Pasarell O, Nogués C, Bosch M, Egozcue J, Templado C. Analysis of sex chromosome aneuploidy in sperm from fathers of Turner syndrome patients. Hum Genet. 1999;104:345–349. doi: 10.1007/s004390050964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mateizel I, Verheyen G, Van Assche E, Tournaye H, Liebaers I, Van Steirteghem A. FISH analysis of chromosome X, Y and 18 abnormalities in testicular sperm from azoospermic patients. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2249–2257. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.9.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naccarati A, Zanello A, Landi S, Consigli R, Migliore L. Sperm-FISH analysis and human monitoring: a study on workers occupationally exposed to styrene. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2003;537:131–140. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pang MG, Hoegerman SF, Cuticchia AJ, Moon SY, Doncel GF, Acosta AA, et al. Detection of aneuploidy for chromosomes 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 21, X and Y by fluorescence in-situ hybridization in spermatozoa from nine patients with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1266–73. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfeffer J, Pang MG, Hoegerman SF, Osgood CJ, Stacey MW, Mayer J, et al. Aneuploidy frequencies in semen fractions from ten oligoasthenoteratozoospermic patients donating sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:472–478. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spriggs EL, Rademaker AW, Martin RH. Aneuploidy in human sperm: the use of multicolor FISH to test various theories of nondisjunction. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:356–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang SS, Gao H, Zhao Y, Ma S. Aneuploidy and DNA fragmentation in morphologically abnormal sperm. Int J Androl. 2010;33:e163–e179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tempest HG, Ko E, Rademaker A, Chan P, Robaire B, Martin RH. Intra-individual and inter-individual variations in sperm aneuploidy frequencies in normal men. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vegetti W, Van Assche E, Frias A, Verheyen G, Bianchi MM, Bonduelle M, et al. Correlation between semen parameters and sperm aneuploidy rates investigated by fluorescence in-situ hybridization in infertile men. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:351–365. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell AD, Mello CJ, Nemesh J, Brumbaugh SA, Wysoker A, McCarroll SA. Insights into variation in meiosis from 31,228 human sperm genomes. Nature. 2020;583:259–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2347-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neusser M, Rogenhofer N, Dürl S, Ochsenkühn R, Trottmann M, Jurinovic V, et al. Increased chromosome 16 disomy rates in human spermatozoa and recurrent spontaneous abortions. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1130–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finkelstein S, Mukamel E, Yavetz H, Paz G, Avivi L. Increased rate of nondisjunction in sex cells derived from low-quality semen. Hum Genet. 1998;102:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s004390050665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Härkönen K, Suominen J, Lähdetie J. Aneuploidy in spermatozoa of infertile men with teratozoospermia. Int J Androl. 2001;24:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2001.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hristova R, Ko E, Greene C, Rademaker A, Chernos J, Martin R. Chromosome abnormalities in sperm from infertile men with asthenoteratozoospermia. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1781–1783. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.6.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moosani N, Pattinson HA, Carter MD, Cox DM, Rademaker AW, Martin RH. Chromosomal analysis of sperm from men with idiopathic infertility using sperm karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:811–817. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57859-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubio C, Gil-Salom M, Simón C, Vidal F, Rodrigo L, Mínguez Y, et al. Incidence of sperm chromosomal abnormalities in a risk population: relationship with sperm quality and ICSI outcome. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2084–2092. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colombero LT, Hariprashad JJ, Tsai MC, Rosenwaks Z, Palermo GD. Incidence of sperm aneuploidy in relation to semen characteristics and assisted reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanco J, Gabau E, Gómez D, Baena N, Guitart M, Egozcue J, et al. Chromosome 21 disomy in the spermatozoa of the fathers of children with trisomy 21, in a population with a high prevalence of Down syndrome: increased incidence in cases of paternal origin. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1067–1072. doi: 10.1086/302058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soares SR, Templado C, Blanco J, Egozcue J, Vidal F. Numerical chromosome abnormalities in the spermatozoa of the fathers of children with trisomy 21 of paternal origin: generalised tendency to meiotic non-disjunction. Hum Genet. 2001;108:134–139. doi: 10.1007/s004390000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to patient confidentiality and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.