Abstract

A universal set of genes encodes the components of the dissociated, type II, fatty acid synthase system that is responsible for producing the multitude of fatty acid structures found in bacterial membranes. We examined the biochemical basis for the production of branched-chain fatty acids by gram-positive bacteria. Two genes that were predicted to encode homologs of the β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III of Escherichia coli (eFabH) were identified in the Bacillus subtilis genome. Their protein products were expressed, purified, and biochemically characterized. Both B. subtilis FabH homologs, bFabH1 and bFabH2, carried out the initial condensation reaction of fatty acid biosynthesis with acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) as a primer, although they possessed lower specific activities than eFabH. bFabH1 and bFabH2 also utilized iso- and anteiso-branched-chain acyl-CoA primers as substrates. eFabH was not able to accept these CoA thioesters. Reconstitution of a complete round of fatty acid synthesis in vitro with purified E. coli proteins showed that eFabH was the only E. coli enzyme incapable of using branched-chain substrates. Expression of either bFabH1 or bFabH2 in E. coli resulted in the appearance of a branched-chain 17-carbon fatty acid. Thus, the substrate specificity of FabH is an important determinant of branched-chain fatty acid production.

Bacteria synthesize fatty acids by using the type II, or dissociated, fatty acid synthase system. This biosynthetic pathway has been studied primarily in Escherichia coli, providing a fairly complete picture of the mechanisms that govern the synthesis of straight-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids (for reviews, see references 7, 24, and 25). The pathway consists of a collection of individual proteins encoded by unique genes that function in concert to produce the variety of fatty acid products found in bacteria. The genomes of a number of bacteria are now known, and all these organisms possess a highly related, and clearly identified, set of genes that carry out the reactions in the pathway. E. coli and many other gram-negative bacteria synthesize even-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Fatty acid synthesis is initiated by the condensation of acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) with malonyl-acyl carrier protein (malonyl-ACP) by β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III, the product of the fabH gene (14, 15, 31). However, other bacteria produce such a great variety of fatty acid structures that E. coli cannot be considered typical (25).

Many gram-positive organisms, such as the bacilli, staphylococci, and streptomycetes, produce odd- and even-carbon-number branched-chain fatty acids (20). These branched-chain fatty acid structures have either iso- or anteiso-methyl branches, and it is tenable to hypothesize that the FabH component in organisms like B. subtilis would be able to accept isovaleryl-CoA, isobutyryl-CoA, and 2-methylbutyryl-CoA as primers to produce these fatty acids. Thus, earlier work by Butterwork and Bloch (5), showing that acyl-CoA:ACP transacylase activity, one of the reactions catalyzed by FabH (31), in Bacillus cell extracts was selective for branched-chain acyl-CoAs is consistent with the idea that bFabH prefers these primers. Genetic experiments with B. subtilis demonstrate that these CoA thioesters are essential intermediates in fatty acid synthesis and arise from iso- and anteiso-branched α-keto acids derived from the biosynthetic pathways for the amino acids valine, leucine, and isoleucine (33, 34). The enzyme responsible for the formation of these acyl-CoAs is a specialized branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, and mutations in the activity of this enzyme system result in strains that are auxotrophic for branched-chain acids (34). The Streptomyces glaucescens FabH enzyme efficiently utilizes both butyryl-CoA and isobutyryl-CoA and is thought to be responsible for initiating branched-chain fatty acid synthesis in this organism (10). eFabH is selective for acetyl-CoA (12, 14, 15, 31), and its low activity with butyryl-CoA (12) suggests that bulkier branched-chain CoA thioesters may not be substrates, although this idea has not been experimentally tested. In addition to the FabH component, it is also possible that all of the enzymes of the elongation cycle in gram-negative organisms (FabF, FabG, FabZ, and FabI) cannot utilize branched-chain intermediates. The goal of this study was to biochemically characterize the FabH enzymes of B. subtilis and determine if the FabH component is unique among the enzymes of type II fatty acid synthases in its selectivity toward branched-chain intermediates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Sources of supplies were as follows: Amersham-Pharmacia Biotechnology ([2-14C]malonyl-CoA; specific activity, 56.0 Ci/mol); DuPont-New England Nuclear ([1-14C]acetyl-CoA; specific activity, 45.8 Ci/mol); Sigma (fatty acids, ACP, and acyl-CoAs); and Matreya, Inc. (fatty acid methyl esters). Proteins were quantitated by the Bradford method by using gamma globulin as a standard (4). The E. coli FabH, FabG, FabA, FabZ, FabI, and FabD proteins were purified as described previously (11–13). All other chemicals were of reagent grade or better.

Construction of expression vectors and purification of the His-tag proteins.

The fabH1 and fabH2 genes were amplified from genomic DNA isolated from B. subtilis. Primers created novel restriction sites for XhoI or NdeI at the amino terminus of the predicted coding sequence and BamHI immediately downstream of the stop codon. The fabH1 PCR primer pair consisted of 5′-CTCGAGAAAGCTGGAATACTTGGTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCTCTTGTGTGCACCTCACCT-3′, and the fabH2 primer pair consisted of 5′-GTGAGGTGCACACCATATGACTAAA-3′ and 5′-GGATCCGGAAGAAACATCAGAAGAACAG-3′. The PCR products were ligated into plasmid pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and transformed into E. coli INVαF′. Plasmids were isolated and digested with either XhoI and BamHI for fabH1 or NdeI and BamHI for fabH2. The fragments were isolated and ligated into plasmid pET-15b digested with XhoI and BamHI or with NdeI and BamHI. These ligation mixtures were used to transform strain BL21(DE3). One clone was chosen for each gene, and the insert DNA was sequenced to verify the absence of any PCR artifacts. The proteins were purified as described previously (12).

Enzyme assays.

A filter disc assay was used to assay the activity of the FabH proteins with acetyl-CoA as the substrate essentially as described by Tsay et al. (31). The assays contained 25 μM ACP, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 65 μM malonyl-CoA, 45 μM [1-14C]acetyl-CoA (specific activity, 45.8 Ci/mol), E. coli FabD (0.2 μg), and 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in a final volume of 40 μl. The reaction was initiated by the addition of FabH, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 12 min. A 35-μl aliquot was then removed and deposited on a Whatman 3MM filter disc. The discs were washed with three changes (20 ml/disc for 20 min each) of ice-cold trichloroacetic acid. The concentration of the trichloroacetic acid was reduced from 10 to 5 to 1% in each successive wash. The filters were dried and counted in 3 ml of scintillation cocktail.

The second FabH assay used gel electrophoresis to separate and quantitate the products (12). This assay mixture contained 25 μM ACP, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 70 μM [2-14C]malonyl-CoA (specific activity, 9.4 Ci/mol), 45 μM substrate (acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, butyryl-CoA, isobutyryl-CoA, valeryl-CoA, isovaleryl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, heptanoyl-CoA, octanoyl-CoA, or 2-methylbutyryl-CoA), FabD (0.2 μg), 100 μM NADPH, FabG (0.2 μg), and 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in a final volume of 40 μl. The reaction was initiated by the addition of FabH, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 12 min and then placed in an ice slurry, gel loading buffer was added, and the mixture was loaded onto a conformationally sensitive 13% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.5 to 2.0 M urea depending on the chain length of the acyl-ACP product (10–12). Electrophoresis was performed at 25°C and 32 mA/gel. The gels were dried, and the bands were quantitated by exposure of the gel to a PhosphoImager screen. Specific activities were calculated from the slopes of the plot of product formation versus FabH protein concentration in the assay.

Synthesis of 2-methylbutyryl-CoA.

2-Methylbutyryl-CoA was synthesized from the mixed acid anhydride of 2-methylbutyric acid by a modified method of the thiol ester synthesis described by Stadtman (27). To prepare the mixed acid anhydride, 10 mmol of 2-methylbutyric acid and 10 mmol of pyridine were dissolved in anhydrous ethyl ether (at 0°C), and 10 mmol of ethylchloroformate was added dropwise with stirring. The mixture was left at 0°C for 1 h, and the insoluble pyridine hydrochloride was then removed by centrifugation. The yield of mixed acid anhydride was determined by using the hydroxylamine-ferric chloride method (26). To form acyl-CoA derivatives, 75 μmol of the mixed acid anhydride was added dropwise with shaking to a cold aqueous solution containing 18.7 μmol of CoA-SH in 0.2 M KHCO3 (adjusted to pH 7.5). The pH was then adjusted to 6.0 with 1 M HCl, and then the aqueous layer was extracted three times with an equal volume of ethyl ether. The last traces of ether were removed from the aqueous solution by bubbling with nitrogen, and the final product, 2-methylbutyryl-CoA, was quantitated with the hydroxylamine-ferric chloride method (26).

Reconstitution of fatty acid synthesis in vitro.

A single cycle of fatty acid elongation was reconstituted in vitro by sequentially adding the individual enzymes that catalyzed each reaction in the cycle as described by Heath and Rock (11). The reaction mixtures included, in a volume of 40 μl, 50 μM ACP, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 M Na2PO4 (pH 7.4), 100 μM NADPH, 100 μM NADH, 65 μM acetyl-CoA or isovaleryl-CoA, and 30 μM [2-14C]malonyl-CoA (specific activity, 56.0 Ci/mol), and the individual proteins were added at concentrations of 0.2 μg/reaction mixture. The assay mixtures were incubated for 20 min at 37°C and analyzed by conformationally sensitive gel electrophoresis in 13% polyacrylamide gels containing 0.5 M urea for acetyl-CoA and 1.0 M urea for isovaleryl-CoA. Product formation was quantitated with a PhosphoImager.

Fatty acid analysis.

Plasmids were constructed to express bFabH1 and bFabH2 in E. coli by digesting the expression vectors with XbaI and BamHI and placing the inserts into pBluescript. Colonies of E. coli SJ53 harboring either the pKHC1 (bFabH1), pKHC2 (bFabH2), or pBluescript (control) plasmid were grown on M9 minimal agar medium (22) supplemented with 0.1% Casamino Acids, 0.4% glycerol, 0.01% methionine, 0.0005% thiamine, 100 μM β-alanine, and 50 μg of ampicillin per ml, harvested from the plates, and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were extracted as described by Bligh and Dyer (3), and fatty acid methyl esters were prepared by using HCl-methanol. The fatty acid methyl esters were fractionated with a Hewlett-Packard model 5890 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector. Separations were performed with a glass column (2 m by 4 mm, internal diameter) containing Supelcoport (100/120 mesh) coated with 3% SP2100 at 190°C. The injector temperature was 270°C, the detector temperature was 190°C, and the flow rate of the carrier gas (nitrogen) was 40 ml/min. Fatty acid methyl esters were identified by comparing their retention times with branched-chain and straight-chain fatty acid methyl ester standards (Matreya). The fatty acid compositions were expressed as weight percent.

RESULTS

Identification of putative FabH homologs in B. subtilis.

The E. coli FabH sequence (31) was used to search the B. subtilis genome (21) for related sequences. This analysis identified two open reading frames that encoded putative FabH sequences that we named bFabH1 and bFabH2 (Fig. 1). bFabH1 corresponded to open reading frame yjaX. This open reading frame consisted of 971 bp predicted to encode a protein that was 45% identical and 56% similar to E. coli FabH. The second FabH homolog, bFabH2, corresponded to the 973-bp open reading frame yhfB. bFabH2 was 38% identical and 48% similar to the E. coli FabH enzyme. bFabH1 was 46% identical and 54% similar to bFabH2. These data showed that there were two putative FabH condensing enzymes in Bacillus.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of E. coli FabH with B. subtilis FabH1 and FabH2. Identical amino acids shared by any two of the FabH proteins are shaded in black. The active site Cys is denoted by an asterisk, and the putative acetyl-CoA binding site between residues 156 and 167 is denoted by gray shading (31).

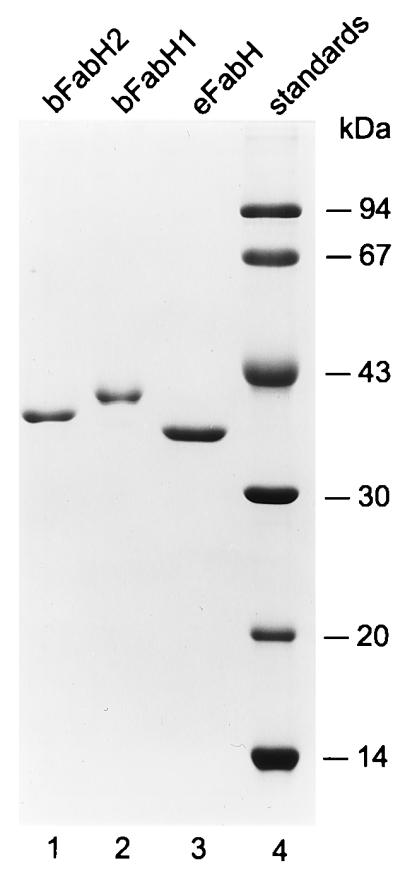

The two open reading frames for the predicted bFabH proteins were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pET15-b vector, and the His-tagged versions of the proteins were expressed and purified (Fig. 2). The tagged bFabH1 protein exhibited a molecular size of 42.7 kDa, and the bFabH2 protein had an apparent size of 39.8 kDa, as compared to the 37.6-kDa eFabH.

FIG. 2.

Expression and purification of FabH proteins. The FabH proteins were expressed as His-tag fusion proteins and purified by Ni2+-chelate affinity chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were analyzed by using sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis through a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and the proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue.

Substrate specificity of B. subtilis FabHs.

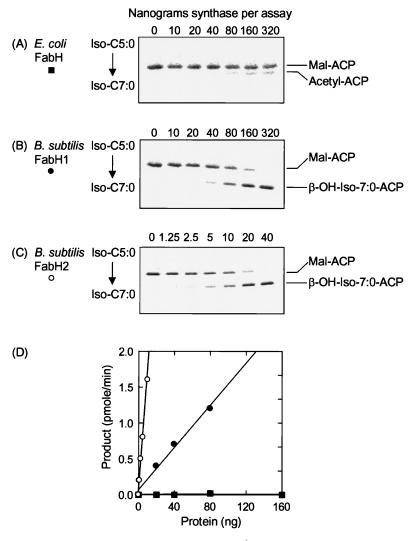

Two assays were used to determine the specific activity of B. subtilis and E. coli FabH enzymes with acetyl-CoA. The filter disc assay, using [14C]acetyl-CoA, relied on trapping the β-[14C]ketobutyryl-ACP product (14). eFabH was the most active enzyme in this assay, with bFabH2 having about 20% of the activity of eFabH and bFabH1 having 2.5% of the activity of eFabH (Table 1). The filter disc assay is a reliable, sensitive, and rapid method to determine FabH activity (12, 31) but can only be used when a 14C-labeled primer is available. Therefore, we employed a second assay to determine the activity of the enzymes for branched-chain primers based on the incorporation of [2-14C]malonyl-CoA and the separation of products by conformationally sensitive gel electrophoresis and quantitation of product formation by PhosphoImager analysis (12). The conversion of the product to the stable β-hydroxyacyl-ACP was necessary because the β-ketoacyl-ACPs were unstable and were degraded during the electrophoretic separation (12). Thus, saturating concentrations of FabG plus NADPH were included to ensure reduction of all of the β-ketoacyl-ACPs formed to the corresponding stable β-hydroxyacyl-ACPs. When acetyl-CoA was the substrate in this assay, the specific activity measurements were essentially the same as in the filter disc assay (Table 1), indicating that both assays accurately reflect the catalytic properties of the condensing enzymes. An example of the electrophoretic assay system in the analysis of the utilization of isovaleryl-CoA as a primer for the three FabH enzymes is shown in Fig. 3. In this experiment, eFabH was inactive with the isovaleryl-CoA, whereas bFabH2 was more active than bFabH1 (see also Table 1). The band migrating faster than malonyl-ACP in the eFabH experiment was acetyl-ACP, reflecting the malonyl-ACP decarboxylase activity of the condensing enzyme.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificities of E. coli FabH and B. subtilis FabH1 and FabH2

| Substrate | Enzyme activity (nmol/min/mg)a (mean ± SD)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli FabH | B. subtilis FabH1 | B. subtilis FabH2 | |

| Acetyl-CoAb | 465 ± 62 | 24 ± 0.9 | 105 ± 11 |

| Acetyl-CoAa | 494 ± 11 | 14 ± 0.5 | 113 ± 10 |

| Propionyl-CoA | 133 ± 5 | 18 ± 0.8 | 20 ± 1 |

| Butyryl-CoA | 1 ± 0.1 | 8 ± 1 | 29 ± 4 |

| Valeryl-CoA | <1 | 15 ± 0.6 | 34 ± 3 |

| Hexanoyl-CoA | <1 | 14 ± 0.6 | 10 ± 1 |

| Heptanoyl-CoA | <1 | 13 ± 0.6 | 5 ± 0.4 |

| Octanoyl-CoA | <1 | 8 ± 0.5 | <1 |

| Isobutyryl-CoA | <1 | 58 ± 2 | 149 ± 9 |

| Isovaleryl-CoA | <1 | 16 ± 0.8 | 162 ± 5 |

| 2-Methylbutyryl-CoA | <1 | 155 ± 10 | 79 ± 9 |

The specific activities for the condensation of the indicated acyl-CoA substrates (45 μM) were determined with purified His-tag FabH proteins, FabG, and [2-14C]malonyl-CoA by using the assay conditions and electrophoretic analysis to measure product formation described in Materials and Methods.

This specific activity was determined by the filter disc assay and [1-14C]acetyl-CoA as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 3.

Utilization of an isovaleryl-CoA by FabH isoforms. Assays contained E. coli FabH or B. subtilis FabH1 or FabH2, E. coli FabD, FabG, ACP, NADPH, isovaleryl-CoA (iso-C5:0), and [14C]malonyl-CoA as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting β-OH-iso-C7:0-ACP was detected with a PhosphoImager following conformationally sensitive gel electrophoresis in 13% polyacrylamide containing 1.0 M urea. The amount of label incorporated into β-OH-iso-C7:0-ACP was determined by using a PhosphoImager system that was calibrated with a standard curve of [14C]malonyl-CoA that was exposed at the same time as the gel. (A) E. coli FabH; (B) B. subtilis FabH1; (C) B. subtilis FabH2; (D) the specific activities of E. coli FabH, B. subtilis FabH1, and FabH2 calculated from the slopes of the lines obtained from plotting the nanomoles of β-OH-iso-C7:0-ACP per minute versus the protein concentration in the assay. Symbols: ■, E. coli FabH; ●, B. subtilis FabH1; ○, B. subtilis FabH2.

The specific activities for a range of acyl-CoA primers were determined for all three enzymes (Table 1). As reported previously (12), eFabH was most active with acetyl-CoA, had considerably reduced activity (0.2%) with butyryl-CoA, and was inactive with longer chain lengths. Most importantly, we did not detect any activity of eFabH when branched-chain acyl-CoA primers were used. The bFabH1 protein exhibited a low activity with acetyl-CoA but was active with 4- to 8-carbon straight-chain acyl-CoA and all branched-chain acyl-CoAs. The bFabH2 protein was more active than the bFabH1 enzyme with acetyl-CoA, but like bFabH1 it readily utilized 4- and 5-carbon straight-chain acyl-CoAs and the three branched-chain acyl-CoAs tested. Whereas bFabH1 and bFabH2 did not have markedly dissimilar specific activities, bFabH1 did have a slight preference for the anteiso precursor, 2-methylbutyryl-CoA, while bFabH2 was more active with the iso precursors, isobutyryl-CoA and isovaleryl-CoA. These data illustrate that the ability to use branched-chain acyl-CoA primers distinguishes the B. subtilis FabH enzymes from E. coli FabH.

Specificity of other Fab enzymes for branched-chain substrates.

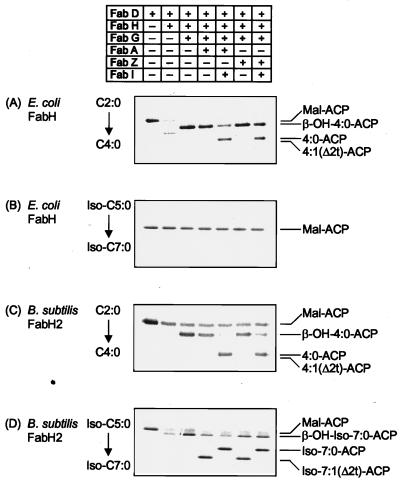

The finding that eFabH does not accept branched-chain primers suggested that the other enzymes in the E. coli fatty acid synthase might also be selective against branched-chain intermediates. This idea was tested by reconstituting one complete round of fatty acid synthesis by using either eFabH or bFabH2 to form the initial intermediates and the other Fab enzymes to complete the cycle (Fig. 4). The control experiment with all E. coli enzymes and acetyl-CoA (Fig. 4A) gave the expected distribution of products at each step and efficient formation of butyryl-ACP (11). As expected, there was no formation of products when eFabH was used as the initiator enzyme and isovaleryl-CoA was used as the primer (Fig. 4B). The bFabH2 enzyme was less active with acetyl-CoA, but nonetheless butyryl-ACP was formed as anticipated (Fig. 4C). Importantly, the E. coli enzymes in conjunction with bFabH2 were able to generate isoheptanoyl-ACP from isovaleryl-CoA (Fig. 4D). These data demonstrated that eFabH selected against branched-chain primers but that the other enzymes in the pathway were able to use either straight-chain or branched-chain intermediates.

FIG. 4.

FabH substrate specificity governs the synthesis of branched-chain fatty acids. A complete cycle of fatty acid synthesis was reconstituted from purified components by using combinations of FabD, FabG, FabI, FabA, or FabZ enzymes (0.2 μg/assay) purified from E. coli and either E. coli FabH (0.2 μg/assay) or B. subtilis FabH2 (0.2 μg/assay), ACP, NADH, NADPH, acetyl-CoA, or isovaleryl-CoA with [14C]malonyl-CoA as the label as described in Materials and Methods. Acetyl-CoA was used as the primer in panels A and C, whereas isovaleryl-CoA was used as a primer in panels B and D. The products were analyzed by conformationally sensitive gel electrophoresis through 13% polyacrylamide gels containing either 0.5 M urea (A and C) or 1.0 M urea (B and D). Products were visualized and quantitated with a PhosphoImager.

One interesting point from these experiments was that the ratios of products from the FabA and FabZ dehydratases were different depending on the nature of the substrate. With the straight-chain 4-carbon intermediates, crotonyl-ACP was a minor component and the β-hydroxyacyl-ACP was predominant as described previously by our laboratory (11, 13). In contrast, when the long-straight-chain (11, 13) or branched-chain (Fig. 4) substrates were used, the enoyl-ACP intermediate was present in greater abundance. Figure 4 is an example of this different product distribution (compare panels C and D), but it was the same regardless of the structure of the branched-chain substrate (data not shown). It will be interesting to determine whether the FabZ component of B. subtilis fatty acid synthase gives rise to a product distribution skewed toward the β-hydroxyacyl-ACP or enoyl-ACP side of the reaction. The answer to this question would have important implications with regard to whether FabI plays the same role in controlling fatty acid biosynthesis in gram-positive bacteria as it does in E. coli (11).

Formation of branched-chain fatty acids in E. coli.

The in vitro enzymology suggested that a branched-chain-specific FabH was necessary and sufficient for the formation of branched-chain fatty acids by type II fatty acid synthase systems. This idea was tested in vivo by the transformation of E. coli SJ53 (panD fadE metB) with constructs that expressed the various FabH proteins followed by the chromatographic analysis of the cellular fatty acid composition (Table 2). The control experiments with the empty vector showed that the cells had the normal composition of straight-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids typical of E. coli. In contrast, transformation of strain SJ53 with plasmids expressing either bFabH1 or bFabH2 resulted in the appearance of branched-chain 17-carbon fatty acids in the cellular lipids. These data illustrate that the substrate specificity of FabH is a key determinant of branched-chain fatty acid synthesis by type II fatty acid synthases.

TABLE 2.

Fatty acid composition of E. coli strains transformed with bfabH1 or bfabH2a

| Plasmid | Wt % fatty acid

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14:0b | 15:0 | 16:1 | 16:0 | Iso17:0 | Cyc17:0c | 18:1 | 18:0 | |

| Control | 3.8 | Trace | 25.5 | 50.4 | —d | 6.5 | 10.9 | 2.7 |

| bfabH1 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 20.6 | 42.9 | 3.3 | 15.1 | 7.6 | 1.9 |

| bfabH2 | 2.8 | Trace | 25.0 | 38.5 | 10.7 | 7.1 | 13.9 | 2.0 |

Strain SJ53 was transformed with pBluescript plasmids that contained no insert (control) or the bFabH1 or bfabH2 genes. The cells were grown on plates containing rich medium, and the fatty acid composition was analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography. The data shown is from a representative experiment. The ranges of values for iso17:0 content were 3.3 to 3.8% for bfabH1 and 9.5 to 10.7% for bfabH2.

Number of carbons atoms:number of double bonds.

The cyclopropane derivative of 16:1.

—, not detected.

DISCUSSION

Our results lead to the conclusion that the substrate specificity of the FabH condensing enzyme is the determining factor in the biosynthesis of branched-chain fatty acids by type II fatty acid synthases. The high degree of specificity of E. coli FabH for acetyl-CoA noted in this work and in previous studies (12, 14, 15, 31) provides a solid rationale for the exclusion of branched-chain acyl-CoA primers and the absence of iso- and anteiso-branched fatty acids in this organism. In contrast, the FabH enzymes from the gram-positive B. subtilis are less active with acetyl-CoA and readily utilize branched-chain acyl-CoA primers. The ability of bFabH1 and bFabH2 to use branched-chain primers correlates with higher activities with straight-chain 4-, 5-, and 6-carbon primers. The substrate specificities of the B. subtilis FabH1 and FabH2 enzymes are consistent with previous data on the incorporation of exogenous branched-chain precursors into cellular fatty acids (16, 18, 19) and the proposed origin of the primers for branched-chain amino acids by a specialized α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex (20, 23). A single FabH protein from Streptomyces glaucescens which also uses both isobutyryl-CoA and butyryl-CoA as primers has been characterized (10). Thus, the FabH proteins from organisms that produce branched-chain fatty acids exhibit a broader substrate specificity than the FabH enzymes from an organism which produces straight-chain fatty acids and is highly selective for acetyl-CoA. The FabH components of the type II polyketide synthases are also the determining factor in primer selectivity in antibiotic synthesis (1).

The other enzymes in the type II fatty acid biosynthetic pathway do not have a significant degree of selectivity for either branched-chain or straight-chain fatty acids. Reconstitution of an elongation cycle in vitro showed that FabG, FabZ, and FabI of E. coli all were capable of utilizing the branched-chain acyl-ACP substrates. This finding was corroborated by the fact that expression of either the B. subtilis FabH1 or FabH2 proteins in E. coli resulted in the production of 17-carbon branched-chain fatty acids. The converse is also true. The expression of B. subtilis fabI complements the phenotype of an E. coli fabI(Ts) mutant and restores normal fatty acid composition, illustrating that the gram-positive FabI is capable of using unsaturated straight-chain enoyl-ACP as well as saturated branched- and straight-chain enoyl-ACP (R. J. Heath and C. O. Rock, unpublished observations).

The broad substrate specificity of the bFabH proteins suggests that the supply of precursors is a significant factor in determining the composition of fatty acids produced by B. subtilis fatty acid synthase. Feeding B. subtilis branched-chain acids increases the levels of the corresponding long-chain branched fatty acids, whereas the addition of butyrate to the medium increased the formation of straight-chain fatty acids (16). The addition of exogenous leucine or valine to cultures of S. glaucescens resulted in a concomitant increase in the relevant branched-chain fatty acid derived from these precursors (29). It was noted previously that the largest component of the branched-chain fatty acid profile was related to the relative size of metabolic pools of α-ketoisocaproate, α-keto-β-methylvalerate, and α-ketoisovalerate (17, 20). These α-keto acids are present at much lower intracellular concentrations than the corresponding amino acids in E. coli, due to the high affinities of the transaminases for the α-keto acids compared to the corresponding amino acids (32). Although pyruvate dehydrogenase will also accept branched-chain α-keto acids as substrates at a low rate, a specialized α-keto acid dehydrogenase is critical for generating the branched-chain acyl-CoA primers for FabH in Bacillus (23).

The physiological significance of two FabH enzymes in B. subtilis is not clear. Other organisms with type II fatty acid synthase systems contain only a single fabH homolog in their genomes. These include E. coli (2), Rickettsia prowazekii (6), Clamydia trachomatis (28), Aquifex aeolicus (8), Helicobacter pylori (30), and Haemophilus influenzae (9). There are no major differences in substrate specificity (straight-chain versus branched, or iso- versus anteiso-branched primers) that clearly distinguish the two Bacillus enzymes, as might have been expected. The bFabH1 protein appears certain to participate in the type II fatty acid synthase system based on its genetic association with a fabF homolog. FabF and FabB are condensing enzymes that carry out the subsequent elongation reactions in fatty acid synthesis, and there is only a single FabF/B homolog in B. subtilis. Analysis of the Bacillus FabF (yjaY) sequence predicted a protein that was 22% identical and 30% similar to E. coli fabF and 21% identical and 30% similar to E. coli fabB. The yjaY open reading frame was located immediately downstream of yjaX, and the two genes appear to form an operon. The organization of the fabH1 (yjaX) and fabF (yajY) genes in a single transcriptional unit argues that these two proteins act in concert in the B. subtilis type II fatty acid synthase. The differential inhibition of branched-chain fatty acid synthesis in relation to straight-chain fatty acid production by thiolactomycin in S. glaucescens may be interpreted as evidence for two FabH enzymes in this organism; however, the similar experiment with B. subtilis did not provide evidence for two mechanisms for initiation (10). It seems likely that fabH1 is a constitutively expressed initiator of fatty acid synthesis and that fabH2 expression may be regulated by environmental or developmental signals to modify membrane fatty acid composition. Alternatively, it is possible that bFabH2 participates in a biosynthetic pathway that is distinct from fatty acid synthesis, for example, the production of a secondary metabolite.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Magdalena Kaminska for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 34496, Cancer Center (CORE) Support Grant CA 21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bao W, Sheldon P J, Hutchinson R. Purification and properties of the Streptomyces peucetius DpsC β-ketoacyl:acyl carrier protein synthase III that specifies the propionate-starter unit for type II polyketide biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9752–9757. doi: 10.1021/bi990751h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner F R, Plunkett G I, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butterworth P H, Bloch K. Comparative aspects of fatty acid synthesis in Bacillus and Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1970;12:496–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corvera S, Czech M P. Direct targets of phosphoinositide 3-kinase products in membrane traffic and signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:442–446. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronan J E, Jr, Rock C O. Biosynthesis of membrane lipids. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtis III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 612–636. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deckert G, Warren P V, Gaasterland T, Young W G, Lenox A L, Graham D E, Overbeek R, Snead M A, Keller M, Aujay M, Huber R, Feldman R A, Short J M, Olsen G J, Swanson R V. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature (London) 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus infuenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han L, Lobo S, Reynolds K A. Characterization of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III from Streptomyces glaucescens and its role in initiation of fatty acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4481–4486. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4481-4486.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heath R J, Rock C O. Enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (fabI) plays a determinant role in completing cycles of fatty acid elongation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26538–26542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heath R J, Rock C O. Inhibition of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) by acyl-acyl carrier protein in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10996–11000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heath R J, Rock C O. Roles of the FabA and FabZ β-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratases in Escherichia coli fatty acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27795–27801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackowski S, Murphy C M, Cronan J E, Jr, Rock C O. Acetoacetyl-acyl carrier protein synthase: a target for the antibiotic thiolactomycin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7624–7629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackowski S, Rock C O. Acetoacetyl-acyl carrier protein synthase, a potential regulator of fatty acid biosynthesis in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7927–7931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneda T. Biosynthesis of branched chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:1229–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneda T. Biosynthesis of branched-chain fatty acids. IV. Factors affecting relative abundance of fatty acids produced by Bacillus subtilis. Can J Microbiol. 1966;12:501–514. doi: 10.1139/m66-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneda T. Incorporation of branched-chain C6-fatty acid isomers into the related long-chain fatty acids by growing cells of Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 1971;10:340–347. doi: 10.1021/bi00778a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaneda T. Steroselectivity in the 2-methylbutyrate incorporation into anteiso fatty acids in Bacillus subtilis mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;960:10–18. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneda T. Iso- and anteiso-fatty acids in bacteria: biosynthesis, function, and taxonomic significance. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:288–302. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.288-302.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature (London) 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oku H, Kaneda T. Biosynthesis of branched-chain fatty acids in Bacillis subtilis. A decarboxylase is essential for branched-chain fatty acid synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18386–18396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rock C O, Cronan J E., Jr Escherichia coli as a model for the regulation of dissociable (type II) fatty acid biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1302:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rock C O, Jackowski S, Cronan J E., Jr . Lipid metabolism in procaryotes. In: Vance D E, Vance J E, editors. Biochemistry of lipids, lipoproteins and membranes. Vol. 31. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Publishing Co.; 1996. pp. 35–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stadtman E R. Preparation and assay of acetyl phosphate. Methods Enzymol. 1955;1:228–232. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stadtman E R. Preparation and assay of acyl-coenzyme A and other thioesters; use of hydroxylamine. Methods Enzymol. 1957;3:931–941. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephens R S, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov R L, Zhao Q, Koonin E V, Davis R W. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subrahmanyam S, Cronan J E., Jr Overproduction of a functional fatty acid biosynthetic enzyme blocks fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1998;180:4596–4602. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4596-4602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomb J-F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Hickey E K, Berg D E, Gocayne J D, Utterback T R, Peterson J D, Kelley J M, Cotton M D, Weidman J M, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Karp P D, Smith H O, Fraser C M, Ventura M A. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature (London) 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsay J-T, Oh W, Larson T J, Jackowski S, Rock C O. Isolation and characterization of the β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III gene (fabH) from Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6807–6814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umbarger H. Biosynthesis of the branched-chain amino acids. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 442–457. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang G-F, Kuriki T, Roy K L, Kaneda T. The primary structure of branched-chain α-oxo acid dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis and its similarity to other α-oxo acid dehydrogenases. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:1091–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willecke K, Pardee A B. Fatty acid-requirement mutant of Bacillus subtilis defective in branched chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:5261–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]