Abstract

Phosphatidylglycerol, the most abundant acidic phospholipid in Escherichia coli, has been considered to play specific roles in various cellular processes and is believed to be essential for cell viability. It is functionally replaced in some cases by cardiolipin, another abundant acidic phospholipid derived from phosphatidylglycerol. However, we now show that a null pgsA mutant is viable, if the major outer membrane lipoprotein is deficient. The pgsA gene normally encodes phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase that catalyzes the committed step in the biosynthesis of these acidic phospholipids. In the mutant, the activity of this enzyme and both phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin were not detected (less than 0.01% of total phospholipid, both below the detection limit), although phosphatidic acid, an acidic biosynthetic precursor, accumulated (4.0%). Nonetheless, the null mutant grew almost normally in rich media. In low-osmolarity media and minimal media, however, it could not grow. It did not grow at temperatures over 40°C, explaining the previous inability to construct a null pgsA mutant (W. Xia and W. Dowhan, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:783–787, 1995). Phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin are therefore nonessential for cell viability or basic life functions. This notion allows us to formulate a working model that defines the physiological functions of acidic phospholipids in E. coli and explains the suppressing effect of lipoprotein deficiency.

Since the discovery of phosphatidylglycerol by Benson and Maruo in 1958 (3), the acidic phospholipid has been found in almost every organism and is believed to play essential roles in various cellular processes, such as SecA protein-dependent translocation of proteins across the membrane and rejuvenation of DnaA protein into an active ATP-bound form in the initiation of oriC DNA replication, based on results obtained mainly from in vitro studies (9, 32).

The Escherichia coli pgsA3 allele encodes a defective phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase with low activity, resulting in cells defective in the major acidic phospholipids, phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin (23). The pgsA mutation is lethal in wild-type cells, while the cls mutations, resulting in reduction of cardiolipin content, affect their growth only slightly (13, 24). Therefore, the lethality and growth arrest phenotype of acidic phospholipid-deficiency caused by pgsA3 and reduced expression of pgsA, which is under the control of the lac promoter, are considered indications of the involvement of the acidic phospholipid in essential cellular functions (9, 11, 12, 32). The lethality is suppressed by the lack of or by certain mutational changes in the major outer membrane lipoprotein (Braun's lipoprotein), which consumes equimolar amounts of phosphatidylglycerol for processing of prolipoprotein, the primary gene product of lpp (2, 31). There are two alternatives to explain the suppression: (i) a drain of the limited acidic phospholipid pool required for certain essential functions in pgsA mutants is relieved by a lack of prolipoprotein or (ii) the limitation causes a harmful accumulation of unprocessed prolipoprotein in the inner membrane (9, 32). The null pgsA30::kan allele, which inactivated pgsA by the insertion of a kanamycin resistance gene (11), was reported not to be suppressed by the lack of the major outer membrane lipoprotein (36). Based on this result, Xia and Dowhan (36) suggested that there must be requirements for the acidic phospholipids even in the presence of the suppressor.

However, in this paper, we present evidence that E. coli null pgsA mutants are viable and grow almost normally, with no detectable phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin, in the presence of the suppressor. Furthermore, the previous inability to construct a null pgsA mutant, concluding in an incorrect notion that phosphatidylglycerol is essential, is explained by the characteristics of the null mutant. The results indicate that the quantitatively major acidic phospholipids, phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin, are not essential for the viability or basic life functions of E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Table 1 summarizes the E. coli K-12 strains used in this study. Strain S300 is a derivative of W3110 with a ksgB1 marker and is wild type with regard to phospholipid synthesis, and S301 is an lpp-2 derivative of W3110 (25). S303 is a pgsA3 derivative of S301 (25), and S330 is the pgsA30::kan derivative we constructed by P1 phage transduction (22) of an S301 recipient (see below). Another set of K-12 strains, JE5512 (Hfr man-1 pps) and JE5513 (JE5512 lpp-2) (2), were also used. Strain MDL12 [pgsA30::kan Φ(lacOP-pgsA+)1 lacZ′ lacY::Tn9] (36) was the gift from William Dowhan. We will deposit our construct of S330 strain with the parental strain in the E. coli genetic stock center after publication of this paper.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| W3110 | λ− IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 rph-1 | Laboratory stock |

| S300 | W3110 ksgB1 | Laboratory stock |

| S301 | W3110 ksgB1 lpp-2 (formerly lpo) | Laboratory stock |

| S303 | S301 pgsA3 uvrC | 25 |

| S330 | S301 pgsA30::kan | This work |

| MDL12 | pgsA30::kan Φ(lacOP-pgsA+)1 lacZ′ lacY::Tn9 | 36 |

| JE5512 | Hfr man-1 pps | 14 |

| JE5513 | JE5512 lpp-2 | 14 |

Media and growth conditions.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (398 mosM/kg) containing 1% tryptone (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), 0.5% yeast extract (Difco), and 1% NaCl and minimal A medium supplemented with 0.02% MgSO4, 0.2% glucose, 0.02% amino acid mixture, and 0.0001% thiamine hydrochloride (110 mosM/kg) were prepared as described previously (22). NBY medium of low osmolarity (108 mosM/kg) (34) and NBY medium supplemented with 1% NaCl (370 mosM/kg) were also used. Kanamycin and chloramphenicol were added, when necessary, to concentrations of 30 mg per liter. The motility test plate of LB medium contained 80 g of gelatin per liter, as described previously (18). Cells were grown at 37°C unless otherwise specified, and growth was monitored with a Klett-Summerson photoelectric colorimeter (no. 54 filter).

Phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase assay.

Phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase in cell extract was assayed by measurement of the CDP-diacylglycerol-dependent incorporation of sn-[U-14C]glycerol-3-phosphate into the chloroform-soluble lipid fraction, as described previously (26). Specific activity is defined as nanomoles of the labeled substrate incorporated per milligram of protein per minute at 37°C.

Phospholipid analysis.

Cells were labeled in NBY medium supplemented with 1% NaCl and with 7.5 μCi of 32Pi/ml for six generations to late stationary phase at 37°C. Lipids were extracted by the method of Ames (1) and separated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates (Silica gel 60; Merck) as described previously (33). The plates were developed first (x dimension) with chloroform-methanol-water (65:25:4 [vol/vol/vol]) and then (y dimension) with chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (65:25:10 [vol/vol/vol]), dried, and exposed to X-ray film for 30 h. After the labeled spots were scraped off the plate, the radioactivities were counted and calculated (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Phospholipid composition of E. coli pgsA mutants

| Strain | Molar percenta

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG | CL | PE | PA | CDP-DG | Others | |

| S301 (pgsA+) | 11.7 | 6.5 | 80.8 | <0.01 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| S303 (pgsA3) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 92.1 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 0.7 |

| S330 (pgsA30::kan) | <0.01 | <0.01 | 90.5 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 2.3 |

Molar percentage of phospholipids, as calculated from the 32Pi radioactivities of spots shown in Fig. 2. Strain S330 was analyzed for two independent transductant clones which gave essentially the same results. Errors in duplicate analyses were less than 3% of each value. PG, phosphatidylglycerol; CL, cardiolipin; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PA, phosphatidic acid; CDP-DG, (d)CDP-diacylglycerol. The detection limit, 0.01%, for the samples of S330 corresponded to 7 cpm.

PCR analysis.

DNA from fresh colonies of the strains to be examined was used as a template for PCR amplification with Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Primer FPPG5 (5′-CCGTCACCATGGAATTTAATATCCCTAC-3′) starts from 8 bases upstream of the initiation codon of pgsA, and antisense primers ASFPPG1 (5′-CCCGAATTCATCAAGCAATCAG-3′) and ASFPPG3 (5′-GTCAGTACTGCAGCCACAAAG-3′) start from 156 bases downstream and 55 bases upstream, respectively, of the stop codon TGA (35). With the primer pair FPPG5 and ASFPPG1, the expected size of the product from the wild-type pgsA gene is 712 bp and that from the pgsA30::kan allele is 1.9 kbp by the insertion of a kan cassette (ca. 1.2 kbp) (11). With primer pair FPPG5 and ASFPPG3, the expected sizes of the products from the wild-type pgsA and the pgsA30::kan alleles are 499 bp and 1.7 kbp, respectively. MDL12 has the pgsA30::kan allele and lacOP-controllable pgsA, but the latter allele has no ASFPPG1 site.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of a null pgsA mutant.

During the course of the construction of a strain whose acidic phospholipid content is controlled by an exogenously added inducer, we transferred by P1 phage transduction the null pgsA30::kan allele of strain MDL12 (36) into lpp-2 mutants with or without a plasmid-borne and araBAD promoter-controllable pgsA gene (unpublished data). The null pgsA allele was constructed by Heacock and Dowhan by inserting a kanamycin resistance gene into a functionally important region of the pgsA gene (11). Unexpectedly, we found that a recipient strain, S301, that did not contain plasmid-borne pgsA, which was included as a negative control, yielded a large number (comparable to those of recipient strains harboring the plasmid-borne pgsA gene) of Kanr transductants, indicating an efficient transfer of the pgsA30::kan allele into the recipient strain, irrespective of the presence of the intact pgsA gene. Since acidic phospholipids were considered essential for cell viability, the emergence of Kanr transductants was rather surprising. Table 2 shows a typical result of P1 transduction, which demonstrated the viable nature of the null (pgsA30::kan) mutant when lpp, the structural gene for the major outer membrane lipoprotein (14), is defective (lpp-2). The table also shows that an unidentified mutation in strain JE5512 that partially suppresses a leaky mutation, pgsA3 (2), did not suppress the lethal nature of the null pgsA. The suppressive effect of the lpp-2 mutation was similarly observed in another lpp-2 mutant (JE5513) with a different genetic background. PCR analysis of three independent null transductants (strain S330) indicated that they all have pgsA30::kan alleles of the same size as that of strain MDL12 (1.9 kbp) and have no wild-type pgsA (0.71 kbp), as assessed with the primer pair FPPG5 (the sense primer at the initiation codon) and ASFPPG1 (the antisense primer at 156 bases downstream from the stop codon) (Fig. 1). With the primer pair FPPG5 and ASFPG3 (the antisense primer within pgsA located 214 bases upstream from ASFPPG1), a 1.7-kbp fragment of the pgsA30::kan allele alone (no DNA fragment of wild-type pgsA) was produced from the null transductants. Strain MDL12 gave DNA fragments (1.7 and 0.5 kbp) corresponding to pgsA30::kan and lacOP-controllable wild-type pgsA contained in MDL12 with the latter primer pair (12, 36).

TABLE 2.

Introduction of the disrupted pgsA allele by P1 phage transductiona

| Recipient | lpp | No. of transductants

|

Frequency (Kanr/Cmr) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanr | Cmr | |||

| S300 | Wild type | 0 | 334 | <0.003 |

| S301 | lpp-2 | 31 | 260 | 0.12 |

| JE5512 | Wild type | 0 | 432 | <0.002 |

| JE5513 | lpp-2 | 73 | 504 | 0.14 |

P1 phage transduction (22) was conducted with strain MDL12 [pgsA30::kan Φ(lacOP-pgsA+)1 lacZ′ lacY::Tn9] (36) as the donor. Thus, the disrupted pgsA gene conferred kanamycin resistance (Kanr) and the lacY gene disrupted by Tn9 conferred chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr), serving as an internal standard to monitor the transduction frequency. Strain S300 is a derivative of strain W3110, and strain S301 is an lpp-2 derivative. Strains JE5512 and JE5513, which have a partial suppressor of pgsA3, were previously described (2). The transduction frequency of the pgsA30::kan marker is low, but the frequencies of the recipient strains with and without plasmid-borne pgsA were essentially the same.

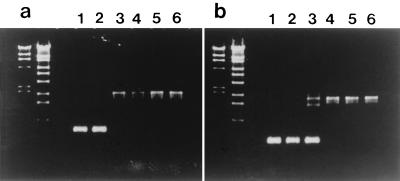

FIG. 1.

PCR analysis of the pgsA alleles of E. coli pgsA mutants. PCR products amplified with Ex Taq DNA polymerase were subjected to 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Lanes 1, W3110; lanes 2, S301; lanes 3, MDL12; lanes 4 to 6, independent clones of the transductants (S330). Primer pairs FPPG5-ASFPPG1 (a) and FPPG5-ASFPPG3 (b) were used. The design and sequences of the primers are described in Materials and Methods. With the former primer pair, the wild-type pgsA allele and the pgsA::kan allele gave products of 0.71 and 1.9 kbp, respectively. With the latter primer pair, the wild-type pgsA and the pgsA::kan alleles gave products of 0.5 and 1.7 kbp, respectively. A DNA fragment of ca. 1.5 kbp which appeared in MDL12 (panel b, lane 3) may be the product of a false annealing of the antisense primer with a site in lacZ′ fused to pgsA (12). The molecular size markers included (two left lanes of each gel) were λ-HindIII digest (23.1, 9.4, 6.6, 4.4, 2.3, 2.0, and 0.56 kbp) and λ-EcoT14 I digest (19.3, 7.7, 6.2, 4.3, 3.5, 2.7, 1.9, 1.5, 0.93, and 0.42 kbp).

Phospholipid biosynthesis and composition of the null pgsA mutant.

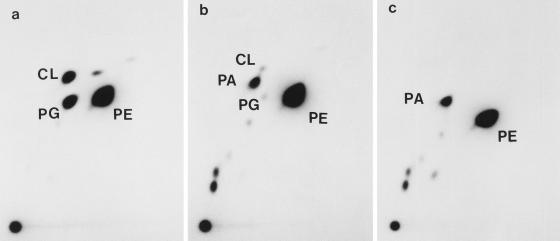

Figure 2 shows autoradiograms of lipid fractions heavily and uniformly labeled with 32Pi. Strain S303 (pgsA3 lpp-2) contained very low but definitely detectable levels of phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin, as previously described (23), but a transductant strain, S330 (pgsA30::kan lpp-2), did not contain detectable levels of these acidic phospholipids. We calculated phospholipid compositions from the radioactivities of spots of these autoradiograms (Table 3); strain S303 contained phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin at 0.3 and 0.2 molar percent, respectively, of the total phospholipids, whereas in strain S330 we did not detect these acidic phospholipids at all. In strains S303 and S330, biosynthetic precursors for the major phospholipids, phosphatidic acid and (d)CDP-diacylglycerol, accumulated. Hence, the phospholipid polar head group composition of the mutant was 4.0% phosphatidic acid, 3.2% CDP-diacylglycerol, 91% phosphatidylethanolamine, and others. Despite these drastic abnormalities in polar head group composition, the total phospholipid contents in pgsA null mutants were not much different from that of the wild-type strain (150 nmol of lipid phosphorus per mg of cellular protein in both S303 and S330 compared to 180 nmol in S301). The activity of phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase was undetectable in strain S330 (below the detection limit of 0.01 nmol of sn-[U-14C]glycerol 3-phosphate incorporated into chloroform-soluble products per min per mg of protein at 37°C, or less than 0.3% of that of the wild-type strain, W3110). The activity of strain S303 (pgsA3) was 0.22 nmol per min per mg of protein. These findings strongly suggested that the null pgsA mutants do not contain phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin at all, although we cannot exclude the possibility that very low levels of these lipids, at the most 0.01% of the total phospholipids or a few thousand molecules per cell (32), are present in the null mutants, satisfying the absolute requirements, if any, for the lipids.

FIG. 2.

Autoradiograms of 32P-labeled phospholipids of pgsA mutants. Cells of E. coli S301 (wild type) (a), S303 (pgsA3) (b), and S330 (pgsA30::kan) (c) were grown at 37°C in NBY medium supplemented with 1% NaCl in the presence of 7.5 μCi of 32Pi/ml for six generations (to the late-exponential growth phase). The lipids were extracted and separated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (Silica gel 60; Merck) as described previously (34). After the preparation of autoradiograms, the spots were scraped off the plates for measurement of their radioactivities (Table 3). CL, cardiolipin; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PA, phosphatidic acid; PG, phosphatidylglycerol.

Theoretically, phosphatidylglycerol may be formed in the null pgsA mutant by one or both of the following mechanisms: (i) through a somehow enzymologically active gene product directed by the disrupted pgsA gene and (ii) as a side reaction product of an enzyme other than phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase. The former possibility would be excluded if a null mutant can be constructed by deletion of the entire pgsA gene, as was done in the case of the cls gene (24), instead of an insertion into the gene, as was used in the present mutant. The latter side reaction might be catalyzed by phosphatidylserine synthase, since a substantially purified preparation of this enzyme was shown to catalyze, though very slowly, the formation of phosphatidylglycerol or phosphatidylglycerophosphate when the substrate serine was replaced by glycerol or sn-glycerol 3-phosphate, respectively (20). To suggest the side reaction more strongly, a further examination with a phosphatidylserine synthase preparation purified from a pgsA null mutant will be needed.

Phenotypes of the null pgsA mutant.

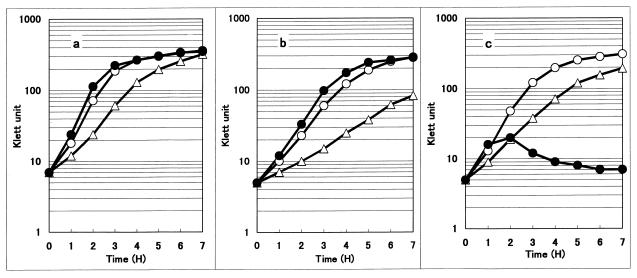

Despite the apparent absence of the major acidic phospholipids, cells of the null pgsA mutant grew almost normally at both 30 and 37°C in a rich LB medium (Fig. 3). However, they did not grow at higher temperatures: the turbidity increase ceased in 2 h when the cells were shifted from 37 to 40°C and more rapidly when they were shifted to 42°C (Fig. 3c). Two hours after the temperature shift to 42°C, the culture turbidity began to decrease. The plating efficiency of the null mutants at 42°C on LB plates was 10−5 relative to that at 37°C. This temperature sensitivity of the null mutants explains the previous inability to cure a temperature-sensitive covering plasmid (bearing the wild-type pgsA gene) in a pgsA30::kan lpp-2 double mutant at a high temperature, thus leading to the incorrect conclusion that phosphatidylglycerol was essential (36). In order to cure the covering pgsA+ plasmid, Xia and Dowhan (36) raised the temperature to 42°C. This treatment should have hampered the growth and colony formation of the pgsA30::kan lpp-2 double mutant, thus yielding no viable colonies. Hence, they were led to the incorrect notion that the pgsA gene was not cured, i.e., that phosphatidylglycerol was indispensable.

FIG. 3.

Growth characteristics of E. coli pgsA mutants. Cells of E. coli S301 (wild type) (a), S303 (pgsA3) (b), and S330 (pgsA30::kan) (c) were grown in LB medium at 37°C to Klett 5 to 7. They were cultured further at 37°C (○) or transferred to 30 (▵) or 42°C (●), and Klett units were measured every hour.

The temperature sensitivity of the null mutant might suggest that E. coli has an essential function(s) which requires phosphatidylglycerol and/or cardiolipin specifically at temperatures above 40°C. The temperature-sensitive nature of the null mutant can be suppressed by an additional mutation (K. Matsumoto et al., unpublished results). At low temperatures, on the other hand, the pgsA3 mutant (S303) grew more slowly (Fig. 3b). The null mutant, S330, however, grew well at low temperatures (Fig. 3c), showing another difference of its growth characteristics from those of the pgsA3 mutant. The null mutants were also unable to grow in media with low osmolarities, such as NBY medium (108 mosM/kg) (34), similar to the characteristics described for pgsA3 mutants, which did not grow in low-osmolarity media (2). Addition of 1% NaCl to the NBY medium suppressed the growth defect by raising the osmolarity to 370 mosM/kg. These phenomena may be related to the function of membrane-derived oligosaccharides.

The greatest drain of the phosphatidylglycerol pool is the synthesis of membrane-derived oligosaccharides (MDO). MDO significantly contribute to the maintenance of the osmolarity of the periplasm when E. coli cells are cultivated in low-osmolarity media (17). In pgsA3 mutants, only reduced amounts of MDO are modified by phosphatidylglycerol-derived phosphoglycerol (23), and therefore, in the complete absence of phosphatidylglycerol a defective MDO lacking phosphoglycerol substituents is probably produced. The defective MDO may not satisfactorily contribute to the maintenance of the osmolarity of the periplasmic space, since a lack of phosphoglycerol substituents loses three net negative charges and freely dissociable monovalent cations, which neutralize the negative charges. This may account for the impaired growth in low-osmolarity media of pgsA mutants, which have defective envelopes lacking cross-bridges between murein and the outer membrane due to their lpp-2 background, though lpp+ cells lacking MDO show little growth impairment (17).

The null pgsA mutant showed several other abnormalities. Minimal A medium with amino acid supplements (110 mosM/kg) did not support the growth of the mutant, irrespective of the addition of 1% NaCl, indicating that the mutant requires for normal growth not only an appropriate osmolarity of the medium but also an unidentified factor(s) that is contained in broth media. The null mutants were nonmotile (data not shown), as was the pgsA3 mutant (25), suggesting that the expression of the flagellar master operon, flhDC, is repressed by the acidic-phospholipid deficiency (15, 18) through an unknown mechanism.

Nonessential nature of the major acidic phospholipids.

From the present observation that the major acidic phospholipids are absent in null pgsA mutants, we reach a tentative conclusion that these lipids are not essential for the viability of E. coli cells. This notion, together with the previous observations, now allows us to formulate a working model for the physiological roles of acidic phospholipids in E. coli. The roles are grouped into two categories: (i) headgroup-specific phospholipids as the substrates of enzymatic reactions, which are dispensable if the reaction products are dispensable, and (ii) acidic phospholipids, which are replaceable by other phospholipids with net negative charges. These two groups of putative functions will be discussed in some detail below.

Suppression by lipoprotein deficiency.

The lpp gene product is dispensable (14), but it is absolutely related to the viability of pgsA mutants (2) (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Among the headgroup-specific functions, the maturation of the lpp gene product, prolipoprotein, which consumes equimolar amounts of phosphatidylglycerol (31), is the only exception. During the maturation of prolipoprotein, it first receives the diacylglycerol moiety of phosphatidylglycerol on the Cys-21 residue, rendering it susceptible to signal peptidase II (31). In the cells lacking phosphatidylglycerol, the modification should be impaired, and unmodified prolipoprotein seems to remain in the inner membrane, probably because of defective translocation of prolipoprotein due to the lack of phosphatidylglycerol (8, 38). Recently, Yakushi et al. (37) indicated that the inner membrane accumulation of prolipoprotein per se is not lethal but that a covalent linking between the inner membrane and peptidoglycan through the COOH-terminal lysine of the prolipoprotein is lethal, presumably because cell surface integrity is disrupted. Accordingly, we assume that the reason for the lethality due to the lack of phosphatidylglycerol in lpp+ cells is a disruption of cell envelope integrity by means of a covalent linking of peptidoglycan and the inner membrane through the unmodified prolipoprotein accumulated in the membrane.

Functional replacement with other acidic phospholipids.

As to the functions of phospholipids that require only net negative charges, the accumulation of phosphatidic acid in pgsA mutants (Table 2) should be important for cell viability: functional replacement of phosphatidylglycerol with other acidic phospholipids, including phosphatidic acid, has been described for several peripheral membrane protein functions in vitro (5, 9, 10, 19, 29, 32). One example is the in vitro promotion by acidic phospholipids of the release of ADP from DnaA protein, by which an inactive ADP form of the initiator protein in the oriCDNA replication rejuvenates into an active ATP-bound form (5, 10). The physiologically important states of phospholipids have been shown to be those in the fluid phase (i.e., above the transition temperature) and a negatively charged headgroup, such as phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylserine, and ganglioside GM1. DnaA protein appears to interact with the negatively charged surface of the membrane by a hydrophobic side of a certain helical-wheel region of this protein (10). As described for SecA (4), DnaA protein may partly insert into the inner membrane after recognizing a domain of several negatively charged headgroups on the surface of the membrane (9). Even if phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin are present at levels below the detectable limit (less than 0.01% of total phospholipids or a few thousand molecules per cell) in pgsA30::kan lpp-2 mutants, these amounts seem to be too small to provide DnaA protein with enough headgroups of phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin at the membrane surface (9). Most probably with the phosphatidic acid accumulated in the null mutant (4.0% of the total phospholipids [Table 3]), the initiation of DNA replication should take place, since the null mutants, with no phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin, grew almost normally. Hence, the lethality and growth arrest phenotype of the lpp+ cells with reduced phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin (2, 12) should not be linked to the suggested inability to initiate DNA replication (36).

The requirement for phosphatidylglycerol in the process of SecA protein-dependent translocation of proteins across the inner membrane (8) is indeed satisfied in vitro by other anionic phospholipids (cardiolipin, phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylinositol, or phosphatidylethanol), indicating that the negative charges of the headgroups of phospholipids rather than other headgroup properties are the primary factors for the stimulation of translocation (4, 19). However, substitution with phosphatidic acid may not be so effective for translocation in vivo, since in vivo translocation of precursor proteins of OmpA and PhoE is retarded in pgsA3 cells (8), which contain phosphatidic acid at a high level (3.8% of the total phospholipids [Table 3]) (8, 19).

Phosphatidylserine synthase activity in vitro has been shown to depend considerably on negatively charged phospholipids (29), in corroboration of the cross-feedback model proposed by Shibuya and Matsumoto (21, 32), which explains the regulation of the balanced membrane phospholipid composition through modulation of phosphatidylserine synthase activity by the fraction of negatively charged phospholipids on the membrane. Phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, cardiolipin, and phosphatidic acid also enhance the activity in vitro (almost equally, but phosphatidic acid is the most prominent) (29). The in vivo activity, examined as the rate of phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis, is, however, considerably lower in the pgsA3 cells (30), which obviously have high levels of phosphatidic acid, suggesting that the phosphatidylserine synthase activity in vivo may not be fully recovered with the phosphatidic acid accumulated in the mutant.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, disruption of the PGS1 gene, which encodes phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase, is not lethal to cells but does seriously compromise the mitochondrial functions, indicating that phosphatidylglycerol and/or cardiolipin is indispensable for the organelle (6). Interruption of the CLS1 gene results in the disappearance of cardiolipin, but mitochondrial functions are not grossly perturbed (7), as with the E. coli cls disruption (13, 24). For yeast, either (i) phosphatidylglycerol but not cardiolipin is essential or (ii) one of these two major acidic phospholipids is essential and they functionally substitute for each other. A PGS1 mutant of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells has shown that phosphatidylglycerol and/or cardiolipin plays a critical role in mitochondrial structure and function, although the defect in the mutant cannot be attributed to the lack of either phospholipid (16, 27, 28). These phenotypes of CHO mutants are quite similar to those of yeast but are in contrast to those of E. coli revealed in the present study. Both phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin are nonessential for cell viability or basic life functions in E. coli; an accumulated biosynthetic precursor, phosphatidic acid, is most probably playing a crucial role for the cell. This notion at the same time strongly suggests the substitutable nature of the biological functions of these phospholipids in the membrane and may overturn many current concepts in the area. Further studies with the present mutant system should be useful for an understanding of the biological functions of phospholipids in the membrane.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William Dowhan for the kind gift of the MDL12 strain. We also thank Yasuko Yokoyama and Masayuki Igawa for their help with experiments and Hiroshi Hara and Hiroshi Matsuzaki for critical discussions.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames G F. Lipids of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli: structure and metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:833–843. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.3.833-843.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai Y, Katayose Y, Hikita C, Ohta A, Shibuya I. Suppression of the lethal effect of acidic-phospholipid deficiency by defective formation of the major outer membrane lipoprotein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6867–6869. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6867-6869.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson A A, Maruo B. Plant phospholipids. I. Identification of the phosphatidylglycerol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1958;27:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breaking E, Hemel R A, Korce-Pool G, de Kruijff B. SecA insertion into phospholipids is stimulated by negatively charged lipids and inhibited by ATP: a monolayer study. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1119–1124. doi: 10.1021/bi00119a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castuma C E, Crooke E, Kornberg A. Fluid membrane with acidic domains activate DnaA, the initiator protein of replication in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24665–24668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang S C, Heacock P N, Clancey C J, Dowhan W. The PEL1 gene (renamed PGS1) encodes the phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9829–9836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang S C, Heacock P N, Mileykovskaya E, Voelker D R, Dowhan W. Isolation and characterization of the gene (CLS1) encoding cardiolipin synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14933–14941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vrije T, de Swart R L, Dowhan W, Tommassen J, de Kruijff B. Phosphatidylglycerol is involved in protein translocation across Escherichia coli inner membranes. Nature (London) 1988;334:173–175. doi: 10.1038/334173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowhan W. Molecular basis for membrane phospholipid diversity: why are there so many lipids? Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:199–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garner J, Crooke E. Membrane regulation of the chromosomal replication activity of E. coli DnaA requires a discrete site on the protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:2313–2321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heacock P N, Dowhan W. Construction of a lethal mutation in the synthesis of the major acidic phospholipids of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:13044–13049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heacock P N, Dowhan W. Alteration of the phospholipid composition of Escherichia coli through genetic manipulation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14972–14977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiraoka S, Matsuzaki H, Shibuya I. Active increase in cardiolipin synthesis in the stationary growth phase and its physiological significance in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:221–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80807-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirota Y, Suzuki H, Nishimura Y, Yasuda S. On the process of cellular division in Escherichia coli: a mutant of E. coli lacking a murein-lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:1417–1420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.4.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue K, Kishimoto A, Suzuki M, Matsuzaki H, Matsumoto K, Shibuya I. Suppression of the lethal effect of acidic-phospholipid deficiency in Escherichia coli by Bacillus subtilis chromosomal locus ypoP. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1998;62:540–545. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawasaki K, Kuge O, Chang S C, Heacock P N, Rho M, Suzuki K, Nishijima M, Dowhan W. Isolation of a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cDNA encoding phosphatidyl glycerophosphate (PGP) synthase, expression of which corrects the mitochondrial abnormalities of a PGP synthase-defective mutant of CHO-K1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1828–1834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy E P. Membrane-derived oligosaccharides. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1064–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitamura E, Nakayama Y, Matsuzaki H, Matsumoto K, Shibuya I. Acidic phospholipid deficiency represses the flagellar master operon through a novel regulatory region in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1994;58:2305–2307. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusters R, Dowhan W, de Kruijff B. Negatively charged phospholipids restore prePhoE translocation across phosphatidylglycerol-depleted Escherichia coli inner membranes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8659–8662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson T J, Dowhan W. Ribosomal-associated phosphatidylserine synthetase from Escherichia coli: purification by substrate-specific elution from phosphocellulose using cytidine 5′-diphospho-1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5212–5218. doi: 10.1021/bi00669a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto K. Phosphatidylserine synthase from bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1348:214–227. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyazaki C, Kuroda M, Ohta A, Shibuya I. Genetic manipulation of membrane phospholipid composition in Escherichia coli: pgsA mutants defective in phosphatidylglycerol synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7530–7534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishijima S, Asami Y, Uetake N, Yamagoe S, Ohta A, Shibuya I. Disruption of the Escherichia coli cls gene responsible for cardiolipin synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:775–780. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.775-780.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishino T, Kitamura E, Matsuzaki H, Nishijima S, Matsumoto K, Shibuya I. Flagellar formation depends on membrane acidic phospholipids in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1993;57:1805–1808. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohta A, Waggoner K, Radominska-Pyrek A, Dowhan W. Cloning of genes involved in membrane lipid synthesis: effect of amplification of phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:552–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.2.552-562.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtsuka T, Nishijima M, Akamatsu Y. A somatic cell mutant defective in phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase, with impaired phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22908–22913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohtsuka T, Nishijima M, Suzuki K, Akamatsu Y. Mitochondrial dysfunction of a cultured Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant deficient in cardiolipin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22914–22919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rilfors L, Niemi A, Haraldsson S, Edwards K, Andersson A-S, Dowhan W. Reconstituted phosphatidylserine synthase from Escherichia coli is activated by anionic phospholipids and micelle-forming amphiphiles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1438:281–294. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saha S K, Nishijima S, Matsuzaki H, Shibuya I, Matsumoto K. A regulatory mechanism for the balanced synthesis of membrane phospholipid species in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1996;60:111–116. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sankaran K, Wu H C. Lipid modification of bacterial prolipoprotein. Transfer of diacylglycerol moiety from phosphatidylglycerol. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19701–19706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibuya I. Metabolic regulations and biological functions of phospholipids in Escherichia coli. Prog Lipid Res. 1992;31:245–299. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(92)90010-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibuya I, Miyazaki C, Ohta A. Alteration of phospholipid composition by combined defects in phosphatidylserine and cardiolipin synthases and physiological consequences in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:1086–1092. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.1086-1092.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibuya I, Yamagoe S, Miyazaki C, Matsuzaki H, Ohta A. Biosynthesis of novel acidic phospholipid analogs in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:473–477. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.473-477.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Usui M, Sembongi H, Matsuzaki H, Matsumoto K, Shibuya I. Primary structures of the wild-type and mutant alleles encoding the phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3389–3392. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3389-3392.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia W, Dowhan W. In vivo evidence for the involvement of anionic phospholipids in initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:783–787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yakushi T, Tajima T, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H. Lethality of the covalent linkage between mislocalized major outer membrane lipoprotein and the peptidoglycan of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2857–2862. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2857-2862.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, Dalgarno L, Wu H C. Deletion of internal twenty-one amino acid residues of Escherichia coli prolipoprotein does not affect the formation of the murein-bound lipoprotein. FEBS Lett. 1992;311:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]