Introduction

Postmastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) for node-positive breast cancer improves locoregional control and disease-free survival.1 Accurate daily delivery is a crucial tenet of radiation therapy to achieve superior results. Huntington disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant incurable neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive motor dysfunction, psychiatric disturbances, and cognitive decline. Patients commonly develop chorea, an involuntary, dance-like movement that affects the whole body. The typical age of onset for HD is approximately 35 to 44 years.2,3 The median survival time after onset of motor symptoms is approximately 15 to 18 years.2 In this article, we report a case of a woman with a diagnosis of node-positive breast carcinoma in the setting of HD.

Case Presentation

A 42-year-old premenopausal woman self-palpated a left breast mass. Her medical history was significant for HD, which was diagnosed 3 years earlier after a family member tested positive. At first, the patient was asymptomatic but eventually established care with neurology at the onset of mild choreiform movements and difficulty with daily activities. She was initially not started on any medication for symptomatic management for her chorea, given her personal aversion to taking medication and concern about potential adverse effects.

Diagnostic imaging revealed multicentric abnormal masses with suspicious axillary lymphadenopathy. Core needle biopsy of the breast mass and node confirmed Nottingham grade 2, Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor-positive, and HER2/neu-negative invasive ductal carcinoma metastatic to an axillary node. Staging studies were negative for distant metastasis. The clinical prognostic stage was IIA (cT3 N1 M0).

The breast cancer multidisciplinary team recommended primary surgery, with the final pathology guiding decision-making for adjuvant chemotherapy. Postmastectomy radiation therapy was recommended given the size of the breast mass and axillary metastasis. Genetic testing was performed and was negative for deleterious mutations. After discussion regarding surgical options including reconstruction, the patient decided she would like to minimize recovery time and risk of complications. The team also felt radiation planning would be optimized without immediate reconstruction.

A modified radical mastectomy was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 1. Pathology demonstrated multiple foci of invasive carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ spanning 70 mm. One of 8 axillary lymph nodes was positive with a 16-mm tumor deposit and extracapsular extension. Final staging was pathologic stage IIB (pT2 N1 M0).

The Oncotype Dx recurrence score was 20, indicating a 17% risk of a distant recurrence in 9 years with hormone therapy alone. Given the patient's concerns about chemotherapy-related neurotoxicity and exacerbation of her neurocognitive issues, chemotherapy was omitted.

Postoperatively, in a multidisciplinary fashion with radiation oncology and neurology leading, we discussed options including daily anesthesia, medications, and nonmedical methods. Discussions also included assessing competing risks of breast cancer recurrence and treatment toxicities in the setting of HD. Furthermore, considering the patient's young age and her pathologic features, the treatment team felt she was likely to experience a breast cancer event of some type during her life span.

With these factors in mind, PMRT was recommended using a combination of medications and nonmedical approaches to reduce the locoregional risk of recurrence, followed by ovarian suppression and hormone therapy.

Discussion

The benefits of PMRT in those with nodal disease is well established.1 A meta-analysis of individual patient data by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists Group compared the risk of recurrence and breast cancer mortality among women who underwent mastectomy with or without adjuvant postmastectomy radiation. All women had some type of axillary surgery, with axillary dissection defined as ≥10 lymph nodes removed and axillary sampling defined as <10 lymph nodes removed. All patients were enrolled in trials that included the chest wall, supraclavicular or axillary fossa (or both), and internal mammary nodes. Among patients with node-positive disease, 19% of those with unirradiated axillary dissection and 29% of those unirradiated with axillary sampling experienced a locoregional recurrence before a distant metastatic event. The relative risk (RR) reduction for overall recurrence was greater for the axillary sampling group (RR, 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.66) compared with the axillary dissection group (RR, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-0.83). Given that our patient had 8 lymph nodes removed, she would presumably derive a significant benefit from PMRT. In the same study, a smaller number of women (n = 318) underwent axillary dissection resulting in a single positive node and some type of adjuvant systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or both). Locoregional recurrence was significantly higher in the unirradiated group (17.8% vs 2.3%; P < .00001).4

The challenge we faced in this case was the inability to immobilize the patient for daily radiation therapy owing to her choreiform movements. Furthermore, during subsequent visits with the patient, it became clear that as she became more anxious, the choreiform movements became more erratic and more difficult to control.

Therefore, the patient was initially started on a very low dose of olanzapine, 1.25 mg at bedtime. The dose was gradually titrated up during the course of 4 months to 5 mg daily. During this time, there were concerns raised regarding the protracted delay to starting radiation therapy. The patient was thus started on monthly Lupron injections while her olanzapine was being titrated. The patient started to exhibit acceptable movement regulation at a 5-mg daily dose.

To make up for the treatment delay, minimize the logistical challenge of daily radiation therapy, and encourage adherence to daily therapy, hypofractionated radiation therapy was recommended. There are more than 2 decades of data solidifying the role of hypofractionated radiation therapy in the treatment of patients with early-stage breast cancer.5,6 Not only has this accelerated course been shown to yield less acute and chronic toxic effects to normal tissues, but it has also shown excellent equivalent locoregional control compared with a standard protracted regimen. The total recommended dose was 4256 cGy over 16 daily treatments.

Radiation therapy was planned to target the left chest wall and low axillary nodes using high tangential fields to encompass the level 1 to 2 axillary nodes. Pathology confirmed 1 positive sentinel lymph node without extracapsular extension and 7 additional negative sentinel nodes. Several studies have suggested omitting regional nodal irradiation for low-burden nodal disease, because regional recurrences are extremely rare events in this cohort.7 Furthermore, data have shown higher rates of upper extremity lymphedema with the use of comprehensive nodal irradiation, which leads to a more restrictive range of motion.8 These toxic effects would inevitably worsen the patient's already compromised quality of life.

Because the lesion was left-sided, it was imperative that we achieve precise daily positioning to optimally target the high-risk tissues with minimal exposure to the underlying organs, including the heart and left lung. Several studies have shown increased cardiac toxic effects from breast cancer radiation therapy. The increase is proportional to the mean dose to the heart starting within a few years after exposure.9

For simulation, we used an alpha cradle and a breast board for immobilization. We also used relaxation techniques, guided imagery, and music during the patient's radiation therapy to attenuate anxiety during daily treatments.10

The radiation therapy used a 3-dimensional conformal technique with a daily 5-mm chest wall bolus. Treatment was delivered using 6 MV photons with segments to improve dose homogeneity. Given the patient's inability to perform deep inspiration breath hold, the fields were designed with a 5-mm margin around the heart. V90 coverage for the level 1 and 2 axillae were 100% and 90.5%, respectively. The mean heart dose was 111.1 cGy. The ipsilateral lung volume receiving ≥ 20Gy was 14.8%, ipsilateral lung receiving ≥ 10Gy was 21.0%, and receiving ≥ 5Gy was 30.8%. Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic11 data were used as a guideline for heart and ipsilateral lung tolerances.

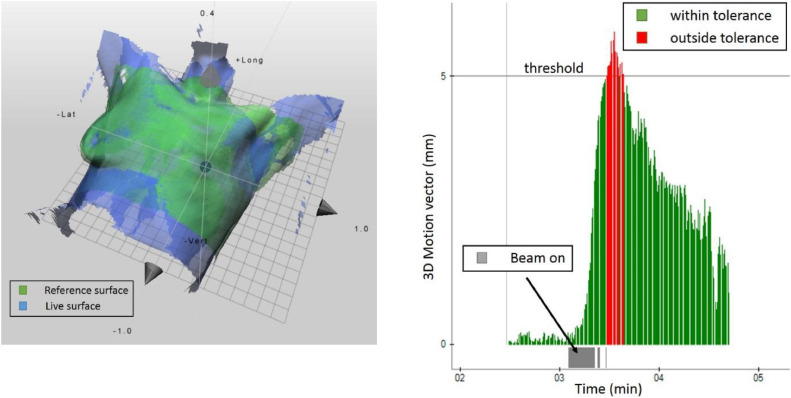

For patient positioning and monitoring, we used surface-guided radiation therapy (SGRT), which uses nonionizing near-visible light to image the patient's external contour. This has been shown to significantly reduce overall setup errors for the breast compared with setup with subcutaneous tattoos12 and to improve patient safety.13 Surface-guided radiation therapy is a nonionizing image guidance technology that acts as a “virtual immobilization” device without having to physically constrain the patient in the treatment position. It was particularly useful for this patient's case because it generally speeds up patient setup, has the capability to monitor the patient's position and movements in real time during treatment, and can automatically shut off the treatment beam if a predetermined positional threshold is reached.14 Additionally, the patient was provided visual biofeedback capability during her daily radiation therapy delivery, which allowed her to tolerate the daily treatments and reproduce her treatment position accurately. Daily posttreatment SGRT documents were generated and reviewed to confirm accurate positioning (Fig. 1). The patient completed radiation therapy without breaks and developed only grade 1 skin toxic effects.

Fig. 1.

Left: Patient setup with surface-guided radiation therapy. Right: Snippet from the monitoring report. Shortly after the beam turned on at approximately 3 minutes, sudden patient movement took place. Once the predetermined motion threshold of 5 mm was reached, the motion vector turned red and the beam automatically shut off.

Conclusion

Preexisting comorbidities contribute additional challenges when effectively treating malignancies. Huntington disease uniquely adds an additional layer of complexity to daily radiation therapy, because immobilization and accuracy of daily treatment delivery become problematic. This case highlights the benefits of thoughtful and considerate discussion among the multidisciplinary oncology team, including neurology, as well as state-of-the-art radiation techniques to deliver effective breast cancer treatment in the setting of symptomatic HD.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: Authors have no disclosures to declare.

References

- 1.Recht A, Comen EA, Fine RE, et al. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: An American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology focused guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4431–4442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caron NS, Wright GEB, Hayden MR. Huntington disease. Available at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1305/. Accessed October 23, 1998.

- 3.Early Breast Cancer Trialists Group Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:2127–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60488-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caron NS, Dorsey ER, Hayden MR. Therapeutic approaches to Huntington disease: From the bench to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:729–750. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whelan T, Pignol J, Levine M. Long-term results of hypofractionated radiation therapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:513–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The START Trialists’ Group The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) Trial B of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1098–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow M, Van Zee K, Patil S. Axillary dissection and nodal irradiation can be avoided for most node-positive Z0011-eligible breast cancers: A prospective validation study of 793 patients. Ann Surg. 2017;266:457–462. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelan T, Olivotto I, Parulekar W. Regional nodal irradiation in early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:307–316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darby S, Ewertz M, McGale P. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:987–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:194–232. doi: 10.3322/caac.21397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentze S, Constine L, Deasy J. Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC): An introduction to the scientific issues. IJROBP. 2010;76:S3–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanley D, McConnell KA, Kirby N, et al. Comparison of initial patient setup accuracy between surface imaging and three-point localization: A retrospective analysis. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2017;18:58–61. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Hallaq H, Batista V, Kügele M, Ford E, Viscariello N, Meyer J. The role of surface-guided radiation therapy for improving patient safety. Radiother Oncol. 2021;163:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiant D, Wentworth S, Maurer J, Vanderstraeten C, Terrell J, Sintay B. Surface imaging-based analysis of intrafraction motion for breast radiotherapy patients. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2014;15:4957. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v15i6.4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]