ABSTRACT

Mobile genetic elements contribute to the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria by enabling the horizontal transfer of acquired antibiotic resistance among different bacterial species and genera. This study characterizes the genetic backbone of blaGES in Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. isolated from untreated hospital effluents. Plasmids ranging in size from 9 to 244 kb, sequenced using Illumina and Nanopore platforms, revealed representatives of plasmid incompatibility groups IncP6, IncQ1, IncL/M1, IncFII, and IncFII-FIA. Different GES enzymes (GES-1, GES-7, and GES-16) were located in novel class 1 integrons in Aeromonas spp. and GES-5 in previously reported class 1 integrons in Klebsiella spp. Furthermore, in Klebsiella quasipneumoniae, blaGES-5 was found in tandem as a coding sequence that disrupted the 3′ conserved segment (CS). In Klebsiella grimontii, blaGES-5 was observed in two different plasmids, and one of them carried multiple IncF replicons. Three Aeromonas caviae isolates presented blaGES-1, one Aeromonas veronii isolate presented blaGES-7, and another A. veronii isolate presented blaGES-16. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis revealed novel sequence types for Aeromonas and Klebsiella species. The current findings highlight the large genetic diversity of these species, emphasizing their great adaptability to the environment. The results also indicate a public health risk because these antimicrobial-resistant genes have the potential to reach wastewater treatment plants and larger water bodies. Considering that they are major interfaces between humans and the environment, they could spread throughout the community to clinical settings.

IMPORTANCE In the “One Health” approach, which encompasses human, animal, and environmental health, emerging issues of antimicrobial resistance are associated with hospital effluents that contain clinically relevant antibiotic-resistant bacteria along with a wide range of antibiotic concentrations, and lack regulatory status for mandatory prior and effective treatment. blaGES genes have been reported in aquatic environments despite the low detection of these genes among clinical isolates within the studied hospitals. Carbapenemase enzymes, which are relatively unusual globally, such as GES type inserted into new integrons on plasmids, are worrisome. Notably, K. grimontii, a newly identified species, carried two plasmids with blaGES-5, and K. quasipneumoniae carried two copies of blaGES-5 at the same plasmid. These kinds of plasmids are primarily responsible for multidrug resistance among bacteria in both clinical and natural environments, and they harbor resistant genes against antibiotics of key importance in clinical therapy, possibly leading to a public health problem of large proportion.

KEYWORDS: ESBL, carbapenemase, integrons, MLST, multireplicons

INTRODUCTION

Horizontal gene transfer through mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as transposons (Tns), insertion sequences (ISs), and integrons (Ins), plays an important role in spreading antimicrobial resistance, a significant global threat to public health, animals, and the environment. The most clinically significant antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) are usually located on different MGEs that can move intracellularly or intercellularly. In hospital effluents, the presence of diverse selection pressures combined with a high concentration of pathogenic/commensal microbes creates favorable conditions for the transfer of ARGs and the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (1).

Interactions between MGEs contribute to the rapid evolution of diverse multidrug-resistant pathogens in antimicrobial chemotherapy. ISs and Tns are discrete DNA segments that can carry resistance genes to genetic locations in the same or different DNA molecules within a single cell. Integrons harbored by plasmids, Tns, and other mobile structures are called “mobile integrons” (MIs) because MGEs promote their dissemination. Therefore, special attention has been given to MIs from natural environments to gather information on their ecology and diversity and understand their role in bacterial adaptation (2).

Integrons are genetic systems that allow bacteria to capture and express gene cassettes. They typically consist of an intI gene encoding an integrase that catalyzes the incorporation or excision of gene cassettes by site-specific recombination, a recombination site attI, and one or two promoters responsible for the expression of inserted gene cassettes. Several promoter variants that vary in strength have been identified, and integrons with weaker promoters often have higher excision activity of integrase (3).

GES-type β-lactamases are rarely encountered. To date, 51 variants have been described (http://bldb.eu/, last updated on 4 June 2022) (4), of which 17 have carbapenemase-hydrolyzing activity due to their amino acid substitutions (Gly170Asn or Gly170Ser) (5). blaGES has been described as gene cassettes associated with class 1 integrons on plasmids with different types of replicons (6). Since the first description of Klebsiella pneumoniae from France in 2000 (7), several human outbreaks of GES-producing Gram-negative bacteria have been described worldwide (8–12). Some GES-type carbapenemases have been found in environmental matrices (13) and clinical isolates, most frequently associated with single occurrences (14).

Despite worldwide reports, GES enzymes are not among the most widespread carbapenemase families (14). In southern Brazil, epidemiological studies conducted by our group have shown a gradual increase in antimicrobial resistance in hospitalized patients in the last 20 years (15–17). However, GES enzymes were not found (18, 19). Although GES enzymes have already been reported in several countries, few studies have explored the genetic context of these ARGs, especially in Brazil. Therefore, we performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and analysis of GES-producing Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. from two hospital effluents to provide genetic information about resistance determinants. These enzymes may be associated with genetic elements that can provide mobility, facilitating their transfer to clinically relevant mobile vectors. Knowledge of the genetic contexts of blaGES will enable a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving mobilization and the emergence of resistance genes in different microorganisms that, through hospital effluents, will reach wastewater treatment plants, the major interfaces between humans and the environment.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial resistance profile of GES type-producing Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp.

In the seven isolates studied (Aeromonas spp., n = 5, and Klebsiella spp., n = 2), we observed a resistance to β-lactams and aminoglycosides, being that Aero28 and KPN47 were multidrug resistant. In addition, Aero28 was resistant to meropenem-vaborbactam and imipenem-relebactam, but not to ceftazidime-avibactam. All phenotypic tests to determine extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and carbapenemases producers converged with the catalytic property of each GES variant. The Aeromonas veronii isolates were inhibited by EDTA due to an intrinsic metallo-β-lactamase (CphA) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility profile of Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. from hospital effluents

| Strain, GES type | MIC (mg/L) of:a |

ESBLe | Carbapenemases |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI | CAZ | CAZ-AVIb | CFDC | CTX | CPM | CIP | CST | ERT | GEN | IMI | IMI-RELc | MER | MER-VABd | POL | TIG | Class A | Class B | ||

| A. caviae Aero19, GES-1 | 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.5 | + | − | − |

| A. caviae Aero21, GES-1 | 32 | 8 | ≤0.015 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | ≤0.015 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − |

| A. caviae Aero52, GES-1 | 8 | 16 | 0.25 | 2 | 4 | 64 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | + | − | − |

| A. veronii Aero22, GES-16 | 32 | >64 | ≤0.015 | 1 | >128 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.5 | >64 | 32 | >128 | 0.25 | 32 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + |

| A. veronii Aero28, GES-7 | >32 | >64 | ≤0.015 | 0.06 | 64 | 16 | 4 | 0.5 | >64 | 64 | >128 | >8 | 64 | >32 | 2 | 1 | + | − | + |

| K. quasipneumoniae KPN47, GES-5 | >32 | >64 | 1 | 0.5 | >128 | 64 | 4 | 0.25 | 64 | >128 | 32 | 2/4 | 32 | 2 | 2 | 8 | + | + | − |

| K. grimontii KOX60, GES-5 | 8 | >64 | 1 | 2 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | 64 | 16 | 16 | 0.25 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | + | + | − |

| E. coli conjugate 21, GES-1 | 32 | >16 | ND | ND | 4 | <4 | 0.5 | 0.25 | <0.25 | 2 | <0.5 | ND | <0.5 | ND | 1 | <1 | + | − | − |

| E. coli transformant 22, GES-16 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.12 | 0.06 | ≤0.06 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1 | ≤0.06 | + | − | − |

| E. coli transformant 28, GES-7 | 2 | >32 | 2 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.25 | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | 0.015 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1 | ≤0.06 | + | − | − |

| E. coli transformant 60, GES-5 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.06 | ≤0.06 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 1 | ≤0.06 | + | − | − |

| E. coli J53 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.015 | 0.25 | ≤0.12 | 0.12 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | 2 | ≤0.06 | − | − | − |

| E. coli TOP10 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.015 | 0.25 | ≤0.12 | 0.12 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | 1 | ≤0.06 | − | − | − |

AMI, amikacin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CAZ-AVI, ceftazidime-avibactam; CFDC, cefiderocol; CTX, cefotaxime; CPM, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CST, colistin; ERT, ertapenem; GEN, gentamicin; IMI, imipenem; IMI-REL, imipenem-relebactam; MER, meropenem; MER-VAB, meropenem-vaborbactam; POL, polymyxin B; TIG, tigecycline; ND, not determined.

The MIC of ceftazidime was measured with a fixed avibactam concentration of 4 mg/L.

The MIC of imipenem was measured with a fixed relebactam concentration of 4 mg/L.

The MICs of meropenem were measured with a fixed vaborbactam concentration of 8 mg/L except for K. grimontii KOX60, which was measured with a fixed vaborbactam concentration of 4 mg/L.

(+), positive phenotypic test; (−), negative phenotypic test.

Furthermore, plasmid DNA from Aero22, Aero28, and KOX60 strains was successfully transferred by electroporation into Escherichia coli TOP10 cells, and conjugation experiments of blaGES-encoding plasmids were successfully performed only for Aeromonas caviae (Aero21); this plasmid harbored all the genes required to autonomously conjugate (GenBank accession no. CP068231). Additionally, repeated attempts to transfer resistance by conjugation or transformation were unsuccessful to Aero19, Aero52, and KPN47. GES-type ESBL transconjugants and transformants showed similar resistance profiles to cephalosporins as those of the donor strains. Moreover, GES-type carbapenemases transformants were susceptible to carbapenems in comparison to the donor strains (Table 1).

Resistome and blaGES-encoding plasmid configurations.

Table 2 summarizes genome information of GES type-producing Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. The sequence analysis of plasmids of three A. caviae isolates carrying blaGES-1 showed that p1Aero19 and p1Aero52, nonmobilizable plasmids, presented tellurite resistance (terB). Conversely, the p1Aero21, a conjugative plasmid, harbored cobalt, zinc, and cobalt-zinc-cadmium resistance gene (czcD) and mercury operon (mer). All of these plasmids were nontypeable.

TABLE 2.

Sequence type, genome characteristics, and blaGES-encoding plasmids of Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. from hospital effluents

| Strain | Genome | Length (bp) | GC% | MLST | Inc group | Integron | Resistance genesa | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. caviae Aero19 | Chromosome | 4,371,624 | 61.6 | 884 | blaMOX-5-like, blaOXA-504-like | CP068232 | ||

| p1 | 110,559 | 58.9 | Nontypeable | In2062 | blaGES-1, dfrA22, arr-6b, qacEΔ1, sul1, terB | CP068233 | ||

| A. caviae Aero21 | Chromosome | 5,123,400 | 60.6 | 885 | blaMOX-1-like, blaOXA-504-like | CP068231 | ||

| p1 | 244,072 | 57.8 | Nontypeable | In2029 | aacA7, blaGES-1, catB3, qacEΔ1, sul1, dfrA22, czcD, mer | CP068231 | ||

| A. caviae Aero52 | Chromosome | 4,386,545 | 61.6 | 884 | blaMOX-5-like, blaOXA-504-like | CP066813 | ||

| p1 | 111,631 | 58.9 | Nontypeable | In2062 | blaGES-1, dfrA22b, arr6b, qacEΔ1, sul1, terB | CP066814 | ||

| A. veronii Aero22 | Chromosome | 5,060,940 | 58.3 | 886 | aphA15, aadA1, blaOXA-1-like, blaOXA-12-like, ampS, cphA3 | JAEMTZ000000000 | ||

| p1 | 80,584 | 56.6 | P6 | In2059 | blaGES-16, qacEΔ1, sul1, dfrA21, aacA4'-8, blaOXA-17, aphA15, blaOXA-4, aadA1, blaTLA-1, tetC, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, mph(E), msr(E) | JAEMTZ010000183.1 | ||

| Aeromonas veronii Aero28 | Chromosome | 4,905,987 | 58.5 | 257 | blaOXA-12-like, ampS, cphA3 | JAEMUA000000000 | ||

| p2 | 9,413 | 54.1 | Q1 | In2061 | blaGES-7, aacA4', qacEΔ1, sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr | JAEMUA010000108 | ||

| K. quasipneumoniae KPN47 | Chromosome | 5,696,094 | 57.5 | 5527 | blaOKP-B4, blaSHV-5, rmtD, fosA6, oqxA, oqxB, ompK36, ompK37, gyrA, acrR | CP066859 | ||

| p1 | 170,976 | 53.5 | M1 | In200 | qacEΔ1, sul1, blaGES-5, dfrA22, blaGES-1Δ2, aacA4'-3, aacA4'-3, blaTEM-1A, blaSHV-5, blaOXA-9, rmtD1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CP066860 | ||

| K. grimontii KOX60 | Chromosome | 6,070,417 | 55.6 | 350 | blaOXY-6-1, oqxB | CP067433 | ||

| p2 | 136,576 | 54.9 | FII-FIA | In174 | blaGES-5, sμL, qacEΔ1 | CP067435 | ||

| p3 | 128,898 | 54.3 | FII | In174 | blaGES-5, sμL, qacEΔ1 | CP067436.1 |

czcD, cobalt-zinc-cadmium resistance gene; mer, mercury operon.

BLASTn analysis showed low similarity (23% coverage and 98.4% identity) among two IncP6 plasmids, p1Aero22 from A. veronii and pKRA-GES-5 from a clinical K. pneumoniae strain (GenBank accession no. MN436715) (20). Only replication initiation and partitioning genes showed similarity. P1Aero22 presented other resistance genes, such as blaTLA-1 and tetC, in a composite transposon, ISKpn15. The other important resistance genes were found in different integrons. The IncQ1 plasmid (p2Aero28) shares high similarity (100% coverage and 99.94% identity) with a plasmid from a clinical Klebsiella variicola isolate (GenBank accession no. CP066873), showing a difference in GES type. Both plasmids had mobilization elements (mob genes).

A conjugative plasmid (p1KPN47) from K. quasipneumoniae (IncM1) showed the BLASTn analysis similarity (86% coverage and 99.99% identity) with a clinical K. pneumoniae isolate (GenBank accession no. KT935445) (21, 22). Similar transfer regions and replication initiation and partitioning genes were found. Both plasmids were identified in isolates from Brazil and characterized as coproducers of carbapenemases and 16S-RMTase, with multiple copies of IS26 and rmtD1-contanining regions duplicated in tandem (Fig. 1F). Among chromosome-related resistant genes, an rmtD copy was also recognized in K. quasipneumoniae (Table 2). Nucleotide insertions in the loop three regions of OmpK36 and OmpK37 were observed by DNA sequencing, and this type of mutation increases carbapenem MICs.

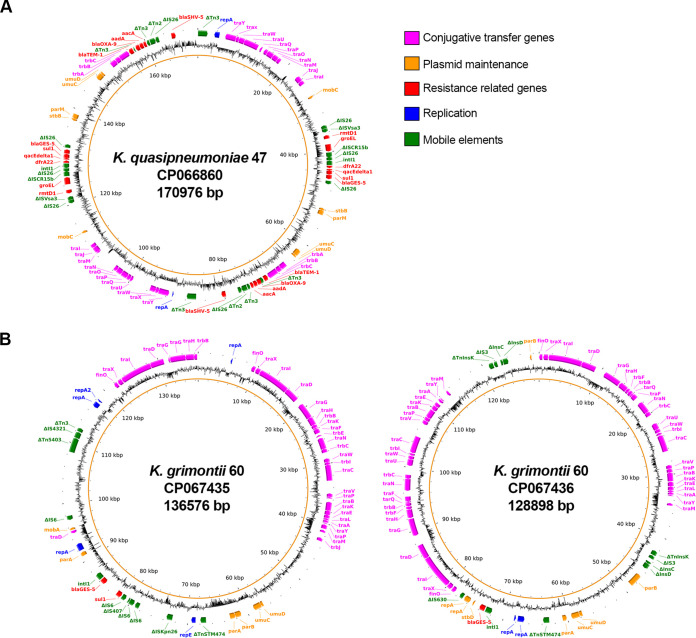

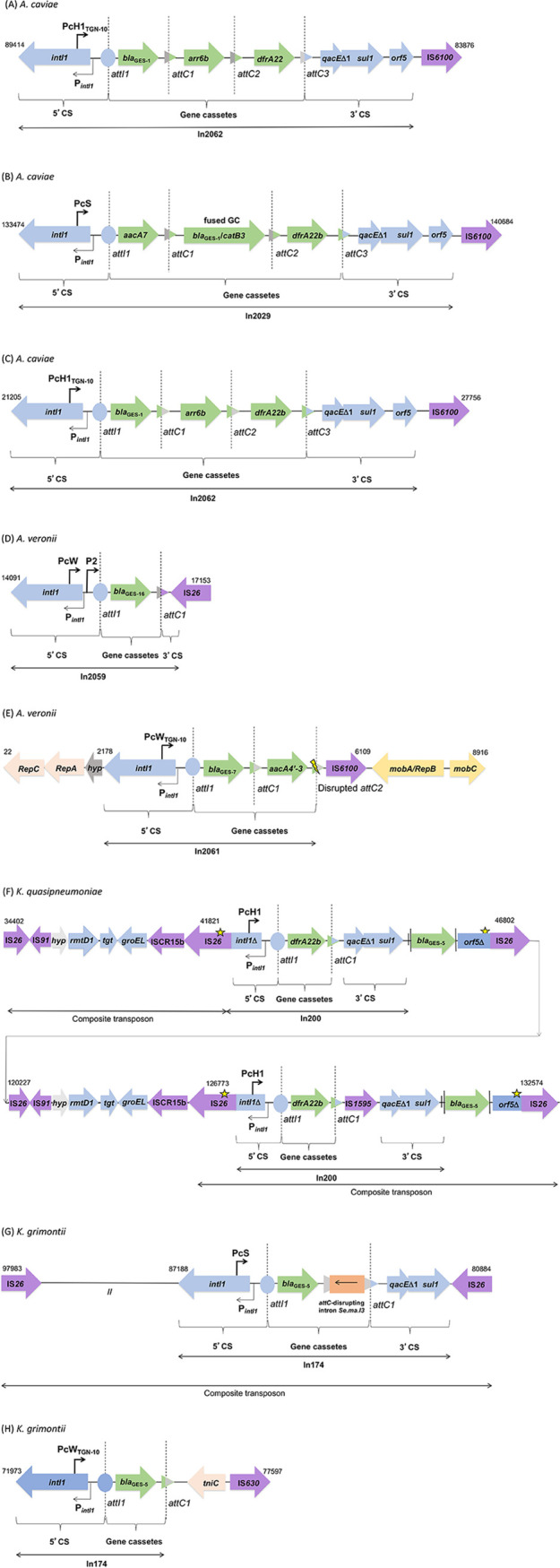

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of regions enclosing class 1 integrons detected among the bacterial population analyzed in the present survey. (A) A. caviae (Aero19) In2062; (B) A. caviae (Aero21) In2029; (C) A. caviae (Aero52) In2062; (D) A. veronii (Aero22) In2059. The 3′ CS in In2059 is truncated by IS26. (E) A. veronii (Aero28) In2061. The yellow ray means the attC is disrupted, and therefore, the gene cassette cannot be mobilized anymore. The 3′ CS is truncated by IS6100. (F) K. quasipneumoniae (KPN47) In200. A star means premature intI1 STOP codon and frameshift in orf5. (G) K. grimontii (p2KOX60), In174; (H) K. grimontii (p3KOX60), In174. Blue, conserved 5′ CS and 3′ CS; green, gene cassettes; purple, insertion sequences; //, 10-kb gap with different genes.

K. grimontii carried two conjugative distinct plasmids carrying blaGES-5 (p2KOX60 and p3KOX60) (Fig. 2). The p2KOX60 harbored multiple replicons (FII-FIA) and displayed similarity (80% coverage and 99.99% identity) with a plasmid from wastewater K. grimontii strain (GenBank accession no. CP055312). The p3KOX60 carried an FII replicon and exhibited similarity (74% coverage and 99.14% identity) with a plasmid from freshwater Klebsiella michiganensis strain (GenBank accession no. CP058121). The main difference between these plasmids was the presence of integrons carrying blaGES.

FIG 2.

Map of the plasmids carrying blaGES-5 from KPN47 and KOX60 recovery at CHC/UFPR effluents. (A) The representative genes of the K. quasipneumoniae from the CP066860 plasmid are shown in colored boxes. (B) The representative genes of the K. grimontii from the CP067435 plasmid and CP067436 plasmid are shown in colored boxes.

By PFGE-S1 experiment and hybrid assembly, we found a unique plasmid in Aero19 (110 kb) and Aero21 (244 kb), 2 plasmids in Aero28 (9 and 59 kb), 3 plasmids in Aero22 (5.8, 23.9, and 80.5 kb) and Aero52 (9.7, 24.1, and 111.6 kb), 8 plasmids in KOX60 (ranging from 48 to 179.9 kb), and 10 plasmids in KPN47 (ranging from 10.2 to 170.9 kb).

Novel class 1 integrons carrying blaGES in Aeromonas spp.

The hybrid assembly analysis revealed that blaGES from Aeromonas spp. was located in novel functional class 1 integrons (Fig. 1). Integrons with new and completely sequenced gene cassette arrays were considered for the attribution of new In numbers (23).

The In2062 (Fig. 1A and C) from A. caviae (Aero19 and Aero52) contained a blaGES-1-arr6b-dfrA22 gene cassette array. Both integrons harbored the PcH1TGN-10 promoter variant (3, 23). In2029 (Fig. 1B) from A. caviae (Aero21) presented three gene cassettes, aacA7-blaGES-1 and catB3-dfrA22. The blaGES-1 and catB3 cassettes were fused. This integron contained the strongest PcS variant. Both integrons carried a 5′ conserved segment (5′ CS) and 3′ conserved segment (3′ CS), followed by an IS6100.

In2059 (Fig. 1D) from A. veronii (Aero22) consisted of a weak variant (PcW) combined with a second promoter (P2), and the variable region comprised one gene cassette, blaGES-16, and a 3′ CS truncated by IS26. In2061 (Fig. 1E) was identified in A. veronii (Aero28) containing blaGES-7-aacA4′-3 gene cassettes and presented the strong PcWTGN-10 variant (3, 23). The attC of aacA4′-3 is disrupted, and, therefore, the gene cassette cannot be mobilized anymore. The 3′ CS region was absent, and IS6100 was adjacent to the gene cassette.

Genetic plasticity in known class 1 integrons carrying blaGES-5 in Klebsiella spp.

The plasmid of K. quasipneumoniae (KPN47) displayed two copies of the In200 class 1 integron (GenBank accession no. AJ968952) and presented dfrA22b as gene cassettes, both with a PcH1promoter variant (3, 23). The blaGES-5 gene, usually located as an integron gene cassette, was found between the 3′ CS and orf5Δ but was not associated with any attC and, therefore, not embedded as a mobilizable integron gene cassette. We observed the presence of an IS1595 truncating the gene cassette, which may have caused the displacement of blaGES-5. The first 113 bp of the 5′ CS were deleted due to IS26 insertion (IS26/Δ5′ CS); the 3′ CS included a truncated orf5Δ and an IS26 (Fig. 1F).

K. grimontii (KOX60) exhibited two previously reported class 1 integrons, usually referred to as In174 (GenBank accession no. EU266532), containing one gene cassette (blaGES-5) in two different plasmids. In174 from p2KOX60 presented a strong promoter PcS and a novel group IIc intron that displayed 77% nucleotide identity with Se.ma.I3 (GenBank accession no. AY884051) disrupting attC upstream of the 3′ CS region. This integron was bounded by two copies of IS26, forming a composite transposon (Fig. 1G). The second integron from p3KOX60 presented the strong PcWTGN-10 promoter variant and terminated in a tniC instead of a 3′ CS (Fig. 1H).

Phylogenetic characteristic.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) based on the genomic data assigned six isolates to different STs, A. caviae (Aero19 and Aero52) ST884, A. caviae (Aero21) ST885, A. veronii (Aero22) ST886 (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/aeromonas-spp), K. quasipneumoniae (KPN47) ST5527 (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/), and K. grimontii (KOX6060) ST350 (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/klebsiella-oxytoca). The isolate A. veronii (Aero28) belongs to ST257 identified in China in 2013 (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/aeromonas-spp) (Table 2). KPN47 and KOX60 isolates, initially identified as K. pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (18), were redefined based on whole-genome sequencing as K. quasipneumoniae and K. grimontii, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study reports different GES-type enzymes from hospital effluents. The epidemiology of GES producers is not completely known, and its prevalence or transmission seems to be underestimated. However, there are some reports of environmental bacteria such as Aeromonas spp. (19, 24, 25). Our findings showed great potential of the environment in promoting genetic variability, a fact observed by the presence of novel integrons and the plasticity among the plasmids found. These scenarios are more common in natural environments than clinical settings, suggesting a general role in bacterial adaptation (26).

Antimicrobial resistance genomic analysis revealed that Aeromonas veronii isolates possess chromosomally encoded genes, including blacphA3. As a resultant, this led to increased resistance to carbapenems. The Aero28 isolate presented also showed resistance to the novel carbapenem-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, suggesting that, unlike in Aero22, an induction of the cphA gene may have occurred (27). The absence of this gene led to the reduction of MIC to carbapenems observed in GES-7 and GES-16 transformants. In addition, the MIC of ceftazidime in the GES-16 transformant dramatically declined. Some studies showed that the substitution of Gly170Ser in GES-carbapenemase reduces the hydrolytic efficiency against ceftazidime (28–31).

In Brazil, the presence of blaGES-16 was first reported in two carbapenem-resistant Serratia marcescens clinical isolates in Rio de Janeiro and did not show any relationship with the integron found in our study (28). We identified a novel mobilizable IncP6 plasmid carrying a novel integron that, compared to pKRA-GES-5 (20), had additional acquired resistance genes like tetC, mphE, msrE, and blaTLA-1 and a large number of mobile elements such as ISs, composite transposon, and different integrons. This plasmid group was reported in several species from clinical and wastewater sources, suggesting that they have a vast range of hosts and are associated with bacteria that can persist in the environment for long periods (32).

Genomic analysis of Aero28 showed that the integron (In2061) carrying blaGES-7 belongs to a novel IncQ1 plasmid, which is capable of replication in a very broad range of hosts and is readily mobilizable (33). The comparative BLAST analysis showed that this plasmid was homologous to another plasmid from a K. variicola clinical isolate harboring blaGES-5, deposited by our group in the GenBank database. These plasmids did not show significant homology with the other published IncQ-type plasmids carrying blaGES that are inserted in different mobile elements, two from clinical origin (34, 35) and one from river water (36). Therefore, these findings highlight the spread of the IncQ1 plasmid between different species and environments.

The two isolates of Klebsiella spp. showed resistance to carbapenems and, as observed in GES-16, the β-lactam and aminoglycoside resistance decreased in the GES-5 transformant. Other mechanisms, such as porin loss in KOX60 or modifications in porins such as OmpK36 and OmpK37 in KPN47, are critical for expression of high-level resistance to carbapenems (17).

Members of the genus Klebsiella are known to have stronger associations between ISs and ARGs. Persistent exposure to antibiotics has likely enhanced this association of ISs with ARGs in their genomes (37). In the K. quasipneumoniae isolate (KPN47), a high frequency of IS26 was noted. Furthermore, the ability of IS26 transposase (Tnp26) to function in replicative mode formed two identical large regions of DNA sequences carrying blaGES-5 within class 1 integrons and arrays of important ARGs (2). This plasmid contains a wide range of transposable elements, an important evolutionary feature allowing for frequent genetic transposition leading to a plasmid fusion and, presumably, a better adaptation of the plasmid to the bacterial host (38). A similar situation involving blaGES-5 was recently reported in C. freundii isolated from a hospital wastewater treatment plant in Taiwan (39), drawing attention to hospital effluents.

Another interesting insight in K. quasipneumoniae isolate refers to identifying 16S rRNA-methyltransferase (rmtD1) in both plasmid and chromosome, showing a high resistance level against all aminoglycosides. It is noteworthy that most genes encoding 16S RMTases are typically located on plasmids that also encode ESBLs and carbapenemases determinants (40). Comparing the genetic environment of rmtD1 with pKp64/11, we observed, in both plasmids, an rmtD1-containing region flanked by IS26, forming composite transposons. IS26 may have played a role in the mobilization of rmtD1 between different species (22, 41). Consequently, the duplication of IS26-flanked structures in a tandem array formation has been observed in the presence of selective pressure from the corresponding antimicrobial agents (22).

The duplicity of blaGES-5 was also observed in K. grimontii (KOX60), presented as gene cassettes in class 1 integrons in two distinct plasmids, as recently reported in a P. aeruginosa clinical isolate harboring two plasmids carrying blaIMP (42). One integron (In174, p2KOX60) was located in a composite transposon (IS26), and the second (In174, p3KOX60), despite having the same gene cassette array, presented a different promoter variant and was not flanked by IS26, showing that these integrons are unrelated (39). Carbapenem-resistant K. grimontii (KPC-2) has been reported once, recovered from clinical samples in China (43), but K. grimontii carrying blaGES-5 recovered from hospital effluent in the first report.

By analyzing the complete sequence of the two IncF plasmids, we note the presence of multireplication proteins in p2KOX60 (repA and repE), featuring a replicon-type IncFII-FIA, whereas p3KOX60 had only repA. The presence of multiple replicons can allow those that are not driving replication to diverge, potentially changing incompatibility (44). These replication proteins, partitioning genes, and tra genes were responsible for the similarity of our plasmids to others recovered from the water environment in the United Kingdom. Our plasmids differ mainly by the acquisition of carbapenem resistance genes.

Although several Pc variants with different strengths were found in our isolates, including a Pc promoter combined with a second P2 promoter (Aero22), we were unable to observe a significant change in the MICs of the transconjugants. Notably, in the context of greater antibiotic selective pressure, the need to express gene cassettes more efficiently may lead to the selection of more efficient Pc sequences (3, 45). Further experimental studies covering the relative strengths of these Pc variant promoters should be performed.

Among all isolates, we achieved a transconjugant only for A. caviae (Aero21). Based on sequence analysis, p1Aero21 exhibits machinery needed for conjugation, all tra genes, and the type IV secretion system (T4SS). Genes transfer by conjugation is known to contribute to the genetic dynamics of bacterial populations living in a variety of environments (46). In the K. grimontii plasmid, we observed the presence of fertility inhibition protein (FinO) that may have decreased conjugation efficiency (2, 47). Further, in the K. quasipneumoniae plasmid, despite the presence of a tra region that included genes essential for F transfer, the conjugation was unsuccessful.

In summary, our study reports different blaGES in novel plasmids within novel class 1 integrons and different STs of Aeromonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. recovered from hospital effluents, reflecting what could be found within the patient’s gut. We share an in-depth exploration of understanding the molecular evolutionary mechanisms of blaGES mobilome, along with their potential dynamic transmission and plasmid plasticity.

The presence of novel mobilizable or conjugative plasmids under different contexts, including an impressive mesh of interactions with transposable elements, resulting in plasmid fusion and acquisition of multireplicons, can translate into a problem of large proportion. This is because wastewater treatment plants cannot eliminate these MGEs and antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) that can persist in river water and thus constitute a threat of dissemination in the environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study settings and ethics statement.

The Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Complexo Hospital de Clínicas, Universidade Federal do Paraná (CHC/UFPR), approved this study under the reference number CAAE 11087012.0.0000.0096.

Characterization of bacterial isolates and antimicrobial resistance.

We selected a group of seven GES type-producing isolates from hospital effluents, as identified in previous studies (18, 19). Wastewater samples were collected at the CHC/UFPR, a 640-bed academic care hospital, and Hospital Pequeno Principe (HPP), a 390-bed pediatric academic care hospital. The hospitals are located in Curitiba, Paraná, southern Brazil. These isolates were identified using the Vitek 2 compact system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and mass spectrometry (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry [MALDI-TOF MS]) using microflex LT Biotyper 3.0 (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and Vitek MS (bioMérieux) instruments. All isolates were stored in 15% glycerol-containing tryptic soy broth and frozen at −80°C until further use.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by agar or broth dilution as recommended by CLSI (48, 49). The tests were interpreted according to CLSI standards (49, 50). Double-disk synergy was assessed to detect ESBL (51) and class A and B carbapenemases (52).

Plasmid profile and translocation of blaGES.

Total plasmid DNA extraction of Klebsiella species and Aeromonas species isolates harboring blaGES was performed using the GenElute plasmid midiprep kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To define the size and number of plasmids in each isolate, S1 nuclease pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE-S1) was performed as described by Kaufmann (53). Conjugation experiments were performed using Aeromonas and Klebsiella isolates as donors and azide-resistant E. coli J53 as receptor strain. Transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar containing 150 mg/L sodium azide and 50 mg/L ampicilin. Additionally, DNA plasmids obtained from the extraction by NucleoBond Xtra Plus midikit (Macherey-Nagel, Duren, Germany) were transformed by electroporation into E. coli TOP10. Electroporation conditions were 100 Ω, 13 kV/cm, and 25 μF (54), and transformants were selected with ceftazidime (0.5 mg/L).

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the GenElute bacterial genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified using the Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) high-sensitivity (HS) assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA). Illumina sequencing libraries with an average insert size of 600-bp fragments were generated using an Illumina Nextera XT DNA library kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Libraries were quantified, and their quality was verified using a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Whole-genome sequencing of paired-end libraries (PE; 2 × 250 bp) was performed using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc.). In addition, long-read WGS was performed using a MinION sequencer (Nanopore, Oxford, UK). MinION sample preparation was carried out using the rapid barcoding kit SQK-RBK-004 and the flow cell priming kit EXP-FLP002 (Oxford Nanopore), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Raw read quality was checked using FastQC version 0.11.15 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), and quality-based trimming and filtering were performed using Trimmomatic version 0.35 (55). SPAdes version 3.12.0 (56) was used to combine MinIon and Illumina data to produce a hybrid assembly of chromosomes and plasmids. The number of contigs was more contiguous than the assembly using Illumina data alone, with SPAdes producing a single chromosomal contig. Completeness and taxonomic classification of the assemblies were verified using the DFAST tool (https://dfast.nig.ac.jp/dqc/submit/; accessed in September 2020). Chromosomal and plasmid sequences were annotated using Prokka version 1.12 (57). Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) version 1.073 (58) and Artemis version 18.0.0 (59) were applied to predict coding sequences (CDSs). We searched all the plasmids of the GenBank database (accessed in May 2022) using BLASTn (60). Comparative plasmid maps of blaGES-5 were generated from the assembled contigs using BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG) version 0.95 (61).

Profiling of mobile genetic elements and antimicrobial resistance genes.

Chromosomal and plasmid resistome were predicted using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) version 3.1.2 (https://card.mcmaster.ca/, accessed January 2020) and ResFinder database version 4.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/, accessed December 2020).

Plasmid replicon types in the assemblies were determined using the PlasmidFinder tool 2.0.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/, accessed December 2020). Moreover, the allele types of IncF plasmids were assigned using IncF replicon typing pMLST, available at the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/pMLST/, accessed December 2020). Chromosomal and plasmid transposons were identified using Mobile Element Finder 1.0.3 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MobileElementFinder/, accessed December 2020) and ISfinder (https://isfinder.biotoul.fr/index.php, accessed January 2021). Plasmid integrons, integrases, and gene cassettes were predicted using the INTEGRALL database version 1.2 (http://integrall.bio.ua.pt/, accessed June 2021).

Molecular typing.

Sequences of housekeeping genes of unknown STs were curated at the K. pneumoniae MLST database at the Pasteur Institute (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/), the K. grimontii MLST website (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/klebsiella-oxytoca), and the Aeromonas spp. MLST website (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/aeromonas-spp).

Data availability.

Genomic assemblies of chromosomes and plasmids of the seven isolates were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers CP068232 and CP068233 (Aeromonas caviae 19), CP068231 (Aeromonas caviae 21), JAEMTZ000000000 (Aeromonas veronii 22), JAEMUA000000000 (Aeromonas veronii 28), CP066813 to CP066816 (Aeromonas caviae 52), CP066859 to CP066869 (Klebsiella quasipneumoniae 47), and CP067433 to CP067441 (Klebsiella grimontii KOX 60).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Institut Pasteur teams for the curation and maintenance of BIGSdb-Pasteur databases at http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/. We thank JMI Laboratories for performing the susceptibility testing for cefiderocol, meropenem-vaborbactam, imipenem-relebactam, and ceftazidime-avibactam.

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior-Brazil (CAPES), financing code 001. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

D.C., J.K.P., and L.M.D.-C. developed the concept and methodology; D.C., C.P.Z., and T.C.M.S. performed the experiments; D.C., D.M., and T.J. analyzed the data and made the figures; D.C. wrote the original manuscript; J.K.P. and L.M.D.-C. supervised the study; and D.C., J.K.P., and L.M.D.-C. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Danieli Conte, Email: conte.danieli@gmail.com.

Libera Maria Dalla-Costa, Email: lmdallacosta@gmail.com.

Daria Van Tyne, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.von Wintersdorff CJH, Penders J, van Niekerk JM, Mills ND, Majumder S, van Alphen LB, Savelkoul PHM, Wolffs PFG. 2016. Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Front Microbiol 7:173. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partridge SR, Kwong SM, Firth N, Jensen SO. 2018. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 31:e00088-17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00088-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jové T, Da Re S, Denis F, Mazel D, Ploy M-C. 2010. Inverse correlation between promoter strength and excision activity in class 1 integrons. PLoS Genet 6:e1000793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walther-Rasmussen J, Høiby N. 2007. Class A carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:470–482. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naas T, Oueslati S, Bonnin RA, Dabos ML, Zavala A, Dortet L, Retailleau P, Iorga BI. 2017. Beta-lactamase database (BLDB)–structure and function. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 32:917–919. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2017.1344235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Queenan AM, Bush K. 2007. Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poirel L, Le Thomas I, Naas T, Karim A, Nordmann P. 2000. Biochemical sequence analyses of GES-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and the class 1 integron In52 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:622–632. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.3.622-632.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong SH, Bae IK, Kim D, Hong SG, Song JS, Lee JH, Lee SH. 2005. First outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates producing GES-5 and SHV-12 extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4809–4810. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4809-4810.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poirel L, Weldhagen GF, De Champs C, Nordmann P. 2002. A nosocomial outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates expressing the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase GES-2 in South Africa. J Antimicrob Chemother 49:561–565. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duarte A, Boavida F, Grosso F, Correia M, Lito LM, Cristino JM, Salgado MJ. 2003. Outbreak of GES-1 β-lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a university hospital in Lisbon, Portugal. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1481–1482. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1481-1482.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picão RC, Poirel L, Gales AC, Nordmann P. 2009. Diversity of β-lactamases produced by ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates causing bloodstream infections in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3908–3913. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00453-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries JJC, Baas WH, van der Ploeg K, Heesink A, Degener JE, Arends JP. 2006. Outbreak of Serratia marcescens colonization and infection traced to a healthcare worker with long-term carriage on the hands. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 27:1153–1158. doi: 10.1086/508818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherak Z, Loucif L, Moussi A, Rolain J. 2021. Carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in aquatic environments: a review. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 25:287–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellington MJ, Davies F, Jauneikaite E, Hopkins KL, Turton JF, Adams G, Pavlu J, Innes AJ, Eades C, Brannigan ET, Findlay J, White L, Bolt F, Kadhani T, Chow Y, Patel B, Mookerjee S, Otter JA, Sriskandan S, Woodford N, Holmes A. 2020. A multispecies cluster of GES-5 carbapenemase–producing Enterobacterales linked by a geographically disseminated plasmid. Clin Infect Dis 71:2553–2560. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almeida S.d, Nogueira K da S, Palmeiro JK, Scheffer MC, Stier CJN, França JCB, Costa LMD. 2014. Nosocomial meningitis caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae producing carbapenemase, with initial cerebrospinal fluid minimal inflammatory response. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 72:398–399. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20140030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nogueira K da S, Conte D, Maia FV, Dalla-Costa LM. 2015. Distribution of extended-spectrum β -lactamase types in a Brazilian tertiary hospital. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 48:162–169. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0009-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmeiro JK, de Souza RF, Schörner MA, Passarelli-Araujo H, Grazziotin AL, Vidal NM, Venancio TM, Dalla-Costa LM. 2019. Molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in a Brazilian tertiary hospital. Front Microbiol 10:1669. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conte D, Palmeiro JK, da Silva Nogueira K, de Lima TMR, Cardoso MA, Pontarolo R, Degaut Pontes FL, Dalla-Costa LM. 2017. Characterization of CTX-M enzymes, quinolone resistance determinants, and antimicrobial residues from hospital sewage, wastewater treatment plant, and river water. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 136:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conte D, Palmeiro JK, Bavaroski AA, Rodrigues LS, Cardozo D, Tomaz AP, Camargo JO, Dalla-Costa LM. 2021. Antimicrobial resistance in Aeromonas species isolated from aquatic environments in Brazil. J Appl Microbiol 131:169–181. doi: 10.1111/jam.14965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Literacka E, Izdebski R, Urbanowicz P, Żabicka D, Klepacka J, Sowa-Sierant I, Żak I, Garus-Jakubowska A, Hryniewicz W, Gniadkowski M. 2020. Spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST45 producing GES-5 carbapenemase or GES-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in newborns and infants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:6–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00595-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bueno MFC, Francisco GR, O'Hara JA, de Oliveira Garcia D, Doi Y. 2013. Coproduction of 16S rRNA methyltransferase RmtD or RmtG with KPC-2 and CTX-M group extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2397–2400. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02108-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bueno MFC, Francisco GR, de Oliveira Garcia D, Doi Y. 2016. Complete sequences of multidrug resistance plasmids bearing rmtD1 and rmtD2 16S rRNA methyltransferase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1928–1931. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02562-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moura A, Soares M, Pereira C, Leitao N, Henriques I, Correia A. 2009. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics 25:1096–1098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girlich D, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2011. Diversity of clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum-β-lactamases in Aeromonas spp. from the Seine River, Paris, France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1256–1261. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00921-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montezzi LF, Campana EH, Corrêa LL, Justo LH, Paschoal RP, da Silva ILVD, Souza MDCM, Drolshagen M, Picão RC. 2015. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing bacteria in coastal recreational waters. Int J Antimicrob Agents 45:174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moura A, Jové T, Ploy M-C, Henriques I, Correia A. 2012. Diversity of gene cassette promoters in class 1 integrons from wastewater environments. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:5413–5416. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00042-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hilt EE, Fitzwater SP, Ward K, de St Maurice A, Chandrasekaran S, Garner OB, Yang S. 2020. Carbapenem resistant Aeromonas hydrophila carrying blacphA7 isolated from two solid organ transplant patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:563482. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.563482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streling AP, Barbosa PP, Marcondes MF, Nicoletti AG, Picão RC, Pinto EC, Marques EA, Oliveira V, Gales AC. 2018. Genetic and biochemical characterization of GES-16, a new GES-type β-lactamase with carbapenemase activity in Serratia marcescens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 92:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae IK, Lee Y-N, Jeong SH, Hong SG, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim HJ, Youn H. 2007. Genetic and biochemical characterization of GES-5, an extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 58:465–468. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogaerts P, Naas T, El Garch F, Cuzon G, Deplano A, Delaire T, Huang T-D, Lissoir B, Nordmann P, Glupczynski Y. 2010. GES extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Belgium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4872–4878. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00871-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kotsakis SD, Papagiannitsis CC, Tzelepi E, Legakis NJ, Miriagou V, Tzouvelekis LS. 2010. GES-13, a β-lactamase variant possessing Lys-104 and Asn-170 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1331–1333. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01561-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu X, Yu X, Shang Y, Xu H, Guo L, Liang Y, Kang Y, Song L, Sun J, Yue F, Mao Y, Zheng B. 2019. Emergence and characterization of a novel IncP-6 plasmid harboring blaKPC–2 and qnrS2 genes in Aeromonas taiwanensis isolates. Front Microbiol 10:2132. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loftie-Eaton W, Rawlings DE. 2012. Diversity, biology and evolution of IncQ-family plasmids. Plasmid 67:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poirel L, Carrer A, Pitout JD, Nordmann P. 2009. Integron mobilization unit as a source of mobility of antibiotic resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2492–2498. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00033-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poirel L, Carattoli A, Bernabeu S, Bruderer T, Frei R, Nordmann P. 2010. A novel IncQ plasmid type harbouring a class 3 integron from Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1594–1598. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teixeira P, Tacão M, Pureza L, Gonçalves J, Silva A, Cruz-Schneider MP, Henriques I. 2020. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a Portuguese river: blaNDM, blaKPC and blaGES among the detected genes. Environ Pollut 260:113913. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.113913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razavi M, Kristiansson E, Flach C-F, Larsson DGJ. 2020. The association between insertion sequences and antibiotic resistance genes. mSphere 5:e00418-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00418-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X, Dong N, Chan EWC, Zhang R, Chen S. 2021. Carbapenem resistance-encoding and virulence-encoding conjugative plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Trends Microbiol 29:65–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomi R, Matsuda T, Yamamoto M, Tanaka M, Jové T, Chou P-H, Matsumura Y. 2021. Occurrence of class 1 integrons carrying two copies of the blaGES-5 gene in carbapenem-non-susceptible Citrobacter freundii and Raoultella ornithinolytica isolated from wastewater. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 26:230–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bail L, Ito CAS, Arend LNVS, Pilonetto M, Nogueira K da S, Tuon FF. 2021. Distribution of genes encoding 16S rRNA methyltransferase in plazomicin-nonsusceptible carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in Brazil. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 99:115239. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wachino J-i, Yamane K, Shibayama K, Kurokawa H, Shibata N, Suzuki S, Doi Y, Kimura K, Ike Y, Arakawa Y. 2006. Novel plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA methylase, RmtC, found in a Proteus mirabilis isolate demonstrating extraordinary high-level resistance against various aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:178–184. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.178-184.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.López-García A, Rocha-Gracia RDC, Bello-López E, Juárez-Zelocualtecalt C, Sáenz Y, Castañeda-Lucio M, López-Pliego L, González-Vázquez MC, Torres C, Ayala-Nuñez T, Jiménez-Flores G, de la Paz Arenas-Hernández MM, Lozano-Zarain P. 2018. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa carrying IMP variants recovered from a Mexican hospital. Infect Drug Resist 11:1523–1536. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S173455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu L, Feng Y, Hu Y, Kang M, Xie Y, Zong Z. 2018. Klebsiella grimontii, a new species acquired carbapenem resistance. Front Microbiol 9:2170. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villa L, García-Fernández A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. 2010. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:2518–2529. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghaly TM, Chow L, Asher AJ, Waldron LS, Gillings MR. 2017. Evolution of class 1 integrons: mobilization and dispersal via food-borne bacteria. PLoS One 12:e0179169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davison J. 1999. Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment. Plasmid 42:73–91. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mark Glover JN, Chaulk SG, Edwards RA, Arthur D, Lu J, Frost LS. 2015. The FinO family of bacterial RNA chaperones. Plasmid 78:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hackel MA, Tsuji M, Yamano Y, Echols R, Karlowsky JA, Sahm DF. 2019. Reproducibility of broth microdilution MICs for the novel siderophore cephalosporin, cefiderocol, determined using iron-depleted cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 94:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2022. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 32nd ed. CLSI M100-ED32. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2016. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria, 3rd ed. CLSI guideline M45. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jarlier V, Nicolas MH, Fournier G, Philippon A. 1988. Extended broad-spectrum β-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer β-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis 10:867–878. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.4.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsakris A, Poulou A, Pournaras S, Voulgari E, Vrioni G, Themeli-Digalaki K, Petropoulou D, Sofianou D. 2010. A simple phenotypic method for the differentiation of metallo-β-lactamases and class A KPC carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1664–1671. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaufmann ME. 1998. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, p 33–50. In Woodford N, Johnson AP (ed), Molecular bacteriology, vol 15. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheng Y, Mancino V, Birren B. 1995. Transformation of Escherichia coli with large DNA molecules by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res 23:1990–1996. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.11.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best A, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, Barrell B. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alikhan N-F, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. 2011. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Genomic assemblies of chromosomes and plasmids of the seven isolates were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers CP068232 and CP068233 (Aeromonas caviae 19), CP068231 (Aeromonas caviae 21), JAEMTZ000000000 (Aeromonas veronii 22), JAEMUA000000000 (Aeromonas veronii 28), CP066813 to CP066816 (Aeromonas caviae 52), CP066859 to CP066869 (Klebsiella quasipneumoniae 47), and CP067433 to CP067441 (Klebsiella grimontii KOX 60).