Abstract

Accurate assessment of adverse health effects attributable to ingestion of inorganic arsenic (As) present in contaminated soils requires determination of the internal dose of metal provided by ingested soil. This calculation requires estimation of the oral bioavailability of soil-borne (As). Animal models to assess the bioavailability of soil (As) are frequently used as surrogates for determination of this variable in humans. A mouse assay has been widely applied to estimate the bioavailability of As in soils at sites impacted by mining, smelting, and pesticides. In the mouse assay, the relative bioavailability (RBA) of soil (As) is determined as the ratio of the fraction of the ingested arsenic dose excreted in urine after consumption of diets containing a test soil or the soluble reference compound, sodium arsenate. The aim of the current study was to compare (As) bioavailability measured in the mouse assay with reported estimates in humans. Here, a pharmacokinetic model based on excretion of arsenic in urine and feces was used to estimate the absolute bioavailability (ABA) of As in mice that received an oral dose of sodium arsenate. Based upon this analysis, in mice that consumed diet amended with sodium arsenate, the ABA was 85%. This estimate of arsenic ABA for the mouse is comparable to estimates in humans who consumed (As) in drinking water and diet, and to estimates of ABA in monkeys and swine exposed to sodium arsenate. The concordance of estimates for ABA in mice and humans provides further support for use of the mouse model in human health risk assessment. Sodium arsenate ABA also provides a basis for estimating soil arsenic ABA from RBA estimates obtained in the mouse model.

Keywords: Arsenic, bioavailability, human, mouse, pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Inorganic arsenic (As) is a class 1 carcinogen in humans (IARC 2012). Chronic exposure to inorganic As through use of contaminated water supplies has been associated with an increased cancer risk and other adverse health outcomes (ATSDR 2007, 2016; U.S. EPA 2021; WHO 2011). Surface soils are also potential sources of exposure to this metalloid. This exposure may occur through direct ingestion of As-contaminated soils or by transfer of As from soil to plants during cultivation (Rehman et al. 2021). Soil As may be geogenic or anthropogenic in origin. Important anthropogenic sources include pesticide production, application of As-containing pesticides, and mining and processing of As-containing ores (ATSDR 2007, 2016; Hughes et al. 2011).

In human health risk assessments, cancer risk associated with ingestion of inorganic As has been estimated by using a cancer slope factor that was derived from epidemiological studies of populations exposed to As in drinking water (U.S. EPA 2021). However, because oral bioavailability of inorganic As in soil tends to be less than that of water-soluble arsenate (U.S. EPA, 2012), this approach may be inadequate for evaluating the cancer risk associated with exposure to inorganic As in soil. Accounting for the lower oral bioavailability of soil-borne inorganic As should improve the predictive value of the cancer risks based upon the cancer slope factor (Bradham et al. 2018b; U.S. EPA 2012, 2020). Notably, many factors might affect the oral bioavailability of inorganic As in soil, including its chemical forms, particle size, and physical and chemical properties of As-bearing soil particles (Davis et al. 1996; Odezulu et al. 2022). Because soil properties that affect soil inorganic As bioavailability vary, site-specific determination of oral bioavailability of soil inorganic As is needed for accurate assessment of cancer risk from exposure to soils at specific sites.

The need for site-specific estimates of oral bioavailability of soil As for humans has stimulated development of animal models to measure relative bioavailability (RBA) of inorganic As (Bradham et al. 2011; Brattin and Casteel 2013; Freeman et al. 1993, 1995; Juhasz et al. 2007; Li et al. 2016, 2021; Roberts et al. 2007). In addition to providing estimates of RBA, animal models continue to be essential for developing and refining in vitro bioaccessibility (IVBA) assays that provide less inexpensive approaches to predicting soil arsenic RBA (Bradham et al. 2018b). The general formula for calculation of RBA of As in a test material (e.g., soil) is the ratio of the absolute bioavailability (ABA) of the As in the test material (TM) and the ABA of As in a reference material (RM; Equation 1):

| (1) |

where ABA is the fraction of the As dose that is absorbed. In many animal models employed to estimate soil As RBA, the reference material is sodium arsenate, a highly water-soluble form of inorganic As.

Several technical aspects of the measurement of ABA make it preferable to use RBA, rather than ABA, as a measure of the bioavailability of soil inorganic As. The standard procedure for estimating ABA of a soluble test material is to compare time-dependent patterns (e.g., area under the curve, AUC) for the concentration of the test material in blood or urine after both oral ingestion and intravenous (iv) dosing. However, for insoluble and complex test materials such as soil, iv administration is not a feasible dosing route. An alternative to the AUC method for measuring the ABA of As in the test and reference materials is to calculate the RBA as the ratio of the urinary excretion fractions (UEF) resulting from oral dosing with test or reference materials (Equation 2):

| (2) |

In Equation 2, UEF is the fraction of the administered dose excreted in urine, ABA is the fraction of the dose absorbed, and fur is the fraction of the absorbed dose excreted in urine. From Equation 2, the ABA of a test or reference material can be determined from a measurement of UEF if the value for fur is known. The value of fur cannot be determined solely from measurements of UEF and requires a more extensive pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of the fate of the administered As dose. However, even if the value for fur is unknown, the ratio UEFs will equal the ratio of ABAs, as long as fur,TM and fur,RM have the same values. Although the equivalence of fur,TM and fur,RM is typically assumed in animal As RBA models, it has not been rigorously evaluated (Bradham et al. 2018b). The aim of the present study was to conduct a PK analysis of data collected from more than 50 mouse assays to estimate the ABA for sodium arsenate in the mouse RBA bioassay.

Materials and methods

Mouse RBA assay

The mouse assay used to estimate the RBA of inorganic As in soil has been described previously (Bradham et al. 2011). Mice used in these assays were 4–6 week-old female C57BL/6 mice weighing 16–20 g (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC). For the studies reported here, test diets were prepared by addition of sodium arsenate heptahydrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or the SRM 2710a Montana soil (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD) to powdered AIN-93 G rodent diet. Notably, SRM 2710a has been routinely used as a quality control standard for mouse RBA assays (Bradham et al. 2018a, 2020). The AIN-93 G rodent diet was prepared from a few processed ingredients (sugar, starch, vegetable oil, casein, vitamin, and mineral mixes) and met the nutritional requirements of mice during periods of rapid growth and during pregnancy and lactation (Reeves, Nielsen, and Fahey 1993). Further, because this diet contains a low concentration of speciated arsenicals (approximately 13 µg/kg of which about 80% is inorganic As), it is an ideal medium for the preparation of test diets (Murko et al. 2018).

Mice were housed in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility and animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. Before the assay, group-housed animals were acclimated in plastic box cages with cellulose bedding, with a 12 h light:dark photoperiod, room temperature 20–22°C, and free access to AIN-93 G purified rodent diet (TestDiet, Richmond, IN) and tap water. During assays, three mice were housed together for 10 d in a single metabolic cage (Lab Products, Seagrove, DE) that separated urine and feces, and had unlimited access to test diet and drinking water. Mice were exposed to diet amended with sodium arsenate for the first 8 d, followed by unamended diet for 1 d. Urine and feces were collected daily and food consumption was measured daily. A cumulative urine sample was prepared for each metabolic cage by pooling of daily urine samples. For sample collection and data analysis, the unit of observation was the cage (i.e., excreta of three mice). Aliquots of cumulative urine samples and of test diets were processed for As analysis by instrumental neutron activation analysis (Bradham et al. 2011). The present study employed estimates of UEF for inorganic As obtained from multiple assays in which the test diet contained sodium arsenate or SRM 2710a. Sodium arsenate assays were performed between July 2009 and December 2014. Data from 50 metabolic cages were used to calculate UEF. An earlier analysis found that estimates of mean UEF for inorganic As over this period were highly stable with differences from the mean ranging from −17% to 14% (Bradham et al. 2020). RBA estimates for SRM 2710a-amended diets were obtained from a total of 16 metabolic cages from assays run repeatedly over the period August 2009 to February 2013.

Estimation of sodium arsenate ABA

A PK model was used to predict the fraction of the inorganic As dose excreted in feces (FEF) and urine (UEF) at an infinite time following cessation of As exposure (FEFinf and UEFinf). The PK model was based upon an empirical model (Equation 3) derived from repeated measurements of whole-body elimination of As from female C57BL/6 mice that received a single oral dose (0.5 mg As/kg) of 73As-labeled sodium arsenate (Drobna et al. 2009).

| (3) |

where BBt is the As body burden at time t after dosing, A is the fraction of initial body burden eliminated at rate α (h−1) and B is the fraction eliminated at rate β (h−1). Parameter values for the female C57BL6 mouse are as follows (Drobna et al. 2009): A = 0.1; α = 0.315 h−1; B = 0.03; β = 0.00766 h−1.

Equation 3 was the basis for creating a corresponding compartmental model, with the elimination components A and B assigned to two well-mixed sub-compartments of the body burden and with net transfer into the body compartment from the gastrointestinal compartment governed by an absorption fraction. Equations 4–8 describe the change of As mass in the gastrointestinal tract (GI), body burden (BB), excreted (EX), feces (FE), and urine (UR):

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where DO is the oral dose of arsenic (mg), af is the absorption fraction, fur is the fraction of the body burden excreted in urine and 1- fur is the fraction excreted in feces. The value for af was calibrated to achieve fit to the observed mean FEF and UEF measured on d 9 of the 8-d oral dosing studies (FEF9d, UEF9d). The calibrated value for af is the predicted ABA. This was verified in the model by demonstrating agreement between the calibrated af, the UEF at infinite time post-exposure (UEFinf), and ratio of the AUC for body burden (AUCBB) when the value of af was set to the calibrated value or 100% (Equation 9).

| (9) |

The model was implemented in Magnolia (v 1.3.9, magnoliasci.com). Confidence limits on the ABA were predicted assuming a standard normal distribution of means (z-score = 1.96) and with additional assumption that the coefficient of variation (CV = SD/mean) for UEFinf would be the same as the observed CV for UEF9d (Equation 10):

| (10) |

where SE is the standard error.

This analysis was extended to calculate the ABA of As in soil as the product of its RBA and the ABA for sodium arsenate (Equation 11):

| (11) |

A Monte Carlo analysis was utilized to estimate confidence limits on the ABAsoil from Equation 11, where variables for RBAsoil and ABAsodium arsenate were represented by the mean and standard error of their respective normal distributions.

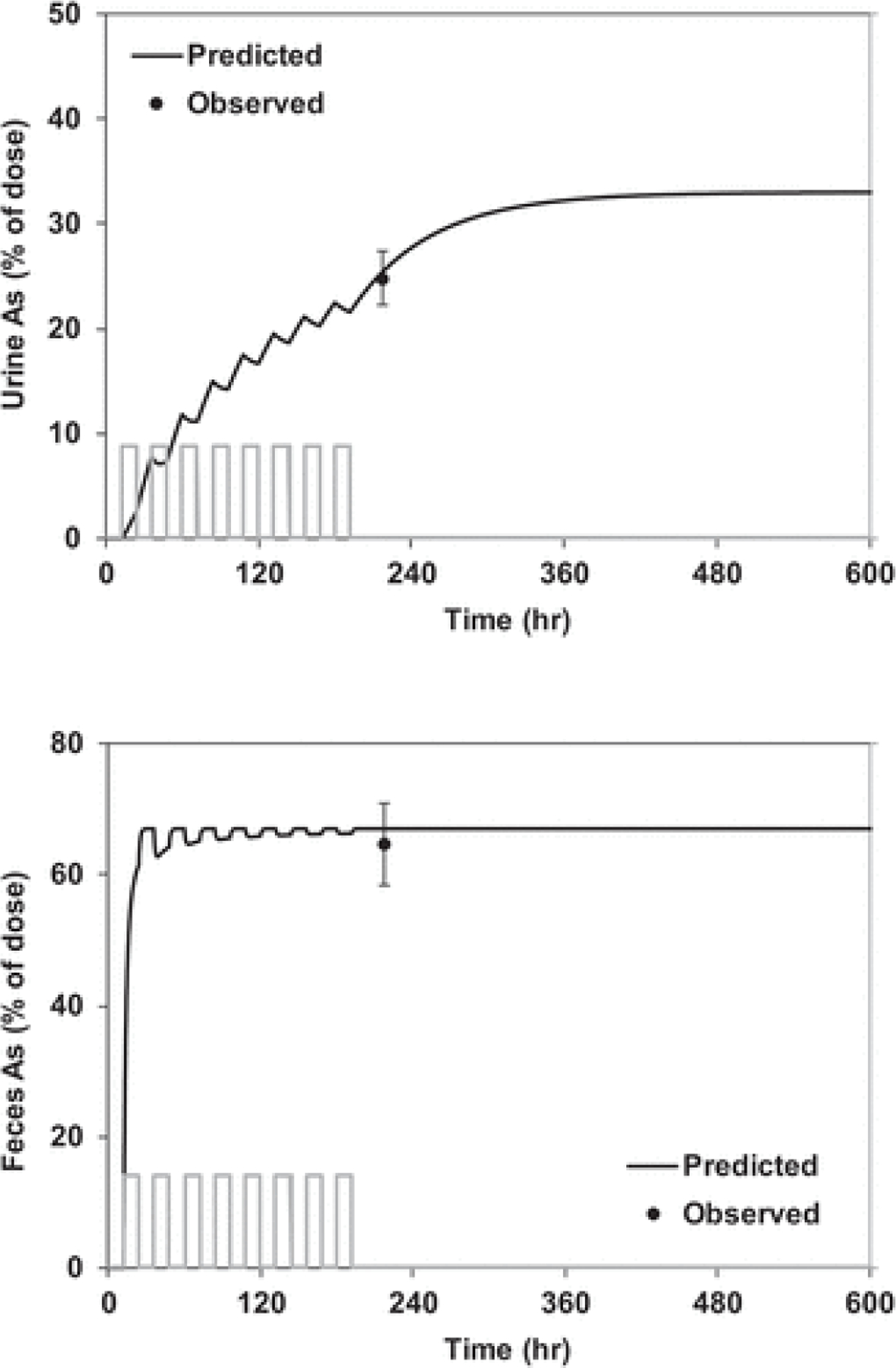

The utility of the PK model was evaluated using data from a study of female C57BL6 mice in which mice received nine daily oral gavage doses of 73As as arsenate and were observed for a period of 8 d following cessation of dosing (Hughes et al. 2003). The PK model predicted the observed fecal excretion of As, and overall pattern of urinary excretion (Figure 1). Differences between observed mean urinary excretion and model predictions may arise from use of an assumed mean body weight (0.025 kg) for each mouse; body weight data were not reported in Hughes et al. (2003). Based upon this assumed body weight, the cumulative fecal and urinary excretion of As were approximately 14% and 78% of the dose, respectively; and urinary As was 85% of combined urinary and fecal excretion (Hughes et al. 2003).

Figure 1.

Comparison of observed and predicted excretion kinetics in mice dosed with sodium 73As-arsenate. Observations are mean (n = 10 mice). The vertical bars represent dosing periods. Mice received daily oral gavage doses of 73As as sodium arsenate (0.5 mg As/kg bw/day) for a period of 9 d (Hughes et al. 2003). The simulation assumed an arsenic ABA of 85% and a mean body weight of 0.025 kg and approximately 0.0125 mg As/d (shown as bars at the bottom of each plot) for a cumulative dose of 4.5 mg As.

Results

Based upon studies conducted with 50 cages (3 mice per cage) of mice that consumed diet amended with sodium arsenate, the mean cumulative UEF9d for inorganic As was 63.8 ± 10.1% (SD), and the mean FEF9d was 15 ± 4.3% (SD). Notably, the UEF9d was independent of cumulative dose of sodium arsenate ingested by mice (range: 0.2–0.7 mg, r2 = 0.02). Figure 2 illustrates PK model-based simulations of % of the dose excreted in urine and feces and As body burden for mice that consumed diet amended with sodium arsenate for 8 d. The As body burden is predicted to reach approximately 97% of steady state by end of the eighth day of exposure. Diurnal oscillations in the body burden reflect the assumption that all food consumption occurred during successive 12-h dark periods (Ellacott et al. 2010). Calibration of af to achieve agreement with the observed UEF9d resulted in a value of 85%. For an af of 85%, the model predictions for UEF9d (65%) and FEF9d (15%) were comparable to observed values. The predicted UEFinf was 85% and FEFinf was 15%. When af was set to 85% or 100%, the body burden AUC ratio was also 85%, consistent with an ABA of 85%. Thus, the model predicts the cumulative urinary and fecal As excretion measured on d 9 if the ABA is 85%. The predicted SE of the mean ABA was 1.9% and the corresponding 95% confidence limits were 81–89%. The sensitivity of the predicted ABA to error in estimation of As elimination kinetics was evaluated. The predominant parameter that governs the rate of elimination is the α parameter (t1/2 4.4 h). Adjusting α ± 20% changed the predicted ABA ±5% (80–90%).

Figure 2.

Simulation of As excretion and body burden kinetics in mice fed a diet amended with sodium arsenate. Observations are mean ± SD (n = 50 cages of 3 mice per cage). Mice were exposed to sodium arsenate in the diet for a period of 8 d (3.0–7.6 µg As/g diet; cumulative dose 0.2–0.7 mg). The simulation assumed an As ABA of 85%, an average intake rate of 17 µg arsenic per mouse (approximately 0.3 mg/kg/d; 0.4 mg cumulative intake), and that all intake of dietary As occurred during a 12-h dark cycle (shown as bars at the bottom of each plot).

The ABA for sodium arsenate and the RBA for soil-borne As obtained in the mouse assay may be used to calculate the ABA for As in a test soil (Equation 11). Here, the ABA was calculated for As in SRM 2710a using an RBA value obtained from repeated mouse assays (mean = 38.9%; 95% CI: 35.7, 42.1; N = 5; Bradham et al. 2020). The corresponding ABA was 33% (95% CI: 31, 36). Figure 3 presents a model simulation of urinary and fecal excretion of As in mice that consumed a diet amended with SRM 2710a. The observed mean values were 24.8 ± 2.6% (SD) for UEF9d and 64.7 ± 6.3% for FEF9d. Assuming an ABA of 33%, the model predicts a UEF9d of 25% and FEF9d of 67%. The simulations shown in Figure 2 (sodium arsenate) and Figure 3 (SRM 2710a soil) assumed the same values for the parameters in the PK model that govern the elimination fraction of the As body burden excreted in urine (fur in Equation 2). Agreement between observed and predicted UEF for both materials suggests that fur was similar in mice exposed to As from diet amended with SRM 2710a soil or sodium arsenate. This provides further support for the use of Equation 2 for calculating RBA (i.e., fur,TM = fur,RM).

Figure 3.

Simulation of As excretion kinetics in mice fed a diet amended with sodium a SRM 2710a soil. Observations are mean ± SD (n = 20 cages of 3 mice per cage). The vertical bars represent dosing periods. Mice were exposed to diet amended with SRM 2710a for a period of 8 d (3.9–16.1 µg As/g diet; cumulative dose 0.3–1.2 mg). The simulation assumed an As ABA of 33%.

Table 1 compares estimates of the ABA for As obtained from mouse assays with estimates obtained in other species, including humans. Estimates of ABA in non-human species included a value derived from blood As AUC68hr in Cynomolgus monkeys (91.3 ± 12.4%; Freeman et al. 1995) and a value derived from UEF4d in Cebus monkeys (74.4 ± 4.8%; Roberts et al. 2002). Notably, similar estimates of the ABA for As were obtained in swine after administration of inorganic arsenate (88–104%) or arsenite (92–115%; Juhasz et al. 2006, 2007). Investigations in mice also demonstrated similar UEFs for As after administration of either arsenate (61.9 ± 4.6%) or arsenite (66.3 ± 2.8%; Bradham et al. 2013). In contrast, the UEF-derived estimate of ABA for arsenate (51–64%) obtained in rabbits (Freeman et al. 1993) was lower than ABA estimates in other species.

Table 1.

Summary of Estimates of Arsenic ABA in Humans and Animal RBA Models

| Animal Model | Dosing Method | ABA Metric | Mean ABA% | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | NaAsO2 in water | UEF14 d | 66% (9.3, SD, N = 4)a | Buchet, Lauwerys, and Roels 1981a |

| Human | As2O3 in water, oral/iv | Blood AUC24 h Plasma AUC24 h |

88% (49 SD, N = 9)b 111% (57 SD, N = 9) |

Kumana et al. 2002 |

| Human | Dietary | Fecal mass balance (7 d) | 87.5% (81.2, 93.8, N = 11) 89.7% (83.4, 96.0, N = 13) |

Stanek et al. 2010 |

| Human | Dietary plus high arsenic drinking water | Fecal mass balance (5 d) | 94.8% (2.3 SD, N = 6)c,d 93.8% (1.8, SD, N = 6)e 93.9% (2.6, SD, N = 6)f |

Zheng et al. 2002 |

| Monkey (Cynomolgus) | NaAsO4 in water, oral/iv | Blood AUC168 h | 91.3% (12.4 SE, N = 3) | Freeman et al. 1995 |

| Monkey (Cebus) | NaAsO4 in water, oral/iv | UEF4 d | 74.4% (4.8 SD, N = 4) | Roberts et al. 2002 |

| Swine (Large White) | NaAsO4 in water, oral/iv | Blood AUC26 h | 103.9% (28.8 SD, N = 3) 87.6% (14.6 SD, N = 3) |

Juhasz et al. 2006, Juhasz et al. 2007 |

| Swine (Large White) | Inorganic arsenite in water, oral/iv | Blood AUC26 h | 92.5% (22.3 SD, N = 3) 115.2% (40.6 SD, N = 3) |

Juhasz et al. 2006, Juhasz et al. 2007 |

| Rabbit (New Zealand White) | NaAsO4 in water, oral/iv | UEF5 d | 63.5 (male, N = 3)g 51.2 (female, N = 3) |

Freeman et al. 1993 |

| Mouse (C57BL6) | NaAsO4 added to diet | PK modeling of ABA calibrated to UEF9 d | 85% (81–89, N = 150)h | This study |

Calculated by authors as mean ± SD of dose groups (5 daily doses of 125, 250, 500, 1000 µg/d) reported in Table 1 of Buchet, Lauwerys, and Roels (1981a).

Calculated by authors as mean ± SD calculated for individual subject percent of intravenous AUC, reported in Table 2 of Kumana et al. (2002).

Reported in Table 4 of Zheng et al. (2002) based on repeated measurements made on same subjects at varying dose of ingested arsenic and varying arsenic and fluoride drinking water concentrations.

263 µg As/d, 0.15 mg As/L, 0.47 mg F/L.

645 µg As/d, 0.23 mg As/L, 2.25 mg F/L.

1146 µg As/d, 0.23 mg As/L, 4.05 mg F/L.

Variance metrics for ABA not reported.

Mean and 95% confidence interval of 50 cages of three mice per cage.

ABA, absolute bioavailability; AUC, area under the curve; iv, intravenous; N, number of animals; PK, pharmacokinetics; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; UEF, urinary excretion fraction.

Although studies in humans of oral bioavailability of soil-borne As are lacking, there are investigations in humans that examined the bioavailability of inorganic As after oral or iv administration. In selection of human studies for evaluation, it was necessary to exclude studies in which the observation times after exposure (e.g., ≤5 d) were not sufficient to ensure complete excretion of absorbed As (Buchet, Lauwerys, and Roels 1981b; Crecelius 1977; Mappes 1977; Tam et al. 1979). Studies that provided sufficient data included a study reporting the UEF14d in volunteers who ingested arsenite in drinking water (Buchet, Lauwerys, and Roels 1981a). Based upon half times for urinary elimination of As (range 39–59 h), the 14-d collection period should have recovered >98% of absorbed As excreted in urine. The mean UEF was 66 ± 9% (range: 54 to 74; N = 4). Kumana et al (2002) measured blood and plasma As AUC24hr in subjects who receiveda dose of 10 mg As trioxide by both the oral or iv route. The mean oral/iv AUC ratios were 88 ± 52% (SD, N=9) for blood As and 111 ± 57% (N=9) for plasma As.

Other studies in humans examined the bioavailability of As in other media including diet and water. A mass balance approach was used to estimate absorption of As from ingested food in adult humans (six females, five males; Stanek et al. 2010). In this investigation, As absorption was estimated from measurements of daily As intakes (based upon the duplicate diet samples) and cumulative excretion of As in feces and urine over a period of 7 d. This study consisted of two phases conducted several years apart. In the first phase, average dietary As intake was 81 µg/d and average absorption of As from food was 87.5% (95% CI: 81.2, 93.8). In the second phase, average dietary As intake was 31 µg/d and average absorption of As from food was 89.7% (95% CI: 83.4, 96.0). Zheng et al. (2002) examined As absorption in volunteers who consumed food and drinking water containing various levels of As. In these subjects, repeated estimates of average absorption of As were 94.8 ± 2.3% (SD), 93.8 ± 1.8% and 93.9 ± 2.6% at three As intake rates and levels of As and fluoride in drinking water, respectively (263 µg/d, 0.15 mg As/L, 0.47 mg F/L; 645 µg/d, 0.23 mg As/L, 2.25 mg F/L; 1146 µg/d, 0.23 mg As/L, 4.05 mg F/L). Zheng et al. (2002) reported that As in drinking water accounted for ≥80% of metalloid intake.

Discussion

Measurement of the bioavailability of soil-borne As is critical in assessing the health risks associated with ingestion of As (U.S. EPA 2012, 2020). Assessment of soil As bioavailability typically relies on use of animal models to supplement the small number of studies in humans that have assessed oral bioavailability of this metalloid (Bradham et al. 2018b). An assay that uses the lab mouse as the experimental species was used to assess the bioavailability of As in soils collected at U.S. EPA CERCLA sites, providing risk assessors and managers with information needed to guide site-specific remediation decisions (Bradham et al. 2020; Diamond et al. 2016).

Confidence in the mouse assay for estimating As oral bioavailability may be enhanced by comparing estimates obtained in humans and other animal models. Although the mouse RBA assay was not designed to measure the ABA for As, a PK modeling approach was used to estimate As ABA from the UEF data. This effort benefited from a large number of estimates of As RBA (N = 50) that were available from mouse assays conducted over a 3-year period. A PK model developed with data obtained in female C57BL6 mice that received single oral doses of sodium arsenate was used to predict the ABA of As in mice that ingested a sodium arsenate-amended diet. Utilization of data from strain- and sex-matched mice in model development increased confidence in the relevance of the model for ABA prediction. Based upon the PK model, verification of the predicted ABA with direct measurement of UEFinf requires a post-exposure observation period of at least 9 d to ensure complete (99%) excretion of the absorbed dose. These results were consistent with previous studies of the excretion of 73As in adult female C57BL6 mice following repeated days of oral gavage dosing with 73As-arsenate (Hughes et al. 2010, 2003). In these investigations, time to steady state was estimated to be approximately 9 d. Over this exposure period, cumulative fecal and urinary excretion of were approximately 14% and 78% of the dose, respectively, and urinary As accounted for 85% of combined urinary and fecal excretion of As.

Accurate prediction from the PK model of the observed pre-steady state UEF9d also provides further validation of the post-absorption elimination kinetics in female C57BL6 mice reported earlier (Drobna et al. 2009). The accuracy with which the PK model represented the absorption and urinary elimination kinetics in the 150 mice included in the present study supports the generalizability of the PK model to this inbred strain, which would be expected to exhibit lower biological variability than outbred strains used in other animal models. The finding that observed UEF9d in mice exposed to diet amended with sodium arsenate or SRM 2710a soil might be accurately predicted from the same elimination model suggests that As elimination kinetics was similar in these two exposures. Our data support the validity of calculating As RBA from the UEF9d ratio. An important uncertainty needs to be noted in application of the PK model to estimate ABA. The model assumes that the entire absorbed dose would be excreted in urine (fur = 1). This assumption may introduce a downward bias in the ABA estimate. For example, studies of mice exposed to inorganic As demonstrated retention of absorbed As in deep reservoirs in keratinaceous tissues (Hughes et al. 2003; Kenyon et al. 2008); this pattern of disposition may influence the fraction of the dose available for urinary clearance. In addition, biliary secretion of both inorganic As and monomethyl As demonstrated in mice treated with arsenate (Csanaky and Gregus 2002) creates an unquantified pathway for enterohepatic recycling of As in mice that is not represented in our PK model.

Our estimate of the ABA of inorganic As from the mouse model (85%) is consistent with estimates obtained in humans who ingested inorganic As (66–100%; Buchet, Lauwerys, and Roels 1981a; Kumana et al. 2002) and in humans exposed to arsenic in the diet (88–95%; Stanek et al. 2010; Zheng et al. 2002). Human studies involving exposure to As in food may be affected by the variety of arsenicals present in foods, including methylated arsenicals and a variety of complex organic arsenicals that are constituents of many foods (Thomas and Bradham 2016; Wolle, Stadig, and Conklin 2019). Thus, ABA estimates derived from these studies might be affected by differences in oral bioavailability of the constituent As-containing species and may not be directly comparable to results obtained in investigations in other species in which the chemical form of ingested As (e.g., inorganic As) was known. Our estimate of the inorganic As ABA from the mouse model is also consistent with estimates obtained in monkeys and swine, which ranged from 74% to 100% (Freeman et al. 1995; Juhasz et al. 2006, 2007; Roberts et al. 2002).

Conclusions

In sum, our analysis suggests that ABA of sodium arsenate in the mouse model is similar to ABA estimates for humans and other animal models. The result (ABA = 85%) provides further support for use of the mouse model in human health risk assessment and further validation of a previously reported PK model of inorganic As in the C57BL/6 mouse model (Drobna et al. 2009). The congruence of values obtained in mouse and humans provides further support for the use of the mouse model for predicting As RBA in humans and its application to human health risk assessment of soil-borne As. A future research objective would be to compare soil As ABAs or RBAs obtained from the mouse model with estimates in humans for the same soils. In vivo RBA models continue to be essential for developing and refining in vitro bioaccessibility (IVBA) assays that provide less expensive approaches to predicting soil arsenic RBA. In addition, having an estimate of the ABA for sodium arsenate obtained in the mouse model, data on the RBA of As in a soil may be used to calculate the ABA of As in a soil. Data from these analyses may be used to support development of exposure-biokinetics models of soil arsenic that would require values for the gastrointestinal absorption fraction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation (OSRTI), under Contract 68HERH19D0022. We are grateful for valuable input on Magnolia code from Conrad Housand of Magnolia Sciences.

Funding

This work was supported by the [US Environmental Protection Agency Contract 68HERH19D0022].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Disclaimer

The manuscript has been reviewed in accordance with EPA policy and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that content necessarily reflects views and policies of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this publication are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 2007. Toxicological profile for arsenic U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Atlanta, GA: 559 p. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 2016. Addendum to the toxicological profile for arsenic. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences. Atlanta, GA: 189 p. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/Arsenic_addendum.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradham KD, Scheckel KG, Nelson CM, Seales PE, Lee GE, Hughes MF, Miller BW, Yeow A, Gilmore T, Harper S, et al. 2011. Relative bioavailability and bioaccessibility and speciation of arsenic in contaminated soils. Environ. Health. Perspect 119:1629–34. 10.1289/ehp.1003352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradham KD, Diamond GL, Scheckel KG, Hughes MF, Casteel SW, Miller BW, Klotzbach JM, Thayer WC, and Thomas DJ 2013. Mouse assay for determination of arsenic bioavailability in contaminated soils. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 76:815–26. 10.1080/15287394.2013.821395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradham K, Diamond G, Juhasz A, Nelson C, and Thomas D 2018a. Comparison of mouse and swine bioassays for determination of soil arsenic relative bioavailability. Appl. Geochem 88:221–25. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2017.05.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradham KD, Diamond GL, Burgess M, Juhasz A, Klotzbach JM, Maddaloni M, Nelson C, Scheckel K, Serda SM, Stifelman M, et al. 2018b. In vivo and in vitro methods for evaluating soil arsenic bioavailability: Relevant to human health risk assessment. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 21:83–114. 10.1080/10937404.2018.1440902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradham KD, Herde C, Herde P, Juhasz A, Herbin-Davis K, Elek B, Farthing A, Diamond GL, and Thomas DJ 2020. Intra- and inter-laboratory evaluation of an assay of soil arsenic relative bioavailability in mice. J. Agric. Food. Chem 68:2615–22. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brattin W, and Casteel S 2013. Measurement of arsenic relative bioavailability in swine. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 76:449–57. 10.1080/15287394.2013.771562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchet JP, Lauwerys R, and Roels H 1981a. Urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic and its metabolites after repeated ingestion of sodium metaarsenite by volunteers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 48:111–18. 10.1007/BF00378431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchet JP, Lauwerys R, and Roels H 1981b. Comparison of the urinary excretion of arsenic metabolites after a single oral dose of sodium arsenite, monomethylarsonate, or dimethylarsinate in man. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 48:71–79. 10.1007/BF00405933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crecelius EA 1977. Changes in the chemical speciation of arsenic following ingestion by man. Environ. Health Perspect 19:147–50. 10.1289/ehp.7719147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Csanaky I, and Gregus Z 2002. Species variation in the biliary and urinary excretion of arsenate, arsenite and their metabolites. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol 131:335–65. 10.1016/S1532-0456(02)00018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis A, Ruby MV, Bloom M, Schoof R, Freeman G, and Bergstrom PD 1996. Mineralogic constraints on the bioavailability of arsenic in smelter-impacted soils. Environ. Sci. Technol 30:392–99. 10.1021/es9407857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond GL, Bradham KD, Brattin WJ, Burgess M, Griffin S, Hawkins CA, Juhasz AL, Klotzbach JM, Nelson C, Lowney YW, et al. 2016. Predicting oral relative bioavailability of arsenic in soil from in vitro bioaccessibility. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 79:165–73. 10.1080/15287394.2015.1134038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drobna Z, Narenmandurs H, Kubachka KM, Edwards BC, Herbin-Davis K, Styblo M, Le XC, Creed JT, Maeda N, Hughes MG, et al. 2009. Disruption of the arsenic (+3 oxidation state) methyltransferase gene in the mouse alters phenotype for methylation of arsenic and affects distribution and retention of orally administered arsenate. Chem. Res. Toxicol 22:1713–20. 10.1021/tx900179r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellacott KL, Morton GJ, Woods SC, Tso P, and Schwartz MW 2010. Assessment of feeding behavior in laboratory mice. Cell Metab 12:10–17. 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman GB, Johnson JD, Killinger JM, Liao SC, Davis AO, Ruby MV, Chaney RL, Lovre SC, and Bergstrom PD 1993. Bioavailability of arsenic in soil impacted by smelter activities following oral administration in rabbits. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol 21:83–88. 10.1006/faat.1993.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman GB, Schoof RA, Ruby MV, Davis AO, Dill JA, Liao SC, Lapin CA, and Bergstrom PD 1995. Bioavailability of arsenic in soil and house dust impacted by smelter activities following oral administration in cynomolgus monkeys. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol 28:215–22. 10.1006/faat.1995.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes MF, Kenyon EM, Edwards BC, Mitchell CT, Del Razo LM, and Thomas DJ 2003. Accumulation and metabolism of arsenic in mice after repeated oral administration of arsenate. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 191:202–10. 10.1016/S0041-008X(03)00249-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes MF, Edwards BC, Herbin-Davis KM, Saunders J, Styblo M, and Thomas DJ 2010. Arsenic (+3 oxidation state) methyltransferase genotype affects steady-state distribution and clearance of arsenic in arsenate-treated mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 249:217–23. 10.1016/j.taap.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes MF, Beck BD, Chen Y, Lewis AS, and Thomas DJ 2011. Arsenic exposure and toxicology: A historical perspective. Toxicol. Sci 123:305–32. 10.1093/toxsci/kfr184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 2012. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. No. 100C (Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts) Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juhasz AL, Smith E, Weber J, Naidu R, Rees M, Rofe A, Kuchel T, Sansom L, and Naidu R 2006. In vivo assessment of arsenic bioavailability in rice and its significance for human health assessment. Environ. Health Perspect 114:1826–31. 10.1289/ehp.9322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juhasz AL, Smith E, Weber J, Naidu R, Rees M, Rofe A, Kuchel T, Sansom L, and Naidu R 2007. Comparison of in vivo and in vitro methodologies for the assessment of arsenic bioavailability in contaminated soils. Chemosphere 69:961–66. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenyon EM, Hughes MF, Adair BM, Highfill JH, Crecelius EA, Clewell HJ, and Yager JW 2008. Tissue distribution and urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic and its methylated metabolites in C57BL6 mice following subchronic exposure to arsenate in drinking water. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 232:448–445. 10.1016/j.taap.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumana CR, Au WY, Lee NSL, Kou M, Mak RWM, Lam CW, and Kwong YL 2002. Systemic availability of arsenic from oral arsenic-trioxide used to treat patients with hematological malignancies. Eur. J. Pharmacol 58:521–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Li C, Sun H-J, Juhasz AL, Luo J, Li H-B, and Ma LQ 2016. Arsenic relative bioavailability in contaminated soils: Comparison of animal models, dosing schemes, and biological endpoints. Environ. Sci. Technol 50:453–61. 10.1021/acs.est.5b04552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H-B, Ning H, Li S-W, Li J, Xue R-Y, Li M-Y, Wang M-Y, Liang J-H, Juhasz AL, and Ma LQ 2021. An interlaboratory evaluation of the variability in arsenic and lead relative bioavailability when assessed using a mouse assay. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 84:593–607. 10.1080/15287394.2021.1919947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mappes R 1977. Experiments on excretion of arsenic in urine. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 40:267–72. 10.1007/BF00381415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murko M, Elek B, Styblo M, Thomas DJ, and Francesconi KA 2018. Dose and diet – Sources of arsenic intake in mouse in utero exposure scenarios. Chem. Res. Toxicol 31:156–64. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odezulu NG, Lowney YW, Portier KM, Kozuch M, Bacon AR, Roberts SM, and Suchal LD 2022. Effect of sol particle and extraction method on the oral bioaccessibility of arsenic. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 85:538–52. 10.1080/15287394.2022.2048935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves PGPG, Nielsen FH, and Fahey GC 1993. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: Final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr 123:1939–51. 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rehman MU, Khan R, Khan A, Qamar W, Arafah A, Ahmad P, Ahmad P, Ahmad P, Ahmad P, and Ahmad P 2021. Fate of arsenic in living systems: Implications for sustainable and safe food chains. J. Hazard. Mater 417:126050. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts SM, Weimar WR, Vinson JR, Munson JW, and Bergeron RJ 2002. Measurement of arsenic bioavailability in soil using a primate model. Toxicol. Sci 67:303–10. 10.1093/toxsci/67.2.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts SM, Munson JW, Lowney YW, and Ruby MV 2007. Relative oral bioavailability of arsenic from contaminated soils measured in the Cynomolgus monkey. Toxicol. Sci 95:281–88. 10.1093/toxsci/kfl117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanek EJ, Calabrese EJ, Barnes RM, Danku JMC, Zhou Y, Kostecki PT, and Zillioux E 2010. Bioavailability of arsenic in soil: Pilot study results and design considerations. Human. Exp. Toxicol 29:945–60. 10.1177/0960327110363860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tam GKH, Charbonneau SM, Bryce F, Pomroy C, and Sandi E 1979. Metabolism of inorganic arsenic (74As) in humans following oral ingestion. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 50:319–22. 10.1016/0041-008X(79)90157-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas DJ, and Bradham K 2016. Role of complex organic arsenicals in food in aggregate exposure to arsenic. J. Environ. Sci 49:86–96. (China). 10.1016/j.jes.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2012. Compilation and review of data on relative bioavailability of arsenic in soil Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response. OSWER 9200.1–113. https://www.epa.gov/superfund/soil-bioavailability-superfund-sites-guidance [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2020. Guidance for sample collection for in vitro bioaccessibility assay for arsenic and lead in soil and applications of relative bioavailability data in human health risk assessment Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response. OSWER 9200.3–100a. https://www.epa.gov/superfund/soil-bioavailability-superfund-sites-guidance [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2021. Arsenic, inorganic (CASRN 7440–38-2). Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Accessed July 19 2021. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/subst/0278_summary.pdf#nameddest=rfd

- 42.WHO (World Health Organization). 2011. Arsenic in drinking water. Background document for development of WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. WHO/SDE/WSH03.04/75.rev1 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolle MM, Stadig S, and Conklin SD 2019. Market basket survey of arsenic species in the top ten most consumed seafoods in the United States. J. Agric. Food Chem 67:8253–67. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b02314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y, Wu J, Ng JC, Wang G, and Lian W 2002. The absorption and excretion of fluoride and arsenic in humans. Toxicol. Lett 133:77–82. 10.1016/S0378-4274(02)00082-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this publication are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.