Abstract

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) has been used for long-acting injectable drug delivery systems for more than 30 years. The factors affecting the properties of PLGA formulations are still not clearly understood. The drug release kinetics of PLGA microparticles are influenced by many parameters associated with the formulation composition, manufacturing process, and post-treatments. Since the drug release kinetics have not been explainable using the measurable properties, formulating PLGA microparticles with desired drug release kinetics has been extremely difficult. Of the various properties, the glass transition temperature, Tg, of PLGA formulations is able to explain various aspects of drug release kinetics. This allows examination of parameters that affect the Tg of PLGA formulations, and thus, affecting the drug release kinetics. The impacts of the terminal sterilization on the Tg and drug release kinetics were also examined. The analysis of drug release kinetics in relation to the Tg of PLGA formulations provides a basis for further understanding of the factors controlling drug release.

Keywords: glass transition temperature, PLGA, microparticles, nanoparticles, drug release kinetics, terminal sterilization

1. DRUG RELEASE FROM PLGA MICROPARTICLES

The goal of drug formulation development varies, but ultimately it is about developing a system that is safe and effective for clinical use after approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To this end, it is desirable to develop formulations based on the Quality by Design (QbD) approach. The formulation development begins with constructing predefined objectives or the quality target product profile (QTPP), translating into the critical quality attributes (CQAs), ensuring both safety and efficacy. Designing the process for product development and manufacturing requires a systematic examination of the critical material attributes (CMAs) and critical process parameters (CPPs).1 Both CMAs and CPPs require understanding the process and the representative factors that control the process. However, a lack of mechanistic understanding and control often exists in the scale-up and manufacturing of injectable, long-acting formulations, particularly PLGA microparticles. It has made the development and manufacturing of PLGA microparticles with desired drug release profiles difficult.2 Understanding the exact mechanisms of drug release from PLGA-based drug delivery systems will lead to deciphering the factors that affect the drug release,3 and thus, designing PLGA microparticles with predetermined drug release rates.

1.1. Factors Affecting the Drug Release Kinetics.

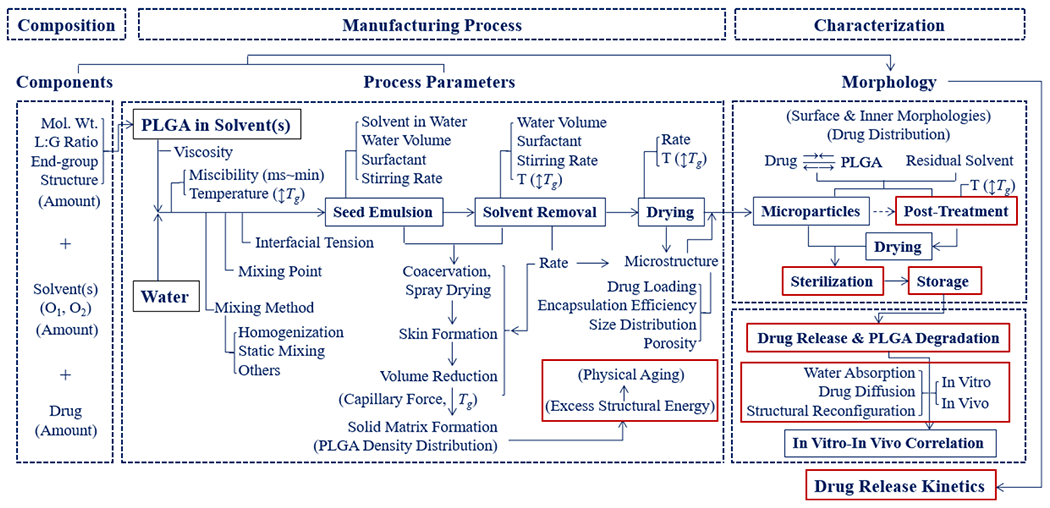

A large number of variables in CMAs (i.e., compositions) and CPPs (i.e., manufacturing process and storage) affect the QTPP (i.e., drug release kinetics) of PLGA formulations, as described in Figure 1. Several process parameters in Figure 1 were examined previously.4 Here, our analysis is focused on a few specific parameters, as highlighted with red boxes in Figure 1, with emphasis on the importance of the glass transition temperature (Tg) on the drug release properties of PLGA microparticles and nanoparticles. For convenience, the term “microparticles” includes “nanoparticles” unless specified otherwise. PLGA microparticles discussed here are all prepared by emulsion methods or spray drying methods.

Figure 1.

A flowchart describing the manufacturing of PLGA microparticles and the parameters affecting the properties of the formulation (modified from ref 4).

2. GLASS TRANSITION TEMPERATURE AND DRUG RELEASE

The Tg of PLGA polymers has been measured routinely, but the Tg of PLGA formulations has not been reported in the literature as frequently. It is perhaps because its impact on the formulation properties, in particular drug release kinetics, has been underappreciated. The Tg of PLGA formulations, however, provides essential information on the drug release properties. For convenience, Tg in this article will refer to the Tg of PLGA microparticle formulations, unless specially mentioned for PLGA raw polymers.

2.1. Glass Transition by a Temperature Drop and by Solvent Removal.

PLGA microparticles are most commonly prepared using emulsion-based processing. PLGA polymers dissolved in organic solvents become hardened as the solvent is extracted. The formation of glassy PLGA through solvent extraction is analogous to the glass transition induced by lowering the temperature from the rubbery state. Thus, the removal of solvents can be considered to be equivalent to the lowering of the temperature below Tg.2 It is also similar to removing water from a hydrophilic polymer solution to induce a glass transition.5 However, there is a subtle difference between the two phenomena. Through cooling to temperatures below the Tg, the segmental motions in the PLGA chains are arrested. During isothermal solvent extraction, however, the motion in PLGA chains is minimized at different rates depending on their location in the emulsion oil droplet through microparticle hardening. Solvent molecules have to diffuse over the radius of microparticles, i.e., distances much larger than their respective size to equilibrate, requiring a longer time scale than the temperature-induced glass transition.6 As a solvent is removed from PLGA microemulsion droplets, the PLGA polymers of higher molecular weight and the regions of higher PLGA concentration start to precipitate (i.e., become glassy), leading to localized higher chain densities. It forms the overall network structure of microparticles with heterogeneous local densities. This may be critical to drug release properties. Another factor that complicates the formation of glassy PLGA microparticles is that the glass starts to form under shear stress applied to form microemulsion droplets. The stress applied during vitrification of the glass is known to leave the system with higher energy, i.e., less stable state, and increase its physical aging rate.7 Solvent extraction also involves water uptake into the polymeric matrix, where water also acts as a plasticizer decreasing the Tg. This water is then removed during vacuum-drying or freeze-drying (lyophilization). The solvent removal rate, the quantity of residual solvent and water, and the temperature of water for solvent extraction and washing also contribute to the final energetic state of the polymeric-drug matrix. As the extraction temperature increases, the polymer chains spend a greater duration of time above the Tg. This results in prolonged polymer molecule flexibility where drug molecules can diffuse into the external phase resulting in a decrease in encapsulation efficiency. A decrease in encapsulation efficiency with increasing extraction temperature was noted for risperidone8 and huperzine-A.9 The final drying may also include a type of annealing process, and thus, the drying temperature of the microparticles, at or around the Tg, also needs to be carefully controlled.

The solvent removal rate is analogous to the temperature cooling (or quenching) rate. Faster solvent removal results in the formation of glassy PLGA blocks with higher excess energy than that obtained by slower solvent removal. The effect of excess energy on the properties of PLGA microparticles can be explained by the enthalpy-temperature relation diagrams used in glass-forming polymers. PLGA polymers in the glassy state with excess energy undergo continuous relaxation to attain structural equilibrium.10 The rearrangement of polymer chains leads to changes in physical properties, such as morphology, porosity, size, free volume, and local density. Such changes in the physical state can significantly affect the drug release properties, depending on the formulation and the storage conditions.11

2.2. Glass Transition of PLGA Microparticles.

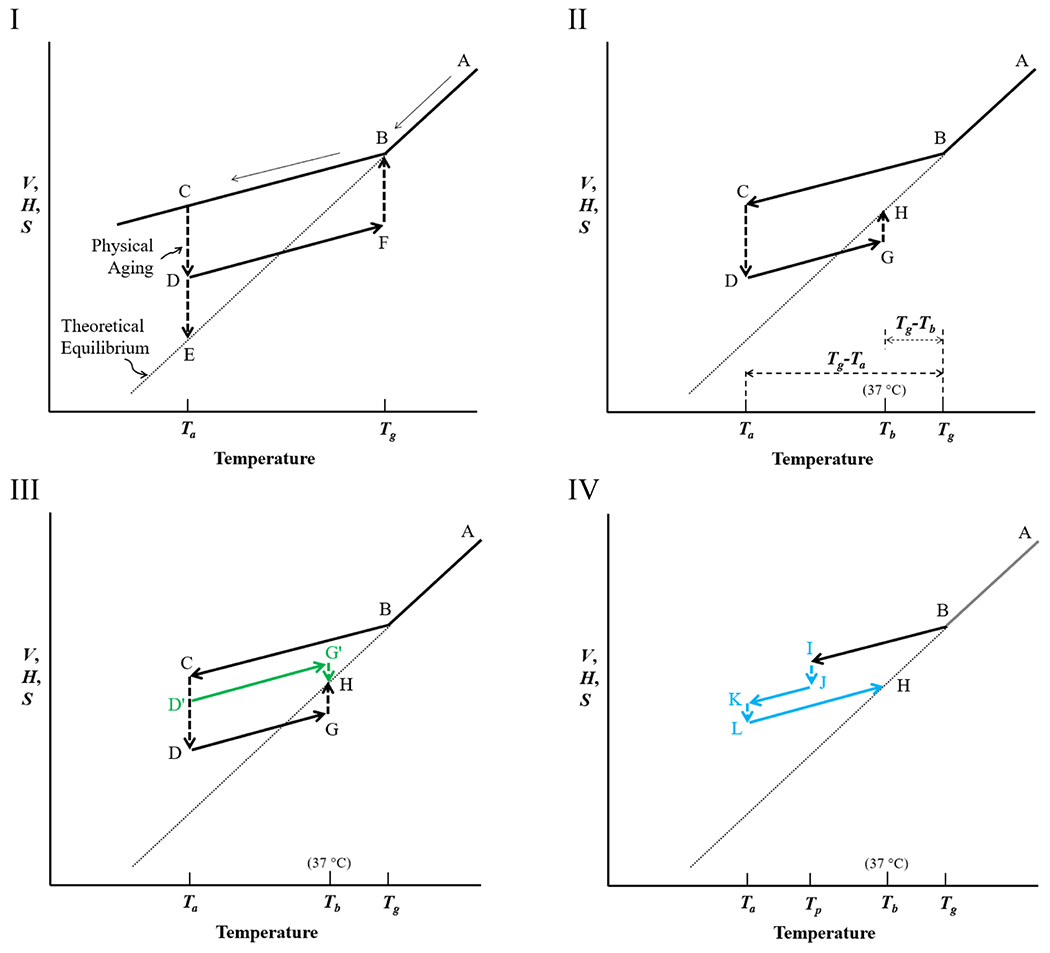

Figure 2I–IV show the volume–temperature relationship relevant to understanding the rubbery to glassy state in a PLGA polymer. The volume (V) in Figure 2 can be replaced with enthalpy (H) or entropy (S). The volume is used here because it is a more relevant parameter in discussing the PLGA microparticles. The volume here refers explicitly to the free volume (VF) described in detail below. Amorphous polymers at temperatures between their Tg and melting temperature (Tm) (A in Figure 2) are in a rubbery state, and it transitions to a glassy state below Tg. Amorphous solids (B,C in Figure 2) at temperatures below their Tg are regarded as solidified supercooled liquids that are not in thermodynamic equilibrium (C, D in Figure 2I).12 A nonequilibrium glass is obtained because the supercooled liquid cannot rearrange fast enough to reach an equilibrium in the time scale of the experiment.13 Thus, Tg depends on the cooling rate. The thermodynamic equilibrium of an ideal glassy state (line B–E) can be obtained only by an infinitely slow cooling rate, and thus, it is often called the theoretical equilibrium.14 The V, H, and S of amorphous solids are larger than they would be in the equilibrium supercooled liquid state at the same temperature.12,14

Figure 2.

Volume (V) (or enthalpy (H), or entropy (S)) as a function of temperature for PLGA microparticles. (Temperature can be replaced with solvent fraction). (I) As the equilibrium liquid (A) is cooled, the liquid becomes glassy (B) at Tg. At the annealing temperature, Ta, the volume of the system (C) is lowered (D) to reach an equilibrium glassy state (E). As the aged glass (D) is heated to the Tg, the volume increases to F and then to B, an equilibrium rubbery state. (II) When the aged glass (D) is heated to 37 °C, body temperature, Tb, the volume rises to G and reaches an equilibrium state (H). The times for physical aging (C → D) and for reaching equilibrium at Tb (G → H) depend on the magnitude of Tg-Ta, and Tg-Tb, respectively. (III) At Ta, physical aging occurs to different extents, D′ or D, depending on the aging time. When the temperature is raised to Tb, G’ or G reaches the equilibrium state H. (IV) The prepared glassy PLGA microparticles (I) may be exposed again to a poor solvent (e.g., ethanol) at the temperature of preparation (Tp), and the volume is reduced (J), then dried again, and stored at Ta (K). The glassy PLGA may undergo further aging to L before the temperature is increased again to Tb.

2.3. Physical Aging (or Structural Relaxation).

PLGA polymer chains in the glassy state undergo slow relaxation processes trying to reach a thermodynamic equilibrium glassy state. This gradual change below Tg to equilibrium (C–E in Figure 2I) is called physical aging. Physical aging is also called structural relaxation, energetic relaxation, enthalpy relaxation, or structural recovery.2,12,15,16 The term “physical” has been used to distinguish from “chemical” or “biological” aging and to indicate only reversible changes in properties.12,17,18 Physical aging is mainly characterized by a decrease in volume to the equilibrium volume. Physical aging is usually slow, and reaching the ultimate thermodynamic equilibrium, E, is practically not achievable.12,17 Thus, aging usually refers to reaching D, a relative thermodynamic equilibrium.13 As the temperature is increased from Ta to Tg (D → F) in Figure 2I, the enthalpy gain follows the same slope as line BC because the heat capacity of the glassy state before and after aging is assumed to be the same over the experimental range of Tg.19,20

In the absence of any external influences, the change in polymer physical behavior is a function of aging time. Since PLGA formulations are usually stored at a given temperature without external disturbances, the storage time can be treated as an aging time. The change in free volume due to structural relaxation depends on the processing and aging temperature.21 Physical aging results from the slow dissipation of the internal energy of the polymer toward equilibrium, and thus, the rate of physical aging depends on temperature and the amount of excess structural energy in the system.2 Physical aging makes the polymer matrix stiffer and more brittle, as random coil polymers of the amorphous glass undergo a macroscopic volume contraction or microscopic heterogeneous fluctuations forming void spaces.16,22 Thus, physical aging can alter the end-use properties, such as increased modulus, increased brittleness, and altered permeability.15

As the temperature is increased to Tb (Figure 2II), volume recovery occurs from G to H. During aging, the actual path for change depends on the aging temperature and condition. Thus, the volume reduction can be either C → D′ or C → D (Figure 2III). Figure 2IV describes volume changes of the dried PLGA microparticles by post-treatment. The PLGA microparticles after drying are at the glassy state, I. They are sometimes dispersed in a solvent (e.g., ethanol) again, known as post-treatment, at temperature Tp, and PLGA polymers can go through the aging process to lower the volume to J. After post-treatment, the microparticles are dried and stored at Ta (e.g., 4 °C), and the aging process continues (K → L). An excellent example of post-treatment is the washing of “dried” PLGA microparticles with ethanol solution followed by the second drying.8,23–25

2.4. Physical Aging of PLGA Microparticles.

The drug release kinetics from PLGA microparticles is related to the Tg of the formulations. Physical aging occurs within the temperature range between Tg and the secondary transition, Tβ, which is associated with the subsegmental relaxation, known as β-relaxation.12 This β-relaxation process has been attributed to the local rotation of C–O macromolecular chain segments, where the α-relaxation is due to the segmental motion of the copolymer backbone.26 The secondary transition temperatures for PLGA polymers range from −137 °C to −30 °C,26 and thus, PLGA polymers undergo physical aging as long as the formulations are stored at or above −30 °C. Because most formulations are stored at 4 °C or room temperature, it is expected that physical aging still occurs. The aging time is as crucial as other parameters, such as temperature and humidity during storage, and aging can be explained from the free volume concept.12 The time (t∞) to reach the thermodynamic equilibrium at any given temperature, T, can be estimated from the following equation:

| (1) |

where t∞ is in seconds and temperatures are in °C.12 If a formulation is annealed or stored at temperatures more than 18 °C lower than Tg (i.e., Tg-Ta > 18 °C), full relaxation will require prolonged storage times.27 In these cases, the PLGA formulations approved by the FDA typically do not reach their thermodynamic equilibrium during a two-year shelf life of a PLGA formulation (i.e., t∞ > 2 years). Equation 1 also indicates that t∞ is reduced to 1 day if Ta is less than 9 °C away from Tg. In the body, the presence of water, surfactants, proteins, and enzymes is likely to depress the Tg to temperatures near or below 37 °C (i.e., body temperature). If Tg-Tb < 7 °C, the PLGA formulation will reach an equilibrium in 6 h (Figure 3). The Tg of PLGA polymers has been shown to decrease by 15 °C in an hour as the polymers absorb water and surfactants.28,29 The Tg of PLGA polymers is known to decrease linearly at a rate of 6.03 ± 0.57 °C per mass % of water absorbed.18 Thus, it is likely that the Tg-Tb is close to 0 °C, and equilibrium will be reached within an hour.

Figure 3.

Equilibrium time (t∞) as a function of the difference between the glass transition and storage temperatures (Tg-T) of PLGA microparticles. Inset: t∞ in hours as a function of Tg-T for the first 10 °C difference.

The Tg of PLGA polymers depends on its L:G ratio and molecular weight, and Table 1 lists the range of Tg values of commonly used PLGA polymers with different L:G ratios. Depending on the physicochemical properties of each PLGA, the actual Tg value of each PLGA polymer may be outside of the typical ranges in Table 1. Thus, the data in the table should be taken just to indicate that the Tg value increases as the L:G ratio increases. For example, measured Tg values of PLGA 65:35, 75:25, and 100:0 were 40–42, 44–45, and 33–46 °C, respectively,30 much lower than the range described in Table 1. The Tg value depends on experimental methods, including a heating rate, and the polymer properties, such as polymer molecular weight and crystallinity. (Molecular weights are described in kDa, and they represent the weight-average molecular weight, unless specified otherwise.)

Table 1.

Glass Transition Temperatures (Tg) of PLGA Polymers31

| L:G ratio | 50:50 | 65:35 | 75:25 | 85:15 | 100:0 |

| Tg (°C) | 45–50 | 45–50 | 50–55 | 50–55 | 50–65 |

The Tg decreases further in the presence of a drug due to its plasticizing effect when dispersed throughout the polymeric matrix. For example, the Tg of Resomer PLGAs decreased as the indomethacin weight fraction was increased. Table 2 shows examples of the decrease in Tg of PLGAs with the 20% indomethacin compositions prepared by ball milling.32 It is noted that some drugs may have an antiplasticizing effect, and thus, can increase the Tg of PLGA formulations. Leuprorelin acetate increased the Tg of PLGA microparticles.33 The Tg values measured in this study were generally lower than those described from the manufacturer’s website.34 The Tg values decrease even further when the PLGA microparticles are injected into the body due to the penetration of the body fluids into the polymer network.35

Table 2.

Decrease in Tg of PLGA Polymers in the Presence of 20% Indomethacin32

| Resomer | L:G ratio | molecular weight (kDa) | Tg (°C) | Tg with drug (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG 502 S | 50:50 | 13 | 32.74 | 30.35 ± 0.50 |

| RG 752 S | 75:25 | 1 | 35.82 | 25.05 ± 1.00 |

| RG 755 S | 75:25 | 68 | 46.74 | 39.75 ± 0.70 |

| RG 756 S | 75:25 | 103 | 49.76 | 42.65 ± 0.10 |

| RG 750 S | 75:25 | 128 | 49.00 | 40.65 ± 5.20 |

Polymer molecules near the surface have enhanced mobility, and thus, relax toward an equilibrium state more rapidly than bulk polymers.36,37 If the relaxation occurs relatively quickly, physical aging at the air–polymer interface may appear absent.15,38 It also implies that physical aging is not homogeneous throughout the PLGA matrix and varies across the microparticles. This has an important implication in the drug release from PLGA microparticles.

2.5. Physical Aging and the Free Volume.

The initial burst release has been commonly explained by the dissolution of the drug present on and/or near the surface. This simple, easy explanation, however, requires further examination. The prepared microparticles are thoroughly washed before drying, and so the release of drug present on the surface may not constitute the majority of the initial burst release.39,40 Thus, a new explanation is warranted.

The importance of physical aging in glassy PLGA microparticles is that it may change the PLGA matrix structure, ultimately affecting the release of drug molecules from a formulation.2 Now, the question is how physical aging impacts the properties of PLGA formulations, in particular, the extent of burst release and the rate of steady-state release. Here, the concept of the free volume (VF) and its link to mobility is relevant to the drug release kinetics.

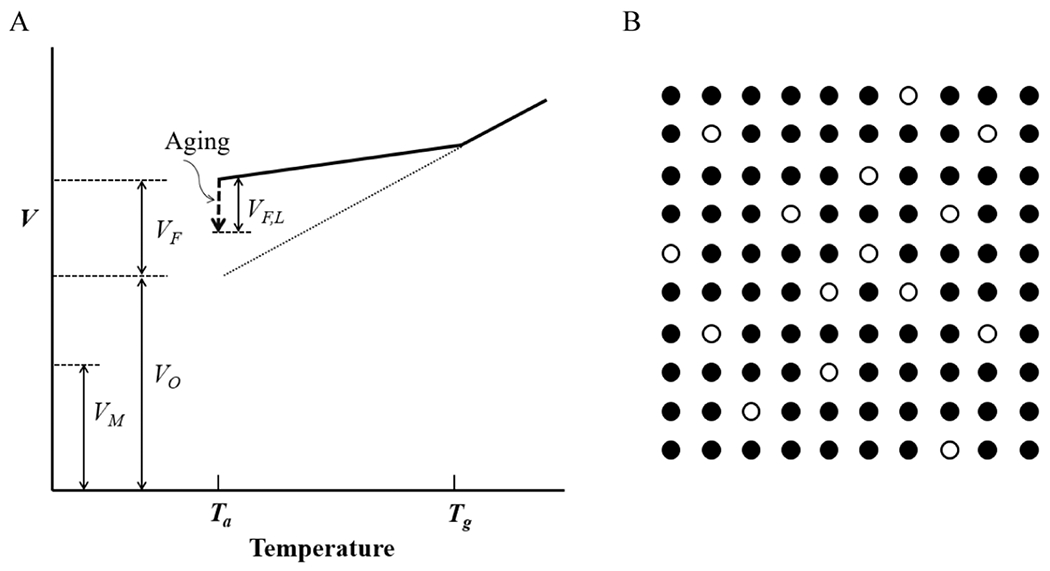

The molecular volume (VM), also called van der Waals volume, is calculated using the radii of imaginary spheres of atoms and placing them at covalent-bond distances.41 Because of the limit to the packing density of polymer chains, each molecule occupies more space than its molecular volume. This space is called the occupied volume (VO). A polymer in the glassy state has excess volume, known as the free volume (VF), in addition to the occupied volume, as shown in Figure 4A. This free volume allows the mobility of the polymer segments. The free volume is a collective term describing molecular-sized holes (volume elements) present in the specific volume.42 The hole is considered to be similar in size to a segment of a polymer molecule, and the coordinated movements of multiple holes allow the polymer chain mobility.42 The free volume can be represented by mobile holes jumping around in the structure, as shown by open circles in Figure 4B.43 The free volume for various glassy polymers is estimated to be in the range of 11–23% of the total volume.42,44 It is quite a substantial volume. In fact, 11–23% free volume is a massive volume from the perspective of entrapped drug molecules. Above Tg, the equilibrium free volume is temperature-dependent. Below Tg, however, the free volume becomes time-dependent, and this causes aging.12

Figure 4.

(A) The specific volume of a polymer consists of the free volume (VF) and the occupied volume (VO), which is larger than the molecular volume (VM). A portion of the free volume lost on aging is shown by VF,L. (B) The free volume (◯) distributed throughout the occupied volume (●) of a glassy, amorphous polymer (T < Tg) fluctuates slowly, allowing the molecular motion of polymer chains (modified from refs 42 and 43).

The aging process results in a lowering of free volume.16 As shown in Figure 5, this process can lead to a macroscopic volume contraction maintaining the random coil structure (A → B) or accompanying with microscopic heterogeneous fluctuations (A → C). Likely, the macroscopic contraction is not dominant, and free volume diffuses to internal surfaces created by the low-density region, as well as ultimately to the external surface.38 When an amorphous glass is slowly annealed at a temperature (Ta) close to but below Tg, it can undergo physical aging from the nonequilibrium structural state to a more energetically stable state (from state C to D or E in Figure 2I). Thus, the presence of microvoids (C in Figure 5) may not be homogeneous throughout the microparticle. The formed interconnected channels are filled with water when the microparticles are exposed to an aqueous solution (D in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Two potential structural changes caused by physical aging. A random coil polymer structure in the quenched amorphous glass (A) can undergo macroscopic volume contraction while maintaining the overall structure (B) or heterogeneous structural relaxation in the microscopic domains creating microvoids (C), which are then filled with water when exposed to an aqueous solution (D) (modified from ref 16).

The absorption of water into the core of dried PLGA microparticles may occur in a matter of seconds or minutes.45 In addition, the Tg of a PLGA microparticle formulation is close to 37 °C, as is the case with many microparticles made of PLGA 50:50 with low molecular weights. As shown in Figure 3, PLGA microparticles can reach the equilibrium state rapidly in a matter of minutes. It means that the formation of microvoids in Figure 5C can occur in those periods, resulting in the initial burst release. Thus, internally located drug molecules can undoubtedly contribute significantly to the initial burst release. Whether the physical aging increases or decreases the drug release rate, the rate also depends on the water solubility of the drug and the drug–PLGA interactions. Aging may be manifested into a tendency to decrease permeability (of hydrophobic drugs) due to the increased density of polymer chains.46 However, even hydrophobic drugs dissolve in water to a certain extent, and they can be released faster at the very beginning of the release. The release of hydrophilic drugs can certainly be accelerated due to the formation of microvoids. The extent of acceleration depends on the degree of interconnection among microvoids and the porosity formed during the preparation of microparticles.

2.6. The Free Volume and the Initial Burst Release.

Interpreting the drug release profiles has been a challenging problem.47 A typical drug release profile for PLGA-based formulations usually consists of three phases, e.g., burst, lag, and final, erosion phases,35,48 or burst release, near-constant release rate, and rapid release to complete drug exhaustion.49 The exact distinction between the three phases, however, is not apparent. The point here is that there are different phases of drug release, and the mechanism governing each phase may be different. Current theories are based on the assumption that the burst phase occurs due to the dissolution of immediately available drug substance and diffusion through surface-related pores.35 More studies, however, have presented evidence indicating that the burst release is also influenced by the polymer swelling and drug diffusion, in addition to the dissolution of immediately available drug molecules.35,50

In the process of drug release from PLGA microparticles, hydration is the first fundamental step, and the absorbed water initiates the drug release process.28 The role of the absorbed water, however, goes beyond the dissolution of drug molecules. The absorbed water also reduces the Tg of the PLGA matrix. When PLGA (Resomer RG503H, 50:50, 30 kDa) was exposed to water, Tg decreased by about 15 °C within an hour even at room temperature, e.g., 47.7–32.7 °C.29 Similar results were observed with ester end-capped PLGA (Resomer RG503, 50:50, 38 kDa). The fact that the Tg decreases below the body temperature within 1 h (even in 30 min) implies profound changes in the PLGA properties as soon as the drug release process begins. The lowering of Tg accelerates the aging process described in Figure 5. The microscopic channels in the PLGA matrix were already formed during the solvent extraction and drying process. The increase in the microvoids in Figure 5C will enhance water absorption upon exposure to the aqueous solution. As the Washburn equation showed,45 water absorption into PLGA microparticles can occur in a matter of seconds. Thus, hydrophilic drugs tend to be released faster with a major initial burst. Even compressed cylindrical tablets (9 mm diameter × 5 mm height) of poly(DL-lactic acid) (PDLLA, viscosity averaged molecular weights (Mv) of 12.5–241.5 kDa) containing 20% theophylline monohydrate showed immediate water uptake, reaching an equilibrium axial expansion in 30–60 min for molecular weights of 21.7, 41.8, and 136.5 kDa.51 When the tablets were placed in 37 °C water, the Tg was reduced immediately by 10–12 °C.51 When PLGA, including PLA, formulations are introduced to an aqueous solution at 37 °C, the applied stress due to compression for tablets (and solvent removal for microparticles) is removed, resulting in entropy-driven relaxation of compacted PLGA matrices.51 Since most PLGA formulations contain surfactants and residual solvents, the decrease in Tg of the formulations is expected to be large and become closer to 37 °C or even lower, especially for PLGAs of 50:50 and low molecular weights. Thus, it is not surprising to observe the initial burst release of hydrophilic drugs and those that can be released through aqueous channels.

The effect of physical aging on drug release was studied using dexamethasone-loaded PLGA microparticles (Resomer RG503H, 50:50, 25 kDa).52,53 Structural relaxation of the microparticles (Tg of approximately 42 °C) did not alter the dexamethasone release kinetics significantly.52 The drug release profile from microparticles stored at 25 °C under a vacuum for 12 months was not significantly different from the same formulation stored at −20 and 4 °C. A typical triphasic release profile (an initial burst release, a lag phase, and a steady-state zero-order release) did not change, but the release was decreased by only about 6% after Day 25. Another study showed essentially the same result, i.e., decreased by 8% after Day 20.53 This decrease was ascribed to the reduced free volume of the PLGA microparticles incubated at 25 °C. Another study examined the effects of both temperature (25 °C) and moisture level (60% RH) during storage.53 After storing under 60% RH for 12 months, the dexamethasone release from PLGA microparticles increased by more than 5% on Day 1 and 10% in 2 weeks. While there may be small differences observed after 20 days of drug release for microparticles stored at 25 °C for 12 months, there were no differences in the first 20 days. It is understandable because any impact of physical aging may not be significant enough if the storage temperature is more than 18 °C lower than the Tg, as described in eq 1. More importantly, the Tg values of PLGA formulations made of RG503H are close to 25 °C (42–15 °C) after exposure to water. Thus, all of the samples had ample time to undergo structural relaxation (Figure 5C), resulting in the same initial burst release. The minor differences observed in the later stage of drug release indicates that there may be additional reasons for the slight decrease in the observed release. Therefore, it is not surprising to observe no clear relationships between the structural relaxation and the performance of antibody-loaded PLGA microparticles (made of 10% PLGA (Resomer RG505 or RG755 S) in ethyl acetate by a solid/oil/water (S/O/W) emulsion method).54

The ability to predict drug loading and release kinetics from PLGA microparticles is critical in developing various long-acting formulations. PLGA microparticles were prepared with 8 different drugs using 1% PLGA (Resomer RG502H, 50:50) in propylene carbonate with drug loadings of 20%.55 The drug release results indicated that a single parameter could not be correlated to the drug release behavior. Again, it is understandable because the drug release kinetics depend on multiple factors. The shape of microparticles after drying was influenced by the microparticle Tg. When the microparticle Tg increased from 28.6 °C (for ibuprofen) to 51.8 °C (for erythromycin), the microparticle shape changed gradually from shrunken, nonspherical to spherical. All microparticles showed highly wrinkled and porous surface morphology, except the erythromycin microparticles, which exhibited an irregular, highly buckled but a relatively smooth surface.55 The results of the study collectively demonstrated that the drug release kinetics could be explained by considering the octanol–water partition coefficient (i.e., logP), microparticle Tg, and surface morphology. The data were just enough to rationalize the results, but not sufficient enough for prediction of release from microparticles yet to be made.

2.7. Tg of PLGA Microparticles and the Burst Release.

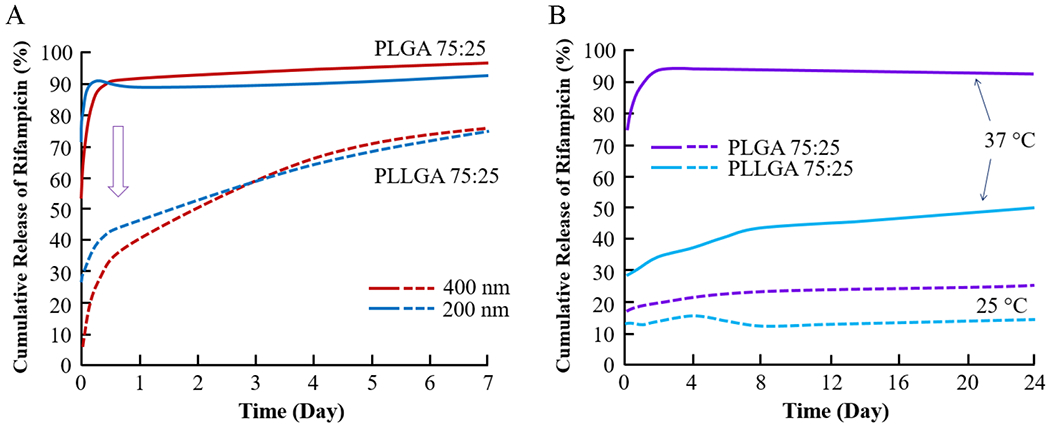

The Tg is known to affect the initial burst release. The extent of the burst release may depend on various factors, including the drug distribution throughout the PLGA microparticles. For the particles prepared similarly, the Tg may be a key factor influencing the burst release. The release of rifampicin from PLGA nanoparticles (with the drug loading of 2.5–5.3 w/w%) was strongly affected by Tg.56 The 400 nm nanoparticles made of PLGA (75:25, 10 kDa) and poly(l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLLGA, 75:25, 10 kDa) released 90% and 40% of rifampicin, respectively, in 24 h (Figure 6A). The Tg of PLLGA polymer was 7 °C higher than that of PLGA polymer, i.e., 47.7 °C vs 40.6 °C. The same formulations, but 200 nm in size, were used to examine the influence of temperature, i.e., the drug release at 37 °C vs 25 °C. The cumulative rifampicin releases from PLGA nanoparticles in the first 24 h were 92% and 25% of the total drug at 37 and 25 °C, respectively (Figure 6B). The release from PLLGA nanoparticles was 50% and 15% at 37 and 25 °C, respectively. The temperature differences between the Tg of PLGA polymer (40.6 °C) and 37 or 25 °C are 3.6 and 15.6 °C, while those of PLLGA (47.7 °C) are 10.7 and 22.7 °C, respectively. The initial burst release depends on the difference between the Tg and the temperature of the drug release. It is important to note that there was only a small difference in rifampicin release from PLGA and PLLGA at 25 °C, a much lower temperature than the Tg of PLGA and PLLGA polymers. This indicates that the time to reach a thermodynamic equilibrium state affects the extent of the initial burst release. As the equilibrium state is reached faster, the PLGA structure changes faster to release more drug.

Figure 6.

Cumulative release of rifampicin from nanoparticles made of PLGA 75:25 and PLLGA 75:25 with 200 and 400 nm at 37 °C (A) and at 25 and 37 °C with 200 nm (B) (modified from ref 56).

The Tg of flurbiprofen-loaded PLGA nanoparticles in suspension decreases steadily from 28.8 °C with 1.7% loading to 19.9 °C with 21% loading.57 The extent of the initial burst release was dependent on Tg. Instant drug release was observed at temperatures above the Tg, while less drug was released at lower temperatures. It is consistent with the results shown in Figure 6B. A higher drug content seems to be able to enhance polymer chain mobility, i.e., plasticization, resulting in a lowered Tg. The shift in Tg suggests that the drug is molecularly dispersed during nanoparticle preparation. The molecular size, structure, and hydrophilicity of the used drug are relevant parameters with crucial influence on Tg of the resulting nanoparticle system.57 This result suggests that the initial burst release will be reduced if the Tg of a PLGA microparticle formulation is above the physiological temperature of 37 °C.57

Another factor affecting the initial burst release, if the Tg values are close, is the molecular weight. Since the polymer molecular weight impacts Tg, it may be difficult to independently vary the two parameters. Yet, different nanoparticles with different molecular weights have shown significantly different burst releases. The nanoparticles made of PLGA 75:25 with 15 kDa (polymer Tg = 42.2 ± 0.1) or 20 kDa (polymer Tg = 42.7 ± 0.1) showed that the initial release in 24 h is 94% and 83%, respectively. While the difference is small, it indicates that the molecular weight is a factor that can influence the drug release, probably by higher entanglement of higher molecular weight PLGA chains.58 The influence of molecular weight was also observed with PLGA 50:50 (Resomer RG502 (8 kDa), 503 (32 kDa), 504 (37 kDa), and 505 (45 kDa). The Tg of dry microparticles was 39–43 °C, and the initial release was 28%, 12%, 4%, and 2%, respectively, as the molecular weight increased.40 The release of the drug from the surface cannot explain the extreme difference, 28% vs 2%.40 Different molecular weights may have different viscosities even at the same weight concentration, affecting the overall porosity of microparticles. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that drug diffusion from the microparticles contributes significantly to the initial burst.

2.8. Structural Reconfiguration of Microparticles after the Initial Burst Release.

The discussion on the initial burst release leads to the next question as to why the drug release rate decreases after the initial burst if the drug can be released through microvoids, i.e., pores and channels.59–61 The in vitro drug release was shown to be dependent on the Tg of the polymers and the porosity of the prepared formulations.62 One common observation in the drug release profiles from PLGA formulations is that the initial burst release is followed by steady-state release, sometimes almost like zero-order release. It cannot be explained by the increased diffusion length alone. Thus, it appears that there is rapid structural reconfiguration, especially at the surface. Since the overall structure of microparticles is still intact right after administration, the only place a rapid transformation occurs may be the surface. Since polymer molecules near the surface have higher mobility, they will undergo rapid rearrangement. The release medium penetrates into the microparticles to act as a plasticizer.63 It results in lowering of the Tg and softening of microparticles, providing a condition for the restructuring of the skin layer. The skin layer becomes denser, and the pores close.59 PLGA (50:50, 6–10 kDa) microparticles prepared in the presence of 0.42% glycerol in the primary dichloromethane (DCM) dispersion resulted in a decrease of Tg from 42.5 to 36.7 °C. When these microparticles were immersed in a phosphate-buffered solution at 37 °C, the porous structure disappeared immediately, resulting in a drastically suppressed initial release.64 The consequence of this change is to form a diffusion-controlled reservoir system, with drug release following zero-order kinetics. Microparticles that undergo structural reconfiguration faster will result in earlier closed pores. Thus, the type of PLGA used to fabricate microparticles, and the resultant density, and Tg of the microparticle, can explain the extent of the initial burst release.

The structural reconfiguration continues after the initial burst release. It means the changes in the microparticle structure, such as pore closing, swelling, and variations in local densities of PLGA chains. Extensive studies on the pore closing phenomenon indicate that the presence of water and temperature greater than Tg are two necessary factors.65–71 Such alterations result in the lag period of drug release or steady-state drug release. Because the PLGA chain density and molecular weight distribution vary throughout the microparticle, the structural reconfiguration will be anisotropic. The extent of structural reconfiguration in the skin (or the surface region of the microparticle) will affect the subsequent drug release kinetics. The pore closing was much more significant at 45 °C. PLGA microparticles loaded with albumin and FITC-dextran were prepared using 70% PLGA (50:50) or 30% glucose–PLGA (50:50, 50 kDa) in DCM.65 The cumulative release after 66 h was 43%, 46%, 15%, and 8% at 4, 25, 37, and 45 °C, respectively. This result can be explained by slow structural relaxation at lower temperatures and faster pore closing at higher temperatures.65

If the change in the drug release kinetics is due to the structural reconfiguration, then a relevant follow-up question is whether PLGA microparticles can be prepared with a minimum free volume and eliminated pores during the manufacturing process. Structural reconfiguration was used to load biomacromolecules without exposing them to organic solvents.66,68 The porous PLGA microparticles were dispersed into a concentrated protein (such as lysozyme, ovalbumin, and tetanus toxoid) solution at temperatures lower than Tg, e.g., 4 or 10 °C, for protein entry through the pores. The pores were healed, i.e., closed, by raising the temperature to higher than Tg, e.g., 38 or 42.5 °C. PLGA microspheres loaded with octreotide acetate were prepared by a double emulsion method using 30% PLGA (50:50, 50 kDa) in DCM. The microparticle morphology changed substantially right after the initial burst release, with the decreased porosity of the skin layer. As the density of the skin increased with negligible surface pores, the skin became a diffusion barrier.59 The formation of a diffusion barrier can easily explain the near zero-order release of the loaded drug during the steady state. The increased release during the steady release occurs if the PLGA polymers started degradation.

3. TERMINAL STERILIZATION

Manufacturing PLGA formulations aseptically following the current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) regulations can produce clinical products. It, however, is not practical for microparticle manufacturing, which involves multiple components, manufacturing processes, and post-treatment steps with their respective associated cost. Terminal sterilization, after manufacturing under CGMP conditions, simplifies the whole process significantly. However, it has its own difficulties. Steam or dry heat sterilization can lead to hydrolysis of PLGA chains and deformation at higher temperatures. Ethylene oxide sterilization at 50–60 °C and 40–50% relative humidity is not suitable for PLGA formulations, and also complete removal of the residual gas is difficult.72 Various PLGA microparticles, however, have been terminally sterilized by either γ-irradiation or β-irradiation (electron-beam or e-beam).

3.1. Ionizing Radiation Sterilization.

Both γ-irradiation and e-beam result in practically the same ionization radiation effects. The dose of 25 kGy (2.5 Mrad) is the accepted sterilization dose for pharmaceutical products. γ-Irradiation sterilization, however, is also known to alter the properties of drug delivery formulations. Irradiation is known to increase the temperature of formulations for a few seconds for e-beam sterilization (typically to 50 °C with polymeric materials) or a few hours for γ-sterilization (typically 30–40 °C).73 The increase in temperature can be managed by processing at a reduced temperature, e.g., −78.5 °C with dry ice. The potential impacts of oxygen and humidity can be eliminated by vacuuming or flushing formulations with inert gas, such as nitrogen or argon. The radical concentrations were reported to be higher as the lactide content of the PLGA increased (e.g., 75:25 > 65:35 > 50:50) for both γ- and β-irradiation. It may be due to the more dominant scission of PLGA chains in the amorphous regions.74 PLGA microparticles treated with e-beam produced only half of the radical content compared to the identical γ-irradiated microparticles.75 The main effect of the radiation on PLGA has been chain scission leading to reduced molecular weight.75,76 The reduction in the PLGA molecular weight may be compensated by increasing the initial, presterile molecular weight. The change to the initial molecular weight of raw PLGA, however, is likely to affect other variables in the manufacturing process, e.g., increased viscosity of polymer solution. This will warrant modification to the established manufacturing process to ensure comparable drug release properties of the final formulation. It could be challenging to adjust the manufacturing process. Therefore, it is vital to examine early during development whether and how terminal sterilization can affect the drug release kinetics of the formulation of interest.

3.2. Impacts of Terminal Sterilization on Drug Release.

The effects of terminal sterilization on drug release kinetics are not clearly understood. The impacts of γ-irradiation or e-beam on drug release properties vary significantly. It is understandable since drug release does not solely depend on pLGA molecular weight but is a function of many factors, including the drug properties and manufacturing processes. The net effect of terminal sterilization on drug release kinetics can be faster, similar (i.e., no significant change), or slower, as listed in Table 3. There are ample examples in the literature, and the effects are not straightforward.

Table 3.

Examples of Ionizing Radiation Sterilization of PLGA Formulations on the Drug Release Kinetics

| drug releaseb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| drug (% loading)a | PLGA L:G ratio, mol wt. (concentration in solvent) | radiation condition and dose | Tg (°C) of formulation | initial burst | steady statec | ref |

| Increased Release | ||||||

| cladribine (4.5%) | 82:18 (DCM, solution-casted film) | γ-irradiation (rt, air)d | (normalized) | t = 24 day | 77 | |

| 0 kGy | 9 μM/mg | 2 μM/mg | ||||

| 15 kGy | 24 μM/mg | 8 μM/mg | ||||

| 20 kGy | 26 μM/mg | 4 μM/mg | ||||

| 25 kGy | 33 μM/mg | 3.8 μM/mg | ||||

| bupivacaine (BU) | 50:50 Resomer RG503, 34 kDa | irradiation (25 °C, air) | (25% BU) | t = 7 day | 78 | |

| (10%, 25%, 40%) | (2% in DCM, spray drying) | 0 kGy | 44.7 ± 0.3 | 11% | 55% | |

| 25 kGy: β-irradiated | 42.1 ± 0.0 | 16% | 79% | |||

| γ-irradiated | 40.6 ± 0.2 | 17% | 85% | |||

| rasagiline mesylate (9%) | 50:50 Resomer RG502 | γ-irradiation (dry ice, air) | t = 7 day | 79 | ||

| (40% in DCM, O/W emulsion) | 0 kGy | 43.3–48.7 | 6% | 54% | ||

| 25 kGy | 41.2 °C | 8% | 80% | |||

| 17β-estradiol (17E) in acetone (7.9%, 18.4%) | 50:50 Resomer RG503, 34 kDa, 75:25 Resomer RG752, 17 kDa (8% in DCM/acetone 7:3, Spray drying) | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C) | (7.9% 17E) | t = 20 day | 80 | |

| 0 kGy | 36.0 | 4% | 25% | |||

| 5.1 kGy | 35.4 | 5% | 31% | |||

| 15.2 kGy | 36.8 | 5% | 39% | |||

| 26.6 kGy | 36.0 | 6% | 50% | |||

| carmustine (BCNU) (4%) | 50:50 Resomer RG502H, 8 kDa (compression molded) | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C, air) | (PLGA only) | t = 4 day | 81 | |

| 0 kGy | 42.2 | 27% | 68% | |||

| 2.5 kGy | 41.5 | 25% | 67% | |||

| 5.0 kGy | 39.7 | 28% | 73% | |||

| 7.5 kGy | 37.6 | 31% | 80% | |||

| 5-fluorouracil (20%) | 50:50 Resomer 506, 104 kDa (11% in DCM, O/W emulsion) | γ-irradiation (rt) | dry (wet) | t = 11 day | ,82 | |

| 0 kGy | 40.7 (29.3) | 25% | 61% | |||

| 19.6 kGy | 33% | 71% | ||||

| 5-fluorouracil (20%) | 50:50 Resomer 506, 104 kDa (11% in DCM, O/W emulsion) | γ-irradiation (rt) | t = 10 day | 83 | ||

| 4 kGy | 28% | 76% | ||||

| 11 and 17 kGy | 29% | 78% | ||||

| 23 and 28 kGy | 30% | 82% | ||||

| 33 kGy | 31% | 85% | ||||

| insulin-like growth factor-1 (7%) | 50:50 Resomer 506, IV 0.8 dL/g (5% in DCM, W/O/W emulsion) | γ-irradiation (rt, air) | t = 14 day | 84 | ||

| 0 kGy | 62.5 | 26% | 60% | |||

| 25 kGy | 49.0 | 36% | 68% | |||

| Similar Release | ||||||

| captopril (6.7–8.1%) | 50:50 Resomer RG502, 16.5 kDa | γ-irradiation | (51.5 kDa) | (51.5 kDa) | (51.5 kDa) | 85 |

| 50:50 Resomer RG503, 40.5 kDa | (−78.5 °C, vacuum) | t = 11 day | ||||

| 50:50 Resomer RG504, 51.5 kDa | 0 kGy | 30 | 34% | 77% | ||

| 50:50 Resomer RG505, 66.0 kDa | 6.9 and 15.0 kGy | 32 and 32 | 31% | 68% | ||

| (10% in DCM, spray drying) | 27.7 kGy | 30 | 24% | 66% | ||

| 34.8 kGy | 32 | 23% | 63% | |||

| indomethacin (17%) | 50:50 Resomer RG503, 34 kDa | γ-irradiation | 2 | t = 12 Day | 86 | |

| (20% in DCM, O/W) | (rt and −78.5 °C) | |||||

| 0 kGy | 40.3 ± 0.2 | 20% | 63% | |||

| 25 kGy: rt | 35.3 ± 0.5 | 27% | 72% | |||

| −78.5 °C | 40.4 ± 0.6 | 20% | 62% | |||

| naproxen (NX), diclofenac (DF) (10%) | 50:50 Medisorb, 34 kDa and 88 kDa | γ-irradiation (rt, vacuum) | (88 kDa) | (88 kDa) | t = 2.5 day | 87 |

| (4.6% in methanol:DCM 0.3:1, O/W emulsion) | NX DF | NX DF | NX DF | |||

| 0 kGy | 41.2, 41.2 | 27%, 36% | 70%, 56% | |||

| 5 kGy | 41.3, 42.2 | 26%, 35% | 70%, 57% | |||

| 15 kGy | 41.7, 43.8 | 27%, 35% | 74%, 63% | |||

| 25 kGy | 41.8, 44.4 | 27%, 35% | 74%, 76% | |||

| aciclovir (16%) | 50:50 Resomer RG502, 15 kDa (40% in DCM, O/W emulsion) | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C, air) | t = 35 day | 88 | ||

| 0 kGy | 44.7 | 6% | 55% | |||

| 25 kGy | 46.5 | 7% | 56% | |||

| thienorphine (10%) | 75:25, 15 kDa (20% in DCM, O/W emulsion) | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C) | t = 10 day | 89 | ||

| 0 kGy | 12% | 60% | ||||

| 10 kGy | 12% | 60% | ||||

| 15 kGy | 10% | 60% | ||||

| 25 kGy | 13% | 60% | ||||

| gentamicin | 1:1 mixture of | t = 3 day | 90 | |||

| 50:50 Resomer RG502H | 0.0 kGy | 47 | 10% | 63% | ||

| 50:50 Resomer RG503 | 25.3 kGy (β-irradiation) | 41 | 12% | 68% | ||

| (10% in DCM, W/O/W emulsion) | 28.9 kGy (γ-irradiation) | 43 | 33% | 67% | ||

| malarial antigen (<0.01%) | 50:50 Resomer RG506, 103 kDa | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C) | t = 50 day, t =90 day | 91 | ||

| 75:25 Resomer RG756, 92 kDa | (50:50), (75:25) | (50:50), (75:25) | (50:50), (75:25) | |||

| (5% in DCM, W/O/W) | 0 kGy | 55.0, 59.2 | 23%, 42% | 70%, 60% | ||

| 25 kGy | 53.3, 56.0 | 24%, 42% | 83%, 59% | |||

| vancomycin (10%) | poly(ε-caprolactone) 10, 42.5, 70–90 kDa (20% in DCM, W/O/W emulsion) | γ-irradiation (25 °C, 65% relative humidity) | (42.5), (70–90) | (42.5), (70–90) |

t = 10 day t = 30 day (42.5), (70–90) |

92 |

| 0 kGy | 56.0, 56.9 | 60%, 20% | 93% 50% | |||

| 25 kGy | 56.0, 56.4 | 54%, 20% | 81% 54% | |||

| vancomycin (16%) | 50:50 Resomer RG503, IV 0.4 dL/g (compressed, sintered at 65 °C for 30 min) | γ-irradiation | (release rate) | t = 10 day | 93 | |

| 0 kGy | 44.1 | 3.85 μg/mL | 3.08 μg/mL | |||

| 15 kGy | 42.7 | 3.85 μg/mL | 3.30 μg/mL | |||

| 20 kGy | 41.7 | 3.85 μg/mL | 2.48 μg/mL | |||

| 25 kGy | 44.4 | 4.30 μg/mL | 2.90 μg/mL | |||

| 30 kGy | 42.7 | 2.48 μg/mL | 1.60 μg/mL | |||

| 35 kGy | 42.4 | 2.48 μg/mL | 1.90 μg/mL | |||

| ganciclovir (9%) | 50:50, 34 kDa | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C, air) | t = 14 day | 94 | ||

| (30% in acetone, O/O emulsion) | 0 kGy | 12% | 58% | |||

| 25 kGy | 8% | 58% | ||||

| Decreased Release | ||||||

| growth hormone (10%) | 9:1 ratio of 50:50 Resomer RG502H and 100:0 Resomer R 202H, IV 0.16–0.24 dL/g | γ-irradiation (rt, air) | t = 6 day | 95 | ||

| 0 kGy | 46% | 87% | ||||

| (supercritical CO2 processing) | 25 kGy | 22% | 62% | |||

| 100 kGy | 25% | 40% | ||||

| neurotrophic factor (<0.01%) | 50:50 Resomer RG503, 35 kDa | γ-irradiation (−78.5 °C and rt) | (W/O/W) (−78.5 °C) (rt) | 96 | ||

| (20% in DCM, W/O/W and S/O/W) | 0 kGy | 16.1 ng/mg | 292.4 (pg/(mg day)) | |||

| 25 kGy | 5.5, 2.4 | 33.5, 10.0 | ||||

% Drug loading = 100((weightdrug)/(weightdrug + weightPLGA)).

Drug release kinetics before and after sterilization was examined by comparing the % cumulative drug release or the amount released.

The steady state was chosen at 50% of the drug release time reaching the cumulative plateau release.

Room temperature in the air.

Many PLGA formulations have shown increased drug release after sterilization by γ-radiation or e-beam when the percent cumulative release data were compared. The release of cladribine from a solution-casted film increased approximately 2-fold during the same period of 48 days after γ-irradiation to 25 kGy at room temperature under atmospheric conditions.77 The bupivacaine release rates from PLGA microparticles increased by 50% after sterilization, but they were less affected by e-beam than γ-radiation.78 A similar extent of faster release was also observed with rasagiline mesylate.79 17β-Estradiol-loaded microparticles were prepared by spray drying the mixture of the drug and PLGA, followed by γ-irradiation at −78.5 °C using dry ice. The in vitro drug release was accelerated in a dose-dependent manner at 5.1–26.6 kGy doses.80 The drug releases in the first 7 days were comparable, but the time to 50% drug release was shortened from 28.5 days (control) to 25 days (5.1 kGy), 22 days (15.2 kGy), and 19 days (26.6 kGy) after γ-irradiation. The faster release was attributed to faster erosion of PLGA having lower molecular weights. The release kinetics of Carmustine (bis-chloroethyl nitrosourea, BCNU) from a compression-molded wafer formulation81 and 5-fluorouracil from microparticles82,83 also showed a 10–15% increase. Even a PLGA formulation loaded with a protein, such as insulin-like growth factor-1, was successfully sterilized with an only moderate increase in all phases of the release kinetics.84 These examples show that the drug release rate can increase after sterilization.

Many formulations have also shown that the release kinetics does not change significantly and varies within a 10% range in the percent cumulative release profiles. They include formulations of captopril,85 indomethacin,86 clonazepam,97 naproxen and diclofenac,87 doxorubicin,98 aciclovir,88 thienorphine,89 gentamicin,90 malarial antigen,91 and vancomycin.92,93 Some formulations have even shown decreased drug release kinetics. The reduced release kinetics may range from an insignificant (e.g., ganciclovir94) to a substantial reduction in release kinetics (e.g., growth hormone95 and neurotrophic factor96). Many formulations show only slight changes in the drug release kinetics, as long as the irradiation was limited to 25 kGy or less.85,86,90,98,99 The incomplete release may be due to drug degradation, drug removal, or an incomplete release from formulations for a variety of reasons. The release of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor from PLGA microparticles was reduced more than 2-fold after γ-irradiation of 25 kGy.96 The overall release pattern (initial burst, slow release period, and the second burst) remained the same, but the extent of the initial and the second burst releases were significantly reduced by γ-irradiation. The decreased release kinetics of hydrophilic drugs from microparticles may be attributable to the disturbed water channels by γ-irradiation, as suggested for captopril.85

The effects of irradiation sterilization on drug release kinetics vary, and it is likely due to different impacts of irradiation on the overall structure of PLGA formulations, rather than the PLGA chain scission alone. Compressed sheets of PLGA (85:15, Corbion, 1.7 g/cm3) in a dumbbell shape were γ-irradiated to 40 kGy at 25 °C and −80 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere.76 γ-Irradiation caused chain scission (which was not affected by the irradiation temperature), and thus, a reduction in Tg. The 40 kGy γ-irradiation, however, did not affect the mechanical strength, indicating γ-sterilization does not affect the structural properties. The solvent-casted PLGA film (85:15, Resomer, 2% in chloroform) showed a 14% decrease in drug release after 40 kGy exposure.100 Sterilization by e-beam (40 kGy) or γ-radiation (20 and 30 kGy) also did not alter the fracture force of dissolving microneedles composed of hyaluronic acid (39 kDa), even though the molecular weight was reduced.101 It appears that the mechanical strength is less affected by chain scissions occurring during the radiation sterilization. This observation can explain, in part, unpredictable, devious effects of γ-sterilization on drug release kinetics. The drug release kinetics do not solely depend on the PLGA molecular weight, and many other factors contribute to the overall drug release kinetics. In addition, terminal sterilization is performed on a polymeric matrix in the glassy or crystalline state, with limited molecular mobility. In this situation, a decrease in molecular weight by irradiation may not change the density of microparticles significantly, even after exposure to the aqueous solution, at least in the early stage of the exposure. As the drug release continues, water is absorbed into the microparticles and causes PLGA chains to unentangle, leading to the reconfiguration of the microparticle structure. In this process, the reduced molecular weights by irradiation increase the chain mobility for drug diffusion.83 At the same time, a competing phenomenon may be in action. The shorter PLGA chains, having better mobility, can align themselves and pack more easily to form a crystalline phase.102 An increased degree of crystallinity in PLGA by chain scission may delay the dissociation of the chains for swelling. Simultaneously, irradiation at −80 °C may provide a cage effect, which reduces the number of effective chain scissions due to free radicals recombining polymer chains nearby.74,102,103 The compactness, or the density of the PLGA matrix, may have a significant impact on the overall drug release kinetics. Thus, the initial PLGA concentration in the organic solvent used to make seed emulsions and the manufacturing process may play more important roles than reducing the PLGA molecular weight.

3.3. Ionizing Radiation and Tg.

γ-Irradiation of PLGA microparticles does not significantly change the Tg of PLGA microparticles69,104 and the initial drug release rate.105,106 While the impact of γ-irradiation may not be noticeable in the beginning, its impact may manifest at later times. Since γ-irradiation reduces the molecular weight, it can affect the PLGA properties, and thus, drug release.107 As microparticles undergo structural reconfiguration of PLGA chains during water absorption and swelling, altered drug release kinetics may become readily apparent and significant. The lower molecular weight may lead to localized reorientation, leading to an additional effective channel to release free volume frozen in the microparticles.14 This structural relaxation induced by γ-irradiation is different from physical aging (shown in Figure 5) that occurs with native molecular weight. It is suggested that γ-irradiation can achieve a more thermodynamically favorable state in a short period, days vs months, at temperatures much lower than Tg.14 Thus, the drug release kinetics may not be affected initially by γ-irradiation, but it may be when structural reconfiguration begins.

4. A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON DRUG RELEASE FROM PLGA MICROPARTICLES

Understanding drug release from PLGA microparticles is essential for finding ways to control the composition and manufacturing process to obtain formulations with consistent, reproducible properties, and more importantly, acquire an ability to design formulations with predetermined drug release kinetics. Many modeling studies have been performed, and they are excellent in curve fitting the data and providing plausible explanations on the drug release mechanisms. The limitation of the modeling approach is that it does not provide a way to design the formulation with specific control over the drug release kinetics.

The analysis of the impact of Tg on drug release highlights that the Tg of a PLGA formulation can explain most of the drug release characteristics. The importance of this is that it allows the control of the drug release kinetics by manipulating the parameters influencing the Tg of a PLGA formulation. As shown in Figure 1, many factors can affect the Tg of PLGA formulations, including the drug’s physicochemical properties, PLGA type, residual solvent(s), drying rate, and post-treatment. Understanding the change in drug release kinetics in terms of the altered Tg of the final formulation allows the rational design of PLGA formulations having desired drug release kinetics. The drug itself can lower the Tg through its plasticizing effect, resulting from its interactions with PLGA polymers depending on the polymer properties.108–110 Some drugs, such as leuprorelin acetate, can have an antiplaticizing effect to increase the Tg.33 Thus, the effect of Tg of a PLGA formulation of a particular drug may not be extended to other drugs. In addition, the Tg may be affected by residual solvents8 and other factors described in Figure 1. Hopefully, a more thorough understanding of the factors controlling the drug release can be identified so that formulations with specific drug release properties can be tailor-made.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant nos. 75F40119C10096 and HHSF223201610091C from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Center for Drug Evaluation Research/Office of Generic Drugs, UG3 DA048774 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the Showalter Research Trust Fund. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the FDA or NIDA.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c01089

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Kinam Park, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering and College of Pharmacy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, United States; Akina, Inc., West Lafayette, Indiana 47906, United States.

Andrew Otte, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, United States.

Farrokh Sharifi, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, United States.

John Garner, Akina, Inc., West Lafayette, Indiana 47906, United States.

Sarah Skidmore, Akina, Inc., West Lafayette, Indiana 47906, United States.

Haesun Park, Akina, Inc., West Lafayette, Indiana 47906, United States.

Young Kuk Jhon, Office of Pharmaceutical Quality, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Maryland 20993, United States.

Bin Qin, Office of Generic Drugs, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Maryland 20993, United States.

Yan Wang, Office of Generic Drugs, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Maryland 20993, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Zhang C; Yang L; Wan F; Bera H; Cun D; Rantanen J; Yang M Quality by design thinking in the development of long-acting injectable PLGA/PLA-based microspheres for peptide and protein drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm 2020, 585, 119441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Allison SD Effect of structural relaxation on the preparation and drug release behavior of PLGA microparticle drug delivery system. J. Pharm. Sci 2008, 97, 2022–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Fredenberg S; Wahlgren M; Reslow M; Axelsson A The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—A review. Int. J. Pharm 2011, 415 (1–2), 34–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Park K; Otte A; Sharifi F; Garner J; Skidmore S; Park H; Jhon YK; Qin B; Wang Y Formulation composition, manufacturing process, and characterization of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles. J. Controlled Release 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhang X; Hu H; Guo M Relaxation of a hydrophilic polymer induced by moisture desorption through the glass transition. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2015, 17 (5), 3186–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Angell CA Glass transition. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2004; pp 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gray LAG; Roth CB Stability of polymer glasses vitrified under stress. Soft Matter 2014, 10 (10), 1572–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Vay K; Frieß W; Scheler S A detailed view of microparticle formation by in-process monitoring of the glass transition temperature. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2012, 81 (2), 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fu X; Ping Q; Gao Y Effects of formulation factors on encapsulation efficiency and release behaviour in vitro of huperzine A-PLGA microspheres. J. Microencapsulation 2005, 22 (7), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Brunacci A; Cowie JMG; Ferguson R; McEwen IJ Enthalpy relaxation in glassy polystyrenes: 1. Polymer 1997, 38 (4), 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bouissou C; Rouse JJ; Price R; van der Walle CF The influence of surfactant on PLGA microsphere glass transition and water sorption: Remodeling the surface morphology to attenuate the burst release. Pharm. Res 2006, 23 (6), 1295–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Struik LCE Physical Aging in Amorphous Polymers and Other Materials; Elsevier: New York, 1978; p 229. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Perez-De Eulate NG; Cangialosi D The very long-term physical aging of glassy polymers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2018, 20 (18), 12356–12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Shpotyuk O; Golovchak R; Kozdras A Physical ageing of chalcogenide glasses. In Chalcogenide Glasses; Adam J-L, Zhang X, Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2014; pp 209–264. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Priestley RD; Ellison CJ; Broadbelt LJ; Torkelson JM Structural relaxation of polymer glasses at surfaces, interfaces, and in between. Science 2005, 309 (5733), 456–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yoshioka T; Kawazoe N; Tateishi T; Chen G Effects of structural change induced by physical aging on the biodegradation behavior of PLGA films at physiological temperature. Macromol. Mater. Eng 2011, 296 (11), 1028–1034. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hutchinson JM Physical aging of polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci 1995, 20 (4), 703–760. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Alves GMA; Goswami SB; Mansano RD; Boisen A Using microcantilever sensors to measure poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) plasticization by moisture uptake. Polym. Test 2018, 65, 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Moynihan CT; Easteal AJ; Wilder J; Tucker J Dependence of the glass transition temperature on heating and cooling rate. J. Phys. Chem 1974, 78 (26), 2673–2677. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Murphy TM; Langhe DS; Ponting M; Baer E; Freeman BD; Paul DR Enthalpy recovery and structural relaxation in layered glassy polymer films. Polymer 2012, 53 (18), 4002–4009. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Turek A; Borecka A; Janeczek H; Sobota M; Kasperczyk J Formulation of delivery systems with risperidone based on biodegradable terpolymers. Int. J. Pharm 2018, 548 (1), 159–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Rudin A; Choi P Mechanical properties of polymer solids and liquids. In The Elements of Polymer Science & Engineering, 3rd ed.; Rudin A, Choi P, Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, 2013; Chapter 4, pp 149–229. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lyons SL; Ramstack JM; Wright SG Preparation of microparticles having a selected release profile. US 6,194,006, 2001.

- (24).Lyons SL; Ramstack JM; Wright SG Preparation of microparticles having a selected release profile. US 6,379,703, 2002.

- (25).Lyons SL; Ramstack JM; Wright SG Preparation of microparticles having a selected release profile. US 6,596,316, 2003.

- (26).Shmool TA; Zeitler JA Insights into the structural dynamics of poly lactic-co-glycolic acid at terahertz frequencies. Polym. Chem 2019, 10 (3), 351–361. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rouse JJ; Mohamed F; van der Walle CF Physical ageing and thermal analysis of PLGA microspheres encapsulating protein or DNA. Int. J. Pharm 2007, 339 (1), 112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Blasi P; D’Souza SS; Selmin F; DeLuca PP Plasticizing effect of water on poly(lactide-co-glycolide). J. Controlled Release 2005, 108 (1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).D’Souza S; Dorati R; DeLuca PP Effect of hydration on physicochemical properties of end-capped PLGA. Adv. Biomat 2014, 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Varga N; Hornok V; Janovák L; Dékány I; Csapó E The effect of synthesis conditions and tunable hydrophilicity on the drug encapsulation capability of PLA and PLGA nanoparticles. Colloids Surf., B 2019, 176, 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Rowe RC; Sheskey P; Quinn M Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 6th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press, 2009; p 888. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Prudic A; Lesniak A-K; Ji Y; Sadowski G Thermodynamic phase behaviour of indomethacin/PLGA formulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2015, 93, 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Okada H; Doken Y; Ogawa Y; Toguchi H Preparation of three-month depot injectable microspheres of leuprorelin acetate using biodegradable polymers. Pharm. Res 1994, 11 (8), 1143–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Sigma-Millipore. RESOMER® biodegradable polymers for medical device applications research. https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/technical-documents/articles/materials-science/polymer-science/Resomer.html (2020).

- (35).Tomic I; Mueller-Zsigmondy M; Vidis-Millward A; Cardot J-M In vivo release of peptide-loaded PLGA microspheres assessed through deconvolution coupled with mechanistic approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2018, 125, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rowe BW; Freeman BD; Paul DR Physical aging of ultrathin glassy polymer films tracked by gas permeability. Polymer 2009, 50 (23), 5565–5575. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rowe BW; Freeman BD; Paul DR Physical aging of membranes for gas separations. In Membrane Engineering for the Treatment of Gases: Vol. 1: Gas-separation Problems with Membranes; Drioli E, Barbieri G, Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2011; Vol. 1, Chapter 3, pp 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Priestley RD Physical aging of confined glasses. Soft Matter 2009, 5 (5), 919–926. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Rothstein SN; Federspiel WJ; Little SR A simple model framework for the prediction of controlled release from bulk eroding polymer matrices. J. Mater. Chem 2008, 18 (16), 1873–1880. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Mylonaki I; Allémann E; Delie F; Jordan O Imaging the porous structure in the core of degrading PLGA microparticles: The effect of molecular weight. J. Controlled Release 2018, 286, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Moldoveanu SC; David V; Moldoveanu SC; David V Solutes in HPLC. Essentials in Modern HPLC Separations 2013, 449–464. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Budd PM; McKeown NB; Fritsch D Free volume and intrinsic microporosity in polymers. J. Mater. Chem 2005, 15 (20), 1977–1986. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gedde UW Polymer Physics 1999, 298. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Thran A; Kroll G; Faupel F Correlation between fractional free volume and diffusivity of gas molecules in glassy polymers. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys 1999, 37 (23), 3344–3358. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Park K; Skidmore S; Hadar J; Garner J; Park H; Otte A; Soh BK; Yoon G; Yu D; Yun Y; Lee BK; Jiang XJ; Wang Y Injectable, ing PLGA formulations: Analyzing PLGA and understanding microparticle formation. J. Controlled Release 2019, 304, 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Horn NR; Paul DR Carbon dioxide plasticization and conditioning effects in thick vs. thin glassy polymer films. Polymer 2011, 52 (7), 1619–1627. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Rothstein SN; Kay JE; Schopfer FJ; Freeman BA; Little SR A retrospective mathematical analysis of controlled release design and experimentation. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9 (11), 3003–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Rothstein SN; Little SR A “tool box” for rational design of degradable controlled release formulations. J. Mater. Chem 2011, 21 (1), 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Tamani F; Bassand C; Hamoudi MC; Danede F; Willart JF; Siepmann F; Siepmann J Mechanistic explanation of the (up to) 3 release phases of PLGA microparticles: Diprophylline dispersions. Int. J. Pharm 2019, 572, 118819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Gu B; Sun X; Papadimitrakopoulos F; Burgess DJ Seeing is believing, PLGA microsphere degradation revealed in PLGA microsphere/PVA hydrogel composites. J. Controlled Release 2016, 228, 170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Steendam R; van Steenbergen MJ; Hennink WE; Frijlink HW; Lerk CF Effect of molecular weight and glass transition on relaxation and release behaviour of poly(DL-lactic acid) tablets. J. Controlled Release 2001, 70 (1–2), 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Rawat A; Burgess DJ Effect of physical ageing on the performance of dexamethasone loaded PLGA microspheres. Int. J. Pharm 2011, 415 (1–2), 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Wang Y; Burgess DJ Influence of storage temperature and moisture on the performance of microsphere/hydrogel composites. Int. J. Pharm 2013, 454 (1), 310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Marquette S; Peerboom C; Yates A; Denis L; Langer I; Amighi K; Goole J Stability study of full-length antibody (anti-TNF alpha) loaded PLGA microspheres. Int. J. Pharm 2014, 470 (1), 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Grizić D; Lamprecht A Predictability of drug encapsulation and release from propylene carbonate/PLGA microparticles. Int. J. Pharm 2020, 586, 119601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Takeuchi I; Tomoda K; Hamano A; Makino K Effects of physicochemical properties of poly (lactide-co-glycolide) on drug release behavior of hydrophobic drug-loaded nanoparticles. Colloids Surf., A 2017, 520, 771–778. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Lappe S; Mulac D; Langer K Polymeric nanoparticles – Influence of the glass transition temperature on drug release. Int. J. Pharm 2017, 517 (1), 338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Takeuchi I; Yamaguchi S; Goto S; Makino K Drug release behavior of hydrophobic drug-loaded poly (lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles: Effects of glass transition temperature. Colloids Surf. A 2017, 529, 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Wang J; Wang BM; Schwendeman SP Characterization of the initial burst release of a model peptide from poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. J. Controlled Release 2002, 82 (2), 289–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Elkharraz K; Ahmed AR; Dashevsky A; Bodmeier R Encapsulation of water-soluble drugs by an o/o/o-solvent extraction microencapsulation method. Int. J. Pharm 2011, 409 (1–2), 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Wright SG; Christensen T; Yeoh T; Rickey ME; Hotz JM; Kumar R; Costantino HR Polymer-based sustained release device. US8,877,252, 2014.

- (62).Kohno M; Andhariya JV; Wan B; Bao Q; Rothstein S; Hezel M; Wang Y; Burgess DJ The effect of PLGA molecular weight differences on risperidone release from microspheres. Int. J. Pharm 2020, 582, 119339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Riaz Ahmed A; Ciper M; Bodmeier R Reduction in burst release from poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles by solvent treatment. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery 2010, 7, 759–764. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Yamaguchi Y; Takenaga M; Kitagawa A; Ogawa Y; Mizushima Y; Igarashi R Insulin-loaded biodegradable PLGA microcapsules: initial burst release controlled by hydrophilic additives. J. Controlled Release 2002, 81 (3), 235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Kang J; Schwendeman SP Pore closing and opening in biodegradable polymers and their effect on the controlled release of proteins. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2007, 4 (1), 104–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Reinhold SE; Desai K-GH; Zhang L; Olsen KF; Schwendeman SP Self-healing microencapsulation of biomacromolecules without organic solvents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51 (43), 10800–10803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Reinhold SE; Schwendeman SP Effect of polymer porosity on aqueous self-healing encapsulation of proteins in PLGA microspheres. Macromol. Biosci 2013, 13 (12), 1700–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Desai K-GH; Schwendeman SP Active self-healing encapsulation of vaccine antigens in PLGA microspheres. J. Controlled Release 2013, 165 (1), 62–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Desai K-GH; Kadous S; Schwendeman SP Gamma irradiation of active self-healing PLGA microspheres for efficient aqueous encapsulation of vaccine antigens. Pharm. Res 2013, 30 (7), 1768–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Mazzara JM; Balagna MA; Thouless MD; Schwendeman SP Healing kinetics of microneedle-formed pores in PLGA films. J. Controlled Release 2013, 171 (2), 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Huang J; Mazzara JM; Schwendeman SP; Thouless MD Self-healing of pores in PLGAs. J. Controlled Release 2015, 206, 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Rogers WJ Sterilisation techniques for polymers. Sterilisation of Biomaterials and Medical Devices 2012, 151–211. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Lambert B; Martin J Sterilization of Implants and Devices. Biomaterials Science 2013, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Loo SCJ; Ooi CP; Boey YCF Radiation effects on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and poly(l-lactide) (PLLA). Polym. Degrad. Stab 2004, 83 (2), 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Bushell JA; Claybourn M; Williams HE; Murphy DM An EPR and ENDOR study of γ- and β-radiation sterilization in poly (lactide-co-glycolide) polymers and microspheres. J. Controlled Release 2005, 110 (1), 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Davison L; Themistou E; Buchanan F; Cunningham E Low temperature gamma sterilization of a bioresorbable polymer, PLGA. Radiat. Phys. Chem 2018, 143, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- (77).Kryczka T; Marciniec B; Popielarz-Brzezinska M; Bero M; Kasperczyk J; Dobrzyński P; Kazimierczuk Z; Grieb P Effect of gamma-irradiation on cladribine and cladribine-containing biodegradable copolymers. J. Controlled Release 2003, 89 (3), 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Montanari L; Cilurzo F; Selmin F; Conti B; Genta I; Poletti G; Orsini F; Valvo L Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres containing bupivacaine: comparison between gamma and beta irradiation effects. J. Controlled Release 2003, 90 (3), 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).FERNANDEZ M; BARCIA E; NEGRO S Effect of gamma-irradiation on biodegradable microspheres loaded with rasagiline mesylate. J. Chil. Chem. Soc 2016, 61, 3177–3180. [Google Scholar]

- (80).Mohr D; Wolff M; Kissel T Gamma irradiation for terminal sterilization of 17β-estradiol loaded poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles. J. Controlled Release 1999, 61 (1), 203–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Lee JS; Chae GS; Khang G; Kim MS; Cho SH; Lee HB The effect of gamma irradiation on PLGA and release behavior of BCNU from PLGA wafer. Macromol. Res 2003, 11 (5), 352–356. [Google Scholar]

- (82).Faisant N; Siepmann J; Benoit JP PLGA-based microparticles: elucidation of mechanisms and a new, simple mathematical model quantifying drug release. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 2002, 15 (4), 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Faisant N; Siepmann J; Oury P; Laffineur V; Bruna E; Haffner J; Benoit JP The effect of gamma-irradiation on drug release from bioerodible microparticles: a quantitative treatment. Int. J. Pharm 2002, 242 (1), 281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Carrascosa C; Espejo L; Torrado S; Torrado JJ Effect of r-sterilization process on PLGA microspheres loaded with insulin-like growth factor - I (IGF-I). J. Biomater. Appl 2003, 18 (2), 95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Volland C; Wolff M; Kissel T The influence of terminal gamma-sterilization on captopril containing poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. J. Controlled Release 1994, 31 (3), 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- (86).Fernández-Carballido A; Puebla P; Herrero-Vanrell R; Pastoriza P Radiosterilisation of indomethacin PLGA/PEG-derivative microspheres: Protective effects of low temperature during gamma-irradiation. Int. J. Pharm 2006, 313 (1), 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Çalış S; Bozdağ S; Kaş HS; Tunçay M; HIncal AA Influence of irradiation sterilization on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres containing anti-inflammatory drugs. Farmaco 2002, 57 (1), 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).MartInez-Sancho C; Herrero-Vanrell R.ıo; Negro S.ıa Study of gamma-irradiation effects on aciclovir poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic) acid microspheres for intravitreal administration. J. Controlled Release 2004, 99 (1), 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Yang Y; Gao Y; Mei X Effects of gamma-irradiation on PLGA microspheres loaded with thienorphine. Die Pharmazie 2011, 66 (9), 694–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Friess W; Schlapp M Sterilization of gentamicin containing collagen/PLGA microparticle composites. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2006, 63 (2), 176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Igartua M; Hernández RM; Rosas JE; Patarroyo ME; Pedraz JL γ-Irradiation effects on biopharmaceutical properties of PLGA microspheres loaded with SPf66 synthetic vaccine. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2008, 69 (2), 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]