Abstract

The RecJ protein of Escherichia coli plays an important role in a number of DNA repair and recombination pathways. RecJ catalyzes processive degradation of single-stranded DNA in a 5′-to-3′ direction. Sequences highly related to those encoding RecJ can be found in most of the eubacterial genomes sequenced to date. From alignment of these sequences, seven conserved motifs are apparent. At least five of these motifs are shared among a large family of proteins in eubacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea, including the PPX1 polyphosphatase of yeast and Drosophila Prune. Archaeal genomes are particularly rich in such sequences, but it has not been clear whether any of the encoded proteins play a functional role similar to that of RecJ exonuclease. We have investigated three such proteins from Methanococcus jannaschii with the strongest overall sequence similarity to E. coli RecJ. Two of the genes, MJ0977 and MJ0831, partially complement a recJ mutant phenotype in E. coli. The expression of MJ0977 in E. coli resulted in high levels of a thermostable single-stranded DNase activity with properties similar to those of RecJ exonuclease. Despite overall weak sequence similarity between the MJ0977 product and RecJ, these nucleases are likely to have similar biological functions.

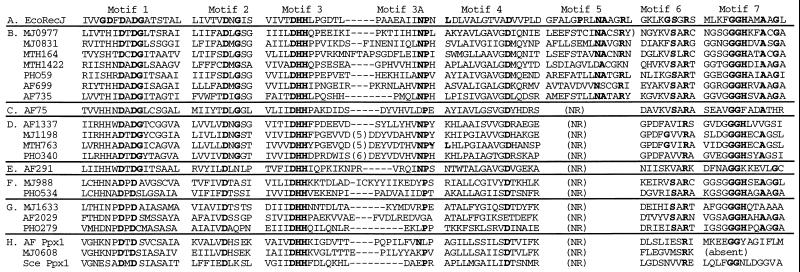

The RecJ exonuclease of Escherichia coli is a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-specific exonuclease that plays a role in DNA repair, recombination, and mutation avoidance (4, 6, 8, 9, 11). A comparison of the available sequenced genomes shows that RecJ is ubiquitous throughout the eubacteria. Sequences with a strong similarity to E. coli RecJ are found in at least nine bacterial divisions, indicating an ancient origin and important biological function for RecJ. Alignment of sequences from 11 eubacterial genera with strong similarity to RecJ has revealed seven conserved motifs among the eubacterial RecJ proteins (10) (Fig. 1). Mutational analysis of amino acids within six of these motifs in the E. coli RecJ protein (motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7) confirmed that these residues are essential for exonuclease activity in vitro and genetic function in vivo (10). Residues within these motifs are good candidates for interactions with the phosphates of the substrate DNA, or with Mg2+ ions, which are cofactors required for RecJ-mediated hydrolysis of DNA (9).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of RecJ motifs among archaeal proteins and PPX1 of S. cerevisiae. MJ, AF, MTH, and PHO prefixes indicate proteins of the archaea M. jannaschii, A. fulgidus, M. thermoautotrophicum, and P. horikoshii, respectively. Eco, E. coli sequence; Sce, S. cerevisiae sequence. NR, the motif is not recognizable within the sequence alignments. Each member of the defined groups has very strong sequence similarity to other members of the group, with E values in pairwise BLASTP alignments of <10−25. (A) Conserved motifs from the E. coli RecJ sequence, with invariant residues among the eubacterial RecJ-related sequences (11) shown in bold. (B) Motifs from group B archaeal sequences with strongest similarity to RecJ. (C) AF0075 archaeal sequence with somewhat weaker similarity to RecJ and similarity to group B. (D) Archaeal RecJ-related sequences with both RecJ motifs and an N-terminal DnaJ domain. (E) AF0291, an outlying archaeal sequence with no strong homology to any of the other groups. (F) Archaeal sequences with similarity to group G. (G) Sequences with similarity to group F. (H) PPX1 of S. cerevisiae and related sequences from archaea.

The genomes of archaea are especially rich in sequences carrying RecJ motifs: Methanococcus jannaschii has six, Archaeoglobus fulgidus has seven, and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum and Pyrococcus horikoshii each have three. Each of these archaeal hypothetical proteins contains at least five of the seven motifs that are conserved among eubacterial RecJ proteins (Fig. 1). Although overall sequence similarity between these proteins and eubacterial RecJ is limited, the presence of the RecJ motifs strongly suggests that these proteins are related to RecJ and raises the possibility that they possess exonuclease activity.

The conserved motifs in RecJ define a large family of proteins in eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (2, 10). Although the biochemical properties of this group, for the most part, have not been established, it includes two proteins that have been characterized extensively: the ssDNA-specific RecJ exonuclease of E. coli (9) and the PPX1 polyphosphatase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (14, 15). Although RecJ and PPX1 have very little amino acid sequence similarity outside the conserved motifs, both have phosphoesterase activity, albeit on very different biological substrates. Although the presence of the RecJ motifs implicates phosphoesterase activity, it is difficult at present to assign phosphatase or exonuclease activity to individual members of this family. We have therefore chosen to examine the three open reading frames from M. jannaschii with strongest similarity to the sequences encoding eubacterial RecJ. We have tested these genes for genetic complementation of a UV-sensitive phenotype conferred by a recJ mutation in E. coli and for expression of nuclease activity on DNA. Two of the genes, MJ0977 and MJ0831, do indeed show partial genetic complementation, indicating that they likely share function with RecJ exonuclease. We also demonstrate that one of these genes, MJ0977, encodes a thermostable ssDNA nuclease activity with properties similar to those of E. coli RecJ exonuclease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Database searches.

The gapped BLASTP and PSI-BLAST programs (1) were used to generate sequence alignments by use of the website provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www/ncbi/nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). In all cases, the BLOSUM62 matrix was used, with gap penalties of 11 (open) and 1 (per residue extension), with a lambda ratio of 0.85, and with the sequence filter off.

Plasmids.

The following primers were used to amplify three recJ-related sequences from M. jannaschii genomic DNA by use of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) under conditions described by the manufacturer: 5′ TAATGTATCGATTGGAAAGGAGGTACAAGCGATGATGGAAAAACTTAAAGAAATA 3′ (N terminal) and 5′ TAATGGCTGCAGATATTTTTATCTCCTTAA 3′ (C terminal) for MJ0831, 5′ TAATGTATCGATTGGAAAGGAGGTACAAGCGATGGAAAATTGGGTAGAATTGAAA 3′ (N terminal) and 5′ TAATGGCTGCAGATATTTTTATCTCAAAGC 3′ (C terminal) for MJ0977, and 5′ TAATGTATCGAT TGGAAAGGAG GTACAAGCGATGATAG TAAAG TG TCCAAT T TG T 3′ (N terminal) and 5′ TAATGGCTGCAGTATTTTTTATTGCTCTTT 3′ (C terminal) for MJ1198. The N-terminal primers contain a ClaI restriction site and a ribosome-binding site (underlined). The C-terminal primers contain a PstI restriction site. PCR products were digested with ClaI and PstI and ligated into compatible sites on the low-copy-number vector pWSK29 (12) to produce pLAR101, pLAR102, and pLAR103, respectively. Plasmid pSTL132 contains the ApaI-SacII fragment of pSTL175 (10) cloned into identical sites on pWSK29. A low-copy-number vector was chosen because of toxicity exhibited by E. coli recJ when present on a high-copy-number plasmid.

UV survival assays.

Complementation experiments were carried out with plasmids pWSK29, pLAR101, pLAR102, pLAR103, and pSTL132, described above. Plasmids were introduced by electroporation (5) into the E. coli K-12 strain STL3266 [F− λDE3 recB21 recC22 sbcA23 recJ284::Tn10 thi-1 argE3 hisG4 Δ(gpt-proA)62 thr-1 leuB6 kdgK51 rfbD1 ara-14 lacY1 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 tsx-33 supE44 rpsL31], a λDE3 lysogen carrying an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible T7 RNA polymerase gene. Transformants were grown overnight on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (1.5%) plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and tetracycline (15 μg/ml) (LB+Ap+Tc agar). Individual transformants were selected, and cells were grown in liquid LB+Ap+Tc medium to exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.6). Cultures were split, and one half was induced with 1 mM IPTG. Both sets of cultures were grown for 1 h, serially diluted in 56/2 buffer (13), and plated on LB+Ap+Tc agar plates. Plates were incubated at 45°C for 15 min, exposed to a 0-, 1-, 2-, or 5-J/m2 dose of UV (254 nm) irradiation, and incubated at 45°C in the dark for an additional 15 min and then overnight at 37°C. Fractional survival was calculated as the number of CFU on irradiated plates relative to the number of CFU on unirradiated plates.

Protein expression.

E. coli K-12 strain STL2329 [λDE3 sbcB15 recJ284::Tn10 endA Δ(xth-pncA gal thi)], a λDE3 lysogen carrying an IPTG-inducible T7 RNA polymerase gene, was used to express the protein products of MJ0831, MJ0977, and MJ1198 from pLAR101, pLAR102, and pLAR103, respectively. Cells were grown at 37°C in liquid LB+Ap+Tc medium to exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.8). IPTG (2 mM final concentration) was added to induce plasmid-encoded gene expression, and the culture was incubated for an additional hour. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.01 volume of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–10% sucrose (wt/vol), and stored at −70°C. To thawed cell suspensions, EDTA, lysozyme, and dithiothreitol were added to final concentrations of 4 mM, 1.5 mg/ml, and 0.8 mM, respectively. Cells were lysed by incubation at 4°C for 30 min followed by heat shock at 37°C for 5 min. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and the subsequent crude extracts were assayed as described below.

Nuclease assays.

Uniformly labeled bacteriophage T7 3H-DNA was prepared as previously described (7) with [3H]thymidine (Dupont NEN). End-labeled substrates were prepared from linearized 3-kb pBSSK− plasmid DNA and purified with Qiagen QiaExII kits. 3′-End-labeled substrate was generated from XbaI-digested pBSSK− by “fill-in” synthesis with the E. coli DNA polymerase I large fragment (New England Biolabs) in the presence of [α-−32P]dATP (Dupont NEN). 5′-End-labeled substrate was generated from HindIII-digested pBSSK− DNA, treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase (United States Biochemical Corp.), and phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-−32P]ATP (Dupont NEN).

Enzyme assays were done with either 0.5 μg (1.5 nmol) of T7 3H-DNA or 0.2 μg (0.2 pmol of ends) of 3′- or 5′-end-labeled substrate. Standard reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.5) (measured at 65°C), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.67 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) per ml in a 50-μl volume. Substrate DNA was heat denatured by incubation at 100°C for 5 min, followed by quenching on ice. When required, crude extracts were diluted in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 mg of BSA per ml. Protein samples or sample dilutions (2 μl) were added to reaction mixtures, which were then incubated at 65°C for 20 min. Trichloroacetic acid precipitation and determination of soluble radioactivity were performed as described previously (9). Protein concentrations of the crude extracts were determined by the Bradford method (3) with a reagent from Bio-Rad and BSA as the standard. One unit of nuclease activity corresponds to the release of 1 nmol of acid-soluble product.

RESULTS

Sequence comparison of archaeal hypothetical proteins with eubacterial RecJ and polyphosphatase PPX1 of yeast.

Database searches of eubacterial genomes with E. coli RecJ and the gapped BLASTP program (1) revealed 14 sequences that define seven conserved sequence motifs (10) (Fig. 1A). Individual pairwise alignments from such searches yielded E values (the probability of matching by chance) of 10−21 to 10−69, indicating very strong similarity with E. coli RecJ exonuclease, including open reading frames from the diverse genera Aquifex, Bacillus, Borrelia, Chlamydia, Chlamydophila, Erwinia, Haemophilus, Helicobacter, Rickettsia, Synechocystis, and Treponema. Both Bacillus subtilis and Helicobacter pylori carry two RecJ-related sequences, one with somewhat less similarity to E. coli RecJ. (The second Bacillus sequence is encoded on an SPβ2 prophage.)

Twenty open reading frames with similarity to the E. coli RecJ sequence can be found in the four archaeal species M. jannaschii, A. fulgidus, M. thermoautotrophicum, and P. horikoshii (Fig. 1) with iterative PSI-BLAST (1) searches of the National Center for Biotechnology Information DNA database (http://www/ncbi/nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). The PSI-BLAST program allows the database to be searched iteratively, first with a “seed” sequence and then with a matrix of related proteins, with position-specific scoring. Highly conserved motifs among otherwise weakly related proteins can therefore be more easily identified. These archaeal RecJ-related sequences can be placed into seven groups based on strong mutual similarity (E, <10−25). The sequence relationships between certain representative members of groups A to H are given in Table 1. Group A includes the eubacterial sequences epitomized by the E. coli RecJ exonuclease. The second group (Fig. 1B) includes seven archaeal sequences with the strongest overall similarity to the eubacterial RecJ sequence. This group includes two sequences from M. jannaschii that we have chosen to examine in this study: MJ0977 and MJ0831. Although not necessarily strongly homologous to the E. coli RecJ sequence (as can be seen in Table 1), the members of group B show strong similarity to one or more of the eubacterial RecJ sequences (usually from the chlamydiae, Bacillus, or Borrelia), with E values of 10−3 to 10−9. Group C has a single member, AF0075, which is similar to members of group B and to the eubacterial RecJ sequence (Table 1). AF0075 is most similar to the Rickettsia prowazekii RecJ sequence, with an E value of 10−5. Group D includes four archaeal sequences (MJ1198, AF1337, MTH0763, and PHO0340) with predicted proteins larger than RecJ and an N-terminal extension with homology to DnaJ, an E. coli chaperonin. These sequences are highly related to each other, with pairwise BLASTP E values ranging from 10−92 to 10−159. We have chosen to examine MJ1198 from this group. The MJ1198 product is significantly similar in its C-terminal portion to Borrelia RecJ (E, 3 × 10−5). Group E includes a single member, AF0291, whose product is only very weakly similar to those of other groups or to RecJ (Table 1). Groups F and G include sequences from two or more archaeal genera which are strongly similar (E for group F, 10−45; E for group G, 10−84 to 10−87); groups F and G are themselves related (Table 1). Group H includes two sequences whose products have been annotated as polyphosphatases based on similarity to S. cerevisiae PPX1 metaphosphatase. Members of groups E, F, G, and H have no significant homology in pairwise BLASTP alignments to any of the eubacterial RecJ sequences. However, members of groups F and G are similar to another group of eubacterial sequences, including those from the mycoplasmal MgPa and P1 cytoadhesion operons, a domain from several poly(A) polymerases, and sequences for numerous B. subtilis hypothetical proteins (including YtiQ, YybT, and YybQ) (2).

TABLE 1.

E values from pairwise BLASTP alignments between representative protein sequencesa

| Sequence |

E value for:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco RecJ | MJ0977 | MJ0831 | AF0075 | MJ1198 | AF00291 | MJ0988 | MJ1633 | MJ0608 Ppx1 | Sce PPX1 | |

| Eco RecJ | >10 | 0.018 | >10 | 0.26 | 3.3 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | |

| MJ0977 | 6 × 10−26 | 9 × 10−15 | >10 | 3.3 | 0.61 | 0.27 | >10 | >10 | ||

| MJ0831 | 6 × 10−11 | >10 | 6.3 | 6.3 | >10 | >10 | >10 | |||

| AF0075 | 0.55 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | ||||

| MJ1198 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | |||||

| AF0291 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | ||||||

| MJ0988 | 10−18 | 0.20 | >10 | |||||||

| MJ1633 | 0.31 | 0.35 | ||||||||

| MJ0608 Ppx1 | 2 × 10−7 | |||||||||

| Sce PPX1 | ||||||||||

Alignments were performed with the gapped BLASTP program (1), the BLOSUM62 matrix, and gap penalties of 11 (open) and 1 (per residue extension) with a lambda ratio of 0.85. Eco, E. coli sequence; Sce, S. cerevisiae sequence. MJ and AF prefixes indicate proteins encoded by the archaea M. jannaschii and A. fulgidus, respectively.

Cloning of RecJ-related genes from Methanococcus and genetic complementation of recJ in E. coli.

To assess the ability of the methanococcal genes to complement a recJ mutation, the open reading frames MJ0977, MJ0831, and MJ1198 were amplified by PCR from M. jannaschii chromosomal DNA, fused to a ribosome-binding site sequence, and cloned into a low-copy-number expression vector of E. coli. The plasmid derivatives were introduced by transformation into an E. coli recJ mutant strain, STL3266, and tested for their ability to enhance UV survival. A T7 phage promoter on the vector controls expression of the genes. The addition of IPTG to the growth medium triggers the expression of the genes by induction of T7 RNA polymerase from a resident λDE3 lysogenic phage.

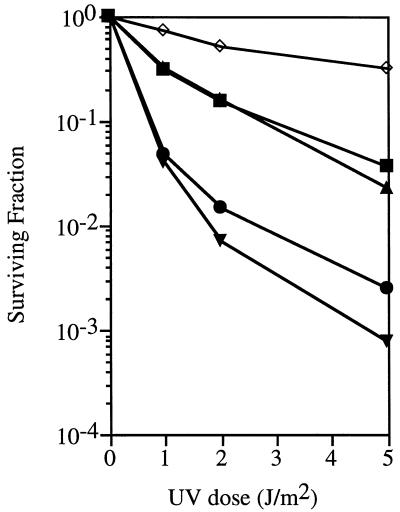

To promote the functionality of the potentially thermophilic proteins, the growth temperature was raised to 45°C both prior to and immediately after irradiation. With this regimen, both MJ0977 and MJ0831 exhibited partial complementation of the recJ mutation. The presence of MJ0977 or MJ0831 in strain STL3266 resulted in ∼50-fold and ∼25-fold increases in survival at a UV dosage of 5 J/m2, respectively (Fig. 2). Complementation was dependent on the induction of the MJ0831 and MJ0977 genes with the addition of IPTG, as no substantial complementation was observed in its absence (data not shown). In contrast, MJ1198 had weak or no ability to complement the recJ mutation. E. coli recJ expression restored UV survival fully (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

UV survival of E. coli STL3266 transformed with plasmids containing M. jannaschii genes, E. coli recJ, or the vector alone. Symbols: ▾, vector; ◊, E. coli recJ; ▴, MJ0831; ■, MJ0977; ●, MJ1198. Values are the means of five or more experiments.

Overexpression and characterization of MJ0977 nuclease activity.

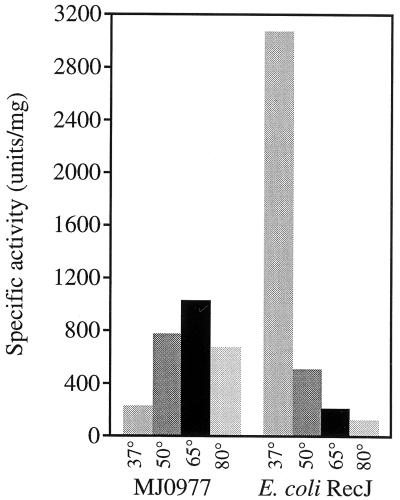

Plasmids pLAR101, pLAR102, and pLAR103 were introduced into STL2329 for protein expression. Crude extracts were prepared from cells induced for expression of each of the three methanococcal genes. Extracts were tested for the ability to degrade a uniformly 3H-labeled T7 DNA substrate. At 37°C, extracts from cells expressing the MJ0977-encoded protein exhibited a sixfold increase in nuclease activity over cells carrying the vector alone (Fig. 3). No increased DNase activity was evident in extracts from cells expressing the product of MJ0831 or MJ1198 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Thermostability of ssDNA nuclease activity in crude extracts of cells induced for the expression of the MJ0977 product or E. coli RecJ. Nuclease assays were performed under standard conditions (as described in Materials and Methods) with noted temperature variations. The specific ssDNA nuclease activity of extracts from cells containing the vector alone was <35 U/mg of protein.

To assess the thermostability of MJ0977-encoded nuclease activity, extracts of MJ0977-expressing cells were also tested at higher reaction temperatures. Crude extracts from cells expressing E. coli RecJ were used for comparison. E. coli RecJ DNase activity was optimal at 37°C and was reduced significantly when the reaction temperature was increased (Fig. 3). In contrast, the nuclease activity of extracts from MJ0977-expressing cells increased significantly when the reaction temperature was above 37°C and was optimal at 65°C. At 65°C, MJ0977-expressing cells exhibited nuclease activity 30-fold above that of cells carrying the vector alone. The DNase activity in extracts of cells expressing MJ0977 was ssDNA specific: no activity was detected on double-stranded DNA in comparable reactions at 65°C relative to the results for cells expressing the vector alone (data not shown). Nearly 65% of the ssDNase activity in extracts of MJ0977-expressing cells was retained when the reaction temperature was raised to 80°C (Fig. 3), demonstrating the thermostability of the protein.

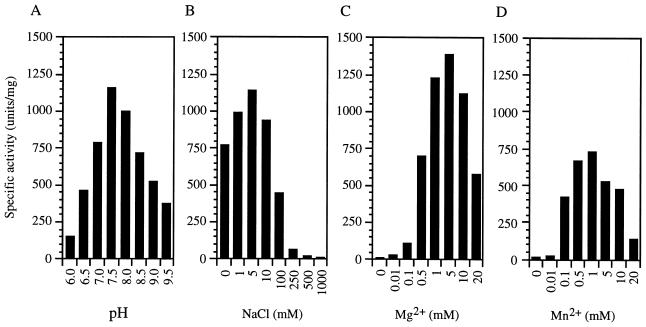

As with E. coli RecJ, the MJ0977-associated nuclease activity was dependent on the presence of a divalent cation. In reactions at 65°C, both Mg2+ and Mn2+ are effective cofactors for MJ0977, with optimal concentrations of 5 and 1 mM, respectively (Fig. 4C and D). No activity was detected when Co2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Ca2+, or Zn2+ was used as a cofactor (data not shown). The activity was optimal in the presence of 5 mM NaCl, and increasing the NaCl concentration above 10 mM resulted in a significant loss of activity (Fig. 4B). The optimal pH for MJ0977-associated nuclease activity was 6.5 at 65°C (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Optimization of nuclease activity on ssDNA in crude extracts of cells induced for the expression of the MJ0977 product. T7 nuclease assays were performed at 65°C under standard conditions (as described in Materials and Methods) with noted variations in Tris buffer pH (measured at 65°C) (A), NaCl concentration (B), Mg2+ concentration (C), or Mn2+ concentration in the absence of Mg2+ (D).

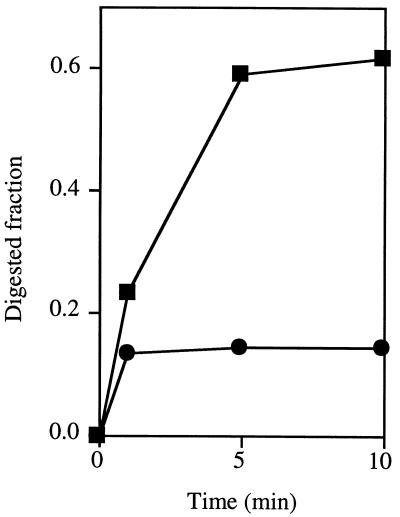

To determine the polarity of degradation, MJ0977 DNase activity was tested on end-labeled ssDNA substrates approximately 3,000 bases in length. Protein extracts from strains expressing MJ0977 were efficient at releasing the terminal nucleotide from 5′ ssDNA ends but not from 3′ ssDNA ends (Fig. 5). Whereas more than 60% of 5′ ends were released by the MJ0977 product after only 10 min, less than 20% of 3′ ends were released in the same interval. This property of the MJ0977 product is similar to that of E. coli RecJ, which degrades ssDNA processively in a 5′-to-3′ direction (9; S. T. Lovett, unpublished results).

FIG. 5.

DNA end preference of the expressed MJ0977 product. Values were derived by subtracting the fraction of acid-soluble radioactivity released by extracts from cells expressing MJ0977 from that released by extracts from cells containing the vector alone. Symbols: ■, 5′-end-labeled ssDNA substrate; ●, 3′-end-labeled substrate.

DISCUSSION

RecJ-related sequences appear to be especially abundant in archaeal genomes. Alignments of these diverged archaeal sequences define several groups that share sequence motifs with eubacterial RecJ exonucleases. We sought to determine which, if any, of these sequences had functional similarity to RecJ. We have demonstrated that two sequences from M. jannaschii, MJ0831 and MJ0977, members of the group with the strongest similarity to eubacterial RecJ sequences, can partially complement a recJ mutation in E. coli K-12. This result indicates a conservation of function between these proteins and E. coli RecJ. A third opening reading frame, MJ1198, yielded complementation too weak to assess its functional relevance.

The expression of one of the genes, MJ0977, resulted in high levels of a thermostable ssDNA nuclease activity. This nuclease had many properties in common with E. coli RecJ (9): it was highly specific for ssDNA, required Mg2+ or Mn2+ as a cofactor, and attacked 5′ ends with a higher avidity. Despite overall weak sequence similarity between the MJ0977 product and E. coli RecJ (Table 1), these genetic and biochemical data support the contention that these proteins are indeed functionally related.

Failure to achieve complete genetic complementation with MJ0977 or MJ0831 was not unexpected. Because M. jannaschii is a thermophilic organism, its proteins may be less apt to function in a mesophilic organism such as E. coli. In addition, different biochemical properties, such as a lower affinity for substrate, catalytic rate, processivity, or a failure to interact properly with other E. coli proteins, may account for incomplete functionality in E. coli.

Although both MJ0977 and MJ0831 demonstrated similar abilities to complement an E. coli recJ mutation, we detected ssDNA nuclease activity associated only with the expression of MJ0977. A failure to detect nuclease activity for MJ0831 could have been due to poorer stability in E. coli or to enzymatic requirements not supplied by our reaction conditions. The two proteins might also differ in their thermostability: if the MJ0831 product is considerably less thermostable than the MJ0977 product, it might be difficult to detect over the background of nucleases in E. coli crude extracts. Further purification of the MJ0831-encoded peptide should clarify this issue.

The aspartate, histidine, and arginine residues found in conserved motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 of the E. coli RecJ exonuclease have been shown to be important for its biological and biochemical functions (10). Most of these residues are also conserved among the archaeal groups (Fig. 1). Some of these motifs may define residues that interact with the catalytic divalent metal ion(s) required for phophoesterase activity. In E. coli RecJ, mutation of the aspartate residues in motifs 1, 3, and 4 results in a dominant-negative phenotype in vivo and a complete loss of nuclease activity in vitro (10). In the archaeal proteins, one aspartate (corresponding to D79 of motif 1 of E. coli RecJ) has been replaced by histidine and displaced in its position within motif 1 for groups F, G, and H. The DHH of motif 3 is probably the most diagnostic of this family of proteins (2) and, accordingly, all three residues are essential for E. coli RecJ activity (10). The NP of motif 3A, invariant in the eubacterial RecJ proteins, is reduced to a single proline or absent in most of the archaeal sequences, with groups B and D as the exceptions. Motif 5, barely recognizable among some members of group B, is missing or not recognizable (perhaps reduced to a single lysine or arginine) in the other groups. Mutations in this motif have not yet been assayed for their impact on the activity of E. coli RecJ exonuclease. In motif 6, only the arginine is invariant; in E. coli RecJ, mutation of this residue to alanine results in a complete loss of exonuclease activity and a recessive mutant phenotype. Although the glycine richness of motif 7 is conserved among archaeal groups, the histidine often is not, and the motif is entirely missing in the methanococcal Ppx1 sequence. This lack of conservation may not be so surprising, since the mutation of motif 7 histidine to alanine in RecJ exonuclease produced a somewhat leaky phenotype (10).

Because of the high degree of sequence similarity among E. coli RecJ nuclease, the MJ0977 product, and the products of the group B sequences (Fig. 1B), we think it is likely that all group B proteins are nucleases for DNA or RNA. Although it is tempting to speculate, based on sequence similarity, that group C and D proteins are also nucleases and that group F, G, and H proteins are phosphatases, further experimentation is required to assign a biological substrate to these proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant RO1 GM43889 from the National Institutes of Health and by predoctoral training grants T32 GM07122 and F31 GM19179 to L.A.R.

We thank Steven Sandler of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst for providing us with M. jannaschii chromosomal DNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind L, Koonin E V. A novel family of predicted phosphoesterases includes Drosophila Prune protein and bacterial RecJ exonuclease. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:17–19. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dianov G, Sedgwick B, Daly G, Olsson M, Lovett S, Lindahl T. Release of 5′-terminal deoxyribose-phosphate residues from incised abasic sites in DNA by the Escherichia coli RecJ protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:993–998. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grilley M, Griffith J, Modrich P. Bidirectional excision in methyl-directed mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11830–11837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinkle D C, Chamberlin M J. Studies of the binding of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase to DNA. I. The role of sigma subunit in site selection. J Mol Biol. 1972;70:157–185. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lovett S T, Clark A J. Genetic analysis of the recJ gene of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:190–196. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.1.190-196.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovett S T, Kolodner R D. Identification and purification of a single-strand-specific exonuclease encoded by the recJ gene of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2627–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutera V A, Jr, Han E S, Rajman L A, Lovett S T. Mutational analysis of RecJ exonuclease of Escherichia coli: identification of phosphoesterase motifs. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6098–6102. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6098-6102.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viswanathan M, Lovett S T. Single-strand DNA specific exonucleases in Escherichia coli: roles in repair and mutation avoidance. Genetics. 1998;249:7–16. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willetts N S, Clark A J, Loco B. Genetic location of certain mutations conferring recombination deficiency in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1969;97:244–249. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.1.244-249.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wurst H, Kornberg A. A soluble exopolyphophatase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10996–11001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wurst H, Shiba T, Kornberg A. The gene for a major exopolyphosphatase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:898–906. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.898-906.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]