Abstract

Objective

The present study aims to analyze the psychometric properties and general validity of the Caregiver Reported Early Development Instruments (CREDI) short form for the population-level assessment of early childhood development for Brazilian children under age 3.

Method

The study analyzed the acceptability, test-retest reliability, internal consistency and discriminant validity of the CREDI short-form tool. The study also analyzed the concurrent validity of the CREDI with a direct observational measure (Inter-American Development Bank's Regional Project on Child Development Indicators; PRIDI). The full sample includes 1,265 Brazilian caregivers of children from 0 to 35 months (678 of which comprising an in-person sample and 587 an online sample).

Results

Results from qualitative interviews suggest overall high rates of acceptability. Most of the items showed adequate test-retest reliability, with an average agreement of 84%. Cronbach's alpha suggested adequate internal consistency/inter-item reliability (α > 0.80) for the CREDI within each of the six age groups (0–5, 6–11, 12–17, 18–23, 24–29 and 30–35 months of age). Multivariate analyses of construct validity showed that a significant proportion of the variance in CREDI scores could be explained by child gender and family characteristics, most importantly caregiver-reported cognitive stimulation in the home (p < 0.0001). Regarding concurrent validity, scores on the CREDI were significantly correlated with overall PRIDI scores within the in-person sample at r = 0.46 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The results suggested that the CREDI short form is a valid, reliable, and acceptable measure of early childhood development for children under the age of 3 years in Brazil.

Keywords: Child development, Measurement, Validation studies, Population assessment, Brazil

Resumo

Objetivo

O presente estudo visa analisar as propriedades psicométricas e a validade geral do formulário curto dos Instrumentos sobre o Desenvolvimento na Primeira Infância Relatado por Cuidados (CREDI) para avaliação em nível populacional do desenvolvimento na primeira infância de crianças brasileiras com menos de três anos.

Método

O estudo analisou a aceitabilidade, a confiabilidade teste-reteste, a consistência interna e a validade discriminante da ferramenta CREDI. O estudo também analisou a validade concorrente do CREDI com uma medida observacional direta (Projeto Regional sobre os Indicadores de Desenvolvimento na Infância do Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento; PRIDI). A amostra total inclui 1.265 cuidadores brasileiros de crianças de 0 a 35 meses (678 em uma amostra presencial e 587 em uma amostra on-line).

Resultados

Os resultados das entrevistas qualitativas sugerem altas taxas gerais de aceitabilidade. A maior parte dos itens mostrou confiabilidade teste-reteste adequada, com concordância média de 84%. O coeficiente alfa de Cronbach sugeriu consistência interna/confiabilidade entre itens (α > 0,80) para o CREDI em cada uma das seis faixas etárias (0-5 α = 6-11, 12-17, 18-23, 24-29 e 30-35 meses de idade). As análises multivariadas da validade do constructo mostraram que uma proporção significativa da variação nas pontuações do CREDI pode ser explicada pelo sexo da criança e pelas características familiares, mais importante o estímulo cognitivo em casa relatado pelo cuidador (p < 0,0001). Com relação à validade concorrente, as pontuações do CREDI foram significativamente correlacionadas às pontuações gerais do PRIDI na amostra presencial em r = 0,46 (p < 0,001).

Conclusões

Os resultados sugerem que o formulário curto CREDI é uma medida válida, confiável e aceitável de desenvolvimento na primeira infância para crianças com menos de três anos no Brasil.

Palavras-chave: Desenvolvimento infantil, Medicação, Estudos de validação, Avaliação da população, Brasil

Introduction

A strong foundation in early development is a prerequisite for individual health and well-being, as well as harmonious societies.1 The importance of early childhood development (ECD) is well reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which mandate access to early care and educational opportunities for young children around the world by 2030.2 Investments in ECD services are particularly necessary in low- and middle-income countries, where the proportion of children who are not reaching their developmental potential remains high.2, 3

Consistent monitoring of ECD needs and outcomes using culturally and developmentally appropriate measures is a key to ensuring the success of interventions.4, 5 Population measures of ECD encourage a focus on children's abilities in multiple domains, and can be used to compare large groups of children and to track overall progress of population of children.6 These assessments can leverage culturally relevant, evidence-based ECD policies and targeted investments to improve the potential of a nation's young children.7 In recent years, measures of children's ECD status have been developed for large-scale use, including the UNICEF's Early Childhood Development Index (ECDI), which assesses children aged 36–59 months,8 and the Inter-American Development Bank's Regional Project on Child Development Indicators (PRIDI), which evaluates children aged 2 to almost 5 years through direct observation.9 Much less information is currently available on the development of children under the age of 3, among whom direct assessments tend to be more limited in scope and are generally harder to implement.

In this context, we examine the short form of the Caregiver Reported Early Development Instruments (CREDI; available in Supplementary Material Appendix A), which was developed as a new caregiver-reported instrument for assessing the overall development of children under the age of 3.10 The aim of the CREDI short form is to provide conceptually rich, developmentally informed, population-level data on global progress in alleviating ECD-related inequities and meeting target 4.2 of the SDGs.10

The Brazilian context

Brazil's recent early childhood legislation (Marco Legal da Primeira Infância) establishes principles and guidelines for public policies, including programs that educate families to stimulate children's development.11 This legislation highlights that public childhood programs need to involve monitoring and systematic data collection and the dissemination of these evaluation results.11 However, neither needs assessments nor impact evaluations will be feasible without adequate instruments to assess child development.

Previous studies have reviewed tools used in Brazil to assess ECD and screen for developmental difficulties.12, 13, 14 The most commonly used and cited tools are the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) and the Denver Developmental Screening Test. An adapted version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) has also been used in Brazil.15 Despite the utility of these individual-level assessments, several limitations have been identified for the large-scale use of these tools, including the relatively high cost associated with application kits, test administration fees, materials, and highly trained professionals.16 Another challenge is that most of the instruments used in Brazil were developed in high-income countries, and have not yet been culturally validated in other contexts.13, 14 Instruments that assess population-level development in a cheap and scalable fashion are not currently available in Brazil, which makes comparisons within and across countries currently impossible.

The present study

In the present study, we aim to analyze the validity of the CREDI short form for the population-level assessment of ECD for Brazilian children under the age of 3. To do so, we analyze the acceptability, test-retest reliability, internal consistency, construct validity, and concurrent validity of the CREDI.

Methods

Study sample and procedures

The study includes two samples: a sample of children from São Paulo (southeast Brazil) previously enrolled in an intervention study and interviewed in-person, and an online sample with participants from different parts of Brazil. The in-person sample comprises 678 children aged 28–35 months, and the online sample includes 587 children aged 0–35 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample.

| n | Mean (%) | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-person sample | 678 | ||||

| Child – female | 353 | 52.1% | |||

| Child age (months) | 678 | 31.92 | 1.87 | 27.73 | 37.08 |

| Children experiencing stunting (HAZ <−2) | 35 | 5.4% | |||

| Caregiver education | 659 | ||||

| Lower than secondary schooling | 249 | 37.8% | |||

| Secondary schooling | 366 | 55.5% | |||

| Higher education | 44 | 6.7% | |||

| Asset quintile (1–5) | 600 | 2.97 | 1.42 | 1 | 5 |

| Home stimulation score (0–6) | 672 | 4.94 | 1.42 | 0 | 6 |

| Online sample | 587 | ||||

| Child – female | 263 | 44.8% | |||

| Child age (months) | 587 | 21.0 | 8.62 | 0 | 35 |

| Caregiver education | 579 | ||||

| Lower than secondary schooling | 14 | 2.42% | |||

| Secondary schooling | 175 | 30.22% | |||

| Higher education | 390 | 67.4% | |||

| Socioeconomic (0–100) | 551 | 62.83 | 19.69 | 0 | 100 |

| Home stimulation score (0–6) | 587 | 4.86 | 1.19 | 1 | 6 |

n, number of participants; SD, standard deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum.

Height measures were converted into normed height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) using the World Health Organization Anthro software package.

All children in the in-person sample are part of the Western Region Birth Cohort, which includes all children born between October 2013 and March 2014 at the University Hospital of São Paulo. These children represent approximately 80% of all children in the public health system of the area and are primarily from low- and middle-income families living in São Paulo's western region. A total of 900 caregivers were randomly selected from the larger cohort and agreed to participate in the PRIDI assessment. These 900 children do not differ from the rest of the cohort with respect to any observable characteristics. From these, 678 mother-child dyads completed the study including all child development assessments.

The online sample was recruited through a Facebook group run by a Brazilian pediatrician that provides pediatric health and wellness information (e.g. healthy eating and disease prevention). A total of 1265 caregivers expressed interest in the study by clicking on the Facebook link. Of these, 587 caregivers completed all sections of the online survey and were thus included in this study. Participants who reported their geographical information (n = 523; 89%) were from five regions of Brazil (Southeast, 66%; South, 16%; Northeast, 12%; Midwest, 5%; and North, 1%). Mothers in this group were on average substantially more educated than the Brazilian average.

A smaller sample of 38 caregivers was recruited from the in-person sample in São Paulo to take part in brief cognitive interviews designed to assess understanding and appropriateness of the CREDI items within the Brazilian cultural setting. This subsample was recruited according to mothers’ availability and was stratified by children's gender and age, ensuring representation of boys/girls and older/younger children. Demographic characteristics for these caregivers were generally similar to those of the broader São Paulo cohort.

Ethical considerations

The study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. The São Paulo data collection was done as part of protocol number 890.325 approved by the University Hospital of Universidade de São Paulo's (HU-USP) IRB. All caregivers were informed about the objectives of the study and provided informed consent prior to answering the study's questions.

Measures

CREDI

The CREDI is an internationally developed, population-level measure for assessing the overall development of children aged 0–35 months across the motor, language, cognition, socioemotional, and mental health domains. This tool was designed to be usable within large-sample data collection efforts, and to be culturally neutral with items that are not affected by culturally specific contexts.10 This open-source tool can be downloaded freely from the CREDI website (https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/credi/). The CREDI is administered directly to the child's primary caregiver using a yes/no response scale. There are two versions of the CREDI. The short form (which is the focus of the present study) creates a summary score for children's overall developmental status, whereas the long form creates domain-specific developmental scores. The short form includes 20 items specific to each six-month age group (0–5 months, 6–11 months, 12–17 months, 18–23 months, 24–29 months, and 30–35 months), and the administration time is on average five minutes. The CREDI is scored continuously using age-standardized scoring procedures that are based on children's raw percent “yes” (pass) responses within each age group. The short form was originally developed based on an extensive multi-stage, multi-country pilot effort that included both quantitative and qualitative data analysis focusing on the items’ psychometric properties and cultural and developmental appropriateness.10 In the present paper, we specifically focus on the performance of the CREDI short form items in Brazil. All items were translated to and from Brazilian Portuguese by native speakers.

PRIDI

A direct assessment tool of children aged 24–59 months, including 21 items for capturing four domains of ECD: cognition, communication and language, socioemotional, and motor.9 For the present study, the PRIDI was only administered to children aged 2–3 years in the São Paulo in-person cohort.

Household stimulation

Caregivers in both samples reported on cognitive stimulation using items from UNICEFs Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey ECD module capturing adult-child interactions in six different activities (e.g. reading, telling stories, and playing), over the preceding three days. Stimulation scores represent the total number of activities endorsed by caregivers (range = 0–6), with higher scores indicating more stimulation.

Asset quintile (1–5)

For the in-person sample, we followed a methodology to classify participating households into wealth quintiles.17 Principal component analysis of the following variables was conducted: household ownership of a motorbike or car, number of bathrooms in the household, as well as child ownership of picture books, bed, and separate bedroom.

In the online sample, all respondents were directly asked to assess their income relative to others on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 meaning poorer than everyone else, 50 meaning average, and 100 meaning higher income than everyone else. This assessment was based on similar measures of relative socioeconomic status (SES).18 This information was used to divide the sample into quintiles.

Data analysis

The CREDIs acceptability in Brazil was assessed using 38 qualitative interviews conducted by a trained Brazilian data collector with families living in São Paulo: 18 interviews focused on items in the cognitive and language domains and 20 focused on items in the socioemotional and mental health domains. Each caregiver responded to the CREDI item and then was asked to discuss in her/his own words the meaning of the question. Two independent coders (including the data collector and a CREDI team member) rated the caregivers’ understanding of the item as either matching with the original item intent (1) or not (0). When coders disagreed, a third CREDI team member served as a tiebreaker. Items were deemed to be well understood if at least 80% of caregivers received a score of 1.

To analyze test-retest reliability, 120 caregivers within the in-person sample from São Paulo were interviewed using the CREDI twice over the course of approximately ten days. Kappa statistics were computed to assess the alignment of responses between the two interviews. Additionally, overall agreement (percentage of caregivers providing the same answer) for each item was calculated. Cronbach's alpha was computed for each of the six age groups to assess the internal consistency of the CREDI.

Construct validity was assessed using a hypothesis-testing method.19 The in-person and online samples were assessed using separate linear regression models examining score differentials with respect to child and family characteristics, including child age, gender, stunting status (only for the in-person sample), household stimulation, SES, and maternal education levels. Based on prior ECD research, our hypothesis was that children who were female, had caregivers with higher education and SES, and came from high-stimulation households would demonstrate higher CREDI scores. Concurrent criterion validity was assessed by correlating scores from the CREDI with scores from the PRIDI direct assessments conducted as part of the in-person interviews in older children in São Paulo. Associations between the CREDI and the PRIDI were compared within subgroups based on caregiver education level as an initial step in testing for invariance. All analyses were conducted using the Stata statistical software program (version 14).

Results

Qualitative interviews revealed an overall high acceptability of the scale, as well as high degrees of cognitive understanding of items. Most items were clearly understood by more than 80% of caregivers. One socioemotional item demonstrated 75% understanding, and two cognitive items demonstrated 75% and 67% understanding, respectively. No issues were detected with any of the items, and the participants were cooperative with and felt pleased by the items. As such, and given that these same items demonstrated greater than 80% understanding across countries, all items were retained at this stage.

Results indicated that most of the items showed adequate test-retest reliability, with an average agreement of 84%, and a minimum agreement of 75% across all age groups (Table 2). In terms of kappa, five items showed excellent reliability (kappa > 0.80), 32 items showed substantial reliability (kappa > 0.60), and 15 items showed moderate reliability (kappa > 0.40). Ten items, most of the socioemotional domain, showed fair to low reliability (≤0.40).

Table 2.

Test–retest reliability over 10 days in subsample of participants.

| Item Number - Question | Kappa | Agreement | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 - Does the child smile when others smile at him/her? | 0.27 | 0.89 | 36 |

| A2 - Does the child grasp onto a small object (e.g. your finger, a spoon) when put in his/her hand? | 0.27 | 0.89 | 35 |

| A3 - Does the child recognize you or other family members (e.g. smile when they enter a room or move toward them)? | 0.80 | 0.94 | 36 |

| A4 - Does the child show interest in new objects by trying to put them in his/her mouth? | 0.56 | 0.84 | 37 |

| A5 - When lying on his/her stomach, can the child hold his/her head and chest off the ground using only his/her hands and arms for support? | 0.79 | 0.91 | 35 |

| A6/B1 - Can the child pick up a small object (e.g. a small toy or small stone) using just one hand? | 0.42 | 0.78 | 36 |

| A7 - When lying on his/her back, does the child grab his/her feet? | 0.47 | 0.82 | 33 |

| A8/B6 - Does the child look at an object when someone says “look!” and points to it? | 0.62 | 0.86 | 35 |

| A9/B4 - Does the child look for an object of interest when it is removed from sight or hidden from him/her (e.g. put under a cover, behind another object)? | 0.71 | 0.89 | 37 |

| A10/B3 - Does the child intentionally move or change his/her position to get objects that are out of reach? | 0.63 | 0.84 | 37 |

| A11/B2 - Does the child play by tapping an object on the ground or a table? | 0.69 | 0.85 | 34 |

| A12/B5 - Can the child hold him/herself in a sitting position without help or support for longer than a few seconds? | 0.77 | 0.89 | 36 |

| A13/B7 - Can the child pick up and eat small pieces of food with his/her fingers? | 0.63 | 0.87 | 69 |

| A14/B9 - Can the child transfer a small object (e.g. a small toy or small stone) from one hand to the other? | 0.78 | 0.94 | 65 |

| A15/B10 - Can the child use gestures to indicate what he/she wants (e.g. put arms up to indicate that he/she wants to be held, or point to water)? | 0.61 | 0.87 | 68 |

| A16/B8 - Can the child crawl, roll, or scoot forward on his/her own? | 0.85 | 0.94 | 67 |

| A17/B12 - Can the child throw a small ball or small stone in a forward direction using his/her hand? | 0.67 | 0.88 | 68 |

| A18/B11 - Can the child pick up and drop a small object (e.g. a small toy or small stone) into a bucket or bowl while sitting? | 0.74 | 0.89 | 64 |

| A19/B13 - Can the child say one or more words (e.g. names like “Mama” or “ba” for “ball”)? | 0.86 | 0.95 | 110 |

| A20/B15 - Can the child walk several steps while holding on to a person or object (e.g. wall or furniture)? | 0.78 | 0.90 | 69 |

| C12 - Can the child drink from a cup (without a lid) on his/her own without spilling? | 0.66 | 0.84 | 67 |

| B14 - Does the child ask you for help using signs or words when he/she cannot do something on his/her own (e.g. to reach an object up high)? | 0.47 | 0.74 | 69 |

| B16/C2 - Can the child follow simple directions (e.g. “Stand up” or “Come here”)? | 0.83 | 0.92 | 66 |

| B17/C1 - Can the child maintain a standing position on his/her own, without holding on or receiving support? | 0.72 | 0.87 | 68 |

| B18/C7 - Can the child point to a person or object when asked (e.g. “Where is mama?” or “Where is the ball?”)? | 0.81 | 0.91 | 68 |

| B19/C4 - Can the child climb onto an object such as a chair or bench? | 0.75 | 0.88 | 65 |

| B20/C8 - Can the child kick a ball or other round object forward using his/her foot? | 0.85 | 0.92 | 66 |

| C3 - Does the child imitate others’ behaviors (e.g. washing hands or dishes)? | 0.53 | 0.92 | 74 |

| C5 - Is the child kind to younger children (e.g. speaks to them nicely and touches them gently)? | 0.28 | 0.85 | 74 |

| C6 - Does the child show curiosity to learn new things (e.g. by asking questions or exploring a new area)? | 0.54 | 0.91 | 74 |

| C9 - Does the child involve others in play (i.e. play interactive games with other children)? | 0.41 | 0.91 | 74 |

| C10 - Does the child show sympathy or look concerned when others are hurt or sad? | 0.22 | 0.86 | 72 |

| C11 - Can the child run more than a few steps without falling or bumping into objects? | 0.77 | 0.89 | 109 |

| C13 - Can the child stack three or more small objects (e.g. blocks, cups, bottle caps) on top of each other? | 0.75 | 0.88 | 108 |

| C14 - Can the child answer simple questions (e.g. “Do you want water?”) by saying “yes” or “no”, rather than nodding? | 0.73 | 0.87 | 67 |

| C15 - Does the child play by pretending objects are something else (e.g. imagining a bottle is a doll, a stone is a car, or a spoon is an airplane)? | 0.38 | 0.74 | 66 |

| C16/D3 - Can the child correctly name at least one family member other than mom and dad (e.g. name of brother, sister, aunt, uncle)? | 0.67 | 0.93 | 73 |

| C17/D2 - Can the child ask for something (e.g. food, water) by name when he/she wants it? | 0.77 | 0.95 | 75 |

| C18/D1 - Can the child walk backwards? | 0.43 | 0.76 | 70 |

| C19/D4/E1 - If you show the child an object he/she knows well (e.g. a cup or animal), can he/she consistently name it? | 0.65 | 0.85 | 73 |

| C20/D6/E2/F1 - Can the child say ten or more separate words (e.g. names like “Mama” or objects like “ball”)? | 0.65 | 0.84 | 75 |

| D5 - Can the child remove an item of clothing (e.g. take off his/her shirt)? | 0.62 | 0.85 | 74 |

| D7 - Can the child tell you when he/she is tired or hungry? | 0.70 | 0.92 | 75 |

| D8/E3/F4 - Can the child sing a short song or repeat parts of a rhyme from memory by him/herself? | 0.70 | 0.89 | 75 |

| D9/E4/F2 - Can the child jump with both feet leaving the ground? | 0.66 | 0.85 | 75 |

| D10/E7/F7 - Can the child correctly use any of these words: “I”, “you”, “she”, or “he” (e.g. “I go to store”, or “He eats rice”)? | 0.66 | 0.84 | 74 |

| D11/E6/F5 - Can the child correctly ask questions using any of these words: “what”, “which”, “where”, or “who”? | 0.56 | 0.78 | 72 |

| D12/E9/F8 - Can the child count up to five objects (e.g. fingers, people)? | 0.63 | 0.82 | 71 |

| D13/E5/F3 - Can the child speak using sentences with three or more words that go together (e.g. “I want water” or “The house is big”)? | 0.62 | 0.82 | 74 |

| D14/F10/E12 - If you show the child two objects or people of different size, can he/she tell you which one is the big one and which is the small one? | 0.49 | 0.75 | 72 |

| D15/E10/F9 - Can the child identify at least one color (e.g. red, blue, yellow)? | 0.63 | 0.82 | 71 |

| D16/ E17/ F12 - Can the child explain in words what common objects like a cup or chair are used for? | 0.40 | 0.70 | 76 |

| D17/E16/F15 - If you ask the child to give you three objects (e.g. stones, beans), does the child give you the correct amount? | 0.48 | 0.74 | 70 |

| D18/E14/F11 - If you point to an object, can the child correctly use the words “on”, “in”, or “under” to describe where it is (e.g. “The cup is on the table” instead of “The cup is in the table”)? | 0.30 | 0.69 | 36 |

| D19/E8/F6 - Does the child ask about familiar people other than parents when they are not there (e.g. “Where is the neighbor?”)? | 0.00 | 0.73 | 41 |

| D20/E15/F14 - Does the child ask “why” questions (e.g. “Why are you tall”)? | 0.52 | 0.77 | 39 |

| E11/F16 - Does the child often kick, bite, or hit other children or adults? | 0.23 | 0.69 | 42 |

| E13/F17 - Does the child become extremely withdrawn or shy in new situations? | 0.17 | 0.60 | 42 |

| E18/F13 - Can the child dress him/herself (e.g. put on his/her pants and shirt without help)? | 0.62 | 0.81 | 69 |

| E19/F19 - Can the child say what others like or dislike (e.g. “Mama doesn’t like fruit” “Papa likes football”)? | 0.46 | 0.74 | 42 |

| E20/ F20 - Can the child talk about things that have happened in the past using correct language (e.g. “Yesterday I played with my friend” or “Last week she went to the market”)? | 0.53 | 0.80 | 69 |

| F18 - Does the child frequently act impulsively or without thinking (e.g. running into the street without looking)? | 0.28 | 0.65 | 40 |

| Average | 0.58 | 0.84 | 62 |

| Average by age group 0–5 | 0.65 | 0.88 | |

| Average by age group 6–11 | 0.60 | 0.84 | |

| Average by age group 12–17 | 0.62 | 0.87 | |

| Average by age group 18–23 | 0.56 | 0.82 | |

| Average by age group 24–29 | 0.50 | 0.78 | |

| Average by age group 30–35 | 0.48 | 0.77 |

The CREDI short form includes 20 yes/no items specific to each six-month age group: A = 0–5 months; B = 6–11 months; C = 12–17 months; D = 18–23 months; E = 24–29 months; F = 30–35 months.

Cronbach's alpha suggested adequate internal consistency/inter-item reliability (α > 0.80) for the CREDI within each of the six age groups: 0–5 months (online, α = 0.91, n = 17); 6–11 months (online, α = 0.86, n = 47); 12–17 months (online, α = 0.83, n = 37); 18–23 months (online, α = 0.87, n = 5); 24–29 months (online, α = 0.89, n = 38; in-person, α = 0.83, n = 100); 30–35 months (online, α = 0.87, n = 49; in-person, α = 0.82, n = 492).

The multivariate analyses (Table 3) of the in-person sample showed that a significant proportion of the variance in CREDI scores could be explained by the included predictor variables (R2 = 0.12, p < 0.0001). Similarly, in the online sample, a significant proportion of the variance in CREDI scores could be explained by the included predictor variables (R2 = 0.09, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Results of multivariate regression analyses predicting CREDI scores in the in-person and online samples.

| Outcome | CREDI SF z-score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-person sample | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Child is female | 0.164a | 0.138b | ||||

| (0.077) | (0.0778) | |||||

| Lower than secondary schooling | Ref. group | Ref. group | ||||

| Secondary schooling | −0.005 | −0.0823 | ||||

| (0.081) | (0.0837) | |||||

| Higher education | 0.487c | 0.333a | ||||

| (0.152) | (0.152) | |||||

| Asset quintile (1–5) | 0.098c | 0.0396 | ||||

| (0.029) | (0.0297) | |||||

| Home stimulation score (0–6) | 0.214c | 0.203c | ||||

| (0.027) | (0.0310) | |||||

| Children experiencing stunting (HAZ <−2) | 0.093 | 0.175 | ||||

| (0.201) | (0.169) | |||||

| Observations | 678 | 659 | 600 | 672 | 643 | 553 |

|

R-squared |

0.007 |

0.015 |

0.020 |

0.094 |

0.000 |

0.121 |

| Online sample | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child is female | 0.461c | 0.421c | |||

| (0.079) | (0.082) | ||||

| Lower than secondary schooling | Ref. group | Ref. group | |||

| Secondary schooling | 0.361 | 0.328 | |||

| (0.297) | (0.271) | ||||

| Higher education | 0.370 | 0.285 | |||

| (0.291) | (0.265) | ||||

| Self-reported relative income (1–100) | −0.002 | −0.00290 | |||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | ||||

| Home stimulation score (0–6) | 0.156c | 0.145c | |||

| (0.035) | (0.036) | ||||

| Observations | 587 | 579 | 551 | 587 | 545 |

| R-squared | 0.054 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.035 | 0.089 |

Standard errors shown in parentheses. Height measures were converted into normed HAZ using the World Health Organization Anthro software package. Sample size varies due to differential availability of predictors.

HAZ, height-for-age z-score.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.10.

p < 0.001.

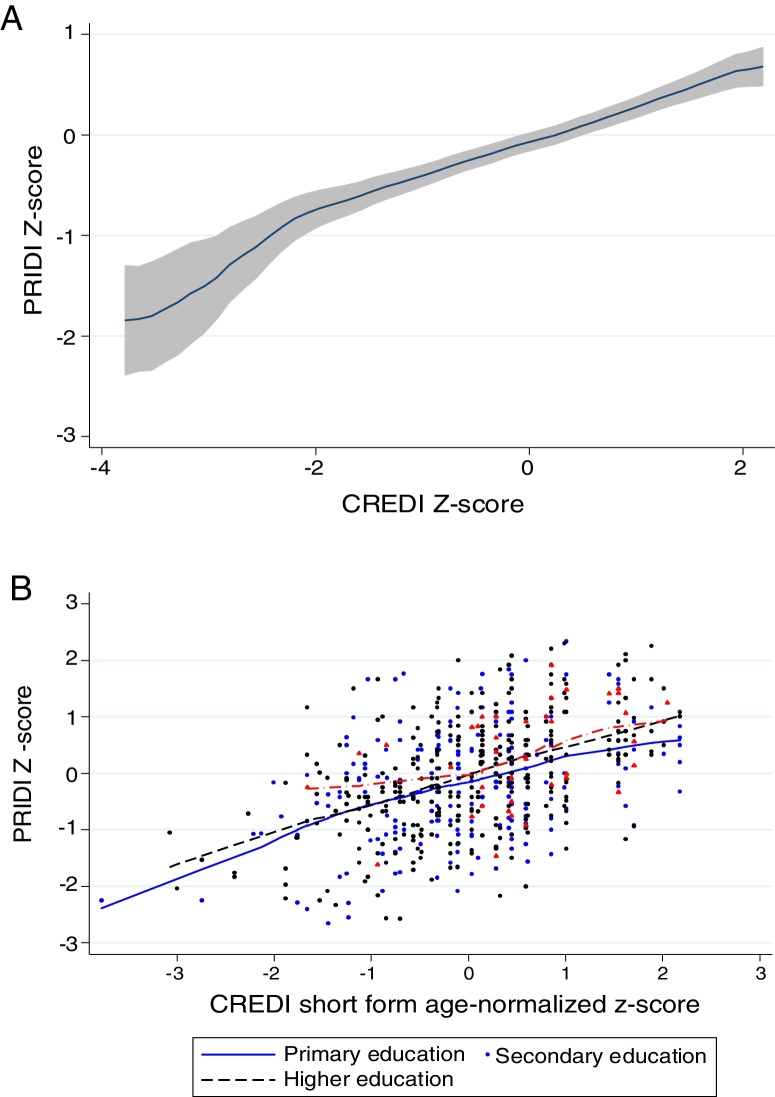

The CREDI scores were moderately correlated with overall PRIDI scores; conditional on age, we found a correlation coefficient of r = 0.46 (p < 0.001) in our in-person sample. Fig. 1A shows a local polynomial curve of normalized PRIDI scores as a function age-normalized CREDI scores along with 95% confidence intervals. Fig. 1B shows the same empirical association between direct observation scores (PRIDI) and CREDI scores by caregiver educational attainment. No statistically significant differences in the observed correlations were found across the three strata of interest (primary, secondary, higher education), suggesting initial evidence for measurement invariance across socioeconomic groups.

Figure 1.

Concurrent validity. (A) Relations between age-normalized caregiver-reported CREDI z-scores and directly assessed PRIDI z-scores. (B) Relations between age-normalized caregiver-reported CREDI z-scores and directly assessed PRIDI z-scores by caregiver education.

Discussion

The CREDI was found to be a highly acceptable tool by both the in-person and online Brazilian samples of caregivers. In both samples, the caregivers did not display any difficulties answering CREDI questions. The qualitative interviews confirmed these findings, with high rates of cognitive understanding across items. The instrument also showed adequate internal consistency across the six age groups. However, the age bands 0–5 months and 18–23 months had few participants and thus need to be further investigated.

Test–retest reliability was moderate to excellent for most of the items, and the rates of agreement were consistently high. The items that showed a low kappa were the most within the socioemotional domain and tended to represent behaviors that are potentially less stable over time and context (e.g. kindness to other children). These findings are consistent with the literature that argues that low kappa values may not necessarily reflect low rates of overall agreement.20 Nevertheless, these findings indicate a need for further exploration of the stability and reliability of caregivers’ reports, particularly in terms of young children's socioemotional skills.

Regarding the construct validity, the findings from the in-person sample showed that children receiving higher CREDI scores tended to be female, have caregivers with higher education, and come from households that were higher in socioeconomic status and stimulation, as expected. In the more geographically diverse and demographically advantaged online sample, on the other hand, the only robust predictor of CREDI scores was the households’ stimulation levels. One reason for the lower levels of discrimination in this sample could be that the sample was more homogenous in terms of education and wealth than the in-person sample, as caregivers were recruited through social media and willing to participate in a written online survey. It is also possible that the more subjective measure of wealth used in this sample introduced error into the estimation, masking true differences. Therefore, the online sample was on average significantly wealthier and better educated than caregivers in the São Paulo sample. However, the home stimulation scores were relatively similar across both samples.

CREDI scores in the in-person sample of children aged 2–3 years also showed adequate concurrent criterion validity with the PRIDI, which uses direct observation of the child to assess early development. These results suggest that caregivers’ reports using a shorter instrument correspond well to a similar population-level assessment from Latin America that uses a more detailed format. Similarly to the CREDI, prior research using the PRIDI has shown that a nurturing environment is associated with child development.9 Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that interventions targeting positive caregiver-child interactions may be effective in closing gaps in child development. Parenting programs that focus on child development and caregiver–child interactions have been shown to be effective within Brazilian samples, highlighting their relevance for future scaling-up.21

Importantly, stimulation practices explained only a relatively small amount of variation in CREDI scores. Given this, comprehensive and multi-faceted programs that directly target children's health, nutrition, and early education are needed alongside programs for families to optimize children's outcomes.22 This basic principle is reflected in Brazil's “Marco Legal da Primeira Infância” legislation.11 The CREDI could therefore be an option for monitoring long-term progress toward this goal, as well as evaluating intervention programs to support child development at a population level.

Furthermore, the CREDI may also be used as a potential indicator for tracking progress toward meeting SDG 4.2. Existing population-level measures of ECD (e.g. ECDI)8 tend to focus on older children only. The CREDI – which was designed explicitly to “bridge” with the ECDI through a set of common items – may therefore serve as a complementary measure of ECD status for the youngest, and potentially most vulnerable children.

Despite the strengths of this study, there are also some limitations that must be addressed through future work. First, our focus on a single geographic context for the in-person sample and the use of a convenience sample in the online survey sample substantially limit the generalizability of these results. Second, it was not possible to use the same socioeconomic measure for the in-person and online samples, precluding direct comparisons between these groups. Finally, the concurrent validity, with direct observation, was performed only for children aged 2–3 years. Future studies should include samples from geographically, linguistically, developmentally, and culturally diverse contexts of Brazil; should utilize alternative approaches to establishing construct validity (e.g. factor analysis); should use similar measures for socioeconomic level; should examine concurrent validity with samples from 0 to 2 years old; and should include the CREDI as an outcome measure in the context of intervention evaluation.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest the CREDI short-form's validity, reliability, and acceptability as a measure of ECD within Brazil. These findings encourage the use of this instrument for large-scale surveys and monitoring efforts of early developmental outcomes in Brazilian children under the age of 3.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding and support provided by the Saving Brains Program from Grand Challenges Canada (Grant Number 0073-03).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Altafim ER, McCoy DC, Brentani A, Escobar AM, Grisi SJ, Fink G. Measuring early childhood development in Brazil: validation of the Caregiver Reported Early Development Instruments (CREDI). J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:66–75.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jped.2018.07.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Shonkoff J.P., Richter L., van der Gaag J., Bhutta Z.A. An integrated scientific framework for child survival and early childhood development. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e460–e472. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black M.M., Walker S.P., Fernald L.C., Andersen C.T., DiGirolamo A.M., Lu C., et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCoy D.C., Black M., Daelmans B., Dua T. Measuring development in children from birth to age 3 at population level. Early Child Matters. 2016;2016:34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denboba A.D., Sayre R.K., Wodon Q.T., Elder L.K., Rawlings L.B., Lombardi J. World Bank; Washington: 2014. Stepping up early childhood development: investing in young children for high returns. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wodon Q. Investing in early childhood development: essential interventions, family contexts, and broader policies. J Hum Dev Capabil. 2016;17:465–476. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raikes A. Measuring child development and learning. Eur J Educ. 2017;52:511–522. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mustard J.F., Young M.E. In: Early child development: from measurement to action: a priority for growth and equity. Young M.E., Richardson L.M., editors. World Bank Publications; Washington: 2007. Measuring child development to leverage ECD policy and investment; pp. 253–292. [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) UNICEF; New York: 2014. The formative years: UNICEF's work on measuring early childhood development. p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdisco A., Cueto S., Thompson J., Neuschmidt O. Interamerican Development Bank; Washington, DC: 2015. Urgency and possibility. First initiative of comparative data on child development in Latin America. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy D.C., Sudfeld C.R., Bellinger D.C., Muhihi A., Ashery G., Weary T.E., et al. Development and validation of an early childhood development scale for use in low-resourced settings. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0122-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasil . Diário Oficial da União, seção 1; 2012. Lei No. 13.257, de 8 de março de 2016. (2016, 9 de março). Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 9 de março de 2016. Dispõe sobre as políticas públicas para a primeira infância e altera a Lei no 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990 (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente), o Decreto-Lei no 3.689, de 3 de outubro de 1941 (Código de Processo Penal), a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT), aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei no 5.452, de 1o de maio de 1943, a Lei no 11.770, de 9 de setembro de 2008, e a Lei no 12.662, de 5 de junho de 2012. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2016/Lei/L13257.htm [cited 12.7.18] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreira R.S., Figueiredo E.M. Instruments of assessment for first two years of life of infant. Rev Bras de Cresc e Desenv Hum. 2013;23:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues O.M. Escalas de desenvolvimento infantil e o uso com bebês. Educ Rev. 2012;28:81–100. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira M.E., Ribeiro F.V., Formiga C. Principais instrumentos de avaliação de desenvolvimento da criança de zero a dois anos de idade. Rev Mov. 2009;2:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filgueiras A., Pires P., Maissonette S., Landeira-Fernandez J. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian-adapted version of the ages and stages questionnaire in public child daycare centers. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:561–576. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio-Codina M., Araujo M.C., Attanasio O., Muñoz P., Grantham-McGregor S. Concurrent validity and feasibility of short tests currently used to measure early childhood development in large scale studies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0160962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filmer D., Pritchett L.H. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh-Manoux A., Marmot M.G., Adler N.E. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med. 2005;67:855–861. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devon H.A., Block M.E., Moyle-Wright P., Ernst D.M., Hayden S.J., Lazzara D.J., et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarship. 2007;39:155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viera A.J., Garrett J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37:360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altafim E.R., Pedro M.E., Linhares M.B. Effectiveness of ACT raising safe kids parenting program in a developing country. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;70:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shonkoff J.P., Fisher P.A. Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:1635–1653. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.