Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the predictive validity of the day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 “quick” PELOD-2 (qPELOD-2) scores for in-hospital mortality in children with sepsis in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of a developing country.

Methods

The data of 516 children diagnosed as sepsis were retrospectively analyzed. The children were divided into survival group and non-survival group, according to the clinical outcome 28 days after admission. Day-1 PELOD-2, day-1 qPELOD-2, pediatric SOFA (pSOFA), and P-MODS were collected and scored. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted, and the efficiency of the day-1 PELOD-2, day-1 qPELOD-2 score, pSOFA, and P-MODS for predicting death were evaluated by the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

Results

The day-1 PELOD-2 score, day-1 qPELOD-2 score, pSOFA, and P-MODS in the non-survivor group were significantly higher than those in the survivor group. ROC curve analysis showed that the AUCs of the day-1 PELOD-2 score, day-1 qPELOD-2 score, pSOFA, and P-MODS for predicting the prognosis of children with sepsis in the PICU were 0.916, 0.802, 0.937, and 0.761, respectively (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Both the day-1 PELOD-2 score and day-1 qPELOD-2 score were effective and able to assess the prognosis of children with sepsis in a PICU of a developing country. Additionally, the day-1 PELOD-2 score was superior to the day-1 qPELOD-2 score. Further studies are needed to verify the usefulness of the day-1 qPELOD-2 score, particularly outside of the PICU.

Keywords: PELOD-2 score, “Quick” PELOD-2 score, Sepsis, Prognosis, Children

Resumo

0bjetivos

A finalidade de nosso estudo foi avaliar a validade preditiva dos escores PELOD-2 no dia 1 e “quick” PELOD-2 no dia 1 com relação à mortalidade hospitalar em crianças com sepse em uma UTIP de um país em desenvolvimento.

Métodos

Foram analisados retrospectivamente os dados de 516 crianças diagnosticadas com sepse. As crianças foram divididas em grupo sobrevida e grupo não sobrevida de acordo com o desfecho clínico de 28 dias após internação. Foram coletadas e pontuadas as variáveis PELOD-2 no dia 1, qPELOD-2 no dia 1, pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA) e Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (P-MODS). A curva da característica de operação do receptor (ROC) foi plotada e a eficiência preditiva do PELOD-2 no dia 1, o escore qPELOD-2 no dia 1, pSOFA, P-MODS com relação a óbito foram avaliados pela área abaixo da curva (AUC) da curva ROC.

Resultados

O escore PELOD-2 no dia 1, escore qPELOD-2 no dia 1, pSOFA e P-MODS no grupo não sobrevida foram significativamente maiores do que os no grupo sobrevida. A análise preditiva da curva ROC mostrou que as AUCs do escore PELOD-2 no dia 1, escore qPELOD-2 no dia 1, pSOFA e P-MODS com relação ao prognóstico de crianças com sepse na UTIP foi 0,916, 0,802, 0,937 e 0,761, respectivamente (todas p < 0,05).

Conclusões

Tanto o escore PELOD-2 no dia 1 e o escore qPELOD-2 no dia 1 foram válidos e conseguiram avaliar o prognóstico de crianças com sepse em uma UTIP de um país em desenvolvimento. Além disso, o escore PELOD-2 no dia 1 foi superior ao escore qPELOD-2 no dia 1. São necessários estudos adicionais para verificar a utilidade do escore qPELOD-2 no dia 1, principalmente fora da UTIP.

Palavras-Chave: Escore PELOD-2, Escore “quick” PELOD-2, Sepse, Prognóstico, Crianças

Introduction

Sepsis is a leading cause of death in adults1 and children.2, 3, 4, 5 In the recent Third International Consensus statement,6 the Sepsis Definitions Task Force defined sepsis as a life-threatening organ dysfunction that occurs due to a deregulated host response to infection, and this definition has aroused heated discussions in the critical medicine field.7 The Sepsis-3 task force has put forth the use of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score to grade organ dysfunction in adult patients with suspected infection. Furthermore, the Sepsis-3 task force has acknowledged that the new criteria are not designed for children and that future studies should consider age-specific physiology and risk stratification.

Leclerc et al.8 performed a secondary analysis of the database used for the development and validation of the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2 (PELOD-2).9 The authors concluded that the PELOD-2 score on day 1 was highly predictive of in-hospital mortality among children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with suspected infection, which suggested its promising use to standardize definitions and diagnostic criteria for pediatric sepsis. Moreover, the authors investigated the predictive performance of a quick Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2 (qPELOD-2) score (Glasgow coma scale <11, tachycardia, and systemic hypotension; Table S1) that was inspired by the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score (altered mentation, tachypnea, and hypotension). The predictive performance of the qPELOD-2 score compared favorably with studies that validated the qSOFA score in adults (area under the curve [AUC]: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.76–0.87).10 The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the predictive validity of day-1 PELOD-2, day-1 qPELOD-2 for in-hospital mortality in children with sepsis in a PICU of a developing country.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of the first Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University in Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province, China from June 1, 2016 to June 1, 2018. Several data were collected retrospectively for the day-1 PELOD-2 score, day-1 qPELOD-2 score, pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA), and Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (P-MODS) calculation. If a variable was measured more than once in the first day, the worst value of the variable was used to calculate the day-1 PELOD-2, day-1 qPELOD-2, pSOFA, and P-MODS. Sex, age, site of infection, length of PICU stay, total hospitalization time, need for mechanical ventilation, duration of ventilatory support, and need for vasoactive drugs were recorded on a data collection form designed for the study.

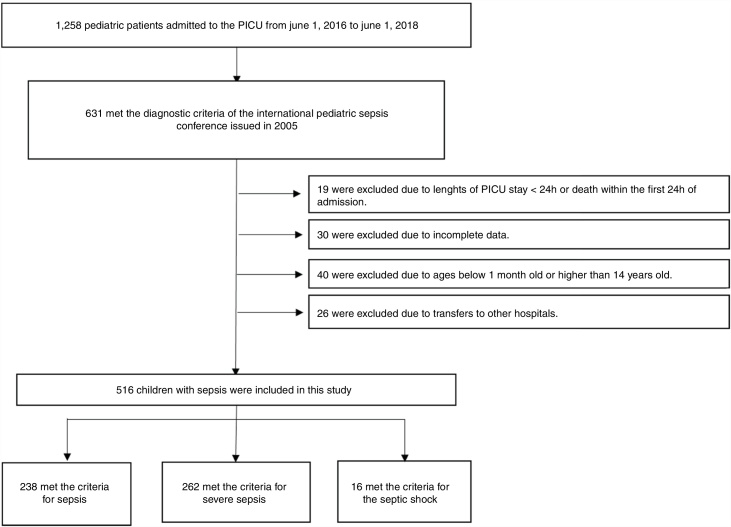

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) meeting the diagnostic criteria of the 2005 International Pediatric Sepsis Conference11 (2) length of PICU stay ≥24 h; (3) patient’s age was between 1 month and 14 years; and (4) complete clinical data available. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) length of PICU stay <24 h or death within the first 24 h of admission; (2) patients younger than 1 month old or older than 14 years old; (3) transfer to another hospital; or (4) incomplete clinical data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic depicting patient screening and enrollment.

This study met the standards of medical ethics and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the first Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (2018-027). The need for an informed consent was waived due to the observational nature of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 and MedCalc 15.2.2. The results were expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the qualitative data. T-tests were used for quantitative data with normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for quantitative data that did not present a normal distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The performance of the scores to discriminate in-hospital mortality was evaluated using the AUC. Comparisons between scores were performed using the DeLong12 methoday-1 to compare AUCs and the Integrated Discrimination Improvement Index13 to evaluate the reclassification of predicted probabilities between survivors and non-survivors. The Youden J statistic14 was used to evaluate the optimal cutoff values of the PELOD-2 and qPELOD-2 scores to discriminate in-hospital mortality.

Sample size estimation

The main evaluation index of this study was the AUC of the ROC curve. We aimed to evaluate the performance of the day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 qPELOD-2 scores to discriminate in-hospital mortality. A related research showed that the AUCs of day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 qPELOD-2 scores were 0.91 and 0.82, respectively.8 The ratio between survivors and non-survivors was 37.15 The significance level was 0.05, the efficacy was 0.8, and the allocation ratio between samples was 50. As the study was a retrospective observational study, the abscission rate was 0%. The sample size was estimated by the software PASS 11.0, and a total of 306 children with sepsis were needed. Finally, 516 children with sepsis in the PICU were included in the study.

Results

A total of 516 patients met the inclusion criteria. Among them, 238 (46.1%) met the criteria for sepsis, 262 (50.8%) met the criteria for severe sepsis, and 16 (3.1%) met the criteria for septic shock. Of the 488 survivors of hospital encounters, 311 (63.7%) were male, and the median (IQR) age was 8 (2–36) months. Among the 28 non-survivors, 16 (57.1%) were male, with a median (IQR) age of 12 (3–36) months. There were no significant differences in sex, age, site of infection, or length of PICU stay between the two groups (all p > 0.05). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the survivors and non-survivors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of survivors and non-survivors.

| Characteristic | Survivors (n = 488) | Non-survivors (n = 28) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, No. (%) | 311 (63.7) | 16 (57.1) | 0.482 |

| Age, median (IQR), Months Site of infection, No. (%) |

8 (2–36) | 12 (3–36) | 0.479 |

| Respiratory system | 280 (57.4) | 11 (39.3) | |

| Nervous system | 72 (14.8) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Digestive system | 43 (8.8) | 2 (7.1) | |

| Blood | 6 (1.2) | 0 | |

| Urinary tract | 13 (2.6) | 0 | |

| Other | 74 (15.2) | 9 (32.1) | |

| Sepsis classification | ≤0.001 | ||

| Sepsis, No. (%) | 238 (49) | 0 (0) | |

| Severe sepsis, No. (%) | 242 (50) | 20 (71) | |

| Septic shock No. (%) | 8 (1) | 8 (29) | |

| Required mechanical Ventilation, No. (%) |

69 (14.1) | 22 (78.6) | ≤0.001 |

| Required vasoactive Infusion on day 1, No. (%) Auxiliary examination |

8 (1.6) | 6 (21.4) | ≤0.001 |

| Glasgow scale [score, median (IQR)] | 13 (11–13) | 7 (4-9) | ≤0.001 |

| PaO2 [mmHg, median (IQR)] | 97 (80–115) | 104 (62–136) | 0.887 |

| PaCO2 [mmHg, median (IQR)] | 30.7 (25.6–35.0) | 27.2 (22.6–38.58) | 0.536 |

| Lactic acid concentration [umol/L, median (IQR)] | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | 2.9 (1.1–10.3) | ≤0.001 |

| Creatinine values [umol/L, median (IQR)] | 22.6 (17.0–31.0) | 30.0 (16.5–55.3) | 0.051 |

| Blood urea nitrogen [mmol/L, median (IQR)] | 3.2 (2.4–4.3) | 4.4 (2.8–6.7) | 0.006 |

| Total bilirubin concentration [umol/L, median (IQR)] | 6.4 (4.6–10.3) | 8.7 (5.9, 19) | 0.04 |

| Fibrinogen concentration [g/L, median (IQR)] | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) | 1.8 (1.2–3.0) | 0.001 |

| White blood cell values [*109/L, median (IQR)] | 13.4 (9.0, 19.0) | 15.4 (9.5, 20.6) | 0.407 |

| Platelet values [*109/L, median (IQR)] | 323 (240, 427) | 292 (211, 388) | 0.132 |

| Scores on day 1 [score, median (IQR)] | |||

| PELOD-2 | 0 (0–2) | 6.5 (4–8) | ≤0.001 |

| qPELOD-2 | 0 (0–1) | 1 (1–2) | ≤0.001 |

| pSOFA | 3 (2–4) | 7.5 (6–11) | ≤0.001 |

| P-MODS | 1 (1–2) | 3 (2–6) | ≤0.001 |

| Outcomes, median (IQR) Duration of ventilatory support, d PICU LOS ≥ 72 h (%) PICU LOS, days |

0 (0–0) 251 (51.4) 1 (1–8) |

2 (1–5) 16 (57.1) 3 (2–6) |

≤0.001 0.698 0.686 |

| Hospital LOS, days | 9 (6–15) | 3 (2–6) | ≤0.001 |

PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; PELOD-2, Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2; qPELOD-2, quick Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2; pSOFA, pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; P-MODS, Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score.

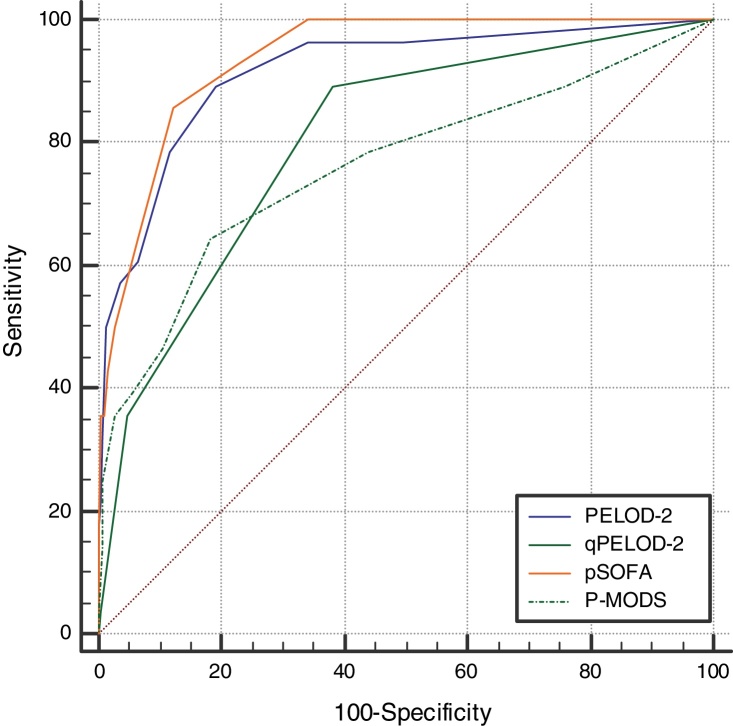

The day-1 PELOD-2 score, day-1 qPELOD-2 score, pSOFA, and P-MODS in the non-survivor group were significantly higher than those in the survivor group (day-1 PELOD-2 score: 6.5 [4–8] vs. 0 [0–2], day-1 qPELOD-2 score: 1 [1–2] vs. 0 [0–1]; pSOFA score: 7.5 [6–11] vs. 3 [2–4]; P-MODS: 3 [2–6] vs. 1 [1–2]; all p < 0.05; Table 1). ROC curve analysis showed that the AUCs of the day-1 PELOD-2 score, day-1 qPELOD-2 score, pSOFA and P-MODS for predicting the prognosis of children with sepsis in the PICU were 0.916 (0.888–0.938), 0.802 (0.765–0.836), 0.937 (0.913–0.957), and 0.761 (0.722–0.798), respectively (all p < 0.05; Table 2; Fig. 2). This indicates that the day-1 PELOD-2 score shows excellent discrimination for in-hospital mortality. The optimal PELOD-2 cutoff to discriminate mortality was a score higher than 2 points. There was no significant difference in the AUC between the day-1 PELOD-2 score and pSOFA (P > 0.05). However, a significant difference was observed in the AUC of the day-1 PELOD-2 score and that of the day-1 qPELOD-2 and P-MODS (both p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Ability of PELOD-2, qPELOD-2, pSOFA and P-MODS to predict the in-hospital mortality.

| Scoring system | AUC | 95% CI | Cutoff | SE (%) | SP (%) | +PV (%) | −PV (%) | Z-score | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PELOD-2 | 0.916 | 0.888–0.938 | >2 | 89 | 81 | 21 | 99 | 14.228 | ≤0.001 |

| qPELOD-2 | 0.802 | 0.765–0.836 | >0 | 89 | 62 | 12 | 99 | 7.905 | ≤0.001 |

| pSOFA | 0.937 | 0.913–0.957 | >5 | 86 | 88 | 29 | 99 | 26.436 | ≤0.001 |

| P-MODS | 0.761 | 0.722–0.798 | >2 | 64 | 82 | 17 | 98 | 4.688 | ≤0.001 |

AUC, area under the curve; SE, sensitivity; SP, specificity; +PV, positive predictive value; −PV, negative predictive value; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PELOD-2, Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2; qPELOD-2, quick Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2; pSOFA, pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; P-MODS, Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of PELOD-2, qPELOD-2, pSOFA, and P-MODS for predicting in-hospital mortality.

Discussion

The 2005 Consensus definition for pediatric sepsis maintained the requirement for SIRS and provided further explanation on organ failure definitions.11 The validity of SIRS criteria to identify and evaluate severity of patients diagnosed with sepsis has been challenged in adults due to the lack of sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP).10, 16 The Sepsis-3 criteria is based on the SOFA score.17 However, the SOFA score is not adapted for children. Therefore, the current pediatric sepsis definitions remain essentially based on Sepsis-2, which is not adequate for clinical research.18 The PELOD-2 score was used to grade organ dysfunction in pediatric patients with suspected infection. Multiple studies have shown that the PELOD-2 score has excellent discrimination for in-hospital mortality.19, 20, 21, 22 The present research demonstrated that day-1 PELOD-2 score shows excellent discrimination for in-hospital mortality in a PICU of a developing country, which suggested its promising use to standardize definitions and diagnostic criteria for pediatric sepsis. Furthermore, the day-1 qPELOD-2 score has good predictive validity for in-hospital mortality (AUC: 0.802; 95% CI: 0.765–0.836). In conclusion, the present study indicates that both day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 qPELOD-2 have good predictive validity for in-hospital mortality in children with sepsis in a PICU of a developing country, which has been seldomly reported.

The SOFA score was developed to evaluate the condition and prognosis of a patient’s illness based on the degree of organ dysfunction. Additionally, the usefulness of the SOFA score has been previously validated in large cohorts of critically ill patients10, 23, 24 Matics and Sanchez-Pinto published a pediatric version of the SOFA score (pSOFA), which was developed by adapting the original SOFA score with age-adjusted cutoffs for the cardiovascular and renal systems and by expanding the respiratory criteria to include noninvasive surrogates of lung injury.15 Those authors concluded that the maximum pSOFA score had excellent predictive validity for in-hospital mortality (AUC: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.92–0.95), but further research was warranted. In the present study, it was concluded that the pSOFA score (AUC: 0.937; 95% CI: 0.913–0.957) is effective and has the ability to assess the prognosis of children with sepsis in a PICU of a developing country, which is conducive to the promotion of pSOFA in developing countries. In the present study, it was observed that the optimal pSOFA cutoff to differentiate in-hospital mortality was a score higher than 5 points, which was different from the cutoff found by Matics and Sanchez-Pinto in children with sepsis in a PICU of a developed country. This observation requires further validation.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective observation study, not enough data was available to allow the daily calculation of all scores daily, which in turn would allow a dynamic assessment of the patients’ condition. Secondly, the relatively small sample size might have resulted in a less precise estimation of the accuracy of day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 qPELOD-2 scores. Thirdly, only children admitted to the PICU were included, and therefore, children at different phases of acute care (out-of-hospital, emergency department, and hospital ward) were not assessed. These limitations reduce the generalizability of the present findings and highlight the need for future prospective multicenter studies.

Both the day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 qPELOD-2 scores are effective and have the ability to assess the prognosis of children with sepsis in the PICU of a developing country. Moreover, the PELOD-2 score is superior to the qPELOD-2 score. Further studies are needed to determine the usefulness of the qPELOD-2 score, particularly outside of the PICU.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study met the standards of medical ethics and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (2018-027). In addition, the need for informed consent was waived due to the observational nature of the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all of the physicians, nurses, and patients of the Children’s Medical Center of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Zhong M, Huang Y, Li T, Xiong L, Lin T, Li M, et al. Day-1 PELOD-2 and day-1 “quick” PELOD-2 scores in children with sepsis in the PICU. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:660–5.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2019.07.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Liu V., Escobar G.J., Greene J.D., Soule J., Whippy A., Angus D.C., et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312:90–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruth A., McCracken C.E., Fortenberry J.D., Hall M., Simon H.K., Hebbar K.B. Pediatric severe sepsis: current trends and outcomes from the Pediatric Health Information Systems database. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:828–838. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuliano J.S., Markovitz B.P., Brierley J., Levin R., Williams G., Lum L.C., et al. Sepsis Prevalence, I. Therapies Study, I. Pediatric Acute Lung and N. Sepsis Investigators. Comparison of pediatric severe sepsis managed in U.S. and European ICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:522–530. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan B., Wong J.J., Sultana R., Koh J., Jit M., Mok Y.H., et al. Global case-fatality rates in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;11:E1–E10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischmann-Struzek C., Goldfarb D.M., Schlattmann P., Schlapbach L.J., Reinhart K., Kissoon N. The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:223–230. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., Shankar-Hari M., Annane D., Bauer M., et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer M. The new sepsis consensus definitions (Sepsis-3): the good, the not-so-bad, and the actually-quite-pretty. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:2027–2029. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4600-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leclerc F., Duhamel A., Deken V., Grandbastien B., Leteurtre S. Can the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score on day 1 be used in clinical criteria for sepsis in children? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:758–763. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leteurtre S., Duhamel A., Salleron J., Grandbastien B., Lacroix J., Leclerc F. PELOD-2: an update of the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1761–1773. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a2bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raith E.P., Udy A.A., Bailey M., McGloughlin S., Mac Isaac C., Bellomo R., et al. New Zealand Intensive Care Society Centre for and E. Resource. Prognostic accuracy of the SOFA score, SIRS criteria, and qSOFA score for in-hospital mortality among adults with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2017;317:290–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein B., Giroir B., Randolph A. International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLong E.R., DeLong D.M., Clarke-Pearson D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pencina M.J., D’Agostino R.B., Sr., D’Agostino R.B., Jr., Vasan R.S. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fluss R., Faraggi D., Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 2005;47:458–472. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matics T.J., Sanchez-Pinto L.N. Adaptation and validation of a pediatric sequential organ failure assessment score and evaluation of the Sepsis-3 definitions in critically ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaukonen K.M., Bailey M., Pilcher D., Cooper D.J., Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1629–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seymour C.W., Liu V.X., Iwashyna T.J., Brunkhorst F.M., Rea T.D., Scherag A., et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:762–774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlapbach L.J. Time for Sepsis-3 in Children? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:805–806. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leteurtre S., Duhamel A., Deken V., Lacroix J., Leclerc F. Daily estimation of the severity of organ dysfunctions in critically ill children by using the PELOD- 2 score. Crit Care. 2015;19:324. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goncalves J.P., Severo M., Rocha C., Jardim J., Mota T., Ribeiro A. Performance of PRISM III and PELOD-2 scores in a pediatric intensive care unit. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:1305–1310. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L., Huang H., Cheng Y., Xu L., Huang X., Pei Y., et al. Predictive value of four pediatric scores of critical illness and mortality on evaluating mortality risk in pediatric critical patients. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2018;30:51–56. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlapbach L.J., Straney L., Bellomo R., MacLaren G., Pilcher D. Prognostic accuracy of age-adapted SOFA, SIRS, PELOD-2, and qSOFA for in-hospital mortality among children with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues-Filho E.M., Fernandes R., Garcez A. SOFA in the first 24 hours as an outcome predictor of acute liver failure. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30:64–70. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20180012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jentzer J.C., Bennett C., Wiley B.M., Murphree D.H., Keegan M.T., Gajic O., et al. Predictive value of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score for mortality in a contemporary cardiac intensive care unit population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:E1–E15. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.