Abstract

Objective

To estimate the accuracy of neck circumference measurement as a method of diagnosing excess weight of six and seven-year-old children.

Methods

1026 six and seven-year-old children were included and anthropometric data were collected using cut-off points for the Body Mass Index (BMI) Z-score, in addition to the measurement of their neck circumference in centimeters. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between neck circumference and BMI. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were calculated. The Receiver Operating Characteristic curve was used to measure the accuracy of neck circumference as a diagnostic method for excess weight.

Results

A positive linear correlation value was observed between neck circumference and BMI 0.572 (p < 0.001). The accuracy value of the global ROC curve was 0.772 (p < 0.001). Sensitivity and specificity showed low values, but high positive predictive values were observed, especially between measures of 30 and 31 cm.

Conclusion

Neck circumference showed accuracy of 77.2% as a diagnostic method for overweightness in six and seven-year-old children.

Keywords: Childhood obesity, Body mass index, Adipose tissue

Introduction

Overweight and obesity are considered a public health issue worldwide. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of overweight or obese individuals in the world almost tripled between 1975 and 2016.1 In Latin America, the estimated number of overweight children is 42.5–51.8 million, representing 20–25% of this population.2 According to the Brazilian Family Budget Survey, 43.8% of girls and 51.4% of boys aged 5–9 years showed overweight.3 In a study made in southern Brazil, the prevalence of overweight was 21.2% and obesity was 12.0% in six-year-old schoolchildren.4

Parameters used in clinical practice for measuring visceral fat are diverse and almost always have some limitations. Gold standard exams, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging5 have a high cost and would make large-scale use unfeasible.6 Abdominal circumference can be difficult to perform or suffer interference from several factors.7 The Body Mass Index (BMI) is considered the most useful measure to be used in the general population,8 but its value does not fully reflect visceral adiposity since it does not distinguish between lean mass and fat, especially in children.9 For children, curves developed by WHO9 are used, with percentiles and Z scores for BMI values. Tracing the design and placing the individual between the curves allows this assessment and in addition to the diagnosis of obesity, the follow-up and evolution of a potential treatment.9

The fat deposited in the upper body segment, as in the neck, seems to release a greater amount of free fatty acids in the plasma and is more similar to visceral fat, being related to insulin resistance and a greater cardiovascular risk.10 In this scenario, the neck circumference can serve as a very useful anthropometric value with few limitations, being easy to perform and low cost, although it is still not used much.10 Some studies in adults have demonstrated a relationship between the measurement of neck circumference and anthropometric indexes used to measure obesity.11, 12 This relationship has also been observed in research involving children.13, 14, 15 The theme has been gaining greater importance in recent years, but literature is still scarce. More research is needed to study this relationship and to confirm its importance that will corroborate in an increased value of neck circumference in obese or overweight children. This investigation contributes to identify the value of a complementary measure to assess children overweight. Therefore, the objective of this investigation was to estimate the accuracy of the measurement of neck circumference as a method of diagnosing excess weight in six and seven-year-old children.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional epidemiological study nested in a cohort called Coorte Brasil Sul.16 The population of this cohort was composed of children born in 2009, living in Palhoça/SC and enrolled in urban and rural public (n = 37) and private (n = 19) schools in 2015. Therefore, the population consisted of six and seven-year-old children. The following parameters were used to calculate the sample: population of 1756 children, expected prevalence of the outcome unknown (p = 50%), confidence level of 95% and relative error of 2%, which generated a minimum sample of 1015 children. Thus, all children registered in the database of the Coorte Brasil Sul,16 with the necessary information for the present study were included (n = 1.026).

Data collection was performed directly at the school by a trained nutritionist from the Coorte Brasil Sul.16

Weight and height data were collected according to the methodology proposed by the Ministry of Health.17 The anthropometric assessment was performed using BMI obtained by dividing weight over squared height, according to the criteria established by the WHO. The cut-off points in the z-score of the BMI were: eutrophy (≥ −2 and <+1), overweight (≥ +1 and <+2) and obesity (≥ +2). Therefore, overweight was considered when the BMI was located in the BMI z-score curves between the values of 1 and 2 (or percentile between 85 and 97) and obesity corresponding to the BMI located on the curve that was above the value 2 (or above the percentile of 97).17

Neck circumference was measured in centimeters using a one millimeter division measuring tape, 205 cm long.18, 19 The child remained upright with their head positioned in the horizontal Frankfurt plane. The upper edge of the measuring tape was positioned just below the cricothyroid cartilage and applied perpendicularly along the neck axis.

Data collected was inserted into Excel spreadsheets and exported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.0 software, where data was analyzed. Sociodemographic variables were described using proportions. The study of the correlation between neck circumference and BMI was performed using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Neck circumference sensitivity and specificity were calculated, in addition to positive and negative predictive values. The use of the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC curve) made it possible to measure the accuracy of the neck circumference as a diagnostic method for excess weight.

The research project was submitted to and approved by the University of Southern Santa Catarina Human Research Ethics Committee under the opinion number 38240114.0.0000.5369. Data were collected after parents signed the consent form provided and children also gave their consent.

Results

Out of the total of 1026 children included in the study, 82.3% (n = 844) studied in public schools and 17.7% (n = 182) in private schools. Males showed a slight predominance over females, with 51.6% (n = 529) male children and 48.4% (n = 497) female. More than half of the participants (64.5%, n = 662) were eutrophic, while the rest were distributed in 18.6% (n = 191) in the overweight range, 9.7% (n = 99) obese and 7.2% (n = 74) seriously obese.

Regarding the neck circumference, the range of values varied between 22.0 cm and 36.5 cm, with an average of 26.7 cm (standard deviation – SD = 2.0). The median and mode values were of 26.5 cm and 26.0 cm, respectively.

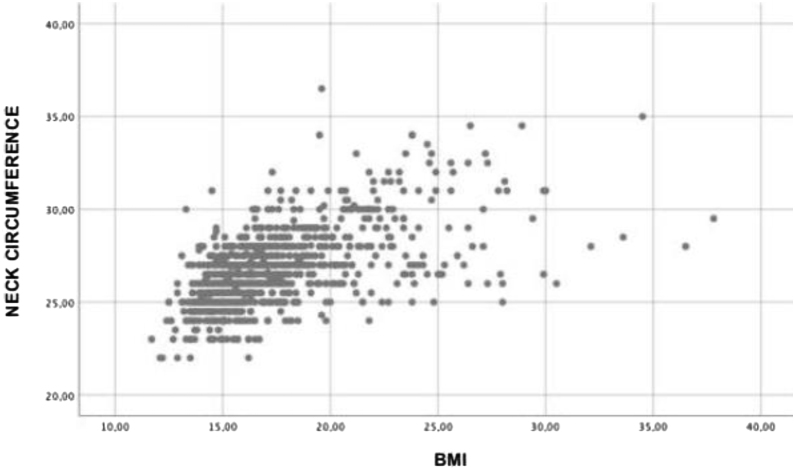

Distribution of neck circumference measurements found according to BMI values are shown in Fig. 1. A positive correlation was observed between neck circumference and BMI of r = 0.572 (p < 0.001) and the coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.327.

Figure 1.

Distribution of neck circumference measurements according to BMI values.

The different values of the neck circumference as well as the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative general and gender predictive values are described in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of neck circumference as a diagnostic method for overweight six- and seven-year-old children in Palhoça/SC (n = 1,026).

| NC (cm) | Se | Sp | PPV | NPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22.0 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.64 |

| 23.0 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.64 |

| 24.0 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.62 |

| 25.0 | 0.09 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.60 |

| 26.0 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.62 |

| 27.0 | 0.23 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.66 |

| 28.0 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 0.51 | 0.67 |

| 29.0 | 0.08 | 0.98 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| 30.0 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.66 |

| 31.0 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| 32.0 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.64 |

| 33.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.35 |

| 34.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.65 |

| 35.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.64 |

| 36.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.64 |

NC, neck circumference; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPP, negative predictive value.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of neck circumference as a diagnostic method of overweight by gender in six and seven-year-old children in Palhoça/SC (n = 1,026).

| Accuracy measures for the male |

Accuracy measures for the female |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC (cm) | Se | Sp | PPV | NPP | NC (cm) | Se | Sp | PPV | NPP |

| 22.0 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 22.0 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.66 |

| 23.0 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 23.0 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

| 24.0 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.60 | 24.0 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.63 |

| 25.0 | 0.09 | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.58 | 25.0 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.61 |

| 26.0 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.22 | 0.58 | 26.0 | 0.22 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.65 |

| 27.0 | 0.23 | 0.75 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 27.0 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| 28.0 | 0.20 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 28.0 | 0.15 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.69 |

| 29.0 | 0.11 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 29.0 | 0.12 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.69 |

| 30.0 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.64 | 30.0 | 0.06 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.68 |

| 31.0 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 31.0 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.67 |

| 32.0 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 32.0 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 |

| 33.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 33.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 |

| 34.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 34.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 |

| 35.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 35.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 36.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 36.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

NC, neck circumference; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPP, negative predictive value.

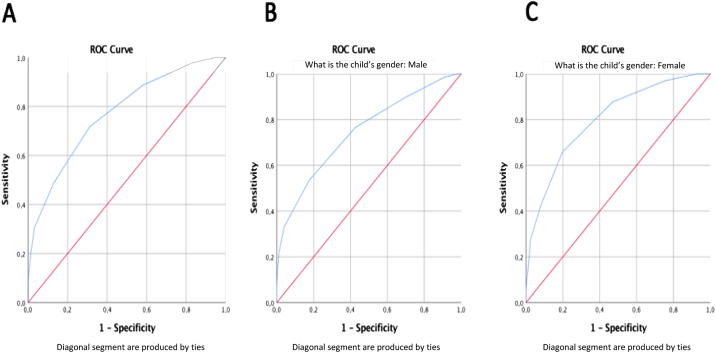

The ROC curves are shown in Fig. 2. Areas under the curves represent the accuracy of the neck circumference as a method of diagnosing overweight. The accuracy value of the global ROC curve was 0.772 (95% Confidence Intervals - CI 0.742; 0.800), p < 0.001 (Fig. 2A). The accuracy for males was 0.746 (95% CI 0.702; 0.790), p < 0.001 (Fig. 2B) and 0.802 (95% CI 0.761; 0.842), p < 0.001 in females (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

ROC curves of the neck circumference as a predictor of obesity for the general population (A), male (B) and female (C).

Discussion

The present study sought to assess whether neck circumference would be a good method of diagnosing excess weight in a pediatric population. Other Brazilian studies have shown that neck circumference can be used as a diagnostic method for obesity in both genders and at different ages in the pediatric group.15, 19, 20

The data showed that there was a moderate positive correlation between the neck circumference and the BMI result corroborated by the literature.15, 20, 21

When comparing the results of sensitivity and specificity, the present study had a low sensitivity, with the highest value being 23% when NC = 27 cm for both genders. For the same age, a study found sensitivity values of 68.8% for males and 62.9% for females,15 while another study21 reached a sensitivity of 80% for males and 83.3% for females. Regarding specificity, the values are high for all the studies analyzed.

A systematic review22 concluded that neck circumference is an accurate measurement to identify overweight and obesity at different ages and genders, especially in adults, women and obese people. However, the age group with less accuracy corresponds to children under 6 years of age, which can be explained by the variability in reliability between evaluators and the rapid growth and development that occur during the first years of life.

Evaluating each neck circumference measured in centimeters, as a diagnostic method of overweight alone resulted in tests demonstrating an accuracy between 74.6% in males and 80.2% in females. This outcome demonstrates the performance of the test to discriminate the presence or not of the result, should the excess weight be determined by neck circumference. The values found in this study correspond to those in the same age group and for both genders in a study performed in Iran, suggesting that NC can accurately identify children with a high BMI.23

The predictive values found were higher than sensitivity and specificity. In fact, predictive values are considered more useful in practice24 as they indicate the probability of the event studied, given the results of a diagnostic test. Thus, the proportion of students with a positive test result who were overweight was 83% and 85% with neck circumference measurements of 29 cm and 31 cm, respectively, in females. In males, positive predictive values of 85% and 93% were obtained at 30 cm and 31 cm of neck circumference, respectively. Hence, it can be said that the higher the BMI, the higher the predictive values found, which is corroborated by the Iranian study.23 However, it is emphasized that for the same test, the higher the prevalence of the event, the greater the positive predictive value and the lower the negative predictive value.24

However, through the correlation analysis a determination coefficient of 32.7% was attained, which means that only about one third of excess weight could be determined by neck circumference. There are still no guidelines in the literature suggesting reference values for this relationship, which makes it difficult to establish parameters.

Some limitations of the present study should be addressed, such as not all students having participated and the fact that measurements were not taken on the same day, which could cause bias. However, a large sample was involved and all care was taken through standardization of collection methods which could minimize any bias.

It can be concluded that, in the population studied, neck circumference proved to be 77.2% accurate as a diagnostic method of overweight in six and seven-year-old children. Sensitivity and specificity showed low values, but high positive predictive values were observed, especially within the measures of 30 and 31 cm. When compared to other methods, neck circumference proved to be a practical and easy to perform low cost method. This work confirmed the results of studies already published on the usefulness of neck circumference for identifying overweight/obesity in children.

Funding

FAPESC/Brazil – Grant 09/2015.

CAPES/Brazil – Financial code 001.

All authors have a registered resume on CNPq’s Lattes platform.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina (UNISUL), Palhoça, SC, Brazil.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO. Obesity and overweight. Geneva: World Health Organization [Cited 19 August 2019]. Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- 2.Rivera J.Á, de Cossío T.G., Pedraza L.S., Aburto T.C., Sánchez T.G., Martorell R. Childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Latin America: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:321–332. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística . IBGE; Brasília: 2009. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008-2009. [Cited 9 April 2020]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/protecao-social/9050-pesquisa-de-orcamentos-familiares.html?=&t=o-quee. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosa L.C., Traebert E., Nunes R.D., Ghizzo Filho J., Traebert J. Relationship between overweight at 6 years of age and socioeconomic conditions at birth, breastfeeding, initial feeding practices and birth weight. Rev Nutr. 2019;32 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micklesfield L.K., Goedecke J.H., Punyanitya M., Wilson K.E., Kelly T.L. Dual- energy X-ray performs as well as clinical computed tomography for the measurement of visceral fat. Obesity. 2012;20:1109–1114. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells J.C., Fewtrell M.S. Measuring body composition. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:612–617. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.085522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshipura K., Muñoz-Torres F., Vergara J., Palacios C., Pérez C.M. Neck circumference may be a better alternative to standard anthropometric measures. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6058916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Report of a WHO Consultation, WHO; 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic.http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_894/en/ [Cited 22 August 2019]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . WHO; 2014. BMI-for-age.http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/bmi_for_age/en/ [Cited 20 September 2019]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papandreou D., Noor Z.T., Rashed M., Jaberi H.A. Association of neck circumference with obesity in female college students. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3:578–581. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2015.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaciragic A., Elezovic M., Babic N., Avdagic N., Dervisevic A., Huskic J. Neck circumference as an indicator of central obesity in healthy young bosnian adults: cross-sectional study. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9:42. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_484_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saka M., Türker P., Ercan A., Kiziltan G., Baş M. Is neck circumference measurement an indicator for abdominal obesity? A pilot study on Turkish Adults. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14:570–575. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i3.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yashoda H.T., Swetha B., Goutham A.S. Neck circumference measurement as a screening tool for obesity in children. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;4:426–430. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelishadi R., Djalalinia S., Motlagh M.E., Rahimi A., Bahreynian M., Arefirad T., et al. Association of neck circumference with general and abdominal obesity in children and adolescents: the weight disorders survey of the CASPIAN-IV study. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nafiu O.O., Burke C., Lee J., Voepel-Lewis T., Malviya S., Tremper K.K. Neck circumference as a screening measure for identifying children with high body mass index. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e306–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traebert J., Lunardelli S.E., Martins L.G., Santos K.D., Nunes R.D., Lunardelli A.N., Traebert E. Methodological description and preliminary results of a cohort study on the influence of the first 1,000 days of life on the children’s future health. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2018;90:3105–3114. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201820170937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica, Coordenação Geral da Política de Alimentação e Nutrição. Incorporação das curvas de crescimento da Organização Mundial de Saúde de 2006 e 2007 no SISVAN. [Cited 10 May 2019]. Available from: http://www.nutricao.saude.gov.br/docs/geral/curvas_oms_2006_2007.pdf.

- 18.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Políticas públicas para o enfrentamento da obesidade infantil no Brasil: seminário de obesidade infantil. [Cited 1 April 2019]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/estrategias_cuidado_doenca_cronica_obesidade_cab38.pdf

- 19.Figueiras M.S., Albuquerque F.M., Castro A.P., Rocha N.P., Milagres L.C., et al. Neck circumference cutoff points to identify excess android fat. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2020;96:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelishadi R., Djalalinia S., Motlagh M.E., Rahimi A., Bahreynian M. Association of neck circumference with general and abdominal obesity in children and adolescents: the weight disorders survey of the CASPIAN-IV study. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondolot M., Horoz D., Poyrazoğlu S., Borlu A., Öztürk A., Kurtoğlu S., et al. Neck circumference to assess obesity in preschool children. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;9:17–23. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroll C., Mastroeni S.S., Czarnobay S.A., Ekwaru J.P., Veugelers P.J., et al. The accuracy of neck circumference for assessing overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hum Biol. 2017;44:667–677. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2017.1390153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taheri M., Kajbaf T.Z., Taheri M.R., Aminzadeh M. Neck circumference as a useful marker for screening overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Oman Med J. 2016;31:170–175. doi: 10.5001/omj.2016.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medronho R., Bloch K.V., Luiz R.R., Werneck G.L., editors. Epidemiologia. Atheneu; São Paulo: 2009. [Google Scholar]