Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility of using ultra-low-dose computed tomography of the chest with iterative reconstruction without anesthesia for assessment of pulmonary diseases in children.

Methods

This prospective study enrolled 86 consecutive pediatric patients (ranging from 1 month to 18 years) that underwent ultra-low-dose computed tomography due to suspicion of pulmonary diseases, without anesthesia and contrast. Parameters used were: 80 kVp; 15–30 mA; acquisition time, 0.5 s; and pitch, 1.375. The adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction technique was used. Subjective visual evaluation and quantitative assessment of image quality were done using a 5-point scale in 12 different structures of the chest.

Results

Mean age was 66 months (interquartile range, 16–147). Final diagnosis was performed in all exams, and 44 (51.2%) were diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, 27 (31.4%) with bronchiolitis obliterans, and 15 (17.4%) with congenital pulmonary airways malformations. Diagnostic quality was achieved in 98.9%, of which 82.6% were considered excellent and 16.3% were slightly blurred but did not interfere with image evaluation. Only one case (1.2%) presented moderate blurring that slightly compromised the image, and previous examinations demonstrated findings compatible with bronchiolitis obliterans. Mean effective radiation dose was 0.39 ± 0.15 mSv. Percentages of images with motion artifacts were 0.3% for cystic fibrosis, 1.3% for bronchiolitis obliterans, and 1.1% for congenital pulmonary airways malformations.

Conclusion

Chest ultra-low-dose computed tomography without sedation or anesthesia delivering a sub-millisievert dose can provide image quality to allow identification of common pulmonary anatomy and diseases.

Keywords: Computed tomography, Thorax, Ultra-low-dose radiation, Iterative reconstruction, Pediatric patients

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar a viabilidade do uso de tomografia computadorizada com ultrabaixa dose com reconstrução iterativa sem anestesia para avaliação de doenças pulmonares em crianças.

Métodos

Este estudo prospectivo envolveu 86 pacientes pediátricos consecutivos (um mês a 18 anos) submetidos à tomografia computadorizada com ultrabaixa dose por suspeita de doenças pulmonares, sem anestesia e contraste. Os parâmetros utilizados foram: 80 kVp; 15-30 mA; tempo de aquisição, 0,5 s; e pitch de 1,375. Foi utilizada a técnica de reconstrução estatística adaptativa iterativa. A avaliação visual subjetiva e a avaliação quantitativa da qualidade da imagem foram feitas com uma escala de 5 pontos em 12 estruturas do tórax.

Resultados

A média de idade foi de 66 meses (intervalo interquartil, 16-147). O diagnóstico final foi feito em todos os exames e 44 (51,2%) foram diagnosticados com fibrose cística, 27 (31,4%) com bronquiolite obliterante e 15 (17,4%) com malformação congênita pulmonar das vias aéreas. A qualidade diagnóstica foi alcançada em 98,9% dos casos, dos quais 82,6% foram considerados excelentes e 16,3% alteração leve na definição, mas isso não interferiu na avaliação da imagem. Apenas um caso (1,2%) apresentou alteração moderada na definição, comprometeu discretamente a imagem, e exames prévios demonstraram achados compatíveis com bronquiolite obliterante. A dose de radiação média efetiva foi de 0,39 ± 0,15 mSv. As porcentagens de imagens com artefatos de movimento foram de 0,3% para fibrose cística, 1,3% para bronquiolite obliterante e 1,1% para malformação congênita pulmonar das vias aéreas.

Conclusão

É possível realizar a tomografia computadorizada com ultrabaixa dose torácica sem sedação ou anestesia, administrando uma dose de submilisievert, com qualidade de imagem suficiente para a identificação pulmonar anatômica e de doenças pulmonares comuns.

Palavras-chave: Tomografia computadorizada, Tórax, Radiação de dose ultrabaixa, Reconstrução iterativa, Pacientes pediátricos

Introduction

In the United States, approximately four to seven million CT scans are performed on children per year.1 However, ionizing radiation still represents a major concern. Radiation dose is extremely important in children, as they are more likely to develop radiation-induced carcinogenesis due to their greater post-exposure life expectancy and more sensitive organs to the oncogenic effects of radiation.2 A cohort study demonstrated that patients submitted to cumulative doses higher than 50 mGy and 60 mGy had a three-fold higher risk of leukemia and brain cancer, respectively.3 For this reason, the radiology community has been looking for strategies to reduce radiation exposure without decreasing image quality, following principles such as “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA).4 One of these strategies includes the use of reconstruction techniques.5

Another common concern in pediatric imaging is sedation/general anesthesia (GA). Young children frequently have difficulty remaining still for the duration of the examination, leading to poor study quality and increasing the likelihood of diagnostic errors. However, sedation is associated with potential adverse effects, mainly due to drug-induced depression of consciousness, with a potential loss of protective reflexes.6 In addition to the acute events, GA has been also linked to long-lasting neurotoxic effects. Studies in children younger than 3 years who underwent GA have demonstrated that some sedation drugs can be associated with long-lasting functional neurotoxic effects, such as memory impairment and increased risk for developmental and behavioral disorders.7, 8, 9, 10

Few studies have assessed potential applicability of reconstruction techniques, such as adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction (ASIR), for pediatric chest CT, and all have used general anesthesia to reduce motion artifacts.11, 12, 13 Due to the cumulative risk of radiation dose, children with chronic lung disease, when subjected to many CT scan during their lifetime, may be at increased risk of carcinogenesis and adverse reactions from sedation. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of using ultra-low-dose CT (ULDCT) with iterative reconstruction without sedation and without contrast in children to evaluate pulmonary diseases.

Materials and methods

Participants

With the approval of the institutional review board, this prospective study included data from 86 consecutive patients between January 2016 and October 2017. Written consent was acquired from the person legally responsible for the patient. Inclusion criteria were patients between 1 month and 18 years undergoing ULDCT of the chest with ASIR for suspect of chronic pulmonary diseases. Exclusion criteria were patients with suspect of interstitial lung disease (ILD), because the ULDCT protocol presents great limitation in the assessment of ILD.14 All study subjects were from the outpatient clinic with elective indication to perform the CT scan. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

CT protocols

All images were obtained with the patient in supine position, using a 16-row multi-detector CT scanner (Lightspeed; General Electric Healthcare – Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States). Parameters utilized were: 80 kVp; acquisition time, 0.5 s; and pitch, 1.375. The chosen current varied from 15 mAs to 30 mAs according to patient size and weight: 1 month–2 years, 15 mAs; 2–4 years, 20 mAs; 4–12 years, 25 mAs; and >12 years, 30 mAs. Images were acquired using a slice thickness of 1 mm. Only inspiration acquisitions were obtained, without expiration techniques. Reconstructions were performed in the axial and coronal planes, with ASIR (100%; General Electric Healthcare – Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States), using a soft kernel.

Radiation doses delivered during CT scans were collected from patient protocols. Dose–length products (DLP) were recorded for each patient. Effective radiation dose (ED) was estimated by multiplying DLP and specific coefficients according to age for chest CT determined by the International Commission on Radiological Protection.15

All exams were performed without any type of sedation. In addition, no intravenous contrast agent was used for this study. Although it was decided to use only non-contrast protocols, patients with suspicion of congenital pulmonary airway malformations (CPAM) in the initial ULDCT scan underwent further CT angiography (CTA) to evaluate the possibility of co-existence of pulmonary sequestration.

Assessment of image quality

All examinations were analyzed with an Advantage Workstation 4.2 (General Electric Healthcare Technologies Waukesha, Wisconsin, United States), using the Picture Archiving Communication System ([PACS]; PixView Star; INFINITT Healthcare Co. Ltd. – Seoul, South Korea). Motion artifact was measured for each image by both radiologists and was classified as yes or no and described in percentage compared to all exams.

Image noise was defined as a standard deviation (SD) of attenuation measured in the air of the tracheal lumen above the aortic arch. Attenuation was measured by one investigator. The region of interest (ROI) was measured in the tracheal lumen above the aortic arch, and size and location of ROIs were kept constant during all series. SD was calculated three times and the median value was used for analysis.

Image quality evaluation was independently performed by two chest radiologists (with 15 and 5 years of experience, respectively) with training in thoracic radiology and blinded to clinical data. The evaluators were from different institutions to where the scans were performed to avoid previous contact with the images and avoid bias. Quality was assessed by reference to normal pulmonary structures and varied lung lesions. Subjective visual evaluation consisted on whether visualization was possible for the following twelve thoracic structures: (1) trachea and primary bronchi, (2) paratracheal lymph nodes, (3) subcarinal lymph nodes, (4) right upper lobe bronchus, (5) middle lobe bronchus, (6) right lower lobe bronchus, (7) left upper lobe bronchus, (8) left lower lobe bronchus, (9) apical segments, (10) medial basal segments, (11) aortic artery, and (12) pulmonary artery. It was decided to include mediastinal lymph nodes as reference structures based on the results from a previous study that demonstrated good accuracy in the detection of mediastinal lymph nodes in non-contrast scans in children.16

Quantitative evaluation of image quality of normal lung structures was evaluated on a 5-point scale: 1 = excellent image quality without artifacts; 2 = mild blurring not interfering with image evaluation; 3 = moderate blurring slightly compromising image evaluation; 4 = severe blurring compromising image evaluation; 5 = low image quality due to presence of artifacts compromising the diagnosis. Scores of 1 and 2 represented diagnostic quality. The quantitative evaluation was done at five different bronchi and vessels generations: (a) major airways, including primary bronchi and intermediate; (b) segmental bronchi and vessels; (c) subsegmental bronchi and vessels; (d) sub-subsegmental vessels; and (e) pleura and subpleural space. A non-diagnostic quality scan was defined as presence of two or more images with a score 3–5 for each of these analyzed tissues. When the scan was considered as non-diagnostic quality, the radiologists would review previous CT scans to reach final diagnosis. The scores were summed, and the images were classified according to the pre-established cut-off points (24–25 points = score 1; 20–23 points = score 2; 15–19 = score 3; 10–14 points = score 4; 5–9 points = score 5).

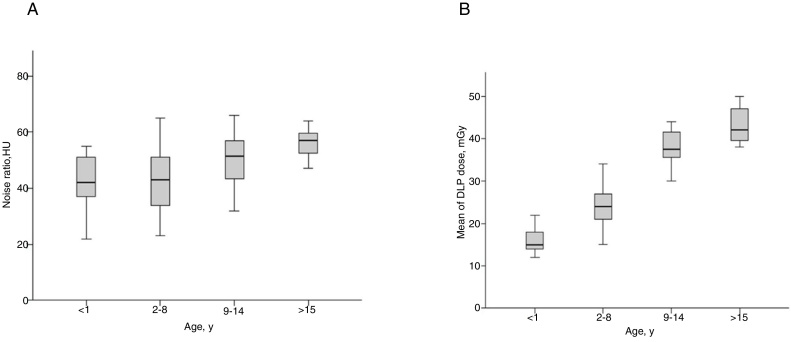

Noise ratio and DLP was stratified by age according to the cutoff previously established in the literature (1 year or less; 2–8 years; 8–14 years; 15 years or more).17

Statistical analysis

Data analysis included descriptive statistics. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess data distribution. Analyses were performed using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and proportions for nominal data. Continuous variables were compared using the independent Student's t-test, whereas Fisher's exact test was used for nominal variables. Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 22, Chicago, USA) and Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA).

Results

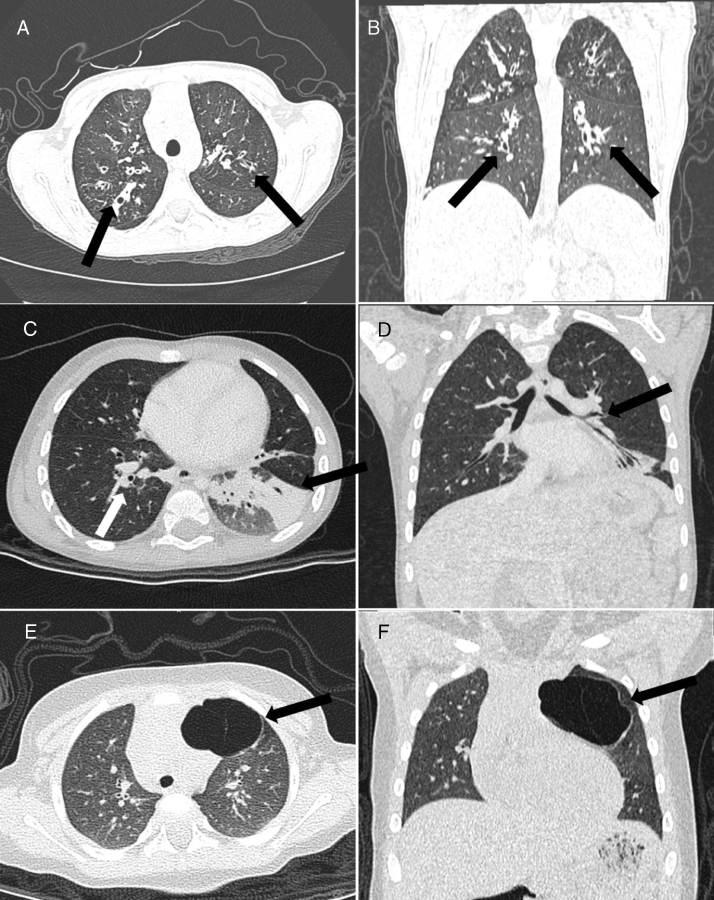

The study sample consisted of 86 patients (female, n = 47; 54.7%) with a mean age of 66 months (IQR, 16–147). Most were from 2 to 8 years (34.8%) or ≤1 year (29%) (Table 1). Only three diseases were founded in this study. Cystic fibrosis (CF) was diagnosed in 44 (51.2%) (Fig. 1A and B), bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) in 27 (31.4%) (Fig. 1C and D), and CPAM in 15 (17.4%) (Fig. 1E and F). All subjects with suspicion of CPAM underwent CTA and concomitant pulmonary sequestration was diagnosed in two (15.3%) cases.

Table 1.

Subjects’ characteristics, CT visual and quantitative analyses, and final diagnoses.

| Parameters | n = 86 |

|---|---|

| Female | 47 (54.7) |

| Age (months) | 66 (16–147) |

| Age groups (years) | |

| ≤1 | 25 (29) |

| 2–8 | 30 (34.8) |

| 9–14 | 16 (18.6) |

| ≥15 | 15 (15.6) |

| Noise ratio, mean ± SD (HU) | 45.5 ± 12.4 |

| Percentage of images with motion artifact, median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.0–2.9) |

| ED, mean ± SD (mSv) | 0.39 ± 0.15 |

| Structure identification, n (% | |

| Trachea and primary bronchi | 86 (100) |

| Paratracheal lymph nodes | 84 (97.7) |

| Subcarinal lymph nodes | 86 (100) |

| Right upper lobe bronchus | 86 (100) |

| Middle lobe bronchus | 85 (98.8) |

| Right lower lobe bronchus | 86 (100) |

| Left upper lobe bronchus | 86 (100) |

| Left lower lobe bronchus | 86 (100) |

| Apical segments | 84 (97.7) |

| Medial basal segment | 84 (97.7) |

| Aortic artery | 86 (100) |

| Pulmonary artery | 86 (100) |

| Image quality score | |

| 1 | 71 (82.6) |

| 2 | 14 (16.3) |

| 3 | 1 (1.2) |

| 4 | – |

| 5 | – |

| Final diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 44 (51.2) |

| Bronchiolitis obliterans | 27 (31.4) |

| Congenital pulmonary airway malformations | 15 (17.4) |

CT, computed tomography; ED, effective dose; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Figure 1.

Male, 8-year-old. Axial (A) and coronal (B) ultra-low-dose CT images demonstrated perihilar (central) cylindrical bronchiectasis (arrows), suggestive of cystic fibrosis. (C) Axial and coronal (D) ultra-low-dose CT images showed a case of a 3-year-old male with bronchial wall thickening (white arrow) and atelectasis in the left lower lobe (black arrow), suggestive of bronchiolitis obliterans. Axial (E) and coronal (F) ultra-low-dose CT images demonstrated a case of type I congenital pulmonary airway malformation in the left upper lobe (arrow) – adenomatous cystic pulmonary malformation – in a 5-year-old female.

Mean effective radiation dose was 0.39 ± 0.15 mSv. Median image noise was 45.5 ± 12.4 HU. Median percentage of images with motion artifacts was 0.8% (IQR, 0.0 – 1.0%). Data on subjective and quantitative evaluations are described in Table 1. Visualization of all the 12 structures analyzed in the subjective visual evaluation was possible in almost all cases. Paratracheal lymph nodes, apical segments, and medial basal segments could not be visualized in two subjects (2.3%), and the middle lobe bronchus in one patient (1.2%). In the quantitative evaluation of image quality, scans presented excellent quality (score 1) in 82.6%, and diagnostic quality (scores 1 or 2) in 98.9%. Only one case (1.2%), a 4-year old male, presented moderate blurring that slightly compromised the image (score 3), and previous examinations demonstrated findings compatible with BO.

When analyzing the median noise ratio separately by age range, there was no significant difference between the groups (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, median DLPs were higher according to higher age ranges (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Median noise ratio index according to age; (B) median dose–length product according to the age cutoffs.

In the secondary analysis separating the subjects according to final diagnosis, there was no difference in the mean noise ratio between the pathologies (p = 0.612). On the other hand, there were statistically significant differences for median percentage of motion artifacts (p < 0.001) and mean ED (p = 0.009). Scans of patients with CF had higher mean ED and lower percentage of images with motion artifacts. Table 2 summarized variables according to final diagnoses.

Table 2.

CT visual and quantitative analyses according to the final diagnoses.

| Variables | CF (n = 44) | BO (n = 27) | CPAM (n = 15) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noise ratio, mean ± SD (HU) | 46.6 ± 13.6 | 45.4 ± 11.3 | 42.9 ± 10.7 | 0.612 |

| Percentage of images with motion artifact, median (IQR) (%) | 0.3 (0–1) | 1.3 (0.8–3.8) | 1.1 (0.4–7) | <0.001 |

| ED, mean ± SD (mSv) | 0.43 ± 0.17 | 0.34 ± 0.012 | 0.3 ± 0.11 | 0.009 |

| Structures identification, n (%) | ||||

| Trachea and primary bronchi | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Paratracheal lymph node | 42 (95.5) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | 0.376 |

| Subcarinal lymph node | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Right upper lobe bronchus | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Middle lobe bronchus | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 14 (93.3) | 0.091 |

| Right lower lobe bronchus | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Left upper lobe bronchus | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Left lower lobe bronchus | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Apical segment | 43 (97.7) | 26 (96.3) | 15 (100) | 0.747 |

| Medial basal segment | 44 (100) | 26 (96.3) | 14 (93.3) | 0.284 |

| Aortic artery | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Pulmonary artery | 44 (100) | 27 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Image quality score, n (%) | 0.666 | |||

| 1 | 37 (84.1) | 22 (81.5) | 12 (80.0) | – |

| 2 | 7 (15.9) | 4 (14.8) | 3 (20.0) | – |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

BO, bronchiolitis obliterans; CF, cystic fibrosis; CPAM, congenital pulmonary airway malformations; CT, computed tomography; ED, effective dose; IQR, interquartile range.

Discussion

This study evaluated the diagnostic performance of ULDCT without anesthesia for pulmonary diseases in children. The authors describe CT images with diagnostic quality in most cases combined with an important reduction in radiation doses. In addition, these results demonstrated the feasibility of scans without sedation, with a low percentage of motion artifacts and image noise. Only one patient had a poor image quality due to intense dyspnea, for whom review of retrospective examinations revealed a possible diagnosis of BO. The noise ratio was similar between the age ranges, showing that it is feasible to avoid sedation use for chest CT scans in children.

Unnecessary exposure to radiation is always a concern, especially in children. This study found an average ULDCT dose–length product of 27.5 ± 11.1 mGy cm, representing an estimated mean ED of 0.39 ± 0.15 mSv. EDs generally are a reflex of the CT protocols chosen, and by using low tube currents (15–30 mAs), tube voltage of 80 kV, and pitch of 1.375, it was possible to deliver such low ED. This would be equivalent to around 25 pediatric chest radiographs in posteroanterior (PA) projection or ten using both PA and lateral projections (mean ED for PA, 15.35 μSv; mean ED for PA + lateral, 40.2 μSv).18 Compared to standard chest CT, ULDCT would represent a significant decrease in radiation. Using patient age- and weight-specific chest CT protocols, Huda and Vance found a hyperbolic curve for mean values of ED according to patient weight, starting around 2.2 mSv for neonates, falling to a minimum of 1.5 mSv for a 10-kg infant and increasing again to 4 mSv for a normal-sized adult.19 The mean ED the present study found would represent only 17%, 26%, and 9.75% of these doses, respectively. A Swiss study12 that used a reduced dose protocol demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy for pulmonary nodules using a ULDCT associated to FBP and ASIR reconstruction when compared to conventional and low dose CT. ED was 0.16 ± 0.006 mSv, slightly lower than those of the present study. However, the biggest difference is that all subjects were adult patients, presenting a much smaller rate of motion artifacts.

Reconstruction models, such as ASIR and FBP, allow massive dose reduction while preserving image quality. The potential use of reconstruction techniques image using ASIR for radiation dose reduction in pediatric patients is well established.11, 13 ASIR results in less noise and artifacts, being superior to FBP, as the latter does not consider details such as accurate location of the focus, size and location of detectors, and system noise. When compared with FBP alone, the combination of ASIR and FBP may reduce the effective dose from 8.65 mSv to 4.25 mSv.20 The ULDCT protocol using ASIR 50 percentage for pediatric thorax CT already demonstrated the maintenance of image quality with an important dose of radiation exposure (0.31 ± 0.03 mSv) and good diagnostic accuracy for pulmonary metastasis.21 Even using parameters as low as 80 kVp and 15–30 mAs and high noise ratio, most scans in the present study evidenced great image quality or only mild blurring, allowing diagnosis in 98.9%.

In this study, CT protocols were done without breath hold techniques. Although BO diagnosis is usually associated with air trapping, it was decided to not include expiratory acquisitions as most children would not comply with adequate expiratory techniques without GA. Previous study had demonstrated that air trapping and mosaic attenuation areas are indirect signs of BO in imaging studies, whereas centrilobular nodules would be a more accurate finding for the final diagnosis of BO.22 In addition, air trapping is a common finding identified in up to 60% of normal patients and is overestimated in the diagnosis of pulmonary diseases in children.23 For these reasons, the authors believe that performing protocols without breath hold techniques did not affect the final diagnoses and the results. The most common findings in this study were centrilobular nodules, peri-bronchial thickening, bronchiectasis, mosaic pattern, and atelectasis, which is in accordance with previous literature data.24

GA for pediatric imaging is always a concern. Studies on pediatric imaging demonstrating a low incidence of adverse events (6.6%) for high risk populations, such as ASA 325 (patient with a severe systemic disease that is not life-threatening), after receiving propofol or fentanyl, the most commonly used drugs for sedation.26 On the other hand, a previous review with 923 pediatric patients undergoing radiological imaging in emergency demonstrated a 10% overall incidence of adverse events, with 0.76% major adverse events requiring intervention, such as significant hypoxemia, apnea, and laryngospasm.27 A topic that is currently under discussion is the potential risk of neurotoxicity related to GA. Stratmann et al.,9 in a preclinical study with rats, showed that the animals submitted to tissue injury during anesthesia had similar rates of impaired recognition memory performance as rats that had been anesthetized without tissue injury. Other preclinical studies also demonstrated that some sedation drugs can be associated with neurodevelopment delay.7, 8 A retrospective cohort with more than 10,000 siblings compared children without developmental or behavioral disorders who had or had not undergone surgery when they were younger than 3 years. The risk of being subsequently diagnosed with developmental and behavioral disorders in children who had surgery when they were younger than 3 years was 60% greater than that of a similar group of siblings who did not undergo surgery (HR 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4–1.8).10 On the other hand, a prospective study conducted by Davidson found no evidence that an hour of anesthetic in infancy increases the risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at two years of age compared to the control group.28 New studies are still necessary to demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between the use of general anesthesia in children and long-term cognitive dysfunction. Due to this great dilemma and growing evidence demonstrating the inherent risks of anesthesia,7 none of the present patients underwent sedation scans, and yet it was possible to maintain great image quality with a low rate of motion artifacts.

The use of a 16-row multidetector CT scanner rather than a newer-generation device is a possible limitation of this study. However, the 16-slice is still a widely used scanner worldwide, representing approximately 30%,29 increasing the external validity of this study. Studies with newer-generation scanners are necessary to corroborate the present results using a CT scanner with 16 channels. However, it is reasonable to believe that the results will be even better with advanced equipment due to better quality and faster image acquisition. In addition, the radiation dose could even be lowered using single or dual source 64-detector CT, and 128-, 256-, and 320-detector single source CT. Studies have reported doses as little as 0.93 mSv for pulmonary nodule detection using a second-generation 320-row detector CT scanner.30 Further studies should also investigate the use of such scanners for chest CT imaging in children.

This study has some other limitations. First, all participants were from the outpatient clinic; further studies should also try to assess chest ULDCT for inpatients, with worst clinical conditions. Second, the sample size was from a trained single center. Third, only three pulmonary diseases were founded in this study. Future studies should also assess image quality in other pathologies. Fourth, only the inter-rater reliability of the evaluation scale was tested, not the intra-rater reliability. Another possible limitation is not including patients with suspicion of ILD, due to a major limitation of ULDCT protocol in the assessment of this disease. Finally, all exams were assessed without expiratory technique, reducing the finding of air trapping, although this sign need not necessarily be present to establish the final diagnosis of BO.

In conclusion, the results demonstrated chest ULDCT without sedation or anesthesia is possible to perform, delivering a sub-millisievert radiation dose and maintaining image quality to allow identification of common pulmonary anatomy and diseases.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Dorneles CM, Pacini GS, Zanon M, Altmayer S, Watte G, Barros MC, et al. Ultra-low-dose chest computed tomography without anesthesia in the assessment of pediatric pulmonary diseases. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:92–9.

References

- 1.Pearce M.S. Patterns in paediatric CT use: an international and epidemiological perspective. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55:107–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner D.J., Hall E.J. Computed tomography – an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearce M.S., Salotti J.A., Little M.P., McHugh K., Lee C., Pyo Kim K., et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:499–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCollough C.H., Primak A.N., Braun N., Kofler J., Yu L., Christner J. Strategies for reducing radiation dose in CT. Radiol Clin North Am. 2009;47:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardhanabhuti V., Loader R.J., Mitchell G.R., Riordan R.D., Roobottom C.A. Image quality assessment of standard- and low-dose chest CT using filtered back projection, adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction, and novel model-based iterative reconstruction algorithms. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:545–552. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arlachov Y., Ganatra R.H. Sedation/anaesthesia in paediatric radiology. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e1018–e1031. doi: 10.1259/bjr/28871143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Anesthetics and cognitive impairments in developing children: what is our responsibility? JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:1135–1136. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilder R.T., Flick R.P., Sprung J., Katusic S.K., Barbaresi W.J., Mickelson C., et al. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stratmann G., Lee J., Sall J.W., Lee B.H., Alvi R.S., Shih J., et al. Effect of general anesthesia in infancy on long-term recognition memory in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2275–2287. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ing C.H., DiMaggio C.J., Whitehouse A.J., Hegarty M.K., Sun M., von Ungern-Sternberg B.S., et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after initial childhood anesthetic exposure between ages 3 and 10 years. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26:377–386. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S., Koloa M.K., Shiney-Bhangle A.S., Saini A.S., Gervais D.A., Westra S.J., et al. Radiation dose reduction with hybrid iterative reconstruction for pediatric CT. Radiology. 2012;263:537–546. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neroladaki A., Botsikas D., Boudabbous S., Becker C.D., Montet X. Computed tomography of the chest with model-based iterative reconstruction using a radiation exposure similar to chest X-ray examination: preliminary observations. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:360–366. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haggerty J.E., Smith E.A., Kunisaki S.M., Dillman J.R. CT imaging of congenital lung lesions: effect of iterative reconstruction on diagnostic performance and radiation dose. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45:989–997. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludes C., Schaal M., Labani A., Jeung M.Y., Roy C., Ohana M. Ultra-low dose chest CT: the end of chest radiograph? Presse Med. 2016;45:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Commission on Radiological Protection ICRP Publication 61: annual limits on intake of radionuclides by workers based on the 1990 recommendations. Ann ICRP. 1991;21 Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alves G.R., Marchiori E., Irion K.L., Guimarães M.D., da Cunha C.F., de Souza V.V., et al. Mediastinal lymph nodes and pulmonary nodules in children: MDCT findings in a cohort of healthy subjects. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:35–37. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss K.J., Goske M.J., Towbin A.J., Sengupta D., Callahan M.J., Darge K., et al. Pediatric chest CT diagnostic reference ranges: development and application. Radiology. 2017;284:219–227. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiljunen T., Tietäväinen A., Parviainen T., Viitala A., Kortesniemi M. Organ doses and effective doses in pediatric radiography: patient-dose survey in Finland. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:114–124. doi: 10.1080/02841850802570561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huda W., Vance A. Patient radiation doses from adult and pediatric CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:540–546. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi L.P., Li Y., Tang L., Li Y.L., Li X.T., Cui Y., et al. Evaluation of dose reduction and image quality in chest CT using adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction with the same group of patients. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e906–e911. doi: 10.1259/bjr/66327067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y., Kim Y.K., Lee B.E., Lee S.J., Ryu Y.J., Lee J.H., et al. Ultra-low-dose CT of the thorax using iterative reconstruction: evaluation of image quality and radiation dose reduction. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:1197–1202. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pipavath S.J., Lynch D.A., Cool C., Brown K.K., Newell J.D. Radiologic and pathologic features of bronchiolitis. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:354–363. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka N., Matsumoto T., Miura G., Emoto T., Matsunaga N., Ueda K., et al. Air trapping at CT: high prevalence in asymptomatic subjects with normal pulmonary function. Radiology. 2003;227:776–785. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2273020352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer G.B., Sarria E.E., Mattiello R., Mocelin H.T., Castro-Rodriguez J.A. Post infectious bronchiolitis obliterans in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2010;11:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA physical status classification system. Available from https://www.asahq.org/resources/clinical-information/asa-physical-status-classification-system [accessed 10.07.18].

- 26.Kiringoda R., Thurm A.E., Hirschtritt M.E., Koziol D., Wesley R., Swedo S.E., et al. Risks of propofol sedation/anesthesia for imaging studies in pediatric research: eight years of experience in a clinical research center. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:554–560. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutler K.O., Bush A.J., Godambe S.A., Gilmore B. The use of a pediatric emergency medicine-staffed sedation service during imaging: a retrospective analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson A.J., Disma N., de Graaff J.C., Withington D.E., Dorris L., Bell G., et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at two years of age after general and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:239–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00608-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granata C., Origgi D., Palorini F., Matranga D., Salerno S. Radiation dose from multidetector CT studies in children: results from the first Italian nationwide survey. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45:695–705. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3201-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen M.Y., Shanbhag S.M., Arai A.E. Submillisievert median radiation dose for coronary angiography with a second-generation 320-detector row CT scanner in 107 consecutive patients. Radiology. 2013;267:76–85. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]