Abstract

Background:

Urticaria is a common skin disease characterized by episodes of wheals, and it has a negative effect on patients’ quality of life. Large-scale population-based epidemiological studies of urticaria are scarce in China. The aim of this survey was to determine the prevalence, clinical forms, and risk factors of urticaria in the Chinese population.

Methods:

This survey was conducted in 35 cities from 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities of China. Two to three communities in each city were selected in this investigation. Participants completed questionnaires and received dermatological examinations. We analyzed the prevalence, clinical forms, and risk factors of urticaria.

Results:

In total, 44,875 questionnaires were distributed and 41,041 valid questionnaires were collected (17,563 male and 23,478 female participants). The lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 7.30%, with 8.26% in female and 6.34% in male individuals (P < 0.05). The point prevalence of urticaria was 0.75%, with 0.79% in female and 0.71% in male individuals (P < 0.05). Concomitant angioedema was found in 6.16% of patients. Adults had a higher prevalence of urticaria than adolescents and children. Living in urban areas, exposure to pollutants, an anxious or depressed psychological status, a personal and family history of allergy, thyroid diseases, and Helicobacter pylori infection were associated with a higher prevalence of urticaria. Smoking was correlated with a reduced risk of urticaria.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated that the lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 7.30% and the point prevalence was 0.75% in the Chinese population; women had a higher prevalence of urticaria than men. Various factors were correlated with urticaria.

Keywords: Urticaria, Prevalence, Risk factor, China

Introduction

Urticaria is a common skin disease characterized by episodes of wheals, with or without angioedema. Urticaria typically resolves within 24 h, without scarring.[1] Angioedema usually presents as sudden swelling of the lower dermis and subcutis, which usually resolves in the mucous membranes and can last up to 72 h.[2] In patients with severe urticaria, gastrointestinal and respiratory involvement may occur. Urticaria has a considerable negative effect on the patients’ quality of life. In patients with frequent episodes, the effect is more severe than that of atopic dermatitis, acne, and psoriasis and is comparable to the effect of ischemic heart disease.[3,4]

Urticaria includes acute urticaria and chronic urticaria. Acute urticaria is often associated with viral infection or an acute allergic reaction to foods, medications, or insects.[5] However, the etiology of chronic urticaria is difficult to be identify.[6] Chronic urticaria has various manifestations, including chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria, depending on whether the episodes are triggered by specific stimuli.[7] Chronic spontaneous urticaria is more common than other forms of chronic urticaria.[8] Urticaria is a main reason for consultations with an allergist, dermatologist, or general practitioner in Western countries.[9] In China, dermatologists treat much more patients with urticaria than other specialists. The prevalence of urticaria has been reported in several studies.[9–14] However, large-scale epidemiological studies in the Chinese population are scarce. We carried out a nationwide survey to determine the prevalence, risk factors, and clinical forms of urticaria in China.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Peking University People's Hospital (No. 2017PHB074-01). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Study population

This survey was conducted in 35 cities covering 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities of China. The pre-estimated sample size was approximately 40,000. The sample size in each region was calculated according to the geographic distribution in the National Census 2010. Stratified multistage cluster sampling was adopted. Two to three communities in each city were randomly selected for the investigation. The target population was adults, adolescents, and children >7 years.

Investigators and questionnaires

The investigators were dermatologists from Peking University People's Hospital and local medical college hospitals. They were all trained for this investigation and were required to pass an examination for qualification. Participants were asked to complete questionnaires and undergo a dermatological examination. In the examination, a vertical force was applied on the forearm of participants using a cotton swab to see whether a linear wheal could be elicited. Lifetime prevalence was defined as having at least one episode of urticaria in the participant's lifetime. Point prevalence was defined as having urticaria within 1 week of the investigation. Exposure to pollutants was defined as exposure to dust, smog, chemical fumes, and exhaust gases in the living and working environments. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of urticaria (overall, in male participants, and in female participants) was calculated based on the China Population Composition in 2010.

Statistical analysis

Epidata version 3.1 (Epidata Association, Odense, Denmark) and IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were used for data entry and data analysis. Quantitative data are presented as mean and standard deviation whereas qualitative data are represented as number and percentage. To investigate differences in the distribution of groups with and without urticaria, we performed the Student's t test for quantitative data and the chi-squared test for qualitative data in these two cohorts. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using logistic regression to identify risk factors and protective factors of urticaria. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

In total, 44,875 questionnaires were distributed and 41,041 valid questionnaires were collected (response rate, 91.46%). The study population included 17,563 male participants (42.79%) and 23,478 female participants (57.21%), ranging from 7.0 to 99.0 years of age (mean 33.5 ± 16.3 years).

Prevalence of urticaria

The lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 7.93% (7.30% after age- and sex-standardization). The lifetime prevalence was 6.61% in male individuals (6.34% after standardization) and 8.92% in female ones (8.26% after standardization) (P < 0.05). Concomitant angioedema was found in 6.16% of patients. The lifetime prevalence of urticaria in different regions is shown in [Table 1]. Of all eight regions of China, the eastern coastal region had the highest prevalence (10.21%) and the northwest region had the lowest prevalence (6.40%).

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence of urticaria in eight regions of China.

| Regions | Subjects (n) | Life-time prevalence (%) |

| Northeast | 5448 | 6.52 |

| Northern Coastal | 4421 | 9.52 |

| Eastern Coastal | 3929 | 10.21 |

| Southern Coastal | 5159 | 9.05 |

| Middle Yellow River | 7049 | 7.06 |

| Middle Yangtze River | 6263 | 8.05 |

| Northwest | 2531 | 6.40 |

| Southwest | 6241 | 7.16 |

The point prevalence of urticaria was 0.76% (0.75% after standardization), with 0.69% in male individuals (0.71% after standardization) and 0.82% in female ones (0.79% after standardization). The point prevalence in female participants was significantly higher than in male participants (P < 0.05).

The lifetime prevalence of urticaria in children, adolescents, and adults was 5.17%, 5.60%, and 8.19%, respectively. Adults had a higher prevalence than children and adolescents (P < 0.05); people aged 30 to 39 years showed the highest prevalence (9.01%). The point prevalence in children, adolescents, and adults was 0.35%, 0.44%, and 0.80%, respectively. Again, adults had a higher prevalence than children and adolescents (P < 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Lifetime prevalence and point prevalence of urticaria by age group.

| Age (years) | Life-time prevalence, n (%) | Point prevalence, n (%) |

| 7–11 | 59 (5.17) | 4 (0.35) |

| 12–17 | 154 (5.60) | 12 (0.44) |

| ≥18 | 3042 (8.19) | 297 (0.80) |

| 18–29 | 1689 (8.90) | 146 (0.77) |

| 30–39 | 572 (9.01) | 59 (0.93) |

| 40–49 | 353 (8.40) | 43 (1.02) |

| 50–59 | 216 (6.13) | 22 (0.62) |

| 60–69 | 140 (5.51) | 19 (0.75) |

| ≥70 | 72 (4.62) | 8 (0.51) |

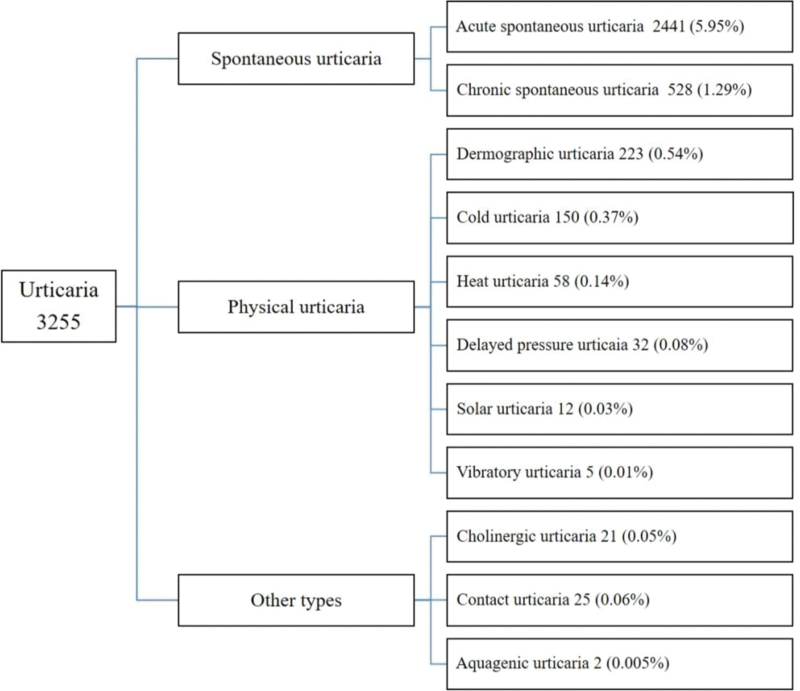

The prevalence of different forms of urticaria is shown in [Figure 1]. Acute spontaneous urticaria was the most common form (5.95%), followed by chronic spontaneous urticaria (1.29%), cold urticaria (0.40%), and dermographism (0.37%). The prevalence of chronic urticaria was 1.80%.

Figure 1.

Lifetime prevalence of different forms of urticaria.

Risk factors and comorbidities of urticaria

Living in urban areas, exposure to pollutants, a psychological status of anxiety and depression, and family history of allergy were associated with a higher prevalence of urticaria; smoking was correlated with a reduced risk of urticaria [Table 3]. Compared with the population without urticaria, a trend toward an increased risk of urticaria was found in patients with eczema (23.78% vs. 13.55%), asthma (2.46% vs. 1.15%), allergic conjunctivitis (2.76% vs. 0.79%), allergic rhinitis (19.39% vs. 9.51%), food allergy (14.53% vs. 4.45%), and drug allergy (11.61% vs. 5.17%) (all P < 0.05). Moreover, thyroid disease (3.20% vs. 1.42%, P < 0.05) and Helicobacter pylori infection (2.58% vs. 1.16%, P < 0.05) were found to be associated with increased risk of urticaria [Table 4].

Table 3.

Selected factors in patients with urticaria and the general population.

| Variables | Urticaria patients (N = 3255) | General population (N = 37,786) | P values |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 ± 39.2 | 21.8 ± 5.4 | 0.417 |

| Location | <0.01 | ||

| Rural | 126 (3.87) | 3263 (8.64) | |

| Urban | 3129 (96.13) | 34,523 (91.36) | |

| Exposure to pollutants∗ | 1053 (32.35) | 9956 (26.35) | <0.01 |

| Smoking history | 329 (10.11) | 4940 (13.07) | <0.01 |

| Drinking history | 182 (5.59) | 2446 (6.47) | 0.127 |

| Pet keeping | 602 (18.49) | 6982 (18.48) | 0.981 |

| Feel nervous or anxious | <0.01 | ||

| Less than once a month | 1158 (35.58) | 16,640 (44.04) | |

| One to three times a month | 1514 (46.51) | 15,729 (41.63) | |

| One to three times a week | 430 (13.21) | 4060 (10.74) | |

| Almost everyday | 153 (4.70) | 1357 (3.59) | |

| Depressed mood | <0.01 | ||

| Less than once a month | 1269 (38.99) | 17,584 (46.54) | |

| One to three times a month | 1567 (48.14) | 15,985 (42.30) | |

| One to three times a week | 320 (9.83) | 3243 (8.58) | |

| Almost everyday | 99 (3.04) | 975 (2.58) | |

| Family history of allergy† | 1255 (38.56) | 6375 (16.87) | <0.01 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). BMI: Body mass index

Defined as exposure to dust, smog, chemical fumes, exhaust gas in the living and working environments.

Defined as allergy history of first-, second-, and third-degree relatives.

Table 4.

Allergic and autoimmune diseases in patients with urticaria n (%).

| Comorbidities | Urticaria patients (N = 3255) | General population (N = 37,786) | P value |

| Eczema | 774 (23.78) | 5119 (13.55) | <0.01 |

| Asthma | 80 (2.46) | 435 (1.15) | <0.01 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 90 (2.76) | 300 (0.79) | <0.01 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 631 (19.39) | 3592 (9.51) | <0.01 |

| Food allergy | 473 (14.53) | 1682 (4.45) | <0.01 |

| Drug allergy | 378 (11.61) | 1953 (5.17) | <0.01 |

| H.pylori infection | 84 (2.58) | 437 (1.16) | <0.01 |

| Thyroid disease | 104 (3.20) | 537 (1.42) | <0.01 |

| Alopecia areata | 15 (0.46) | 164 (0.43) | 0.824 |

| Connective tissue disease∗ | 34 (1.04) | 279 (0.74) | 0.054 |

Connective tissue diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, systemic scleroderma and Sjögren's syndrome, etc.

We loaded 16 variables with a significant univariate relationship into a series of binary logistic regression models. The results showed that female sex (OR = 1.219, 95% CI: 1.121–1.326), living in an urban area (OR = 1.866, 95% CI: 1.552–2.243), exposure to pollutants (OR = 1.172, 95% CI: 1.082–1.270), family history of allergy (OR = 2.311, 95% CI: 2.131–2.507), and having eczema (OR = 1.323, 95% CI: 1.206–1.451), allergic conjunctivitis (OR = 1.769, 95% CI: 1.367–2.289), allergic rhinitis (OR = 1.420, 95% CI: 1.281–1.573), food allergy (OR = 2.574, 95% CI: 2.291–2.891), drug allergy (OR = 1.625, 95% CI: 1.434–1.841), thyroid disease (OR = 1.564, 95% CI: 1.247–1.962), and H. pylori infection (OR = 1.604, 95% CI: 1.252–2.056) were associated with a higher prevalence of urticaria (all P < 0.01). Age (OR = 0.999, 95% CI: 0.996–1.001, P = 0.248), smoking history (OR = 0.939, 95% CI: 0.822–1.072, P = 0.352), frequent anxiety/nervousness (OR = 1.107, 95% CI: 0.993–1.235, P = 0.068), frequent depressed mood (OR = 1.078, 95% CI: 0.969–1.200, P = 0.165), and a history of asthma (OR = 1.131, 95% CI: 0.874–1.465, P = 0.350) had no significant association with urticaria.

Discussion

In this study, we carried out a nationwide population-based survey to investigate the prevalence, clinical forms, and risk factors of urticaria in the Chinese population. The results showed that the lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 7.30% in China. The prevalence of urticaria varied among geographic regions and ethnic groups. One study in Germany reported that the lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 8.8%,[10] whereas another study showed that the cumulative prevalence of urticaria in Germany was 15.4%.[11] A study in Poland reported that the lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 11.2%.[12] Our results were similar to those of the German study but lower than the findings of most other studies.

We found that women had a higher prevalence of urticaria than men (8.26% vs. 6.34%). Several studies have also shown similar results. Lee et al[8] reported that the prevalence of chronic urticaria was significantly higher in female than in male individuals. Another study in Germany also showed a higher cumulative prevalence of urticaria in female than in male participants (16.2% vs. 14.5%).[11] The reason for this sex difference is unknown. The involvement of autoimmunity in the occurrence of urticaria might explain the difference because women are more susceptible than men to autoimmune diseases.[1]

We found that the point prevalence of urticaria was 0.75% in China. The point prevalence was obtained from patients who had urticaria within 1 week of the study. Our results were similar to the studies in Poland (0.70%)[12] and Spain (0.60%)[13] that used the same definition. Again, we found that the point prevalence of urticaria in women was higher than that in men (0.79% vs. 0.71%), which was similar to the study in Spain (0.93% vs. 0.25%).[13] However, the Polish study found no sex differences.[12] In this study, we found that the prevalence of chronic urticaria was 1.80%, which is quite similar to the results of a German study[10] and a Korean study.[14]

The prevalence of chronic spontaneous urticaria was 1.29%, which was lower than a study conducted at Central South University in China (2.70%).[15] In the abovementioned Polish study, the prevalence of chronic spontaneous urticaria was 0.6%.[12] Another study in Europe reported that the 1-year prevalence of chronic spontaneous urticaria in pediatric patients was 0.75%.[16] A study in Italy reported that the 1-year prevalence of chronic spontaneous urticaria increased from 0.02% in 2002 to 0.38% in 2013.[17] Our result was higher than most of these previous studies.

In this study, the prevalence of cold urticaria and dermographism was 0.40% and 0.37%, respectively, whereas the prevalence of other forms of urticaria was lower. A Korean study using an insurance database reported that the prevalence of dermographism, cholinergic urticaria, and cold/heat urticaria was 0.12%, 0.023%, and 0.019%, respectively.[18]

We found that living in an urban area, exposure to air pollutants, anxiety, and depressed mood were associated with a higher prevalence of urticaria, which is similar to that of previous studies. Ding et al[19] reported that air pollution and urbanization were associated with exacerbation of allergic diseases. Patients with urticaria are susceptible to anxiety, depression, and somatoform disorders; and emotional distress can cause aggravation of urticaria.[17] Psychological disorders are not only a consequence of urticaria but also an independent risk factor for urticaria.[20–23] Interestingly, we found a protective effect of smoking, which is similar to a study by Lapi et al.[17] Some studies have reported that nicotine could reduce specific cytokines and thereby modulate immunological responses.[24,25]

Compared with the population that did not have urticaria, allergic diseases other than urticaria were much more common in patients with urticaria, suggesting that these conditions are risk factors of urticaria. Similarly, a German study found that over half of patients with urticaria had concomitant atopic diseases, including allergic rhinitis (41.9%), atopic dermatitis (18.9%), and allergic asthma (17.6%).[10] Another study in children also observed a strong association of urticaria with asthma, eczema, and hay fever.[11] It has been reported that acute urticaria is more common in patients with asthma and could be induced by exacerbation of seasonal asthma.[26] Raciborski et al[12] found that specific foods were important eliciting factors in 12.6% of patients with urticaria. Zuberbier et al[27] reported that immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated food allergy may be a cause of acute urticaria. However, Seitz et al[28] reported that in patients with drug hypersensitivity, potential respiratory viral infection may induce urticaria rather than drugs. It is widely accepted that IgE-mediated hypersensitivity is involved in acute urticaria whereas autoimmunity is predominant in chronic spontaneous urticaria.[29]

We found that thyroid diseases were risk factors for urticaria. It has been reported that 17.7% to 29% of patients with chronic urticaria have anti-thyroperoxidase antibodies, which is higher than that in healthy people (3%–6%). Similar results have also been found for thyroglobulin antibodies and thyroid microsomal antibodies.[30–33] These antibodies may induce inflammation in the thyroid, thereby stimulating cytokine secretion and degranulation of mast cells, which subsequently causes related diseases.[32,34] It has been suggested that thyroid antibody detection and thyroid function screening are of great importance for patients with chronic urticaria.

We found higher rates of H. pylori infection in patients with urticaria, similar to previous studies.[35–37] It has been reported that successful treatment of H. pylori infection can result in the remission of urticaria,[38] highlighting the importance of eradication therapy for H. pylori infection in patients with urticaria.

Female patients with chronic urticaria are more likely to develop autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[29] A study in Brazil showed that childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus was significantly associated with chronic spontaneous urticaria.[39] However, we failed to confirm these findings. Similarly, no correlation was found between alopecia areata and urticaria. We also failed to find a correlation between urticaria and obesity. This is different from the results of many previous studies[40–43] and might be related to the fact that there are fewer obese patients in the Chinese population.

Conclusion

In this nationwide survey, we determined the prevalence and risk factors of urticaria in China. The lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 7.30% and the point prevalence was 0.75% in the Chinese population. Women had a higher prevalence of urticaria than men. A limitation of our study is that most participants were from urban areas and children <7 years old were not included; further studies are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all investigators for their contributions to this study, and all participants for their substantial support.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81442005).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Li J, Mao D, Liu S, Liu P, Tian J, Xue C, Liu X, Qi R, Bai B, Nie J, Ye S, Wang Y, Li Y, Sun Q, Tao J, Guo S, Fang H, Wang J, Mu Q, Liu Q, Ding Y, Zhang J. Epidemiology of urticaria in China: a population-based study. Chin Med J 2022;135:1369–1375. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002172

References

- 1.Fine LM, Bernstein JA. Guideline of chronic urticaria beyond. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2016; 8:396.doi: 10.4168/aair.2016.8.5.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godse K, De A, Zawar V, Shah B, Girdhar M, Rajagopalan M, et al. Consensus statement for the diagnosis and treatment of urticaria: a 2017 update. Indian J Dermatol 2018; 63:2.doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_308_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol 1997; 136:197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14895.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grob JJ, Revuz J, Ortonne JP, Auquier P, Lorette G. Comparative study of the impact of chronic urticaria, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152:289–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westby EP, Lynde C, Sussman G. Chronic urticaria: following practice guidelines. Skin Therapy Lett 2018; 23:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo C, Saltoun C. Urticaria and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc 2019; 40:437–440. doi: 10.2500/aap.2019.40.4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He L, Yi W, Huang X, Long H, Lu Q. Chronic Urticaria: Advances in Understanding of the Disease and Clinical Management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021; 61:424–448. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee N, Lee JD, Lee HY, Kang DR, Ye YM. Epidemiology of chronic urticaria in Korea using the Korean health insurance database, 2010-2014. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2017; 9:438.doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.5.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parisi CA, Ritchie C, Petriz N, Torres CM, Gimenez-Arnau A. Chronic urticaria in a health maintenance organization of Buenos Aires, Argentina - New data that increase global knowledge of this disease. An Bras Dermatol 2018; 93:76–79. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuberbier T, Balke M, Worm M, Edenharter G, Maurer M. Epidemiology of urticaria: a representative cross-sectional population survey. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:869–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brüske I, Standl M, Weidinger S, Klümper C, Hoffmann B, Schaaf B, et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in infants and young children in Germany - results from the German LISAplus and GINIplus Birth Cohort Studies. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014; 25:36–42. doi: 10.1111/pai.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raciborski F, Kłak A, Czarnecka-Operacz M, Jenerowicz D, Sybilski A, Kuna P, et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in Poland - Nationally representative survey results. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2018; 35:67–73. doi: 10.5114/ada.2018.73165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaig P, Olona M, Muñoz Lejarazu D, Caballero MT, Domínguez FJ, Echechipia S, et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2004; 14:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SJ, Ha EK, Jee HM, Lee KS, Lee SW, Kim MA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urticaria with a focus on chronic urticaria in children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2017; 9:212.doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y, Huang X, Jing D, Huang Y, Chen L, Zhang X, et al. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria are associated with parental socioeconomic status in adolescents in China. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99:321–326. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balp MM, Weller K, Carboni V, Chirilov A, Papavassilis C, Severin T, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of chronic spontaneous urticaria in pediatric patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018; 29:630–636. doi: 10.1111/pai.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapi F, Cassano N, Pegoraro V, Cataldo N, Heiman F, Cricelli I, et al. Epidemiology of chronic spontaneous urticaria: results from a nationwide, population-based study in Italy. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174:996–1004. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo JH, Kwon JW. Epidemiology of urticaria including physical urticaria and angioedema in Korea. Korean J Intern Med 2019; 34:418–425. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding G, Ji R, Bao Y. Risk and protective factors for the development of childhood asthma. Paediatr Respir Rev 2015; 16:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conrad R, Geiser F, Haidl G, Hutmacher M, Liedtke R, Wermter F. Relationship between anger and pruritus perception in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22:1062–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbosa F, Freitas J, Barbosa A. Chronic idiopathic urticaria and anxiety symptoms. J Health Psychol 2011; 16:1038–1047. doi: 10.1177/1359105311398682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashiro M, Okumura M. Anxiety, depression, psychosomatic symptoms and autonomic nervous function in patients with chronic urticaria. J Dermatol Sci 1994; 8:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsintsadze N, Beridze L, Tsintsadze N, Krichun Y, Tsivadze N, Tsintsadze M. Psychosomatic aspects in patients with dermatologic diseases. Georgian Med News 2015; 243:70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nizri E, Irony-Tur-Sinai M, Lory O, Orr-Urtreger A, Lavi E, Brenner T. Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory system by nicotine attenuates neuroinflammation via suppression of Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol 2009; 183:6681–6688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra NC, Rir-sima-ah J, Boyd RT, Singh SP, Gundavarapu S, Langley RJ, et al. Nicotine inhibits Fc(RI-induced cysteinyl leukotrienes and cytokine production without affecting mast cell degranulation through alpha 7/alpha 9/alpha 10-nicotinic receptors. J Immunol 2010; 185:588–596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vadasz Z, Kessel A, Hershko AY, Maurer M, Toubi E. Seasonal exacerbation of asthma is frequently associated with recurrent episodes of acute urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2016; 169:263–266. doi: 10.1159/000446183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuberbier T, Iffländer J, Semmler C, Henz BM. Acute urticaria: clinical aspects and therapeutic responsiveness. Acta Derm Venereol 1996; 76:295–297. doi: 10.2340/0001555576295297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seitz CS, Bröcker EB, Trautmann A. Diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity in children and adolescents: discrepancy between physician-based assessment and results of testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2011; 22:405–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Confino-Cohen R, Chodick G, Shalev V, Leshno M, Kimhi O, Goldberg A. Chronic urticaria and autoimmunity: associations found in a large population study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:1307–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan AP, Greaves M. Pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy 2009; 39:777–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cebeci F, Tanrikut A, Topcu E, Onsun N, Kurtulmus N, Uras AR. Association between chronic urticaria and thyroid autoimmunity. Eur J Dermatol 2006; 16:402–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rottem M. Chronic urticaria and autoimmune thyroid disease: is there a link? Autoimmun Rev 2003; 2:69–72. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(02)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turktas I, Gokcora N, Demirsoy S, Cakir N, Onal E. The association of chronic urticaria and angioedema with autoimmune thyroiditis. Int J Dermatol 1997; 36:187–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Donnell BF, Francis DM, Swana GT, Seed PT, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. Thyroid autoimmunity in chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 2005; 153:331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yadav MK, Rishi JP, Nijawan S. Chronic urticaria and Helicobacter pylori. Indian J Med Sci 2008; 62:157–162. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.40579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hellmig S, Troch K, Ott SJ, Schwarz T, Fölsch UR. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in the treatment and outcome of chronic urticaria. Helicobacter 2008; 13:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mogaddam MR, Yazdanbod A, Ardabili NS, Maleki N, Isazadeh S. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori and idiopathic chronic urticaria: effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2015; 1:15–20. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2015.48729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukuda S, Shimoyama T, Umegaki N, Mikami T, Nakano H, Munakata A. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication in the treatment of Japanese patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Gastroenterol 2004; 39:827–830. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferriani MPL, Silva MFC, Pereira RMR, Terreri MT, Saad Magalhães C, Bonfá E, et al. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: a survey of 852 cases of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2015; 167:186–192. doi: 10.1159/000438723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shalom G, Magen E, Babaev M, Tiosano S, Vardy DA, Linder D, et al. Chronic urticaria and the metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional community-based study of 11 261 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32:276–281. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staubach P, Mann C, Peveling-Oberhag A, Lang BM, Augustin M. Epidemiology of urticaria in German children. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2021; 19:1013–1019. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palareti G, Legnani C, Cosmi B, Antonucci E, Erba N, Poli D, et al. Comparison between different d-Dimer cutoff values to assess the individual risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: analysis of results obtained in the DULCIS study. Int J Lab Hematol 2016; 38:42–49. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zbiciak-Nylec M, Wcisło-Dziadecka D, Kasprzyk M, Kulig A, Laszczak J, Noworyta M, et al. Overweight and obesity may play a role in the pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol 2018; 43:525–528. doi: 10.1111/ced.13368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]