Abstract

Geranylgeranyltransferase I (GGTase I) catalyzes the transfer of a prenyl group from geranylgeranyl diphosphate to the carboxy-terminal cysteine of proteins with a motif referred to as a CaaX box (C, cysteine; a, usually aliphatic amino acid; X, usually L). The α and β subunits of GGTase I from Saccharomyces cerevisiae are encoded by RAM2 and CDC43, respectively, and each is essential for viability. We are evaluating GGTase I as a potential target for antimycotic therapy of the related yeast, Candida albicans, which is the major human pathogen for disseminated fungal infections. Recently we cloned CaCDC43, the C. albicans homolog of S. cerevisiae CDC43. To study its role in C. albicans, both alleles were sequentially disrupted in strain CAI4. Null Cacdc43 mutants were viable despite the lack of detectable GGTase I activity but were morphologically abnormal. The subcellular distribution of two GGTase I substrates, Rho1p and Cdc42p, was shifted from the membranous fraction to the cytosolic fraction in the cdc43 mutants, and levels of these two proteins were elevated compared to those in the parent strain. Two compounds that are potent GGTase I inhibitors in vitro but that have poor antifungal activity, J-109,390 and L-269,289, caused similar changes in the distribution and quantity of the substrate. The lethality of an S. cerevisiae cdc43 mutant can be suppressed by simultaneous overexpression of RHO1 and CDC42 on high-copy-number plasmids (Y. Ohya et al., Mol. Biol. Cell 4:1017, 1991; C. A. Trueblood, Y. Ohya, and J. Rine, Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4260, 1993). Prenylation presumably occurs by farnesyltransferase (FTase). We hypothesize that Cdc42p and Rho1p of C. albicans can be prenylated by FTase when GGTase I is absent or limiting and that elevation of these two substrates enables them to compete with FTase substrates for prenylation and thus allows sustained growth.

Isoprenylation is a posttranslational modification that increases the hydrophobicity of proteins, enabling them to associate with membranes, and is sometimes required for function (36, 42). Geranylgeranyltransferase I (GGTase I) and farnesyltransferase (FTase) catalyze very similar reactions and compose one class of prenyltransferases (PTases). GGTase I utilizes the 20-carbon isoprenoid geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) as a substrate, while FTase utilizes the 15-carbon isoprenoid farnesyl diphosphate (FPP). As a result of the action of this class of enzymes, the isoprenoid units are covalently attached to proteins that end in the C-terminal sequence CaaX (C, cysteine; a, aliphatic amino acid [usually]; X, any amino acid) via a thioether linkage to the cysteine residue of the CaaX motif. In general, the X residue of the CaaX sequence determines if the protein is a substrate for GGTase I or FTase (52). After prenylation, the three C-terminal amino acids of the CaaX motif are removed by proteolysis and the free carboxyl group of the prenyl-cysteine is carboxy-methylated (8). GGTase II makes up a second distinct class of PTases and catalyzes geranylgeranylation at both cysteines of C-terminal CC or CXC sequences of Rab proteins (12, 52).

GGTase I and FTase have been extensively characterized biochemically and genetically in the lower eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae (36, 42). Both enzymes are zinc-dependent, magnesium-dependent heterodimers comprising an α and a β subunit. The α subunit is shared by GGTase I and FTase in both yeast and mammals. RAM2 and CDC43 encode the α and β subunits of S. cerevisiae GGTase I, respectively, and each is essential for viability (2, 13, 15, 25, 34). The β subunit of FTase is encoded by RAM1, and null mutants of this gene are temperature sensitive (15, 20). At low temperatures, GGTase I prenylates the requisite FTase substrates and alleviates the requirement for FTase (46).

GGTase I prefers substrates in which X of the CaaX motif is leucine. Typically, GGTase I substrates are small GTP-binding proteins involved in cell polarity, cytokinesis, and morphogenesis (42). Four proteins with CaaL sequences are noted in the S. cerevisiae Yeast Proteasome Database: Rho1p, Rho2p, Cdc42p, and Bud1p. Rho1p and Cdc42p are essential proteins and are the most critical substrates of GGTase I in S. cerevisiae, since the lethality of a cdc43 mutant can be suppressed by simultaneous artificial overexpression of both proteins (35, 46). In this situation, FTase becomes essential and prenylates the required CaaL-containing substrates. Cdc42p is involved in bud positioning and control of cell polarity in S. cerevisiae (2), while Rho1p is important for bud emergence, actin organization, and cell wall integrity (17, 18, 21, 32, 49). Rho1p of both S. cerevisiae and Candida albicans has been shown to be the regulatory subunit of 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase, an essential enzyme involved in cell wall biosynthesis (10, 22, 26, 39).

We are evaluating GGTase I in C. albicans as a potential target for antimycotic therapy. C. albicans is the major opportunistic human fungal pathogen and is the cause of serious systemic disease in immunocompromised patients and of topical infections in healthy individuals (9). S. cerevisiae is frequently studied as a model organism for understanding fundamental processes in C. albicans, a related diploid asexual dimorphic yeast. Rho1p and Cdc42p of C. albicans contain CaaL motifs and are likely GGTase I substrates in vivo (22, 28). Previously, we reported the purification of C. albicans GGTase I and the cloning and sequence analysis of its α and β subunit genes (27). Our work showed that C. albicans GGTase I is also a zinc-dependent, magnesium-dependent heterodimer whose subunits demonstrated 30% amino acid identity with their human counterparts. This relatively low homology suggested the possibility of identifying fungus-specific GGTase I inhibitors.

One important factor regarding the functional requirement for C. albicans GGTase I in vivo is the prenyl acceptor substrate specificity of GGTase I and FTase. We previously showed, using partially purified PTases, that C. albicans GGTase I demonstrated a strong preference for Ras-CaaX substrates in which X of the CaaX motif was a leucine, as was true for both the Saccharomyces and mammalian GGTase I (27). C. albicans FTase demonstrated strong activity with Ras-CVLM, as does S. cerevisiae FTase, and also farnesylated all Ras-CaaL substrates tested at levels ranging from 2 to 20% relative to that observed with Ras-CVLM. Cross-farnesylation of CaaL-containing substrates had been observed before with mammalian and S. cerevisiae FTase (7, 46, 51). Although Saccharomyces FTase can cross-farnesylate CaaL-containing substrates in vitro (7, 46) and has been shown to cross-prenylate in vivo (46), GGTase I of S. cerevisiae is still required for viability. We noted that the magnitude of cross-farnesylation of CaaL-containing substrates observed with C. albicans FTase was higher than had been reported with Saccharomyces FTase (7). Therefore, the requirement for C. albicans GGTase I in vivo was investigated.

Here we report that viable strains with no detectable GGTase I activity were recovered upon sequential disruption of each of the chromosomal homologs containing CaCDC43. We further demonstrate that levels of Cdc42p and Rho1p are elevated in the Cacdc43 mutants as well as in cells treated with GGTase I inhibitors. Our data suggest the existence of a compensatory mechanism that is evoked when GGTase I is absent or limiting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture conditions.

The C. albicans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Uracil-deficient synthetic medium (SD −Ura) has been described previously (44). 5-FOA medium contained 1 mg of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA; Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc.)/ml as described by Boeke et al. (5) with 100 μg of uridine/ml in place of uracil. CMS medium contained 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% yeast extract, 1.0% peptone, 0.1% glucose, and 0.8 M sorbitol. Cultures were routinely grown at 30°C. Growth comparisons of Ura+ prototrophs cultivated in SD −Ura broth were made by determining the A600 at various times. Morphology was assessed by microscopic examination of cells from liquid cultures magnified either 200- or 500-fold with an Optiphot2 inverted microscope (Nikon) and photographed with a Nikon FX-35WA camera.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain | Parental strain | Relevant genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAI4 | SC5314 | CaCDC43a/CaCDC43b | 14 |

| 5 | CAI4 | Cacdc43aΔ::hisG-URA3-hisG/CaCDC43b | This study |

| 5a | 5 | Cacdc43aΔ::hisG/CaCDC43b | This study |

| 5a-1 | 5a | Cacdc43aΔ::hisG/Cacdc43b::URA3 | This study |

| 5a-5 | 5a | Cacdc43aΔ::hisG/Cacdc43b::URA3 | This study |

| 8 | CAI4 | CaCDC43a/Cacdc43bΔ::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| 8a | 8 | CaCDC43a/Cacdc43bΔ::hisG | This study |

| 8a-1 | 8a | Cacdc43a::URA3/Cacdc43bΔ::hisG | This study |

| 8a-2 | 8a | Cacdc43a::URA3/Cacdc43bΔ::hisG | This study |

| Ca-L1 | CAI4 | CaCDC43a/CaCDC43b + pJAM11(URA3)a | 45 |

| MY1055 | Clinical isolate | CaCDC43/CaCDC43 | 1; |

| ATCC 90028 | Clinical isolate | CaCDC42/CaCDC42 | 31 |

Integrated at URA3 locus.

Nucleic acid isolation, hybridization, and sequence analysis.

Plasmid DNA was isolated with Qiagen-tip 500, Qiagen-tip 100, or QIAprep miniprep kits (Qiagen). Genomic DNA from C. albicans was isolated as described by Hoffman and Winston (16) and further purified with GENECLEAN (BIO 101, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The additional purification step was necessary to obtain high-quality DNA from CaCDC43-disrupted strains. Southern blots were performed with Zeta-ProbeGT-derivatized nylon membranes (Bio-Rad) under stringent hybridization and washing conditions. Hybridization was carried out at 65°C for 16 h in 0.5 M Na2HPO4 [pH 7.2]–7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The blots were washed at 65°C twice with 40 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 7.2]–5% SDS and twice with 40 mM Na2HPO4–1% SDS for 30 min per wash. Total RNA was isolated with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center), and mRNA was isolated with a PolyATract mRNA kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. mRNA (2 μg) was subjected to electrophoresis on 1% agarose formaldehyde gels (41) and transferred to Duralon membranes (Stratagene). The blots were hybridized with QuikHyb solution from Stratagene following the manufacturer's recommendations. DNA probes for both the Southern and Northern blots were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP with a PrimeItII random-primed DNA labeling kit (Stratagene). DNA sequence was determined on a model 377A automated DNA sequencer with a Prism Ready Reaction dyedeoxy terminator cycle-sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group software package. Homology searches were performed with the BLAST network service (3).

Cloning of CDC42 and RHO1 genes from C. albicans.

CDC42 and RHO1 were independently cloned by amplification with degenerate oligonucleotides prior to the publications of Mirbod et al. (28) and Kondoh et al. (22), which also describe the cloning of these genes. Genomic fragments with the full coding sequence were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. A 2.4-kb XbaI fragment of Candida DNA containing CDC42 from ATCC 90028 was cloned into pUC19 (50) to construct pMK2. A 617-bp fragment containing RHO1 from strain CA124 (43) was cloned into pCR2 (Invitrogen) to construct pTKRBE.

Gene disruption of CaCDC43.

A plasmid containing a deletion of CaCDC43, pCDC40d, was made by replacing an 875-bp BglII-EcoRV fragment from pCaCDC43-40 (27) with a 4.2-kb BglII-PvuII fragment from pMB7 containing the Ura blaster sequence. The construct was digested with XhoI and XmnI, liberating an ∼5.2-kb fragment containing the Ura blaster region with 440 and 560 bp of flanking Candida DNA. CAI4 was transformed to Ura+ with the disrupted DNA according to a lithium acetate protocol described for S. cerevisiae by Elble (11), and transformants were selected on SD −Ura medium. Counterselection of the URA3 gene was conducted on 5-FOA-containing medium as described by Fonzi and Irwin (14). A second disruption construct, pCDC43d3, was made by ligating the 1.3-kb XbaI-ScaI URA3 fragment from pJAM11 (45) into the BglII site of pCaCDC43-40. Plasmid pCDC43d3 was linearized with XmnI and XhoI, which released a 3.1-kb fragment containing the URA3 gene flanked by 0.44 and 1.4 kb of Candida DNA and was used to transform CDC43-disrupted heterozygotes to Ura+.

Drug treatment of C. albicans.

C. albicans MY1055 was grown overnight in CMS broth, diluted to an A600 of 0.4, and grown to an A600 of 0.6. Compounds dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide were added to the cultures, and control cells were treated with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide. After growth for an additional 2 h, the cultures were harvested and the cell pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer composed of 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim). Cell extracts were prepared and fractionated into P100 and S100 fractions as described in the next section.

Protein extract preparation, fractionation, and partial purification.

Cell extracts of Cacdc43 mutants and Ura+ CDC43-disrupted heterozygotes were prepared from cultures grown overnight in SD −Ura broth and from CAI4 and the 5-FOA-resistant Ura− heterozygotes grown with uridine (100 μg/ml) added to the medium. The following day, the cells were diluted to an A600 of 0.4 and allowed to double before being harvested. An equal volume of chilled lysis buffer containing 50 mM bis-tris propane–HCl [pH 7.0], 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail, and 1 mM Pefabloc protease inhibitor (Boehringer Mannheim) was added to the cell pellet (∼1 g [wet weight]). The cell slurry was homogenized in a Mini-Bead-Beater (Biospec) with 0.5-mm-diameter glass beads eight times for 30 s each time, with intermittent cooling on ice. The crude extract was collected and centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h to produce pellet (P100) and supernatant (S100) fractions. The pellet was resuspended to a volume equal to the supernatant fraction (∼1 ml). GGTase I and FTase were partially purified from S100 fractions (from 200 ml of cell culture) by chromatography on a 1-ml HiTrap Q-Sepharose column (Pharmacia). The S100 fraction (0.7 to 0.8 ml; 6.5 to 10.5 mg/ml) was loaded onto the column equilibrated in 20 mM bis-tris propane–HCl [pH 7.0], 0.02 mM ZnCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2 (buffer A). The column was washed in buffer A and eluted with a 20-ml gradient of NaCl (0 to 0.75 M) in buffer A at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and fractions (0.5 ml) were collected. The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (6) with Coomassie Plus protein assay reagent (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Protein PTase assays.

Protein PTase activities were determined by an acid quench-filtration assay as previously described (27). The conditions for the GGTase I assay were 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, 0.05% dodecyl maltoside, 20 μM Ras-CVIL (or 10 μM CaCdc42p), and 4 μM 3H-GGPP (or 4 μM 3H-FPP as described in the legend to Fig. 4). FTase assays were performed with 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 1 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM ZnCl2, 0.05% dodecyl maltoside, 20 μM Ras-CVLM, and 4 μM 3H-FPP. All reactions were performed in duplicate and were initiated by the addition of PTase activity (2.5 to 5 μl) to a final volume of 25 μl and incubated at 30°C for 30 to 60 min. All other details of the assay and the origin of the Ras substrates were described previously (27).

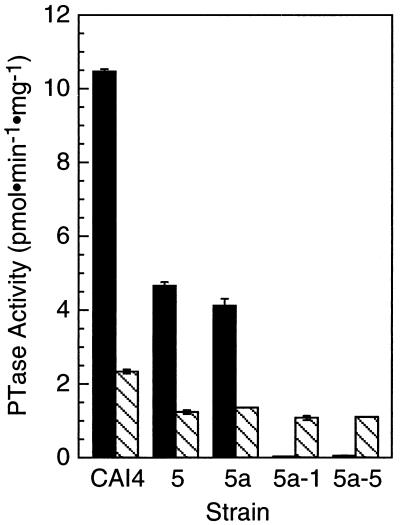

FIG. 4.

PTase specific activity in Cacdc43 null mutants and parent strains. PTase specific activities were determined on S100 fractions as described in Materials and Methods and assayed with Cdc42p substrate (10 μM) as the prenyl acceptor and either GGPP (solid bars) or FPP (hatched bars) at 4 μM as a prenyl donor. The data are averages of duplicate determinations, and the error bars indicate the differences between replicates.

Expression and purification of C. albicans Cdc42p.

Histidine6-CaCdc42p fusion protein was expressed from plasmid pMK11 (T. Satoh, unpublished data) and purified as follows. A 1-liter culture of E. coli BL21(DE3)(pMK11) in Luria broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml was grown at 37°C to an A600 of 0.8. The culture temperature was reduced to 18°C, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the cells were harvested following a 21-h incubation at 18°C. The cell paste (5.4 g [wet weight]) was resuspended in 40 ml of 50 mM Na-phosphate, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 200 mM NaCl, 50 μM GTP (lysis buffer) containing 1 mM Pefabloc protease inhibitor, and 1 mM benzamidine (Sigma). All subsequent steps were performed at 4°C unless otherwise indicated. The cells were lysed by sequential treatment with lysozyme (0.75 mg/ml; 20 min at 25°C), sonication, and DNase (2.5 μg/ml; 20 min). The crude lysate was centrifuged (15,000 × g; 15 min), and the supernatant solution was applied in batch format (20 min with rocking) to Talon metal affinity resin (4 ml; Clontech) equilibrated in lysis buffer. The resin was batch washed twice with lysis buffer (40 ml), transferred to a column, washed with lysis buffer (40 ml) and eluted with lysis buffer containing 100 mM imidazole at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The Talon eluate was pooled (35 ml) and dialyzed overnight against 3 liters of 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]–50 μM GTP. The dialyzed sample contained 37.5 mg of protein estimated as >90% CaCdc42 fusion protein by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The histidine tag was cleaved by digestion overnight with thrombin (Jones Medical Industries) at 16°C (2.5 U of thrombin/mg of fusion protein) and removed by passage over Talon resin. The cleaved CaCdc42p was concentrated on a Centriprep-10 (Amicon) and purified to homogeneity by gel filtration on a Superdex-200 HR 10/30 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated in dialysis buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT. The integrity of the CaCdc42p samples was verified by mass spectroscopic analysis.

Preparation of antisera and Western blot analysis.

Preparation of anti-Rho1p sera will be described elsewhere (T. Satoh, unpublished data). Anti-C. albicans Cdc42p polyclonal antiserum was generated in four rabbits (Covance Research Products) with purified recombinant CaCdc42p as the antigen. The antiserum detected recombinant CaCdc42p and a protein of similar size, ∼21 kDa, in microsomes of C. albicans by Western blotting. A faint band migrating slightly more slowly than Cdc42p was detected and may represent a different, modified form of the protein as suggested by Ziman et al. (53), who have found that antiserum raised against S. cerevisiae Cdc42p recognizes multiple proteins similar in size. Polyclonal antiserum against S. cerevisiae plasma membrane H+ ATPase, Pma1p, was produced in rabbits by using native Pma1p purified from S. cerevisiae microsomes as the antigen (the identity of the purified Pma1p was verified by amino acid sequencing) (P. Mazur and W. Baginsky, unpublished data). In Western blots of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae microsomes, the anti-Pma1p serum cross-reacted with a protein band of similar size (ca. 100 kDa). Protein samples (2.5 to 25 μg) were suspended in Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and separated by electrophoresis on either 12 or 15% precast mini-SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. Anti-Rho1p antibody was reacted at a 1:1,000 dilution followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G secondary antibody at a 1:5,000 dilution. Anti-Cdc42p antibody was used at a dilution of 1:1,000, and anti-Pma1p antibody was used at a 1:10,000 dilution, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:16,000. The antigen-antibody complexes were detected with an ECL chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham) under conditions recommended by the manufacturer.

RESULTS

CaCDC43 is not essential for growth in C. albicans CAI4.

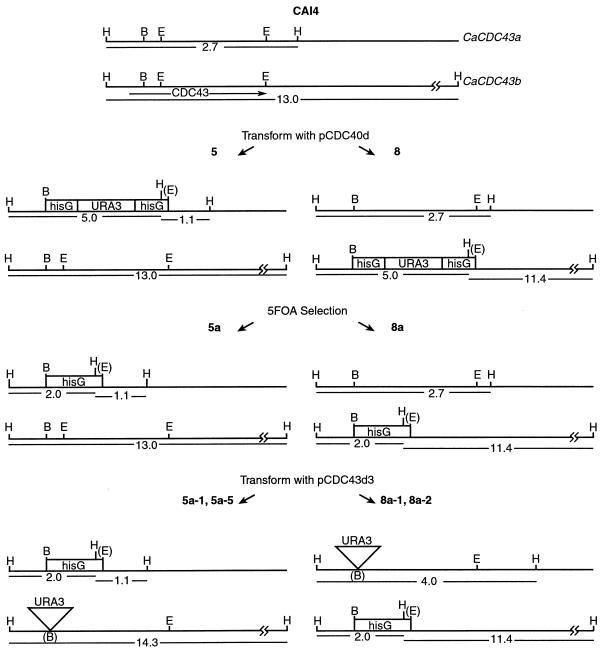

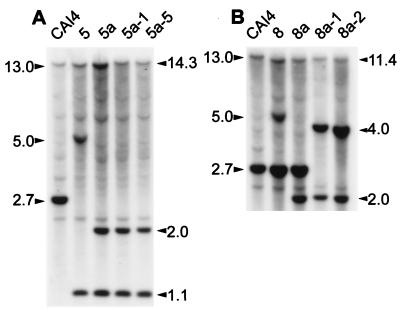

To study the role of Cdc43p in C. albicans, both copies of the CaCDC43 gene were disrupted. A plasmid containing a deletion of CaCDC43 was constructed, and a linear fragment was used to transform CAI4 to Ura prototrophy as described in Materials and Methods. This Ura blaster strategy (14) should result in deletion of ∼60% of the coding sequence of CaCDC43 on one chromosomal homolog. To confirm that a gene replacement occurred, transformants were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. The CaCDC43 locus of CAI4 has an allelic HindIII polymorphism which can be used to distinguish which of the two chromosomal homologs is disrupted. For our purposes, the 2.7-kb HindIII-HindIII fragment produced by digestion of genomic DNA from strain CAI4 defines the CaCDC43a allele and the 13-kb HindIII-HindIII fragment defines the CaCDC43b allele (Fig. 1 and 2). If CaCDC43a is disrupted, the 2.7-kb HindIII fragment will be replaced by novel 5.0- and 1.1-kb fragments, and if the other allele is disrupted, the 13-kb HindIII fragment will be replaced by fragments of 5.0 and 11.4 kb. Transformants in which either of the two alleles is disrupted are diagrammed in Fig. 1, and Southern blotting results are shown in Fig. 2. Transformants 5 and 8 have the a and b alleles disrupted, respectively. As expected, the 5.0-kb fragment in each of the heterozygotes also hybridized to a URA3 probe (data not presented). The appropriate excision of the URA3 gene via recombination between the hisG repeats of the Ura blaster sequence was confirmed by the reduction of the 5.0-kb fragment to 2.0-kb in each of the heterozygotes, as exemplified by transformants 5a and 8a. To inactivate another allele of CaCDC43, another disruption construct was made that contained an insertional inactivation of CaCDC43 with no hisG sequence (described in Materials and Methods). If disruption of CaCDC43 was a lethal event, we expected strong selection for targeted integration to occur in the chromosome that was already disrupted; therefore, a construct that had no sequence bias towards integration at this locus was preferable. Integration of the disrupted plasmid DNA into the undisrupted allele of strain 5a would result in the replacement of the 13.0-kb HindIII fragment with a 14.3-kb fragment, and the 2.0- and 1.1-kb fragments indicative of disruption of CaCDC43 would remain, as exemplified by transformants 5a-1 and 5a-5. A double disruption of strain 8a would contain a 4.0-kb fragment instead of the 2.7-kb fragment; 2.0- and 11.4-kb fragments indicative of the disruption of CaCDC43b would remain, as shown by transformants 8a-1 and 8a-2. All seven transformants of 8a analyzed and 8 of 11 transformants of 5a had a hybridization pattern consistent with disruption of CaCDC43 on both chromosomal homologs.

FIG. 1.

Diagram illustrating construction of Cacdc43 null mutants by sequential gene disruption, starting with strain CAI4 (not drawn to scale). The plasmids are described in Materials and Methods. Relevant HindIII fragments in all of the strains are noted. H, HindIII; B, BglII; E, EcoRV.

FIG. 2.

Autoradiogram of Southern blot hybridization of genomic DNA from C. albicans cdc43 null mutants and parent strains (illustrated in Fig. 1 and described in Table 1). The probe was a radiolabeled 2.7-kb CaCDC43 HindIII fragment.

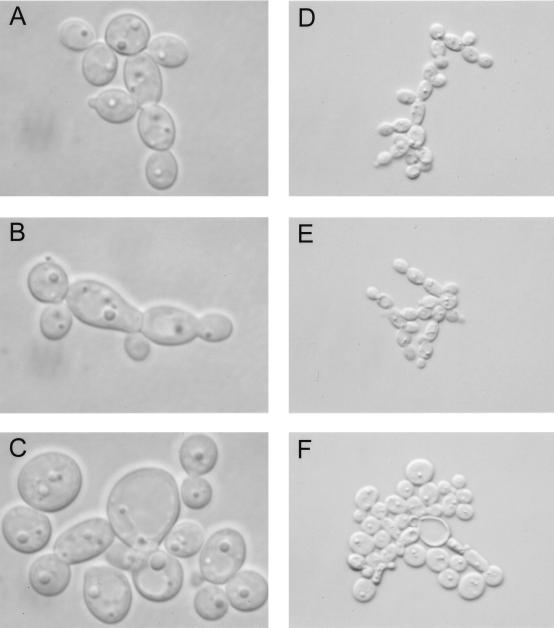

The growth in liquid culture of null mutants 5a-1 and 8a-1 was compared to that of heterozygotes 5 and 8 and a Ura+ transformant of CAI4, Ca-L1. No substantial differences were found until late log phase, when the growth of the null mutants was reduced to ∼70% of that of the CDC43 heterozygote and the wild-type parent strain (data not shown). The morphology of the null mutant cells differed from that of the parent strains several hours before the onset of late-log-phase growth; the mutant cells were rounder and swollen, were substantially clumped, and had significantly fewer buds than the heterozygote or parent strain, as shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Morphologies in mid-log phase of C. albicans Cacdc43 null mutants compared to those of parent strains at high and low magnifications. (A and D) Wild-type Ca-L1; (B and E) CDC43-disrupted heterozygote 5 (C and F) Cacdc43 null mutant 5a-1.

Cacdc43 null mutants are devoid of GGTase I activity.

To confirm that GGTase I activity had been abolished in the cdc43 mutants, cell extracts were prepared from wild-type, CDC43-disrupted heterozygous strains, and the cdc43 null mutants. As shown in Fig. 4, with GGPP and Cdc42p as the prenyl donor and acceptor, respectively, the specific activity of geranylgeranylation from heterozygotes 5 and 5a was approximately 50% of the activity observed for wild-type CAI4. Null cdc43 mutants 5a-1 and 5a-5 had essentially no GGTase I activity. The specific activity of farnesylation of Cdc42p was not increased in these strains, as indicated in Fig. 4. Additional null cdc43 mutants, 8a-1 and 8a-2, were also devoid of GGTase I activity (data not presented). GGTase I activity was measured in the same strains with Ras-CVIL as a prenyl acceptor. The specific activity of geranylgeranylation in the heterozygotes was again approximately half of the value obtained for the wild type. The null cdc43 mutants, 5a-1, 5a-5, 8a-1, and 8a-2, contained approximately 3% of the activity of wild-type cells.

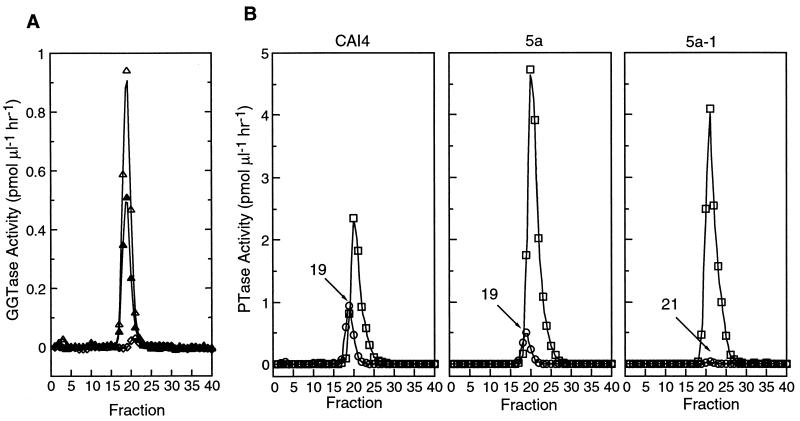

We suspected that the residual activity remaining in the cdc43 mutants when assayed with Ras-CVIL was due to geranylgeranylation by FTase, since we have previously observed a very low level of C. albicans FTase-catalyzed geranylgeranylation of this acceptor (27). To confirm this point, GGTase I and FTase activities were partially resolved by anion-exchange chromatography, and column fractions were assayed for PTase activity with Ras-CVIL and GGPP and with Ras-CVLM and FPP. As shown in Fig. 5A, a gene dosage-dependent loss of GGTase I activity was evident and a small peak of residual geranylgeranylation activity was observed in the cdc43 mutant 5a-1, which is shifted two fractions relative to peak GGTase I activity in the wild type and the CDC43-disrupted heterozygote. The resolution of GGTase I and FTase in each of the three strains is shown in Fig. 5B, from which is appears that the peak of residual GGTase I activity is coincident with the FTase activity.

FIG. 5.

Residual geranylgeranylation activity in Cacdc43 null mutants is due to FTase. GGTase I and FTase activities were partially resolved by chromatography of S100 fractions as described in Materials and Methods. The samples loaded were CAI4, 5.4 mg; 5a, 7.8 mg; and 5a-1, 7.4 mg. Individual column fractions were assayed for GGTase I and FTase activities with Ras-CVIL (20 μM) and GGPP (4 μM) or Ras-CVLM (20 μM) and FPP (4 μM), respectively. (A) GGTase I activity in CAI4 (open triangles), 5a (solid triangles), and 5a-1 (diamonds). (B) Comparison of GGTase I (circles) and FTase (squares) profiles in CAI4, 5a, and 5a-1.

Distribution of GGTase I substrates in Cacdc43 mutants.

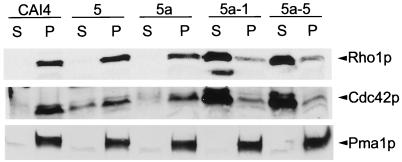

Since prenylation affects protein hydrophobicity, we expected the subcellular localization of GGTase I substrates to change in the cdc43 mutants. It had previously been shown for S. cerevisiae ts cdc43 mutants that soluble levels of either Cdc42p or Rho1p were elevated at the restrictive temperature, depending upon the specific ts allele (33, 54). We fractionated extracts into particulate and soluble fractions and determined the subcellular distribution of Cdc42p and Rho1p by Western blot analysis. Both Rho1p and Cdc42p localized predominantly to the membrane or pellet fraction in wild-type CAI4 and the CDC43-disrupted heterozygotes, 5 and 5a (Fig. 6). In the cdc43 mutants 5a-1 and 5a-5, the distribution of Rho1p and Cdc42p was shifted, with the bulk of these proteins localizing to the cytosolic fraction. We also noted what appeared to be an increase in the total amount of Cdc42p and Rho1p in the cdc43 mutants. The protein migrating slightly faster than Rho1p in strain 5a-1 was found occasionally in the null mutants only and is likely to be a degradation product of Rho1p. The distribution of Rho1p and Cdc42p was also shifted from the membranous fraction to the cytosolic fraction in Cacdc43 null mutants 8a-1 and 8a-2, and levels of these proteins were elevated (data not presented). No changes were observed in the distribution or levels of an integral membrane protein that is not a GGTase I substrate, Pma1p, the plasma membrane H+ ATPase, as shown in Fig. 6.

FIG. 6.

Western blot analysis of subcellular distribution of Rho1p and Cdc42p in Cacdc43 null mutants and parent strains. Extracts were fractionated into P100 (microsomal; P) and S100 (cytosolic; S) fractions as described in Materials and Methods. To assess the relative amount of protein in each fraction, equal volumes of the supernatant and particulate fractions of each strain were loaded on an SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel for detection of Rho1p and Cdc42p and on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel for detection of Pma1p. Equal amounts of microsomal protein (2.5 μg for Pma1p detection and 25 μg otherwise) of each strain were loaded. The gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and analyzed with anti-Cdc42p, anti-Rho1p, and anti-Pma1p antibodies as described in Materials and Methods.

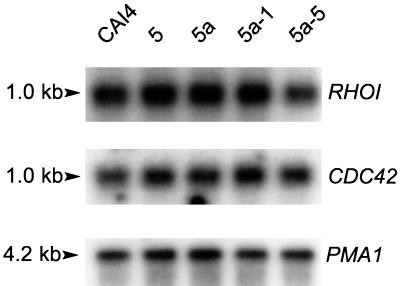

Northern blot analysis was performed on the cdc43 null mutants to assess whether the increased levels of Rho1p and Cdc42p could be attributed to an increase in the levels of their respective transcripts. No differences were found between the RHO1 or CDC42 mRNA levels in the wild type, the CDC43-disrupted heterozygote, and the cdc43 null mutants, as shown in Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Autoradiogram of Northern blot hybridization of C. albicans CDC42 and RHO1 to mRNA from Cacdc43 null mutants and parent strains. A PMA1 probe was used as a control for RNA loading and transfer. The gel blot was hybridized first to the RHO1 and PMA1 probes and was subsequently stripped and rehybridized to the CDC42 probe. The probes were a 670-bp SpeI-XbaI fragment containing CDC42 isolated from pMK2, a 610-bp EcoRI-BglII RHO1 fragment from pTKRBE, and a 2.0-kb EcoRV PMA1 fragment isolated from p37 (29).

GGTase I inhibitors have similar effects on cellular location of substrate proteins.

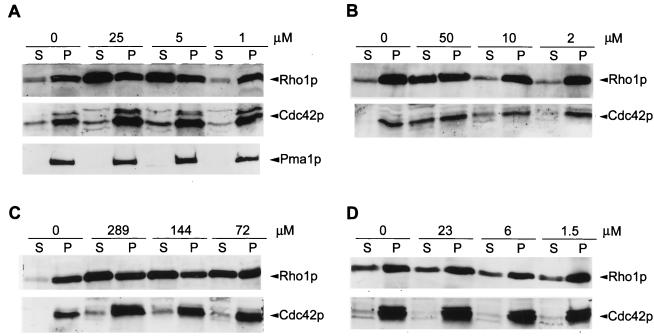

J-109,390 is a potent inhibitor of C. albicans GGTase I with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 120 nM, but it demonstrates no antifungal activity against wild-type C. albicans when tested at concentrations as high as 300 μM (T. Satoh, unpublished data). We treated wild-type MY1055 with J-109,390 and analyzed Rho1p and Cdc42p in the particulate and soluble fractions by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 8A, the distribution of Rho1p changed, with more Rho1p found in the soluble fraction than in the particulate fraction in cells treated with 5.0 and 25 μM J-109,390. It is also evident that the total amount of Rho1p increased. Cdc42p was elevated in both the supernatant and pellet fractions. J-109,390 did not affect the distribution or levels of the control protein, Pma1p. Results obtained with another potent GGTase I inhibitor, L-269,289, which has an IC50 of 100 nM against C. albicans GGTase I (J. Williamson, unpublished data), are shown in Fig. 8B. Treatment with L-269,289 resulted in a moderate increase in Rho1p and a shift in distribution to the soluble fraction at the highest concentration tested. Cdc42p began to appear in the soluble fraction at 10 μM L-269,289. No growth inhibition was obtained with 50 μM L-269,289 under the conditions of this experiment.

FIG. 8.

Western blot analysis of subcellular distribution of Rho1p and Cdc42p in wild-type C. albicans treated with the indicated concentrations of drugs. Extracts were made and the samples were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 6. The results are representative of data from a minimum of two experiments for each condition. (A) J-109,390; (B) L-269,289; (C) L-659,699; (D) anisomycin.

3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl–coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) synthase catalyzes an early step in the formation of mevalonate, which in turn is a precursor in the biosynthesis of GGPP. Inhibition of HMG-CoA synthase should reduce the pool of GGPP and consequently reduce the level of prenylation by GGTase I. The results obtained from treatment with HMG-CoA synthase inhibitor, L-659,699 (C. albicans IC50, 30 nM) (37), are shown in Fig. 8C. Treatment with L-659,699 caused a shift in the distribution of Rho1p and an increase in the protein. We also observed an increase in the total amount of Cdc42p at all concentrations tested and an increase in soluble Cdc42p. No effect on growth was found under the conditions of this experiment.

We also tested several control compounds with different modes of action. Each compound was titrated with a range of concentrations, starting with a level that did not inhibit growth and including at least one concentration that was growth inhibitory. The results obtained with anisomycin, a protein synthesis inhibitor, are shown in Fig. 8D. Anisomycin did not affect the distribution or levels of either Rho1p or Cdc42p at any of the concentrations tested. Similar results were obtained with cerulenin, brefeldin A, and nikkomycin Z (data not presented).

Some variability in the amounts of Rho1p and Cdc42p detectable in the supernatant and pellet fractions was noted from experiment to experiment. However, the patterns we obtained with each drug and each antibody were reproducible. Others have also found that polyclonal antibodies raised against prenylated GTP-binding proteins yield variable results (38).

DISCUSSION

We disrupted the C. albicans homolog of an essential S. cerevisiae gene, CDC43, and found that it is not necessary for viability of the pathogen. C. albicans strains with no GGTase I activity were isolated upon sequential disruption of each of the alleles of CaCDC43. The possibility that the CaCDC43 locus of CAI4 was aneuploid was ruled out at the onset by using a HindIII restriction site polymorphism to distinguish which allele was disrupted. A similar allelic restriction site polymorphism was instrumental in showing that the initial attempts to disrupt the C. albicans URA3 gene were performed in a strain tetraploid at the URA3 locus (19). CaCDC43 is not the first example of a dispensable C. albicans gene with a corresponding essential Saccharomyces homolog. SLN1, encoding a required histidine kinase osmosensor in S. cerevisiae, was recently disrupted in C. albicans, and null mutants are viable (30).

The viability of the Cacdc43 mutants is consistent with our previous in vitro data demonstrating cross-prenylation of GGTase I substrates by C. albicans FTase and the poor anti-Candida activity of potent GGTase I inhibitors known to penetrate the cell. The growth rate of the Cacdc43 mutants is comparable to that of the parent strains until late log phase, and then it differs only marginally. Despite this, the null mutants do show a phenotype. The mutant cells are rounder and larger, clump together, and have substantially fewer buds compared to the parent strain. This phenotype is reminiscent of S. cerevisiae ts cdc43 mutants (2) and C. albicans treated with aculeacin A, which inhibits cell wall biosynthesis (48). Our results suggest that a cell wall defect is tolerated to some extent in C. albicans. We provide evidence to suggest a compensatory mechanism that allows for sustained growth of the Cacdc43 mutants and wild-type C. albicans treated with GGTase I inhibitors.

The absence of GGTase I activity in the Cacdc43 mutants in vitro correlates with the effects on prenylation in vivo, as seen by the pronounced shift in distribution from the particulate to the soluble fraction of two GGTase I substrates, Rho1p and Cdc42p. This phenotype is also observed in S. cerevisiae ts cdc43 mutants grown at the nonpermissive temperature and results from the lack of the hydrophobic prenyl group (33, 54). Earlier experiments had shown that if the cysteine of the CaaX box of S. cerevisiae Cdc42p was mutated to serine, precluding prenylation, Cdc42p was found almost exclusively in the soluble fraction (53). Direct characterization of prenyl group formation in vivo in S. cerevisiae is difficult, since it does not take up exogenous mevalonate or other precursors of the prenyl group well enough for radiolabeling studies to be performed. We have also found that mevalonate is incorporated poorly in C. albicans (data not presented).

Our data suggest that the inhibition or absence of C. albicans GGTase I results in a compensatory mechanism based on the net accumulation of at least two of its substrates, Cdc42p and Rho1p. This endogenous compensation is similar to the correction of the lethal growth defect of an S. cerevisiae cdc43 null mutant by simultaneous artificial overexpression of both CDC42 and RHO1 (35, 46). Levels of Cdc42p and Rho1p were elevated in the Cacdc43 mutants and in wild-type C. albicans treated with potent GGTase I inhibitors. The GGTase I inhibitors J-109,390 and L-269,289 resulted in a significant increase in the Rho1p detected, as did treatment with L-659,699, an HMG-CoA synthase inhibitor which is expected to reduce the cellular pool of GGPP and secondarily to affect GGTase I. Treatment with J-109,390 and L-659,699 also led to an elevation of Cdc42p, detected by Western blot analysis. Accumulation of these GGTase I substrates in C. albicans is likely due to a posttranscriptional mechanism, as we observed no apparent increases in mRNA levels of RHO1 or CDC42 in the Cacdc43 mutants. Although the Western analysis was not quantitative, we estimate that the amount of Rho1p and Cdc42p is more than twofold greater in the Cacdc43 null mutants than in the wild type. We would have been able to detect an increase as small as 1.5- to 2-fold in the levels of the corresponding mRNA transcripts. We have described the changes in levels of Rho1p and Cdc42p in relative terms, as we cannot precisely quantitate Rho1p and Cdc42p by using the data from the Western blots. Immunoprecipitation of Cdc42p and Rho1p should allow exact quantitation of these GGTase I substrates, but it may not be possible with existing antibodies. We have recently learned that more consistent immunoprecipitations are obtained if prenylated GTP-binding proteins are epitope tagged and immunoprecipitated with antiserum raised against the epitope (38).

Saccharomyces cdc43 mutants in which Rho1p and Cdc42p are overexpressed grow slowly, but their growth is improved if the CaaX boxes of the overproduced proteins are altered to that of an FTase substrate (35). In the absence of Saccharomyces GGTase I, FTase becomes essential, and in fact, growth of the strains is enhanced when FTase is elevated, suggesting that FTase prenylates the required GGTase I substrates (46). Similarly, we propose that in response to limiting GGTase I in C. albicans, elevated levels of Rho1p and Cdc42p enable these proteins to compete with FTase substrates for prenylation by FTase, resulting in sustained growth. This hypothesis explains both the viability of the Cacdc43 mutants and the poor antifungal activity of potent, but specific, GGTase I inhibitors that we know are capable of penetrating the cell (J. Onishi, unpublished data; T. Satoh, unpublished data). Our hypothesis is applicable to more than one C. albicans strain, as the compensatory mechanism was observed in strains derived from CAI4 and in MY1055, a clinical isolate that we routinely use in mouse models for pathogenesis.

Consistent with the above hypothesis, the GGTase I inhibitor J-109,390 (C. albicans GGTase I IC50, 120 nM; MIC, >300 μM) is at least 2,500-fold less potent against C. albicans FTase (T. Satoh, unpublished data). Two lines of evidence indicated that the failure of J-109,390 to inhibit growth was not due to an inability to penetrate the cell. Previously it was shown that J-109,390 inhibited β-1,3 glucan synthase activity in vivo and shifted the distribution of Rho1p from the membranes to the cytosol (T. Satoh, unpublished data). We confirmed that J-109,390 caused an increase in soluble Rho1p and additionally caused an elevation of this protein. Interestingly, although we detected an increase in Cdc42p upon treatment with J-109,390, we did not see a shift in the distribution of Cdc42p from the particulate to the soluble fraction. It is possible that some inhibitors, such as J-109,390, may preferentially prevent prenylation of a subset of substrates. Similar substrate discrimination has been reported by Ohya et al., who observed that some ts mutations in CDC43 of S. cerevisiae GGTase I led to an increase in soluble Cdc42p whereas another resulted in an increase in soluble Rho1p (33). The other GGTase I inhibitor tested, L-269,289, affected the distribution of both substrates.

In agreement with our hypothesis that FTase farnesylates rather than geranylgeranylates GGTase I substrates when GGTase I is absent in C. albicans, the in vitro specific activity for farnesylation of either substrate tested, Cdc42p (1.1 pmol/min/mg) or Ras-CVIL (21.4 pmol/min/mg), was 36- to 112-fold higher than the specific activity of geranylgeranylation (0.03 and 0.19 pmol/min/mg, respectively) in crude extracts prepared from the Cacdc43 null mutants 5a-1 and 5a-5 (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Interestingly, in extracts from wild-type CAI4, the specific activity of farnesylation of Ras-CVIL was threefold higher than the specific activity of geranylgeranylation (data not shown). However, the determination of which prenyl group is added in vivo in C. albicans when GGTase I is limiting may depend upon the relative pools of FPP and GGPP in the cell at any given growth state. It is also conceivable that under normal conditions a small percentage of either Rho1p or Cdc42p is prenylated by FTase. Chemical analysis of the prenyl groups formed in vivo will be necessary to address these issues, and it awaits development of the appropriate radiolabeling techniques.

Recent studies with mammalian farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) describe a similar phenomenon; proteins that are normally FTase substrates may become geranylgeranylated when FTase activity is limiting. Treatment of mammalian cells with the FTI SCH 44342, SCH 56582, B956, or B957 led to the geranylgeranylation of N-Ras, K-Ras, or both. These proteins are normally farnesylated in vivo (40, 47). Similarly, FTI L-739,749 resulted in a decrease in farnesylated RhoB concomitant with an increase in geranylgeranylated RhoB (23). RhoB is unusual in that it is normally both farnesylated and geranylgeranylated in vivo.

It is possible that FTase is upregulated in response to limiting GGTase I. In some cases a modest elevation (≤1.5-fold) in Ras-CVLM farnesylation was observed for the Cacdc43 mutants (Fig. 5 and data not shown). However, a similar increase in farnesylation of the alternate substrate Cdc42p (Fig. 4) or Ras-CVIL (data not shown) was not detected, suggesting that wild-type levels of FTase are sufficient in the Cacdc43 mutant. Further studies will be needed to determine if the synthesis or activity of FTase is upregulated in response to limiting GGTase I.

Perhaps some or all of the Rho1p and Cdc42p remaining in the pellet fraction when GGTase I is limiting is not prenylated and becomes membrane associated by mass action. There is evidence in the literature that nonprenylated proteins retain some function. Prenylation of mammalian RhoB is required for cell transformation but not for its ability to activate serum response element-dependent transcription (24). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, overexpression of a constitutively active mutant allele of Rho1p that is prenylated resulted in a fourfold increase in 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase activity which became GTP independent (4). If the CaaX box of the constitutively expressed Rho1p was mutated to preclude prenylation, glucan synthase activity was still enhanced but the increase was just twofold, and only 50% of the activity was GTP dependent.

It seems unlikely that the viability of the C. albicans Cacdc43 null mutants is due to prenylation of GGTase I substrates by GGTase II, since the substrate specificities of GGTase IIs characterized to date differ significantly from that of GGTase I (12, 52). To our knowledge, there are no examples of cross-prenylation of GGTase I substrates by GGTase II. However, we cannot rule out this possibility entirely, since GGTase II from C. albicans has not yet been characterized. Alternatively, C. albicans could possess a second GGTase I not detectable by our current in vitro assay conditions. Southern blot hybridization under high-stringency conditions did not reveal a CaCDC43 homolog (E. Register and R. Kelly, unpublished observations). To prove conclusively that prenylation of GGTase I substrates by FTase is responsible for the viability of the Cacdc43 mutants, it will be necessary to disrupt the β subunit of FTase in the Cacdc43 mutants. If this double mutant is nonviable, as we expect, a dual GGTase I-FTase I inhibitor can be considered for antimycotic therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to John Rosamond for providing the CA124 C. albicans genomic DNA library. We thank Jennifer Nielsen, Maria Meinz, and Doug Johnson for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Tracey Klatt for mass spectroscopic analysis and John Polishook for help with microscopy. We appreciate the critical reading of the manuscript by Cameron Douglas, Michael Justice, Suzanne Mandala, and Jennifer Nielsen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzo G K, Flattery A M, Gill C J, Kong L, Smith J G, Krupa D, Pikounis V B, Kropp H, Bartizal K. Evaluation of water-soluble pneumocandins L-733,560, L-705,589, and L-731,373 in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1077–1081. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams E M, Johnson D I, Longnecker R M, Sloat B F, Pringle J R. CDC42 and CDC43, two additional genes involved in budding and the establishment of cell polarity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:131–142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arellano M, Coll P M, Yang W, Duran A, Tamanoi F, Perez P. Characterization of the geranylgeranyl transferase type I from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1357–1367. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeke J D, LaCroute F, Fink G R. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplin B E, Hettich L A, Marshall M S. Substrate characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein farnesyltransferase and type-I protein geranylgeranyltransferase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1205:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke S. Protein isoprenylation and methylation at carboxyl-terminal cysteine residues, Annu. Rev Biochem. 1992;61:355–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox G M, Perfect J R. Fungal infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1993;6:422–426. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drgonova J, Drgon T, Tanaka K, Kollar R, Chen G-C, Ford R A, Chan C S M, Takai Y, Cabib E. Rho1p, a yeast protein at the interface between cell polarization and morphogenesis. Science. 1996;272:277–279. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elble R. A simple and efficient procedure for transformation of yeasts. Biotechniques. 1992;13:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farnsworth C C, Seabra M C, Ericsson L H, Gelb M H, Glomset J A. Rab geranylgeranyl transferase catalyzes the geranylgeranylation of adjacent cysteines in the small GTPases Rab1A, Rab3A, and Rab5A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11963–11967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finegold A A, Johnson D I, Farnsworth C C, Gelb M H, Judd S R, Glomset J A, Tamanoi F. Geranylgeranylprotein transferase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is specific for Cys-Xaa-Xaa-Leu motif proteins and requires the CDC43 gene product, but not the DPR1 gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4448–4452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Gene. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He B, Chen P, Chen S, Vancura K L, Michaelis S, Powers S. RAM2, an essential gene of yeast, and RAM1 encode the two polypeptide components of the farnesyltransferase that prenylates a-factor and Ras proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11373–11377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman C S, Winston F. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmid for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imamura H, Tanaka K, Hihara T, Umikawa M, Kamei T, Takahashi K, Sasaki T, Takai Y. Bni1p and Bnr1p: downstream targets of the Rho family small G-proteins which interact with profilin and regulate actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1997;16:2745–2755. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamada Y, Qadota H, Python C P, Anraku Y, Ohya Y, Levin D. Activation of yeast protein kinase C by Rho1 GTPase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9193–9196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly R, Miller S M, Kurtz M B, Kirsch D R. Directed mutagenesis in Candida albicans: one-step gene disruption to isolate ura3 mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:199–208. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohl N E, Diehl R E, Schaber M D, Rands E, Soderman D D, He B, Moores S L, Pompliano D L, Ferro-Novick S, Powers S, Thomas K A, Gibbs J B. Structural homology among mammalian and Saccharomyces cerevisiae isoprenyl-protein transferases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18884–18888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohno H, Tanaka K, Mino A, Umikawa M, Imamura H, Fujiwara T, Fujita Y, Hotta K, Qadota H, Watanabe T, Ohya Y, Takai Y. Bni1p implicated in cytoskeletal control is a putative target of Rho1p small GTP binding protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1996;15:6060–6068. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondoh O, Tachibana Y, Ohya Y, Arisawa M, Watanabe T. Cloning of the RHO1 gene from Candida albicans and its regulation of β-1,3-glucan synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7734–7741. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7734-7741.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebowitz P F, Casey P J, Prendergast G C, Thissen J A. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors alter the prenylation and growth-stimulating function of RhoB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15591–15594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lebowitz P F, Du W, Prendergast G C. Prenylation of RhoB is required for its cell transforming function but not its ability to activate serum response element-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16093–16095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer M L, Caplin B E, Marshall M S. CDC43 and RAM2 encode the polypeptide subunits of a yeast type I protein geranylgeranyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20589–20593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazur P, Baginsky W. In vitro activity of 1,3-β-D glucan synthase requires the GTP-binding protein Rho1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14604–14609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazur P, Register E, Bonfiglio C A, Yuan X, Kurtz M B, Williamson J M, Kelly R. Purification of geranylgeranyltransferase I from Candida albicans and cloning of the CaRAM2 and CaCDC43 genes encoding its subunits. Microbiology. 1999;145:1123–1135. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirbod F, Nakashima S, Kitajima Y, Cannon R D, Nozawa Y. Molecular cloning of a Rho family, CDC42Ca gene from Candida albicans and its mRNA expression changes during morphogenesis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1997;35:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monk B C, Kurtz M B, Marrinan J A, Perlin D S. Cloning and characterization of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase from Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6826–6836. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6826-6836.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagahashi S, Mio T, Ono N, Yamada-Okabe T, Arisawa M, Bussey H, Yamada-Okabe H. Isolation of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1, the genes for osmosensing histidine kinase homologues, from the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:425–432. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing for yeasts. Proposed standard. Document M27. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nonaka H, Tanaka K, Hirano H, Fujiwara T, Kohno H, Umikawa M, Mino A, Takai Y. A downstream target of RHO1 small GTP-binding protein is PKC1, a homolog of protein kinase C, which leads to activation of the MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:5931–5938. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohya Y, Caplin B E, Qadota H, Tibbetts M F, Anraku Y, Pringle J R, Marshall M S. Mutational analysis of the β-subunit of yeast geranylgeranyl transferase I. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohya Y, Goebl M, Goodman L E, Peterson-Bjorn S, Firesen J D, Tamanoi F, Anraku Y. Yeast CAL1 is a structural and functional homologue to the DPR1 (RAM) gene involved in ras processing. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12356–12360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohya Y, Qadota H, Anraku Y, Pringle J R, Botstein D. Suppression of yeast geranylgeranyl transferase I defect by alternative prenylation of two target GTPases, Rho1p and Cdc42p. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1017–1025. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.10.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omer C, Gibbs J. Protein prenylation in eukaryotic microorganisms: genetics, biology and biochemistry. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onishi J, Abruzzo G, Fromtling R, Garrity G, Milligan J, Pelak B, Rozdilsky W, Weissberger B. Mode of action of β-lactone 1233A in Candida albicans. Antifungal Drugs. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1988;544:230. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overmeyer J H, Erdman R A, Maltese W A. Membrane targeting via protein prenylation. In: Clagg R, editor. Protein targeting protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qadota H, Python C P, Inoue S B, Arisawa M, Anraku Y, Zheng Y, Watanabe T, Levin D E, Ohya Y. Identification of yeast Rho1p GTPase as a regulatory subunit of 1,3-β-glucan synthase. Science. 1996;272:279–281. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowell C A, Kowalczyk J J, Lewis M D, Garcia A M. Direct demonstration of geranylgeranylation and farnesylation of Ki-Ras in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14093–14097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J E, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd. ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schafer W R, Rine J. Protein prenylation: genes, enzymes, targets, and functions. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;30:209–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherlock G, Gahman A M, Mahal A, Shieh J, Ferreira M, Rosamond J. Molecular cloning and analysis of CDC28 and cyclin homologues from the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:716–723. doi: 10.1007/BF00297278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson J R, Register E, Curotto J, Kurtz M, Kelly R. An improved protocol for the preparation of yeast cells for transformation by electroporation. Yeast. 1998;14:565–571. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980430)14:6<565::AID-YEA251>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trueblood C A, Ohya Y, Rine J. Genetic evidence for in vivo cross-specificity of the CaaX-box protein prenyltransferases farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase-I in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4260–4275. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whyte D B, Kirschmeir P, Hockenberrry T N, Numez-Oliva I, James L, Cation J J, Bishop W R, Pai J. K- and N-ras are geranylgeranylated in cells treated with farnesyl protein transferase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14459–14464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi H, Hiratani T, Iwata K, Yamamoto Y. Studies on the mechanism of antifungal action of aculeacin A. J Antibiot. 1982;35:210–219. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamochi W, Tanaka K, Nonaka H, Maeda A, Musha T, Takai Y. Growth site localization of Rho1 small GTP-binding protein and its involvement in bud formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1077–1093. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yokoyama K, Goodwin G W, Ghomashci F, Glomset J. A protein geranylgeranyltransferase from bovine brain: implications for protein prenylation specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5302–5306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang F L, Casey P J. Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:241–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziman M, O'Brien J M, Ouellette L A, Church W R, Johnson D I. Mutational analysis of CDC42Sc, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene that encodes a putative GTP-binding protein involved in the control of cell polarity. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3537–3544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziman M, Preuss D, Mulholland J, O'Brien J M, Bostein D, Johnson D I. Subcellular localization of Cdc42p, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae GTP-binding protein involved in the control of cell polarity. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1307–1316. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.12.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]