Abstract

Dissolved oxygen (O2) is essential for most ocean ecosystems, fuelling organisms’ respiration and facilitating the cycling of carbon and nutrients. Oxygen measurements have been interpreted to indicate that the ocean’s oxygen-deficient zones (ODZs) are expanding under global warming1,2. However, models provide an unclear picture of future ODZ change in both the near term and the long term3–6. The paleoclimate record can help explore the possible range of ODZ changes in warmer-than-modern periods. Here we use foraminifera-bound nitrogen (N) isotopes to show that water-column denitrification in the eastern tropical North Pacific was greatly reduced during the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO) and the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO). Because denitrification is restricted to oxygen-poor waters, our results indicate that, in these two Cenozoic periods of sustained warmth, ODZs were contracted, not expanded. ODZ contraction may have arisen from a decrease in upwelling-fuelled biological productivity in the tropical Pacific, which would have reduced oxygen demand in the subsurface. Alternatively, invigoration of deep-water ventilation by the Southern Ocean may have weakened the ocean’s ‘biological carbon pump’, which would have increased deep-ocean oxygen. The mechanism at play would have determined whether the ODZ contractions occurred in step with the warming or took centuries or millennia to develop. Thus, although our results from the Cenozoic do not necessarily apply to the near-term future, they might imply that global warming may eventually cause ODZ contraction.

Subject terms: Biogeochemistry, Palaeoceanography, Palaeoclimate

By using foraminifera-bound nitrogen isotopes, it is shown that, during two warm periods of the Cenozoic, oxygen-deficient zones contracted rather than expanded, suggesting that global warming may not necessarily lead to increased oceanic anoxia.

Main

Observations indicate that oxygen concentrations have been decreasing in coastal and open-ocean waters over the past five decades, substantially expanding the volume of the ocean’s ODZs1,2. The global deoxygenation trend has been attributed to the decreased oxygen solubility and enhanced upper-ocean stratification expected from global warming, with predictions that global oxygen concentration will continue to decrease over the next decades and centuries, affecting marine ecosystems7. However, there is controversy as to the future of the ODZs in particular, with predictions of both expansion and contraction3–6.

Earth’s climate has evolved in response to tectonic and orbital forcing over the Cenozoic era, the past 66 million years (Myr). Overall, atmospheric CO2 concentrations have decreased and global climate has cooled8. Against this background of Cenozoic cooling, there were two distinct periods of prolonged warm climate: the MMCO, about 6 °C warmer than today, and the EECO, about 13 °C warmer than today9. The MMCO and the EECO were characterized by higher CO2 (around 550 ppm and 1,650 ppm, respectively) and reduced or no continental ice10–12. These two climate optima present an opportunity to investigate the response of ocean oxygen concentrations to prolonged warmth13.

The ratio of N isotopes in the ocean is sensitive to oxygen deficiency, or ‘suboxia’ (a dissolved O2 concentration of less than approximately 5 µmol kg−1, based on standard measurements). Bacterial reduction of nitrate to N2 (‘denitrification’) requires suboxia and discriminates against 15N. Consequently, denitrification in the ODZs of the ocean water column causes an elevation in the 15N/14N ratio, or δ15N, of nitrate in the regions of the ODZs14, also increasing the nitrate δ15N of the global ocean15 (δ15N = ((15N/14N)sample/(15N/14N)atmN2 − 1)) × 1,000‰). The isotopic signal of ODZ denitrification is incorporated into newly formed biomass in the surface ocean, the by-products of which accumulate in deep-ocean sediments. Thus, the N isotopes provide a tool for reconstructing past changes in ODZ-hosted denitrification16. Organic matter that is native to and trapped within the mineral matrix of planktic foraminifer shells (foraminifer-bound organic matter) has been developed as an archive of the N isotopic history of surface ocean productivity17. Foraminifer-bound organic matter is isolated from the sedimentary environment by the mineral matrix, preserving the original unaltered N isotopic signal even over millions of years18. In areas of complete nitrate consumption, foraminifer-bound δ15N records the δ15N of the nitrate in the underlying pycnocline19. Pycnocline nitrate δ15N bears regional signals of water-column denitrification and of N2 fixation, the dominant source of biologically available (that is, ‘fixed’) N to the ocean20. Pycnocline nitrate δ15N will also vary with the δ15N of mean ocean nitrate. Mean ocean nitrate δ15N, in turn, is largely controlled by the relative proportions of denitrification occurring in the water column versus the sediments15.

N isotope and temperature reconstructions

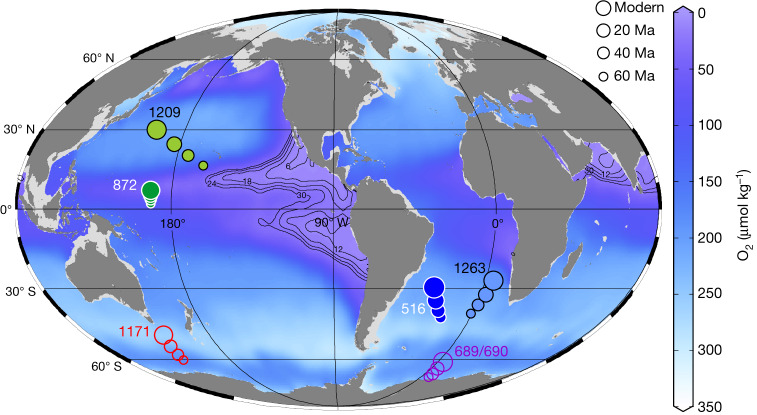

In this study, we measure the δ15N of foraminifer-bound organic matter (FB-δ15N) to investigate changes in the marine N cycle over the Cenozoic. We present new species-specific FB-δ15N data since the Miocene, as well as genus-specific measurements across the early Miocene, Oligocene and late Eocene epochs from two sediment cores, one located in the Pacific (ODP Site 872) and the other in the Atlantic (DSDP Site 516) (Fig. 1). These data are compiled with previously published mixed-taxa and genus-specific FB-δ15N data from the Eocene and Palaeocene epochs at Pacific ODP Site 1209 and Atlantic ODP Site 1263, respectively (Fig. 1), with the merged datasets covering much of the Cenozoic (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Sites from which core data are reported or discussed, plotted over modern dissolved O2 concentrations at 350 m water depth.

Tectonically driven changes in site locations are shown with symbol size (see legend). Filled circles indicate cores with FB-δ15N data, from this study (872/516) and from Kast et al.18 (1209/1263), and open circles indicate cores with foraminiferal δ18O data discussed in the text37,41 (and references therein). Dissolved O2 concentrations (in μmol kg−1) are shown in colour.

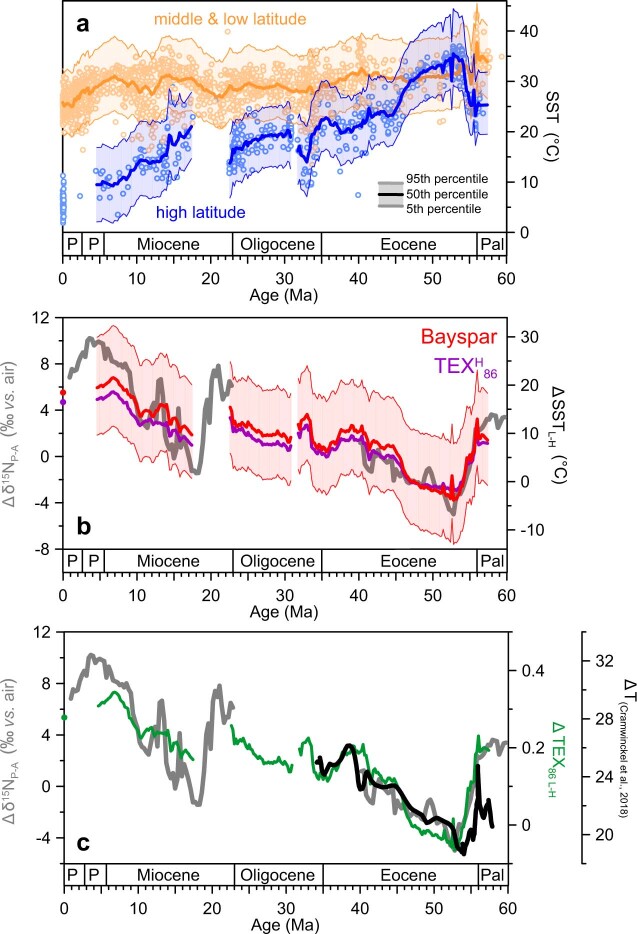

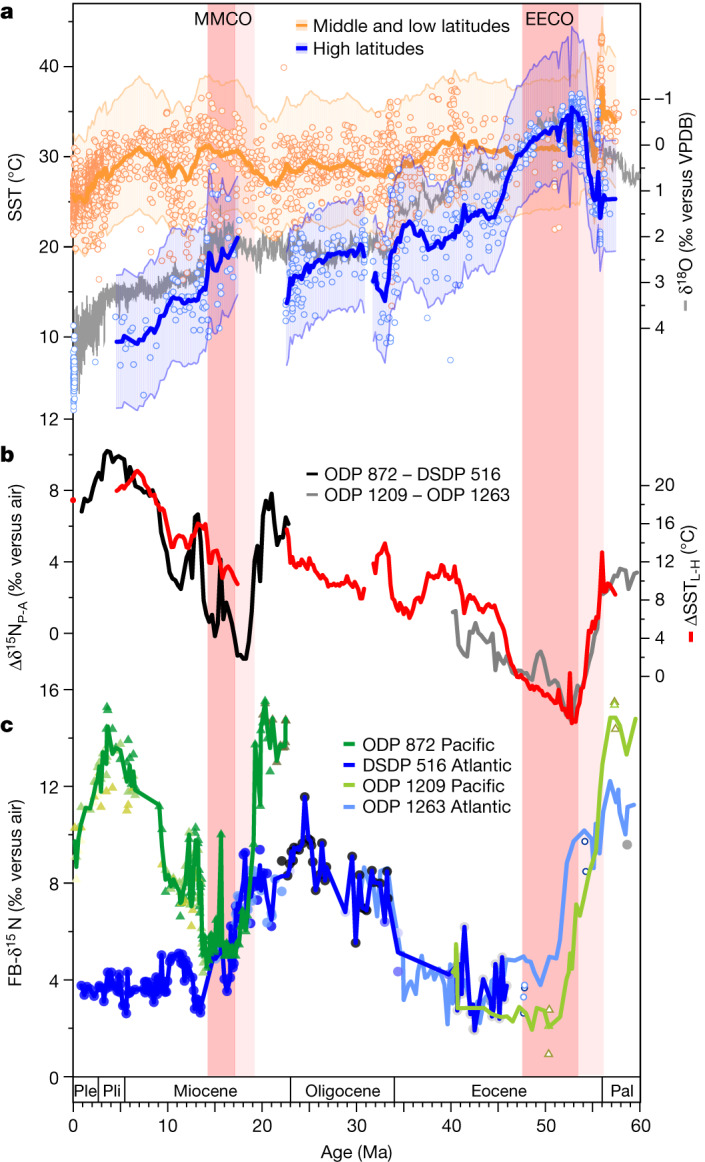

Fig. 2. Evolution of FB-δ15N and climate over the Cenozoic.

a, Compilation of new and previously published SST data based on the TEX86 palaeothermometer, divided into high latitudes (above 50° N/S) and low/middle latitudes (0–40° N/S), with LOESS smoothing (factor 0.02) and 90% confidence interval (see Methods and Supplementary Data 2). TEX86 temperature estimates are based on the BAYSPAR calibration (see Methods). The grey line shows the benthic foraminiferal oxygen isotope ratio (δ18O) compilation by Westerhold et al.8. b, Δδ15NP-A is the FB-δ15N difference between Pacific ODP Site 872 and Atlantic DSDP Site 516 (black line) or between Pacific ODP Site 1209 and Atlantic ODP Site 1263 (grey line). ΔSSTL-H (red line) is the SST difference between low/middle latitudes and high latitudes (from a; the propagated 90% confidence interval for ΔSSTL-H is shown in Extended Data Fig. 4b). c, Average of species-specific FB-δ15N from ODP Site 872 (green) and DSDP Site 516 (blue), together with mixed-taxa FB-δ15N from ODP Site 1209 (light green) and ODP Site 1263 (light blue), calculated as the average of the two size fractions18. Triangles and circles of different colours indicate individual species-specific or genus-specific FB-δ15N in Site 872/1209 and Site 516/1263, respectively (see Extended Data Fig. 1 for details). Light pink bars indicate the first signs of global warming into the EECO and the MMCO, and darker bars indicate the main warm intervals, based on the benthic foraminifer δ18O (a). Ple, Pleistocene; Pli, Pliocene; Pal, Palaeocene.

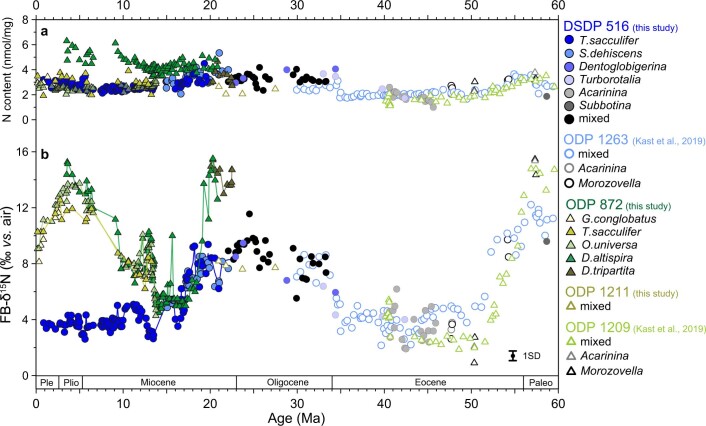

Extended Data Fig. 1. Cenozoic foraminifer-bound nitrogen isotope and nitrogen content data compilation, with sites and taxa indicated.

Foraminifer-bound N content (a) and FB-δ15N (b) for species-specific analyses in DSDP Site 516, ODP Site 872 and ODP Site 1211, complemented by data from mixed taxa and specific genera by Kast et al.18 for ODP Sites 1263 and 1209. Our compilation is of putatively symbiotic taxa or coarse fractions dominated by symbiotic taxa, avoiding the need to correct for the typical offset between symbiotic and symbiont-barren species19,89. Cross-plots between δ15N and N content show no correlation.

In addition, we have generated a TEX86-based21 sea surface temperature (SST) compilation that includes new measurements as well as previously published data (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3). The compilation shows the thermal evolution of the upper ocean at low/middle and high latitudes. The SST compilation allows us to reconstruct the low-to-high-latitude SST gradient (ΔSSTL-H) using a single temperature proxy (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Figs. 2–4). ΔSSTL-H may be a particularly sensitive indicator of past climate change, and it provides constraints on the circulation of the atmosphere and ocean.

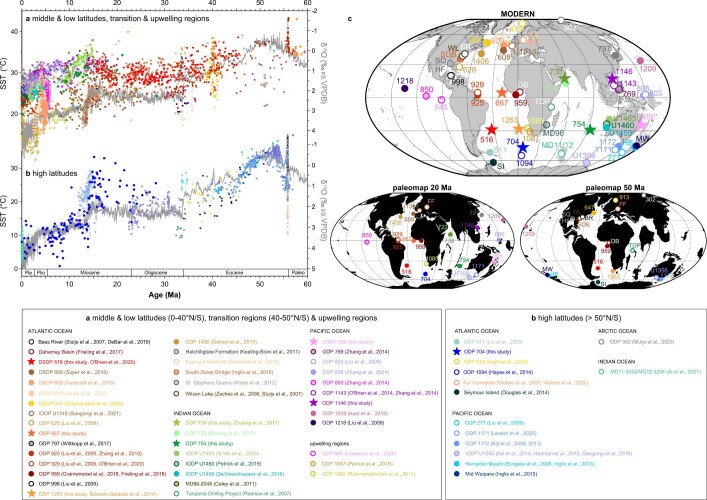

Extended Data Fig. 2. Cenozoic TEX86 Bayspar-derived SST compilation.

SSTs are categorized in middle and low latitudes with transition and upwelling regions (a) and high latitudes (b). Grey line indicates benthic oxygen isotope compilation by Westerhold et al.8. c, Maps with core locations: modern map shows current locations of core sites. Palaeomap at 20 Ma with palaeorecords spanning 10–30 Ma and palaeomap at 50 Ma with palaeorecords spanning 40–60 Ma. Maps are adapted from the Ocean Drilling Stratigraphic Network (ODSN) Paleomap project (http://www.odsn.de/odsn/services/paleomap/paleomap.html, accessed May 2022). Palaeolatitudes for core sites are calculated after van Hinsbergen et al.52.

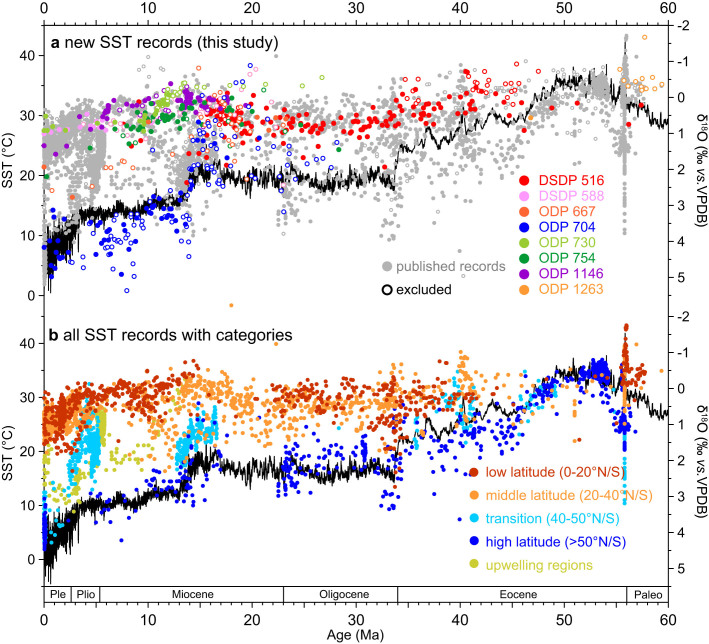

Extended Data Fig. 3. Cenozoic TEX86 Bayspar-derived SST compilation, categorized on the basis of latitude.

a, TEX86 Bayspar -derived SST data generated in this study are in red (DSDP Site 516), pink (DSDP Site 588), dark orange (ODP Site 667), blue (ODP Site 704), light green (ODP Site 730), green (ODP Site 754), purple (ODP Site 1146) and light orange (ODP Site 1263). In grey are published SST records from our compilation (Supplementary Data 2). Open dots of different colours indicate samples that have been excluded due to anomalous GDGTs distributions (see Methods). b, TEX86 Bayspar-derived SST records categorized in low (0–20° N/S, red) and middle (20–40° N/S, orange) latitudes, transition regions (40–50° N/S, light blue), high latitudes (>50° N/S, blue) and upwelling regions (green). Black line indicates benthic oxygen isotope compilation8.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Comparisons and confidence intervals for TEX86-derived SST reconstructions.

a, TEX86 Bayspar-derived SST for middle and low (orange) and high (blue) latitudes datasets with corresponding 90% confidence interval. b, Comparison between δ15N-gradient (Δδ15NP-A) and latitudinal SST-gradient (ΔSSTL-H) calculations, using two SST calibrations: SSTBayspar after Tierney and Tingley138 (with the propagated 90% confidence interval from a) and SSTTEXH after Kim et al.137. c Latitudinal TEX86-gradient (ΔTEX86 L-H) in comparison with the latitudinal SST gradient proposed by Cramwinckel et al.99. (ΔT = SSTTEXH86 − SSTδ18O, black line). Note that ΔTEX86 L-H does not depend on the calibration used.

The new data show that Atlantic and Pacific FB-δ15N values were elevated with respect to the present during the early Miocene but decreased sharply in the two basins from 19 to 16 million years ago (Ma), with a greater decline in the Pacific (of around 11‰) than in the Atlantic (about 6‰) (Fig. 2c). FB-δ15N reached a minimum at both sites during the MMCO. FB-δ15N then increased during the subsequent cooling phase (from 14 Ma to 10 Ma), known as the Middle Miocene Climate Transition, again with a greater change in the Pacific than in the Atlantic. Finally, during the late Miocene (from 10 Ma to 5 Ma), the records decouple: the Pacific record shows a strong FB-δ15N increase followed by a decline at 3 Ma, whereas the Atlantic record first shows a small decrease and then remains stable until the present.

The compiled data indicate convergent behaviour for the MMCO and the EECO. Both climate optima were characterized by lower Pacific FB-δ15N and a decrease in the FB-δ15N difference between the Pacific and the Atlantic (Δδ15NP-A; Fig. 2b,c). Moreover, both climate optima were associated with strong warming of the high-latitude ocean that reduced the meridional SST gradient (Fig. 2a,b). Δδ15NP-A and ΔSSTL-H are correlated not only during the warming phases but also more broadly through the Cenozoic (Fig. 2b).

Reduced suboxia during warm periods

The coupled declines in δ15N and Δδ15NP-A during the EECO and MMCO are best explained by reductions in water-column denitrification, which today occurs mostly in the eastern tropical Pacific ODZs (Fig. 1). A decline in water-column denitrification, lacking a comparable decline in benthic denitrification, would have lowered the δ15N of mean ocean nitrate15 and, thus, the δ15N in both records. At the same time, if suboxia and water-column denitrification have persistently been concentrated in the Pacific, a decline in water-column denitrification would reduce the elevation of tropical Pacific nitrate δ15N relative to the rest of the ocean, lowering Δδ15NP-A as observed. Thus, contrary to widely held expectations22, our FB-δ15N data indicate a reduction, not an enhancement, of the ODZs during the warmest intervals of the Cenozoic.

Both FB-δ15N and Δδ15NP-A decline sharply at the onset of the EECO. The effect of the Asian–Indian collision on outflow from the Tethys Sea has been proposed as important to this change, through its effect on the temperature of the ocean’s pycnocline18. A similar mechanism might be offered for the reconstructed denitrification decline at the onset of the MMCO, when the proto-Mediterranean underwent greater isolation from the Indian Ocean23. However, this Tethys-outflow-focused interpretation does not explain the subsequent increases in Pacific water-column denitrification indicated by the increase in Δδ15NP-A after each of these warm periods (Fig. 2b).

Other notable tectonic changes roughly overlap with the end of the MMCO. These include the widening of the Drake Passage at 15 Ma after a 10-Myr period of narrowing24 and constrictions of the Indonesian Seaway starting at 25–17 Ma (ref. 25) and of the Central American Seaway (CAS) starting around 9.2 Ma (ref. 26). In a model experiment, CAS closure has been observed to increase regenerated CO2 storage in the Pacific interior27, presumably enhancing suboxia in the eastern Pacific. This and other effects of the CAS closure may help to explain the increases in Pacific FB-δ15N and Δδ15NP-A as well as the relative stability of South Atlantic FB-δ15N after 9.2 Ma (Fig. 2b,c). However, there is no evidence for constriction of the CAS until after the MMCO had ended26. Moreover, even if CAS closure began earlier, it would not explain the decline in Pacific FB-δ15N and Δδ15NP-A into the MMCO. Finally, CAS closure would not have been relevant for the EECO-associated changes.

It is possible that several seaway and/or basin geometry changes conspired to yield the observed MMCO and EECO minima in δ15NP, δ15NA and Δδ15NP-A. However, the δ15N changes that define the minimum at the MMCO are abrupt relative to tectonic changes, and they coincide with the ΔSSTL-H changes (Fig. 3). Moreover, within the MMCO, there is an abrupt δ15N increase at Site 872, coinciding with the Mi-2 glaciation at 15.9 Ma (Fig. 3c), a cooling event without any known connection to tectonics28. These observations argue that the denitrification declines of the MMCO and the EECO are dominantly a common response to the warm conditions of these otherwise distinct periods.

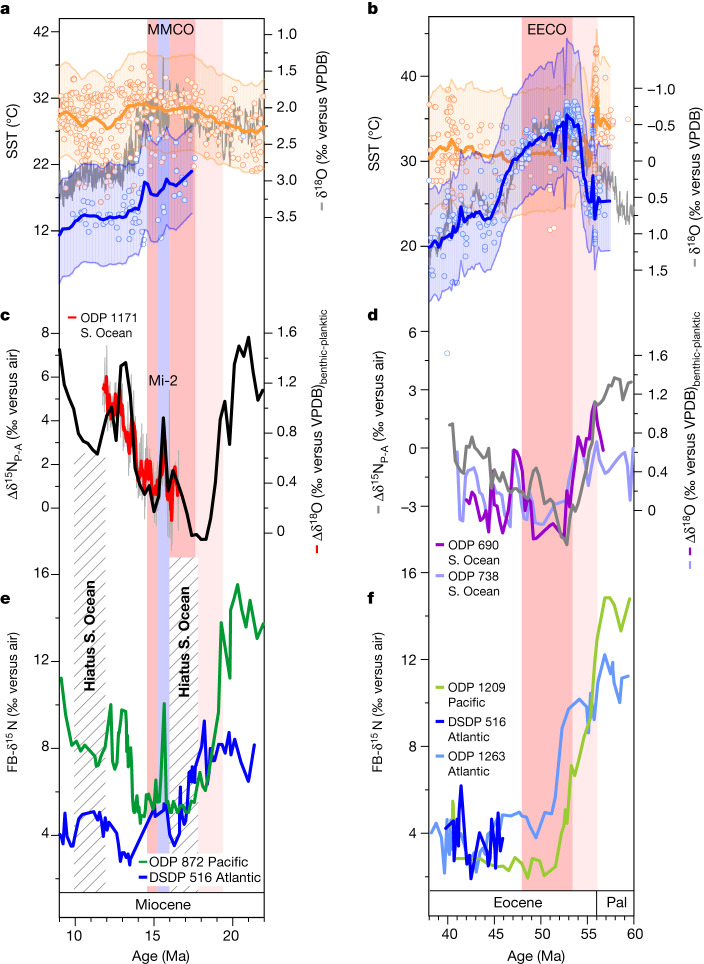

Fig. 3. Focus on the two main Cenozoic warm periods, with additional data pertaining to the Southern Ocean.

The MMCO is on the left and the EECO is on the right. a,b, SST compilation along with the benthic δ18O compilation8, as in Fig. 2. These data indicate, during the climate optima, reductions in the temperature difference between low-latitude and high-latitude surface waters. c,d, FB-δ15N difference between Pacific and Atlantic core sites (Δδ15NP-A), as in Fig. 2. In c and d, other lines indicate running averages of the δ18O difference between benthic and surface-dwelling planktic foraminifers (Δδ18O) in the Southern Ocean (c, ODP Site 1171, red line37,38; d, ODP Sites 690 and 738, purple lines (ref. 41 and references therein)). These data suggest a weaker vertical density gradient in the Southern Ocean during the climate optima, consistent with stronger ventilation of the deep ocean from the Southern Ocean surface. e,f, FB-δ15N records for these time intervals. In e, the lines indicate the average records of species-specific FB-δ15N from ODP Site 872 (green) and DSDP Site 516 (blue). Hatched bars indicate sedimentation hiatuses in the Southern Ocean, which have been attributed to stronger deep-water circulation39. In f, the lines indicate the average records of mixed-taxa FB-δ15N in Site 1209 (light green) and Site 1263 (light blue)18, as in Fig. 2. New species-specific FB-δ15N data from Site 516 are in dark blue. Pal, Palaeocene; S. Ocean, Southern Ocean.

Global ocean nitrate δ15N is strongly modulated by the ratio of sedimentary to water-column denitrification, with a higher ratio yielding a lower δ15N (ref. 15). With warming, the loss of land ice and other processes might cause a sea level rise12, encouraging sedimentary denitrification29. Such a change might be argued to contribute to the low δ15N of the MMCO and the EECO. However, a sea-level-driven change in sedimentary denitrification would produce similar δ15N declines in the Atlantic and Pacific basins. Therefore, the larger decline from extremely high δ15N at Sites 872 and 1209 cannot be explained solely by enhanced sedimentary denitrification; rather, a reduction in water-column denitrification is required18.

Climate-driven ODZ contraction

Climate models point to several processes that work to shrink the ODZs under global warming, offering potential explanations for our finding of reduced water-column denitrification during the MMCO and EECO. First, a decrease in upwelling-supported biological export production in the equatorial and tropical Pacific would reduce oxygen demand in the subsurface4,5,30. Second, circulation changes in the ocean interior, such as enhanced Southern Ocean deep-water formation, may increase oxygen supply3,6. Our TEX86-based reconstructions of SST and ΔSSTL-H are consistent with either mechanism (Fig. 2a,b). On the one hand, the higher global temperatures and weaker ΔSSTL-H during the MMCO and the EECO should have weakened the tropical atmospheric circulation31, which would have decreased eastern equatorial Pacific upwelling4. On the other hand, enhanced deep-water formation in high-latitude regions such as the Southern Ocean may have transported more heat from low to high latitudes, further weakening ΔSSTL-H (ref. 32).

During the MMCO, a reconstruction of equatorial Pacific hydrography indicates a deepening and flattening of the equatorial Pacific thermocline33, which should have caused a reduction in the supply of nutrients to the surface. These findings are consistent with reduced low-latitude export production and, thus, reduced oxygen demand as the cause of ODZ contraction (Fig. 2b). Moreover, a model study5 suggests that global warming decreases the nutrient content of the pycnocline waters ventilating the tropics, reducing tropical export production and causing the ODZs to contract. However, evidence for changes in tropical export production across the MMCO and the EECO is scarce and ambiguous34. Thus, although a tropical-productivity-related explanation is plausible, it remains unconfirmed.

Open-ocean ODZs occur within the pycnocline, which spans approximately 150–1,200 m depth. Accordingly, the ODZs are undoubtedly sensitive to the biogeochemical conditions and circulation at these ‘intermediate’ depths4,5. However, ODZs are also affected by the underlying deep ocean, which contribute water to them through vertical mixing and upwelling, especially near the equator and on the eastern sides of the ocean basins30. In the global-warming simulations that predict ocean reoxygenation on centennial and longer timescales, this reoxygenation results from more vigorous ventilation of the deep ocean, driven by enhanced deep convection in the Southern Ocean3,6.

The oxygen concentration of the deep ocean (and of the ocean interior as a whole) is tightly linked to the ocean’s ‘biological carbon pump’, the storage of respiratory CO2 in deep waters caused by the sinking and subsequent remineralization of organic matter produced in surface waters. A stronger biological pump is associated with more ocean CO2 storage, lower atmospheric CO2, and lower oxygen concentrations in the deep ocean35. The upper limit of the ocean’s biological pump is set by the global mean nutrient (phosphate or nitrate) concentration of the ocean. However, the modern biological pump is weaker than this limit, largely because of ventilation of the deep ocean by the Southern Ocean36, which tends to fill the ocean interior with unused nutrients, reducing oxygen consumption in the ocean interior due to the ‘missed opportunity’ for nutrient-fuelled biological productivity at the Southern Ocean surface. Therefore, the decline in water-column denitrification during the MMCO and the EECO may have been driven by stronger Southern Ocean ventilation of the deep ocean.

This possibility is consistent with other observations. During the MMCO, high-resolution Southern Ocean foraminifer oxygen isotope data from ODP Site 1171 (refs. 37,38) (with a palaeolatitude of about 55° S) show a lower planktic–benthic difference during the MMCO and an increase after the event, coinciding with the increase in Δδ15NP-A (Fig. 3c). These data suggest a reduction in the density gradient between the deep ocean and the Southern Ocean surface, consistent with an increase in deep overturning and a simultaneous weakening of the global biological pump. The records also suggest an episode of stronger Southern Ocean density stratification (high Δδ18Obenthic-planktic), coinciding with the increase in water-column denitrification (high Δδ15NP-A) during the Mi-2 glaciation at about 15.9 Ma (Fig. 3c). Finally, during the MMCO as well as a pause in the following cooling, the most poleward Southern Ocean sediment cores (ODP Sites 689 and 690) contain hiatuses in sedimentation. These hiatuses have been linked to erosional events triggered by the strengthening of deep-water circulation39, further supporting acceleration of deep-ocean ventilation as a cause of the decline in Pacific suboxia (Fig. 3c,e).

During the EECO as in the MMCO, oxygen isotope gradients between planktic and benthic foraminifers decrease substantially in the high-latitude Southern Ocean40 (Fig. 3d), again consistent with an increase in deep overturning that coincided with ODZ contraction. In addition, a global ocean reconstruction of the vertical carbon isotope gradient indicates a weaker global biological pump during the EECO41. These observations support the possibility that enhanced Southern Ocean overturning contributed to the ODZ contractions of both the MMCO and the EECO. Although our focus has been on Southern Ocean overturning, the North Pacific also shows signs of deep-water formation during warm periods of the Cenozoic42,43, a strengthening in which may have had similar effects on the biological pump and ocean oxygen.

A decrease in the efficiency of the ocean’s biological carbon pump would have worked to increase atmospheric CO2 during the MMCO and the EECO. This feedback, albeit with presumed buffering by the ‘weathering thermostat’ on the million-year timescale44, may have amplified these warm climate events. Palaeobiogeochemical data suggest that the modern Southern Ocean’s ventilation of the deep ocean was reduced during the late Pleistocene ice ages45, providing an explanation for the lower oxygen concentration of the ice age deep ocean compared with interglacials and the warm Pliocene43,46–48. This interpretation of the Pleistocene glacial cycles implies a climate sensitivity for Southern Ocean ventilation of the deep ocean that is consistent with our observations from the EECO and the MMCO, which suggest that warming tends to induce an increase in ocean-interior oxygen concentrations.

Implications for future climate

Our measurements indicate that, in past periods of prolonged warmth, ocean suboxia was reduced, not expanded. The possible mechanisms for this change include both short-term and long-term processes3–6, leaving uncertainty as to whether our findings have implications for the coming decades of global warming or only for the longer term. For example, if a decline in tropical Pacific productivity is the main driver of ODZ contraction in a warmer world, then a contraction of the suboxic zones may arise within the coming decades. By contrast, if deep-ocean ventilation is the dominant cause, then our findings would only become important over hundreds of years at the earliest. Regardless, our results indicate that the reported continuing trend towards enhanced open-ocean suboxia1,2 may be the result of multidecadal variability49 or a transient response to the rapid rate of global warming, and not necessarily a permanent response to a warmer climate.

Methods

Core site location

The new FB-δ15N analyses were carried out on two sediment cores from the poleward and equatorward margins of the oligotrophic subtropical gyres in the Atlantic (DSDP Site 516) and the Pacific (ODP Site 872), respectively. DSDP Site 516 (Holes Z and F) (30° 17′ S, 35° 17′ W) was drilled at 1,313 m water depth by the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) during Leg 72 in the southwest Atlantic50. The site is located on the Rio Grande Rise. ODP Site 872 (10° 05′ N, 162° 51′ E, 1095 m water depth) was cored from a sea mount around the Marshall Islands in the eastern equatorial Pacific during Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg 144 (ref. 51). The unconsolidated sediment consists of abundant, well-preserved planktic foraminifers. Our new data are compiled with previously published FB-δ15N data from Pacific ODP Site 1209 and Atlantic ODP Site 1263, most of which are mixed taxa18. In addition, mixed-taxa FB-δ15N measurements were made in several samples of late Oligocene and early Miocene age from Pacific ODP Site 1211 (32° 0′ N, 157° 51′ E, 2,907 m water depth), which is in close proximity to Site 1209 (Extended Data Fig. 1). Past locations were calculated on the basis of ref. 52, or—if available—estimates in ODP reports53,54, and are shown in Fig. 1 (map generated using Ocean Data View software55 and data from ref. 55).

The surface waters above all core sites are environments of complete nitrate consumption and, therefore, should record the δ15N of the nitrate supplied from the pycnocline to the surface. Sites 872 and 1209 are located close to the margin of nitrate-bearing surface waters associated with the equatorial Pacific upwelling. This may modify FB-δ15N relative to the δ15N of the subsurface nitrate supply in the region, most probably increasing FB-δ15N (ref. 56). As a consequence, any reduction in equatorial upwelling at times in the past might have modestly decreased FB-δ15N at Site 872.

We also report new glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) measurements from DSDP Sites 516 and 588 (26° 07′ S, 161° 14′ E, 1,548 m water depth) as well as ODP Sites 667 (4° 34′ N, 21° 55′ W, 3,536 m water depth), 704 (46° 52′ S, 7° 25′ E, 2,543 m water depth), 730 (17° 44′ N, 57° 42′ E, 1,071 m water depth), 754 (30° 56′ S, 93° 34′ E, 1,247 m water depth), 1146 (19° 27′ N, 116° 16′ E, 2,091 m water depth) and 1263 (28° 32′ S, 2° 46′ E, 2,717 m water depth). The new measurements allow us to generate a continuous record of the SST evolution of low-to-middle and high latitudes across the Cenozoic based exclusively on the TEX86 palaeothermometer21.

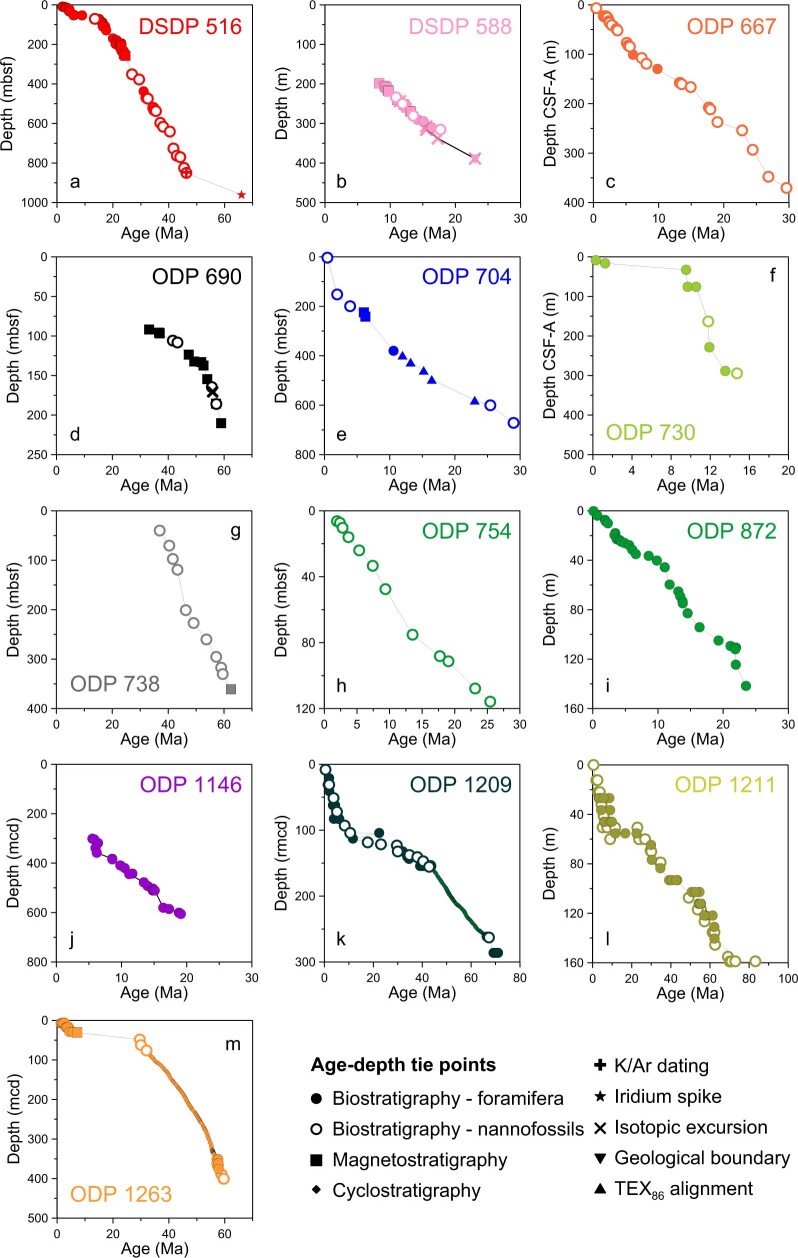

Age models

For DSDP Site 516, we used a combined age model based on biostratigraphic datums57–59 adapted to GTS12 (ref. 60), magnetostratigraphy by Florindo et al.61 and age tie points based on K–Ar dating62 and an iridium spike for the K–Pg boundary63. For ODP Site 872, we used the age model based on biostratigraphic datums64,65 adapted to the GTS12 timescale60. The age models for ODP Sites 1209 and 1263 based on biostratigraphy are described in Kast et al.18. We revised these age models to the astronomically tuned chronologies recently published by Westerhold et al.8,66. The age model for ODP Site 1211 is based on biostratigraphy67. The age model for DSDP Site 588 is based on compiled biostratigraphy, magnetostratigraphy and isotope stratigraphy (Pagani et al.68 and references therein). Ages for ODP Site 667 were determined by linear interpolation of absolute constraints from biostratigraphic (calcareous nannofossils and foraminifers) datums69. Ages for ODP Site 704 were calculated by interpolating biostratigraphic (calcareous nannofossil and foraminifer) datums and magnetostratigraphic data70, and by aligning the new TEX86 record to the TEX86 records from Sites 1171 and U1318 across the middle Miocene climate transition, which are based on high-resolution benthic δ18O stratigraphy71,72. Ages for ODP Site 730 were determined by linear interpolation of biostratigraphic (calcareous nannofossil and foraminifer) datums73. The age model for ODP Site 754 is based on biostratigraphy (calcareous nannofossils)74. The age model for ODP Site 1146 is based on biostratigraphy (foraminifers) reported by Nathan and Leckie75. Ages for ODP Sites 690/689 are based on refs. 41,76. Ages for ODP Site 1171 are based on ref. 71. All the biostratigraphic datums and palaeomagnetic reversals were calibrated to GTS12 (ref. 60) (Supplementary Data 3 and Extended Data Fig. 5).

Extended Data Fig. 5. GTS12-adjusted age models with age tie points.

a, DSDP Site 516 (refs. 57–59,61–63). b, DSDP Site 588 (ref. 68). c, ODP Site 667 (ref. 69). d, ODP Site 690 (ref. 41). e, ODP Site 704 (ref. 70). f, ODP Site 730 (ref. 73). g, ODP Site 738 (ref. 41). h, ODP Site 754 (ref. 74). i, ODP Site 872 (ref. 65). j, ODP Site 1146 (ref. 75). k, ODP Site 1209 (refs. 18,66). l, ODP Site 1211 (ref. 67). m, ODP Site 1263 (refs. 8,18).

Nitrogen isotope analysis

Around 600–800 individual foraminifers from the species Globigerinoides conglobatus, Trilobatus sacculifer, Orbulina universa and Sphaeroidinella dehiscens were picked (250–400-μm size fraction) from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene sections of DSDP Site 516 and ODP Site 872 (Extended Data Fig. 1). Dentoglobigerina altispira and D. tripartita were picked from the >400-μm size fraction. In the Oligocene and Eocene sections of Site 516, we measured genus-specific N isotopes on the genera Dentoglobigerina, Turborotalia, Acarinina and Subbotina, as well as mixed foraminifers. The FB-δ15N measurements were performed in the Martínez-García lab at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry (MPIC). We used the persulfate oxidation-denitrifier method for FB-δ15N first described for planktic foraminifers by Ren et al.17, with minor adjustments in the protocol. As a first step, 5–7 mg of foraminifer tests were gently crushed, transferred to a disposable, 15-ml polypropylene, conical-base centrifuge tube and chemically treated to remove external N contamination. 10 ml of Na-polyphosphate solution (pH 8) was added to the sample tubes, which were ultrasonicated for 10 s to remove clays. After rinsing the sample three times with Milli-Q water (by filling and decanting), 7 ml of a dithionite–citric acid solution (100 ml Milli-Q, 6.2 g sodium citrate, 2 g sodium bicarbonate, 5 g sodium dithionite, 400 μl 4N NaOH) was added to each sample77. Sample tubes were then placed in a water bath at 80 °C for 30 min. After cooling, all samples were rinsed three times with Milli-Q water. Next, an oxidative cleaning step was performed to remove external organic matter: a potassium persulfate/sodium hydroxide solution (2 g recrystallized potassium persulfate, 2 g NaOH pellets, 100 ml Milli-Q water) was added and autoclaved at 125 °C for 65 min. After cooling, the samples were rinsed four times with Milli-Q water and dried overnight in an oven at 60 °C. Next, 3–5 mg cleaned shell fragments were weighed and dissolved in 45 μl 4N hydrochloric acid to release organic matter for analysis. After the CaCO3 dissolution step, organic N was oxidized to nitrate by adding 1 ml of a second recipe of basic potassium persulfate solution (0.7 g recrystallized potassium persulfate, 4 ml 6.25N NaOH solution, 96 ml Milli-Q water). Nitrate concentration was measured for each sample by conversion to nitric oxide followed by chemiluminescence detection78. Subsequently, 5 nmol N of nitrate in the sample solution was converted to nitrous oxide using the denitrifier method, and its δ15N was measured by gas chromatography–isotope ratio mass spectrometry79–82. In contrast to previous studies19,29,83,84, samples were not pH adjusted before injection into the denitrifying bacteria; rather, they were injected without adjustment into 2.75 ml media buffered at pH 6.3 and containing the denitrifying bacteria (see ref. 82,85 for details). To quantify the precision and accuracy of the corrected isotope values, for each series of 30 samples, a total of nine different in-house (MPIC) foraminifer and coral laboratory standards were analysed. The following were analysed (each in triplicate): a coral standard from the taxon Porites (PO-1) with δ15N of 6.2 ± 0.3‰, a coral standard from the taxon Lophelia with δ15N of 10.1 ± 0.4‰ (ref. 85) and a mixed foraminifer standard (63–315-μm size fraction) from the North Atlantic (MSM58-17-1) with δ15N of 5.84‰ (uncertainty not yet assessed). After calibration with international nitrate isotopic references IAEA-NO3 and USGS-34 and correction for the oxidation blank, the long-term analytical precision for the foraminifer standard was 0.23‰ (1 standard deviation, n = 22). The oxidation blank per oxidized sample was typically below 0.2 nmol N.

Analysis of GDGTs

5–20 g of freeze-dried sediment per sample was extracted and separated into two fractions at the Martínez-García lab at the MPIC, following the protocol proposed by Auderset et al.86. After accelerated solvent extraction of the freeze-dried sediment samples, we added 60 μl of an internal standard (C46-GDGT, synthesized by Patwardhan and Thompson87) for quantification. The extracts were dried in a centrifugal Rocket Evaporator (Genevac) and filtered with a polytetrafluoroethylene filter (0.2-μm pore size) with a 1.4% mixture of hexane:isopropanol (hex:IPA). GDGTs were analysed using a high-performance liquid chromatographer (Agilent, 1260 Infinity) coupled to a single-quadrupole mass spectrometer detector (Agilent, 6130) following the protocol proposed by Hopmans et al.88, with some small modifications. Normal-phase separation was achieved with one ultra-high-performance liquid chromatographer silica column (BEH HILIC column, 2.1 mm × 150 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters) maintained at 30 °C. The flow rate of the 1.4% hex:IPA mobile phase was 0.2 ml min−1 and kept constant for the first 25 min, followed by a gradient to 3.5% hex:IPA in 25 min and a column-cleaning step with 10% IPA in hexane. We used a single-ion monitoring of the masses m/z = 1,302.3, 1,300.3, 1,298.3, 1,296.3, 1,292.3, 744.0, 1,050.0, 1,036.0, 1,022.0, 1,020.0 and 1,018.0. The injection volume was 5 μl or 20 μl, depending on the concentration of the samples analysed.

Pacific and Atlantic FB-δ15N stacks

Owing to the emergence and extinction of planktic foraminifer taxa over time, it is important to evaluate the relationship of FB-δ15N of extinct foraminifers to that of modern taxa for which the incorporation of the N isotope signal has been studied19,89,90. Our new dataset from DSDP Site 516 demonstrates that the FB-δ15N of T. sacculifer, a modern photosymbiotic, surface-dwelling species, overlaps with the FB-δ15N of the extinct species S. dehiscens, as well as with the FB-δ15N of mixed planktic foraminifers during the early Miocene and late Oligocene (Extended Data Fig. 1). In addition, during the Oligocene and Eocene epochs, the FB-δ15N from the genera Dentoglobigerina, Turborotalia and Acarinina overlap well with those of S. dehiscens and with mixed species, indicating that there are no notable δ15N offsets between modern and extinct species of foraminifera. At ODP Site 872, O. universa and T. sacculifer, two modern photosymbiotic surface dwellers, show very similar values over the past 15 Myr. In addition, our data show that the FB-δ15N of these two modern species overlap with that of co-occurring D. altispira through the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, despite substantial (but consistent) differences in their N content. Dentoglobigerina altispira δ15N values, in turn, are similar to those of D. tripartita in the early Miocene. In this way, we can combine measurements from different foraminifer species/genera to obtain a continuous record of FB-δ15N throughout the Cenozoic (Extended Data Fig. 1). The FB-δ15N Atlantic and Pacific stacks presented in Fig. 2c are averages of the species-specific, genus-specific and mixed-taxa values shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. As discussed below, ODP Site 1209 migrated north-westward into the North Pacific subtropical gyre after 40 Myr (Fig. 1), so the ODP Site 1209 record is truncated at this age.

Core site migration and FB-δ15N

Seafloor migration is a ubiquitous concern in Cenozoic-long palaeoceanographic reconstructions. Site 1209 warrants consideration in this regard, as it migrated from the ODZ-influenced central tropical North Pacific into the western North Pacific subtropical gyre between the early and mid-Cenozoic (Fig. 1). Several observations indicate that the sharp decline in FB-δ15N at the EECO is not due to site migration. First, the FB-δ15N decline into the EECO also occurs in both the North and the South Atlantic, where site migration would not have had such an effect18 (Fig. 1). Second, the FB-δ15N declines are of similar magnitude for the EECO and the MMCO, arguing that the same dynamic is at work for both warm events. Third, FB-δ15N at Site 1209 shows changes that are opposite to the sense expected from site migration: an approximately 6‰ δ15N increase from the late Cretaceous to the Palaeocene and an approximately 3‰ increase at around 40 Ma (ref. 18). However, the sensitivity of Site 1209 to the isotopic signal of denitrification in the eastern tropical Pacific was eventually reduced by its migration, with the change occurring between the middle Eocene and the early Miocene. This is indicated by the similarity of early Miocene FB-δ15N at Site 1211 (a close neighbour of Site 1209) to the FB-δ15N at South Atlantic Site 516, both of which are substantially lower than FB-δ15N at Pacific Site 872 during the early Miocene (Extended Data Fig. 1). This motivates our use of Site 872 from the Oligocene forward.

Latitudinal SST stacks

For the presented latitudinal SST stack, we combined a total of 653 new TEX86-SST measurements for low (ODP Sites 667 and 730) middle (DSDP Sites 516 and 588, ODP Sites 754, 1146 and 1263) and high latitudes (ODP Site 704) and integrated the records with existing TEX86-SST datasets (which include 4,474 data points out of 53 sites and 48 publications) covering the past 69 Ma (refs. 18,72,91–136). The data and references are summarized in Supplementary Data 2 and shown in Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3. We categorized the different datasets based on age-adjusted palaeolatitudes using paleolatitude.org52. The categories as follows: high latitudes (above 50° N/S), low latitudes (0–20° N/S), mid latitudes (20–40° N/S), transition (40–50° N/S) and costal upwelling regions (Extended Data Fig. 3). Unfortunately, low-latitude sites are scarce and do not provide a continuous SST record across the Cenozoic. Middle-latitude records are more abundant and show SST trends and absolute values that are very similar to those from low latitudes in the intervals in which both records overlap. Consequently, we combined the middle/low latitudes SST records to calculate the latitudinal SST gradient. In Fig. 2, we estimate the gradient between high and middle/low latitudes (ΔSSTL-H = SSTmid/low − SSThigh) after applying a local regression (LOESS) with a smoothing factor of 0.02 and a 0.2-Myr sampling step (using Python code available on GitHub: https://github.com/audersea/Auderset_etal_2022_nature). Sediment cores located in transition regions (with palaeolatitude between 40° and 50° N/S), as well as upwelling-sensitive locations (ODP 1085, ODP 1087 and ODP 846), were not considered in these calculations to minimize the effect of local changes in upwelling intensity and frontal migrations.

To estimate SST from TEX86 values, we used the calibrations proposed by Kim et al.137 (TEXH86) and Tierney and Tingley138 (TEX86 Bayspar, with the following parameters: prior_mean = 28; prior_std = 10; tol = 0.15; n_samp = 2,500). Overall, the trends obtained when calculating the latitudinal temperature gradient are the same for both calibrations, but there are slightly larger amplitudes of change in the Bayspar-derived gradient (Extended Data Fig. 4b). In addition, we have also estimated the latitudinal gradient using the raw TEX86 values for our compilation and compared it to our δ15N gradient (Extended Data Fig. 4c). The good correlation between the raw TEX86 gradient and the δ15N gradient indicate that this is a robust feature that is independent of the calibration used. Finally, we compare our reconstructed latitudinal SST gradient with the one proposed by Cramwinckel et al.99 for the time interval between 58 and 30 Ma, based on the combination of benthic oxygen isotopes records for high latitudes and TEX86 reconstructions for low latitudes (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Both reconstructions agree well; however, the approach followed by Cramwinckel et al.99 is only suitable for periods in which there were no substantial contributions of continental ice to the benthic δ18O signal, limiting its application after the Eocene–Oligocene boundary.

Several indices have been proposed to evaluate potential changes in the source of isoprenoid GDGTs over time110,139–141. We report the values for these indices in Supplementary Data 2. As suggested by previous studies, we exclude GDGTs data with a high methane index (above 0.4) and high GDGTRS (above 30) from our calculation of the latitudinal temperature gradient (355 samples) (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The branched and isoprenoid tetraether (BIT) index has been proposed to estimate the relative contribution of soil-derived GDGTs to aquatic sedimentary environments characterized by large inputs from nearby soils (that is, costal marine sediments and lake sediments)142. In these environments, BIT values below 0.4 have been suggested to indicate minor inputs of terrestrial GDGTs and, therefore, a negligible influence of terrestrial GDGTs on the estimated upper-ocean temperature139. Samples with BIT values above 0.4 are typically not used for palaeotemperature calculation owing to the potential bias that soil GDGTs inputs may introduce on the estimated SST. However, the applicability of this index to estimate terrestrial inputs of GDGTs in open-ocean settings has been questioned because (1) branched GDGTs can be produced in situ143–147 and (2) degradation rates of crenarchaeol are two times higher than those of branched GDGTs148. Thus, in some environments, the BIT index can be high (above 0.4), despite the relatively low terrestrial inputs of brGDGTs. In these cases, samples with BIT > 0.4 have been used for palaeotemperature reconstructions71,117,129. In recent years, it has been shown that in situ-produced brGDGTs tend to be characterized by higher abundances of cyclic brGDGTs, resulting in high values for the #ringstetra index, and it has been suggested that #ringstetra values >0.7 are indicative of predominant in situ production of branched GDGTs149. Some of the new samples reported here, as well as some of the samples published in previous studies that are included in our compilation, have BIT values >0.4. However, some of the samples with BIT values >0.4 also have values for #ringstetra index >0.7, indicating that the brGDGTs were produced in situ, rather than transported from terrestrial soils. In the calculation of the latitudinal SST gradient, we exclude samples with BIT > 0.4 if the #ringstetra was <0.7 (178 samples) to avoid potential influences of terrestrial GDGTs on the estimated SST (see Extended Data Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 2 and code at https://github.com/audersea/paper_2022_nature). However, we note that there are no substantial differences in the SST gradient if all the samples with BIT > 0.4 are included in the calculation (Supplementary Data 2), suggesting that the potential influence of terrestrial GDGTs on the estimated SST is probably minimal despite the high BIT values.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41586-022-05017-0.

Supplementary information

FB-δ15N and FB-N content data. Sheets titled ‘DSDP 516’, ‘ODP 872’ contain all species-specific, genus-specific and mixed-taxa foraminifer-bound δ15N and FB-N content measurements from DSDP Site 516 and ODP Site 872, respectively, plotted in Figs. 2 and 3 and Extended Data Fig. 1. Sheet titled ‘ODP 1211’ contains mixed-taxa FB-δ15N and FB-N content measurements from ODP Site 1211, plotted in Extended Data Fig. 1. Sheets titled ‘ODP 1209’ and ‘ODP 1263’ contain genus-specific and mixed-taxa FB-δ15N and FB-N content measurements from ODP Sites 1209 and 1263, respectively, measured by ref. 18 with revised age models, plotted in Figs. 2 and 3 and Extended Data Fig. 1. The sheet titled ‘d15N gradient’ contains the calculated nitrogen isotope gradient between the Pacific and the Atlantic plotted in Figs. 2 and 3 and Extended Data Fig. 4.

TEX86 data measured in this study (ODP/DSDP Sites 516, 588, 667, 704, 730, 754, 1146 and 1263) and compilation of all published marine TEX86 records. This table contains all GDGTs measurements, calculated indices, temperatures and gradients.

Applied age models for ODP/DSDP Sites 516, 588, 667, 690, 704, 730, 738, 754, 1146, 1209, 1211 and 1263 with biostratigraphic (calcareous nannoplankton and foraminifer) and magnetostratigraphic datums adjusted to the GTS12 timescale.

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by the Max Planck Society (MPG), SNSF mobility grant P2EZP2_200000 and the Tuttle Fund of the Department of Geosciences, Princeton University. Sediment samples for this study were provided by the International Ocean Discovery Program. We acknowledge M. Schmitt, F. Rubach, B. Hinnenberg and S. Neugebauer for laboratory assistance. We also thank N. Shah for programming support. We thank C. Deutsch for discussions.

Extended data figures and tables

Author contributions

A.A. and A.M.-G. designed the study. A.A. measured foraminifer-bound nitrogen isotopes and organic biomarkers in the lab of A.M.-G. A.A., D.M.S. and A.M.-G. wrote the manuscript. B.T. and P.-R.E. contributed to sample preparation and foraminifer ecology, supervised by R.S. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and provided input to the final manuscript at different stages of the project.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Babette Hoogakker, Bernhard Naafs, Rebecca Robinson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Data availability

The datasets are available in Supplementary Data 1–3 and the PANGAEA database (10.1594/PANGAEA.943130).

Code availability

The code used for filtering, smoothing and gradient calculations for the SST and δ15N datasets is available on GitHub (https://github.com/audersea/Auderset_etal_2022_nature).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alexandra Auderset, Email: a.auderset@mpic.de.

Alfredo Martínez-García, Email: a.martinez-garcia@mpic.de.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41586-022-05017-0.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41586-022-05017-0.

References

- 1.Stramma L, Johnson GC, Sprintall J, Mohrholz V. Expanding oxygen-minimum zones in the tropical oceans. Science. 2008;320:655–658. doi: 10.1126/science.1153847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidtko S, Stramma L, Visbeck M. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature. 2017;542:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto A, et al. Global deep ocean oxygenation by enhanced ventilation in the Southern Ocean under long‐term global warming. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2015;29:1801–1815. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takano Y, Ito T, Deutsch C. Projected centennial oxygen trends and their attribution to distinct ocean climate forcings. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2018;32:1329–1349. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu W, Primeau F, Keith Moore J, Lindsay K, Randerson JT. Reversal of increasing tropical ocean hypoxia trends with sustained climate warming. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2018;32:551–564. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frölicher T, et al. Contrasting upper and deep ocean oxygen response to protracted global warming. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2020;34:e2020GB006601. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keeling RF, Körtzinger A, Gruber N. Ocean deoxygenation in a warming world. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2010;2:199–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westerhold T, et al. An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years. Science. 2020;369:1383–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.aba6853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen J, Sato M, Russell G, Kharecha P. Climate sensitivity, sea level and atmospheric carbon dioxide. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013;371:20120294. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2012.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anagnostou E, et al. Changing atmospheric CO2 concentration was the primary driver of early Cenozoic climate. Nature. 2016;533:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature17423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosdian SM, et al. Constraining the evolution of Neogene ocean carbonate chemistry using the boron isotope pH proxy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018;498:362–376. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller KG, et al. Cenozoic sea-level and cryospheric evolution from deep-sea geochemical and continental margin records. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz1346. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke KD, et al. Pliocene and Eocene provide best analogs for near-future climates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2018;115:13288–13293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809600115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cline J, Kaplan I. Isotopic fractionation of dissolved nitrate during denitrification in the eastern tropical North Pacific Ocean. Mar. Chem. 1975;3:271–299. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandes JA, Devol AH. A global marine‐fixed nitrogen isotopic budget: implications for Holocene nitrogen cycling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2002;16:67-1–67-14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altabet MA, et al. The nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry of sinking particles from the margin of the Eastern North Pacific. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1999;46:655–679. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren H, et al. Foraminiferal isotope evidence of reduced nitrogen fixation in the ice age Atlantic Ocean. Science. 2009;323:244–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1165787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kast ER, et al. Nitrogen isotope evidence for expanded ocean suboxia in the early Cenozoic. Science. 2019;364:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren H, Sigman DM, Thunell RC, Prokopenko MG. Nitrogen isotopic composition of planktonic foraminifera from the modern ocean and recent sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2012;57:1011–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigman, D. M. & Fripiat, F. in Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences 3rd edn (eds Kirk Cochran, J., Bokuniewicz, H. J. & Yager, P. L.) 263–278 (Academic, 2019).

- 21.Schouten S, Hopmans EC, Schefuß E, Damste JSS. Distributional variations in marine crenarchaeotal membrane lipids: a new tool for reconstructing ancient sea water temperatures? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002;204:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bindoff, N. L. et al. in IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) Ch. 5, 477–587 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

- 23.Bialik OM, Frank M, Betzler C, Zammit R, Waldmann ND. Two-step closure of the Miocene Indian Ocean Gateway to the Mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:8842. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagabrielle Y, Goddéris Y, Donnadieu Y, Malavieille J, Suarez M. The tectonic history of Drake Passage and its possible impacts on global climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009;279:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhnt, W., Holbourn, A., Hall, R., Zuvela, M. & Käse, R. in Continent-Ocean Interactions within East Asian Marginal Seas Vol. 149 (eds Clift, P., Kuhnt, W., Wang, P. & Hayes, D.) 299–320 (American Geophysical Union, 2004).

- 26.O’Dea A, et al. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600883. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fyke JG, D’Orgeville M, Weaver AJ. Drake Passage and Central American Seaway controls on the distribution of the oceanic carbon reservoir. Glob. Planet. Change. 2015;128:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller KG, Wright JD, Fairbanks RG. Unlocking the ice house: Oligocene‐Miocene oxygen isotopes, eustasy, and margin erosion. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1991;96:6829–6848. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren H, et al. Impact of glacial/interglacial sea level change on the ocean nitrogen cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2017;114:E6759–E6766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701315114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gnanadesikan A, Russell J, Zeng F. How does ocean ventilation change under global warming. Ocean Sci. 2007;3:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vecchi GA, et al. Weakening of tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation due to anthropogenic forcing. Nature. 2006;441:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nature04744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Douglas PM, et al. Pronounced zonal heterogeneity in Eocene southern high-latitude sea surface temperatures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6582–6587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321441111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsui H, et al. Vertical thermal gradient history in the eastern equatorial Pacific during the early to middle Miocene: implications for the equatorial thermocline development. Paleoceanography. 2017;32:729–743. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanden Berg MD, Jarrard RD. Cenozoic mass accumulation rates in the equatorial Pacific based on high‐resolution mineralogy of Ocean Drilling Program Leg 199. Paleoceanography. 2004;19:PA2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broecker WS. Ocean chemistry during glacial time. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1982;46:1689–1705. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarmiento JL, Toggweiler J. A new model for the role of the oceans in determining atmospheric pCO2. Nature. 1984;308:621–624. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shevenell AE, Kennett JP, Lea DW. Middle Miocene southern ocean cooling and Antarctic cryosphere expansion. Science. 2004;305:1766–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1100061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shevenell, A. E., Kennett, J. P. & Lea, D. W. Southern Ocean Middle Miocene ODP1171 Foraminifer Stable Isotope and Mg/Ca Data. IGBP PAGES/World Data Center for Paleoclimatology, Data Contribution Series # 2006-061, NOAA/NCDC Paleoclimatology Program (2006).

- 39.Wright, J. D. & Miller, K. G. in The Antarctic Paleoenvironment: A Perspective on Global Change, Part Two (eds Kennett, J. P. & Warnke, D. A.) 1–25 (American Geophysical Union, 1993).

- 40.Schneider LJ, Bralower TJ, Kump LR. Response of nannoplankton to early Eocene ocean destratification. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2011;310:152–162. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilting AK, Kump LR, Bralower TJ. Variations in the oceanic vertical carbon isotope gradient and their implications for the Paleocene‐Eocene biological pump. Paleoceanography. 2008;23:PA3222. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hague AM, et al. Convection of North Pacific deep water during the early Cenozoic. Geology. 2012;40:527–530. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burls NJ, et al. Active Pacific meridional overturning circulation (PMOC) during the warm Pliocene. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1700156. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker JC, Hays P, Kasting JF. A negative feedback mechanism for the long‐term stabilization of Earth’s surface temperature. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 1981;86:9776–9782. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sigman DM, et al. The Southern Ocean during the ice ages: a review of the Antarctic surface isolation hypothesis, with comparison to the North Pacific. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2021;254:106732. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francois R, et al. Contribution of Southern Ocean surface-water stratification to low atmospheric CO2 concentrations during the last glacial period. Nature. 1997;389:929–935. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaccard SL, Galbraith ED, Martínez-García A, Anderson RF. Covariation of deep Southern Ocean oxygenation and atmospheric CO2 through the last ice age. Nature. 2016;530:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nature16514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoogakker BA, et al. Glacial expansion of oxygen-depleted seawater in the eastern tropical Pacific. Nature. 2018;562:410–413. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deutsch C, Brix H, Ito T, Frenzel H, Thompson L. Climate-forced variability of ocean hypoxia. Science. 2011;333:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1202422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barker, P. F. et al. Site 516: Rio Grande Rise. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Vol. 72, 155–338. 10.2973/dsdp.proc.72.105.1983 (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1980).

- 51.Premoli Silva, I., Haggerty, J. & Rack, F. Site 872. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Initial Reports, Vol. 144, 105–144. 10.2973/odp.proc.ir.143.105.1993 (Texas A&M Univ., 1993).

- 52.van Hinsbergen DJ, et al. A paleolatitude calculator for paleoclimate studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bralower, T. J., Premoli Silva, I. & Malone, M. Leg 198 summary. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Initial Reports, Vol. 198, 1–148. 10.2973/odp.proc.ir.198.101.2002 (Texas A&M Univ., 2002).

- 54.Schlitzer, R. Data analysis and visualization with Ocean Data View. CMOS Bull. SCMO43, 9–13 (2015).

- 55.Garcia, H. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2018: product documentation. A. Mishonov, Technical Editor (2019).

- 56.Costa KM, et al. No iron fertilization in the equatorial Pacific Ocean during the last ice age. Nature. 2016;529:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature16453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berggren, W. A., Aubry, M. P. & Hamilton, N. in Neogene magnetobiostratigraphy of Deep Sea Drilling Project Site 516 (Rio Grande Rise, South Atlantic). Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Vol. 72, 675–706. 10.2973/dsdp.proc.72.130.1983 (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1983).

- 58.Hess J, Stott LD, Bender ML, Kennett JP, Schilling JG. The Oligocene marine microfossil record: age assessments using strontium isotopes. Paleoceanography. 1989;4:655–679. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei W, Wise Jr SW. Paleogene calcareous nannofossil magnetobiochronology: results from South Atlantic DSDP Site 516. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1989;14:119–152. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. & Ogg, G. (eds) The Geologic Time Scale 2012 (Elsevier, 2012).

- 61.Florindo F, et al. New magnetobiostratigraphic chronology and paleoceanographic changes across the Oligocene‐Miocene boundary at DSDP Site 516 (Rio Grande Rise, SW Atlantic) Paleoceanography. 2015;30:659–681. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bryan, W. B. & Duncan, R. A. Age and provenance of clastic horizons from Hole 516F. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Vol. 72, 475–477. 10.2973/dsdp.proc.72.118.1983 (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1983).

- 63.Hamilton, N. Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary studies at Deep Sea Drilling Project Site 516, Rio Grande Rise, South Atlantic: a synthesis. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Vol. 72, 949–952. 10.2973/dsdp.proc.72.150.1983 (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1983).

- 64.Pearson, G., Premoli Silva, I., Haggerty, J. A. & Shipboard Scientific Party (PANGAEA, 2005).

- 65.Pearson, P. N. Planktonic foraminifer biostratigraphy and the development of pelagic caps on guyots in the Marshall Islands Group. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 144, 21–59. (Texas A&M Univ., 1995).

- 66.Westerhold T, Röhl U, Donner B, Zachos JC. Global extent of early Eocene hyperthermal events: a new Pacific benthic foraminiferal isotope record from Shatsky Rise (ODP Site 1209) Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2018;33:626–642. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malone, M. J., Bralower, T. J., Premoli Silva, I. & Shipboard Scientific Party. Paleontological investigation on planktonic foraminifers of ODP Hole 144-872C (PANGAEA, 2005).

- 68.Pagani M, Arthur MA, Freeman KH. Miocene evolution of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Paleoceanography. 1999;14:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruddiman, W. F., Sarnthein, M. & Shipboard Scientific Party. P-wave velocity (PWL whole-core system) on ODP Hole 108-664B (PANGAEA, 2005).

- 70.Ciesielski, P. F., Kristoffersen, Y. & Shipboard Scientific Party. P-wave velocity (PWS split-core system) on ODP Hole 114-698A (PANGAEA, 2005).

- 71.Leutert T, Auderset A, Martínez-Garci A, Modestou S, Meckler AN. Coupled Southern Ocean cooling and Antarctic ice sheet expansion during the middle Miocene. Nat. Geosci. 2020;13:634–639. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sangiorgi F, Quaijtaal W, Donders TH, Schouten S, Louwye S. Middle Miocene temperature and productivity evolution at a Northeast Atlantic shelf site (IODP U1318, Porcupine Basin): global and regional changes. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2021;36:e2020PA004059. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prell, W. L., Niitsuma, N. & al, E. Site 730. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Initial Reports, Vol. 117, 555–584. 10.2973/odp.proc.ir.117.117.1989 (Texas A&M Univ., 1989).

- 74.Peirce, J. W., Weissel, J. K. & Shipboard Scientific Party. Hole/core summary of ODP Site 121-757. (PANGAEA, 2005).

- 75.Nathan, S. A. & Leckie, R. M. Miocene planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy of Sites 1143 and 1146, ODP Leg 184, South China Sea. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 184, 1–43. 10.2973/odp.proc.sr.184.219.2003 (Texas A&M Univ., 2003).

- 76.Censarek, B. & Gersonde, R. Data report: relative abundance and stratigraphic ranges of selected diatoms from Miocene sections at ODP Sites 689, 690, 1088, and 1092 (Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean). Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 177, 1–14. 10.2973/odp.proc.sr.177.119.2003 (Texas A&M Univ., 2003).

- 77.Mehra OP, Jackson ML. Iron oxide removal from soils and clays by a dithionite–citrate system buffered with sodium bicarbonate. Clay Miner. 1960;7:317–327. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Braman RS, Hendrix SA. Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium(III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chem. 1989;61:2715–2718. doi: 10.1021/ac00199a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sigman D, et al. A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:4145–4153. doi: 10.1021/ac010088e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Casciotti KL, Sigman DM, Hastings MG, Böhlke J, Hilkert A. Measurement of the oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate in seawater and freshwater using the denitrifier method. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:4905–4912. doi: 10.1021/ac020113w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McIlvin MR, Casciotti KL. Technical updates to the bacterial method for nitrate isotopic analyses. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:1850–1856. doi: 10.1021/ac1028984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weigand MA, Foriel J, Barnett B, Oleynik S, Sigman DM. Updates to instrumentation and protocols for isotopic analysis of nitrate by the denitrifier method. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2016;30:1365–1383. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Straub M, et al. Changes in North Atlantic nitrogen fixation controlled by ocean circulation. Nature. 2013;501:200–203. doi: 10.1038/nature12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martínez-García A, et al. Iron fertilization of the Subantarctic Ocean during the last ice age. Science. 2014;343:1347–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1246848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leichliter JN, et al. Nitrogen isotopes in tooth enamel record diet and trophic level enrichment: results from a controlled feeding experiment. Chem. Geol. 2021;563:120047. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Auderset A, Schmitt M, Martínez-García A. Simultaneous extraction and chromatographic separation of n-alkanes and alkenones from glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers via selective Accelerated Solvent Extraction. Org. Geochem. 2020;143:103979. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Patwardhan AP, Thompson DH. Efficient synthesis of 40-and 48-membered tetraether macrocyclic bisphosphocholines. Organic Letters. 1999;1:241–244. doi: 10.1021/ol990567o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hopmans EC, Schouten S, Damsté JSS. The effect of improved chromatography on GDGT-based palaeoproxies. Org. Geochem. 2016;93:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smart SM, et al. Ground-truthing the planktic foraminifer-bound nitrogen isotope paleo-proxy in the Sargasso Sea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2018;235:463–482. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smart SM, et al. The nitrogen isotopic composition of tissue and shell‐bound organic matter of planktic foraminifera in Southern Ocean surface waters. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems. 2020;21:e2019GC008440. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ai XE, et al. Southern Ocean upwelling, Earth’s obliquity, and glacial-interglacial atmospheric CO2 change. Science. 2020;370:1348–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.abd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Auderset A, et al. Gulf Stream intensification after the early Pliocene shoaling of the Central American Seaway. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2019;520:268–278. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bijl PK, et al. Early Palaeogene temperature evolution of the southwest Pacific Ocean. Nature. 2009;461:776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature08399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bijl PK, et al. Eocene cooling linked to early flow across the Tasmanian Gateway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2013;110:9645–9650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220872110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boscolo Galazzo F, et al. The middle Eocene climatic optimum (MECO): a multiproxy record of paleoceanographic changes in the southeast Atlantic (ODP Site 1263, Walvis Ridge) Paleoceanography. 2014;29:1143–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Burgess CE, et al. Middle Eocene climate cyclicity in the southern Pacific: implications for global ice volume. Geology. 2008;36:651–654. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Caley T, et al. High-latitude obliquity as a dominant forcing in the Agulhas current system. Clim. Past. 2011;7:1285–1296. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cramwinckel MJ, et al. A warm, stratified, and restricted Labrador Sea across the middle Eocene and its climatic optimum. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2020;35:e2020PA003932. doi: 10.1029/2020PA003932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cramwinckel MJ, et al. Synchronous tropical and polar temperature evolution in the Eocene. Nature. 2018;559:382–386. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Bar MW, Rampen SW, Hopmans EC, Damsté JSS, Schouten S. Constraining the applicability of organic paleotemperature proxies for the last 90 Myrs. Org. Geochem. 2019;128:122–136. [Google Scholar]

- 101.De Vleeschouwer D, Petrick BF, Martínez‐García A. Stepwise weakening of the pliocene Leeuwin current. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019;46:8310–8319. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Douglas PM, et al. Pronounced zonal heterogeneity in Eocene southern high-latitude sea surface temperatures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2014;111:6582–6587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321441111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Frieling J, et al. Extreme warmth and heat-stressed plankton in the tropics during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1600891. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Frieling J, Sluijs A. Towards quantitative environmental reconstructions from ancient non-analogue microfossil assemblages: ecological preferences of Paleocene–Eocene dinoflagellates. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018;185:956–973. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guitián J, et al. Midlatitude temperature variations in the Oligocene to early Miocene. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2019;34:1328–1343. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hartman JD, Sangiorgi F, Escutia C. Paleoceanography and ice sheet variability offshore Wilkes Land, Antarctica – Part 3: insights from Oligocene–Miocene TEX86-based sea surface temperature reconstructions. Clim. Past. 2018;14:1275–1297. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hayes CT, et al. A stagnation event in the deep South Atlantic during the last interglacial period. Science. 2014;346:1514–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.1256620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hollis CJ, et al. Tropical sea temperatures in the high-latitude South Pacific during the Eocene. Geology. 2009;37:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hollis CJ, et al. Early Paleogene temperature history of the Southwest Pacific Ocean: reconciling proxies and models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012;349:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Inglis GN, et al. Descent toward the Icehouse: Eocene sea surface cooling inferred from GDGT distributions. Paleoceanography. 2015;30:1000–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Keating-Bitonti CR, Ivany LC, Affek HP, Douglas P, Samson SD. Warm, not super-hot, temperatures in the early Eocene subtropics. Geology. 2011;39:771–774. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lawrence K, et al. Comparison of late Neogene Uk′37 and TEX86 paleotemperature records from the eastern equatorial Pacific at orbital resolution. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2020;35:e2020PA003858. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Leutert TJ, Auderset A, Martínez-García A, Modestou S, Meckler AN. Coupled Southern Ocean cooling and Antarctic ice sheet expansion during the middle Miocene. Nat. Geosci. 2020;13:634–639. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu Z, et al. Global cooling during the Eocene-Oligocene climate transition. Science. 2009;323:1187–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1166368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Naafs BDA, Voelker A, Karas C, Andersen N, Sierro F. Repeated near‐collapse of the Pliocene sea surface temperature gradient in the North Atlantic. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2020;35:e2020PA003905. [Google Scholar]

- 116.O’Brien CL, et al. High sea surface temperatures in tropical warm pools during the Pliocene. Nat. Geosci. 2014;7:606–611. [Google Scholar]

- 117.O’Brien CL, et al. The enigma of Oligocene climate and global surface temperature evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2020;117:25302–25309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003914117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pearson PN, et al. Stable warm tropical climate through the Eocene Epoch. Geology. 2007;35:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Petrick B, et al. Glacial Indonesian Throughflow weakening across the mid-Pleistocene climatic transition. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:16995. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Petrick B, et al. Oceanographic and climatic evolution of the southeastern subtropical Atlantic over the last 3.5 Ma. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018;492:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rommerskirchen F, Condon T, Mollenhauer G, Dupont L, Schefus E. Miocene to Pliocene development of surface and subsurface temperatures in the Benguela Current system. Paleoceanography. 2011;26:PA3216. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sangiorgi F, et al. Southern Ocean warming and Wilkes Land ice sheet retreat during the mid-Miocene. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:317. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02609-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Śliwińska KK, Thomsen E, Schouten S, Schoon PL, Heilmann-Clausen C. Climate- and gateway-driven cooling of Late Eocene to earliest Oligocene sea surface temperatures in the North Sea Basin. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4458. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41013-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sluijs A, et al. Subtropical Arctic Ocean temperatures during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum. Nature. 2006;441:610–613. doi: 10.1038/nature04668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sluijs A, et al. Late Paleocene–early Eocene Arctic Ocean sea surface temperatures: reassessing biomarker paleothermometry at Lomonosov Ridge. Clim. Past. 2020;16:2381–2400. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sluijs A, et al. Environmental precursors to rapid light carbon injection at the Palaeocene/Eocene boundary. Nature. 2007;450:1218–1221. doi: 10.1038/nature06400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Smith RA, et al. Plio‐Pleistocene Indonesian Throughflow variability drove eastern Indian Ocean sea surface temperatures. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2020;35:e2020PA003872. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Stokke EW, Jones MT, Tierney JE, Svensen HH, Whiteside JH. Temperature changes across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum – a new high-resolution TEX86 temperature record from the Eastern North Sea Basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020;544:116388. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Super JR, et al. North Atlantic temperature and pCO2 coupling in the early-middle Miocene. Geology. 2018;46:519–522. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Vickers ML, et al. Cold spells in the Nordic Seas during the early Eocene Greenhouse. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4713. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18558-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wade BS, et al. Multiproxy record of abrupt sea-surface cooling across the Eocene-Oligocene transition in the Gulf of Mexico. Geology. 2012;40:159–162. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wittkopp, F. Organic geochemical investigation of sediments in the Japan Sea: tracking paleoceanographic and paleoclimatic changes since the mid-Miocene (PANGAEA, 2017).

- 133.Zachos JC, et al. Extreme warming of mid-latitude coastal ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: inferences from TEX86 and isotope data. Geology. 2006;34:737–740. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhang YG, Pagani M, Liu ZH, Bohaty SM, DeConto R. A 40-million-year history of atmospheric CO2. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013;371:20130096. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2013.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhang YG, Pagani M, Liu Z. A 12-million-year temperature history of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Science. 2014;344:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1246172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhuang G, Pagani M, Zhang YG. Monsoonal upwelling in the western Arabian Sea since the middle Miocene. Geology. 2017;45:655–658. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kim J-H, et al. New indices and calibrations derived from the distribution of crenarchaeal isoprenoid tetraether lipids: implications for past sea surface temperature reconstructions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2010;74:4639–4654. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tierney JE, Tingley MP. A Bayesian, spatially-varying calibration model for the TEX86 proxy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014;127:83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Weijers JWH, Schouten S, Spaargaren OC, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Occurrence and distribution of tetraether membrane lipids in soils: implications for the use of the TEX86 proxy and the BIT index. Org. Geochem. 2006;37:1680–1693. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zhang YG, et al. Methane Index: a tetraether archaeal lipid biomarker indicator for detecting the instability of marine gas hydrates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011;307:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhang YG, Pagani M, Wang Z. Ring Index: a new strategy to evaluate the integrity of TEX86 paleothermometry. Paleoceanography. 2016;31:220–232. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hopmans EC, et al. A novel proxy for terrestrial organic matter in sediments based on branched and isoprenoid tetraether lipids. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004;224:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Peterse F, Nicol GW, Schouten S, Damsté JSS. Influence of soil pH on the abundance and distribution of core and intact polar lipid-derived branched GDGTs in soil. Org. Geochem. 2010;41:1171–1175. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Fietz S, Martínez‐Garcia A, Huguet C, Rueda G, Rosell‐Melé A. Constraints in the application of the Branched and Isoprenoid Tetraether index as a terrestrial input proxy. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2011;116:C10032. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Fietz S, et al. Co-variation of crenarchaeol and branched GDGTs in globally-distributed marine and freshwater sedimentary archives. Glob. Planet. Change. 2012;92:275–285. [Google Scholar]

- 146.De Jonge C, et al. Drastic changes in the distribution of branched tetraether lipids in suspended matter and sediments from the Yenisei River and Kara Sea (Siberia): implications for the use of brGDGT-based proxies in coastal marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015;165:200–225. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Xiao W, et al. Ubiquitous production of branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (brGDGTs) in global marine environments: a new source indicator for brGDGTs. Biogeosciences. 2016;13:5883–5894. [Google Scholar]