Highlights

-

•

HCW admissions were higher in wave 1 (48.6% of total HCW admissions) compared with wave 2 (32.0%).

-

•

HCWs were less likely to have mortality as an outcome (aOR 0.6; 95% CI 0.5–0.7).

-

•

Age, race, wave, sector, and province were risk factors for in-hospital mortality.

-

•

Weekly hospital admissions increased the risk of COVID-19 mortality for HCWs.

Key words: SARS-CoV-2, hospital surveillance, healthcare workers, hospital admissions, in-hospital mortality

Abstract

Objectives

This study describes the characteristics of admitted HCWs reported to the DATCOV surveillance system, and the factors associated with in-hospital mortality in South African HCWs.

Methods

Data from March 5, 2020 to April 30, 2021 were obtained from DATCOV, a national hospital surveillance system monitoring COVID-19 admissions in South Africa. Characteristics of HCWs were compared with those of non-HCWs. Furthermore, a logistic regression model was used to assess factors associated with in-hospital mortality among HCWs.

Results

In total, there were 169 678 confirmed COVID-19 admissions, of which 6364 (3.8%) were HCWs. More of these HCW admissions were accounted for in wave 1 (48.6%; n = 3095) than in wave 2 (32.0%; n = 2036). Admitted HCWs were less likely to be male (28.2%; n = 1791) (aOR 0.3; 95% CI 0.3–0.4), in the 50–59 age group (33.1%; n = 2103) (aOR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–1.8), or accessing the private health sector (63.3%; n = 4030) (aOR 1.3; 95% CI 1.1–1.5). Age, comorbidities, race, wave, province, and sector were significant risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality.

Conclusion

The trends in cases showed a decline in HCW admissions in wave 2 compared with wave 1. Acquired SARS-COV-2 immunity from prior infection may have been a reason for reduced admissions and mortality of HCWs despite the more transmissible and more severe beta variant in wave 2.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020 and a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Wu and McGoogan, 2020; WHO 2020a). As of April 30, 2021, a total of 153 million COVID-19 cases had been reported globally, with 3.2 million deaths (Mike, 2021). In South Africa, the number of cumulative COVID-19 cases by April 30, 2021 was 1 581 210 with 54 350 deaths (NICD, 2020).

Healthcare workers (HCWs) have an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 because their work entails close contact with COVID-19 patients (Zhang et al., 2022). WHO has estimated that up to 14% of COVID-19 cases globally have been in HCWs (Rees et al., 2021). In South Africa, there are an estimated 1.25 million HCWs from both the private and public sectors (Charles, 2021). Many factors can increase the risk of COVID-19 transmission among HCWs, including: lack of protective resources during treatment of patients, such as adequate personnel protective equipment (PPE), masks, and gloves; inappropriate training on specimen/patient handling and infection control; and appropriate infection control strategies not being properly implemented in some healthcare facilities (Mhango et al., 2020; Bielicki et al., 2020). Aside from the risks of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 in the workplace, HCWs may also be infected in their communities.

Several studies have shown poorer COVID-19 outcomes relating to older age, male sex, and a history of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, malignancy, chronic cardiac diseases, and asthma (Barek et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020). South Africa has a high prevalence of non-communicable diseases, including diabetes (12.8%), hypertension (41.6–54%), and obesity (68% of females, 31% of males) (Parker et al., 2020). In 2017, a national survey of HIV prevalence showed that about 14.6% of the South African population was living with HIV (Marinda et al., 2020); additionally, 11–12% of HCWs in South Africa are infected with HIV (Grobler et al., 2016). The prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) in South Africa is 3.6% (WHO, 2020b); in addition, high rates of TB infection have been recorded among South African HCWs, with an active TB disease incidence of 1.13–1.47% (Basera et al., 2017; Grobler et al., 2016).

There is limited published information describing COVID-19 admissions among HCWs in South Africa, and few studies have explored the risk factors for in-hospital mortality due to COVID-19 among South African HCWs. Our study aimed to describe the characteristics of admitted HCWs reported to the DATCOV surveillance system, and to assess factors associated with in-hospital mortality among HCWs in South Africa.

METHODS

Study design

This was a prospective surveillance study of HCWs and non-HCWs diagnosed with COVID-19 disease across public and private health facilities in South Africa, from March 5, 2020 to April 30, 2021.

Data sources

The DATCOV national hospital surveillance system was established in March 2020 by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases to monitor COVID-19 hospital admissions in South Africa (Jassat et al., 2021a). Full coverage was achieved in October 2020, with all hospitals reporting COVID-19 cases upon admission into the surveillance system. By the end of April 2021, 625 hospitals (375 from the public sector and 250 from the private sector) had reported COVID-19 admissions among HCWs to the DATCOV surveillance system. The supplementary material provides further information on DATCOV data management and data quality checks.

Study population

This study included patients of working age (20–65 years) who had reported a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 and were admitted to public or private health facilities across South Africa between March 5, 2020 and April 30, 2021. Admitted patients were asked if they were employed as HCWs (coded as ‘1’ for patients who reported ‘yes’) or non-HCWs (coded as ‘0’ for patients who reported ‘no’) when reporting to DATCOV. Patients admitted as HCWs were further classified as administrators and porters, doctors, nurses, allied healthcare workers, laboratory staff, or paramedics. Unknown HCW occupations were labelled as ‘other’. A sample size calculation was not carried for the study, because the study included all available data on admitted patients recorded on the DATCOV surveillance system.

Case definition and identification

The case definition used was based on a definition released by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases and the National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa in their guidelines for case-finding, diagnosis, and public health response in South Africa, in a document published as ‘Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)’ (NICD, 2022).

For our study, only laboratory-confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection, based on positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays or positive antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2, were included in the analysis. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality was defined as death occurring during the hospital stay and relating to COVID-19. COVID-19-related deaths reported on the surveillance programme where confirmed by contacting the hospital from which each death was recorded and cross-checking the patient ID against the hospital records and death registry. Other causes of death not related to COVID-19 infection were excluded in the analysis, as well as deaths occurring after discharge.

Study variables

Potential risk factors and covariates included in this study were age, categorized into five groups (20–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and 60–65 years), sex, race or ethnicity, and comorbid diseases (hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal diseases, chronic pulmonary asthma, chronic cardiovascular diseases, current and past tuberculosis (TB), HIV, and obesity).

The study duration was divided into five wave periods: pre-wave 1 (March 5 to June 6, 2020); wave 1 (June 7 to August 29, 2020); post-wave 1 (August 30 to November 21, 2020), wave 2 (November 22, 2020 to February 6, 2021), and post-wave 2 (February 7 to April 30, 2021). The variable ‘weekly national number’, comprising three categories, was generated and used as a proxy to measure the load of COVID-19 hospital admissions, where admissions < 3500 were described as ‘low admissions’, 3500–7999 as ‘moderate admissions’, and > 8000 as ‘high admissions’.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to summarize variables. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression models were implemented to: (a) compare the characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 HCWs and non-HCWs; and (b) assess risk factors for COVID-19 in-hospital mortality among HCWs.

For the final adjusted model, a maximum likelihood test was used to include variables at the 5% level. Variables that were statistically significant and those considered important according to the existing literature were included in the final model. Sector and province were adjusted for in the regression model, which assessed the association of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality with potential risk factors in order to account for the differences in hospital admissions and in the quality of care received in the private and public sectors within provinces.

The results were presented as unadjusted odds ratios (OR) in the univariate analysis for all covariates and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) in the multivariate analysis, with 95% confidence intervals. To investigate the effects of missing observations on the final model, a model using the variable with more than 50% missing was fitted, which was compared with the model without the variable. Data analysis was conducted using STATA 15 (Stata Corp® College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of HCW and non-HCW patients admitted with COVID-19

In total, 169 678 admissions relating to COVID-19 had been reported in South Africa by April 30, 2021, with 6364 (3.8%) of the patients reported as HCWs. Among the admitted HCWs 1330/6364 (21.0%) were nurses, 131/6364 (2.1%) doctors, 508/6364 (8.0%) administrators and porters, 191/6364 (3.0%) allied healthcare workers, laboratory staff 56/6364 (0.9%), and paramedics, 24/6364 (0.4%); 4124/6364 (64.8%) were classified as other (unknown occupation category).

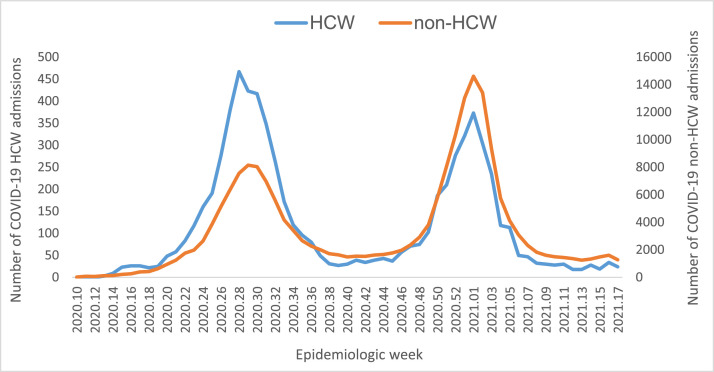

As of April 30, 2021, South Africa had experienced two waves of COVID-19, the first peaking in weeks 28–29 of 2020 (July 11 to July 18, 2021) and the second peaking in week 1 of 2021 (December 26, 2020 to January 2, 2021) (Figure 1). Of all reported admissions among HCW workers in the period March 5 to November 21, 2020, 6.6% (418/6364) were in pre-wave 1, 48.6% (3095/6364) in wave 1, and 7.9% (500/6364) in post-wave 1 period. With regards to wave 2, 32% (2036/6364) and 4.9% (315/6364) of the HCW admissions were reported in wave 2 and post-wave 2, respectively. Of all admissions for non-HCWs, 36.7% (59 968/163 314) were reported in pre-wave 1, wave 1 and post-wave 1, and 63.3% (103 346/163 314) in wave 2 and post-wave 2.

Figure 1.

Number of COVID-19 admissions reported in health care workers and non-healthcare workers by epidemiological week, 5 March 2020-30 April 2021, n= 169,678.

There were 30 191 (17.8%) deaths recorded in total, with a CFR of 9.7% (603/6220) for HCWs and 18.7% (29 588/157 826) for non-HCWs. A multivariate analysis comparing characteristics of HCWs with non-HCWs showed that HCWs admitted with COVID-19 were less likely to be males (aOR 0.3; 95% CI 0.3–0.4) and to have mortality as outcome (aOR 0.6; 95% CI 0.5–0.7). HCWs were more likely to be admitted in the private sector (aOR 1.3; 95% CI 1.1–1.5), in the Eastern Cape (aOR 1.9; 95% CI 1.5–2.4), Gauteng (aOR 2.1; 95% CI 1.6–2.6), Kwa-Zulu Natal (aOR 2.4; 95% CI 1.9–2.6), Limpopo (aOR 1.7; 95% CI 1.2–2.6), and North West (aOR 1.8; 95% CI 2.1–3.8) provinces compared with the Western Cape.

Compared with non-HCW admissions, HCW hospital admissions were more likely to occur in the 30–39 years (aOR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–1.9), 40–49 years (aOR 1.6; 95% CI 1.2–2.0), and 50–59 years (aOR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–1.8) age groups compared with 20–29 years, and in pre-wave 1 (aOR 3.0; 95% CI 2.4–3.7) and wave 1 (aOR 2.1; 95% CI 1.8–2.5) compared with wave 2. HCWs were more likely to have obesity (aOR 1.8; 95% CI 1.5–2.1) and asthma (aOR 1.3; 95% CI 1.0–1.5) as existing comorbidities, and less likely to have HIV (aOR 0.7; 95% CI 0.6–0.9) and chronic kidney diseases (aOR 0.2; 95% CI 0.1–0.4).

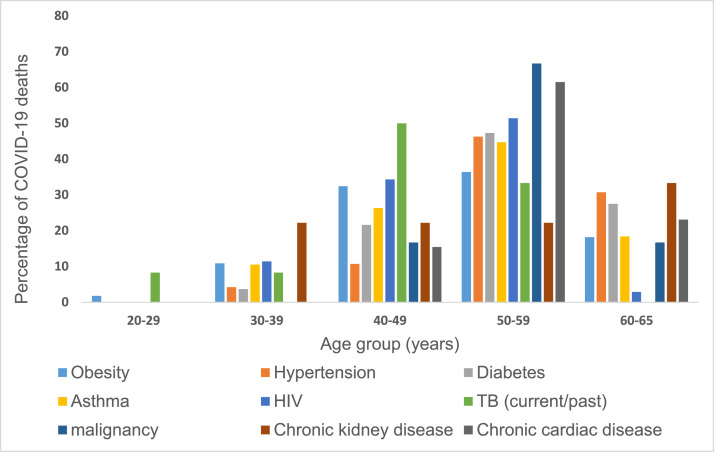

Comorbidities reported for COVID-19 deaths

Comorbidities reported among HCWs who died of COVID-19, across all age groups, are shown in Figure 2. Most COVID-19 related deaths were reported in the 50–59 years and 40–49 years age groups, with malignancy and chronic cardiac diseases as commonly reported comorbidities in the 50–59 years age group, and TB, HIV, and obesity commonly reported comorbidities in the 40–49 years age group Table 1.

Figure 2.

Percentages of reported comorbid diseases among healthcare workers (HCWs) who died from COVID-19, stratified by age-group between from 5 March 2020 through 30 April 2021, South Africa, n=603.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitalized HCWs and non-HCWs with COVID-19, South Africa; March 5, 2020 to April 30 2021 (N = 169 678).

| Characteristic | HCWs (N, %)N = 6364 | Non-HCWs (N, %)N = 163 314 | OR | p-value | aOR | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 4571 (71.9) | 90 295 (55.4) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Male | 1791 (28.2) | 72 760 (44.6) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | < 0.001 | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) | < 0.001 |

| Age group (in years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | 464 (7.3) | 15 540 (9.5) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 30–39 | 1341 (21.1) | 31 129 (19.1) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | < 0.001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.005 |

| 40–49 | 1769 (27.8) | 38 715 (23.7) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | < 0.001 | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | < 0.001 |

| 50–59 | 2103 (33.1) | 49 927 (30.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | < 0.001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.005 |

| 60–65 | 687 (10.8) | 28 003 (17.2) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | < 0.001 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.139 |

| Race (n/N, %) | ||||||

| Black | 3865/6273 (61.6) | 89 298/162 518 (55.0) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Mixed race | 387/6273 (6.2) | 7562/162 518 (4.7) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.002 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.799 |

| Indian | 457/6273 (7.3) | 6043/162 518 (3.7) | 1.7 (1.6–1.9) | < 0.001 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.296 |

| White | 648/6273 (10.3) | 7054/162 518 (4.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4 | < 0.001 | 1.4 (1.0–1.7) | 0.014 |

| Other | 916/6273 (14.6) | 52 561/162 518 (32.3) | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | < 0.001 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Sector | ||||||

| Public | 2334 (36.7) | 84 316 (51.6) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Private | 4030 (63.3) | 78 998 (48.4) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | < 0.001 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Province | ||||||

| Western Cape | 721 (11.3) | 32 140 (19.7) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Eastern Cape | 891 (14.0) | 19 601 (12.0) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | < 0.001 | 1.8 (1.5–2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Free State | 276 (4.3) | 9646 (5.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.001 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.784 |

| Gauteng | 2045 (32.1) | 44 504 (27.3) | 2.0 (1.9–2.2) | < 0.001 | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Kwa-Zulu Natal | 1658 (26.1) | 31 612 (19.4) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | < 0.001 | 2.3 (1.9–2.9) | < 0.001 |

| Limpopo | 138 (2.2) | 6207 (3.8) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.924 | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | 0.002 |

| Mpumalanga | 144 (2.3) | 6753 (4.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.583 | 0.6 (0.4–1.2) | 0.178 |

| North West | 424 (6.7) | 9683 (5.9) | 2.0 (1.7–2.1) | < 0.001 | 2.8 (2.1–3.6) | < 0.001 |

| Northern Cape | 67 (1.1) | 3168 (1.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.648 | 1.5 (1.0–2.6) | 0.073 |

| Wave | ||||||

| Pre-wave 1 | 418 (6.6) | 7068 (4.3) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | < 0.001 | 3.0 (2.4–3.7) | < 0.001 |

| Wave 1 | 3095 (48.6) | 52 707 (32.3) | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | < 0.001 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Post-wave 1 | 500 (7.9) | 17 530 (10.7) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.725 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.040 |

| Wave 2 | 2036 (32.0) | 70 124 (42.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Post-wave 2 | 315 (4.9) | 15 885 (9.7) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.976 |

| Chronic diseases (n/N, %) | ||||||

| Obesity | ||||||

| No | 1398 (81.1) | 36 412 (88.2) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 325 (18.9) | 4857 (11.8) | 1.7 (1.5–1.9) | < 0.001 | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | 3318/5049 (65.7) | 79 728/118 636 (67.2) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 1731/5049 (34.3) | 38 908/118 636 (32.8) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.028 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.054 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 3852/4993 (77.2) | 86 727/116 665 (74.3) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 1141/4993 (22.9) | 29 938/116 665 (25.7) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | < 0.001 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.187 |

| Asthma | ||||||

| No | 4543/4880 (93.1) | 104 936/111 741 (93.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 337/4880 (6.9) | 6805/111 741 (6.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.020 | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 0.014 |

| HIV | ||||||

| No | 4492/4807 (93.5) | 98 308/111 731 (88.0) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 315/4807 (6.6) | 13 423/111 731 (12.0) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | < 0.001 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | < 0.001 |

| TB (current/past) | ||||||

| No | 4751/4842 (98.1) | 105 661/110 877 (95.3) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 91/4842 (1.9) | 5216/110 877 (4.7) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | < 0.001 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.708 |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||

| No | 4778/4807 (99.4) | 106 527/108 836 (97.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 29/4807 (0.6) | 2309/108 836 (2.1) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | < 0.001 | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Malignancy | ||||||

| No | 4755/4779 (99.5) | 107 899/108 565 (99.34) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 24/4779 (0.5) | 666/108 565 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.334 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.396 |

| Pregnancy (n/N, %) | ||||||

| No | 6234/6364 (98.0) | 157 608/157 608 (96.1) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 130/6364 ((2.0) | 5706/16 314 (3.5) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | < 0.001 | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | < 0.001 |

| Admission outcome | ||||||

| Discharged alive | 5761 (90.3) | 128 238 (81.3) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Died | 603 (9.7) | 29 588 (18.7) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | < 0.001 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | < 0.001 |

Factors associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality among HCWs

On multivariate analysis (Table 2), risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality among HCWs were older age, high weekly load of hospital admissions, province, and history of comorbidities. The odds of HCW mortality increased with age, with HCWs aged 40–49 years (aOR 3.8; 95% CI 1.6–8.8), 50–59 years (aOR 4.7; 95% CI 2.0–10.9), and 60–65 years (aOR 9.8; 95% CI 4.2–22.9) having increased odds of mortality compared with HCWs aged 20–29 years.

Table 2.

Factors associated with COVID–19 in–hospital mortality among hospitalized HCWs in South Africa, March 5, 2020 to April 30, 2021.

| Characteristics | Case fatality ratio, n/N (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 390/4462 (8.7) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Male | 213/1756 (12.1) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | < 0.001 | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 0.144 |

| Age group (in years) | |||||

| 20–29 | 8/453 (1.8) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 30–39 | 47/1318 (3.6) | 2.1 (1.0–4.4) | 0.062 | 1.7 (0.7–4.1) | 0.229 |

| 40–49 | 142/1730 (8.2) | 4.9 (2.4–10.2) | < 0.001 | 3.8 (1.6–8.8) | 0.002 |

| 50–59 | 249/2047 (12.2) | 7.7 (3.8–15.6) | < 0.001 | 4.7 (2.0–10.9) | < 0.001 |

| 60–65 | 157/672 (23.4) | 16.9 (8.2–34.7) | < 0.001 | 9.8 (4.2–23.0) | < 0.001 |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 391/3758 (10.4) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Mixed race | 28/75 (37.3) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.074 | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.008 |

| Indian | 59/454 (13.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | 0.092 | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.329 |

| White | 68/635 (10.7) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 0.817 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.081 |

| Other | 48/911 (5.3) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | 0.911 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Administrators/porters | 35/497(7.0) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Allied healthcare | 25/183 (13.7) | 1.5 (0.7–2.9) | 0.279 | 1.6 (0.6–3.9) | 0.315 |

| Doctors | 24/126 (19.0) | 4.2 (2.2–8.0) | < 0.001 | 3.2 (1.4–7.7) | 0.008 |

| Nurses | 132/1271 (10.4) | 1.4 (0.9–2.4) | 0.160 | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 0.796 |

| Paramedics | 3/49 (6.1) | 0.8 (0.2–3.4) | 0.718 | 0.9 (0.2–4.3) | 0.858 |

| Other | 383/4071 (10.4) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 0.604 | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.484 |

| Wave | |||||

| Pre-wave 1 | 19/412 (4.6) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.015 | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) | 0.041 |

| Wave 1 | 274/3044 (9.0) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Post-wave 1 | 33/489 (6.7) | 0.8 (0.67–1.2) | 0.322 | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 0.386 |

| Wave 2 | 277/1999 (13.9) | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | < 0.001 | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.373 |

| Post-wave 2 | 29/276 (10.5) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 0.157 | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | 0.905 |

| Weekly national number | |||||

| Low, < 3500 | 166/1949 (8.5) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Medium, 3500–7999 | 270/2998 (9.0) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 0.142 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.385 |

| High, 8000–12499 | 167/1110(15.0) | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | < 0.001 | 1.5 (1.1–2.3) | 0.025 |

| Sector | |||||

| Private | 440/3967 (11.1) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Public | 163/2253 (7.2) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | < 0.001 | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.011 |

| Province | |||||

| Western Cape | 65/710 (9.2) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Eastern Cape | 134/872 (15.4) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | < 0.001 | 1.9 (1.3–2.9) | 0.003 |

| Free State | 19/251 (7.6) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.445 | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.516 |

| Gauteng | 142/2016 (7.0) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.069 | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.861 |

| Kwa–Zulu Natal | 176/1639 (10.7) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.246 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.895 |

| Limpopo | 19/130 (14.6) | 1.7 (0.9–2.9) | 0.059 | 2.5 (1.3–5.2) | 0.009 |

| Mpumalanga | 18/136 (13.2) | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.145 | 1.8 (0.8–3.7) | 0.117 |

| North West | 25/404 (6.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.089 | 0.7 (0.3–1.2) | 0.209 |

| Northern Cape | 5/62 (8.1) | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 0.774 | 1.3 (0.3–4.6) | 0.658 |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 276/3259 (8.5) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 283/1686 (16.8) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | < 0.001 | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.027 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 329/3779 (8.7) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 218/1111 (19.6) | 2.6 (2.1–3.1) | < 0.001 | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||

| No | 516/4690 (11.0) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 9/28 (32.1) | 3.8 (1.7–8.5) | 0.001 | 4.1 (1.6–10.0) | 0.002 |

| Malignancy | |||||

| No | 518/4674 (11.1) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 6/23 (26.1) | 2.8 (1.1–6.9) | 0.029 | 3.7 (1.1–7.2) | 0.014 |

| TB (current/past) | |||||

| No | 514/4665 (11.0) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 12/87 (13.8) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.473 | 2.2 (1.1–4.4) | 0.019 |

HCW job category had a significant role in COVID-19 mortality, with doctors found to have increased risk of COVID-19 mortality (aOR 3.2; 95% CI 1.4–7.7) compared with administrators/porters. The risk of mortality was increased among HCWs admitted in Limpopo (aOR 2.5; 95% CI 1.3–5.2) and Eastern Cape (aOR 1.9; 95% CI 1.3–2.9) provinces compared with those in the Western Cape. Weekly hospital admissions of ≥ 8000 increased the risk of hospital mortality among HCWs compared with low admission numbers (aOR 1.5; 95% CI 1.1–2.3). HCWs with comorbidities such as hypertension (aOR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.6), diabetes (aOR 1.8, 95% CI 1.4–2.2), chronic renal disease (aOR 3.7, 95% CI 1.6–10.0), malignancy (aOR 3.7; 95% CI 1.1–7.2), and TB (aOR 2.2; 95% CI 1.1–4.4) were more likely to have died compared with those who did not have existing comorbidities.

There was a lower risk of mortality among HCWs who were mixed race (aOR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–0.8) when compared with black HCWs, admitted in the public sector (aOR 0.7; 95% CI 0.5–0.9), and in pre-wave 1 (aOR 0.6; 95% CI 0.3–0.9) compared with wave 1. There was no statistically significant difference in mortality between wave 1 and wave 2 (aOR 1.1; 95% CI 0.9–1.5).

DISCUSSION

In total, 6364 COVID-19 admissions (2.7% of all hospital admissions) had been reported among HCWs across South Africa, as of April 30, 2021. South Africa experienced its first and second waves a few months later than other countries (Contou et al., 2021; Ioannidis and Contopoulos-Ioannidis, 2021; Salyer et al., 2021). The implementation of the 4-week hard lockdown period in the country following identification of the first case likely slowed transmission of COVID-19 infection in the population (Salyer et al. 2021). Nonetheless, early studies on COVID-19 in other parts of the world, including South Africa, reported that large proportions of early cases were reported among HCWs (Kim et al., 2020; Salyer et al., 2021).

In this study, there was a higher proportion of HCW admissions in wave 1 (48.6%; n = 3095) compared with wave 2 (32%; n = 2036). In pre-wave 1 and wave 1, the spread of the virus was new in the country; facilities and the frontline workers were not prepared to handle the rising COVID-19 cases. Work overload, lack of PPE, and poor infection control, which resulted in outbreaks in hospitals and limited training on handling the new infection, among other factors, were reported risk factors for HCW infections in the first wave (Mhango et al., 2020; Alshamrani, 2021). Improved competency in handling infected patients, as well as better preparedness in facilities, may have resulted in a decrease in HCW admissions (Jassat et al., 2021; Contou et al., 2021). In addition, COVID-19 exposure in the first wave may have increased antibody levels among HCWs, resulting in improved immunity against the infection in the second wave (Nunes et al., 2021; Milazzo et al., 2021).

Our study compared the characteristics of HCWs and non-HCWs. HCWs were less likely to be males, and more likely to be in the 30–59 years age group and to be admitted in the private sector. About 10.8% (n = 687) of admitted HCWs were in the 60–65 years age group. The study found that HCWs were less likely to have mortality as an outcome (aOR 0.6; 95% CI 0.5–0.7) compared with non-HCWs after adjusting for other factors. The improved outcome among HCWs may be explained by factors such as age, with around 61% (n = 3872) of included HCWs in the study found to the middle age group (40–59 years), as well as improved medical care and treatment, most likely accessed through the private sector (63.3%; n = 4030) (aOR 0.7; 95% CI 0.5–0.9). Similar studies comparing COVID-19 infections among HCWs and non-HCWs reported that being an HCW was not associated with increased risk of mortality (Kim et al., 2020; Alshamrani, 2021). Furthermore, the risk of mortality was shown to be higher for older HCWs (≥ 60 years) (Kim et al., 2020).

The multivariate analysis showed that risk of mortality increased with age, with those in the older age group (40–65 years) having a higher risk of mortality compared with the young age group (20–29 years). Older age groups have been shown to be more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and severe outcomes, such as mortality, compared with younger age groups (Wan et al. 2021). Compromised immunity and chronic diseases, often reported in older patients, are some of the factors that increase the risk of mortality among older age groups. The impact of age on mortality among the HCWs in our study was further reinforced by the high case fatality rate observed in older age groups (12.2% and 23.4% among those aged 50–59 and 60–65 years, respectively). Likewise, increased COVID-19 mortality has been reported among older age groups in other studies, especially in those aged ≥ 60 years (Sornette et al., 2020; Rastad et al., 2020).

A systematic review and meta-analysis reporting on characteristics of HCWs with COVID-19 and associated risk factors from several countries, including China, USA, Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and Spain, showed that HCWs had better COVID-19 outcomes when compared with the general population (Gholami et al., 2021). According to the study, COVID-19-related mortality was reported in 1.5% of HCWs. Risk factors associated with COVID-19 mortality in patients were the presence of comorbidities, sex, and age (Gholami et al., 2021).

A study comparing risk factors for HCWs with those of the general population or non-HCWs across different studies found age to be a common predictor of COVID-19 mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (Dalal et al., 2021). For example, a cross-sectional study assessing differences in mortality rates in countries across sub-Saharan Africa found that 51.3% of all reported deaths occurred in the over 60 years age group (Dalal et al., 2021).

Previous studies have shown that males were twice as likely to be at high risk of mortality than females across all age groups (Clark et al., 2020; Undurraga et al., 2021; Becerra-Muñoz et al., 2020; Boulle et al., 2020); however, our study did not find an association between male sex and mortality among HCWs. The presence of comorbidities in our study was identified as a significant factor for HCW admission and in-hospital mortality related to COVID-19 (Zamparini et al., 2020; Jassat et al., 2020; Palaiodimos et al., 2020). For example, HCWs with obesity had a 70% increased risk of hospital admission during the study period. Comorbidities have previously been shown to increase the development of infectious diseases, including COVID-19 (Chutiyami et al., 2022). Furthermore, our results showed that admitted HCWs who had hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal diseases, malignancy, or current or past TB history were more likely to die compared with those without these comorbidities (Barek, 2020; Jassat et al., 2020; Noor and Islam, 2020).

Even though obesity has been shown to increase COVID-19 mortality, as an independent risk factor for comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension (Bello-Chavolla et al. 2020; Chu et al. 2020), our study did not find obesity to be a significant factor in COVID-19-related mortality among HCWs; this was likely due to the underreporting of this variable. In addition, our study found that HIV infection in HCWs was not associated with COVID-19 mortality in admitted HCWs, as reported in the study by Jassat et al. (2020), in which HIV and TB were found to increase the risk of hospital mortality in the general population (Jassat et al., 2020). Drugs used in antiretroviral therapy (ART), such as tenofovir (TDF) and lopinavir-ritonavir, have been found to reduce the risk of severe COVID-19 in people living with HIV (Davies, 2020; Jassat et al., 2020). The lack of association in our study could be the result of HIV-infected HCWs receiving ART.

A study conducted in the Western Cape in South Africa on the risk of HIV for COVID-19 mortality found an overall increased risk among people living with HIV, while those who received TDF as ART treatment had a lower risk of COVID-19 mortality. In a poorly resourced country such as South Africa, TB infection prevention and control (IPC) measures are frequently poorly implemented. Some reports have shown that HCWs who care directly and indirectly for TB patients irregularly use appropriate respiratory protection, resulting in a high prevalence of TB among HCWs (Malotle et al,. 2017). Our study found that a current or past TB history was associated with HCW COVID-19 mortality.

Hospital capacity was assessed in our study using the national weekly number of admissions as a proxy for burden of hospital admission. The risk of in-hospital mortality for HCWs was significantly associated with higher weekly national admissions, indicating that occupational factors, such as overwhelmed hospital admissions, may increase work stress, resulting in higher odds of severe COVID-19 outcomes in HCWs (WHO, 2021; Costantino et al., 2021). Variations in CFR observed among hospitalized HCWs may be the result of differences in COVID-19 infection at a population level, varying prevalence of comorbid diseases, differences in healthcare access and treatment, or the incomplete reporting of deaths within the target population (Jassat et al., 2021b).

Some studies investigating the association of ethnicity with COVID-19-related mortality and have found that HCWs from ethnic minority groups were at increased risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes compared with white HCWs (Phiri et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). Our study showed that HCWs who were of mixed race were less likely to die when compared with admitted black HCWs. In South Africa and in many other countries, HCWs from ethnic minority groups are at an increased risk of COVID-19 infection and adverse outcomes due to many factors, including lifestyle factors and lower socioeconomic status, which may increase disease transmission (Jassat et al., 2021b; Phiti et al., 2021).

HCWs reported as doctors in our study were found to have increased risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality (aOR 3.2; 95% CI 1.4–7.7) compared with other HCW occupational groups. Doctors, like nurses, provide more direct patient care than most other HCWs, which may be the reason for the observed increased risk of COVID-19-related mortality in this group (Spilchuk et al., 2022).

HCWs in the Eastern Cape and Limpopo provinces had increased risk of COVID-19 mortality. While most HCWs would have medical insurance to access private health care, our study showed that COVID-19 mortality was 30% less likely to occur in HCWs admitted in the public sector compared with the private sector. In contrast, other studies have reported admission of non-HCWs to public-sector facilities as being associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 mortality (Phaswana-Mafuya et al., 2021). Mortality differences observed between provinces and sectors may be associated with differences in socioeconomic factors in the populations served by each sector, as well as the quality of care offered in healthcare facilities at the provincial level (Jassat et al., 2021a).

In summary, HCWs in our study had an approximately 60% lower mortality compared with non-HCWs. Older age group, ethnicity, presence of existing comorbidities, and healthcare facilities accessed at provincial and sector levels were risk factors for increased mortality observed in the cohort.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was that it used real-time data from an ongoing hospital surveillance system (DATCOV), covering a large number of public and private health facilities across provinces in South Africa. While the results of this study are not generalizable to the entire HCW population in South Africa, the results provide adequate representativeness of the target population — i.e. hospitalized HCWs in SA. The daily hospital surveillance therefore provides an opportunity for implementing a nationwide registry on COVID-19 admissions and monitoring the impact of targeted interventions, such as vaccinations, on admissions and mortality, and thus supports informed decision-making with regard to public health policy.

As a newly developed surveillance programme, there are some limitations with DATCOV. First, the system has not yet been linked with other data sources, such as laboratory records, mortality records, and other national hospital records, to verify and confirm occupation and comorbid disease status, which may result in under-reporting of such fields. Second, data submitted to DATCOV are dependent on information submitted by healthcare institutions; thus, possible incompleteness of data was a limitation in this study. The risk of heterogeneity of study variables due to data quality was minimized in the study through data quality checks to increase representativeness of the data (Supplementary material).

The proportions of incomplete data for comorbidities that were included in the multivariate model for mortality ranged from 20.7% to 24.9% (Supplementary material). Obesity data were excluded from the final model due to the high proportion of missing data (72.9%).

Another limitation was that information gathered on comorbidities was based on the patient's written or electronic hospital records, and was not verified, because there were no existing information systems that would confirm patient history or existing comorbidities. In addition, clinical measurements of hypertension and diabetes were not reported in this study to validate the patient-reported comorbidities submitted to DATCOV.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of admitted HCWs on the DATCOV surveillance system, and assess factors associated with HCW in-hospital mortality. In wave 1 of the pandemic there was a higher proportion of HCW admissions in South Africa compared with wave 2. Mortality was less likely among HCWs in wave 2, despite the more transmissible and severe beta variant. Better awareness of the disease, improved treatment protocols, and increased antibody levels and subsequent immunity against the infection may have contributed to the decline in HCW admissions and mortality in the second wave. Our results suggest that targeted intervention, such as the vaccination of older age groups and those with comorbidities, has the potential to reduce mortality further.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding source

DATCOV is funded by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) and the South African National Government. No additional funding was obtained towards the completion of this analysis and the development of this manuscript.

Ethical approval statement

The authors confirm that all relevant ethical guidelines were followed, and any necessary institutional research body (IRB) and ethics committee approvals for the study were obtained. The Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand approved the study as part of a national surveillance program (ethics reference no: M160667). All methods were carried out in accordance with the accepted national and international guidelines and standards.

Authors’ contributions

NT performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. NT, WJ, CC, and NN were major contributors in writing the original draft. All authors critically reviewed and contributed scientific inputs equally to drafts of the manuscript. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this current study are available in the repository of the National Institute of Communicable Diseases. The data can be made available on request, which may be directed to waasilaj@nicd.ac.za. Those requesting data will need to sign a data access agreement. The request will require approval by the National Department of Health.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish the acknowledge the DATCOV team at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, the National Department of Health, the nine provincial departments of health, the Hospital Association of Southern Africa (HASA), private hospital groups, and public-sector hospitals who submitted data to DATCOV. The health professionals who have submitted data are acknowledged, and are listed as the DATCOV author group at https://www.nicd.ac.za/diseases-a-z-index/covid-19/surveillance-reports/daily-hospital-surveillance-datcov-report/.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.08.014.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Alshamrani MM, El-Saed A, Al Zunitan M, Almulhem R, Almohrij S. Risk of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality among healthcare workers working in a large tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;109:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basera TJ, Jabulani N, Mark EE. Prevalence and risk factors of latent tuberculosis infection in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra-Muñoz VM, Núñez-Gil IJ, Eid CM, Aguado MG, Romero R, Huang J, et al. Clinical profile and predictors of in-hospital mortality among older patients admitted for COVID-19. Age and Ageing. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielicki JA, Duval X, Gobat N, Goossens H, Koopmans M, Tacconelli E, et al. Monitoring approaches for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulle A, Davies M-A, Hussey H, Ismail M, Morden E, Vundle Z, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19 death in a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles M, Cape Argus news. South African health care workers first up to receive country's initial batch of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/sa-healthcare-workers-first-up-to-receive-countrys-initial-batch-of-covid-19-vaccines-aea5c3c9-18f8-4d0c-bf4a-a338b8ba7d61. 2021 (accessed June 17, 2021).

- Chu Y, Yang J, Shi J, Zhang P, Wang X. Obesity is associated with increased severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Medical Research. 2020;25(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40001-020-00464-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, Guthrie B, Wang HH, Mercer SW, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(8):e1003–e1017. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contou D, Fraissé M, Pajot O, Tirolien J-A, Mentec H, Plantefève G. Comparison between first and second wave among critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to a French ICU: no prognostic improvement during the second wave? Critical Care. 2021;25(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03449-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino C, Emanuele C, Maria GV, Fabio T, Carmelo MM, Guido L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare professionals and general population during ‘first wave’ of COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study conducted in Sicily. Italy. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.644008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal J, Triulzi I, James A, Nguimbis B, Dri GG, Venkatasubramanian A, et al. COVID-19 mortality in women and men in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M-A HIV and risk of COVID-19 death: a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province. South Africa. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.02.20145185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020;8(4):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami M, Fawad I, Shadan S, Rowaiee R, Ghanem H, Khamis AH, Ho SB. COVID-19 and healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;104:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobler L, Mehtar S, Dheda K, Adams S, Babatunde S, Van der Walt M, et al. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in health care workers in South Africa: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassat W, Cohen C, Masha M, Goldstein S, Kufa-Chakezha T, Savulescu D, et al. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in South Africa: the intersection of communicable and non-communicable chronic diseases in a high HIV prevalence setting. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.21.20248409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jassat W, Mudara C, Ozougwu L, Tempia S, Blumberg L, Davies M-A, et al. Increased mortality among individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 during the second wave in South Africa. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.09.21253184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jassat W, Cohen C, Tempia S, Masha M, Susan Goldstein S, Kufa T, Murangandi P, Savulescu D, Walaza S, Bam JL. Risk factors for COVID-19-related in-hospital mortality in a high HIV and tuberculosis prevalence setting in South Africa: a cohort study. The Lancet HIV. 2021;8:e554–e567. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00151-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R, Nachman S, Fernandes R, Meyers K, Taylor M, LeBlanc D, et al. Comparison of COVID-19 infections among healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers. PloS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malotle M, Spiegel J, Yassi A, Ngubeni D, O'Hara L, Adu P, et al. Occupational tuberculosis in South Africa: are health care workers adequately protected? Public Health Action. 2017;7(4):258–267. doi: 10.5588/pha.17.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinda E, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Zungu N, Moyo S, Kondlo L, et al. Towards achieving the 90–90–90 HIV targets: results from the South African 2017 national HIV survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09457-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhango M, Dzobo M, Chitungo I, Dzinamarira T. COVID-19 risk factors among health workers: a rapid review. Safety and Health at. Work. 2020;11(3):262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mike Toole AM US, van Gemert-Doyle Caroline and Majumdar S. COVID-19 global trends and analyses volume 1: global epidemiology and trends. https://burnet.edu.au/system/asset/file/4478/1.1.1_January_Global_Update_Vol_1_COVID-19_Epidemiology_and_trends_sml.pdf (accessed June 17, 2021).

- Milazzo L, Lai A, Pezzati L, Oreni L, Bergna A, Conti F, Meroni C, Minisci D, Galli M, Mario C. Dynamics of the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among healthcare workers at a COVID-19 referral hospital in Milan. Italy. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2021;78:541–547. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-107060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute For Communicable Diseases, Media Brief. Latest confirmed cases of COVID-19 in South Africa (31 Dec 2020). https://sacoronavirus.co.za/category/press-releases-and-notices/ [press release] (accessed June 17, 2021).

- National Institute For Communicable Diseases, Centre for Respiratory Diseases and Meningitis and Outbreak Response Unit. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Guidelines for case finding, diagnosis and public health response in South Africa. Version 3. Updated 25-06-2022. https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NICD_DoH-COVID-19-Guidelines_Final_3-Jul-2020.pdf (accessed August 24, 2022).

- Noor FM, Islam MM. Prevalence and associated risk factors of mortality among COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Journal of Community Health. 2020;45(6):1270–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00920-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes MC, Baillie VL, Kwatra G, Bhikha S, Verwey C, Menezes C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers in South Africa: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palaiodimos L, Kokkinidis DG, Li W, Karamanis D, Ognibene J, Arora S, et al. Severe obesity, increasing age and male sex are independently associated with worse in-hospital outcomes, and higher in-hospital mortality, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker A, Koegelenberg CF, Moolla MS, Louw EH, Mowlana A, Nortjé A, et al. High HIV prevalence in an early cohort of hospital admissions with COVID-19 in Cape Town. South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 2020;110(9):982–987. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i10.15067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phaswana-Mafuya N, Shisana O, Jassat W, Baral SD, Makofane K, Phalane E, Zuma K, Zungu N, Chadyiwa M. Understanding the differential impacts of COVID-19 among hospitalised patients in South Africa for equitable response. South African Medical Journal. 2021;7(2):e22581. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i11.15812. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-m_samj_v111_n11_a20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastad H, Karim H, Ejtahed HS, Tajbakhsh R, Noorisepehr M, Babaei M, Azimzadeh M, et al. Risk and predictors of in-hospital mortality from COVID-19 in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetology and Metabolic Syndrome. 2020;12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13098-020-00565-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees K, Dunlop J, Patel-Abrahams S, Struthers H, McIntyre J. Primary healthcare workers at risk during COVID-19: an analysis of infections in HIV service providers in five districts of South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 2021 doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i4.15434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyer SJ, Maeda J, Sembuche S, Kebede Y, Tshangela A, Moussif M, et al. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AS, Wood R, Gribben C, Caldwell D, Bishop J, Weir A, et al. Risk of hospital admission with coronavirus disease 2019 in healthcare workers and their households: nationwide linkage cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sornette D, Mearns E, Schatz M, Wu K, Darcet D. Interpreting, analysing and modelling COVID-19 mortality data. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2020;101(3):1751–1776. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05966-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilchuk V, Arrandale VH, Armstrong J. Potential risk factors associated with COVID-19 in health care workers. Occupational Medicine. 2022;72:35–42. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqab148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga EA, Chowell G, Mizumoto K. COVID-19 case fatality risk by age and gender in a high testing setting in Latin America: Chile, March–August 2020. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2021;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00785-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Global research collaboration for infectious disease preparedness. COVID 19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). In Global research and innovation forum: towards a research roadmap. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum 2020a (accessed June 17, 2021).

- World Health Organization, Scientific brief. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions 2020b (accessed June 17, 2021).

- World Health Organization, Technical document. The impact of COVID-19 on health and care workers: a closer look at deaths. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345300 2021 (accessed June 17, 2021).

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-J, Dong X, Liu G-H, Gao Y-d. Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12016-022-08921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamparini J, Venturas J, Shaddock E, Edgar J, Naidoo V, Mahomed A, et al. Clinical characteristics of the first 100 COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. Wits Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;2(2):105–114. doi: 10.18772/26180197.2020. v2n2a1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this current study are available in the repository of the National Institute of Communicable Diseases. The data can be made available on request, which may be directed to waasilaj@nicd.ac.za. Those requesting data will need to sign a data access agreement. The request will require approval by the National Department of Health.