Abstract

Pro-apoptotic BAK and BAX are activated by BH3-only proteins to permeabilise the outer mitochondrial membrane. The antibody 7D10 also activates BAK on mitochondria and its epitope has previously been mapped to BAK residues in the loop connecting helices α1 and α2 of BAK. A crystal structure of the complex between the Fv fragment of 7D10 and the BAK mutant L100A suggests a possible mechanism of activation involving the α1-α2 loop residue M60. M60 mutants of BAK have reduced stability and elevated sensitivity to activation by BID, illustrating that M60, through its contacts with residues in helices α1, α5 and α6, is a linchpin stabilising the inert, monomeric structure of BAK. Our data demonstrate that BAK’s α1-α2 loop is not a passive covalent connector between secondary structure elements, but a direct restraint on BAK’s activation.

Subject terms: Cell biology, X-ray crystallography, Protein folding

Introduction

The intrinsic (or mitochondrial) pathway of apoptotic cell death is regulated by the BCL2 protein family [1]. The family consists of three subfamilies: five pro-survival proteins (e.g. BCL2, MCL1), eight pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (e.g. BIM and BID), and two pro-apoptotic pore-forming members (BAK and BAX). Apoptotic signalling initiates a cascade of protein-protein interactions between pro-survival and pro-apoptotic family members, resulting in mitochondrial pore formation, caspase activation and cell death. BAK and BAX are the essential mediators of apoptotic cell death via the intrinsic pathway [2]. Despite displaying sequence and structural similarity to pro-survival members of the BCL2 family, they function in opposition to them. A key distinguishing feature is that BAK and BAX are metastable proteins [3, 4]. Their encounters with pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins are transient and result in their conformational rearrangement [5–8] and the permeabilisation of the mitochondrial outer membrane. In contrast, complexes formed between pro-survival BCL2 family members and BH3-only proteins are high affinity and hence long-lived [9]. Those complexes prevent the pro-survival protein from binding to and restraining BAK/BAX and, in addition, sequester and restrain BH3-only proteins from directly activating BAK/BAX [10].

Recently we reported that antibodies to BAK or BAX may substitute for BH3-only proteins as triggers of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation [11]. 7D10 is a rat monoclonal antibody (previously designated AG2) raised against human BAKΔC25 [7]. Its binding site on non-activated BAK includes residues G51-D57, located in the connecting segment between its first and second α-helices (the α1-α2 loop), and both the antibody and its Fab fragment permeabilised mitochondria from cells expressing human BAK. Those studies [11] also explored the mechanism of BAK activation by 7D10 binding. Moving the epitope to different locations within the loop showed that 7D10 activates BAK only when its target site is located in the N-terminal part of the loop, i.e. close to the C-terminus of α1. On introducing the FLAG epitope into various locations in the α1-α2 loop, the anti-FLAG antibody had similar BAK-activating properties to 7D10. Disulfide tethers that block BAK activation by the BH3-only protein cBID also prevent antibody-induced activation, suggesting that this antibody and BH3-only proteins trigger similar unfolding events in BAK, namely α1 dissocation and separation of core (α2-α5) and latch (α6-α8) domains, followed by dimerisation of the core domains. 7D10 binding to the α1-α2 loop was suggested to disturb α1 rather than α2, as a disulfide tether between α1 and the α1-α2 loop (H43C-M60C) failed to block antibody-induced activation. A computational model of the complex between 7D10 and BAK also showed a cavity forming beneath α1, suggesting an effect of 7D10 binding on α1 itself and a possible rationale for the requirement that the epitope be sequentially adjacent to α1 [11].

The anti-BAX antibody 3C10 exhibits remarkably similar properties on mitochondrial BAX. The epitope for 3C10 is immediately C-terminal to BAX helix α1 and it activates a mitochondrial mutant form (S184L) of BAX [11]. Although 3C10 activates mitochondrial BAX it actually inhibits cytosolic BAX where helix α9 is folded into a groove formed by helices α3α4α5 on the surface of the protein [12]. A crystal structure of the 3C10 Fab’ bound to the BAX mutant P168G illustrates that 3C10 does indeed unfold the C-terminal end of helix α1 of BAX [13], disturbing contacts between the BH4 motif [14] and the rest of the protein. Thus, these findings on 3C10 activation of mitochondrial BAX supported the interpretation of 7D10’s proposed mechanism of action on BAK.

To better understand the mechanism of activation of BAK by antibody 7D10, we have now determined a crystal structure of the Fv fragment of 7D10 bound to human BAK. The BAK construct is based on that commonly used to study inactive BAK [15], i.e. with its membrane anchor (α9) and its N-terminal extension removed. Crystals of the complex have only been obtained by further introducing the substitution L100A [16] that is known to elevate the threshold for activation of BAK by BH3-only proteins on liposomes. The experimental structure is unlike the previously described computational model [11] and suggests an unexpected role for the α1-α2 loop (especially M60) in stabilising BAK. Experiments with BAK mutants confirm that residue M60 stabilises the monomeric, inactive fold of BAK, and that 7D10 activates BAK by disrupting M60’s linchpin role.

Results

Crystallisation and the mutant BAKL100A

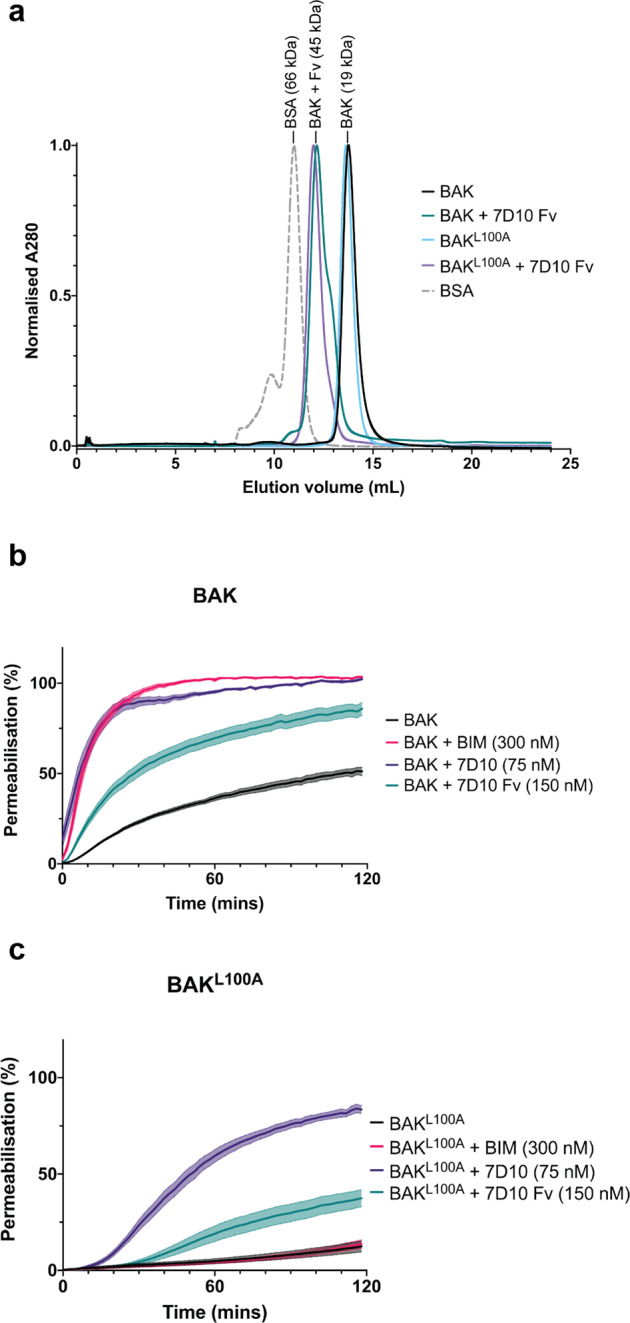

Complexes of the 7D10 Fv fragment bound to BAKΔN22ΔC25Δcys (hereafter referred to as BAK) or to BAKΔN22ΔC25ΔcysL100A (hereafter, BAKL100A) are monodisperse by size exclusion chromatography with an apparent molecular weight of ca 45 kDa (Fig. 1a). Attempts to crystallise complexes of 7D10 with BAK have so far proven successful only by using the mutant L100A. In the presence of the crystallisation medium, 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), high molecular weight species appear in the wild-type complex, but not in the mutant complex, potentially frustrating crystallisation (Fig. S1a). The L100A mutant was designed to monitor the role of L100 in engaging an activating BH3 peptide within BAK’s α3α4α5 (groove) receptor site and shown to have reduced responsiveness to a BH3 peptide [16].

Fig. 1. Characterisation of the complex between antibody 7D10 and both BAK and BAKL100A.

a Size exclusion chromatography demonstrates that the 7D10 Fv fragment forms a 1:1 complex with wild-type BAK and with BAKL100A variant. (BAK is ΔN22ΔC25Δcys 6X His, i.e. with N- and C-terminal truncations, with wild-type cysteine residues replaced with serine and a C-terminal His-tag). BSA, bovine serum albumin, MW 66 kDa. b, c Both the 7D10 antibody and its Fv fragment can permeabilise liposomes to which BAK or BAK L100A has been immobilised via a C-terminal His-tag. Results show the mean (line) ± SEM (shaded area) for three independent experiments with at least two technical replicates. BAK is used at 150 nM. Controls shown for activation by BIM BH3 peptide reproduce previous results [16].

Thermal shift analysis shows that the melting temperature of the mutant is 12 °C higher than wild-type (Fig. S1b). Thus, our original design of this mutant, to abrogate interactions between L100 and the so called ‘h0’ residues of an activating BH3 motif [16], has had the unintended consequence of stabilising BAK itself, in addition to potentially reducing binding by BH3-only proteins. To determine whether BAKL100A could still be activated by 7D10 we performed liposome release assays, measuring the release of fluorescent dye from liposomes containing a nickel-charged lipid head group [17] to which BAK is attached via a C-terminal His tag. Both the 7D10 antibody and its Fv fragment released dye from liposomes containing wild-type BAK and BAKL100A, the latter with significantly delayed kinetics compared to wild-type BAK (Fig. 1b, c). Thus, BAKL100A is compromised in its capacity to transition to a membrane-permeabilising conformation when provoked either by the BH3-only protein BIM [16] or by the antibody 7D10.

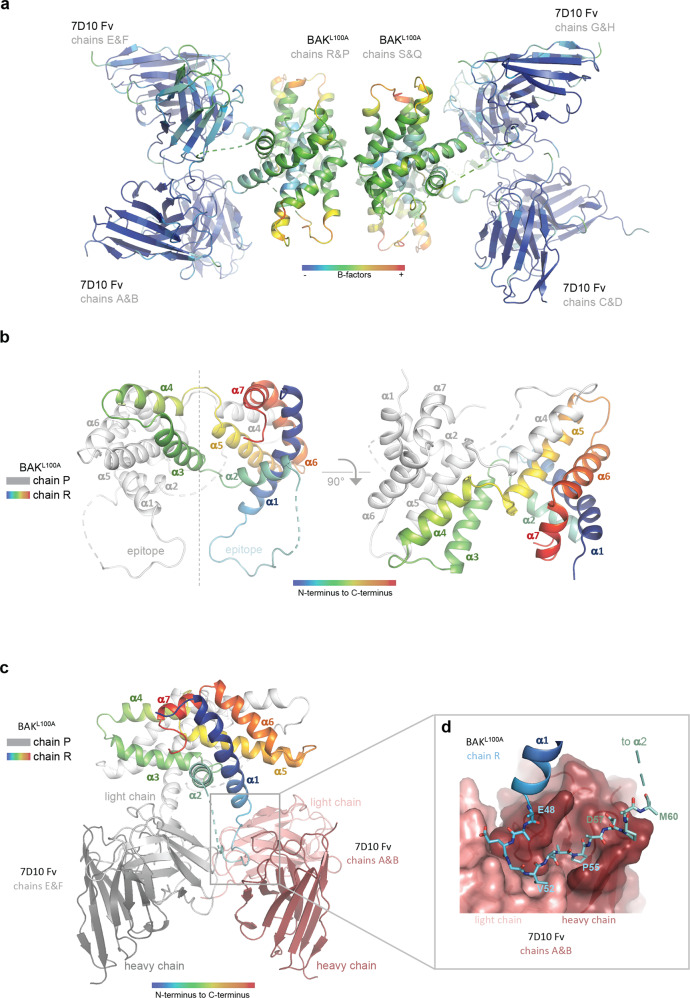

Structural characterisation of 7D10 Fv binding to BAKL100A

The asymmetric unit of the crystal contains four 7D10 Fv fragments associated with four BAKL100A polypeptides (chains P, Q, R and S) arranged as two α3α4 domain-swapped dimers (Fig. 2a). The α3α4 domain-swapped BAKL100A dimer is reminiscent of a crystal structure of BCL-W [18]. It arises as a consequence of crystallisation of the complex with 7D10, as the complex was monomeric by size exclusion chromatography at the point of initiating the crystallisation trials (Fig. 1a). Because 7D10 Fv can activate BAKL100A on liposomes it is not unexpected that the crystallisation drop may contain some partially unfolded BAKL100A bound to 7D10 Fv. Whilst the crystallisation conditions have favoured the observed domain-swapped dimer, we envisage that this is but one of a number of partially unfolded conformers induced by 7D10-binding.

Fig. 2. Structure of the complex between antibody 7D10 and BAKL100A.

a The BAKL100A moieties of the complex have elevated B-factors. The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains four BAK polypeptides (central) with four attached Fv fragments. Colouring is by B factor (low-blue, high-red) indicating that the BAK parts of the image are more disordered. b In the crystal, BAKL100A is an α3α4 domain-swapped dimer. Chain R of the BAK dimer is coloured rainbow (blue - α1 through red - α7), and chain P in white. In the left panel the pseudo dyad symmetry axis is vertical. The cross-over connections between α4 and α5 are at the top of the figure. The cross-over connections between α2 and α3 are in the centre of the figure where the symmetry breaks down. This connection is built for the chain R (cyan - α2 to green - α3), but no interpretable electron density is observed for α3 on the chain P (white dashed lines). The epitope segments are at the bottom of the figure, the dashed lines indicating disorder in those parts of the α1-α2 loop C-terminal to the epitope. In the right panel the view is down the pseudo dyad symmetry axis. The cross-over connections between α4 and α5 are in the foreground near the symmetry axis. c The α3α4 domain-swapped BAKL100A dimer binds two copies of the 7D10 Fv fragment. The BAKL100A moieties occlude each other in this view. Chain R of the BAK dimer (coloured rainbow) engages Light chain Variable domain (light pink) and Heavy chain Variable domain (dark pink) in the foreground, with chain R (white) to Light chain Variable domain (light grey) and Heavy chain Variable domain (dark grey) at the rear. The crystal asymmetric unit contains two essentially identical copies of this dimer. d The BAK epitope snakes its way across a binding crevice in the 7D10 Fv (pink surface). BAK residues shown as sticks are 48EAEGVAAPADPEM60 with contacting residues in bold in the sequence. Side chains of E48, E59 and M60 are disordered and shown as alanine.

Electron density for the BAKL100A moieties is generally poor (Fig. 2a), consistent with the observation that the structure solution by molecular replacement could only be initiated by a model for the Fv. Two regions in BAKL100A could not be interpreted based on the electron density maps. The first was a section (up to 7 residues) of the α1-α2 loop following the epitope in all four BAKL100A polypeptides, possibly due to antibody binding to the first half of the loop. The second uninterpretable region was helix α3 of chains P and Q, with this disordered segment related to the presence of the domain-swapped dimer of BAKL100A in the crystal. Helices α3 and α4 are swapped between chains P and R and between chains Q and S. The trace of chains R and S through α3 precludes an identical structure for their partner chains in the domain-swapped dimers, which may be the underlying cause of the disorder in α3 of chains P and Q (Figs. 2b, c, S2).

The BAKL100A:Fv interface is well defined in the structure (Fig. 2d) and is consistent with earlier characterisation of the 7D10 epitope as comprising the 51GVAAP55 residues [11]. It displays hydrogen bonds with the BAKL100A backbone (E50 carbonyl to light chain H91 side chain; V52 amide to light chain H91 backbone; V52 carbonyl to heavy chain S104 side chain; A54 amide to heavy chain K102 backbone) and with the side chain of D57 (to heavy chain backbone amides of A54 and I56, and to the side chain of heavy chain S52). BAKL100A V52 and P55 are accommodated in hydrophobic pockets formed predominantly by light chain CDR3 and heavy chain CDR2, respectively. A53 and A56 face the solvent, but all other residues in the segment 51–57 make interactions with 7D10. No other segments of BAKL100A contact the antibody. Previous characterisation of the epitope by site-directed mutagenesis showed that while mutation of E50, V52, A53 and A54 to cysteine retained binding, G51C and P55C mutations inhibited 7D10 binding to BAK [11]. BAK E50C may retain binding through its backbone carbonyl, V52C can still occupy the hydrophobic pocket and retain binding, A53C causes no steric hindrance and retains binding and A54C retains binding through its backbone amide. The larger side chain introduced upon mutation of G51 to cysteine may cause steric hindrance to prevent binding, and mutation of P55 to cysteine, while still occupying a hydrophobic pocket, may alter secondary conformation and thus backbone interactions.

The structure also provides insight into the complex effects of D57 mutation previously observed [11]. While the D57N mutation prevented binding of 7D10 to inactive human BAK, it was able to bind BAK after activation (e.g. by cBID). In the D57N substitution only one of the two carboxylate interactions with the Fv heavy chain amides can be sustained, potentially enabling binding but only after conformational changes associated with activation have occurred. Further, the D57C mutant is activatable by 7D10, after which the introduced C57 side chain can form a disulfide bond with a partner C57. D57 is accessible at the edge of the epitope, from where the C57 crosslink is readily conceivable.

The shape complementarity metric Sc [19] is 0.804 (over the trimmed surface area of 360 Å2) and the buried surface area is 540 Å2 on each molecule. These metrics, in particular the small buried surface area, are more reminiscent of antibody-peptide complexes than antibody-protein complexes [20], consistent with 7D10 recognising a linear epitope [11, 21]. The previously reported computational model for BAK bound to 7D10 [11] incorrectly placed the BAK epitope clasped between CDR2 and CDR3 loops of the heavy chain, whereas the x-ray crystal structure shows it nestled between CDR3 loops of both the heavy and light chains. The buried surface area in the model was more similar to an antibody:protein complex (1411 Å2), as the protein docking approach used to generate the model selects for complexes with a large number of favourable interactions at the interface.

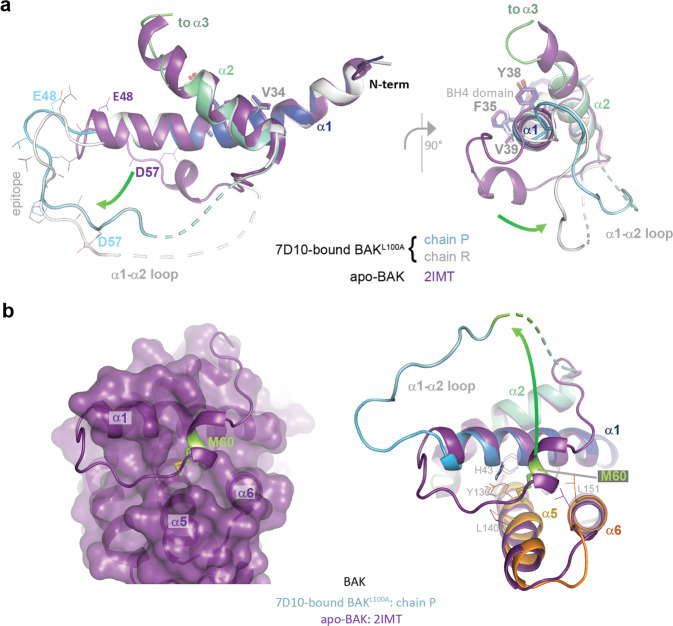

The four copies of BAKL100A within the asymmetric unit are comparable through their α1 helices, most notably in their BH4 motifs [14] where V34, F35, Y38 and V39 make interactions with α2, α5, α6 and α8 in an identical manner to that observed in inactive, monomeric BAK [15, 21] and in BAKL100A [16] (Fig. 3a). This observation is not consistent with a mechanism by which 7D10 activates BAK through destabilising the BH4 residues in α1, as observed with antibody 3C10 and BAX [13]. However, a potentially destabilising consequence of the engagement of BAK with 7D10 is the removal of M60 (in the α1-α2 loop) from a binding-pocket formed by residues in α1 (V39, H43), α5 (Y136, A139, L140) and α6 (L151) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Differences between apo- and 7D10-bound structures of BAK.

a Orthogonal views of the overlay of apo-BAK (2IMT - purple) on chains R (blue to cyan) and P (white) of the antibody-bound-BAKL100A, showing only helices α1 and α2. The views focus on the C-terminus of helix α1 and the movement of the α1-α2 loop comparing the structures (green arrow). The epitopes are lower right, involving amino acids from the single helical turn in the α1-α2 loop of the apo-BAK structure. Epitope residues are shown as lines, BH4 residues as sticks 34VFRSYV39. The antibody does not disturb the structure of α1, only of the α1-α2 loop. The C-terminus of α2 is where chain P becomes disordered and where chain R begins to be re-organised for the crossover connection to α3. Two different conformations are observed in the residues connecting the end of α1 to the epitope, 47QEAE50 indicative of the extraction of the loop from the helical fold by the 7D10 Fv engaging the epitope residues 51–57. b M60 is extracted from its conserved binding site in apo-BAK in the crystal structure of the complex with 7D10. The left panel shows a surface representation of the helical bundle of apo-BAK (2IMT - purple) illustrating how the α1-α2 loop (cartoon representation) engages at the surface of the protein, in particular via residue M60 (green) in the single helical turn. The right panel displays an overlay of helices 1, 5 and 6 of apo-BAK (2IMT - purple) and chain P of antibody-bound-BAK (blue to orange), showing M60 (green) in a pocket defined by helices 1, 5 and 6 in apo-BAK and dislodged from that pocket in the 7D10 complex (arrow). The receptor site for M60 is not significantly disturbed by M60’s removal in the 7D10 complex (residues shown as sticks). M60 is not ordered in any of the four BAK polypeptides in the crystal structure of the complex.

In summary, the crystal structure provides an atomic resolution description of the 7D10 epitope (Figs. 2d, S3), that is consistent with previous findings. Binding is associated, not with changes in the BH4 domain (that connects α1 with α2, α5, α6 and α8), but with displacement of the M60 residue from a pocket formed by residues from α1, α5 and α6. The structure is of an α3α4 domain-swapped BAK dimer that probably reflects the ability of 7D10 to induce conformational change in BAK, but the formation of dimers is likely a consequence of the crystallisation conditions and has no known physiological relevance.

7D10 epitope structure in inactive BAK

Four structures of inactive, monomeric human BAK have been reported [15, 22] (PDB codes 2IMS, 2IMT, 2JCN, 2YV6 [23]) and all display stabilising contacts (P55, D57, E59, M60) involving elements of the 7D10 epitope or residues immediately C-terminal to it, summarised in Table 1. The most intimate of these is M60, noted above to be displaced in the 7D10 structure. In addition, contacts between (i) side chains of P55 and L140 (α5), (ii) the side chain of D57 and the ring of Y143 (α5) and (iii) the side chain of E59 and the backbone amides of G149 and F150 (α6), all provide extra contact points for the epitope to the helical framework of BAK. As none of these interactions are observed in the crystal structure of the complex described here, 7D10 binding has disturbed these various stabilising interactions between the α1-α2 loop and the BAK helical bundle.

Table 1.

Crystal structures of BAK: observations on the 7D10 epitope and residue M60.

| -----------------Contacts----------------- | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB | Space group | Unit cell edge (Å) | Resoln (Å) | N | M/D | ligand | (i) P55 | (ii) D57 | (iii) E59 | (iv) M60 | ||

| 2IMS | C2 | 57.5 | 53.7 | 58.3 | 1.48 | 1 | M | apo | + | + | + | + |

| 2IMT | C2 | 57.3 | 53.6 | 58.1 | 1.49 | 1 | M | apo | + | + | + | + |

| 2JCN | P6522 | 62.8 | 62.8 | 138.1 | 1.8 | 1 | M | apo | + | + | + | + |

| 2YV6 | P6522 | 61.8 | 61.9 | 137.5 | 2.5 | 1 | M | apo | + | + | + | + |

| 4U2U | C2 | 110.6 | 39.5 | 88.1 | 2.9 | 2 | D | apo | − | − | − | − |

| 5VWV | P4132 | 139.4 | 1.9 | 1 | D | BIMa | + | + | + | + | ||

| 5VWW | P43212 | 87.8 | 87.8 | 95.5 | 2.8 | 2 | D | BIMa | − | − | − | − |

| 5VWX | P212121 | 61.6 | 76.5 | 77.5 | 2.5 | 2 | D | BIMb | − | − | − | − |

| 5VWY | C2 | 65.9 | 37.5 | 69.6 | 1.56 | 1 | D | BIMc | − | + | + | + |

| 5VWZ | P21 | 38.2 | 56.7 | 79.3 | 1.62 | 2 | M | BIMd | − | + | + | + |

| 5VX0 | P212121 | 48.1 | 63.2 | 121.0 | 1.6 | 2 | M | BIMe | − | + | + | + |

| 5VX1 (hsBAK L100A) | P21 | 41.5 | 39.5 | 108.1 | 1.22 | 2 | M | apo | − | − | − | + |

| 6MCY (mmBAK) | P1 | 37.0 | 59.3 | 79.2 | 1.75 | 4 | M | apo | + | + | + | + |

N: number of BAK molecules in the asymmetric unit.

M/D: monomer/dimer; all dimers here are core/latch dimers resulting from pre-treatment of BAK with CHAPS and BID BH3

BIM: five different BH3 ligands, see details in Brouwer et al. [16].

Contacts: (i) P55-L140 (ii) D57-Y143 (iii) E59-backbone NH of 149 and 150 (iv) M60 in pocket formed from residues in α1, α5 and α6.

In some cases (4U2U, 5VWW, 5VWX, 5VWY), absence of an interaction (−) is due to epitope disorder in that crystal structure.

In an NMR structure of BAK bound to a stapled peptide (PDB code 2MB5) the loop between helices 1 and 2 (including M60) is disordered.

Several conformational changes accompany the L100A mutation [16]. Helix α3 is extended by two residues (H99 and A100) and the helix is shifted towards its N-terminus by ~1.5 Å, the α3-α4 loop is altered, helix α4 starts at residue A107 (not A104 as for wild-type), the α2-α3 connection is less helical and the C-terminus of helix α1 and the 7D10 epitope is altered.

We next examined the α1-α2 loop structure in nine additional crystal structures of BAK (Table 1), some with bound ligands (BIM BH3 peptides), some core/latch dimers (designated D), and one for murine BAK (6MCY). They illustrate that the α1-α2 loop in monomeric BAK and in some core/latch dimer structures has a preferred conformation independent of the crystallisation conditions, crystal environment or the presence of a BH3 ligand in the α3α4α5 binding groove. In this preferred conformation the 7D10 epitope is cryptic, suggesting that 7D10 binding relates to the presence of a more open structure for the α1-α2 loop within the ensemble of conformations in solution, or that 7D10 induces conformational change. Note that while BAKL100A (5VX1) displays some differences to wild-type BAK (e.g. 2IMS) in the vicinity of the epitope (i.e. P55, D57, E59), it retains M60 in its binding pocket (Table 1).

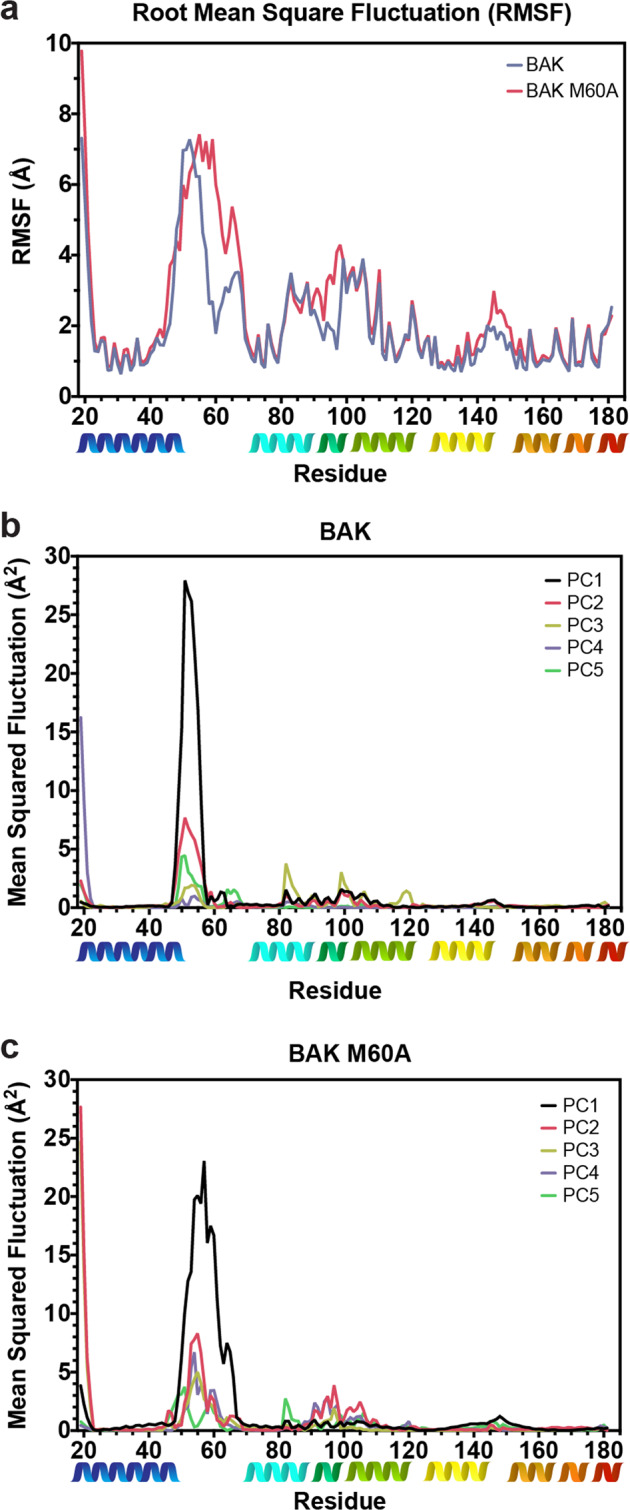

Molecular dynamics

Our previous simulations of wild-type apo-BAK [11] echo the flexibility observed in crystal structures, specifically in the α1-α2 loop residues Q47-P58 (Table 1) and in the α3 (residues N86-H99). Here we have extended those simulations over ten independent replicates each simulated for 2 μs (Fig. 4a). M60 remains in its binding pocket for >98% of the collective simulations, but the secondary structure of the helix α1a, P58-T62, fluctuates significantly. These calculations suggest that the epitope conformation observed in the 7D10 complex could be selected from an ensemble. The correlated movement of the α1-α2 loop with that of α3 (Fig. 4b) is unexpected because these polypeptide segments are not in direct contact with each other.

Fig. 4. Molecular dynamics.

a Root mean square fluctuations of BAK (blue) and BAK M60A (red) each determined from ten independent replicates run for 2 μs. b Principal component analysis of BAK molecular dynamics, showing the top five components. c Principal component analysis of BAK M60A molecular dynamics, showing the top five components.

Molecular modelling of the complex showed that the antibody:epitope structure observed here in the crystal can form without disengaging M60 from its binding pocket. This is achievable because 7D10 makes no interactions with BAK other than through the epitope residues 51–57, and the epitope residues themselves are also dissociated from the BAK helical fold. During four, independent, 1 μs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of a complex so constructed, M60 remained buried in its original location. These results leave open the question as to whether 7D10-binding precedes or follows the ejection of M60 from its binding pocket. In either event, M60 is (eventually) released. A disulfide tether between H43C and M60C does not prevent activation by 7D10 [11]. Whilst this tether links the loop to α1, it compromises the deeper contacts between M60 and α5/α6 (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the critical role for M60 in restraining BAK activation is the stability it provides to α1’s contacts with both the core and latch domains.

BAK M60 mutants are less stable and more sensitive to activation

The structural study implicates M60 as a brake on BAK activation. However, because the structure has relied on the use of the anomalous mutant L100A and a crystallisation medium (MPD) that is itself destabilising of the wild-type BAK structure (Fig. S1), we turned to studies (i.e. M60 mutagenesis) that are uncontaminated by these qualifiers.

Ten independent 2 μs MD simulations of apo-BAK M60A show elevated root mean square fluctuations compared to wild-type in the segments adjacent to and inclusive of residue 60 (Fig. 4a). This enhanced flexibility in the M60A mutant extends to α3 (residues 91–98) and to the α5-α6 corner (residues 145–149). In both wild-type and the M60A mutant, fluctuations in the α1-α2 loop and in α3 are correlated (Fig. 4b, c). Loss of the deep contacts between M60 and residues in α5 and α6 in the M60A mutant are the likely source of the effects seen in the α5-α6 corner, but the altered dynamic properties in α3, and their correlation with α1-α2 loop fluctuations, were unanticipated because the intervening helix, α1, is unaffected by dissociation of M60 from its pocket. This may be yet a further example of altered protein dynamics at sites remote from protein-protein interfaces [24], with the interface affected here being the cis-contact between M60 and its binding pocket.

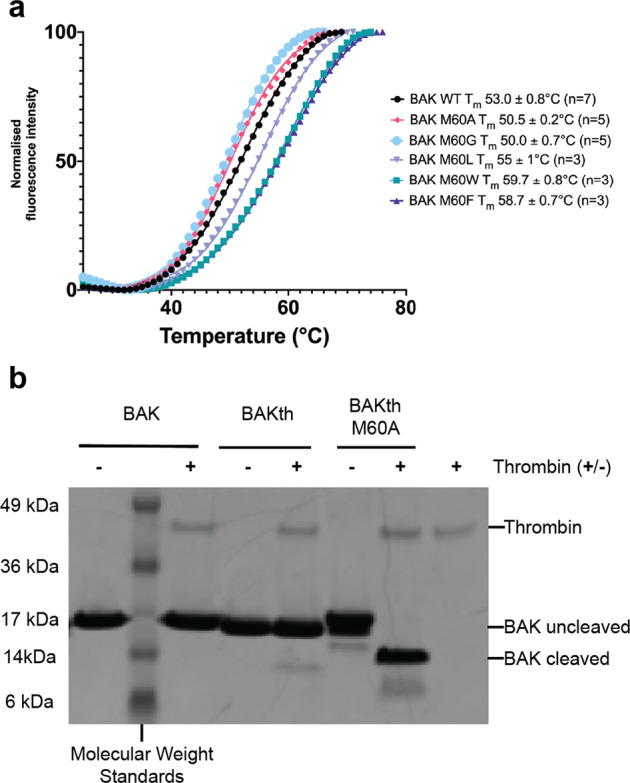

To ascertain any role of M60 in restraining physiological activation of BAK we generated a number of recombinant BAK proteins containing point-mutations at M60. Thermal shift analysis suggests a small reduction in bulk stability for M60A and M60G, no change for M60L, and an increase in stability for M60F and M60W (Fig. 5a). Predictions of the change in folding free energy [25] for M60A and M60G are +2.9 and +3.3 kcal mol−1, respectively, although such estimates are unable to account for the likely increase in entropy accompanying the release of the α1-α2 loop from a restrained conformation.

Fig. 5. Stability and activity profiles of ΒΑΚΔΝ22ΔC25Δcys and M60 mutants.

a Melting temperatures for BAK WT and M60 mutants. The M60G and M60A mutants have reproducibly reduced thermal stability. M60F and M60W have increased thermal stability, while M60L shows similar thermal stability to wild-type. The graph shown is of a single, representative experiment with two technical replicates. Melting temperatures are mean ± SEM from multiple independent experiments as indicated in figure. b The mobility of the α1-α2 loop is enhanced in the M60A mutant, as determined by accessibility to thrombin cleavage. Previously we reported that BAKth was susceptible to thrombin cleavage only after activation [26], in that case by the detergent C12E8.

Accessibility of M60 was studied using a construct (BAKth) containing a thrombin cleavage site immediately C-terminal to M60 in the α1-α2 loop [26]. This construct has BAK residues V61 through Q66 replaced with the sequence -LVPRGS-. We have previously shown that cleavage with thrombin, between R64 and G65, was only possible after the protein had been activated to form dimers by the detergent C12E8 [26]. When the thrombin site is introduced into BAK M60A, cleavage occurred without prior activation (Fig. 5b). Thus, M60 confers a protected conformation on residues 61–66 and mutation to A60 releases this restraint on that portion of the α1-α2 loop.

In liposome release assays (Fig. S4), M60G showed significantly elevated constitutive activity over wild-type and enhanced responsiveness to BID BH3 peptide, while the activity of M60A was more similar to wild-type BAK, with only marginally higher constitutive activity and marginally faster kinetics (Fig. S4a). In contrast, mutation of methionine to the bulky, aromatic residues tryptophan or phenylalanine resulted in significantly lower constitutive activity, and reduced response to BID BH3 stimulus (Fig. S4b). Mutation to leucine resulted in activity that resembles wild-type, however with slower activation kinetics in response to BID BH3.

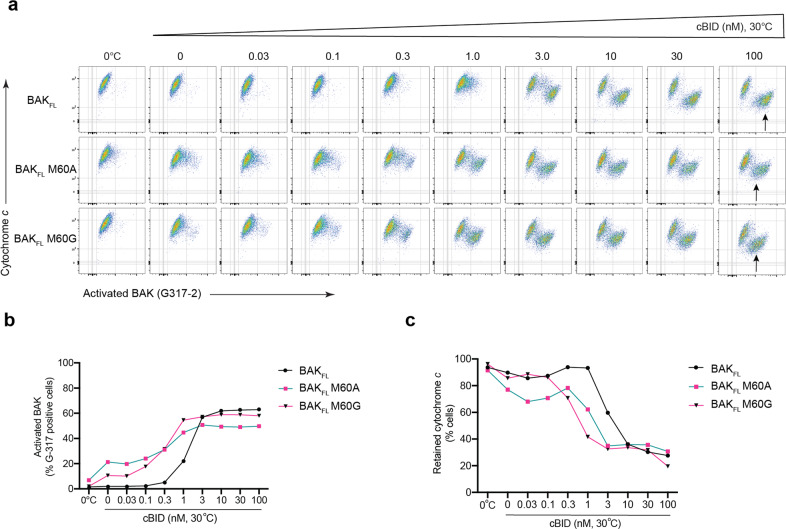

While we had expected both M60A and M60G to show increased activity, only M60G showed a clear increase. We noted that liposome release assays rely on a C-terminal histidine tag in place of the transmembrane domain (α9) to recruit BAK to the liposomes, and the wild-type shows significantly higher constitutive activity than in the cellular context. As such, we turned to a more biologically relevant assay to investigate the M60A and M60G mutants further.

The BAK M60 mutants (M60A and M60G) were next studied for their capacity to respond to cBID when full-length wild-type or mutant BAK was expressed in Bak−/−Bax−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Cells were permeabilied and incubated with cBID to activate BAK, then co-stained with antibodies to activated BAK and cytochrome c and analysed by flow cytometry. As expected, as cBID concentration increased, more cells exhibited activated BAK and released mitochondrial cytochrome c (Fig. 6a). Notably, cells expressing either M60 mutant were more sensitive than BAKΔcys to cBID, evident as higher percentage cells with activated BAK at 0.1–1.0 nM cBID (Fig. 6b). Cells expressing either M60 mutant also released cytochrome c at lower cBID concentrations, as shown by flow cytometry (Fig. 6c) and western blot (Fig. S5a). M60 mutants were also more sensitive to activation by heat, as 10–20% of cells expressing M60 mutants contained activated BAK following incubation at 30 °C in the absence of cBID (Fig. 6b). This propensity of the BAK M60 mutants to activation may have caused high-expressing cells to die during routine culture, as M60A and M60G expression levels were significantly lower than wild-type levels (Fig. S5b), evident also as lower total BAK activation at high cBID concentrations (see arrows, Fig. 6a). Despite the lower levels of the M60 mutants, activation and cytochrome c release occurred more readily, confirming that M60 mutation sensitised BAK to activation.

Fig. 6. M60 mutants are less stable on mitochondria and more sensitive to activation.

Bax−/−Bak−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) expressing full-length BAK (Δcys) or the BAK M60A or M60G mutants were permeabilied and then incubated for 30 min at 0 °C or at 30 °C with the indicated concentrations of cBID. Cells were then stained for activated BAK (G317–2) and cytochrome c and analysed by flow cytometry. Experiment uses cells that were passaged twice following thawing, and is representative of three independent experiments. a Dot blots show populations of cells with activated BAK (x-axis) and decreased mitochondrial cytochrome c (y-axis). Note that BAK M60 mutant cells respond to lower cBID concentrations (0.3–1.0 nM) despite evidence of less BAK in each cell (arrows). b Activation of BAK as measured by % cells. Cells with increased G317–2 staining from (a) were gated and calculated as % total cells. c Cytochrome c release from cells as measured by % cells. Cells with decreased cytochrome c staining from (a) were gated and calculated as % total cells.

Discussion

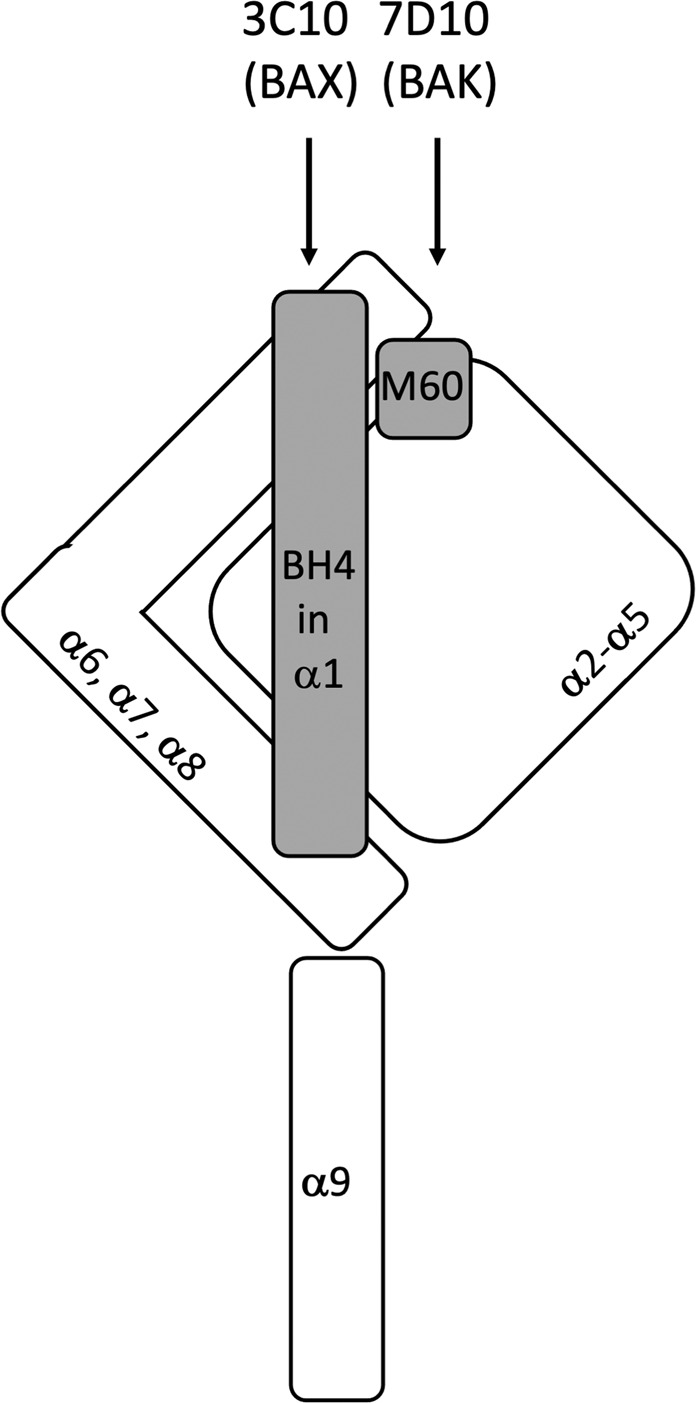

Striking similarities between this crystal structure of BAK bound to an activating antibody and that of BAX bound to a similarly-acting antibody [13] are evident. In both cases, the antibody caused dissociation of epitopes from the globular folds of BAK or BAX, abstracting residues that participate in stabilising the inactive fold. The remaining globular folds of BAK and BAX both exhibited poor quality of the electron density compared to the bound antibody fragments, with crystallography requiring the use of functionally compromised mutants (BAKL100A, BAXP168G). The two antibody complexes differ i the nature of the resulting disturbance in the structures of apo-BAK/BAX (Fig. 7). However, in both cases the structures are consistent with a model whereby activation of these apoptotic effectors, whether by antibodies or some other means such as BH3-only proteins or small molecules, destabilises the inactive conformer, allowing transition to a membrane-permeabilising state.

Fig. 7. Schematic of BAK activation by the 7D10 antibody.

Non-activated BAK is shown with α9 inserted in the mitochondrial outer membrane. The α2-α5 core and α6-α8 latch are stabilised by contacts with both the BH4 domain (34VFRSYV39 in α1) and the M60 residue (in α1-α2 loop). The 7D10 antibody binds to 51GVAAPAD57 residues in the α1-α2 loop to trigger activation by disrupting M60’s linchpin role. In mitochondrial BAX the 3C10 antibody binds to a similar region, but triggers activation by disrupting contact with the BH4 domain [13].

What particular aspect of the interaction between BAK and 7D10 de-stabilises BAK? Prior studies, including comparison with the anti-BAX antibody 3C10 [13], suggested an effect on helix α1, including the BH4 domain. The crystal structure of 7D10 in complex with BAK does not support a model comparable to 3C10 with BAX because the BAK α1 is unperturbed by 7D10-binding. Instead, it suggests that the trigger for partial unfolding is the altered conformation of the epitope residues and the removal of the adjacent M60 from a binding pocket formed from helices α1, α5 and α6. This hypothesis is supported by the several properties of M60 mutants including altered dynamics (Fig. 4), altered melting temperature (Fig. 5a), increased susceptibility to proteolysis (Fig. 5b), and sensitisation to activation by heat and BID (Figs. 6, S5). Elements of the epitope itself may also contribute to stability of the monomer, as summarised in Table 1.

The data suggest a linchpin role for M60 in stabilising the monomeric inactive state of BAK prior to an activating stimulus (Fig. 7). The M60F and M60W increase contacts between the α1-α2 loop and elements of α1, the core (α2-α5) and latch (α6-α8) domains, stabilising the inactive fold and densensitising BAK from activation, while the M60A and M60G mutants decrease these same contacts and sensitise BAK for activation. Whether BH3-only protein activators of BAK trigger similar changes (i.e. decreased contact of M60 with α1, α5, α6) remains to be seen. Crystal structures of BAK bound to BH3 peptides frequently show M60 in the configuration seen in inert BAK (Table 1), but the sequence of events that lead to activation by BH3-only proteins remain poorly understood.

Based on NMR studies with stapled peptides, it has been proposed that the α1-α2 loop of BAX is part of a trigger site for its activation [27, 28], and crystallographic studies have been the basis for an allosteric model of BAX where the ensemble of BAX conformers, including its α1-α2 loop, determine its function [13]. Similar allosteric properties have recently been ascribed to the α1-α2 loop of BAX to explain mutational data that affect either BAX stability or its capacity to integrate with the mitochondrial outer membrane [29, 30]. In these examples, it is allostery without conformational change [31] that underpins the model. Here, for BAK, we report an example of allostery with conformational change. For example, we demonstrate a direct structural connection between the α1-α2 loop and the sensitivity of BAK to activation by BH3-only proteins on mitochondria. M60, acting remotely from the site where BH3-only proteins initiate BAK activation, provides a brake to that activation.

In summary, common to the mechanisms of activation of BAK by 7D10 and BAX by 3C10 is that the antibodies disrupt interactions characterising the inert, monomeric structures, thereby lowering the energy barrier to transition to symmetric, BH3-in-groove dimers and permeabilisation of the mitochondrial outer membrane. In particular, in the case of BAK, elements of the α1-α2 loop, especially the linchpin residue M60, directly contribute to the stability of the monomer. Small molecules targeting that site may be useful triggers of apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Recombinant protein expression and purification

BAKΔN22ΔC25Δcys wild-type, BAKΔN22ΔC25ΔcysL100A protein and other mutants were produced as described [16]. Here and elsewhere Δcys means replacement of wild-type cysteine residues with serine. BAKΔN22ΔC25Δcys C-terminal His tag construct was cloned into pTYB1, and all other BAK constructs were cloned into the pGEX 6P3 vector and the corresponding plasmids were transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells and grown in Super Broth (induction at OD (600 nm) = 1 with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37 °C). GST-tagged proteins were purified as follows. Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1.5 µg/mL DNase I (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Supernatants were passed over glutathione resin (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and the GST-tag removed by proteolysis using HRV-3C protease (1 mL at 0.2 mg/mL) overnight at 4 °C. BAK proteins were eluted as the flowthrough using lysis buffer without the DNase. Cells expressing BAKΔN22ΔC25Δcys C-terminal His tag were lysed in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and the clarified supernatant passed over a chitin binding column, washed with the same buffer and then treated with 50 mM DTT on the column (48 h at 4 °C) to chemically cleave the chitin tag. All proteins were further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex S75 10/300) in TBS (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) at 4 °C and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Thawed BAKΔN22ΔC25ΔcysL100A was applied again on a gel filtration column (Superdex 75 10/300, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) in TBS prior to complex formation for crystallisation trials.

A thrombin cleavage site was introduced into BAKΔN22ΔC25Δcys by substituting the BAK residues 61–67 (VTLPLQP) with the sequence LVPRGSP [26]. This construct, BAKth, was further modified by the point mutation M60A. These constructs were expressed and purified as GST fusions as described above, and the protein (1 mg/mL (10 μg)) was incubated with thrombin protease (0.1 units, Sigma, cat#10602400001) overnight at 4 °C prior to running on SDS-PAGE.

7D10 Fv fragments were recombinantly produced as extracellular proteins using the Brevibacillus Expression system II (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan) according to the commercial protocol. 7D10 sequences (patent WO/2015/176104) of the variable heavy and light chain domains were cloned into pNCMO2 vector as single fragments. A cleavable His tag (8× His) was added at the C-terminus of the heavy chain fragment. Light and heavy chain fragment plasmids were separately transformed into Brevibacillus competent cells and then inoculated together into 2SY media supplemented with 2% glucose and 50 µg/mL neomycin, to enable the heterodimerisation of light and heavy chain and minimise homodimeriation of the light chains, for 20 h at 30 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded on a Nickel column (5 mL CompleteTM His-Tag Purification Column, Roche, #cat6781535001) equilibrated in TBS. Correctly associated Fv complexes were separated from extracellular proteins and some light chain fragment dimers. 7D10 fragments were eluted with 100 mM imidazole in TBS. The His tag was removed using TEV protease and reapplied to the Nickel column before a second purification step on gel filtration column (Superdex S75 10/300, Cytiva) in TBS. 7D10 fragments were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Thermal shift assays

Thermal shift assays were performed to determine the relative stability of the BAK single point mutants compared to the wild-type protein. Protein was mixed with SYPRO® Orange (1:550 dilution, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) in TBS at a final concentration of 16 µM and final volume of 22 µL. A temperature gradient of 1°/min from 25 °C to 95 °C was applied to the samples and fluorescence measured at every degree using the FRET channel of a C1000 thermocycler equipped with a CFX384 Real-Time System fluorescence reader (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). The melting temperature (Tm) of each sample was calculated by fitting the data with the Boltzmann sigmoidal model in GraphPad Prism (v8.4.3) and determining the inflection point. Melting curves were measured in duplicate the following number of times for each construct – WT (n = 7), M60A, M60G (n = 5), M60L, M60W, M60F (n = 3), L100A (n = 4).

Liposome release assay

Liposomes were prepared as previously described [32]. Briefly, liposomes were made with mole percent mixtures of 43.8% 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 23.8% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE), 10.5% L-α-phosphatidylinositol from bovine liver (PI), 9.5% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine, 7.6% 1′,3′-bis[1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-sn-glycerol (Cardiolipin), 4.8% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[(N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid)succinyl] nickel salt (DGS-NTA(Ni)). All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Lipids were dissolved in chloroform and 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene before mixing at the above ratios and drying under N2 gas. Lipid mixtures were resuspended in 50 mM self-quenching 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein. Resuspended lipids were frozen and thawed several times and then extruded an odd number of times (more than 20) through a membrane with a pore size of 100 nm and stored at 4 °C. Excess dye was removed from the liposomes using a PD10 column just before use.

Human BID BH3 peptide (H-SESQEDIIRNIARHLAQVGDSMDRSIPPGLVNGL-NH2) and BIM BH3 peptide (Ac-DMRPEIWIAQELRRIGDEFNAYYARR-NH2) were purchased from GenScript. His-tagged BAK was mixed with increasing concentrations of activator (7D10 antibody, 7D10 Fv, or BID/BIM BH3 peptide) and 5 µM of liposomes in a final reaction volume of 150 µl per well in Falcon 96-well U-bottom tissue culture plates (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). Fluorescence was measured every 2 mins (excitation at 485 nm, emission at 535 nm) in a Chameleon V plate reader (LabLogic Systems, Sheffield, UK) for a total of 2 h. Experiments were performed three times, and at least two technical replicates were averaged for each sample per experiment. Baseline release values from each liposome mixture in SUV were subtracted from samples. Data were normalised to dye release from liposomes treated with CHAPS.

Crystallisation and crystallography

Complexes were produced by mixing BAKΔN22ΔC25Δcys, wild-type or L100A, in twofold excess with 7D10 Fv and purifying on a gel filtration column (Superdex S75 10/300, Cytiva) in TBS. The BAKΔN22ΔC25ΔcysL100A:7D10 Fv complex (8 mg/ml) crystallised from 40% MPD, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 6.44) and 5% polyethylene glycol 8000. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Australian Synchrotron on beamline MX1 (Table 2). The structure was solved with PHASER [33], first finding four copies of an Fv search model from the anti-BAX antibody 3C10 [13]. Iterative model building in COOT [34] allowed placement of four BAK molecules and subsequent refinement was in PHENIX [35] with non-crystallographic symmetry restraints (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for BAK L100A complex with the Fv fragment of antibody 7D10 (PDB entry 7LK4).

| Data collection | |

|---|---|

| Space Group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 57.48, 272.48, 74.34 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90 91.8 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 48.56–3.1 (3.21–3.10) |

| Rmerge | 0.190 (1.058) |

| Rmeas | 0.225 (1.258) |

| Rpim | 0.119 (0.671) |

| I/σ(I) | 6.8 (1.2) |

| CC1/2 | 0.98 (0.43) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.5 (98.1) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.4–3.1 (3.19–3.10) |

| No. reflections | 40131 (3207) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.214 (0.329) 0.262 (0.355) |

| No. atoms | 11734 |

| Protein | 11716 |

| Ligand | 0 |

| Water | 18 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 86 |

| Ligand | N/A |

| Water | 72 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.533 |

Computational studies

The MODELLER (v9.24) [36] program was used to generate all BAK models, including apo-wild-type, apo-mutant, and BAK in complex with the 7D10 Fv. Models of apo-BAK used the x-ray structure of BAK [15] (2IMS, residues L19-L181 with seleno-methionine replaced with methionine) as a template to introduce individual point-mutations. Models of monomeric BAK in complex with 7D10 Fv were assembled by grafting onto the x-ray structure of apo-BAK the epitope region and associated Fv from the crystal structure of the complex presented here (PDB 7LK4); these models allowed the 7D10 Fab to engage the BAK α1-α2 loop epitope whilst retaining M60 in the α1α5α6 binding pocket. Models with the lowest MODELLER objective function were used to seed MD simulations, ten replicas for apo simulations and five for those in complex with the 7D10 Fab.

Independent sets of MD simulations were conducted using the GROMACS (v2019.3) suite [37] with the CHARMM36m force field [38]. Protein systems were simulated in solvated TIP3P cubic boxes extended 10 Å beyond all protein atoms. Sodium and chloride ions were included to neutralise the system and attain an ionic strength of 0.1 M. The temperature of the protein and solvent was coupled independently to a velocity rescaling [39] thermostat applying a coupling time of 0.1 ps at 300 K. The pressure of the system was maintained against a reference of 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat [40] using a coupling time of 2.0 ps. Van der Waals interactions used a cut-off of 12 Å, and the potential-switch-Verlet modifier to ensure the potential is zero at the cut-off distance. The particle-mesh Ewald method [41] was used for electrostatic interactions within a similar cut-off of 12 Å. Neighbour searching made use of the Verlet grid cut-off scheme, update every 100 steps (following usual practice when using GPU hardware for calculations). Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions. Hydrogen bond lengths were constrained with the P-LINCS algorithm [42] allowing a 2 fs time step integration. Simulations were first energy minimised to a maximum of 50,000 steps using the steepest descent minimisation protocol prior to 200 ps positionally restrained equilibration conducted firstly in the canonical ensemble, and subsequently isothermal-isobaric ensemble. Simulations were continued for either 1 or 2 µs for apo-BAK and BAK:7D10 complexed simulations, respectively.

Analysis of MD simulations made use of built-in GROMACS and VMD [43] utilities, removing global rotation and translation, and discarding the first 100 ns of each replicate trajectory as equilibration. Assessment of protein flexibility utilised the GROMACS gmx trjconv and rmsf utilities, via a least-square fit prior to determining the root mean square fluctuation of protein atoms with gmx rmsf. The principal components relating significant motions in the simulations of BAK were calculated on BAK C-alpha atoms using the ProDy utility interfaced in VMD using the Normal Mode Wizard [44]. Eigenvectors describing significant motions associated with eigenvalues whose magnitudes describe the largest magnitude of motion [45] described the essential correlated protein motions observed in the simulations. The Normal Mode Wizard utility was subsequently used to calculate the mean square fluctuation of each eigenvector as a product of each C-alpha atom.

The DUET webserver [25] was used to estimate the in silico effect of the M60A and M60G mutations on BAK. The DUET webserver combines the mCSM and SDM techniques in predicting changes in the Gibbs free energy due to amino acid substitution.

Cloning and expression of full-length BAK variants in cells

Full length human BAK mutants (Δcys and Δcys M60A/G) were generated using primers or gBlock gene fragments (Integrated DNA Technologies, Newark, NJ, USA). PCR products or gene fragments were digested with EcoRI and XhoI and cloned into the pMX-IRES-GFP retroviral expression vector, and those mutations introduced via overlap extension PCR confirmed by DNA sequencing. BAK variants were then stably expressed in SV40-immortalised Bak−/−Bax−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts [11], and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% Foetal Bovine Serum, 0.1 mM L-asparagine and 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol at 37 °C in a humidified 10% CO2 incubator. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination.

cBID-activation of BAK in permeabilised cells

BAK-expressing mouse embryonic fibroblasts were permeabilised by resuspension in Fractionation buffer (20 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM sucrose, 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 0.025% w/v digitonin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA #300410), 1× Complete protease inhibitor (Roche #11836145001), and 4 mg/mL pepstatin A (Sigma #P5318), followed by incubation for 10 min at 4 °C.

For activation of BAK and mitochondrial cytochrome c release, permeabilised cells (50 μl) were supplemented with increasing doses of caspase-8-cleaved human BID (cBID) diluted in Fractionation buffer supplemented with 1% BSA [46] and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. Reactions for flow cytometry were spun at 600 g, and washed 2× in fractionation buffer. Reactions for western blot were fractionated at 13,000 g, before addition of SDS PAGE buffer.

Detection of BAK activation and cytochrome c release by flow cytometry

Permeabilised cells were resuspended in Fixation buffer (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA, USA #00–5523) for 30 min at 4 °C prior to two washes with Permeabilisation buffer (Ebioscience, #00–5523). Cells were then stained by resuspension in antibody to activated BAK (1:1,600, mouse monoclonal clone G317-2, #556382 BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) diluted in Permeabilisation buffer and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice with Permeabilisation buffer and then stained for 30 min at 4 °C with goat anti-mouse-pacblue (1:200, #P31582, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA, AB_10374586) together with anti-cytochrome c-APC (1:50, clone REA702, #130–111–368, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Stained cells were washed twice in Permeabilisation buffer and analysed on a FACS Fortessa (BD Biosciences) before data analysis (FlowJo software).

Detection of BAK levels and cytochrome c release by western blotting

Supernatant and permeabilised cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE (BioRad) and transferred to PVDF or nitrocellulose for staining of BAK/VDAC1 or cytochrome c, respectively. Primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal anti-BAK aa23–38 (1:5,000, #B5897; Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-VDAC1 (1:1,000, AB10527, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-cytochrome c (1:2,000, #556433, BD Biosciences), with detection by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:5,000, #4010–05, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and anti-mouse (1:2,000, #1010–05, Southern Biotech) secondary antibodies.

Supplementary information

Related files - western blot gels for Fig S5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mike Lawrence and Mai Margetts for advice, reagents and protocols for the Brevibacillus expression system II. We acknowledge support of the staff at the Collaborative Crystallisation Centre and at the Australian Synchrotron beamline MX1.

Author contributions

AYR, MSM, SI, MXS, AZW, DL, NAS and RWB designed and performed experiments, BJS, PEC, RMK and PMC designed and supervised experiments, wrote the paper with input from all the authors. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

Our work is supported by the NHMRC through fellowships (1116934 to PMC, 1079700 to PEC) and grants (1113133, 2001406, 1141874) the Australian Cancer Research Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (US) (SCOR grant 7001–03), Lady Tata Memorial Trust Fellowship (SI), Jack Brockhoff Foundation and Marian and E.H. Flack Trust Early Career Research Grant (SI), the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and the Australian Government NHMRC IRISS (9000587). Part of this work used resources from the National Computational Infrastructure, which is supported by the Australian Government and provided through Intersect Australia under LIEF grants LE170100032 and through the HPC-GPGPU Facility which was established with the assistance of LIEF grant LE170100200.

Data availability

PDB entry 7LK4 is presently on hold at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/pdb/7lk4.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Edited by G. Melino

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Adeline Y. Robin, Michelle S. Miller.

Contributor Information

Ruth M. Kluck, Email: kluck@wehi.edu.au

Peter M. Colman, Email: pcolman@wehi.edu.au

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41418-022-00961-w.

References

- 1.Czabotar PE, Lessene G, Strasser A, Adams JM. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:49–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu YT, Youle RJ. Bax in murine thymus is a soluble monomeric protein that displays differential detergent-induced conformations. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10777–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewson G, Kluck RM. Mechanisms by which Bak and Bax permeabilise mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2801–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouwer JM, Westphal D, Dewson G, Robin AY, Uren RT, Bartolo R, et al. Bak core and latch domains separate during activation, and freed core domains form symmetric homodimers. Mol Cell. 2014;55:938–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czabotar PE, Westphal D, Dewson G, Ma S, Hockings C, Fairlie WD, et al. Bax Crystal Structures Reveal How BH3 Domains Activate Bax and Nucleate Its Oligomerization to Induce Apoptosis. Cell. 2013;152:519–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewson G, Kratina T, Sim HW, Puthalakath H, Adams JM, Colman PM, et al. To trigger apoptosis, Bak exposes its BH3 domain and homodimerizes via BH3:groove interactions. Mol Cell. 2008;30:369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewson G, Ma S, Frederick P, Hockings C, Tan I, Kratina T, et al. Bax dimerizes via a symmetric BH3:groove interface during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:661–70. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, et al. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llambi F, Moldoveanu T, Tait SW, Bouchier-Hayes L, Temirov J, McCormick LL, et al. A unified model of mammalian BCL-2 protein family interactions at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2011;44:517–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyer S, Anwari K, Alsop AE, Yuen WS, Huang DC, Carroll J, et al. Identification of an activation site in Bak and mitochondrial Bax triggered by antibodies. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11734. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell. 2000;103:645–54. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robin AY, Iyer S, Birkinshaw RW, Sandow J, Wardak A, Luo CS, et al. Ensemble Properties of Bax Determine Its Function. Structure. 2018;26:1346–59 e1345. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kvansakul M, Yang H, Fairlie WD, Czabotar PE, Fischer SF, Perugini MA, et al. Vaccinia virus anti-apoptotic F1L is a novel Bcl-2-like domain-swapped dimer that binds a highly selective subset of BH3-containing death ligands. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1564–71. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moldoveanu T, Liu Q, Tocilj A, Watson M, Shore G, Gehring K. The X-ray structure of a BAK homodimer reveals an inhibitory zinc binding site. Mol Cell. 2006;24:677–88. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwer JM, Lan P, Cowan AD, Bernardini JP, Birkinshaw RW, van Delft MF, et al. Conversion of Bim-BH3 from Activator to Inhibitor of Bak through Structure-Based Design. Mol Cell. 2017;68:659–72 e659. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chikh GG, Li WM, Schutze-Redelmeier MP, Meunier JC, Bally MB. Attaching histidine-tagged peptides and proteins to lipid-based carriers through use of metal-ion-chelating lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1567:204–12. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee EF, Dewson G, Smith BJ, Evangelista M, Pettikiriarachchi A, Dogovski C, et al. Crystal structure of a BCL-W domain-swapped dimer: implications for the function of BCL-2 family proteins. Structure. 2011;19:1467–76. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence MC, Colman PM. Shape Complementarity at Protein-Protein Interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:946–50. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epa VC, Colman PM. Shape and electrostatic complementarity at viral antigen-antibody complexes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;260:45–53. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05783-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alsop AE, Fennell SC, Bartolo RC, Tan IK, Dewson G, Kluck RM. Dissociation of Bak alpha1 helix from the core and latch domains is required for apoptosis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6841. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Takemoto C, Akasaka R, Uchikubo-Kamo T, Kishishita S, Murayama K, et al. Novel dimerization mode of the human Bcl-2 family protein Bak, a mitochondrial apoptosis regulator. J Struct Biol. 2009;166:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tandon H, de Brevern AG, Srinivasan N. Transient association between proteins elicits alteration of dynamics at sites far away from interfaces. Structure. 2021;29:371–84 e373. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pires DE, Ascher DB, Blundell TL. DUET: a server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability using an integrated computational approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W314–319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birkinshaw RW, Iyer S, Lio D, Luo CS, Brouwer JM, Miller MS, et al. Structure of detergent-activated BAK dimers derived from the inert monomer. Mol Cell. 2021;81:2123–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavathiotis E, Reyna DE, Davis ML, Bird GH, Walensky LD. BH3-triggered structural reorganization drives the activation of proapoptotic BAX. Mol Cell. 2010;40:481–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gavathiotis E, Suzuki M, Davis ML, Pitter K, Bird GH, Katz SG, et al. BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature. 2008;455:1076–81. doi: 10.1038/nature07396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dengler MA, Gibson L, Adams JM. BAX mitochondrial integration is regulated allosterically by its alpha1-alpha2 loop. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:3270–81. doi: 10.1038/s41418-021-00815-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dengler MA, Robin AY, Gibson L, Li MX, Sandow JJ, Iyer S, et al. BAX Activation: Mutations Near Its Proposed Non-canonical BH3 Binding Site Reveal Allosteric Changes Controlling Mitochondrial Association. Cell Rep. 2019;27:359–73 e356. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper A, Dryden DTF. Allostery without Conformational Change - a Plausible Model. Eur Biophys J Biophy. 1984;11:103–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00276625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowan AD, Smith NA, Sandow JJ, Kapp EA, Rustam YH, Murphy JM, et al. BAK core dimers bind lipids and can be bridged by them. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:1024–31. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0494-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–74. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb B, Sali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using Modeller. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016;54:5.6.1-5.6.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Pall S, Smith JC, Hess B, et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1-2:6. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J, Rauscher S, Nawrocki G, Ran T, Feig M, de Groot BL, et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods. 2017;14:71–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parrinello M, Rahman A. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Appl Phys. 1981;52:9. doi: 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz M, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:19. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess B. P-LINCS: A Parallel Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:116–22. doi: 10.1021/ct700200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakan A, Meireles LM, Bahar I. ProDy: protein dynamics inferred from theory and experiments. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1575–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amadei A, Linssen ABM, Berendsen HJC. Essential Dynamics of Proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:412–25. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uren RT, Dewson G, Chen L, Coyne SC, Huang DC, Adams JM, et al. Mitochondrial permeabilization relies on BH3 ligands engaging multiple prosurvival Bcl-2 relatives, not Bak. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:277–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Related files - western blot gels for Fig S5.

Data Availability Statement

PDB entry 7LK4 is presently on hold at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/pdb/7lk4.