Abstract

Cryptococcosis is a global fungal infection caused by the Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii yeast complex. This infection is acquired by inhalation of propagules such as basidiospores or dry yeast, initially causing lung infections with the possibility of progressing to the meninges. This infection mainly affects immunocompromised HIV and transplant patients; however, immunocompetent patients can also be affected. This review proposes to evaluate cryptococcosis focusing on studies of this mycosis in Brazilian territory; moreover, recent advances in the understanding of its virulence mechanism, animal models in research are also assessed. For this, literature review as realized in PubMed, Scielo, and Brazilian legislation. In Brazil, cryptococcosis has been identified as one of the most lethal fungal infections among HIV patients and C. neoformans VNI and C. gattii VGII are the most prevalent genotypes. Moreover, different clinical settings published in Brazil were described. As in other countries, cryptococcosis is difficult to treat due to a limited therapeutic arsenal, which is highly toxic and costly. The presence of a polysaccharide capsule, thermo-tolerance, production of melanin, biofilm formation, mechanisms for iron use, and morphological alterations is an important virulence mechanism of these yeasts. The introduction of cryptococcosis as a compulsory notification disease could improve data regarding incidence and help in the management of these infections.

Keywords: Cryptococcosis, Epidemiology, Antifungal treatment, Virulence mechanism

Introduction

Cryptococcosis is a globally widespread and endemic fungal infection caused by the Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii yeast complex. Identified as an opportunistic disease, the infection caused by C. neoformans affects mainly acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients; on the other hand, C. gattii infection affects predominantly immunocompetent individuals, being endemic in North and Northeast Brazil and reaching human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) negative children, adolescents, and young adults [1]. Worldwide, between 200,000 and 300,000 new cases of HIV-associated cryptococcosis are reported each year, with approximately 180 thousand deaths [2].

This disease is not a condition of compulsory notification in Brazil, and groups of Brazilian researchers studied the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of this infection in the country independently. Efforts to unite information were made in the 2000s, and the creation of the Cryptococcoses Brazil Network contributed to data systematization, in research projects, academic training, and improvement in health services. However, with the development of national legislation that regulates its notification, the expectation of new perspectives on cryptococcosis in Brazil could become more evident [3]. This review proposes to evaluate aspects of cryptococcosis focusing on studies of this mycosis in Brazilian territory; moreover, with recent advances in the understanding of its virulence mechanism, animal models in research are also evaluated.

Epidemiology

Cryptococcosis is a systemic fungal infection, globally disseminated and endemic in northeastern Brazil, Paraguay, Mexico, Australia, India, Southeast Asia, Europe, California (USA), and several African countries [4]. Initially, cryptococcosis was a disease that appeared to affect mainly immunocompromised individuals. However, an outbreak in healthy individuals in North America and Canada, known as the Pacific Northwest outbreak, calls attention to the ability of some strains of the fungus to act as primary pathogens [5, 6]. Despite being an omnipresent disease, its epidemiology is not widely known [7].

Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii complex fungi are the agents of cryptococcosis. The infection starts with the inhalation of airborne propagules, such as basidiospores or dry yeasts. The pathogen establishes itself in the lungs, where it can survive and proliferate within the alveolar macrophages [8]. There are reports that the infection can occur in childhood with unrecognized pneumonia. However, it is controlled by the immune system until immunosuppression occurs because yeast cells remain dormant and infection is latent [9].

Because Cryptococcus spp. can prolong their latency in host cells and most humans have contact with the microorganism in early childhood, it is assumed that most clinical cases represent reactivation of a long-standing asymptomatic infection. Thus, the disease can be triggered, for example, when the CD4 + T cell count decreases in infected individuals [6]. The proportion of clinical disease represented by reactivation of latent disease versus primary infection is unknown in HIV-positive individuals, but a study in patients with cryptococcosis after solid organ transplant found that only 52% of infections were due to reactivation [10], suggesting that the view of cryptococcosis as a reactive infection may not be accurate.

In 2014, the global estimate of HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis was 223,100 cases. Of these, Latin America stood out as the third-largest number (5300 cases per year). Brazil and Colombia stand out as the countries with the highest incidence (1001 to 2500 cases), followed by Argentina and Mexico (501 to 1000 cases) [2].

In Brazil, cryptococcosis has been identified as one of the most lethal fungal infections among HIV patients [11]; however, accurate estimates of the incidence of this infection are not available because the notification is not mandatory to date. In particular, an average annual incidence of 0.45 cases of meningeal cryptococcosis per 100,000 inhabitants was reported in the general population of the state of Rio de Janeiro—RJ [4].

Although the C. neoformans/C. gattii species complex has a worldwide distribution, some molecular types seem to prevail in certain regions. Currently, five major molecular types are recognized within the C. neoformans species complex: VNI, VNII, and VNB, all presenting capsular antigen A (serotype A) and classified as C. neoformans var. grubii; VNIV presenting the capsular antigen D (serotype D) and classified as C. neoformans var. neoformans; and VNIII, which represents diploid and aneuploid hybrids between the two varieties (AD hybrids). The Cryptococcus gattii species complex includes at least four molecular types: VGI (serotype B), VGII (serotype B), VGIII (serotype B or C), and VGIV (most serotype C) [12].

The VNB genotype first described as geographically restricted to Botswana [13] was found in other places. Phylogenetic and population genomic analyzes of isolates from Brazil revealed that this strain previously “African” occurs naturally in the South American environment [7].

By 2013, about 10% of more than 68,000 Cryptococcus isolates reported in the literature had been molecularly typed [14]. Additional strains probably will be found if more strains are analyzed and their relationships with existing isolates are established. As a result, the names “C. neoformans species complex” and “C. gattii species complex” have been proposed to indicate that both species contain genetically diverse lineages. It may be premature to draw boundaries between them to guarantee each one as a separate species. The status of the “species complex” was provisional because of the stability of nomenclature until the vast majority of cryptococcal populations are analyzed, and the character of each strain becomes readily identifiable [15, 16].

The C. neoformans/C. gattii species complex is present in different ecological niches, such as soil, bird droppings, and tree hollows. C. neoformans is often associated with bird excretion, especially in wild pigeons, which appears to be a relevant mechanical source to disperse the fungus in densely populated urban areas [17, 18]. This species is also present in plant materials [19]. The VNI strain is mainly associated with avian excrement, while the VNB strain is found predominantly in association with specific tree species [7]. Studies of the ecological niches of C. gattii have shown that different species of trees can harbor this fungus [19–21]. Based on these data, it is possible to infer that C. gattii is not associated with a specific tree genus but has a predilection for plant and wood remains in general.

Environmental sources of Cryptococcus spp. have been identified in some Brazilian states. The presence of the fungus in trees and bird droppings has already been reported in the cities of Rio de Janeiro (RJ) [22], Teresina (PI) [23], Boa Vista and Maracá Island (RR) [24], Manaus (AM) [25], Campo Grande (MS) [26], Sapucaia do Sul (RS) [17], Cuiabá (MT)[20], and Belém (PA) [27] e São Paulo (SP)[28]. Studies have shown C. gattii in wooden houses in the Amazon region (prevalence of 5.9%) [29]. Despite this finding, in most Brazilian states, occurrences of Cryptococcus spp. were not estimated. The observation of the correlation between environmental and clinical isolates is also limited, which decreases the power of statistical association [1, 30, 31].

The genotypes correlate with cryptococcal phenotypes and clinical presentation impaction in the therapy surveillance and prophylactic actions [32], this issue will be discussed in a further session. With the aim of knowing the distribution of the genotypes of Cryptococcus spp. in Brazilian states, researchers used different methodologies to identify molecular types in clinical, environmental, and veterinary samples.

Studies carried out between 2004 and 2020 evaluated genotypes in clinical samples from 1204 patients. Among them are immunocompromised individuals (AIDS patients, transplanted, on long-term use of corticosteroids) and immunocompetent. The prevalence of genotypes in clinical samples from twelve Brazilian states was 80.07% for C. neoformans VNI; 5.73% for C. neoformans VNII; 0.17% for C. neoformans VNIV; and 0.33% for C. neoformans VNB. For C. gattii, the prevalence found was 0.42% for VGI, 12.79% for VGII, and 0.50% for VGIII [11, 30, 33–51]. Table 1 shows the molecular types found in each study.

Table 1.

Studies addressing the prevalence of Cryptococcus molecular type clinical strains isolated in Brazil

| Autor | Location—state | Tota of clinical sample evaluated | Molecular typing | Frequency of genotypes found | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. neoformans VNI | C. neoformans VNII | C. neoformans VNIV |

C. gattii VGI |

C. gattii VGII |

C. gattii VGIII |

C. neoformans VNB |

||||

| [52] | Ribeirão Preto—SP | 72 | URA5 RFLP | 61 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| [49] | Uberaba—MG | 23 | MLST, URA5 RFLP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| [45] | São Paulo—SP | 59 | MLST | 40 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 |

| [51] | Porto Alegre—RS | 15 | URA5 RFLP | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| [38] | SP, MG, PR | 191 | AFLP fingerprinting | 172 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| [30] | Uberaba—MG | 63 | MLST, URA5 RFLP | 57 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| [11] | MS | 129 | URA5 RFLP | 115 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| [33] | Uberlândia—MG | 41 | URA5 RFLP | 40 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| [35] | Ribeirão Preto—SP | 20 | PCR fingerprint | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| [34] | Cuiabá—MT | 27 | URA5 RFLP, PCR fingerprint | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| [47] | Campo Grande—MS | 48 | URA5 RFLP | 45 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| [42] | Bahia—BA | 62 | URA5 RFLP | 48 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| [40] | Amazonas—AM | 40 | URA5 RFLP | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| [41] | Teresina—PI | 63 | URA5 RFLP | 37 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| [37] | Amazonas | 57 | URA 5 RFLP, PCR fingerprint | 39 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| [44] | Uberaba—MG | 81 | URA5 RFLP | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| [53] | Goiânia—GO | 84 | PCR fingerprint | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| [46] | Belém—PA | 43 | URA 5 RFLP, PCR fingerprint | 22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| [39] | Rio de Janeiro—RJ | 88 | PCR fingerprint RAPD | 73 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Total of molecularly typed clinical samples | 1204 | 80.07% | 5.73% | 0.17% | 0.42% | 12.79% | 0.50% | 0.33% | ||

AM Amazonas, BA Bahia, GO Goiânia, MG Minas Gerais, MS Mato Grosso do Sul, PA Pará, PE Pernambuco, PI Piauí, PR Paraná, RS Rio Grande do Sul, RR Roraima, SP São Paulo

In Porto Alegre—RS, a different prevalence was observed for the molecular type VNII, with an occurrence of 69.2% in patients with HIV [51]. The small number of samples evaluated (n = 15) may cause this divergence. Another study that considered the genotypes of 443 clinical strains, 87 evaluated by the author [1] and 356 by other sources [22, 39, 54–56], showed a genotypic variety similar to that considered in Table 1.

Primary cryptococcosis is mainly related to the molecular type VGII in North and Northeast in Brazil. This genotype has also been linked to a significant fraction of cases of infantile cryptococcosis in the states of Amazonas [37], Pará [46], Piauí, and Maranhão [41]. The high frequency of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV-negative children in the North and Northeast of Brazil suggests that this infection occurs early in life in these regions. A study with 145 VGII isolates from the North, Northeast, Southeast, and Central-West showed that all Brazilian regions had a high diversity of haplotypes, the largest of which in the Northeast and the smallest in the Midwest [48]. Subsequently, high genetic variability was also in 23 clinical isolates of VGII from the Southeast region of Brazil [49].

Until the late 1970s, cryptococcosis was a rare infection that occurred in patients with lymphoma, sarcoidosis, liver disease, and transplant recipients [11, 31]. In the 1980s, a cryptococcal disease acquired a role as an opportunistic infection with the emergence of HIV infection. It increased rates of morbidity and mortality [4]. Oliveira-Netto et al. (1993), in one of the first retrospective studies in Brazil, they observed that of 308 cases that occurred between 1941 and 1992, more than half of them (179–59.3%) had occurred in the last 10 years, a period that coincided with the worldwide advance of infection by HIV.

Brazilian Health Surveillance Secretariat has recorded a decrease in the number of HIV infection cases in recent years. In 2012, a HIV decrease from 21.9/100,000 inhabitants to 17.8/100,000 inhabitants in 2019 was described, representing a decrease of 18.7%. The HIV mortality rate has shown a similar drop in the last 5 years (17.1%). However, the North and Northeast regions showed an upward trend in detection in the same period: in 2009, the rates recorded in these regions were 20.9 (North) and 14.1 (Northeast) cases per 100,000 inhabitants, while in 2019, they were 26.0 (North) and 15.7 (Northeast), representing increases of 24.4% (North) and 11.3% (Northeast). Despite the growing trend of HIV infection in the North and Northeast, most cryptococcosis studies are in the South and Southeast of Brazil. Only 25% of the clinical genotyping of Cryptococcus spp. in Table 1 were in states with a tendency to increase the incidence of HIV, which puts these regions in focus for future studies.

Cryptococcosis clinical features

Several case reports and case series of cryptococcal diseases have been published in Brazil in different clinical settings. In autopsy studies conducted in Latin America, patients with neurocryptococcosis, most of whom were infected with HIV, predominantly had disseminated forms of the disease, with multiple organ involvement [57]. In a study that included 4824 necropsies in a State of São Paulo hospital from 2000 to 2009 [58], cryptococcus disease was the most prevalent fungal infection, presenting as a disseminated disease in 34.5% of cases. Another study conducted in Minas Gerais [59] reviewed medical and necropsy records of 45 individuals with AIDS and cryptococcosis from 1989 to 2008, out of 1785 necropsies in the same period, and found 68.9% cases of disseminated infection. The most frequent clinical presentations were altered consciousness, increased intracranial pressure, and malnutrition.

A series of cases have been published recently in different regions of Brazil. Azambuja et al. [60] evaluated a retrospective cohort of seventy-nine cryptococcal meningitis cases in the tertiary care hospital in southern Brazil from 2009 to 2016. Most of the patients presented with positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures for Cryptococcus neoformans (96%). The most common underlying disease was HIV (82%), followed by solid organ transplants (10%). Fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, and altered mental status were the most common clinical manifestations. In the Southeast, Aguiar 2017 et al. [33] analyzed medical records of 41 patients diagnosed with a positive culture from 2004 to 2013, 85% of whom were diagnosed with AIDS. Most isolates presented the VNI genotype (97.5%) (serotype A, var. grubii), and one isolate was genotyped as C. gattii (VGI). The yeast was isolated from the CSF of 21 patients (51%), from the blood in 19.5%, and in 24% of patients, the agent was isolated from the CSF and blood. Meningoencephalitis was the most frequent (75%) manifestation of infection. Despite adequate treatment, the mortality of the disease was 58.5%. In the Pantanal region, a retrospective cohort of 129 cases of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis showed AIDS as an underlying disease in 89% of the cases, 76.6% were male, and the mortality rate was 46.5% [11].

HIV-infected patients (with Cryptococcus spp. infection) have been interestingly reported as presenting with the disseminated disease to the central nervous system and bone marrow [61]. Cases of fluconazole-resistant Cryptococcus neoformans in HIV-positive patients have been described [62, 63], as difficult to treat. De Oliveira et al. [62] described the specimen as a filamentous form, but no causal effect of the non-response and phenotypic form could be determined.

Solid-organ transplantation recipients are recognized as an important population at risk for cryptococcal disease [31, 45, 64]. Ponzio et al.[45] compilated clinical data of 60 renal transplant recipients over 29 years and found that 72 isolates (87.8%) were C. neoformans and 10 (12.2%) were C. gattii. The most common molecular types were VNI, VNII, VGII, VNB, and VNI/II, respectively, with 40 cases (66.7%); 9 cases (15%); 6 cases (10%); 4 cases (6.7%); and 1 case (1.7%). The overall mortality rate was 61% (VGII is associated with high mortality); fungemia and absence of headache were correlated with decreased survival in the cohort.

Other underlying conditions such as hematological diseases [65], corticosteroid use [31, 66, 67], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [66, 68], and advanced hepatic disease [31] have also been described as immunocompromising comorbidities leading to the special presentation of the cryptococcal disease as a disseminated disease, and co-infection with histoplasmosis [11]. A Cryptococcus larenttii fungemia-related case in a young critical patient with cervical cancer has been published [69].

Immunocompetent hosts are a challenging group of patients, as the underlying congruence of undiagnosed immune injuries, together with a lack of clinical data, contributes to management principles based on expert opinions [70, 71]. In Brazil, it has been recognized as a differential diagnosis for the cause of neoplasias in the mediastinum [68, 72], lungs [73, 74], and the CNS [74]. Extraordinary neurologic involvement has also been described in those hosts, as reported by Cavalcanti et al. [75] as the etiology of Kinsbourne syndrome during pregnancy, and acute parkinsonism in a 19-year-old woman [76]. Favalessa et al. [34] described a fatal case of cryptococcus meningitis caused by C. gattii; although caused by a multi-sensitive strain with the appropriate and opportune treatment provided, the patient died.

Lomes et al. [71] conducted a retrospective analysis of 29 cases of cryptococcal diseases in HIV-negative/non-transplant patients from 2007 to 2014 in a tertiary reference public hospital in São Paulo. Of those, 25 had CNS infection and four pulmonary involvements only. Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, solid organ neoplasm, hyper IgE syndrome with DOCK 8 deficiency, and cigarette smoking were identified. Regarding the clinical aspects, the major symptoms of patients with cryptococcal meningitis included headache and fever. Nine of the 11 patients with confirmed diagnoses of pulmonary cryptococcosis had symptoms such as cough, chest pain, dyspnea, and hemoptysis.

Cutaneous presentations of cryptococcosis assume special attention in Brazil, as they comprise many tropical diseases, such as leishmaniasis and cutaneous tuberculosis, as differential diagnoses or as contributing risk factors. Moretti de Lima et al. [67] described a case of malar lesion mimicking cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by the dissemination of cryptococcosis in a male carpenter during the treatment with prednisone of a type 2 leprosy reaction. Hayashida et al. [77] described four cases of dissemination to the skin in three renal transplant patients and one immunocompetent patient. Dora et al. [78] reported an intriguing case of disseminated disease by C. gattiii in an immunocompetent host presenting as nodular cutaneous lesions in the cephalic segment that progressed for 5 months and a month later presented as CNS symptoms. Cutaneous manifestation can also be primary, as described by Marques et al. [79] in a series of cases where the lesion predominated in the upper limb and trauma was the main risk factor.

Pediatric diseases constitute a special segment in cryptococcal disease in Brazil, especially in the north and northeast regions where the diseases caused by C. gattii are considered endemic. Corrêa et al. [80] described in the capital of Para state 19 children under 13 years of age with C. gattii disease from 1992 to 1998, all of them with meningoencephalitis, presenting with emesis and neck stiffness, and despite treatment, six of them died. Soares [81] reported a case of a 10-year-old boy with cerebral infection by C. gattii (fluconazole-resistant) that survived after adequate treatment. Martins et al. [30] reported a cohort study conducted in Teresina, capital of Piaui state, from 2008 to 2010, during which 13 of 63 cases of C. gattii disease in children up to 19 years of age, were all HIV negative and had a 38.4% mortality rate.

Studies demonstrated that Cryptococcus spp. genotypes can correlate with cryptococcal phenotypes and clinical presentation [32]. Primarily, C. neoformans complex causes infections in immunocompromised individuals while C. gattii complex infects immunocompetent individuals; however, within the species complex, there are varying degrees of genetic diversity resulting in different virulence and physiology attributes and changing the pathogenic specie pattern [32]. C. gattii VGI and VGII infect HIV-negative and immunocompetent individuals; on the other hand, VGIII and VGIV molecular type for example can infect primarily immunocompromised and HIV-infected individuals [32, 82]. In C. neoformans complex, VNI molecular type strains are associated with the phenotype of microcells, this morphology contributes to the dispersion of the cells to the CNS, and clinically, symptoms are vomiting and increased intracranial pressures [83]. The capsule size is also an important characteristic since it could affect the immune response, and increased capsule size is observed in VNI and VNB (subtype VNBI) [83]. In addition, VNI, VNBI, and VNBII are associated with lower CD4 counts and characteristics observed for infections caused by C. neoformans in immunocompromised patients [83]. VNB strains can cause cryptococcal meningitis and skin lesions and are associated with high mortality [84]. Espinel-Ingroff et al. (2012) [85] proposed differentiated epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFF) for C. neoformans VNI, VNIII, VNIV, and C. gattii VGI, VGII, and VGIII based on the assessment of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) for fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole obtained by different laboratories in Europe, USA, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Cuba, India, Mexico, and South Africa. This observation suggests that antifungal therapy should consider not only the drug used, but also the genotype of the Cryptococcus for successful treatment.

Cryptococcosis clinical management

Management of cryptococcus disease depends on the host features, organ involvement, and clinical presentation. It comprises antifungal therapy, relief of intracranial hypertension in CNS diseases, and even surgery in some cases [86]. The antifungal therapy in disease is divided into induction, consolidation, and maintenance (or secondary prophylaxis) phases. The induction phase aims to clear or strongly reduce the fungal burden, while the consolidation phase aims to maintain fungal negativity and normalization of clinical and laboratory parameters. The maintenance phase is provided in HIV-positive patients until immunologic recovery to prevent relapses; for 12 to 24 months and until the CD4 count reaches 100 to 200 cells [64, 87].

Although several newer antifungal agents have come to the pipeline recently, amphotericin, flucytosine, and fluconazole remain the cornerstone antifungal arsenal for the treatment of cryptococcal disease worldwide [64]. Amphotericin, a polyene drug, binds to ergosterol in the cell membrane, leading to pore formation and cell death, while flucytosine inhibits DNA replication and protein synthesis [85]. Fluconazole, a representant of the azole group, blocks the production of ergosterol in the biosynthesis pathway, specifically targeting lanosterol 14α-demethylase leading to the accumulation of a toxic sterol intermediate [88].

The latest Brazilian Cryptococcosis guidelines [87] divide therapeutic schemes into several categories: infection restricted to the lungs in the immunocompetent host, infections restricted to the lungs in the HIV-positive host, meningoencephalitis in the immunocompetent host, and meningoencephalitis or disseminated disease in HIV or other immunosuppressant conditions. In summary, minor situations are proposed to be treated with azoles (fluconazole or itraconazole) in the induction phase and the most severe situations with amphotericin deoxycholate (d-AMB) plus flucytosine in the induction phase for 2 weeks and maintenance with fluconazole 400 mg from 6 to 10 weeks or amphotericin and lipidic formulations alone as alternative schemes from 6 to 10 weeks. The guideline also makes recommendations for the management of intracranial hypertension considering the tomographic findings and lumbar puncture opening pressure, and a lumbar-peritoneal shunt is recommended in cases with hydrocephalus or persistent high opening pressure after 10 consecutive days of treatment. Similarly, the Brazilian guidelines for the management of the HIV infection from the Brazilian Ministry of Health [89] that addresses the CNS disease exclusively in this population recommend induction therapy with d-AMB plus flucytosine (or plus fluconazole) for at least 2 weeks, the use of lipidic formulations of amphotericin as an alternative to patients with toxicities when available, consolidation with fluconazole from 400 to 800 mg every day (qd) for at least 8 weeks, maintenance with fluconazole of 200 mg for at least 12 months, and two evaluations of CD4 counts of at least 200 cells with 6 months apart.

The latest Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines [64] for the management of cryptococcal disease recommend amphotericin in either the deoxycholate or lipidic formulation (depending on the population to be treated) plus flucytosine for 2 weeks as the primary option for induction treatment of meningoencephalitis in HIV-positive or transplant patients and 4 weeks for immunocompetent hosts. The fluconazole of 800 mg is suggested as consolidation for 8 weeks.

Recently, the Advancing Cryptococcal Meningitis Treatment for Africa trial [90], a phase III randomized controlled trial in an HIV-positive population with cryptococcus meningoencephalitis, found 1 week of amphotericin B given with flucytosine to be non-inferior to 2 weeks, flucytosine to be superior to fluconazole in association therapy, and found dual oral antifungal treatment with flucytosine and fluconazole to be a suitable alternative to intravenous treatment in resource-limited settings. In light of this data, the WHO guidelines for the management of cryptococcal diseases in HIV-infected adults [91] also recommend amphotericin associated with flucytosine, and fluconazole plus flucytosine, or fluconazole plus d-AMB as an alternative treatment in the induction phase, and the consolidation phase treatment retained as fluconazole of 800 mg for 8 weeks. Also, Jarvis et al. [90, 92] conducted a phase II randomized controlled study that has demonstrated that a single, high dose of 10 mg/kg of liposomal amphotericin is non-inferior to 14 days of daily 3 mg/kg treatment at clearing cryptococcus from the brain. Induction based on a single 10 mg/kg L-AmB dose is being taken forward to a phase 3 clinical endpoint trial.

Although Brazilian guidelines recommend flucytosine for antifungal therapy, this drug is not available in the country. This has been recognized as a critical contribution to the difficulty in reducing cryptococcosis mortality in Brazil [36, 93]. Beyond the lack of the availability of this drug in the country is the inability of most of the health facilities to afford the high cost of the amphotericin lipidic formulations, leading to nephrotoxicity and permanent kidney dysfunction or the need to change the therapy for suboptimal schemes [93, 94, 95]. Tuon et al. [94] conducted a retrospective pharmacoeconomic study in a Brazilian public hospital considering the direct cost of different antifungal therapies, chronic dialysis after discharge, and survival of 102 HIV-positive patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis, all treated with d-AMB. They found that treatment with amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC) would be cost-saving in comparison to d-AMB treatment if the early switch of treatment occurred in patients presenting acute kidney injury.

The antifungal drug resistance of Cryptococcus spp. in Brazil is described, among azole drugs, the resistance to fluconazole can reach 15% [45]. In southern Brazil, low susceptibility was described for fluconazole and flucytosine [38, 96] and itraconazole [35]. Susceptible Cryptococcus spp. antifungal profile was found in Northern Brazil report [97]. Moreover, the lack of correlation of the in vitro susceptibility and clinical outcome is questioned in HIV patients and the in vitro susceptibility determination clinical role is uncertain in the case of cryptococcal meningitis [98].

Another relevant workup issue that is worth commenting on is the availability of the Cryptococcal Antigen (CrAg) assays in an HIV-positive patient management setting. The WHO guidelines [91] recommend the use of the CrAg lateral flow or latex agglutination test as a diagnostic tool in CSF or even blood in resource-limited settings. Moreover, it also included the assay as a prevention strategy in screening for the risk of progression of disseminated disease in asymptomatic HIV-positive individuals with CD4 cell counts < 100. It may also be considered in individuals with CD4 counts < 200, in whom pre-emptive fluconazole therapy would be indicated after the exclusion of neurologic disease. The Brazilian Guidelines [87] also recommend this strategy for the CD4 threshold of < 100, but the broad use of this assay is limited by cost and lack of laboratory resources [99, 93]. Recently, Chagas et al. [98] describe the enumerations of Cryptococcus spp. cells at cerebrospinal fluid as a predictive indicator of patient outcome. According to the study, patients with CSF cells counting greater than 400 yeast cells/μ were associated with higher mortality.

Mechanisms that contribute to Cryptococcus spp. virulence

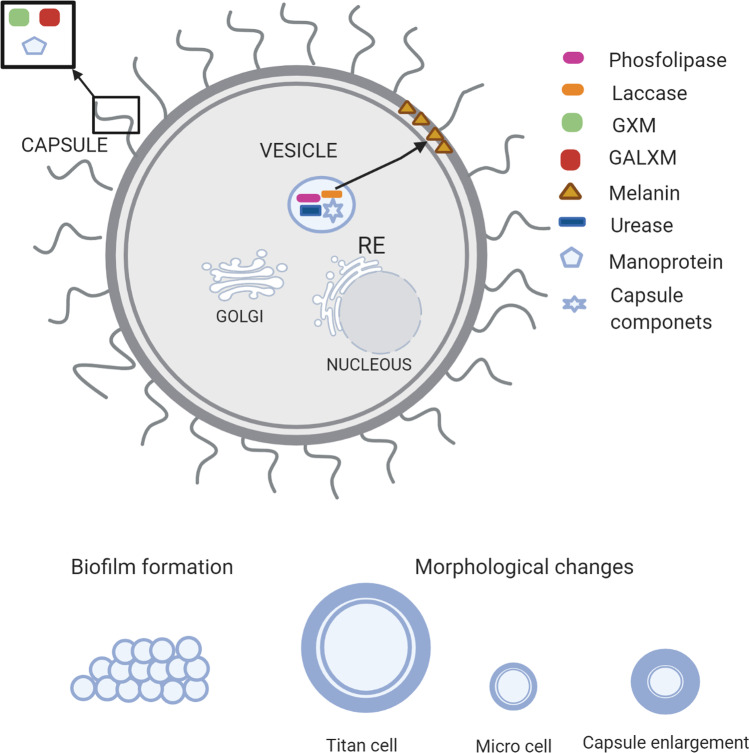

Cryptococcus spp. can rapidly and effectively adapt to varying conditions, favoring its survival in the environment and the infected host. Many virulence factors contribute to the pathobiology of this opportunistic intracellular pathogen, such as capsule, melanin formation, and the secretion of various enzymes [100]. The presence of a polysaccharide capsule around the cell wall produced both environmentally, and in infected hosts, represents a major virulence factor of Cryptococcus spp. [101]. Biochemical studies have shown that the capsule primarily comprises glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), representing ~ 88%. GXM is a polymer that consists mostly of a linear α-(1–3)-mannan substituted with β-(1–2)-glucopyranosyluronic acid and β-(1–4)-xylopyranosyl. Furthermore, it comprises 10% of galactoxylomannan (GalXM), also called glucuronoxylomannogalactan (GXMGal), and 2% mannoproteins. The GalXM consists of an α-(1 → 6)-galactan backbone with galactomannan side chains that are further substituted with variable numbers of xylose and glucuronic acid residues [102, 103].

Several studies have demonstrated that the capsular polysaccharides have immunomodulatory properties and improve fungal survival by aiding host immune evasion [50, 102–106]. The GXM is a strong inhibitor of phagocytosis and is immunomodulatory through the downregulation of inflammatory cytokines, depletion of complement components, and inhibition of monocyte antigen-presentation [107, 103, 106]. Other capsular components, such as the capsular lactonohydrolase (LHC1) of C. neoformans, involved in capsular tertiary structure, inhibit the deposition of components of the complement system. This inhibition prevents the destruction of the fungus by the formation of the membrane attack complex and fragments iC3b, which are important opsonins [105, 107]. Several CAP genes (CAP10, CAP59, CAP60, and CAP64) have been identified to encode capsule biosynthesis. Loss of any of the four genes was found to result in damage to the capsule and loss of virulence [108, 109].

The melanin-forming ability in the presence of diphenolic compounds plays a key role in the pathogenicity of Cryptococcus spp., which includes scavenging of free radical (antioxidant effect), thermo-tolerance (protection against heat and cold stress), metal ion sequestration, cell development, and mechanical-chemical cellular strength. These properties protect the yeast from a variety of environmental conditions and host effector mechanisms and also influence its susceptibility to antifungal agents [109, 110, 111]. In the presence of exogenous diphenolic compounds such as L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), C. neoformans produces brown-colored eumelanin via laccases (LAC1 and LAC2 genes) [112]. Once expressed, laccases are loaded into secretory vesicles and deposited as spherical particles within the cell wall using chitin as an anchoring molecule or are secreted extracellularly [112–116]. Systematic functional analyses of C. neoformans transcription factors (TFs) and kinases have revealed signaling components that are potentially involved in melanin production [117, 118]. Lee et al.[116] identified four melanin-regulating core TFs (BZP4, USV101, MBS1, and HOB1) required for the induction of the laccase gene (LAC1). Additionally, they found four potential kinases upstream of the core TFs and identified nine core kinases; their deletion led to defective melanin production and LAC1 induction. These four TFs may also play some roles in metal homeostasis, chitin synthesis and metabolism, and vesicle trafficking.

Many factors associated with C. neoforman’s pathogenesis must be transported from intracellular sites of synthesis to locations on the cell surface or outside of the plasma membrane. Such structures have been visualized as microvesicles, which contain many substances, including capsule precursors, melanin, and secreted enzymes [115]. These “virulence bags” are quite stable and contain enzymes, such as laccase, phospholipase, and urease, and their secretion is crucial for degrading host proteins [119, 109]. Laccase enzyme was required for not only biosynthesis of melanin but also prostaglandin E2; therefore, its activity was reported to be associated with enhanced fungal survival in macrophages [120]. Additionally, it plays an important role in the promotion of the extrapulmonary dissemination of C. neoformans to the brain [121]. Although the expression of LAC1 was uninvolved with the pulmonary clearance of low virulence strains, its expression was essential for the progressive growth of a highly virulent strain of C. neoformans in the lungs [121, 122]. Phospholipase B1 is a phospholipid-modifying enzyme that has been implicated in multiple stages of cryptococcal pathogenesis, including the initiation and persistence of pulmonary infection and dissemination to the central nervous system. Strains with mutations in the PLB1 gene were less able to survive in macrophages in cell culture and produced enlarged cells approaching the size of titan cells [123]. Urease is important for brain invasion because it contributes to the dissemination of fungal cells from the lung to the central nervous system (CNS), enhancing pathogen sequestration within the micro-capillary lining, thus facilitating blood–brain barrier crossing [109]. Importantly, a urease knockout strain (ure1) was less virulent, yielding a lower cryptococcal burden in the brain and reduced mortality rates of lethally infected mice [124]. Growth capacity at 37 ℃ is one of the important adaptations of C. neoformans. Although some cryptococcal species also have capsules, produce melanin, or both, those that can grow in vitro at 37 ℃ are rare and thus do not develop infections in humans [125, 126].

In addition, Cryptococcus spp. are able to produce biofilms [127]. These microbial communities adhered to biotic or abiotic surfaces and are surrounded by an extracellular matrix that can protect yeast from the antifungal drugs and host immune system [128, 129] and can affect medical devices [127, 130]. In vivo assay using G. mellonella as a model demonstrated that Cryptococcus spp. biofilm cells are more virulent than planktonic cells and highly express virulence genes such as LAC1, URE1, and CAP59 which are related to laccase, urease, and polysaccharide capsule, respectively [131].

The availability of iron is an important feature for C. neoformans and other pathogenic fungi since pathogenesis and virulence mechanisms are regulated and expressed in its presence [132]. In the host, the availability of iron is limited, and C. neoformans use instruments such as (1) reductive iron uptake, (2) siderophore synthesis and transport, and (3) use of heme and hemoglobin to obtain iron [132]. Reductive iron uptake involves the use of enzymes to reduce ferric iron to soluble ferrous iron; C. neoformans genes FRE1–7, FRE201, encoding putative ferric reductases have been identified, and the loss of these genes results in a reduction in the melanin production, increased susceptibility to azole antifungal drugs, and attenuation of virulence in mice model [133]. Reductive iron uptake has a second step, which involves the re-oxidation of ferrous iron to the ferric ion and the transport into the cells with the aid of permeases. For C. neoformans, the requirement of CFT1 (iron permease) for ferric iron uptake and acquisition of iron was demonstrated in vitro; moreover, mutants of this gene show reduced virulence in the murine model [134]. In addition, siderophore also contributes to iron acquisition in fungi, and C. neoformans do not produce siderophores and use exogenous siderophores (xenosiderophores) [132]. The gene Sit1 encodes a highly conserved transporter responsible for the uptake of xenosiderophores, which are important for C. neoformans survival in the environment, but not in virulence in the murine model [135]. C. neoformans use heme and hemoglobin as iron sources; however, mammals host the iron that is bound to heme in hemoglobin and other proteins (lactoferrin, transferrin, and others) [136]. The ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) complexes are involved in endocytosis or regulation of iron acquisition in the studies of Hu et al. [137, 138] which was demonstrated that Vps23 (a component of the ESCRT-I) has an important role in virulence in vivo in a mouse model and Vps22 (ESCRT-II) and Snf7/Vps20 (ESCRT-III) contribute to heme used for C. neoformans. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that several components of Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, a system required by eukaryotic cells to transport receptor-bound cargo from the cell surface, are essential for C. neoformans growth on heme and hemoglobin and for trafficking of these molecules [139].

In response to the host environment, morphological changes are required to survive and cause disease [140]. Specifically, C. neoformans alters its morphology and produces enlarged cells referred to as giant or “titan cells.” Titan cells generated in vitro harbor the main characteristics of titan cells produced in vivo (lungs of mice), including their large cell size (> 10 μm), polyploidy with a single nucleus, large vacuole with a peripheral nucleus, cellular organelles, dense capsule, and a thick cell wall [141]. The increased chitin in the titan cell wall results in a detrimental immune response that exacerbates disease [142]. These findings suggest a fundamental difference in titan and a typical surface structure that may contribute to reduced titan cell phagocytosis [141, 142, 143, 144]. In brief, titan cells’ virulence factors influence fungal interaction with host cells, including increased drug resistance, altered cell size, and reduced phagocytosis. C. neoformans is also described in microcell morphology (≤ 1 µm); different from titan cells, that can be found in the lungs, microcells have an important role in dissemination that can be found in the brain [145]. Evaluation of these virulence factors may lead to clearer insights into the involvement in fungal pathogenicity, the evasion of host immune responses, and the promotion of cryptococcal diseases. A summary of the virulence mechanism of Cryptococcus spp. is represented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of Cryptococcus spp. virulence factors. Designed using BioRender

Animal models

The emergence of Cryptococcus spp. infections, together with the necessity of understanding the pathogenicity of these and developing new treatment options, has led to the development of different animal models. Animal models complement in vitro assays and answer some hypotheses making it a useful tool in research. Several mammals are used as a model of experimental infection, for example, rats, mice, rabbits, and Guinea pigs. These vertebrate models have infections with clinical manifestations similar to human disease, contributing to the understanding of pathogenesis, of the immune system in the pathogen-host interaction, and mainly in the testing of new molecules with antifungal properties [146, 147].

In the last decade, studies with invertebrate models (Galleria mellonella, Acantamoeba castellanii, Dictyostelium discoideum, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster) have emerged, and some of these mini-host models have some advantages in experimental infection experiments when compared to mammals including a reduced maintenance cost, absence approval by the ethics committee, shorter reproduction times, large-scale studies, and mainly studies involving innate immunity, since invertebrates solely have the innate system [148–152 ]. Based on this, we will address some of the most used animal models for the study of cryptococcosis, comparing the advantages and their limitations.

The use of G. mellonella larvae as an experimental model in studies with Cryptococcus spp. has become quite popular, especially in the evaluation of pathogenesis and in the therapeutic approach of different antimicrobial compounds. Additionally, the immune response of this insect is similar to the innate immune response of mammals. Its main advantages are the ability of the larvae to live at the same body temperature as mammals and the ease of inoculation due to their large size compared to other invertebrate models such as D. melanogaster [131, 153–155].

In the study of Mylonakis et al. [153], the authors inoculated different strains of C. neoformans directly into the larvae hemolymph, and mortality was noted daily. C. neoformans was able to cause lethal infection in the model at both 30 and 37 ℃. The genes of C. neoformans (CAP59, GPA1, RAS1, and PKA1) involved in the virulence in mammals also played an important role in the infection of G. mellonella, showing a positive correlation between models. The use of antifungal therapy (amphotericin B plus flucytosine) administered before or after inoculation was effective to prolong survival and decrease the microbial load of C. neoformans in the larvae hemolymph. Moreover, morphological alteration as capsular enlargement and giant cells, described in mouse models, were also observed in G. mellonella infected by C. neoformans [144].

Another invertebrate model of great importance is the nematode C. elegans. Infection of nematodes by Cryptococcus spp. is by ingestion, so the usual laboratory food source (Escherichia coli auxotrophic strain) is replaced by the Cryptococcus spp. strain to be evaluated. Notably, in the case of ingestion of Cryptococcus spp. infection, it is not possible to provide an exact number of fungal cells within each nematode, which is a disadvantage when compared with G. mellonella where the standardized inoculum is injected directly into each larva [156]. C. elegans can be useful in studies of antifungal activity, synergistic effect, and virulence factors [157, 158]

The mouse (Mus musculus) is the most popular animal vertebrate model for studying infections using Cryptococcus spp. In this model, we have different routes of infection, such as intraperitoneal, intravenous, intranasal, intratracheal, and intracerebral [146, 147]. Additionally, the main reasons why this model is so widely used are its ease of handling, low maintenance cost when compared to other vertebrate models, and especially, the availability of different genetic strains, thus enabling refined studies in the field of immunology [146, 147].

Tissue culture in the murine model is still one of the most frequently used methods for studying fungal spread from the lungs to other organs, in which it is not always possible to detect and quantify the infection in the early stages. In this context, Costa et al. [159] provided a new method for studying cryptococcosis in a murine model using 99mTc-C. gattii. The authors radiolabeled one strain of C. gatti with technetium-99 m and used it to infect mice using intratracheal and intravenous routes for biodistribution assays. The isolation of C. gattii in the brain tissue, determined by the colony-forming unit, was observed only 24 h after infection of the animals. On the other hand, when the radioactivity count was used, the results showed the uptake of radioactivity in the brain tissue after 6 h for both routes of infection, suggesting fungal dissemination and indicating that 99mTc-C. gattii was able to cross the blood–brain barrier. Thus, the method developed by the authors can reduce the limitations of the commonly used methods (histopathology) and can improve the chances of obtaining crucial information about yeast virulence, host–pathogen interactions, or antifungal efficacy.

Yu et al. [172] investigated the anti-cryptococcal activity of Cbf-14 in vitro and in a pulmonary infection mouse model. Cbf-14 is a peptide derived from the cathelicidin family AMP that has proven to be potent against drug-resistant bacteria. Regarding the in vitro results, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay showed that Cbf-14 was effective against C. neoformans with a MIC value between 4 and 16 µg/mL, and the kinetics test indicated that Cbf-14 killed C. neoformans within 4–8 h in a concentration of 4 × MIC; this effect was better than miconazole. The mice infected and treated with Cbf-14 had an increased survival rate (up to 40%; 10 mg/kg/day) when compared with controls, and the Cbf-14 significantly inhibited the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, suggesting its anti-inflammatory potential.

Another vertebrate model widely used in experimental studies with Cryptococcus spp. is the rat (Rattus norvegicus). Compared to mice, the larger body size of rats is the main positive point that facilitates the performance of experimental surgical procedures, such as tissue collections, inoculations, bronchoalveolar lavage, and punctures [146]. The potential negative point is that the cost of breeding is higher than mice, a crucial point to be evaluated in long-term research [146, 147]. Krockenberger and colleagues [173] demonstrated a rat model infected by intratracheal inoculation in an excellent model of pulmonary cryptococcosis, mimicking natural infections in humans. The disease produced by C. gattii in rats is different from that caused by C. neoformans, and the infection with C. gattii led to progressive and fatal pneumonia, with late dissemination to the meninges; on the other hand, infection with the C. neoformans developed diffuse, subacute, self-limiting pneumonia, with early dissemination to the brain, spleen, and kidney.

As discussed in this topic, each animal model has unique characteristics with advantages and disadvantages. For example, mice have been extremely useful for studying the immune response to a pulmonary infection, since the use of the invertebrate model of G. mellonella in screening studies with a greater number of fungal strains. Therefore, the choice of an animal model will depend on the objective of the study and the resources available. In vivo invertebrate models such as G. mellonella and C. elegans are used by Brazilian research groups to study virulence, clinical isolates characterization and new treatments (toxicity and efficacy), and vertebrate models as mice are used to validate the results as demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

In vivo study of C. neoformans in different fields

| Amimal model | Objective | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| G. mellonella | Comparation of planktonic and biofilms Cryptococcus spp. cells | [131] |

| Impact of resistance to fluconazole on virulence and morphology | [160] | |

| Antifungal activity of 3′-hydroxychalcone against C. gattii | [161] | |

| Participation of Zip3 in virulence of C. gattii | [162] | |

| Efficacy of voriconazole treatment for cryptococcosis | [163] | |

| G. mellonella and mice | Synergistic treatment amphotericin B and pedalitin for biofilms C. neoformans infection | [164] |

| Antifungal action of a new phenylthiazole cryptococcosis treatment | [165] | |

| Mice | Role of Toll-like receptor 9 in C. gattii infection | [166] |

| Effect of cumarin in combination with fluconazole | [167] | |

| Influence of microbiota on C. gattii infection | [168] | |

| Effect of a non-azole agrochemical on the antifungal susceptibility and virulence | [169] | |

| Rat | Microdialysis model to access free levels of voriconazole in rat the brains | [170] |

| Proteomics of rat lungs infected by C. gattii to understand molecular pathogenesis | [171] |

Conclusion

In summary, this review demonstrates that Brazilian data on the real incidence of cryptococcosis are scarce. HIV patients and solid transplantation are important population risk factors; however, infections in immunocompetent individuals are described. In addition, C. neoformans VNI and C. gattii VGII are the most prevalent genotypes. Regarding cryptococcosis treatment, despite the recommendations for the use of flucytosine, this compound is not available in Brazil. The introduction of cryptococcosis as a compulsory notification disease offers promising future perspectives about data on real incidence and antifungal resistance and would help the management of these infections.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Trilles L, Lazera Mdos S, Wanke B, Oliveira RV, Barbosa GG, Nishikawa MM, et al. Regional pattern of the molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(5):455–462. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762008000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(8):873–881. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Júnior JL LV, Júnior P, Nicola AM, Santos M (2017) Implementation of the Brazil Cryptococcosis network in the federal district - RCB-DF. J Med Health Brasília 6(2):151–3:2238–5339

- 4.Leimann BC, Koifman RJ. Cryptococcal meningitis in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, 1994–2004. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(11):2582–2592. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008001100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser JA, Giles SS, Wenink EC, Geunes-Boyer SG, Wright JR, Diezmann S, et al. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1360–1364. doi: 10.1038/nature04220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.May RC, Stone NR, Wiesner DL, Bicanic T, Nielsen K. Cryptococcus: from environmental saprophyte to global pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(2):106–117. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes J, Desjardins CA, Sykes SM, Beale MA, Vanhove M, Sakthikumar S, et al. Tracing genetic exchange and biogeography of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii at the global population level. Genetics. 2017;207(1):327–346. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.203836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bielska E, May RC. What makes Cryptococcus gattii a pathogen? FEMS Yeast Res. 2016;16(1):fov106. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/fov106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alanio A, Vernel-Pauillac F, Sturny-Leclere A, Dromer F (2015) Cryptococcus neoformans host adaptation: toward biological evidence of dormancy. mBio 6(2). 10.1128/mBio.02580-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Saha DC, Goldman DL, Shao X, Casadevall A, Husain S, Limaye AP, et al. Serologic evidence for reactivation of cryptococcosis in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(12):1550–1554. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00242-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunes JO, Tsujisaki RAS, Nunes MO, Lima GME, Paniago AMM, Pontes E, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis epidemiology: 17 years of experience in a State of the Brazilian Pantanal. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018;51(4):485–492. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0050-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngamskulrungroj P, Gilgado F, Faganello J, Litvintseva AP, Leal AL, Tsui KM, et al. Genetic diversity of the Cryptococcus species complex suggests that Cryptococcus gattii deserves to have varieties. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litvintseva AP, Thakur R, Vilgalys R, Mitchell TG. Multilocus sequence typing reveals three genetic subpopulations of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (serotype A), including a unique population in Botswana. Genetics. 2006;172(4):2223–2238. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cogliati M. Global molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii: an atlas of the molecular types. Scientifica (Cairo) 2013;2013:675213. doi: 10.1155/2013/675213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagen F, Lumbsch HT, Arsic Arsenijevic V, Badali H, Bertout S, Billmyre RB et al (2017) Importance of resolving fungal nomenclature: the case of multiple pathogenic species in the Cryptococcus genus. mSphere 2(4). 10.1128/mSphere.00238-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kwon-Chung KJ, Varma A. Do major species concepts support one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6(4):574–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abegg MA, Cella FL, Faganello J, Valente P, Schrank A, Vainstein MH. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolated from the excreta of psittaciformes in a southern Brazilian zoological garden. Mycopathologia. 2006;161(2):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s11046-005-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamari A, Sepahvand A, Mohammadi R. Isolation and molecular characterization of Cryptococcus species isolated from pigeon nests and Eucalyptus trees. Curr Med Mycol. 2017;3(2):20–25. doi: 10.29252/cmm.3.2.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cogliati M, D'Amicis R, Zani A, Montagna MT, Caggiano G, De Giglio O et al (2016) Environmental distribution of Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii around the Mediterranean basin. FEMS Yeast Res 16(4). 10.1093/femsyr/fow045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Anzai MC, Lazera Mdos S, Wanke B, Trilles L, Dutra V, de Paula DA, et al. Cryptococcus gattii VGII in a Plathymenia reticulata hollow in Cuiaba, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mycoses. 2014;57(7):414–418. doi: 10.1111/myc.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khayhan K, Hagen F, Norkaew T, Puengchan T, Boekhout T, Sriburee P. Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii from a Castanopsis argyrophylla tree hollow (Mai-Kaw), Chiang Mai, Thailand. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(3–4):365–370. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trilles L, Lazera M, Wanke B, Theelen B, Boekhout T. Genetic characterization of environmental isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex from Brazil. Med Mycol. 2003;41(5):383–390. doi: 10.1080/1369378031000137206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazera MS, Cavalcanti MA, Trilles L, Nishikawa MM, Wanke B. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii–evidence for a natural habitat related to decaying wood in a pottery tree hollow. Med Mycol. 1998;36(2):119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazera MS, Salmito Cavalcanti MA, Londero AT, Trilles L, Nishikawa MM, Wanke B. Possible primary ecological niche of Cryptococcus neoformans. Med Mycol. 2000;38(5):379–383. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.5.379.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alves GS, Freire AK, BentesAdos S, Pinheiro JF, de Souza JV, Wanke B, et al. Molecular typing of environmental Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex isolates from Manaus, Amazonas, Beazil. Mycoses. 2016;59(8):509–515. doi: 10.1111/myc.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filiu WF, Wanke B, Aguena SM, Vilela VO, Macedo RC, Lazera M. Avian habitats as sources of Cryptococcus neoformans in the city of Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35(6):591–595. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822002000600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa Sdo P, Lazera Mdos S, Santos WR, Morales BP, Bezerra CC, Nishikawa MM, et al. First isolation of Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGII and Cryptococcus neoformans molecular type VNI from environmental sources in the city of Belem, Para, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(4):662–664. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000400023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montenegro H, Paula CR. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. neoformans in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Med Mycol. 2000;38(5):385–390. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.5.385.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brito-Santos F, Barbosa GG, Trilles L, Nishikawa MM, Wanke B, Meyer W, et al. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii VGII from indoor dust from typical wooden houses in the deep Amazonas of the Rio Negro basin. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0115866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrade-Silva LE, Ferreira-Paim K, Ferreira TB, Vilas-Boas A, Mora DJ, Manzato VM, et al. Genotypic analysis of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from Brazil reveals the presence of VNB isolates and a correlation with biological factors. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spina-Tensini T, Muro MD, Queiroz-Telles F, Strozzi I, Moraes ST, Petterle RR, et al. Geographic distribution of patients affected by Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complexes meningitis, pigeon and tree populations in Southern Brazil. Mycoses. 2017;60(1):51–58. doi: 10.1111/myc.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montoya MC, Magwene PM, Perfect JR (2021) Associations between Cryptococcus genotypes, phenotypes, and clinical parameters of human disease: a review. J Fungi (Basel) 7(4). 10.3390/jof7040260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Aguiar P, Pedroso RDS, Borges AS, Moreira TA, Araujo LB, Roder D. The epidemiology of cryptococcosis and the characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated in a Brazilian University Hospital. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2017;59:e13. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946201759013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Favalessa OC, Lazera Mdos S, Wanke B, Trilles L, Takahara DT, Tadano T, et al. Fatal Cryptococcus gattii genotype AFLP6/VGII infection in a HIV-negative patient: case report and a literature review. Mycoses. 2014;57(10):639–643. doi: 10.1111/myc.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Figueiredo TP, Lucas RC, Cazzaniga RA, Franca CN, Segato F, Taglialegna R, et al. Antifungal susceptibility testing and genotyping characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans and gattii isolates from hiv-infected patients of Ribeirao Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2016;58:69. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946201658069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firacative C, Lizarazo J, Illnait-Zaragozi MT, Castaneda E, Latin American Cryptococcal Study G The status of cryptococcosis in Latin America. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2018;113(7):e170554. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760170554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freire AK, dos Santos BA, de Lima SI, Matsuura AB, Ogusku MM, Salem JI, et al. Molecular characterisation of the causative agents of Cryptococcosis in patients of a tertiary healthcare facility in the state of Amazonas-Brazil. Mycoses. 2012;55(3):e145–e150. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herkert PF, Meis JF, Lucca Oliveira de Salvador G, Rodrigues Gomes R, Aparecida Vicente V, Dominguez Muro M, et al. Molecular characterization and antifungal susceptibility testing of Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto from southern Brazil. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67(4):560–569. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Igreja RP, Lazera Mdos S, Wanke B, Galhardo MC, Kidd SE, Meyer W. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from AIDS patients of the Brazilian city, Rio de Janeiro. Med Mycol. 2004;42(3):229–238. doi: 10.1080/13693780310001644743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Da Silva BK, Freire AK, Bentes Ados S, Sampaio Ide L, Santos LO, Dos Santos MS, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex from the Amazonas State in Brazil. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2012;29(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martins LM, Wanke B, Lazera Mdos S, Trilles L, Barbosa GG, Macedo RC, et al. Genotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii as agents of endemic cryptococcosis in Teresina, Piaui (northeastern Brazil) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(6):725–730. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matos CS, de Souza Andrade A, Oliveira NS, Barros TF. Microbiological characteristics of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus spp. in Bahia, Brazil: molecular types and antifungal susceptibilities. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(7):1647–1652. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1488-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumoto MT, Fusco-Almeida AM, Baeza LC, Melhem Mde S, Medes-Giannini MJ. Genotyping, serotyping and determination of mating-type of Cryptococcus neoformans clinical isolates from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49(1):41–47. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652007000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mora DJ, Pedrosa AL, Rodrigues V, Leite Maffei CM, Trilles L, Dos Santos LM, et al. Genotype and mating type distribution within clinical Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolates from patients with cryptococcal meningitis in Uberaba, Minas Gerais. Brazil Med Mycol. 2010;48(4):561–569. doi: 10.3109/13693780903358317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ponzio V, Chen Y, Rodrigues AM, Tenor JL, Toffaletti DL, Medina-Pestana JO, et al. Genotypic diversity and clinical outcome of cryptococcosis in renal transplant recipients in Brazil. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):119–129. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2018.1562849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santos WR, Meyer W, Wanke B, Costa SP, Trilles L, Nascimento JL, et al. Primary endemic Cryptococcosis gattii by molecular type VGII in the state of Para, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(8):813–818. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762008000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsujisaki RA, Paniago AM, Lima Junior MS, Alencar Dde S, Spositto FL, Nunes Mde O, et al. First molecular typing of cryptococcemia-causing cryptococcus in central-west Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2013;176(3–4):267–272. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Souto AC, Bonfietti LX, Ferreira-Paim K, Trilles L, Martins M, Ribeiro-Alves M, et al. Population genetic analysis reveals a high genetic diversity in the Brazilian Cryptococcus gattii VGII population and shifts the global origin from the Amazon rainforest to the semi-arid desert in the Northeast of Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(8):e0004885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vilas-Boas AM, Andrade-Silva LE, Ferreira-Paim K, Mora DJ, Ferreira TB, Santos DA, et al. High genetic variability of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus gattii isolates from Brazil. Med Mycol. 2020;58(8):1126–1137. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myaa019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villena SN, Pinheiro RO, Pinheiro CS, Nunes MP, Takiya CM, DosReis GA, et al. Capsular polysaccharides galactoxylomannan and glucuronoxylomannan from Cryptococcus neoformans induce macrophage apoptosis mediated by Fas ligand. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10(6):1274–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wirth F, Azevedo MI, Goldani LZ. Molecular types of Cryptococcus species isolated from patients with cryptococcal meningitis in a Brazilian tertiary care hospital. Braz J Infect Dis. 2018;22(6):495–498. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grizante Bariao PH, Tonani L, Cocio TA, Martinez R, Nascimento E, von Zeska Kress MR. Molecular typing, in vitro susceptibility and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complex clinical isolates from south-eastern Brazil. Mycoses. 2020;63(12):1341–1351. doi: 10.1111/myc.13174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Souza LK, Souza Junior AH, Costa CR, Faganello J, Vainstein MH, Chagas AL, et al. Molecular typing and antifungal susceptibility of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans species complex isolates in Goiania, Brazil. Mycoses. 2010;53(1):62–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boekhout T, Theelen B, Diaz M, Fell JW, Hop WCJ, Abeln ECA, et al. Hybrid genotypes in the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology (Reading) 2001;147(Pt 4):891–907. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meyer W, Castaneda A, Jackson S, Huynh M, Castaneda E, IberoAmericanCryptococcal Study G Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(2):189–195. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medeiros Ribeiro A, Silva LK, SilveiraSchrank I, Schrank A, Meyer W, Henning Vainstein M. Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans serotype D from Eucalypts in South Brazil. Med Mycol. 2006;44(8):707–713. doi: 10.1080/13693780600917209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hurtado JC, Castillo P, Fernandes F, Navarro M, Lovane L, Casas I, et al. Mortality due to Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in low-income settings: an autopsy study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7493. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43941-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colombo TE, Soares MM, D'Avilla SC, Nogueira MC, de Almeida MT. Identification of fungal diseases at necropsy. Pathol Res Pract. 2012;208(9):549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torres RG, Etchebehere RM, Adad SJ, Micheletti AR, Ribeiro BM, Silva LE, et al. Cryptococcosis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients clinically confirmed and/or diagnosed at necropsy in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(4):781–785. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Azambuja AZ, Wissmann Neto G, Watte G, Antoniolli L, Goldani LZ. Cryptococcal meningitis: a retrospective cohort of a Brazilian reference hospital in the post-HAART era of universal access. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:6512468. doi: 10.1155/2018/6512468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vechi HT, Theodoro RC, de Oliveira AL, Gomes R, Soares RDA, Freire MG, et al. Invasive fungal infection by Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii with bone marrow and meningeal involvement in a HIV-infected patient: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3831-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Oliveira L, Martins Mdos A, Vidal JE, Szeszs MW, Pappalardo MC, Melhem MS. Report of filamentous forms in a mating type VNI clinical sequential isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from an HIV virus-infected patient. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2015;7:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Carvalho SR, Schiave LA, Dos Santos Quaglio AS, de Gaitani CM, Martinez R. Fluconazole non-susceptible Cryptococcus neoformans, relapsing/refractory Cryptococcosis and long-term use of liposomal amphotericin B in an AIDS patient. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(9–10):855–861. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):291–322. doi: 10.1086/649858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hamerschlak N, Pasternak J, Wagner J, Perini GF. Not all that shines is cancer: pulmonary cryptococcosis mimicking lymphoma in [(18)] F fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2012;10(4):502–504. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082012000400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amaral DM, Rocha RC, Carneiro LE, Vasconcelos DM, Abreu MA. Disseminated cryptococcosis manifested as a single tumor in an immunocompetent patient, similar to the cutaneous primary forms. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):29–31. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moretti de Lima A, Rodrigues MM, Santiago Reis CM. Cutaneous Cryptococcosis mimicking leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(1):3–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dias Lopes MR, Roper GB, Dias Lopes FA, Moreira Neto LJ, Svidzinski TIE, Grava S. Mediastinal cryptococcosis simulating thyroid neoplasia in immunocompetent patient with prior diagnosis and treatment for COPD. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2019;24:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neves RP, Lima Neto RG, Leite MC, Silva VK, Santos Fde A, Macedo DP. Cryptococcus laurentii fungaemia in a cervical cancer patient. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19(6):660–663. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pappas PG. Cryptococcal infections in non-HIV-infected patients. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2013;124:61–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lomes NR, Melhem MS, Szeszs MW, Martins Mdos A, Buccheri R. Cryptococcosis in non-HIV/non-transplant patients: a Brazilian case series. Med Mycol. 2016;54(7):669–676. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barbosa De Araujo Neto F, Corona De Godoy Bueno C, Tambelini Gomes L, Alejandra Ortiz Navas D, Wanderley M, Gallotti Borges Carneiro S, et al. The diagnostic challenge of an infrequent spectrum of Cryptococcus infection. Case Rep Radiol. 2019;2019:5970648. doi: 10.1155/2019/5970648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haddad N, Cavallaro MC, Lopes MP, Fernandez JM, Laborda LS, Otoch JP, et al. Pulmonary cryptococcoma: a rare and challenging diagnosis in immunocompetent patients. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(2):35–40. doi: 10.4322/acr.2015.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oliveira Fde M, Severo CB, Guazzelli LS, Severo LC. Cryptococcus gattii fungemia: report of a case with lung and brain lesions mimicking radiological features of malignancy. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49(4):263–265. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652007000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cavalcante-Filho JRM, Alves-Filho FWP, Araujo GB, Braga-Neto P, Ribeiro EML. Kinsbourne syndrome associated with cryptococcosis infection. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;47:86–87. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pedroso JL, Barsottini OG. Acute parkinsonism in Cryptococcus gattii meningoencephalitis: extensive lesions in basal ganglia. Mov Disord. 2012;27(11):1372. doi: 10.1002/mds.25074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, Enokihara M, Porro AM. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 Suppl 1):69–72. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dora JM, Kelbert S, Deutschendorf C, Cunha VS, Aquino VR, Santos RP, et al. Cutaneous cryptococccosis due to Cryptococcus gattii in immunocompetent hosts: case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2006;161(4):235–238. doi: 10.1007/s11046-006-0277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marques SA, Bastazini I, Jr, Martins AL, Barreto JA, Barbieri D'Elia MP, Lastoria JC, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in Brazil: report of 11 cases in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(7):780–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Corrêa MdPSC, Oliveira EC, Duarte RRBS, Pardal PPO, Oliveira FdM, Severo LC (1999) Criptococose em crianças no Estado do Pará, Brasil. J Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 32:505–8 [PubMed]

- 81.Soares BM, Santos DA, Kohler LM, da Costa CG, de Carvalho IR, dos Anjos MM, et al. Cerebral infection caused by Cryptococcus gattii: a case report and antifungal susceptibility testing. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2008;25(4):242–245. doi: 10.1016/S1130-1406(08)70057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(4):980–1024. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00126-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fernandes KE, Brockway A, Haverkamp M, Cuomo CA, van Ogtrop F, Perfect JR et al (2018) Phenotypic variability correlates with clinical outcome in cryptococcus isolates obtained from Botswanan HIV/AIDS patients. mBio 9(5). 10.1128/mBio.02016-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Beale MA, Sabiiti W, Robertson EJ, Fuentes-Cabrejo KM, O'Hanlon SJ, Jarvis JN, et al. Genotypic diversity is associated with clinical outcome and phenotype in cryptococcal meningitis across Southern Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(6):e0003847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Espinel-Ingroff A, Aller AI, Canton E, Castañón-Olivares LR, Chowdhary A, Cordoba S, et al. Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex: an international study of wild-type susceptibility endpoint distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(11):5898–5906. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01115-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beardsley J, Sorrell TC, Chen SC (2019) Central nervous system cryptococcal infections in non-HIV infected patients. J Fungi (Basel) 5(3). 10.3390/jof5030071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Moretti ML, Resende MR, Lazera MS, Colombo AL, Shikanai-Yasuda MA. Guidelines in cryptococcosis–2008. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41(5):524–544. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cowen LE. The evolution of fungal drug resistance: modulating the trajectory from genotype to phenotype. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(3):187–198. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ministério da Saúde Brasil (2018). Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Manejo da Infecção pelo HIV em Crianças e Adolescentes Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2018

- 90.Molloy SF, Kanyama C, Heyderman RS, Loyse A, Kouanfack C, Chanda D et al (2018) Antifungal combinations for treatment of Cryptococcal meningitis in Africa. 378(11):1004–17. 10.1056/NEJMoa1710922 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.WHO (2018). Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of Cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents and children: supplement to the 2016 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 [PubMed]