Abstract

Personality traits are important factors in determining online behaviors. Especially personality traits are linked with users’ behavior on Facebook. Despite the substantial quantity of studies conducted on the relationship between personality factors and Facebook addiction, researchers have yet to reach an agreement. This study sought to examine the relationship between personality traits and Facebook addiction. In this meta-analysis study, agreeableness, openness to experience and conscientiousness were negatively related to Facebook addiction. Loneliness, narcissism, impulsivity and shyness were significantly correlated with Facebook addiction. Meta analysis also found that geographical location, personality scales, Facebook addiction scales, publication status moderated the link between personality variables and Facebook addiction. The limitations and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: Big five personality traits, Loneliness, Narcissism, Shyness, Impulsivity, Facebook addiction

Big five personality traits; Loneliness; Narcissism; Shyness; Impulsivity; Facebook addiction.

1. Introduction

Facebook started as a social networking space for providing better communication services in connecting and creating global networks. Facebook provides a platform where users can build social relations, follow what others are doing, share personal information through pictures, have conversation with others through messages and speak up their opinions (Boyd and Ellison, 2007). Using Facebook in a sober way can produce positive experiences like maintaining personal relationships with friends and family, passing time and getting entertained by playing games and chatting with friends. Some people build appealing online self-identity and present themselves to other users in an attractive way which satisfies the need for popularity. Some people engage in self-promoting activities which can enhance their self-esteem and it can be self-affirming and reassuring (Ryan et al., 2014; Caers et al., 2013).

The usage of Facebook could also become a compulsive habit as users tend to check their newsfeeds and notifications. The compulsiveness may become intensive and excessive which is assumed as Facebook addiction or dependency or intrusion. However, its excessive usage can be debilitating for some of its users (Erevik et al., 2018).

Montag et al. (2019) listed out possible reasons which can explain the addiction to social media. Individuals engage in endless or continuous scrolling because it is facilitated by rewards and built-in features such as “auto play” and “news feed” which hook users by distorting sense of time. Mere exposure effect says that the more individual is exposed to something the more they like it, which is happening with respect to social media. Social comparison in social media is also an important factor where users compare themselves with other users in terms of how many likes and comments they received.

The biological hypothesis states that individuals who are likely to be addicted tend to have a fewer neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin (Beard, 2005; Macït et al., 2018). Serotonin is accountable for regulating moods while dopamine correlates with arousal, rewarding and motivating experiences (Arias-Carrión and Pöppel, 2007). When individuals get likes and comments for their posts it may trigger these neurotransmitters and its results in their high secretion (Horn, 2012). Apart from this biological utility, these features of Facebook might also satisfy interpersonal needs (Yen et al., 2009).

1.1. Defining facebook addiction

Since there is no agreement with regard to the formulation of Facebook addiction, it is addressed using different connotations like Facebook addiction (Andreassen et al., 2012), problematic Facebook use (Marino et al., 2016a, b), and Facebook intrusion (Elphinston and Noller, 2011).

Montag et al. (2015) suggested that social media addiction shall be conceptualized as a sub dimension of internet addiction, which can be viewed as an umbrella construct. Because, users perform a plethora of activities by using internet, in which social media engagement is one of the concerns. Blachnio and Przeiorka (2016) also affirmed this notion that addiction to social media sites should be regarded as a subtype of internet addiction. On the other hand, internet addiction is interpreted as an empty concept in the sense that addiction does not refer to internet but available content and application in internet medium (Chou et al., 2005; Widyanto and Griffiths, 2006).

While the others, Kuss & Billieux (2016), Andreassen et al. (2016); Starcevic & Billieux (2017) advised to investigate the specific intricacies to distinguish and differentiate between internet addiction and SNS addiction. All this said and done, internet and SNS addiction are not yet recognised and validated as specific nosological disorders (Pies, 2009).

But there is an agreement when it comes to how the heavy usage of Facebook is consequential and detrimental. It can badly interfere with work life, academic activities, and interpersonal relationships (Marino et al., 2018; Poli, 2017). To this effect some studies found that it can cause poor wellbeing, poor cognitive functioning, low self-esteem (Oldmeadow et al., 2013; Eşkisu et al., 2017; Perrone, 2016).

The term social media addiction may not be a helpful construct, as it presents a homogenised and generic view which fails to grasp the various types of users engaging in different social media platforms. This makes sense when we recognise that some social media networks are more popular than others because of the attractive capacity of their features which pull users to engage in sustained usage. Even though addiction to social media and addiction to Facebook denote to the same mechanisms which enable the addictive usage but when we carry out specific investigation regarding Facebook addiction it allows us to identify its proportion in contributing to individuals’ poor well-being. Accordingly, this helps in designing better therapies and interventions to deal with the harmful consequences of Facebook addiction (Sheldon et al., 2021).

The conceptual distinction between over engagement, abuse, and addiction is vague; nonetheless, Facebook addiction was defined by simulating conceptual similarities from components model of addiction. According to Griffiths (2005) & Andreassen et al. (2014), social media addiction is "heightened apprehension about social media, experiencing an overpowering drive to log on to or use social media, and spending so much time and effort on social media that it has a detrimental influence on other key life areas of life". Balcerowska et al. (2020) argue that categories such as addiction to social media addiction and Facebook talk about the similar underlying addictive process to social networking sites with varying manifestations which demarcate level of addiction, stage of addiction or subtype of addiction. Regardless, Facebook addiction and other addictions to particular social media could nevertheless be beneficial constructs, as they can delineate the contribution of social media usage to the individuals’ deteriorated well-being. In this view, Kuss and Griffiths (2011) suggested the plausibility of “Facebook Addiction Disorder” since the addiction criteria, such as disregard to personal life, psychological fixation, escapism, mood altering experiences, tolerance, and keeping addictive behaviour in disguise, seem to be present in some people who use Facebook excessively. Accordingly, the various components of Facebook addiction are: salience (obsession about usage), mood bolstering (to change negative moods), tolerance (escalated usage), withdrawal symptoms (undergoing unpleasant emotions when unable to use it), conflict (preferring usage over other activities and relationships) and relapse (unsuccessful in stopping usage) (Griffiths, 2005).

1.2. Ill effects of facebook addiction on mental health

Excessive Facebook use can jeopardize the individual as it is likely to develop into an addiction (Brailovskaia et al., 2019), which has a debilitating effect on social and interpersonal relationships, academics, employment, and psychological health and well-being" (Andreassen and Pallesen 2014). Xu and Tan (2012) suggested that the trajectory from normal to problematic and addictive use arises when it is perceived as an effective (or even exclusive) way to relieve from stressful experiences, feeling lonely, or depressive episodes. Consequently, Facebook addiction is having positive correlation with depression (Błachnio et al., 2015; Appel et al., 2016), anxiety symptoms (Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2017), lowered wellbeing (Satici and Uysal., 2015; Uysal et al., 2013) poor sleep quality (Wolniczak et al., 2013), impaired self-reported work performance (Andreassen et al., 2014) and poor academic achievement (Kirschner and Karpinski, 2010).

1.3. Significance of investigating the role of personality traits

The approach to enquire how personality traits relate with various phenomenon has produced good outcomes. Young and Rodgers (1998) had investigated the relationship between personality traits and internet addiction and found that individuals who met the criteria for internet addiction were mostly introverted, involve in limited social gatherings, unconventional and emotionally sensitive.

Amichai-Hamburger (2002) described that ‘‘personality is an important aspect in determining internet behaviours and activities’’. Also, Dalvi-Esfahani et al. (2019) found that personality traits are the major determinants in increasing the likelihood of developing addiction to social media. If individuals with diverse personality traits are drawn to the use of social media that operates through social rewards and processes of use and gratification, then those personality traits are vulnerable to social media addiction. In other words, Personality as a prominent factor which has been implicated in the onset, growth and perpetuation of addictive behaviours (Andreassen et al., 2013; Grant et al., 2010).

Likewise, content on Facebook is customised according to individual preferences. So, the user experience differs across individuals which creates diverse usage patterns. A better understanding of Facebook effects can be gained by studying how individuals are taking the advantage of the varied uses and features being offered by Facebook. Examining nuanced individual differences is of utmost concern, and it can identify individuals who are most affected by Facebook (Orben, 2019, 2020).

1.4. Literature review

1.4.1. Personality and facebook addiction

Big five personality framework is one of the robust models in explaining the structure of personality. It consists of extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness to experience, neuroticism. Extraversion trait indicates being social, outgoing; agreeableness is defined as helpful, altruistic, and considerate; conscientiousness is characterised by focus on achieving goals, being productive; neuroticism is viewed as being vulnerable to mood changes, experience negative emotions and openness to experience signifies the interest to experience new ventures, being creative and imaginative (Fiske, 1949; McCrae and Costa, 1999).

Earlier research has studied the connection between Big five personality characteristics and Facebook usage (Ryan and Xenos, 2011). Conscientiousness, extraversion and emotional stability negatively related to Facebook addiction (Błachnio et al., 2017). Extraversion is positively linked and conscientiousness and openness to experience were negatively linked to Facebook addiction (Kanat-Maymon et al., 2018); Atroszko et al. (2018); Balcerowska et al. (2020); Caci et al. (2017); Tesi (2018); Schyff et al. (2020); Biolcati et al. (2018). Rosales, Guajardo & Medrano (2021) found that only neuroticism among the big five personality traits was significantly correlated with Facebook addiction. Horzum et al..(2021) found that conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness to experience have significantly predicted Facebook addiction whereas extraversion and neuroticism did not. In their study, Sheldon et al. (2021) found that none of the big five traits displayed significant relationship with Facebook addiction. Miceli, Cardaci, Scrima & Caci (2021) found that neuroticism moderated the link between past negative time perception and Facebook addiction. Sindermann et al. (2020b) found that extraversion and neuroticism were positively related to the Facebook use disorder and conscientiousness was negatively related to Facebook use disorder. In another study conducted by Sindermann et al. (2020a) found that conscientiousness was negatively correlated and neuroticism was positively correlated with Facebook use disorder.

Besides the Big Five Factors, other personality traits have consistently been linked to Facebook addiction such as Narcissism, loneliness, shyness and impulsivity.

Impulsivity ‘‘is a tendency to react quickly and unpredictably to internal or external stimuli, regardless of the repercussions for the oneself or others” (Moeller et al., 2001). Facebook addicted individuals are prone to impulsive decision making (Delaney et al., 2018). Impulsivity seems to be playing major role in Facebook addiction also (Fowler et al., 2020). The built-in elements of Facebook might drive the link between impulsivity and time spend on it (Sindermann, Elhai and Montag, 2020b). Cudo et al. (2020) & Rothen et al. (2018), found that impulsivity predicted Facebook addiction. Highly impulsive individuals engage in intensive use of Facebook which may lead to dysfunctional compared to low impulsive individuals. Cudo et al. (2020) tried to look into the relationship between sub dimensions of impulsivity and problematic Facebook use and found that high attentional impulsivity is positively related to problematic Facebook usage. In light of this evidence researchers interpreted that difficulty in focusing on tasks may lead to problematic Facebook usage. Fowler et al. (2020) proved that rash impulsiveness component of impulsivity is strongly related to the Facebook addiction than other components of impulsivity. Tutal et al. (2021) also argued that maladaptive coping methods such as emotion centered coping is mediating the relationship among impulsivity and Facebook addiction.

Lonely individuals tend to lack self-presentation skills, to compensate this they may prefer online interactions. Loneliness is the plight of unintentional social detachment or the awareness of being lonesome (Russell, 2009). Lonely persons frequently use online social communication to escape their negative emotions (Caplan, 2005). Lonely individuals are more vulnerable to Facebook addictive tendencies (Błachnio et al., 2016; Shettar et al., 2017). Social compensation theory proposed that loneliness could be the prominent contributing variable to Facebook addiction. Various researchers also found empirical evidence for this. Blachnio and Przepiorka (2018) found that loneliness predicted problematic Facebook use and problematic Facebook use predicted loneliness. This finding invited the discussion about its bidirectional nature as to whether loneliness causes Facebook addiction or Facebook addiction causes loneliness (Çapan and Sarıçalı, 2016). But it went unanswered due to the lacuna of longitudinal studies. Aung and Tin (2020) found a significant positive correlation between Facebook addiction and loneliness and Iranmanesh et al. (2021) also found that Facebook addiction is exacerbated by loneliness. Satici (2019) claimed that shyness and loneliness mediated the relationship between Facebook addiction and subjective wellbeing. Uram and Skalski (2020) found that loneliness coupled with other factors such as low life satisfaction and low self-esteem and FOMO has led to strong Facebook addiction. Ho (2021) reported that loneliness moderated the relationship between Facebook addiction and depression.

With regard to narcissism, researchers expressed higher amount of consensus that it is having positive correlation with Facebook addiction. In a recent study by Rahim et al. (2020) reported that high narcissistic individuals are prone to Facebook addiction. A study conducted in Germany by Brailovskaia et al. (2018) found that narcissism was positively associated with Facebook addiction disorder. Brailovskaia, Margraf, Köllner (2019) studied inpatient sample and found that high levels of narcissism can act as risk factor for Facebook addiction particularly if they are suffering from other mental health disorders. Brailovskaia et al. (2020) studied the influence of various mediating factors and reported that narcissism was positively related to Facebook addiction. The relation between narcissism and Facebook addiction disorder was mediated by Facebook flow. Brailovskaia et al. (2020) studied the how the different types of narcissism related to Facebook addiction and found that grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were positively associated with Facebook addiction. Casale and Fioravanti (2018) found that grandiose narcissism was related to Facebook addiction rather than vulnerable narcissism. Balcerowska et al. (2020), found that only specific dimensions of narcissism were related to Facebook. Admiration demand significantly predicted Facebook addiction but vanity and leadership dimension did not predict Facebook addiction. Finally, Brailovskaia and Margraf (2017), in their longitudinal study, found that Facebook addiction disorder was significantly associated with narcissism.

Shyness is defined as "negative evaluation of the self, which creates inhibition in social situations and interferes with realizing one's personal or professional goals" (Henderson et al., 2001). Shy people prefer online conversations (Ebeling-Witte et al., 2007) accordingly, spend more time on Facebook, display favourable attitudes towards Facebook and consider it as an appealing method of communication (Orr et al., 2009) and often interact with Facebook friends (Baker and Oswald, 2010). Shyness was found to be mediating the negative relationship between Facebook addiction and subjective wellbeing (Satici, 2019). As lonely individuals and shy individuals feel comfortable with engaging in Facebook, which propel them to spend more time in Facebook (Ebeling-Witte et al., 2007; Caplan, 2010).

1.4.2. Rationale

Since the individual's personality is a major influence on their behaviour, it is logical to figure out which personality traits are more prone to Facebook addiction. This could help health care providers build more effective screening tools to guide subsequent therapy for Facebook addicted people (Błachnio et al., 2016). Identifying personality variables that act as risk factors for Facebook addiction is important not only for better understanding of the addiction, but also for prevention and therapy, since it indicates key personality factors that should be addressed in such interventions.

The results of an individual study would offer skewed picture if it aims to recommend various therapies and policy changes. In order to realize this, we planned to conduct a meta-analysis on the relation between personality traits and Facebook addiction. The meta-analysis' findings would provide a clearer picture of the issue under investigation. This study planned to carry out a meta-analysis.

1.4.3. Hypotheses

H1. Extraversion will be positively related to Facebook addiction.

H2. Agreeableness will be negatively related to Facebook addiction.

H3. Conscientiousness will be negatively related to Facebook addiction.

H4. Openness to experience will be negatively related to Facebook addiction.

H5. Neuroticism will be positively related to Facebook addiction.

H6. Narcissism will be positively related to Facebook addiction.

H7. Loneliness will be positively related to Facebook addiction.

H8. Shyness will be positively related to Facebook addiction.

H9. Impulsivity will be positively related to Facebook addiction.

2. Method

Various methods were employed to select and finalize studies which suits the aims and scopes of our meta-analysis. Initially, we started off with searching articles in march 2021 through various databases like Scopus, web of science, psych info, social science abstracts and other major databases. We searched with following terms “Facebook addiction and personality”, “Facebook abuse and personality”, “Facebook overuse and personality”, “Facebook addiction and big five traits”, “Facebook addiction and extraversion”, “Facebook addiction and neuroticism”, “Facebook addiction and conscientiousness”, “Facebook addiction and agreeableness”, “Facebook addiction and openness to experience”, “Facebook addiction and loneliness”, “Facebook addiction and narcissism”, “Facebook addiction and impulsivity”, “Facebook addiction and shyness”. Then, we have gone through reference sections of the collected articles and recently published meta-analysis articles on social media and personality for relevant articles. As per the PRISMA guidelines we have searched for unpublished works such as conference papers in sociological abstracts. We also searched for doctoral and PG dissertations through ProQuest and shodh ganga. Finally, we have visited the journals which are publishing social media related research. The journals are computers in human behaviors, personality and individual differences, journal of behavioral addictions. Eligible Studies from other languages were also included.

2.1. Inclusion criteria

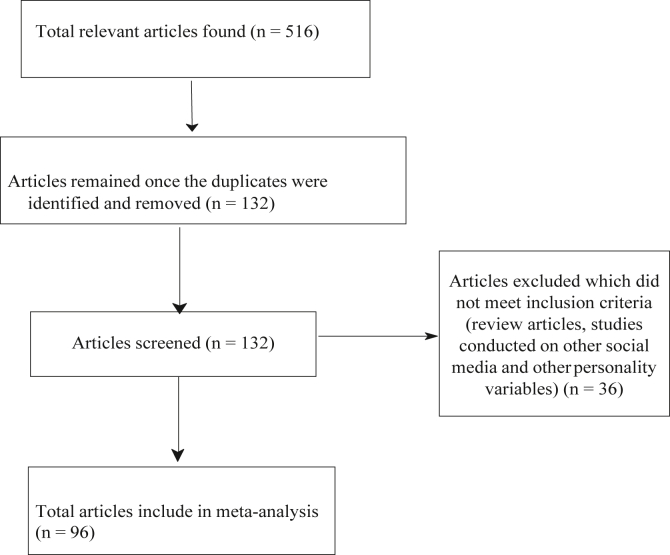

We agreed on the criteria that studies which dealt with Facebook addiction and chosen personality variables were included. Studies which dealt with social media in general or used scales which aimed at measuring overall social media use were omitted. Furthermore, studies which provided enough quantitative information such as correlation effect sizes were included. We have approached the authors to send us the effect sizes in studies which they did not provide effect sizes. After removing the duplicates, we are left with 96 articles, described in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram). Among these articles, 56 articles dealt with Facebook addiction and big five traits, 19 studies dealt with Facebook addiction and loneliness, 21 studies dealt with Facebook addiction and narcissism, 6 studies dealt with Facebook addiction and shyness, 10 studies dealt with Facebook addiction and impulsivity.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

All included studies were coded using Microsoft excel. The name of the authors, publication status, year of the publication, country, sample size, effect sizes, questionnaires used, reliability coefficients, percentage of boys and girls, mean and SD were included in the coding sheet.

2.2. Data analysis

The association between personality traits and Facebook addiction was computed by extracting the correlation coefficient (r) values given in the studies. When the correlation coefficient values were not provided, we have mailed the authors to provide the same. Remainder mail was sent after ten days if the authors did not respond to the initial mail. In case, the authors have not responded, if at all beta regression values were available, they were converted to correlation coefficient values using the formula r = .98β + .05 λ, where λ stands for 1 if β is a positive value and λ becomes 0 if the β is negative value (Peterson and Brown, 2005). The correlation values tend to be non-normally distributed which may lead to erroneous results if they are taken as raw scores. The r values were converted to z scores, which follows normal distribution, then final calculated values were converted back to r values for better interpretation. The analysis was performed with help of R software environment (R Development Core Team, 2015) using robumeta (Fisher and Tipton, 2015), metafor (Viechtbauer, 2010) packages. Since the included studies vary on different factors, Random effects model was used as it accounts for the random error as well as the heterogeneity of the studies. Q statistic measures the heterogeneity of the studies included. The statistically significant coefficient of Q statistic indicates the heterogeneity of the samples that included studies do not share common effect size. I2 indicates the proportion of observed variation due to the real difference between studies rather than the within study variance (Higgins et al., 2003). Random effects model was chosen to calculate the error variance of the include studies. The heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using Q statistics, I2 and tau coefficient values. Moderator analysis was performed to find out whether observed variance was influenced by moderator variables. Forest plots offers a visual landscape of studies included in the meta-analysis where it illustrates the heterogeneity of the studies.

2.3. Publication bias

Publication bias is a phenomenon where studies with significant findings have high probability of getting published and subsequently, they will be included in meta-analysis. In order to, not to succumb to publication bias meta-analysis should eliminate it. Funnel plot is visual tool to display if there is any publication bias in meta-analysis. But inferences about publication bias shall not be drawn merely based on funnel plot. It should be triangulated with statistical tests which can detect publication bias. Keeping this in view, publication bias was assessed using Kendal's tau method (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994) and eggers regression test (Egger et al., 1997). Absence of significance values implies that there is no publication bias.

3. Results

As shown in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram), a total of 96 studies were analysed in this metanalysis which comprises of 35608 participants (58% of females). The mean age of the participants was 24.97 and SD was 5.28. The studies ranged from different parts of the world; where 40 studies were conducted in eastern region and 56 studies were from western region. Facebook addiction was measured by various measures. Most of the studies used bergen Facebook addiction scale (Andreassen et al., 2012), or bergen social media addiction scale (Andreassen et al., 2012) and some studies used questionnaires like psychosocial aspects of Facebook use (Bodroza et al., 2009), Facebook intensity scale (Ellison et al., 2007), Facebook intrusion questionnaire (Elphinston and Noller, 2011), multidimensional Facebook intensity scale (Orosz, Király & Bőthe, 2016b), social media disorder scale (van den Eijnden et al., 2016). Big five personality traits were measured using both short and long questionnaires. Ten item personality inventory (Gosling et al., 2003) was the most used short and brief measure. Measures which are having bigger number of items like NEO five factor inventory revised (McCrae and Costa, 2004), big five inventory (John et al., 1991; John and Srivastava, 1999; Rammstedt and John, 2007), Hexaco personality inventory, Mini international personality item pool scale (Goldberg, 1999), big five personality scale (Horzum et al., 2017) were used.

Loneliness was measured by employing scales like UCLA loneliness scale (Russell et al., 1980) and social and emotional loneliness scale (Di Tommaso, Brannen & Best, 2004). Narcissism was measured by scales such as NPI-16 inventory (Ames et al., 2006), hypersensitive narcissism scale (Hendin and Cheek, 1997), pathological narcissism inventory (Schoenleber et al., 2015). Shyness was measured using scales like shyness scale (McCroskey and Richmond, 1982) and check & Buss shyness scale (Hopko et al., 2005). To measure impulsivity most of the studies used Barratt impulsivity scale (Patton et al., 1995), however some studies used UPPS-P impulsive behaviour scale (Whiteside et al., 2005) and couple of studies used delay discounting task (Rachlin et al., 1991).

The raw data from coding sheet was aggregated and showed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. Table 1 shows the summary of metanalysis results. The meta-analytic results showed that openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness were negatively correlated with Facebook addiction. The mean correlation of openness is r = -0.050, 95% CI [−0.08, -0.01], k = 51, Z = -2.85, p < .05; mean correlation of agreeableness is r = -0.069, 95% CI [−0.095, -0.042], k = 49, Z = -5.09, p < .05; mean correlation of conscientiousness is r = -0.145, 95% CI [−0.184, -0.107], k = 49, Z = -7.30, p < .01. Loneliness, narcissism and impulsivity were positively correlated with Facebook addiction. The mean correlation of loneliness is r = 0.231, 95% CI [0.186, 0.274], k = 19, Z = 9.88, p < .01; mean correlation of narcissism is r = 0.228, 95% CI [0.121, 0.329], k = 21, Z = 4.11, p < .01; mean correlation of impulsivity is r = 0.254, 95% CI [0.182, 0.322], k = 10, Z = 6.77, p < .01. Extraversion, neuroticism and shyness were not correlated with Facebook addiction. The mean correlation of extraversion is r = 0.009, 95% CI [−0.024, 0.041], k = 53, Z = 0.51; mean correlation of neuroticism is r = 0.032, 95% CI [−0.030, 0.094], k = 57, Z = 1.01; mean correlation of shyness is r = 0.198, 95% CI [0.140, 0.254], k = 6, Z = 6.62.

Table 1.

Summary of meta analysis results.

| k | N | ES | 95% CI | Z | Q | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| extraversion | 53 | 25133 | 0.009 | -0.024, 0.041 | 0.51 | 349.35∗ | 84.27 |

| openness | 51 | 24348 | -0.050 | -0.08, -0.01 | -2.85∗ | 295.35∗ | 85.74 |

| neuroticism | 57 | 27325 | 0.032 | -0.030, 0.094 | 1.01 | 1326.9379∗ | 96.18 |

| agreeableness | 49 | 24363 | -0.069 | -0.095, -0.042 | -5.09∗ | 187.94∗ | 75.17 |

| conscientiousness | 49 | 24363 | -0.145 | -0.184, -0.107 | -7.30∗∗ | 409.02∗ | 89.06 |

| loneliness | 19 | 7865 | 0.231 | 0.186, 0.274 | 9.88∗∗ | 71.45∗∗ | 74.90 |

| narcissism | 21 | 5209 | 0.228 | 0.121, 0.329 | 4.11∗∗ | 393.72∗∗ | 95.59 |

| impulsivity | 10 | 2781 | 0.254 | 0.182, 0.322 | 6.77∗∗ | 26.47∗∗ | 70.03 |

| shyness | 6 | 2596 | 0.198 | 0.140, 0.254 | 6.62∗∗ | 9.3873 | 50.2973 |

Table 2.

Summary of moderator analysis.

| Mean age | Sample size | Geographical location | FB scales | Personality scales | Publication status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| extraversion | 0.0048 | -0.0000 | 0.2278∗ | 0.1203∗ | 0.1562∗ | 0.0132 |

| openness | 0.008∗∗ | -0.0001 | -0.0598 | -0.0149 | -0.0300 | 0.0812 |

| neuroticism | 0.0122 | -0.0000 | 0.0719 | 0.33∗ | 0.07∗ | 0.42∗ |

| agreeableness | 0.0014 | 0.00 | 0.0626∗∗ | 0.0211 | 0.0601∗∗ | 0.0958 |

| conscientiousness | 0.0006 | 0.0001 | -0.29∗ | 0.35∗ | 0.10∗ | -0.0944 |

| loneliness | 0.0043 | -0.0001 | 0.0512 | 0.1356 | 0.1104 | 0.0057 |

| narcissism | 0.0022 | -0.0000 | -0.1635 | 0.2963 | 0.0500 | 0.2010 |

| impulsivity | 0.0166 | -0.0002 | -0.28∗∗ | 0.2618 | 0.1180 | 0.27∗∗ |

| shyness | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Table 3.

Summary of publication Bias.

| Kendall's rank correlation |

Egger's test |

N of studies to be imputed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tau | p | Z | p | ||

| extraversion | -0.0403 | 0.6728 | 0.9816 | 0.326 | 0 |

| openness | 0.0444 | 0.6489 | 0.8136 | 0.4159 | 0 |

| neuroticism | 0.0518 | 0.5721 | 0.8424 | 0.3995 | 0 |

| agreeableness | 0.0241 | 0.809 | 0.2638 | 0.7919 | 0 |

| conscientiousness | -0.0894 | 0.3695 | -0.9840 | 0.3251 | 7 |

| loneliness | 0.1298 | 0.4406 | 0.7501 | 0.4532 | 1 |

| narcissism | -0.0096 | 0.9518 | -0.2906 | 0.7713 | 6 |

| impulsivity | 0.1111 | 0.7614 | 0.8922 | 0.3723 | 3 |

| shyness | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | -0.0172 | 0.9863 | 0 |

3.1. Moderator analysis

Table 2 shows the results of moderator analysis. Various variables like mean age, sample size, geographical location, Facebook addiction scales, personality scales, publication status were considered as moderators which can contribute to the variability of effect sizes. heterogeneity was significant with regard to extraversion Q (52) = 349.35, p < .05, I2 = 84.27%, and variables such as geographical location (β = 0.22, p < .05), Facebook addiction scales (β = 0.12, p < .05) and personality scales (β = 0.12, p < .05) moderated the relationship between Facebook addiction and extraversion. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the case of openness to experience Q (50) = 295.35, p <. 05, I2 = 85.74%, and this was moderated by only the mean age of the participants (β = 0.008, p < .01). significant heterogeneity emerged for neuroticism Q (56) = 1326.93, p < .05, I2 = 96.18%, and variables like Facebook addiction scales (β = 0.33, p < .05), personality scales (β = 0.07, p < .05) and publication status (β = 0.42, p < .05) emerged as significant moderators. Significant heterogeneity was found in agreeableness Q (48) = 187.94, p < .05, I2 = 75.17%; geographical location (β = 0.42, p < .01) and personality scales (β = 0.42, p < .01) moderated the relationship. Significant heterogeneity was noted with regard to conscientiousness Q (48) = 409.02, p < .05, I2 = 89.06, variables like geographical location (β = -0.29, p < .05), Facebook addiction scales (β = 0.35, p < .05) and personality scales (β = 0.10, p < .05) were found to be significant moderators. Significant heterogeneity was found in loneliness Q (18) = 71.45, p < .05, I2 = 74.90 and narcissism Q (20) = 393.72, p < .05, I2 = 95.59 but none of the moderator variables were found to be significant. Significant heterogeneity was noted with reference to impulsivity Q (9) = 26.47, p < .05, I2 = 70.03, variables such as geographical location (β = -0.28, p < .01) and publication status (β = 0.27, p < .01) have moderated the relationship.

3.2. Publication bias

The possibility of publication bias was assessed using Kendal's tau and eggers regression test methods. Table 3 shows the results of publication bias. The indicators suggested that there is a less probability of publication bias regarding the studies included in this meta-analysis. Neither Kendal's tau test nor eggers regression test indicated significant funnel plot asymmetry in chosen variables. Additionally, trim and fill method was used to know the number of studies needs to be imputed. It suggested that 7 studies need to be imputed for conscientiousness, 1 study for loneliness, 6 studies for narcissism, and 3 studies needs to be imputed for impulsivity.

4. Discussion

This study intended to investigate the associations between big five personality traits, narcissism, loneliness, shyness, impulsivity and Facebook addiction. A meta-analysis was conducted to know the relationship between personality variables and Facebook addiction.

Extraversion was not associated with Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 1 not supported), This finding is similar to most of the studies. In order to preserve their social relationships with others, extraverted individuals update their profiles, share images, respond to political matters. There is less probability that they become addicted to Facebook because they possess the ability to interact in offline world. So, Facebook may act as one of the tools to reach out to their friends; hence extraverted individuals may not spend much time in Facebook (Błachnio and Przepiorka, 2016).

Agreeableness was negatively associated with Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 2 supported). Agreeableness displayed significant negative correlation with Facebook addiction. As the fundamental nature of agreeableness is cooperative and friendly, agreeable individuals may not get addicted because addictive behaviour can be detrimental to their interpersonal relationships. So, high agreeableness may protect individuals against addictive behaviours (Weinstein and Lejoyeux, 2010; Andreassen et al., 2013). Agreeableness was found to be substantially associated to only Internet addiction, not Facebook addiction, according to Blachnio and Przepiorka (2016). Kuo and Tang (2014) found that low agreeable individuals tend to use Facebook for social purposes and Loiacono (2014) proved in their study that individuals who are highly agreeable prefer not to share personal information. The reluctance of high agreeable individuals may stop them from using Facebook intensively.

Conscientiousness was having significant negative correlation with Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 3 supported). The personality trait conscientiousness is characterised by reliability, responsibility, self-regulation, discipline. Conscientious individuals are more driven towards achieving their goals, being productive and efficient. Given this nature they may not spend much time in Facebook because it obstructs their desire to be productive. Therefore, conscientious individuals may not be addicted to Facebook. This is evident in many of the studies. Błachnio and Przepiorka (2016) found that conscientiousness was negatively related to internet and Facebook addiction, because conscientious individuals tend to use their time judiciously and they are likely to perceive spending time in Facebook as hindering (Ross et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2016). High conscientious individuals are highly organized and proactive in achieving their primary objective, goals and tasks rather than spending time in Facebook (Andreassen et al., 2012, 2013; Wilson et al., 2010) (McCormac et al., 2017).

The meta-analysis also found significant negative correlation between openness to experience and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 4 supported). “Individuals who are open to new experiences are very inquisitive, interested to experience new things. Given their nature they may not spend lot of time in Facebook because they may probably want to experience other things in life (Ross et al., 2009; Horzum et al., 2021).” This finding is contradictory to other studies findings where it was inferred that openness to experience is a significant predictor of Facebook addiction. Caci et al. (2017) found that high openness was related to Facebook dependency in Italy. Nikbin, Iranmanesh, and Foroughi (2020) conducted their study in turkey, reported that openness was significantly related to Facebook addiction. Błachnio and Przepiorka (2016) found the same evidence in polish sample also. Openness was found to be significantly associated with internet addiction and social media addiction (Hawi and Samaha, 2019; Zafar et al., 2018). Dalvi-Esfahani et al. (2019) used a novel approach called as DEMATEL (decision making trial and evaluation laboratory) and suggested that high openness to experience is certainly a risk factor of Facebook addiction.

Meta-analysis did not find any correlation between neuroticism and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 5 not supported). Neurotic individuals might use Facebook exclusively to self-validate and regulate their mood. Neurotic individuals may perceive it as a threat if other Facebook users present themselves in a positive and competitive way, thereby reducing time spent on Facebook (Wang et al., 2015; Hwang, 2017; Andreassen et al., 2013 & Marino et al., 2016a, b). Scherr and Brunet (2017) found that neuroticism mediated the certain motivations which can act as catalyst to Facebook usage. Sagioglou and Greitemeyer (2014) suggested a causal connection between the neuroticism and Facebook usage. Interestingly it's the engagement in Facebook caused the elevation of negative moods which are characteristics of neurotic people. It is affirmed in study done by Abbasi and Drouin (2019) where they found that neurotic individuals may use Facebook to experience mood bolstering but in turn it may further worsen their mood as they may come across different posts which trigger jealousy and envy. So, it can be inferred that neurotic people selectively use the Facebook features rather than spending significant amount of time in it.

Meta analysis found a positive correlation between narcissism and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 6 supported). The various features of Facebook provide the opportunity for narcissistic individuals to promote their grandiosity, which satisfies their need for admiration. Therefore, narcissistic individuals spend more time on Facebook and get addicted to it (Casale and Fioravanti, 2018). Narcissistic individuals tend to yearn for admiration, validation form others and are highly concerned about self-presentation, carving out impression of themselves to others. These characteristics are gratified in the Facebook environment. This combination of personal characteristics and nature of Facebook features to appease these characteristics push narcissistic individuals towards to addiction. This line of argument has been supported by many studies. Narcissistic individuals are prone to Facebook addiction as facebook gratifies their affiliation and self-assurance needs (Andreassen et al., 2017; Casale et al., 2016). The features such as status updates, posting selfies appeal to the core characteristics of narcissistic individuals which they might over engage and get addicted to it (Garcia and Sikström, 2014; Fox and Rooney, 2015; McCain et al., 2016; Pabian et al., 2015; March and McBean, 2018; Ryan and Xenos, 2011). Portraying ideal self-image and self-presentation seems to be prominent motives to engage in Facebook as high narcissistic individuals perceive Facebook to be suitable platform to present themselves (Nadkarni and Hofmann, 2012) (Mehdizadeh, 2010; Buffardi and Campbell, 2008).

Individuals high in narcissism tend to engage in ego enhancing activities through the medium of Facebook such as showcasing their ambitions, endorsing their successes as these kinds of activities are met with rewards in the form of likes and comments. Engaging in these activities might be highly gratifying to the narcissistic individuals as they repeat this action and get addicted to it (Andreassen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2012).

Meta analysis found significant positive correlation between loneliness and Facebook addiction (hypothesis 7 supported). The propensity for online social communication to compensate for the dearth of offline relationships puts lonely individuals at risk for Facebook addiction (Błachnio et al., 2016; Shettar et al., 2017). Lonely individuals perceive themselves as unskilled to navigate real life social interactions. This perception of themselves makes them turn towards social media where they feel comfortable in online social interactions. Lonely individuals view online social interactions as less threatening because they can stay anonymous while interacting and it does not demand much skills as it does in face-to-face interactions (Caplan, 2003). Lonely individuals receive online social support also (Johnstone et al., 2009). As the interaction in social media can reduce the perception of loneliness (Deters and Mehl, 2013). Furthermore, social media can be a platform in which lonely individuals create a virtual identity (Guedes et al., 2016). Finally, interacting in Facebook can satisfy psychological, emotional and interpersonal needs which are not developed in off line relationships. This acts as compensatory mechanism for lonely individuals (Skues et al., 2012).

Meta-analysis found a significant positive correlation between shyness and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 8 supported), which is in line with the finding by Orr et al. (2009) which stated that shyness was positively associated with time spent on Facebook study but contradicts the findings of Ryan and Xenos (2011) who found that shyness was not associated with frequency of Facebook use. The relation between shyness and Facebook is contentious. The study by Baker and Oswald (2010) found that shy individuals use Facebook to know about peers and report perceived closeness, but Sheldon (2013) found that shy individuals self-disclose more to an offline friend than Facebook friends. So, shy individuals Facebook use could be goal-directed; they might use Facebook as a tool to navigate the matrix of interpersonal relations rather than solely depend upon it, which has the risk of getting addicted.

Meta-analysis found a significant positive correlation between impulsivity and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 9 supported). Meta analysis finding is supported by various studies in which they found that impulsivity was associated with Facebook addiction and problematic Facebook use (Delaney et al., 2018 & Orosz et al., 2016a, b). Impulsivity is one of the major contributing factors in other major addictions like drug, alcohol, gambling, internet addictions. Subsequently, it is assumed that individuals who are highly impulsive are at risk for Facebook addiction. This assumption was proved by some of the research studies. Cudo et al. (2020) & Rothen et al. (2018), found that impulsivity predicted Facebook addiction. Highly impulsive individuals engage in intensive use of Facebook which may lead to dysfunctional compared to low impulsive individuals.

Though impulsive individuals engage in rigid behaviours it may not always be problematic (Orosz et al., 2016a, b). Impulsivity is a common feature in other addictions like substance abuse, compulsive buying, binge eating and gambling because these addictions are associated with strong physiological reward pathways and material gains, whereas it is may not be the case for Facebook addiction. It's likely that Facebook lacks the high levels of positive reinforcement that drug abuse and some behavioural addictions do (Fowler et al., 2020).

This study found some interesting results. Even though this study found significant results, the effect sizes are low to moderate. As this is true to some other studies which found low to moderate effect sizes. The small amount variance explained by personality traits regarding Facebook addiction was found in many studies. Wilson et al. (2010) reported 8.5% of variance Błachnio and Przepiorka (2016) reported 6% of the variance and Hughes et al. (2012) reported 12.7% variance. The probable explanation could be that some other factors like, motivation, self-concept, might have better explanatory power than personality traits and the displayed behaviours might be far more limited and narrower when compared to offline setting therefore there is a less probability of correlation.

The less effect sizes make sense when we look at the results of moderator analysis which was performed as part of the meta-analysis. The significant correlations might not be solely achieved by the variance accountability of the personality variables rather it could be because of the moderator variables like geographical location, type of questionnaires used, publication status of the articles. Moderator analysis revealed that the type of questionnaires used to measure personality variables and Facebook addiction moderated the link between extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness. Which implies that the number of items in a questionnaire and the way it is framed could be reason for the significant result rather than the personality variables. Geographical location also moderated the link between extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, impulsivity and Facebook addiction. It can be inferred that the link between personality variables and Facebook addiction is contingent and depend upon the extent of these personality variables exist in the different countries. Different relationships between country, personality, and Facebook intrusion could indicate that such relationships aren't universal (Blachnio et al., 2016). Mean age moderated the link between openness to experience and Facebook addiction. Publication status moderated the link between impulsivity and Facebook addiction. This point towards the possibility that a greater number of studies with significant positive results were published rather than the studies with negative results.

4.1. Summary of key findings

Meta analysis found that agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience were significantly negatively correlated with Facebook addiction. Apart from big five traits, loneliness, narcissism, impulsivity and shyness were having significant positive correlation with Facebook addiction. Other variables like geographical location, type of questionnaires used and publication status also moderated the link between personality traits and Facebook addiction. To large extent, meta-analysis results were conforming to the findings of the previous literature.

4.2. Implications and recommendations

The meta-analysis results found that particular personality traits were correlated with Facebook addiction as they function through compensatory mechanism in Facebook realm. on an academic level, it can have implications as to investigate the relationship between personality traits and various specific features of social media which are assumed. On a practical level, it can have implications in designing psychotherapies tailored to vulnerable personality traits and varying Facebook addiction levels. These findings illuminate on how Facebook is instrumental in satisfying interpersonal needs by acting as compensatory mechanism. This insight could be helpful to clinicians to deal with individuals who are addicted to social media such as Facebook. Finally, this study results also can have implications on how the social media features are designed; especially not to encourage addictive level usage.

Future studies can focus on the underlying motivations and gratifications when they engage in an addictive level usage. Why and how, in spite of being detrimental, the usage of social networking platforms is still popular and is increasing across the world can also be an essential area to investigate. To counteract social media's harmful impacts, future research should focus on how the time spent on social networking platforms can be time well spent, designing algorithms which will prioritize our wellbeing, nudges our excessive usage, prompting cooperative behaviours.

4.3. Limitations

Few studies could not be included in this meta-analysis as those studies did not provide correlation coefficients. Shyness and impulsivity have been the subject of few investigations. As a result, fewer studies were included in the meta-analysis, and the meta-analysis results may be skewed as a result.

5. Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed the interesting relationships between personality traits and Facebook addiction. Although there is a link between personality factors and Facebook addiction, the impact sizes of these links are moderate, according to this meta-analysis. Finally, the link between personality traits and Facebook addiction is moderated by various other variables like the questionnaire's used, publication status and geographical location.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Rajesh Thipparapu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Babu Rangaiah: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abbasi I., Drouin M. Neuroticism and Facebook addiction: how social media can affect mood? Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2019;47(4):199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ames D.R., Rose P., Anderson C.P. The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. J. Res. Pers. 2006;40:440–450. [Google Scholar]

- Amichai-Hamburger Y. Internet and personality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2002;18(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Billieux J., Griffiths M.D., Kuss D.J., Demetrovics Z., Mazzoni E., Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016;30(2):252. doi: 10.1037/adb0000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Griffiths M.D., Gjertsen S.R., Krossbakken E., Kvam S., Pallesen S. The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. J. Behav. Addic. 2013;2(2):90–99. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Pallesen S., Griffiths M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017;64:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Torsheim T., Pallesen S. Predictors of use of social network sites at work—a specific type of cyber loafing. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2014;19(4):906–921. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G.S., Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012;110(2):501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen S.C., Pallesen S. Social network site addiction-an overview. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2014;20(25):4053–4061. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel H., Gerlach A.L., Crusius J. The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016;9:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Carrión Ó., Pöppel E. Dopamine, learning, and reward-seeking behavior. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 2007 doi: 10.55782/ane-2007-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko P.A., Balcerowska J.M., Bereznowski P., Biernatowska A., Pallesen S., Andreassen C.S. Facebook addiction among Polish undergraduate students: validity of measurement and relationship with personality and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018;85:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Aung E.E.S., Tin O. 2020. Facebook Addiction and Loneliness of university Students from Sagaing District. maas.edu.Mm. [Google Scholar]

- Baker L.R., Oswald D.L. Shyness and online social networking services. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2010;27(7):873–889. [Google Scholar]

- Balcerowska J.M., Bereznowski P., Biernatowska A., Atroszko P.A., Pallesen S., Andreassen C.S. Is it meaningful to distinguish between Facebook addiction and social networking sites addiction? Psychometric analysis of Facebook addiction and social networking sites addiction scales. Curr. Psychol. 2020:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Beard K.W. Internet addiction: a review of current assessment techniques and potential assessment questions. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2005;8(1):7–14. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Biometrics; 1994. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias; pp. 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biolcati R., Mancini G., Pupi V., Mugheddu V. Facebook addiction: onset predictors. J. Clin. Med. 2018;7(6):118. doi: 10.3390/jcm7060118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiorka A. Personality and positive orientation in Internet and Facebook addiction. An empirical report from Poland. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;59:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiórka A. Facebook intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissism, and life satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatr. Res. 2018;259:514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiórka A., Pantic I. Internet use, Facebook intrusion, and depression: results of a cross-sectional study. Eur. Psychiatr. 2015;30(6):681–684. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiorka A., Pantic I. Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;55:701–705. [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiorka A., Senol-Durak E., Durak M., Sherstyuk L. The role of personality traits in Facebook and Internet addictions: a study on Polish, Turkish, and Ukrainian samples. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;68:269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bodroza B., Popov B., Poljak I. Procena Psiholoških I Psihopatoloških Fenomena (Assessment of Psychological and Psychopathological Constructs) 2009. Procena virtuelnih ponašanja u društvenim mrezama (Assessment of virtual behaviour in social networking sites) pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D.M., Ellison N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2007;13(1):210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Bierhoff H.W., Rohmann E., Raeder F., Margraf J. The relationship between narcissism, intensity of Facebook use, Facebook flow and Facebook addiction. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020;11 doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J. Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German students—a longitudinal approach. PLoS One. 2017;12(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J., Köllner V. Addicted to facebook? Relationship between facebook addiction disorder, duration of facebook use and narcissism in an inpatient sample. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;273:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Schillack H., Margraf J. Facebook addiction disorder in Germany. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018;21(7):450–456. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2018.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffardi L.E., Campbell W.K. Narcissism and social networking web sites. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008;34(10):1303–1314. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caci B., Cardaci M., Scrima F., Tabacchi M.E. The dimensions of Facebook addiction as measured by Facebook Addiction Italian Questionnaire and their relationships with individual differences. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017;20(4):251–258. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caers R., De Feyter T., De Couck M., Stough T., Vigna C., Du Bois C. Facebook: a literature review. New Media Soc. 2013;15(6):982–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Çapan B.E., Sarıçalı M. The role of social and emotional loneliness in problematic Facebook use. 2016. http://abakus.inonu.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/11616/8136

- Caplan S.E. Preference for online social interaction: a theory of problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being. Commun. Res. 2003;30(6):625–648. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan S.E. A social skill account of problematic Internet use. J. Commun. 2005;55(4):721–736. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan S.E. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: a two-step approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010;26:1089–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Fioravanti G. Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: the need to be admired and the need to belong. Addict. Behav. 2018;76:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Fioravanti G., Rugai L. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissists: who is at higher risk for social networking addiction? Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016;19(8):510–515. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C., Condron L., Belland J.C. A review of the research on Internet addiction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2005;17:363–388. [Google Scholar]

- Cudo A., Wojtasiński M., Tużnik P., Griffiths M.D., Zabielska-Mendyk E. Problematic Facebook use and problematic video gaming as mediators of relationship between impulsivity and life satisfaction among female and male gamers. PLoS One. 2020;15(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvi-Esfahani M., Niknafs A., Kuss D.J., Nilashi M., Afrough S. Social media addiction: applying the DEMATEL approach. Telematics Inf. 2019;43 [Google Scholar]

- Delaney D., Stein L.A.R., Gruber R. Facebook addiction and impulsive decision-making. Addiction Res. Theor. 2018;26(6):478–486. [Google Scholar]

- Deters F.G., Mehl M.R. Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013;4(5):579–586. doi: 10.1177/1948550612469233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso E., Brannen C., Best L.A. Measurement and validity characteristics of the short version of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004;64(1):99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ebeling-Witte S., Frank M.L., Lester D. Shyness, internet use, and personality. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007;10:713–716. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Elphinston R.A., Noller P. Time to Face It! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011;14(11):631–635. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erevik E.K., Pallesen S., Andreassen C.S., Vedaa Ø., Torsheim T. Who is watching user-generated alcohol posts on social media? Addict. Behav. 2018;78:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eşkisu M., Hoşoğlu R., Rasmussen K. An investigation of the relationship between Facebook usage, Big Five, self-esteem and narcissism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;69:294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Z., Tipton E. R PackageVersion1.6; 2015. Robumeta:Robust variance meta- regression. Availableat:http://CRAN.R-project. org/package=robumeta. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske D.W. Consistency of the factorial structures of personality ratings from different sources. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1949;44(3):329–344. doi: 10.1037/h0057198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J., Gullo M.J., Elphinston R.A. Impulsivity traits and Facebook addiction in young people and the potential mediating role of coping styles. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2020;161 [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Rooney M.C. The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2015;76:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D., Sikström S. The dark side of Facebook: semantic representations of status updates predict the Dark Triad of personality. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2014;67:92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L.R. In: Personality Psychology in Europe. Mervielde I., Deary I., De Fruyt F., Ostendorf F., editors. Vol. 7. Tilburg University; Tilburg, The Netherlands: 1999. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models; pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S.D., Rentfrow P.J., Swann W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 2003;37(6):504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Grant J.E., Potenza M.N., Weinstein A., Gorelick D.A. Introduction to behavioral addictions. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):233–241. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.491884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use. 2005;10(4):191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes E., Nardi A.E., Guimarães F.M.C.L., Machado S., King A.L.S. Social networking, a new online addiction: a review of Facebook and other addiction disorders. Med. Exp. 2016;3(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hawi N., Samaha M. Identifying commonalities and differences in personality characteristics of Internet and social media addiction profiles: traits, self-esteem, and self-construal. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019;38(2):110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L.M., Zimbardo P.G., Carducci B.J. In: The Corsini Encyclopaedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science. third ed. Craighead W.E., Nemeroff C.B., editors. Wiley; New York: 2001. Shyness; pp. 1522–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Hendin H.M., Cheek J.M. Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: a re-examination of Murray's Narcism Scale. J. Res. Pers. 1997;31(4):588–599. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T.T.Q. Facebook addiction and depression: loneliness as a moderator and poor sleep quality as a mediator. Telematics Inf. 2021;61 [Google Scholar]

- Hopko D.R., Stowell J., Jones W.H., Armento M.E., Cheek J.M. Psychometric properties of the revised Cheek and Buss shyness scale. J. Pers. Assess. 2005;84(2):185–192. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8402_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn L. Vol. 1. PC Magazine; 2012. https://uk.pcmag.com/web-publishing/66544/study-finds-chemicalreason-behind-facebook-addiction (February 8). Study Finds Chemical Reason behind Facebook ‘addiction’). [Google Scholar]

- Horzum M.B., Canan Güngören Ö., Gür Erdoğan D. The influence of chronotype, personality, sex, and sleep duration on Facebook addiction of university students in Turkey. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2021:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Horzum M.B., Tuncay A.Y.A.S., Padir M.A. Adaptation of big five personality traits scale to Turkish culture. Sakarya Univ. J. Educ. 2017;7(2):398–408. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D.J., Rowe M., Batey M., Lee A. A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012;28(2):561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H.S. The influence of personality traits on the facebook addiction. KSII Transactions on Internet and Information Systems. 2017;11(2):1032–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh M., Foroughi B., Nikbin D., Hyun S.S. Shyness, self-esteem, and loneliness as causes of FA: the moderating effect of low self-control. Curr. Psychol. 2021;40(11):5358–5369. [Google Scholar]

- John O.P., Srivastava S. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality. Theo. Res. 1999;2:102–138. [Google Scholar]

- John O.P., Donahue E.M., Kentle R.L. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 1991. The Big Five Inventory-Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone M.-L., Todd S., Chua A. In: AP - Asia-Pacific Advances in Consumer Research. Samu S., Vaidyanathan R., Chakravarti D., editors. Association for Consumer Research; Duluth: 2009. Facebook: making social connections; pp. 234–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kanat-Maymon Y., Almog L., Cohen R., Amichai-Hamburger Y. Contingent self-worth and Facebook addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018;88:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner P.A., Karpinski A.C. Facebook® and academic performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010;26(6):1237–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T., Tang H.L. Relationships among personality traits, facebook usages, and leisure activities - a case of Taiwanese college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;31:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss D.J., Griffiths M.D. Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2011;8(9):3528–3552. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss D.J., Billieux J. Technological addictions: conceptualisation, measurement, etiology and treatment. Addict. Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiacono E.T. Self-disclosure behavior on social networking web sites. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014;19(2):66–94. [Google Scholar]

- Macït H.B., Macït G., Güngör O. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi. Vol. 5. 2018. A research on social media addiction and dopamine driven feedback; pp. 882–897. (3) [Google Scholar]

- March E., McBean T. New evidence shows self-esteem moderates the relationship between narcissism and selfies. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018;130:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Vieno A., Moss A.C., Caselli G., Nikčević A.V., Spada M.M. Personality, motives and metacognitions as predictors of problematic Facebook use in university students. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2016;101:70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Vieno A., Pastore M., Albery I.P., Frings D., Spada M.M. Modeling the contribution of personality, social identity and social norms to problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2016;63:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino Claudia, Gini Gianluca, Vieno Alessio, Marcantonio M., Spada A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018;83:262–277. [Google Scholar]

- McCain J.L., Borg Z.G., Rothenberg A.H., Churillo K.M., Weiler P., Campbell W.K. Personality and selfies: narcissism and the dark triad. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;64:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- McCormac A., Zwaans T., Parsons K., Calic D., Butavicius M., Pattinson M. Individual differences and information security awareness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;69:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T. A contemplated revision of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2004;36:587–596. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T., Jr. A five-factor theory of personality. Handb. Person.: Theo. Res. 1999;2:139–153. [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey J.C., Richmond V.P. Communication apprehension and shyness: conceptual and operational distinctions. Commun. Stud. 1982;33(3):458–468. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh S. Self-presentation 2.0: narcissism and self-esteem on facebook. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010;13(4):357–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli S., Cardaci M., Scrima F., Caci B. Time perspective and Facebook addiction: the moderating role of neuroticism. Curr. Psychol. 2021:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F.G., Barratt E.S., Dougherty D.M., Schmitz J.M., Swann A.C. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2001;158(11):1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C., Bey K., Sha P., Li M., Chen Y.F., Liu W.Y., Zhu Y.K., Li C.B., Markett S., Keiper J., Reuter M. Is it meaningful to distinguish between generalized and specific Internet addiction? Evidence from a cross-cultural study from Germany, Sweden, Taiwan and China. Asia Pac. Psychiatr. 2015;7(1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/appy.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C., Lachmann B., Herrlich M., Zweig K. Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(14):2612. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A., Hofmann S.G. Why do people use Facebook? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2012;52(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikbin D., Iranmanesh M., Foroughi B. Personality traits, psychological well-being, facebook addiction, health and performance: testing their relationships. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020;2020:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oldmeadow J.A., Quinn S., Kowert R. Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013;29(3):1142–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Orben A. University of Oxford; 2019. Teens, Screens and Well-Being: an Improved Approach (PhD Thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Orben A. Teenagers, screens and social media: a narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz G., Tóth-Király I., Bőthe B. Four facets of Facebook intensity—the development of the multidimensional Facebook intensity scale. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2016;100:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Orosz G., Vallerand R.J., Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Paskuj B. On the correlates of passion for screen-based behaviours: the case of impulsivity and the problematic and non-problematic Facebook use and TV series watching. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2016;101:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Orr E.S., Sisic M., Ross C., Simmering M.G., Arseneault J.M., Orr R.R. The influence of shyness on the use of Facebook in an undergraduate sample. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009;12(3):337–340. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabian S., De Backer C.J., Vandebosch H. Dark Triad personality traits and adolescent cyber-aggression. Pers. Individ. Diff. 2015;75:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Patton J.H., Stanford M.S., Barratt E.S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone M.A. Alfred University; New York: 2016. #FoMO: Establishing Validity of the Fear of Missing Out Scale with an Adolescent Population. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R.A., Brown S.P. On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005;90(1):175. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pies R. Should DSM-V designate “Internet addiction” a mental disorder? Psychiatry. 2009;6(2):31–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli R. Internet addiction update: diagnostic criteria, assessment and prevalence. Neuropsychiatry. 2017;7(1):4–8. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2015. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H., Raineri A., Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 1991;55(2):233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim S., Pervez S., Andleeb S. Facebook addiction and its relationship with self-esteem and narcissism. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2020;14(1) [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt B., John O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10- item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J. Res. Pers. 2007;41(1):203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales F.L., Guajardo J.R.B., Medrano J.L.J. Addictive behavior to social networks and five personality traits in young people. Psychol. Stud. 2021;66(1):92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C., Orr E.S., Sisic M., Arseneault J.M., Simmering M.G., Orr R.R. Personality and motivations associated with facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009;25(2):578–586. [Google Scholar]

- Rothen S., Briefer J.F., Deleuze J., Karila L., Andreassen C.S., Achab S.…Billieux J. Disentangling the role of users’ preferences and impulsivity traits in problematic Facebook use. PLoS One. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. Living arrangements, social integration, and loneliness in later life: the case of physical disability. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009;50(4):460–475. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D., Peplau L.A., Cutrona C.E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980;39(3):472. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T., Chester A., Reece J., Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2014;3(3):133–148. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T., Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011;27(5):1658–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Sagioglou C., Greitemeyer T. Facebook’s emotional consequences: why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people still use it. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;35:359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Satici S.A. Facebook addiction and subjective well-being: a study of the mediating role of shyness and loneliness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addiction. 2019;17(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Satici S.A., Uysal R. Well-being and problematic Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;49:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Scherr S., Brunet A. Differential influences of depression and personality traits on the use of Facebook. Soc. Media Soc. 2017;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- Schoenleber M., Roche M.J., Wetzel E., Pincus A.L., Roberts B.W. Development of a brief version of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychol. Assess. 2015;27(4):1520. doi: 10.1037/pas0000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schyff V.K., Flowerday S., Kruger H., Patel N. Intensity of Facebook use: a personality-based perspective on dependency formation. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon P. Examining gender differences in self-disclosure on Facebook versus face-to-face. J. Soc. Med. Soc. 2013;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon P., Antony M.G., Sykes B. Predictors of problematic social media use: personality and life-position indicators. Psychol. Rep. 2021;124(3):1110–1133. doi: 10.1177/0033294120934706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shettar M., Karkal R., Kakunje A., Mendonsa R.D., Chandran V.M. Facebook addiction and loneliness in the post-graduate students of a university in southern India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2017;63(4):325–329. doi: 10.1177/0020764017705895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindermann C., Duke É., Montag C. Personality associations with Facebook use and tendencies towards Facebook use disorder. Addic. Behav. Rep. 2020;11 doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindermann C., Elhai J.D., Montag C. Predicting tendencies towards the disordered use of Facebook's social media platforms: on the role of personality, impulsivity, and social anxiety. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;285 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skues J.L., Williams B., Wise L. The effects of personality traits, self-esteem, loneliness, and narcissism on Facebook use among university students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012;28(6):2414–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic V., Billieux J. Does the construct of Internet addiction reflect a single entity or a spectrum of disorders? Clin. Neuropsychiatry. 2017;14(1):5–10. [Google Scholar]