Abstract

Background

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors, 18-39 years at initial cancer diagnosis, often self-report negative consequences of cancer (treatment) for their career. Less is known, however, about the objective impact of cancer on employment and financial outcomes. This study examines the employment and financial outcomes of AYA cancer survivors with nationwide population-based registry data and compares the outcomes of AYAs with cancer with an age- and sex-matched control population at year of diagnosis, 1 year later (short-term) and 5 years later (long-term).

Patients and methods

A total of 2527 AYAs, diagnosed in 2013 with any invasive tumor type and who survived for 5 years, were identified from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (clinical and demographic data) and linked to Statistics Netherlands (demographic, employment and financial data). AYAs were matched 1 : 4 with a control population based on age and sex (10 108 controls). Analyses included descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, independent samples t-tests, McNemar tests and logistic regression.

Results

AYA cancer survivors were significantly less often employed compared with their controls 1 year (76.1% versus 79.5%, P < 0.001) and 5 years (79.3% versus 83.5%, P < 0.001) after diagnosis, and received more often disability benefits (9.9% versus 3.1% 1 year after diagnosis, P < 0.001; 11.2% versus 3.8% 5 years after diagnosis, P < 0.001). Unemployed AYAs were more often diagnosed with higher disease stages (P < 0.001), treated with chemotherapy (P < 0.001), radiotherapy (P < 0.001) or hormone therapy (P < 0.05) and less often with local surgery (P < 0.05) compared with employed AYAs 1 and 5 years after diagnosis.

Conclusion

Based on objective, nationwide, population-based registry data, AYAs’ employment and financial outcomes are significantly affected compared with age- and sex-matched controls, both short and long-term after cancer diagnosis. Providing support regarding employment and financial outcomes from diagnosis onwards may help AYAs finding their way (back) into society.

Key words: adolescents and young adults, AYAs, cancer, survivorship, employment and financial outcomes

Highlights

-

•

Based on objective data, AYAs’ employment and financial outcomes are significantly affected compared with matched controls.

-

•

AYAs were significantly more often unemployed compared with their controls 1 and 5 years after diagnosis.

-

•

AYAs received significantly more often disability benefits compared with their controls 1 and 5 years after diagnosis.

Introduction

Over the past three decades, overall cancer incidence among adolescents and young adults (AYAs, aged 18-39 years at initial diagnosis) has increased and with an overall 5-year relative survival of >85%, most AYA cancer survivors have a long life ahead of them.1,2 Adolescence and young adulthood are characterized by physical, cognitive, emotional and social transitions in which AYAs aim to achieve developmental milestones, like finding a job, becoming (financially) independent, forming relationships and starting a family.3 A cancer diagnosis, treatment and subsequent physical and psychosocial issues may interrupt and delay or even impede the achievement of these personal goals both in the short and long-term.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Employment is considered a key aspect of healthy AYA cancer survivorship. It enables AYAs to regain a sense of normalcy (i.e. structure), to recover their sense of identity and role in society with a range of positive consequences for their overall health and health-related quality of life (hrQoL) and provides AYAs with an income to become fully independent.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 As AYAs are all of working age with possibly many years of employment to follow and overall high survival rates, being employed is of importance for both the individual as well as for society.15 Unfortunately, many AYAs with cancer report undesired consequences of cancer (treatment) for their career, including unemployment, adverse employment changes (resulting in reduced income), career reorientation and a need to apply for disability benefits.6,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Although the majority of AYAs eventually return to work, studies suggest lower ratings of employed AYAs compared with the general population.16,23,24 As AYAs are at the start of their working career with possibly few or even no years of experience and often on temporary contracts, (re)integration into employment may be very challenging for them and may hinder AYAs from becoming financially independent and autonomous.23,25, 26, 27, 28 This can affect the patient’s family as well and may lead to distress and lower hrQoL.6,20,23,26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 It is unknown whether the social security system in the Netherlands, where one can apply for benefits in case of unemployment and (partial) disability, covers the possible negative consequences of a cancer diagnosis at adolescence or young adulthood.

Up until now, most research on the impact of cancer on the employment of AYA cancer survivors used self-reported instead of objective data measures. Although self-reported data will provide a good overview of the experiences of AYAs, these data are prone to recall bias and socially desirable answers.32 Understanding the objective employment and financial outcomes of AYA cancer survivors over time provides insight into who is at risk of poor outcomes and provides input for the development of relevant services and resources to serve those at risk. The aims of this nationwide population-based registry study are to (i) describe the baseline, short-term (defined as 1 year after diagnosis) and long-term (defined as 5 years after diagnosis) employment and financial outcomes of a Dutch cohort of AYA cancer survivors, (ii) compare these with the employment and financial outcomes of age- and sex-matched controls and (iii) examine factors associated with both short- and long-term employment among the AYAs. In this paper, employment comprises all forms of paid work (e.g. employee, self-employed) and does not include unpaid volunteering.

Methods

Data collection

The present study used objective, nationwide, population-based registry data from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) and Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Since 1989, the NCR obtains disease- and treatment-specific data on all cancer patients in the Netherlands.33 CBS systematically collects data on social and economic themes from all people in the Netherlands.34

AYA cancer survivors diagnosed in 2013 with their first invasive tumor of any type were selected from the NCR: all AYAs were between the age of 18 and 39 at diagnosis and survived for at least 5 years with no second cancer diagnosis. The NCR sent the AYAs’ demographic and clinical data (see Measures) to CBS, who linked the AYAs to their unique CBS identification number (ID), based on their 6-digit postal code, date of birth and sex. Then, the records were enriched with data from selected CBS registries on demographic characteristics [sex, date of birth (month and year), migration background, educational level, household and marital status] and employment and financial outcomes, based on their ID.35 Linkage was carried out for the years 2013 (baseline), 2014 (short-term: 1 year after baseline) and 2018 (long-term: 5 years after baseline). In case of multiple hits per year (multiple jobs at one moment in time), all hits were included in the database. Every case was matched 1 : 4, based on age (year and month of birth) and sex, to compose a control group from all people in the Netherlands based on CBS data.36 The control population consisted of people who were alive at baseline and not part of the AYA cancer survivor population. Controls had to be present in the CBS dataset regarding personal income to include those for whom 5 year follow-up was available and were similarly enriched with data from the selected CBS registries as the AYAs. Conditions that needed to be satisfied for all records included presence in the municipal personal records database and in the demographic datasets for all years to avoid inclusion of those who emigrated since 2013. The NCR and CBS both approved linkage, access and utilization of their data and results are based on calculations using non-public microdata from CBS.

Measures

Demographic characteristics: age at baseline, sex, educational level, marital status, household, migration background.

Employment and financial outcomes: employment (e.g. self-employed, employee, type of contract), benefits, financial (e.g. personal/household income, economic independence).

Clinical characteristics: date of diagnosis and death (if patient died >5 years after diagnosis and before data collection); age at diagnosis; vital status; follow-up in days; invasive tumor type; type of treatment; TNM (tumour–node–metastasis) classification, Figo (gynecological malignancies) or Ann Arbor (hematological malignancies); and type of hospital of treatment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Two-sided P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All variables were described as means and standard deviations (continuous data) or frequencies and percentages (categorical data). Independent samples t-tests (continuous data) and chi-square tests (categorical data) were carried out to compare (i) those linked with their CBS ID versus those not linked (to test the representativeness of the study sample); (ii) AYA cancer survivors versus the control population; and (iii) employed versus unemployed AYA cancer survivors (to describe differences). McNemar tests were carried out to determine whether there were differences in employment among the AYA cancer survivors over time. Logistic regression analyses were carried out to examine factors associated with employment in the short and long-term among the AYAs. Independent variables with P < 0.1 in univariable regression analyses were included in the multivariable logistic regression analyses, except for factors with high multi-collinearity. Tolerance, variance inflation factors and variance proportions were used to test for multi-collinearity. Missing data were not imputed and assumed missing at random.

Results

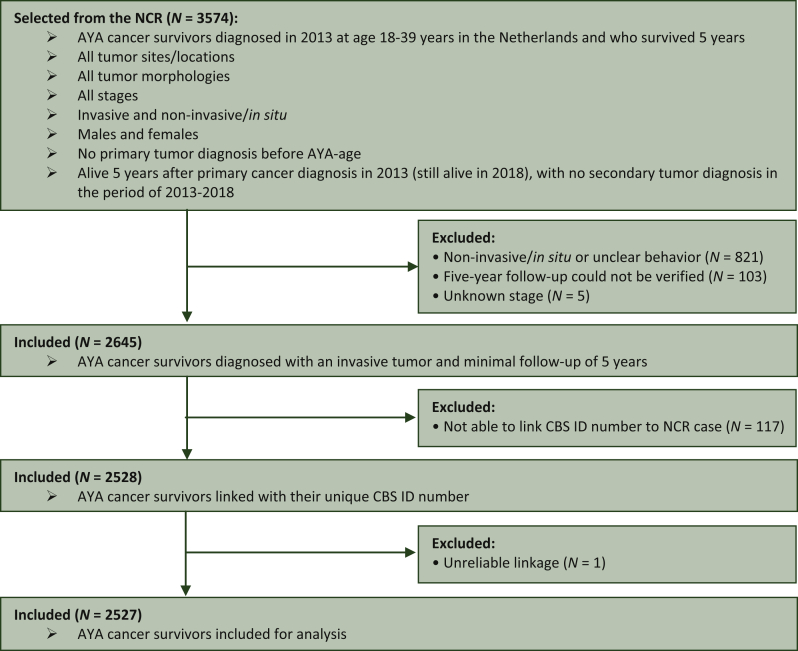

The NCR provided a cohort of 3574 AYA cancer survivors (Figure 1). Of these, 929 AYAs were excluded, as they did not satisfy the inclusion criteria and 117 AYAs were excluded, because CBS linkage was not possible. Eventually, 2528 AYAs were linked with their CBS ID (95.6% linkage rate). Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100521 provides an overview of the characteristics of the AYAs who were linked with their CBS ID and those not. Non-linked AYAs were younger (P < 0.001) and received treatment less often (P < 0.05, data not shown) compared with those linked with their CBS ID. One AYA was excluded, because of unreliable linkage. Finally, 2527 AYAs were matched (1 : 4) resulting in a control population of 10 108 records.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of case selection procedure.

AYA, adolescent and young adult; CBS, Statistics Netherlands; ID, identification; NCR, the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

AYA cancer survivors versus control population

Characteristics of the AYA cancer survivors and control population

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the AYA cancer survivors and their matched controls, and the clinical characteristics of the AYAs. Almost 60% was female, on average 32 years old at baseline and no differences were found based on marital status and educational level. Most common cancer types were breast (20.1%), skin (20.2%) and male genital organ (17.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the AYA cancer survivors and controls, and clinical characteristics of the AYA cancer survivors

| Baseline |

P value | One year after baseline (short-term) |

P value | Five years after baseline (long-term) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYAs (N = 2527) |

Controls (N = 10 108) |

AYAs (N = 2527) |

Controls (N = 10 108) |

AYAs (N = 2527) |

Controls (N = 10 108) |

||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 1068 (42.3) | 4272 (42.3) | 1.000 | — | — | — | — | — | – |

| Female | 1459 (57.7) | 5836 (57.7) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Age (at diagnosis) [mean (SD)] | 32.2 (5.7) | 32.2 (5.7) | 1.000 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Age (at diagnosis) | |||||||||

| 18-25 | 400 (15.8) | 1600 (15.8) | 1.000 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 26-39 | 2127 (84.2) | 8508 (84.2) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Country of birth | |||||||||

| The Netherlands | 2252 (89.1) | 8524 (84.3) | <0.001 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Other | 275 (10.9) | 1584 (15.7) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Migration backgrounda | |||||||||

| Suriname | 51 (2.0) | 276 (2.7) | <0.001 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Morocco | 56 (2.2) | 302 (3.0) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Indonesia | 29 (1.1) | 114 (1.1) | — | — | — | — | |||

| The Netherlands | 2018 (79.9) | 7508 (74.3) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Turkey | 77 (3.0) | 349 (3.5) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Poland | 24 (0.9) | 129 (1.3) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Other | 272 (10.8) | 1430 (14.1) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Generation | |||||||||

| Native | 2018 (79.9) | 7508 (74.3) | <0.001 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| First-generation immigrant | 252 (10.0) | 1476 (14.6) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Second-generation immigrant | 257 (10.2) | 1124 (11.1) | — | — | — | — | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Partner | 907 (35.9) | 3702 (36.6) | 0.494 | 955 (37.8) | 3874 (38.3) | 0.621 | 1124 (44.5) | 4419 (43.7) | 0.490 |

| No partner | 1620 (64.1) | 6406 (63.4) | 1572 (62.2) | 6234 (61.7) | 1403 (55.5) | 5689 (56.3) | |||

| Educational level (achieved) | |||||||||

| Lowh | 323 (12.8) | 1400 (13.9) | 0.313 | 315 (12.5) | 1334 (13.2) | 0.551 | 290 (11.5) | 1229 (12.2) | 0.612 |

| Middlei | 851 (33.7) | 3405 (33.7) | 852 (33.7) | 3387 (33.5) | 800 (31.7) | 3160 (31.3) | |||

| Highj | 842 (33.3) | 3266 (32.3) | 861 (34.1) | 3367 (33.3) | 967 (38.3) | 3823 (37.8) | |||

| Missing | 511 (20.2) | 2037 (20.2) | 499 (19.7) | 2020 (20.0) | 470 (18.6) | 1896 (18.8) | |||

| Educational level (followed) | |||||||||

| Lowh | 169 (6.7) | 737 (7.3) | 0.332 | 171 (6.8) | 749 (7.4) | 0.377 | 173 (6.8) | 736 (7.3) | 0.488 |

| Middlei | 713 (28.2) | 2929 (29.0) | 710 (28.1) | 2878 (28.5) | 699 (27.7) | 2858 (28.3) | |||

| Highj | 1134 (44.9) | 4405 (43.6) | 1147 (45.4) | 4461 (44.1) | 1185 (46.9) | 4618 (45.7) | |||

| Missing | 511 (20.2) | 2037 (20.2) | 499 (19.7) | 2020 (20.0) | 470 (18.6) | 1896 (18.8) | |||

| Type of household | |||||||||

| Single person | 466 (18.4) | 1781 (17.6) | 0.217 | 444 (17.6) | 1732 (17.1) | 0.067 | 408 (16.1) | 1608 (15.9) | 0.004 |

| Couple without children | 505 (20.0) | 1952 (19.3) | 497 (19.7) | 1855 (18.4) | 461 (18.2) | 1589 (15.7) | |||

| Couple with children | 1332 (52.7) | 5402 (53.4) | 1371 (54.3) | 5520 (54.6) | 1423 (56.3) | 5831 (57.7) | |||

| Otherk | 213 (8.4) | 972 (9.6) | 211 (8.3) | 1000 (9.9) | 231 (9.1) | 1079 (10.7) | |||

| Missing | 11 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Place in household | |||||||||

| Child living at home | 371 (14.7) | 1462 (14.5) | 0.381 | 336 (13.3) | 1255 (12.4) | 0.046 | 182 (7.2) | 673 (6.7) | 0.005 |

| Single | 466 (18.4) | 1781 (17.6) | 444 (17.6) | 1732 (17.1) | 408 (16.1) | 1608 (15.9) | |||

| Partner without children | 502 (19.9) | 1931 (19.1) | 495 (19.6) | 1838 (18.2) | 460 (18.2) | 1570 (15.5) | |||

| Partner with children | 1032 (40.8) | 4256 (42.1) | 1100 (43.5) | 4533 (44.8) | 1278 (50.6) | 5329 (52.7) | |||

| Parent in one-parent household | 89 (3.5) | 431 (4.3) | 101 (4.0) | 514 (5.1) | 149 (5.9) | 704 (7.0) | |||

| Otherl | 56 (2.2) | 246 (2.4) | 47 (1.9) | 235 (2.3) | 46 (1.8) | 223 (2.2) | |||

| Missing | 11 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Reference person of householdm | |||||||||

| No | 1404 (55.6) | 5658 (56.0) | 0.872 | 1391 (55.0) | 5472 (54.1) | 0.371 | 1291 (51.1) | 5082 (50.3) | 0.425 |

| Yes | 1112 (44.0) | 4449 (44.0) | 1132 (44.8) | 4635 (45.9) | 1232 (48.8) | 5025 (49.7) | |||

| Missing | 11 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Number of persons in household who are living-at-home child(ren) | |||||||||

| 0 children | 1016 (40.2) | 3923 (38.8) | 0.150 | 982 (38.9) | 3771 (37.3) | 0.135 | 907 (35.9) | 3358 (33.2) | 0.010 |

| 1-10 child(ren) | 1500 (59.4) | 6184 (61.2) | 1541 (61.0) | 6336 (62.7) | 1616 (63.9) | 6749 (66.8) | |||

| Missing | 11 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Type of cancer | |||||||||

| Bone, articular cartilage and soft tissues | 72 (2.8) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Breast | 508 (20.1) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Central nervous system | 80 (3.2) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Digestive tract | 120 (4.7) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Endocrine glands | 124 (4.9) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Female genital organs | 201 (8.0) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Hematological malignancies | 339 (13.4) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Head and neck | 45 (1.8) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Male genital organs | 444 (17.6) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Respiratory tract | 23 (0.9) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Skin | 510 (20.2) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Urinary tract | 51 (2.0) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Other/unspecified sitesb | 10 (0.4) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Type of hospital of treatment | |||||||||

| University hospital | 645 (25.5) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| General hospital | 751 (29.7) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Collaborating top clinical hospital | 1089 (43.1) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Otherc | 42 (1.7) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Organ surgery | |||||||||

| No | 1148 (45.4) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 1379 (54.6) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Local surgery | |||||||||

| No | 1812 (71.7) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 715 (28.3) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 1471 (58.2) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 1056 (41.8) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 1781 (70.5) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 746 (29.5) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Hormone therapy | |||||||||

| No | 2211 (87.5) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 316 (12.5) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Treatment receivedd | |||||||||

| No | 68 (2.7) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 2459 (97.3) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Stagee | |||||||||

| I | 1172 (59.0) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| II | 434 (21.8) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| III | 206 (10.4) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| IV | 47 (2.4) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Missing | 128 (6.4) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Figo stagef | |||||||||

| I | 162 (80.6) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| II | 23 (11.4) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| III | 13 (6.5) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| IV | 3 (1.5) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Ann Arbor stageg | |||||||||

| I | 34 (10.0) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| II | 95 (28.0) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| III | 31 (9.1) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| IV | 63 (18.6) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Missing | 116 (34.2) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

Independent samples t-tests and chi square tests were carried out to compare AYA cancer survivors with the control population.

AYA, adolescent and young adult; SD, standard deviation.

Countries ≥1% are displayed.

Unspecified sites, primary sites unknown or unknown tumor type and eye.

E.g. general practitioner, freely established specialist or foreign hospital.

Including patients treated with immunotherapy of whom <10 patients received this therapy.

Figo and Ann Arbor stage were not included in the stage variable.

Gynecological malignancies.

Hematological malignancies.

Primary school, junior high school or equivalent.

Senior high school or equivalent.

College/university.

Institutional households, one-parent household or any other household than already included.

Member of institutional household, reference person in other household or any other member than already included.

Member of the household to whom the positions of the other members of the household are determined.

Employment and financial outcomes of the AYA cancer survivors and control population

Table 2 provides an overview of the employment and financial outcomes of the AYA cancer survivors and their matched controls at baseline, short-term and long-term. Both 1 and 5 years after diagnosis, AYA cancer survivors were significantly less often employed compared with controls (76.1% versus 79.5%, and 79.3% versus 83.5%, respectively). The number of employed AYAs fluctuated significantly over time from 82.3% at baseline, decreasing to 76.1% 1 year after diagnosis and ending up with 79.3% 5 years after diagnosis (P < 0.001). The number of employed controls was more stable in the short-term (79.8% at baseline, 79.5% short-term) and eventually increased in the long-term (83.5%).

Table 2.

Short- and long-term employment and financial outcomes of the AYA cancer survivors and their matched controls

| Baseline |

P value | One year after baseline (short-term) |

P value | Five years after baseline (long-term) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYAs (N = 2527) |

Controls (N = 10 108) |

AYAs (N = 2527) |

Controls (N = 10 108) |

AYAs (N = 2527) |

Controls (N = 10 108) |

||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Employeda | |||||||||

| No | 440 (17.4) | 2037 (20.2) | 0.002 | 601 (23.8) | 2072 (20.5) | <0.001 | 522 (20.7) | 1669 (16.5) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2079 (82.3) | 8071 (79.8) | 1924 (76.1) | 8036 (79.5) | 2005 (79.3) | 8438 (83.5) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Employee | |||||||||

| No | 638 (25.2) | 2875 (28.4) | 0.002 | 810 (32.1) | 3002 (29.7) | 0.020 | 777 (30.7) | 2846 (28.2) | 0.010 |

| Yes | 1881 (74.4) | 7233 (71.6) | 1715 (67.9) | 7106 (70.3) | 1750 (69.3) | 7261 (71.8) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Self-employed | |||||||||

| No | 2321 (91.8) | 9248 (91.5) | 0.294 | 2316 (91.7) | 9148 (90.5) | 0.058 | 2272 (89.9) | 8907 (88.1) | 0.012 |

| Yes | 198 (7.8) | 860 (8.5) | 209 (8.3) | 960 (9.5) | 255 (10.1) | 1200 (11.9) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Unemployment benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2426 (96.0) | 9726 (96.2) | 0.837 | 2470 (97.7) | 9643 (95.4) | <0.001 | 2472 (97.8) | 9844 (97.4) | 0.222 |

| Yes | 93 (3.7) | 382 (3.8) | 55 (2.2) | 465 (4.6) | 55 (2.2) | 263 (2.6) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Social assistance benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2447 (96.8) | 9680 (95.8) | 0.002 | 2410 (95.4) | 9656 (95.5) | 0.857 | 2424 (95.9) | 9660 (95.6) | 0.445 |

| Yes | 72 (2.8) | 428 (4.2) | 115 (4.6) | 452 (4.5) | 103 (4.1) | 447 (4.4) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Social security benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2438 (96.5) | 9781 (96.8) | 0.961 | 2427 (96.0) | 9771 (96.7) | 0.177 | 2421 (95.8) | 9738 (96.3) | 0.199 |

| Yes | 81 (3.2) | 327 (3.2) | 98 (3.9) | 337 (3.3) | 106 (4.2) | 369 (3.7) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Sickness/disability benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2448 (96.9) | 9811 (97.1) | 0.749 | 2276 (90.1) | 9794 (96.9) | <0.001 | 2244 (88.8) | 9720 (96.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 71 (2.8) | 297 (2.9) | 249 (9.9) | 314 (3.1) | 283 (11.2) | 387 (3.8) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Student | |||||||||

| No | 2197 (86.9) | 8820 (87.3) | 0.957 | 2295 (90.8) | 9031 (89.3) | 0.023 | 2401 (95.0) | 9668 (95.6) | 0.162 |

| Yes | 322 (12.7) | 1288 (12.7) | 230 (9.1) | 1077 (10.7) | 126 (5.0) | 439 (4.3) | |||

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | — | 2 (0.1) | — | — | 1 (0.0) | |||

| Personal gross income [mean (SD)] | 33 681.23 (26 345.56) | 33 313.19 (27 199.77) | 0.542 | 34 644.23 (28 244.51) | 34 940.57 (28 512.06) | 0.640 | 41 910.92 (32 365.51) | 42 712.21 (33 693.16) | 0.282 |

| Economic independence of the person | |||||||||

| Not economically independent | 831 (32.9) | 3381 (33.4) | 0.652 | 888 (35.1) | 3246 (32.1) | 0.004 | 704 (27.9) | 2401 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Economically independent | 1659 (65.7) | 6607 (65.4) | 1610 (63.7) | 6726 (66.5) | 1801 (71.3) | 7577 (75.0) | |||

| Missing | 37 (1.5) | 120 (1.2) | 29 (1.1) | 136 (1.3) | 22 (0.9) | 130 (1.3) | |||

| Indicator person with income | |||||||||

| Without personal income | 80 (3.2) | 404 (4.0) | 0.055 | 94 (3.7) | 422 (4.2) | 0.299 | 86 (3.4) | 354 (3.5) | 0.792 |

| With personal income | 2426 (96.0) | 9654 (95.5) | 2422 (95.8) | 9638 (95.4) | 2437 (96.4) | 9713 (96.1) | |||

| Missing | 21 (0.8) | 50 (0.5) | 11 (0.4) | 48 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 41 (0.4) | |||

| Gross household income [mean (SD)] | 74 427.01 (47 271.13) | 74 009.69 (50 850.23) | 0.709 | 79 575.93 (63 985.44) | 77 314.30 (62 225.57) | 0.105 | 91 115.50 (82 067.50) | 89 256.17 (61 527.81) | 0.207 |

| Benefit dependence of household | |||||||||

| No benefit dependence of household | 1701 (67.3) | 6982 (69.1) | 0.123 | 1640 (64.9) | 6892 (68.2) | 0.001 | 1725 (68.3) | 7525 (74.4) | <0.001 |

| Benefit dependence of household | 789 (31.2) | 3006 (29.7) | 858 (34.0) | 3080 (30.5) | 780 (30.9) | 2453 (24.3) | |||

| Missing | 37 (1.5) | 120 (1.2) | 29 (1.1) | 136 (1.3) | 22 (0.9) | 130 (1.3) | |||

| Employees only | Baseline |

P value | One year after baseline (short-term) |

P value | Five years after baseline (long-term) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYAs (N = 1881) |

Controls (N = 7233) |

AYAs (N = 1715) |

Controls (N = 7106) |

AYAs (N = 1750) |

Controls (N = 7261) |

||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Number of employment hours [mean (SD)] | 114.83 (43.31) | 114.23 (43.61) | 0.592 | 117.80 (43.60) | 115.00 (43.87) | 0.018 | 116.98 (39.32) | 118.01 (38.11) | 0.315 |

| Type of contract | |||||||||

| Fixed term contract | 573 (30.5) | 2198 (30.4) | 0.968 | 432 (25.2) | 2053 (28.9) | 0.003 | 488 (27.9) | 1926 (26.5) | 0.198 |

| Permanent contract | 1259 (66.9) | 4791 (66.2) | 1239 (72.2) | 4800 (67.5) | 1217 (69.5) | 5086 (70.0) | |||

| Both contract types | 36 (1.9) | 143 (2.0) | 28 (1.6) | 137 (1.9) | 26 (1.5) | 148 (2.0) | |||

| Missing | 13 (0.7) | 101 (1.4) | 16 (0.9) | 116 (1.6) | 19 (1.1) | 101 (1.4) | |||

| Employment | |||||||||

| Full time | 854 (45.4) | 3261 (45.1) | 0.857 | 804 (46.9) | 3150 (44.3) | 0.240 | 771 (44.1) | 3164 (43.6) | 0.421 |

| Part time | 986 (52.4) | 3776 (52.2) | 879 (51.3) | 3767 (53.0) | 945 (54.0) | 3907 (53.8) | |||

| Both types of employment | 28 (1.5) | 95 (1.3) | 16 (0.9) | 73 (1.0) | 15 (0.9) | 89 (1.2) | |||

| Missing | 13 (0.7) | 101 (1.4) | 16 (0.9) | 116 (1.6) | 19 (1.1) | 101 (1.4) | |||

Independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests were carried out to compare AYA cancer survivors with the control population.

Frequencies ≤10 could not be displayed due to disclosure guidelines of CBS.

AYA, adolescent and young adult; SD, standard deviation.

Employment includes employees, self-employed and director-major stakeholders.

Controls were significantly more often employees, both short and long-term, compared with the AYA cancer survivors. Among the employees, no significant differences were seen regarding part-time or full-time employment. AYA employees had significantly more often a permanent contract 1 year after baseline compared with controls. This effect, however, was not observed 5 years after diagnosis (Table 2).

Controls received significantly more often social assistance benefit (i.e. benefit for which one can apply in case of little or no income to pay for necessary costs e.g. food, health insurance, rent) at baseline and unemployment benefits 1 year after baseline compared with the AYA cancer survivors (Table 2). AYA cancer survivors received significantly more often disability benefits compared with controls both short (9.9% versus 3.1%, P < 0.001) and long-term (11.2% versus 3.8%, P < 0.001). Personal and household income did not significantly differ between AYAs and controls for all time points. Economic independence, defined as the situation in which the personal net income from employment is higher than the net social assistance benefit for a single person, did not differ between AYA cancer survivors and controls at baseline. One and five years later, however, controls were more often economically independent compared with the AYAs. Controls were significantly more often studying 1 year after baseline than AYAs, but no significant difference was seen at baseline or 5 years later.

In contrast to baseline, the survivors’ households were significantly more often dependent on receiving benefits compared with the controls’ households, short- and long-term (Table 2).

AYA cancer survivors

Demographic and clinical characteristics, and employment and financial outcomes of (un)employed AYA cancer survivors

The percentage of unemployed AYAs significantly increases from baseline (17.4%) to 1 year later (23.8%) and still remains increased 5 years after diagnosis (20.7%) (P < 0.001). Employed AYAs were more often born in the Netherlands, had more often a partner and completed or followed high education compared with unemployed AYAs for all time points (Table 3). They were also significantly older at baseline (32.5 years versus 30.6 years) and 1 year after baseline (33.7 years versus 31.6 years), although no significant difference was seen 5 years after baseline. Females were significantly more often unemployed in the long-term than males (68.4% versus 31.6%). Unemployed AYAs 1 and 5 years after diagnosis were more often treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or hormone therapy, and less often with local surgery. Employed AYAs were significantly more often diagnosed with stage I compared with those unemployed 1 and 5 years after diagnosis.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, and employment and financial outcomes of (un)employed AYA cancer survivors

| Baseline |

P value | One year after baseline (short-term) |

P value | Five years after baseline (long-term) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed AYAs (N = 2079) |

Unemployed AYAs (N = 440) |

Employed AYAs (N = 1924) |

Unemployed AYAs (N = 601) |

Employed AYAs (N = 2005) |

Unemployed AYAs (N = 522) |

||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 884 (42.5) | 179 (40.7) | 0.478 | 831 (43.2) | 236 (39.3) | 0.089 | 903 (45.0) | 165 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1195 (57.5) | 261 (59.3) | 1093 (56.8) | 365 (60.7) | 1102 (55.0) | 357 (68.4) | |||

| Age [mean (SD)] | 32.5 (5.5) | 30.6 (6.5) | <0.001 | 33.7 (5.4) | 31.6 (6.5) | <0.001 | 37.2 (5.6) | 36.9 (6.1) | 0.234 |

| Country of birth | |||||||||

| The Netherlands | 1901 (91.4) | 350 (79.5) | <0.001 | 1765 (91.7) | 486 (80.9) | <0.001 | 1839 (91.7) | 413 (79.1) | <0.001 |

| Other | 178 (8.6) | 90 (20.5) | 159 (8.3) | 115 (19.1) | 166 (8.3) | 109 (20.9) | |||

| Migration backgrounda | |||||||||

| Suriname | 34 (1.6) | 16 (3.6) | <0.001 | 29 (1.5) | 22 (3.7) | <0.001 | 34 (1.7) | 17 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Morocco | 35 (1.7) | 21 (4.8) | 24 (1.2) | 32 (5.3) | 24 (1.2) | 32 (6.1) | |||

| Indonesia | 24 (1.2) | 5 (1.1) | 21 (1.1) | 8 (1.3) | 21 (1.0) | 8 (1.5) | |||

| The Netherlands | 1730 (83.2) | 287 (65.2) | 1620 (84.2) | 397 (66.1) | 1682 (83.9) | 336 (64.4) | |||

| Turkey | 44 (2.1) | 33 (7.5) | 36 (1.9) | 41 (6.8) | 29 (1.4) | 48 (9.2) | |||

| Poland | 15 (0.7) | 9 (2.0) | 16 (0.8) | 8 (1.3) | 17 (0.8) | 7 (1.3) | |||

| Other | 197 (9.5) | 69 (15.7) | 178 (9.3) | 93 (15.5) | 198 (9.9) | 74 (14.2) | |||

| Generation | |||||||||

| Native | 1730 (83.2) | 287 (65.2) | <0.001 | 1620 (84.2) | 397 (66.1) | <0.001 | 1682 (83.9) | 336 (64.4) | <0.001 |

| First-generation immigrant | 157 (7.6) | 88 (20.0) | 140 (7.3) | 111 (18.5) | 149 (7.4) | 103 (19.7) | |||

| Second-generation immigrant | 192 (9.2) | 65 (14.8) | 164 (8.5) | 93 (15.5) | 174 (8.7) | 83 (15.9) | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Partner | 773 (37.2) | 132 (30.0) | 0.004 | 775 (40.3) | 180 (30.0) | <0.001 | 914 (45.6) | 210 (40.2) | 0.028 |

| No partner | 1306 (62.8) | 308 (70.0) | 1149 (59.7) | 421 (70.0) | 1091 (54.4) | 312 (59.8) | |||

| Educational level (achieved) | |||||||||

| Lowb | 201 (9.7) | 122 (27.7) | <0.001 | 160 (8.3) | 155 (25.8) | <0.001 | 154 (7.7) | 136 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| Middlec | 658 (31.6) | 192 (43.6) | 582 (30.2) | 270 (44.9) | 605 (30.2) | 195 (37.4) | |||

| Highd | 775 (37.3) | 66 (15.0) | 752 (39.1) | 109 (18.1) | 863 (43.0) | 104 (19.9) | |||

| Missing | 445 (21.4) | 60 (13.6) | 430 (22.3) | 67 (11.1) | 383 (19.1) | 87 (16.7) | |||

| Educational level (followed) | |||||||||

| Lowb | 97 (4.7) | 72 (16.4) | <0.001 | 79 (4.1) | 92 (15.3) | <0.001 | 80 (4.0) | 93 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Middlec | 545 (26.2) | 167 (38.0) | 480 (24.9) | 230 (38.3) | 513 (25.6) | 186 (35.6) | |||

| Highd | 992 (47.7) | 141 (32.0) | 935 (48.6) | 212 (35.3) | 1029 (51.3) | 156 (29.9) | |||

| Missing | 445 (21.4) | 60 (13.6) | 430 (22.3) | 67 (11.1) | 383 (19.1) | 87 (16.7) | |||

| Type of household | |||||||||

| Single person | 383 (18.4) | 83 (18.9) | <0.001 | 329 (17.1) | 115 (19.1) | <0.001 | 306 (15.3) | 102 (19.5) | <0.001 |

| Couple without children | 454 (21.8) | 51 (11.6) | 421 (21.9) | 76 (12.6) | 386 (19.3) | 75 (14.4) | |||

| Couple with children | 1109 (53.3) | 223 (50.7) | 1056 (54.9) | 315 (52.4) | 1175 (58.6) | 248 (47.5) | |||

| Othere | 132 (6.3) | 81 (18.4) | 116 (6.0) | 95 (15.8) | 136 (6.8) | 95 (18.2) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | — | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | |||

| Place in household | |||||||||

| Child living at home | 267 (12.8) | 104 (23.6) | <0.001 | 200 (10.4) | 136 (22.6) | <0.001 | 127 (6.3) | 55 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Single | 383 (18.4) | 83 (18.9) | 329 (17.1) | 115 (19.1) | 306 (15.3) | 102 (19.5) | |||

| Partner without children | 451 (21.7) | 51 (11.6) | 420 (21.8) | 75 (12.5) | 385 (19.2) | 75 (14.4) | |||

| Partner with children | 888 (42.7) | 144 (32.7) | 899 (46.7) | 201 (33.4) | 1072 (53.5) | 206 (39.5) | |||

| Parent in one-parent household | 58 (2.8) | 31 (7.0) | 55 (2.9) | 46 (7.7) | 87 (4.3) | 62 (11.9) | |||

| Otherf | 31 (1.5) | 25 (5.7) | 19 (1.0) | 28 (4.7) | 26 (1.3) | 20 (3.8) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | — | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | |||

| Reference person of householdg | |||||||||

| No | 1124 (54.1) | 280 (63.6) | <0.001 | 1026 (53.3) | 365 (60.7) | 0.002 | 996 (49.7) | 295 (56.5) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 954 (45.9) | 158 (35.9) | 896 (46.6) | 236 (39.3) | 1007 (50.2) | 225 (43.1) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | — | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | |||

| Number of persons in household who are living-at-home child(ren) | |||||||||

| 0 Children | 861 (41.4) | 155 (35.2) | 0.019 | 767 (39.9) | 215 (35.8) | 0.070 | 713 (35.6) | 194 (37.2) | 0.469 |

| 1-10 Child(ren) | 1217 (58.5) | 283 (64.3) | 1155 (60.0) | 386 (64.2) | 1290 (64.3) | 326 (62.5) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | — | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | |||

| Type of cancer | |||||||||

| Bone, articular cartilage and soft tissues | 61 (2.9) | 11 (2.5) | n.a. | 53 (2.8) | 19 (3.2) | n.a. | 49 (2.4) | 23 (4.4) | n.a. |

| Breast | 420 (20.2) | 87 (19.8) | 371 (19.3) | 137 (22.8) | 373 (18.6) | 135 (25.9) | |||

| Central nervous system | 57 (2.7) | 23 (5.2) | 47 (2.4) | 33 (5.5) | 35 (1.7) | 45 (8.6) | |||

| Digestive tract | 93 (4.5) | 25 (5.7) | 85 (4.4) | 35 (5.8) | 98 (4.9) | 22 (4.2) | |||

| Endocrine glands | 102 (4.9) | 22 (5.0) | 97 (5.0) | 27 (4.5) | 105 (5.2) | 19 (3.6) | |||

| Female genital organs | 156 (7.5) | 44 (10.0) | 144 (7.5) | 56 (9.3) | 150 (7.5) | 51 (9.8) | |||

| Hematological malignancies | 270 (13.0) | 66 (15.0) | 232 (12.1) | 106 (17.6) | 257 (12.8) | 82 (15.7) | |||

| Head and neck | 36 (1.7) | 9 (2.0) | 33 (1.7) | 12 (2.0) | 31 (1.5) | 14 (2.7) | |||

| Male genital organs | 370 (17.8) | 74 (16.8) | 356 (18.5) | 88 (14.6) | 389 (19.4) | 55 (10.5) | |||

| Respiratory tract | 14 (0.7) | 9 (2.0) | 12 (0.6) | 11 (1.8) | 13 (0.6) | 10 (1.9) | |||

| Skin | 451 (21.7) | 59 (13.4) | 448 (23.3) | 62 (10.3) | 456 (22.7) | 54 (10.3) | |||

| Urinary tract | 41 (2.0) | 9 (2.0) | 39 (2.0) | 12 (2.0) | 42 (2.1) | 9 (1.7) | |||

| Other/unspecified sitesh | 8 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 7 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 7 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | |||

| Type of hospital of treatment | |||||||||

| University hospital | 519 (25.0) | 122 (27.7) | 0.227 | 464 (24.1) | 181 (30.1) | 0.003 | 486 (24.2) | 159 (30.5) | 0.004 |

| General/collaborating top clinical hospital or otheri | 1560 (75.0) | 318 (72.3) | 1460 (75.9) | 420 (69.9) | 1519 (75.8) | 363 (69.5) | |||

| Organ surgery | |||||||||

| No | 949 (45.6) | 195 (44.3) | 0.611 | 878 (45.6) | 269 (44.8) | 0.707 | 912 (45.5) | 236 (45.2) | 0.910 |

| Yes | 1130 (54.4) | 245 (55.7) | 1046 (54.4) | 332 (55.2) | 1093 (54.5) | 286 (54.8) | |||

| Local surgery | |||||||||

| No | 1463 (70.4) | 341 (77.5) | 0.003 | 1323 (68.8) | 487 (81.0) | <0.001 | 1409 (70.3) | 403 (77.2) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 616 (29.6) | 99 (22.5) | 601 (31.2) | 114 (19.0) | 596 (29.7) | 119 (22.8) | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 1219 (58.6) | 248 (56.4) | 0.380 | 1177 (61.2) | 293 (48.8) | <0.001 | 1228 (61.2) | 243 (46.6) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 860 (41.4) | 192 (43.6) | 747 (38.8) | 308 (51.2) | 777 (38.8) | 279 (53.4) | |||

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 1474 (70.9) | 302 (68.6) | 0.344 | 1398 (72.7) | 381 (63.4) | <0.001 | 1454 (72.5) | 327 (62.6) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 605 (29.1) | 138 (31.4) | 526 (27.3) | 220 (36.6) | 551 (27.5) | 195 (37.4) | |||

| Hormone therapy | |||||||||

| No | 1824 (87.7) | 380 (86.4) | 0.430 | 1700 (88.4) | 509 (84.7) | 0.018 | 1776 (88.6) | 435 (83.3) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 255 (12.3) | 60 (13.6) | 224 (11.6) | 92 (15.3) | 229 (11.4) | 87 (16.7) | |||

| Treatment received | |||||||||

| No | 46 (2.2) | 20 (4.5) | 0.005 | 43 (2.2) | 25 (4.2) | 0.011 | 47 (2.3) | 21 (4.0) | 0.035 |

| Yes | 2033 (97.8) | 420 (95.5) | 1881 (97.8) | 576 (95.8) | 1958 (97.7) | 501 (96.0) | |||

| Stagej | |||||||||

| I | 992 (60.0) | 179 (54.2) | 0.384 | 966 (62.4) | 206 (46.9) | <0.001 | 1009 (63.1) | 163 (41.9) | <0.001 |

| II | 364 (22.0) | 70 (21.2) | 323 (20.9) | 111 (25.3) | 331 (20.7) | 103 (26.5) | |||

| III | 163 (9.9) | 41 (12.4) | 147 (9.5) | 59 (13.4) | 155 (9.7) | 51 (13.1) | |||

| IV | 38 (2.3) | 8 (2.4) | 31 (2.0) | 16 (3.6) | 29 (1.8) | 18 (4.6) | |||

| Missing | 96 (5.8) | 32 (9.7) | 81 (5.2) | 47 (10.7) | 74 (4.6) | 54 (13.9) | |||

| Figo stagek | |||||||||

| I | 128 (82.1) | 34 (77.3) | — | 122 (84.7) | 39 (69.6) | — | 126 (84.0) | 36 (70.6) | — |

| II | 17 (10.9) | ≤10 | 13 (9.0) | 10 (17.9) | 15 (10.0) | ≤10 | |||

| III | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | |||

| IV | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | ≤10 | |||

| Ann Arbor stagel | |||||||||

| I | 27 (10.0) | ≤10 | — | 21 (9.1) | 13 (12.3) | — | 29 (11.3) | ≤10 | — |

| II | 77 (28.5) | 18 (27.3) | 70 (30.2) | 25 (23.6) | 79 (30.7) | 16 (19.5) | |||

| III | 29 (10.7) | ≤10 | 21 (9.1) | 10 (9.4) | 27 (10.5) | ≤10 | |||

| IV | 52 (19.3) | 10 (15.2) | 46 (19.8) | 17 (16.0) | 47 (18.3) | 16 (19.5) | |||

| Missing | 85 (31.5) | 29 (43.9) | 74 (31.9) | 41 (38.7) | 75 (29.2) | 41 (50.0) | |||

| Employee | |||||||||

| No | 198 (9.5) | — | n.a. | 209 (10.9) | — | n.a. | 255 (12.7) | — | n.a. |

| Yes | 1881 (90.5) | — | 1715 (89.1) | — | 1750 (87.3) | — | |||

| Self-employed | |||||||||

| No | 1881 (90.5) | — | n.a. | 1715 (89.1) | — | n.a. | 1750 (87.3) | — | n.a. |

| Yes | 198 (9.5) | — | 209 (10.9) | — | 255 (12.7) | — | |||

| Unemployment benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2042 (98.2) | 384 (87.3) | <0.001 | 1900 (98.8) | 570 (94.8) | <0.001 | 1976 (98.6) | 496 (95.0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 37 (1.8) | 56 (12.7) | 24 (1.2) | 31 (5.2) | 29 (1.4) | 26 (5.0) | |||

| Social assistance benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2069 (99.5) | 378 (85.9) | <0.001 | 1912 (99.4) | 498 (82.9) | <0.001 | 1995 (99.5) | 429 (82.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 10 (0.5) | 62 (14.1) | 12 (0.6) | 103 (17.1) | 10 (0.5) | 93 (17.8) | |||

| Social security benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2055 (98.8) | 383 (87.0) | <0.001 | 1883 (97.9) | 544 (90.5) | <0.001 | 1971 (98.3) | 450 (86.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 24 (1.2) | 57 (13.0) | 41 (2.1) | 57 (9.5) | 34 (1.7) | 72 (13.8) | |||

| Sickness/disability benefit | |||||||||

| No | 2060 (99.1) | 388 (88.2) | <0.001 | 1870 (97.2) | 406 (67.6) | <0.001 | 1921 (95.8) | 323 (61.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 19 (0.9) | 52 (11.8) | 54 (2.8) | 195 (32.4) | 84 (4.2) | 199 (38.1) | |||

| Student | |||||||||

| No | 1861 (89.5) | 336 (76.4) | <0.001 | 1796 (93.3) | 499 (83.0) | <0.001 | 1913 (95.4) | 488 (93.5) | 0.072 |

| Yes | 218 (10.5) | 104 (23.6) | 128 (6.7) | 102 (17.0) | 92 (4.6) | 34 (6.5) | |||

| Personal gross income [mean (SD)] | 38 431.45 (26 153.69) | 10 618.25 (10 087.29) | <0.001 | 41 300.21 (28 276.21) | 13 107.51 (13 604.81) | <0.001 | 48 551.31 (32 500.09) | 16 332.64 (13 790.74) | <0.001 |

| Economic independence of the person | |||||||||

| Not economically independent | 436 (21.0) | 395 (89.8) | <0.001 | 340 (17.7) | 548 (91.2) | <0.001 | 230 (11.5) | 474 (90.8) | <0.001 |

| Economically independent | 1639 (78.8) | 20 (4.5) | 1577 (82.0) | 33 (5.5) | 1769 (88.2) | 32 (6.1) | |||

| Missing | 4 (0.2) | 25 (5.7) | 7 (0.4) | 20 (3.3) | 6 (0.3) | 16 (3.1) | |||

| Indicator person with income | |||||||||

| Without personal income | ≤10% | 80 (18.2) | <0.001 | ≤10% | 94 (15.6) | <0.001 | ≤10% | 86 (16.5) | <0.001 |

| With personal income | ≥90% | 348 (79.1) | ≥90% | 500 (83.2) | ≥90% | 434 (83.1) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 12 (2.7) | 2 (0.1) | 7 (1.2) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | |||

| Gross household income [mean (SD)] | 79 121.89 (45 120.10) | 51 632.69 (50 778.12) | <0.001 | 85 712.75 (61 352.69) | 59 719.09 (68 212.80) | <0.001 | 99 471.44 (87 287.60) | 58 929.07 (45 060.78) | <0.001 |

| Benefit dependence of household | |||||||||

| No benefit dependence of household | 1542 (74.2) | 159 (36.1) | <0.001 | 1477 (76.8) | 163 (27.1) | <0.001 | 1601 (79.9) | 124 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Benefit dependence of household | 533 (25.6) | 256 (58.2) | 440 (22.9) | 418 (69.6) | 398 (19.9) | 382 (73.2) | |||

| Missing | 4 (0.2) | 25 (5.7) | 7 (0.4) | 20 (3.3) | 6 (0.3) | 16 (3.1) | |||

| Employees only | Baseline |

P value | One year after baseline (short-term) |

P value | Five years after baseline (long-term) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed AYAs (N = 1881) |

Unemployed AYAs (N = 0) |

Employed AYAs (N = 1715) |

Unemployed AYAs (N = 0) |

Employed AYAs (N = 1750) |

Unemployed AYAs (N = 0) |

||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Number of employment hours [mean (SD)] | 114.83 (43.31) | — | n.a. | 117.80 (43.60) | — | n.a. | 116.98 (39.32) | — | n.a. |

| Type of contract | |||||||||

| Fixed-term contract | 573 (30.5) | — | n.a. | 432 (25.2) | — | n.a. | 488 (27.9) | — | n.a. |

| Permanent contract | 1259 (66.9) | — | 1239 (72.2) | — | 1217 (69.5) | — | |||

| Both contract types | 36 (1.9) | — | 28 (1.6) | — | 26 (1.5) | — | |||

| Missing | 13 (0.7) | — | 16 (0.9) | — | 19 (1.1) | — | |||

| Employment | |||||||||

| Full time | 854 (45.4) | — | n.a. | 804 (46.9) | — | n.a. | 771 (44.1) | — | n.a. |

| Part time | 986 (52.4) | — | 879 (51.3) | — | 945 (54.0) | — | |||

| Both types of employment | 28 (1.5) | — | — | 16 (0.9) | — | — | 15 (0.9) | — | — |

| Missing | 13 (0.7) | — | 16 (0.9) | — | 19 (1.1) | — | |||

Independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests were carried out to compare AYA cancer survivors employed and unemployed.

AYA, adolescent and young adult; SD, standard deviation; n.a., not applicable due to low numbers.

Countries ≥1% are displayed.

Primary school, junior high school or equivalent.

Senior high school or equivalent.

College/university.

Institutional households, one-parent household or any other household than already included.

Member of institutional household, reference person in other household or any other member than already included.

Member of the household to whom the positions of the other members of the household are determined.

Unspecified sites, primary sites unknown or unknown tumor type and eye.

For example general practitioner, freely established specialist or foreign hospital.

Figo and Ann Arbor stage were not included in the stage variable.

Gynecological malignancies.

Hematological malignancies.

For all time points, unemployed AYAs received significantly more often unemployment benefits, social assistance benefits, social security benefits and disability benefits compared with those employed (Table 3). Furthermore, unemployed AYAs were significantly less often economically independent compared with those employed: 4.5% versus 78.8% at baseline, 5.5% versus 82.0% 1 year after diagnosis and 6.1% versus 88.2% 5 years after baseline, respectively. Personal income was significantly less among those unemployed for all time points compared with employed AYAs. Also, unemployed AYAs were significantly more often studying compared with employed AYAs at baseline and 1 year later, however, this effect did not withstand 5 years later.

On a household level, the income was on average significantly higher of employed AYAs compared with those unemployed for all time points. At baseline, 58.2% of the households of those unemployed were dependent on receiving benefits, compared with 25.6% of the households of those employed. This significant difference increased 1 year later (69.6% versus 22.9%) and 5 years later (73.2% versus 19.9%).

Factors associated with employment

Results of the logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 4. Among the AYAs, employment in the short-term was associated with being of older age and having completed middle- or high-level education. In the long-term, being employed was associated with not having a partner, having completed middle- or high-level education, one’s place in a household and being the reference person of a household. Clinical factors associated with unemployment include a cancer diagnosis of the central nervous system (CNS) (short- and long-term) and being treated with chemotherapy (long-term).

Table 4.

Logistic regression models evaluating factors associated with short- and long-term employment

| One year after baseline (short-term) |

Five years after baseline (long-term) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regression |

Univariable logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regression |

|||||

| Nagelkerkes R2 = 0.253 |

Nagelkerkes R2 = 0.276 |

|||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 0.85 (0.705-1.025) | 0.089 | 0.801 (0.538-1.194) |

0.276 | 0.564 (0.46-0.692) |

<0.001 | 0.653 (0.404-1.054) |

0.081 |

| Age | 1.065 (1.048-1.082) |

<0.001 | 1.029 (1.002-1.057) |

0.033 | 1.011 (0.994-1.028) |

0.214 | —k | — |

| Country of birth | ||||||||

| Netherlands | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Other | 0.381 (0.294-0.494) |

<0.001 | 1.289 (0.375-4.431) |

0.687 | 0.342 (0.263-0.445) |

<0.001 | 0.743 (0.228-2.424) |

0.623 |

| Generation | ||||||||

| Native | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| First-generation immigrant | 0.309 (0.235-0.406) |

<0.001 | 0.401 (0.112-1.441) |

0.161 | 0.289 (0.219-0.381) |

<0.001 | 0.772 (0.226-2.629) |

0.678 |

| Second-generation immigrant | 0.432 (0.328-0.57) |

<0.001 | 0.524 (0.373-0.737) |

<0.001 | 0.419 (0.314-0.558) |

<0.001 | 0.526 (0.355-0.759) |

0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Partner | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No partner | 0.634 (0.521-0.772) |

<0.001 | 1.003 (0.710-1.416) |

0.987 | 0.803 (0.661-0.977) |

0.028 | 1.544 (1.077-2.213) |

0.018 |

| Educational level (achieved) | ||||||||

| Lowa | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Middleb | 2.088 (1.604-2.719) |

<0.001 | 1.75 (1.148-2.669) |

0.009 | 2.74 (2.068-3.631) |

<0.001 | 2.519 (1.818-3.49) |

<0.001 |

| Highc | 6.683 (4.958-9.009) |

<0.001 | 5.467 (3.137-9.529) |

<0.001 | 7.328 (5.388-9.967) |

<0.001 | 6.13 (4.295-8.75) |

<0.001 |

| Educational level (followed) | ||||||||

| Lowa | Reference | Reference | Reference | Referencel | ||||

| Middleb | 2.43 (1.731-3.412) |

<0.001 | 1.308 (0.789-2.169) |

0.298 | 3.206 (2.276-4.517) |

<0.001 | — | — |

| Highc | 5.136 (3.672-7.184) |

<0.001 | 1.061 (0.573-1.965) |

0.851 | 7.668 (5.441-10.806) |

<0.001 | — | — |

| Type of household | ||||||||

| Single person | Reference | Reference | Reference | Referencel | ||||

| Couple without children | 1.936 (1.401-2.676) |

<0.001 | 0.401 (0.023-7.026) |

0.531 | 1.716 (1.229-2.395) |

0.002 | — | — |

| Couple with children | 1.172 (0.916-1.5) |

0.208 | 0.306 (0.097-0.965) |

0.043 | 1.579 (1.215-2.054) |

0.001 | — | — |

| Otherd | 0.427 (0.302-0.602) |

<0.001 | 0.503 (0.195-1.295) |

0.154 | 0.477 (0.338-0.674) |

<0.001 | — | — |

| Place in household | ||||||||

| Single | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Child living at home | 0.514 (0.379-0.697) |

<0.001 | 3.349 (0.307-36.555) |

0.322 | 0.77 (0.522-1.134) |

0.186 | 2.564 (1.181-5.566) |

0.017 |

| Partner without children | 1.957 (1.415-2.708) |

<0.001 | 5.510 (0.319-95.046) |

0.240 | 1.711 (1.226-2.389) |

0.002 | 3.616 (2.115-6.183) |

<0.001 |

| Partner with children | 1.563 (1.203-2.031) |

0.001 | 5.777 (0.533-62.586) |

0.149 | 1.735 (1.325-2.27) |

<0.001 | 4.697 (2.718-8.119) |

<0.001 |

| Parent in one-parent household | 0.418 (0.268-0.652) |

<0.001 | 1.050 (0.081-13.538) |

0.970 | 0.468 (0.315-0.695) |

<0.001 | 0.634 (0.374-1.074) |

0.09 |

| Othere | 0.237 (0.128-0.441) |

<0.001 | — | — | 0.433 (0.232-0.809) |

0.009 | 2.03 (0.774-5.32) |

0.15 |

| Reference person of household | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.351 (1.121-1.628) |

0.002 | 1.418 (0.88-2.285) |

0.152 | 1.326 (1.091-1.61) |

0.004 | 2.382 (1.384-4.099) |

0.002 |

| Number of persons in household who are living-at-home child(ren) | ||||||||

| 0 children | Reference | Reference | Reference | Referencej | ||||

| 1-10 child(ren) | 0.839 (0.694-1.014) |

0.07 | 1.119 (0.083-15.011) |

0.932 | 1.077 (0.882-1.315) |

0.469 | — | — |

| Type of cancer | ||||||||

| Breast | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Digestive tract | 0.897 (0.578-1.392) |

0.627 | 0.628 (0.311-1.265) |

0.192 | 1.612 (0.9750-2.665) |

0.063 | 1.507 (0.675-3.364) |

0.317 |

| Respiratory tract | 0.403 (0.174-0.934) |

0.034 | 0.414 (0.126-1.357) |

0.146 | 0.471 (0.202-1.098) |

0.081 | 0.377 (0.114-1.244) |

0.109 |

| Skin | 2.668 (1.918-3.712) |

<0.001 | 1.25 (0.573-2.727) |

0.575 | 3.056 (2.167-4.311) |

<0.001 | 1.823 (0.814-4.082) |

0.144 |

| Bone, articular cartilage and soft tissues | 1.03 (0.589-1.802) |

0.917 | 0.95 (0.389-2.322) |

0.910 | 0.771 (0.452-1.314) |

0.339 | 0.5 (0.2-1.248) |

0.138 |

| Head and neck | 1.015 (0.51-2.023) |

0.965 | 1.183 (0.448-3.124) |

0.734 | 0.801 (0.414-1.552) |

0.512 | 0.467 (0.177-1.233) |

0.124 |

| Female genital organs | 0.95 (0.659-1.369) |

0.781 | 0.787 (0.432-1.433) |

0.433 | 1.065 (0.733-1.547) |

0.743 | 1.075 (0.578-1.999) |

0.819 |

| Male genital organs | 1.494 (1.102-2.026) |

0.010 | 0.898 (0.474-1.702) |

0.742 | 2.56 (1.814-3.612) |

<0.001 | 0.953 (0.478-1.899) |

0.891 |

| Urinary tract | 1.2 (0.61-2.36) |

0.597 | 1.144 (0.423-3.089) |

0.791 | 1.689 (0.801-3.563) |

0.169 | 0.754 (0.274-2.078) |

0.585 |

| Hematological malignancies | 0.808 (0.598-1.093) |

0.167 | 0.694 (0.388-1.242) |

0.219 | 1.134 (0.826-1.558) |

0.436 | 0.97 (0.531-1.771) |

0.92 |

| Endocrine glands | 1.327 (0.83-2.121) |

0.238 | 1.482 (0.715-3.073) |

0.29 | 2 (1.181-3.387) |

0.010 | 1.202 (0.548-2.634) |

0.647 |

| Central nervous system | 0.526 (0.323-0.855) |

0.010 | 0.39 (0.17-0.895) |

0.026 | 0.282 (0.174-0.457) |

<0.001 | 0.147 (0.061-0.352) |

<0.001 |

| Otherf | 0.862 (0.22-3.379) |

0.831 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.845 (0.215-3.313) |

0.809 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Type of hospital of treatment | ||||||||

| University hospital | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| General hospital | 1.247 (0.98-1.585) |

0.072 | 0.97 (0.696-1.353) |

0.859 | 1.391 (1.077-1.796) |

0.011 | 0.95 (0.659-1.368) |

0.781 |

| Collaborating top clinical hospital | 1.369 (1.095-1.712) |

0.006 | 1.198 (0.881-1.629) |

0.249 | 1.33 (1.053-1.679) |

0.016 | 0.95 (0.679-1.33) |

0.765 |

| Otherg | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 2.421 (0.935-6.266) |

0.068 | 0.388 (0.128-1.174) |

0.094 |

| Organ surgery | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Referencej | Reference | Referencej | ||||

| Yes | 0.965 (0.803-1.16) |

0.707 | — | — | 0.989 (0.815-1.2) |

0.91 | — | — |

| Local surgery | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.941 (1.549-2.432) |

<0.001 | 1.299 (0.751-2.248) |

0.349 | 1.432 (1.143-1.795) |

0.002 | 0.79 (0.447-1.398) |

0.418 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.604 (0.502-0.726) |

<0.001 | 0.836 (0.574-1.218) |

0.351 | 0.551 (0.454-0.669) |

<0.001 | 0.539 (0.356-0.817) |

0.004 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.652 (0.537-0.791) |

<0.001 | 0.739 (0.543-1.005) |

0.054 | 0.635 (0.519-0.778) |

<0.001 | 1.028 (0.74-1.427) |

0.870 |

| Hormone therapy | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.729 (0.561-0.947) |

0.018 | 0.938 (0.581-1.516) |

0.794 | 0.645 (0.493-0.843) |

0.001 | 1.282 (0.783-2.092) |

0.319 |

| Immunotherapy | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | n.s. | n.s. | — | — | n.s. | n.s. | — | — |

| Treatment received | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.899 (1.15-3.136) |

0.012 | 1.264 (0.554-2.885) |

0.578 | 1.746 (1.034-2.948) |

0.037 | 1.402 (0.543-3.621) |

0.485 |

| Stageh | ||||||||

| I | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| II | 0.621 (0.477-0.807) |

<0.001 | 0.975 (0.672-1.416) |

0.895 | 0.519 (0.394-0.684) |

<0.001 | 0.982 (0.658-1.464) |

0.927 |

| III | 0.531 (0.379-0.745) |

<0.001 | 0.867 (0.533-1.41) |

0.565 | 0.491 (0.344-0.702) |

<0.001 | 0.904 (0.537-1.522) |

0.703 |

| IV | 0.413 (0.222-0.769) |

0.005 | 0.700 (0.31-1.579) |

0.390 | 0.26 (0.141-0.479) |

<0.001 | 0.438 (0.186-1.031) |

0.059 |

| Figo stagei | ||||||||

| I | Reference | Referencej | Reference | Referencej | ||||

| II | 0.416 (0.169-1.022) |

0.056 | — | — | 0.536 (0.21-1.364) |

0.191 | — | — |

| III | 0.373 (0.118-1.176) |

0.092 | — | — | 0.333 (0.105-1.054) |

0.062 | — | — |

| IV | 0.639 (0.056-7.243) |

0.718 | — | — | 0.571 (0.05-6.483) |

0.652 | — | — |

| Ann Arbor stagej | ||||||||

| I | Reference | Referencej | Reference | Referencej | ||||

| II | 1.733 (0.757-3.97) |

0.193 | — | — | 0.851 (0.286-2.534) |

0.772 | — | — |

| III | 1.3 (0.468-3.614) |

0.615 | — | — | 1.164 (0.283-4.793) |

0.834 | — | — |

| IV | 1.675 (0.69-4.069) |

0.255 | — | — | 0.506 (0.168-1.53) |

0.228 | — | — |

Univariable: P < 0.1 is included in multivariable analyses. Multivariable: P < 0.05 is significant. Method = enter. Tolerance (value <0.1 indicates multi-collinearity), variance inflation factors (value >10 indicates multi-collinearity) and variance proportions (proportions on the same eigenvalue ≥0.7 indicate multi-collinearity) were checked for multi-collinearity.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; n.s., not specified due to low numbers.

Primary school, junior high school or equivalent.

Senior high school or equivalent.

College/university.

Institutional households, one-parent household or any other household than already included.

Member of institutional household, reference person in other household or any other member than already included.

Unspecified sites, primary sites unknown or unknown tumor type and eye.

For example general practitioner, freely established specialist or foreign hospital.

Figo and Ann Arbor stage were included as a separate category in order to include all tumor types, but are not reported.

Gynecological malignancies.

Hematological malignancies.

Variables were excluded from multivariable analysis due to univariable analysis P > 0.1.

Variables were excluded from multivariable analysis due to multi-collinearity.

Discussion

Findings

This nationwide, population-based case-control registry study showed that AYA cancer survivors are significantly less often employed 1 and 5 years after diagnosis compared with an age- and sex-matched control population. Also, AYA cancer survivors received significantly more often disability benefits compared with controls both short and long-term. Personal and household income, however, did not significantly differ between these groups. Females were significantly more often unemployed in the long-term compared with males. Unemployed AYAs received significantly more often unemployment benefits, social assistance benefits, social security benefits and disability benefits compared with employed AYAs. Unfortunately, receiving these benefits does not compensate for differences in income: personal income was on average significantly higher among those employed for all time points compared with those unemployed. Similarly, employed AYAs were significantly more often economically independent. The results of this study are consistent with other international studies among AYA cancer survivors that show affected employment and financial outcomes.16,27,28,32,37,38

This study adds to the current knowledge by showing significantly decreased levels of employed AYAs compared with matched controls based on objective, registry-based data, both short- and long-term. The percentage of unemployed AYAs significantly increases from baseline (17.4%) to 1 year later (23.8%) and still remains increased 5 years after diagnosis (20.7%). This is in line with the study of Sisk and colleagues,28 showing increasing percentages of unemployed AYAs after their diagnosis over time and Dahl and colleagues38 who show a long-term (≥6 years since first cancer diagnosis) reduction in work ability among Norwegian young adult cancer survivors. Guy and colleagues20 also reported significant differences between AYAs and controls: 33.4% of the AYA cancer survivors were not employed versus 27.4% of the controls. Differences in results may be explained by self-reported versus objective data, types of employment included (i.e. employees and/or self-employed) and worldwide differences in health care and social security systems.39 Although childhood and older adult cancer survivors may also experience poor work-related outcomes, study results may not be directly comparable due to differences between populations (e.g. age at diagnosis, tumor types and related treatments, different long-term and late effects, no versus limited versus extensive work experience, and one of the first jobs versus close to retirement).9,40,41

The study of Teckle and colleagues32 among young Canadian cancer survivors indicates that AYAs may face lower income than their peers. In our study, personal and household income did not differ between the AYAs and controls, even though differences in employment were observed. This may be explained by the set of available benefits (disability, unemployment, social welfare, social security) for which one can apply in the Netherlands that may (partly) compensate for the lost income from employment.42 The income variables used in this study consist of, among others, income from employment as well as received benefits. This would indicate that the Dutch social support system does help AYAs well with keeping a stable income. When zooming into (un)employed AYAs, however, significant differences were seen in income even when benefits were provided. This indicates there is also a group of survivors who may not be employed because of the effects of cancer (treatment) and who have to get by with significantly less income: available financial benefits do not fully cover the difference. This, in combination with possibly having high medical costs and less financial reserves,16,20 may have a (long-term) financial impact on AYAs. Which factors are associated with AYAs’ financial outcomes and how this may change over time is currently being explored. In addition, it is important to have a closer look at which AYAs are staying behind and how to best provide support. It should be noted that a larger part of the unemployed AYA cancer population is studying compared with those employed short-term, which may partly explain differences in income. This is in line with literature showing that many AYAs face educational disruptions and perhaps have to change their educational goals, leading to many AYAs still studying.6,18,43

Based on treatment data, results showed that unemployed AYA cancer survivors 1 and 5 years after diagnosis were more often treated with systemic treatments (i.e. chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy). This indicates that a heavier treatment burden may significantly impact employment outcomes, also in the long-term. These findings are in line with the study of Dahl and colleagues,38 where both low work ability and non-employment were associated with heavier treatment burden. This result was not observed within our multivariable logistic regression analyses, however, except for chemotherapy. A cancer diagnosis of the CNS was also associated with both short- and long-term unemployment. This is in line with results of other studies and can be explained by the cognitive and/or physical problems often experienced by CNS cancer survivors.19,44

Findings of this study also indicate an impact on household level, reinforcing current knowledge that not only the AYA cancer survivor him/herself is impacted, but also their close ones. Ketterl and colleagues37 showed that some families borrow money, incur debt or even file for bankruptcy because of the cancer (treatment), which negatively affects their prospects. To what extent this takes place may differ per country and health care system. Future research should assess the degree of impact of an AYA cancer diagnosis on a household level.

As the current study included objective, population-based registry data only, we do not know any specific reasoning for unemployment based on patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Some AYAs may be forced due to the adverse effects of their cancer (treatment) or may face employment-related discrimination, whereas others may deliberately choose to change their employment status, because of their changed perspective on life and employment due to their experience.18,27,37,38,45 So far, less is known about how often AYAs face employment-related discrimination.27 Fortunately, there is also a group of AYAs who are doing well: they do not experience any objective work and financial issues. It is unknown, however, whether they made use of support systems, like AYA-specific health care for example. Furthermore, although their objective outcomes are good, it can be the case that these AYAs still experience subjective work and financial issues not captured by objective measures. Further research, in which objective data and PROs are combined, is needed to evaluate the objective study results in light of the personal situation and perspective of the AYA him/herself.

Strengths and limitations

Many studies carried out in the past have used self-reported data only, possibly leading to biased results. Our study’s strength is the use of objective, nationwide, population-based registry data. Also, the inclusion of a control population made it possible to compare employment and financial outcomes with age- and sex-matched controls, which has been done only to a limited extent up until now.32 In addition, whereas many studies focus on one invasive tumor type or a subset of invasive tumor types, in this study all invasive tumor types were included improving the generalizability of the results.

A limitation may be that the inclusion criteria for the cancer survivor sample were not exactly the same as for the controls. AYAs had to be alive for 5 years after diagnosis to be included, whereas the controls had to be living in the Netherlands with a known source of income for the same span of 5 years in order to be included (i.e. prevent inclusion from those emigrating). Comparable choices were made in the study of de Wind and colleagues46 who argue, however, that this has most likely not impacted study results. Secondly, of all AYAs, 4.4% could not be linked with their CBS ID. Significant differences were seen between AYAs who were linked with their CBS ID and those not linked, regarding age, several therapies and the type of hospital of treatment. As it concerns only a very small percentage of the total population, however, we do not expect major differences regarding employment and financial outcomes. Also, what the effects are of new treatments, including immunotherapy and targeted therapy, are unknown as this study was done in a population where these therapies have largely not yet been introduced. Lastly, as mentioned earlier, we have no subjective data that may help interpreting current objective results based on AYAs’ cancer experience.

Recommendations for further research and practice

Taking into account the results of this study, future research is needed that combines objective data and PROs to understand the self-reported reasons for the (objective) employment and financial outcomes, especially for those at risk of decreased income levels, economic dependence and unemployment, and what we can learn from those who do not experience any issues. As an extension, relatives/households could be part of these studies as well, since the effect of a diagnosis is not limited to the patient him/herself. Also, gaining knowledge about how to best help those at increased risk of adverse outcomes with supportive, age-specific interventions (i.e. type of support, time wise, involvement of stakeholders like clinical occupational physicians, available tools and resources) may help improving AYA cancer survivorship outcomes. These interventions should be incorporated into AYA programs, focusing on age-specific instead of tumor-specific aspects. The entire population of AYAs should be taken into account as issues and rationales may differ—e.g. those with an uncertain or poor prognosis may value employment as much as those diagnosed with a lower stage. Study results provide input for developing AYA-specific practical interventions that are part of standard AYA survivorship care, including creating awareness and knowledge of possible short- and long-term disease-related effects, providing education and structured guidance and the availability of resources and support. To properly embed all of this, both guidelines and policies must be drawn up to guarantee the existence and quality of AYA specific survivorship care focusing on employment and financial outcomes.

Conclusion

Using objective, nationwide, population-based registry data, the results of this study show that AYA cancer survivors are more often unemployed compared with age- and sex-matched controls, up to at least 5 years after diagnosis. Although financial benefits are widely available, those unemployed have a significantly lower income than employed AYAs. Therefore, actions should be taken to address the employment and financial outcomes of AYA cancer survivors at the level of cancer care institutions proactively providing tailored cancer survivorship care, as well as on a macro system level where policies and programs should be developed. Providing support regarding employment and financial outcomes from diagnosis onwards may help AYAs finding their way (back) into society.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), for the collection and their permission to use the demographic and clinical data of the AYA cancer survivors. The authors would like to thank Statistics Netherlands (CBS) as well, for the collection and their permission to use the demographic data and data regarding employment and finances of all AYAs and controls.

Funding

This work was supported by an infrastructural grant from the Dutch Cancer Society [grant number 11788 COMPRAYA study], a VIDI grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research [grant number VIDI198.007] and Janssen-Cilag B.V.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing

Restrictions apply to the availability of the NCR and CBS data described in this paper. Both parties need to give permission to access the data.

Ethics

Ethical review and approval were waived. NCR and CBS data are collected for registration purposes. The NCR and CBS both reviewed and approved the study protocols.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Close A.G., Dreyzin A., Miller K.D., Seynnaeve B.K.N., Rapkin L.B. Adolescent and young adult oncology—past, present, and future. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):485–496. doi: 10.3322/caac.21585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Meer D.J., Karim-Kos H.E., van der Mark M., et al. Incidence, survival, and mortality trends of cancers diagnosed in adolescents and young adults (15–39 years): a population-based study in the Netherlands 1990–2016. Cancers. 2020;12(11):3421. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Review Group . USA National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2006. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirchhoff A.C., Spraker-Perlman H.L., McFadden M., et al. Sociodemographic disparities in quality of life for survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3(2):66–74. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2013.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonorezos E.S., Oeffinger K.C. Research challenges in adolescent and young adult cancer survivor research. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2295–2300. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellizzi K.M., Smith A., Schmidt S., et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118(20):5155–5162. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zebrack B.J. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2289–2294. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidler M.M., Frobisher C., Hawkins M.M., Nathan P.C. Challenges and opportunities in the care of survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(6) doi: 10.1002/pbc.27668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen S.H., van der Graaf W.T.A., van der Meer D.J., Manten-Horst E., Husson O. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivorship practices: an overview. Cancers. 2021;13(19):4847. doi: 10.3390/cancers13194847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamminga S.J., de Boer A.G., Verbeek J.H., Frings-Dresen M.H. Breast cancer survivors’ views of factors that influence the return-to-work process-a qualitative study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38:144–154. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiedtke C., de Rijk A., Dierckx de Casterlé B., Christiaens M.R., Donceel P. Experiences and concerns about ‘returning to work’ for women breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):677–683. doi: 10.1002/pon.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mols F., Vingerhoets A.J., Coebergh J.W., van de Poll-Franse L.V. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(17):2613–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells M., Williams B., Firnigl D., et al. Supporting ‘work-related goals’ rather than ‘return to work’ after cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of 25 qualitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22(6):1208–1219. doi: 10.1002/pon.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearce A., Tomalin B., Kaambwa B., et al. Financial toxicity is more than costs of care: the relationship between employment and financial toxicity in long-term cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brock H., Friedrich M., Sender A., et al. Work ability and cognitive impairments in young adult cancer patients: associated factors and changes over time—results from the AYA-Leipzig study. J Cancer Surviv. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leuteritz K., Friedrich M., Sender A., et al. Return to work and employment situation of young adult cancer survivors: results from the Adolescent and Young Adult-Leipzig Study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2021;10(2):226–233. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2020.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsons H.M., Harlan L.C., Lynch C.F., et al. Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2393–2400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vetsch J., Wakefield C.E., McGill B.C., et al. Educational and vocational goal disruption in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27(2):532–538. doi: 10.1002/pon.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77(2):109–130. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy G.P., Jr., Yabroff K.R., Ekwueme D.U., et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff. 2014;33(6):1024–1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tai E., Lunsford N.B., Townsend J., Fairley T.L., Moore A., Richardson L.C. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(19):4884–4891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grinyer A. The biographical impact of teenage and adolescent cancer. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(4):265–277. doi: 10.1177/1742395307085335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fardell J.E., Wakefield C.E., Patterson P., et al. Narrative review of the educational, vocational, and financial needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: recommendations for support and research. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7(2):143–147. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone D.S., Ganz P.A., Pavlish C., Robbins W.A. Young adult cancer survivors and work: a systematic review. J Cancer Survivorship. 2017;11(6):765–781. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0614-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]