Abstract

A hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase-targeted fluorescent biosensor enables the early diagnostics of abiotic stresses in plants.

Dear Editor,

Presently, about 10% of the global population experience starvation. The situation has worsened with the growing population and the effect of Covid-19 (Laborde et al., 2020). Therefore, developing agriculture science and technology is vital for the society. Abiotic stresses (drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and so on) threaten plant growth. Thus, methods for monitoring plant abiotic stress in time are extremely important for agricultural production (Li et al., 2021). Currently, many technologies that can detect plant abiotic stress are destructive and need laborious sample preparation (Zhu, 2016). Optical sensing technologies can achieve rapid and noninvasive abiotic stress diagnosis in vivo. However, these optical sensing techniques, such as Red Green Blue (RGB) imaging (Bai et al., 2018), multispectral imaging (Zaman-Allah et al., 2015), hyperspectral imaging (Susič et al., 2018), chlorophyll fluorescence imaging (Kalaji et al., 2016), thermal infrared imaging (Prashar and Jones, 2016), and Raman spectroscopy (Altangerel et al., 2017), provide limited information about physical parameters, and few have been used for early diagnostics. Thus, development of a generic high-throughput phenotyping platform capable of easy and noninvasive biochemical sensing is valuable for precise early response detection. To fill this gap, we report the rational design of fluorescent biosensor targeting 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD), and the design rationale was validated by the co-crystallization of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) HPPD (AtHPPD) complexed with the probe. The probe is capable of noninvasive and nondestructive in situ real-time fluorescence imaging of HPPD in plants subjected to various abiotic stresses. Consequently, we demonstrate that the developed biosensor holds promise for future development of high-throughput screening for plant phenotyping and the diagnosis of numerous abiotic stresses.

HPPD plays a vital role in the biosynthesis of important plant metabolites such as vitamin E and plastoquinone (Moran, 2005; Schneider, 2005; Lin et al., 2021), and is thus regarded as an important target in herbicide discovery (Beaudegnies et al., 2009; Santucci et al., 2017). Recently, a few studies found that HPPD is involved in abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated seed germination as well as abiotic stress tolerance (Falk et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2021), suggesting HPPD contributes to regulating plant stress response beyond its role in vitamin E biosynthesis. Thus, the development of an efficient tool for in situ real-time HPPD activity measurement in vivo is of great importance for in-depth understanding of physiological function and abiotic stress diagnosis in plants.

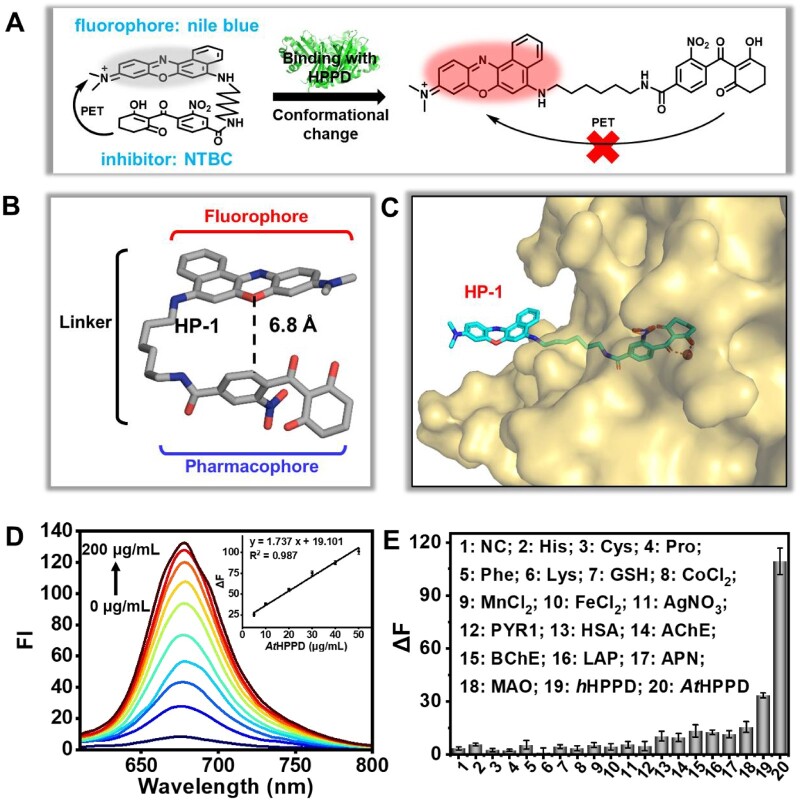

Inspired by previous investigations on the structural basis of HPPD inhibitors (López-Ramos and Perruccio, 2010; Lin et al., 2019), we proposed the mechanism-guided design of conformational changeable fluorescent probe targeting HPPD (Figure 1A). More specifically, we attached fluorophore at the aromatic moiety of pharmacophore nitisinone (also named NTBC) with an alkyl linker to build an inhibitor-based fluorescent HPPD probe (HP-1, Supplemental Figures S1–S12). Hopefully, the designed probe is in the folded state before binding with HPPD, thus fluorescence is quenched due to the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) effect of pharmacophore against the fluorophore. Upon binding with HPPD, the probe would unfold and the fluorescence will be restored because of the elimination of the PET effect. To validate the concept of the design rationale at the molecular level, the conformations of HP-1 before and after binding with HPPD were separately analyzed with quantum calculation and structure biology. The simulated conformer of HP-1 is in a folded state and the aromatic moiety of the pharmacophore is very close to the nile blue moiety (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, we determined the crystal structure of AtHPPD in complex with HP-1 at 2.0 Å resolution (Figure 1C; Supplemental S13). Final statistics for the crystal structure of AtHPPD harboring HP-1 are given in Supplemental Table S1 and was uploaded in protein data bank database (PDB code: 7VO8). To our delight, the nile blue moiety is located outside of the enzyme cavity and HP-1 is in a straight-line shape, which provides plausible evidence for the “off–on” fluorescence response upon binding with HPPD.

Figure 1.

Design rationale of the probe HP-1 and its sensing capability in vitro. A, The structure and mechanism of designed probe, HP-1. B, The lowest energy conformer of HP-1 without binding with HPPD (the distance between fluorophore and pharmacophore is about 6.8 Å). C, Crystallographic binding mode of HP-1 in AtHPPD. AtHPPD is shown in surface. HP-1 is indicated as cyan violet sticks. The metal ion is presented as ruby sphere ball. D, Fluorescence emission spectra of HP-1 (10 μM, λex = 580 nm) with the incubation of various concentrations (0–200 μg·mL−1) of AtHPPD at 37°C. The inset in (D) shows the linear relationship between the FI enhancement (ΔF) and the HPPD concentrations for LOD determination. The point of inset in (D) represents the mean of three replicates and the error bars indicate the standard error of mean (SEM). E, Specificity of HP-1 (λex = 580 nm, λem = 675 nm) towards various small molecules (1 mM) and proteins (10 μg·mL-1) at 37°C. Each bar represents the mean of three replicates and the error bars indicate the SEM. All the experiments in (D) and (E) were repeated at least three times.

Next, we characterized the optical property of HP-1. As expected, the fluorescence intensity (FI) of HP-1 indeed quench sharply in aqueous solution (100-mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), whereas produced about 16-fold enhancement upon incubation with AtHPPD (Figure 1D). The fluorescence of HP-1 increased with the growing solvent polarity (Supplemental Figure S14). In addition, the FI of HP-1 increased depending on the dosage of AtHPPD; the limit of detection (LOD) was 0.70 μg·mL−1. The specificity profile of HP-1 over other analytes was also investigated. The tested potential interfering species include some representative enzymes and proteins, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), leucine aminopeptidase (LAP), aminopeptidase N (APN), monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), pyrabactin resistance 1 (PYR1), human serum albumin (HSA), bovine serum albumin (BSA), some representative inorganic salts (CoCl2, MnCl2, FeCl2, and AgNO3), and amino acids (Pro, His, Cys, and GSH). HP-1 showed the best fluorescence response against HPPD, whereas other analytes caused no substantial interferences (Figure 1E). The excellent specificity and sensitivity in aqueous solution indicate the potential of HP-1 for sensing HPPD within complex biological samples.

Encouraged by the excellent performance of HP-1 in vitro, we further applied it to sense plant abiotic stresses. We performed the HP-1 based fluorescence imaging in plant models of Brassica napus L. and A.thaliana subjected to various abiotic stress conditions. Both plants were exposed to extreme conditions for 36 h, such as cold (4°C) stress, salt stress (100 mM NaCl), drought stress (30% PEG8000; Li et al., 2019), reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress (H2O2), or treatment with plant growth regulators (10 ppm gibberellins, 10 ppm ethephon, 100 μM ABA). Subsequently, they were treated with 10 μM HP-1 for 2 h, using the plants under normal condition as the negative control (NC) group. The fluorescence signal, particularly in the leaves, was then imaged and quantified (Figure 2, A–C; Supplemental Figure S15). Interestingly, enhanced fluorescence signal can be observed in various groups treated with ABA, H2O2, NaCl, PEG8000, ethephon, or cold temperature. While the FI of the group pretreated with commercial HPPD inhibitor mesotrione remarkably decreased. The endogenous level of HPPD in all samples was further verified by western blot analysis, which is consistent with the fluorescence imaging analysis (Supplemental Figure S16). In addition, mRNA levels of HPPD in Brassica napus L. under different abiotic stresses were also examined with quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Compared to NC group, the expression levels of HPPD of the treated groups were significantly increased (Figure 2D), which is consistent with the above fluorescence imaging and western blotting analysis, except for the gibberellins-treated group. In addition, ROS levels in the treated leaves of different groups were measured and the resultant data are shown in Figure 2E. Except for the NaCl-treated group, all the abiotic stresses triggered a remarkable increase in ROS, whereas inhibitor treatment did not cause significant increase of ROS compared with that of the NC group. Interestingly, the ROS level and HPPD activity in all the samples produced a linear regression curve with a correlation coefficient of about 0.88 (Figure 2F). These observations demonstrate that HPPD-based imaging with HP-1 could not only indicate physiological change but also suggest accumulation of ROS due to abiotic stresses. Besides, it shows that ROS may act as a bridge between abiotic stresses and HPPD, and the connection between HPPD, ROS, and abiotic stress deserves further study.

Figure 2.

Living image of Brassica napus L. by HP-1 after treating with and without inhibitor and various abiotic stresses. A, Schematic diagram of plant imaging process. B, Fluorescence image of Brassica napus L. treated with HP-1, after the preincubation without or with NaCl (100 mM), ABA (100 μM), H2O2 (100 mM), mesotrione (100 μM), 30% PEG8000, gibberellins (10 ppm), ethephon (10 ppm), or 4°C for 36 h before incubated with HP-1 (10 μM) for 2 h. C, Quantitative determination of fluorescence signal change of left part. D, Relative mRNA of HPPD in Brassica napus L. under different abiotic stresses. E, Quantitative determination of ROS level change of left part. F, Linear relationship between ROS level and HPPD activity in Brassica napus L. under different abiotic stresses. G, Fluorescence image of Brassica napus L. treated with HP-1 (10 μM) for 2 h in the presence of different concentrations of ABA (0 μM as NC, 100 μM, 200 μM, 500 μM, or 1 mM) for 36 h. H, Quantitative determination of fluorescence signal change in (G). I, Fluorescence image of Brassica napus L. treated with HP-1 (10 μM) for 2 h in the presence of 100 μM ABA for different times (0 h as NC, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h, 32 h, 40 h, or 48 h). J, Quantitative determination of fluorescence signal change in (I). K, Fluorescence image of Brassica napus L. treated with HP-1 (10 μM) for 2 h in the presence of different concentrations of NaCl (0 mM as NC, 50 mM, 100 mM, 200 mM, or 300 mM) for 24 h. L, Quantitative determination of fluorescence signal change in (K). M, Fluorescence image of Brassica napus L. treated with HP-1 (10 μM) for 2 h in the presence of 100-mM NaCl for different times (0 h as NC, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h, 32 h, 40 h, or 48 h). N, Quantitative determination of fluorescence signal change in (M). In (C, D, E, F, H, J, L, and N), each bar represents the mean of three replicates and the error bars indicate the standard error of mean (sem). All the experiments in (D) and (E) were repeated at least three times. Asterisks indicate significant differences between NC group and other groups. ns means no significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, statistical analyses were performed using an independent samples Dunnett’s test with equal variances, n = 3 independent experiments).

We further performed imaging of Brassica napus L. treated with different concentrations of two representative stress factors (ABA and NaCl). As expected, higher FI was observed by increasing the concentration of ABA and NaCl (Figure 2, G, H, K, and L). Moreover, the Brassica napus L. were imaged after they were pretreated by 100 μM ABA and 100 mM NaCl every 8 h for up to 48 h, respectively. It clearly shows that the FI of Brassica napus L. increased over time (Figure 2, I, J, M and N). These results demonstrate that our fluorometric method could qualitatively and quantitatively describe the early plant abiotic stresses in a nondestructive manner.

In conclusion, our study revealed a strategy of mechanism-based rational design of conformationally changeable fluorescent biosensor targeting HPPD, and identified HP-1 as an in situ fluorescent imaging tool for noninvasive or nondestructive detection of various abiotic stresses, including drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures. With this promising biosensor, we have developed a platform for in vivo diagnostics of early abiotic plant stress as well as ROS generation.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Materials and methods used in this research.

Supplemental Figure S1. Synthesis route and structure characteristics of HP-1 and intermediates.

Supplemental Figure S2. 1H NMR for compound 1 in chloroform-d.

Supplemental Figure S3. 13C NMR for compound 1 in chloroform-d.

Supplemental Figure S4. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum of for compound 1.

Supplemental Figure S5. 1H NMR for compound 2 in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S6. 13C NMR for compound 2 in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S7. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum of for compound 2.

Supplemental Figure S8. 1H NMR for compound 3 in CD3OD.

Supplemental Figure S9. 13C NMR for compound 3 in CD3OD.

Supplemental Figure S10. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum of for compound 3.

Supplemental Figure S11. HPLC analysis for probe HP-1.

Supplemental Figure S12. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum of for HP-1.

Supplemental Figure S13. The crystal structure of AtHPPD in complex with NTBC or HP-1, the calculation result of frontier molecular orbitals of HP-1, and the figures of structural characterization of HP-1 and the imaging results of HP-1 in A. thaliana.

Supplemental Figure S14. Fluorescence emission spectra of HP-1 in different polar solvents.

Supplemental Figure S15. Living imaging of A. thaliana treated with HP-1 in the absence and presence of various abiotic stresses.

Supplemental Figure S16. Western blot analysis of HPPD levels in Brassica napus L. treated with many abiotic stress factors.

Supplemental Table S1. Data collection and refinement statistics for the AtHPPD/HP-1 complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for providing the facility support.

Funding

We are grateful for the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1700103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21837001, 21977036 and U20A2038), and Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation (No. 2020BHB027).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Yi-Xuan Fu, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Shi-Yu Liu, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Wu-Yingzheng Guo, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Jin Dong, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Jia-Xu Nan, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Hong-Yan Lin, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Long-Can Mei, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Wen-Chao Yang, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Guang-Fu Yang, Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology of Ministry of Education, International Joint Research Center for Intelligent Biosensor Technology and Health, College of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, P.R. China.

Wet-laboratory experiments were performed by Y.X.F. (imaging study, data analysis and manuscript preparation), S.Y.L (synthesis of probe), W.Y.G (structural characterization of the probes), J.X.N. (preparation of intermediate for probe synthesis), J.D. (crystallization of HPPD with the probe), H.Y.L. (solved the crystal structure). LC.M. contributed the theoretical computation. W.C.Y. and G.F.Y. contributed to project design, preparation, and editing of the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Guang-Fu Yang (gfyang@mail.ccnu.edu.cn).

References

- Altangerel N, Ariunbold GO, Gorman C, Alkahtani MH, Borrego EJ, Bohlmeyer D, Hemmer P, Kolomiets M V., Yuan JS, Scully MO (2017) In vivo diagnostics of early abiotic plant stress response via Raman spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: 3393–3396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Jenkins S, Yuan W, Graef GL, Ge Y (2018) Field-based scoring of soybean iron deficiency chlorosis using RGB imaging and statistical learning. Front Plant Sci 9: 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudegnies R, Edmunds AJF, Fraser TEM, Hall RG, Hawkes TR, Mitchell G, Schaetzer J, Wendeborn S, Wibley J (2009) Herbicidal 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase inhibitors – A review of the triketone chemistry story from a Syngenta perspective. Bioorganic Med Chem 17: 4134–4152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk J, Krauß N, Dähnhardt D, Krupinska K (2002) The senescence associated gene of barley encoding 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase is expressed during oxidative stress. J Plant Physiol 159: 1245–1253 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Chen Z, Ban L, Wu Y, Huang J, Chu J, Fang S, Wang Z, Gao H, Wang X (2017) P-HYDROXYPHENYLPYRUVATE DIOXYGENASE from Medicago sativa is involved in Vitamin E biosynthesis and abscisic acid-mediated seed germination. Sci Rep 7: 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaji HM, Jajoo A, Oukarroum A, Brestic M, Zivcak M, Samborska IA, Cetner MD, Łukasik I, Goltsev V, Ladle RJ (2016) Chlorophyll a fluorescence as a tool to monitor physiological status of plants under abiotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol Plant 38: 102 [Google Scholar]

- Kim SE, Bian X, Lee CJ, Park SU, Lim YH, Kim BH, Park WS, Ahn MJ, Ji CY, Yu Y, et al. (2021) Overexpression of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (IbHPPD) increases abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic sweetpotato plants. Plant Physiol Biochem 167: 420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborde D, Martin W, Swinnen J, Vos R (2020) COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science 369: 500–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YB, Cui DZ, Sui XX, Huang C, Huang CY, Fan QQ, Chu XS (2019) Autophagic survival precedes programmed cell death in wheat seedlings exposed to drought stress. Int J Mol Sci 20: 5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhou J, Dong T, Xu Y, Shang Y (2021) Application of electrochemical methods for the detection of abiotic stress biomarkers in plants. Biosens Bioelectron 182: 113105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-Y, Chen X, Chen J-N, Wang D-W, Wu F-X, Lin S-Y, Zhan C-G, Wu J-W, Yang W-C, Yang G-F (2019) Crystal structure of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase in complex with substrate reveals a new starting point for herbicide discovery. Research 2019: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Chen X, Dong J, Yang JF, Xiao H, Ye Y, Li LH, Zhan CG, Yang WC, Yang GF (2021) Rational redesign of enzyme via the combination of quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics, molecular dynamics, and structural biology study. J Am Chem Soc 143: 15674–15687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Ramos M, Perruccio F (2010) HPPD: ligand- and target-based virtual screening on a herbicide target. J Chem Inf Model 50: 801–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran GR (2005) 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys 433: 117–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashar A, Jones H (2016) Assessing drought responses using thermal infrared imaging. Methods Mol Biol 1398: 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santucci A, Bernardini G, Braconi D, Petricci E, Manetti F (2017) 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase and its inhibition in plants and animals: small molecules as herbicides and agents for the treatment of human inherited diseases. J Med Chem 60: 4101–4125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C (2005) Chemistry and biology of vitamin E. Mol Nutr Food Res 49: 7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susič N, Žibrat U, Širca S, Strajnar P, Razinger J, Knapič M, Vončina A, Urek G, Gerič Stare B (2018) Discrimination between abiotic and biotic drought stress in tomatoes using hyperspectral imaging. Sens Actuator B Chem 273: 842–852 [Google Scholar]

- Zaman-Allah M, Vergara O, Araus JL, Tarekegne A, Magorokosho C, Zarco-Tejada PJ, Hornero A, Albà AH, Das B, Craufurd P, et al. (2015) Unmanned aerial platform-based multi-spectral imaging for field phenotyping of maize. Plant Methods 11: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK (2016) Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 167: 313–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.