Abstract

Objectives

We traced the historical arc of the rise in gray divorce (i.e., divorce that occurs among adults aged 50 and older) in the United States since 1970, elucidating unique patterns for middle-aged (aged 50–64) versus older (aged 65 and older) adults.

Methods

Data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 U.S. Vital Statistics Reports and the 2010 and 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) were used to chart the trends in gray divorce over the past half century. Drawing on the 2019 ACS, we estimated gray divorce rates across sociodemographic subgroups for today’s middle-aged and older adults. We pooled the 2010 (N = 757,835) and 2019 (N = 892,714) ACS data to assess whether divorce risks are shifting for middle-aged versus older adults.

Results

The gray divorce rate was low and grew only modestly between 1970 and 1990 before doubling by 2010. Since 2010, the rate has decreased slightly (but the decrease is not statistically significant). The gray divorce rate has stagnated among middle-aged adults but continues to climb among older adults.

Discussion

Our study illustrates the graying of divorce over the past half century. Nowadays, 36% of U.S. adults getting divorced are aged 50 or older. The only age group with an increasing divorce rate is adults aged 65 and older, raising new questions about how they will navigate old age.

Keywords: Baby Boomers, Gray divorce, Marital duration, Remarriage, Trends

Despite having one of the highest divorce rates in the world, the United States has witnessed a sustained, modest decline in its rate of divorce over the past four decades (Amato, 2010; Cohen, 2019). This overall trend belies growing divergence in divorce rates by age. Although divorce is falling among young adults, it has accelerated among middle-aged and older adults. In fact, adjusting for the aging of the population, the overall U.S. divorce rate has been rising (Kennedy & Ruggles, 2014), signaling the mounting salience of divorce in the second half of life.

Gray divorce, which is the term used by Brown and Lin (2012) to describe divorces that occur to adults aged 50 and older, doubled between 1990 and 2010. The gray divorce rate climbed from five divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons aged 50 and older in 1990 to 10 per 1,000 in 2010. This doubling of the gray divorce rate, coupled with the aging of the population, contributed to a dramatic shift in the composition of adults experiencing divorce. In 1990, fewer than one in ten (8%) persons getting divorced were aged 50 and older. By 2010, more than one in four (27%) people getting divorced were at least age 50.

This graying of divorce raises questions about both the historical arc of this trend and its contemporary contours. The trend in gray divorce prior to 1990 is unknown and whether gray divorce has shifted course since 2010 is also uncertain. Drawing on data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 U.S. Vital Statistics as well as the 2010 and 2019 American Community Survey (ACS), we chart the trend in the gray divorce rate over the past nearly half century (1970–2019), paying attention to whether and how the patterns differ for those in middle age (aged 50–64) and older adulthood (aged 65 and older). We also assess whether gray divorce has continued its ascent since 2010 and estimate the gray divorce rate for key sociodemographic subgroups of today’s middle-aged and older adults to provide a descriptive portrait of divorce during the second half of life. Finally, by pooling data from the 2010 and 2019 ACS, we aim to decipher whether the contours of the gray divorce phenomenon are changing, particularly in terms of the magnitude of the divorce risks experienced by middle-aged versus older adults. The findings from this study contribute to the growing literature on divorce in the second half of life by tracing the timing and tempo of the acceleration in gray divorce across the past five decades. Our work also sheds new light on the likely trajectory of the gray divorce trend in the coming years by elucidating whether and how current patterns are shifting among middle-aged versus older adults.

Background

Marital dissolution was once largely synonymous with widowhood among older adults. The rise in gray divorce means that older adult marital dissolutions are increasingly voluntary, occurring through divorce rather than widowhood (Carr & Utz, 2020). Among older women, about one-quarter of marital dissolutions are through divorce. For older men, a majority (52%) of marital dissolutions occur via divorce (Brown et al., 2018).

Explaining the Historical Rise in Gray Divorce

Scholars have long been attuned to the potential for growth in divorce during the second half of life (Berardo, 1982; Hammond & Muller, 1992; Ulhenberg & Myers, 1981; Uhlenberg et al., 1990). Not surprisingly, the emergence of this literature coincided with the divorce revolution that began in the 1970s and peaked in the early 1980s. The acceleration in divorce during this period was not confined to young adults but also appeared to be occurring among middle-aged and older adults, although empirical evidence was limited (Uhlenberg, 1990; Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981), underscoring the importance of tracing the historical arc of gray divorce.

Early researchers identified several broad factors that set the stage for growth in gray divorce during the 1970s and 1980s. First, the meaning of marriage and by extension marital success was changing as a growing emphasis on personal fulfillment and happiness gained prominence in concert with rising individualism (Berardo, 1982). Second, the norm of marriage as a lifelong union was eroding amidst record high divorce rates in the United States. Third, many adults were in remarriages, which were less stable than first marriages (Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981). Fourth, women’s growing financial autonomy made divorce more practicable when their marriage was unsatisfactory (Berardo, 1982; Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981). Finally, lengthening life expectancies meant increased exposure to the risk of divorce as the likelihood of widowhood at a given age diminished (Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981).

These leading indicators of a run-up in divorce among middle-aged and older adults likely contributed to the acceleration in gray divorce during the 1990–2010 period even as the overall U.S. divorce rate was attenuating. Theoretical treatises on older adult divorce during this era delineated how a fundamental shift in the meaning of marriage spanned all generations of society (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). Contemporary marriages have become individualized, with spouses emphasizing their own fulfillment and satisfaction (Cherlin, 2009). Those who once might have remained in empty shell (i.e., poor quality) marriages had become more willing to call it quits (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). In-depth interviews with gray-divorced adults revealed that growing apart in midlife was a common denominator across couples (Bair, 2007).

Relationship drift may be catalyzed by midlife role transitions that provide an opportunity for assessment of one’s marriage and life satisfaction more generally. Role transitions also can strain marriages, undermining marital stability. Couples busily engaged in rearing children and advancing in their careers may become unmoored when faced with an empty nest or retirement (Davey & Szinovacz, 2004; Hiedemann et al., 1998), although more recent work found no evidence that these life transitions were associated with the risk of gray divorce (Lin et al., 2018). A health decline, particularly for wives, also can be destabilizing for marriages (Karraker & Latham, 2015).

Researchers continue to speculate about the future of gray divorce. In their decade in review article on changing family demographics, Smock and Schwartz (2020) postulated a dampening of gray divorce as the age at marriage continues to rise and marriage is increasingly selective of economically advantaged, highly committed couples. This conjecture echoes Cohen’s (2019) assertion that declining divorce rates among younger adults may prevail as they age into the second half of life, leading to an attenuation in gray divorce. It also aligns with recent attitudinal research showing that younger adults hold less supportive toward divorce than do older adults, and this gap has widened over time (Brown & Wright, 2019). However, the share of adults aged 50 and older who are accepting of divorce as a solution to an unsatisfactory marriage rose from just over half in 1994 to two third in 2012, which Brown and Wright (2019) interpreted as consonant with continued growth in gray divorce. Although the trajectory of gray divorce since 2010 is uncertain, scholars agree that tracking this trend is an important next step (Carr & Utz, 2020), particularly given the aging of the married population (Smock & Schwartz, 2020). A recent review of the literature on divorce over the past decade underlined the growing salience of distinct patterns by age and pointed to the role of life course stage as “an important open question” for future research (Raley & Sweeney, 2020, p. 82).

Middle-Aged Versus Older Adults

The association between life course stage and the risk of gray divorce has shifted across time. Even though the divorce rate for older adults (aged 65 and older) trailed that of middle-aged (50–64) adults in both 1990 and 2010, the growth in the divorce rate over this time period was larger for older than middle-aged adults. Between 1990 and 2010, the older adult divorce rate nearly tripled whereas the divorce rate for middle-aged adults did not quite double (Brown & Lin, 2012). This shrinking gap in the risk of divorce for middle-aged versus older adults signals that the relationship between life course stage and gray divorce is mutable, a conclusion that is consistent with the well- established finding that some generations have faced higher risks of divorce at a given stage of the life course than others. For example, Baby Boomers, born in 1946–1964, were young adults during the divorce revolution of the 1970s and 1980s. Their risk of divorce during that time span was higher than that experienced by prior and subsequent generations of young adults (Cherlin, 1992; Cohen, 2019).

It is possible that the gray divorce phenomenon could be largely unique to the Baby Boomers (Raley & Sweeney, 2020). Their distinctive marital biographies, marked by exceptionally high levels of divorce and remarriage, presage elevated levels of gray divorce during the second half of life. Indeed, Baby Boomers composed the middle-aged group (50–64) in 2010 that exhibited the remarkably high rate of divorce dubbed “the gray divorce revolution” by Brown and Lin (2012). Unlike the Baby Boomers, subsequent generations (namely, Generation X, born 1965–1980) have come of age during an era of declining divorce and remarriage rates. First marriage has become increasingly selective of the most advantaged, contributing to the reduced risk of divorce during young adulthood over the past three decades (Cherlin, 2009; Cohen, 2019; Smock & Schwartz, 2020).

Although the middle-aged (aged 50–64) was composed entirely of Baby Boomers in 2010, by 2019 much of this generation had aged into older adulthood (aged 65 and older), with those in middle-age starting to be replaced by members of the succeeding generation, Generation X. This shift foretells a possible increase in the gray divorce rate for older adults, who are now primarily Baby Boomers. It also signals that the divorce rate for the middle-aged group may have stagnated or even declined as of 2019, given the lower divorce and remarriage rates earlier in the life course experienced by Generation X members.

The Present Study

Our study makes two important contributions to the growing literature on gray divorce. First, we establish the historical trend in gray divorce over the past half century. The doubling of the gray divorce rate between 1990 and 2010 is well-documented (Brown & Lin, 2012), but the arc of this trend prior to 1990 and since 2010 is unknown. By combining data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 U.S. Vital Statistics with the 2010 and 2019 ACS, we estimate the gray divorce rate for adults aged 50 and older as well as separately for those who are in middle age (aged 50–64) and older adulthood (aged 65 and older). We anticipate that gray divorce levels remained low from 1970 to 1990. National divorce statistics are not available for 2000 as the federal government discontinued the collection of divorce (and marriage) statistics from the states in the mid-1990s. With the introduction of marital history questions (including whether respondents got divorced in the past year) on the ACS to fill this critical gap in data on marriage and divorce incidence, we can tabulate estimates of the gray divorce rate for 2010 and 2019. We track whether the upward trend through 2010 persists, has stalled, or even reversed, providing new insights on how common divorce is among today’s middle-aged and older adults. We also estimate gray divorce rates across sociodemographic subgroups using the 2019 ACS data to elucidate the relative risks experienced by today’s middle-aged and older adults.

Second, we combine the 2010 and 2019 ACS data to assess whether the likelihood of gray divorce for middle-aged versus older adults has changed between 2010 and 2019. In 2010, middle-aged adults were more likely than older adults to divorce. This association may have diminished by 2019, reflecting the changing composition of these two age groups. Baby Boomers composed the middle-aged group in 2010, but as of 2019 many will have aged into the older adult group. Their uniquely high divorce rates across the adult life course, including the divorce revolution in the 1970s and 1980s when they were young adults and the gray divorce revolution when they were in middle age (50–64), suggest that the risk of divorce among older adults, who are now primarily Baby Boomers, may have increased between 2010 and 2019. Meanwhile, Generation X, a group that has experienced comparatively lower divorce and remarriage rates than Boomers, is advancing into midlife, and thus it is possible that gray divorce among middle-aged adults is stalling. In these analyses, we account for known correlates of gray divorce, including the marital biography (marriage order and marital duration), demographic characteristics (gender and race-ethnicity), and economic resources (education, employment, and income; Brown & Lin, 2012; Karraker & Latham, 2015; Lin et al., 2018). The marital biography is strongly related to gray divorce with those in marriages of longer duration less likely to divorce than those in shorter marriages. The risk of gray divorce is also higher for those in remarriages than first marriages. Interracial couples are at higher risk of gray divorce than are intraracial couples. Economic resources are protective against gray divorce.

Method

We drew on 1970, 1980, and 1990 U.S. Vital Statistics reports as well as 2010 and 2019 ACS data to chart the gray divorce rate over the 1970–2019 period. We also used the 2019 ACS data to estimate sociodemographic subgroup variation in gray divorce rates for today’s middle-aged and older adults. Finally, we combined the 2010 and 2019 ACS data to examine whether the association between age group and gray divorce differed between 2010 and 2019.

1970, 1980, and 1990 U.S. Vital Statistics Reports

The decennial marriage and divorce reports from the U.S. Vital Statistics for 1970, 1980, and 1990 each included the annual divorce rate and the number of divorces for men and women by five-year age group, permitting us to calculate an overall gray divorce rate (aged 50 and older) as well as divorce rates for middle-aged (aged 50–64) and older (aged 65 and older) adults. We first divided the number of divorced persons by the divorce rate to obtain the number of persons who were at risk of divorce. Then, we divided the sum of the numbers divorced across the age interval by the sum of the numbers divorced and the numbers at risk across the age interval as appropriate to obtain the divorce rate for a given age group.

Divorce statistics by five-year age group were only available from states in the Divorce Registration Area (DRA). In 1970, the DRA was composed of 28 states representing 61% of divorces nationwide (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 1974). In 1980, the DRA included 30 states that composed 49% of divorces that occurred in the United States that year (NCHS, 1985). In 1990, the DRA included 31 states (two of which did not report the ages of divorcing persons) and the District of Columbia, representing 49% of all divorces. The DRAs were constructed to be nationally representative of the population (Clarke, 1995).

To estimate the numbers of persons aged 50 and older, aged 50–64, and aged 65 and older divorcing in 1970, 1980, and 1990, we adjusted the DRA numbers to ensure they represented all divorces, meaning we divided the age-specific numbers of persons by the share of the divorces represented by the DRA (i.e., 0.61, 0.49, and 0.49 in 1970, 1980, and 1990, respectively). This was the same approach used by Brown and Lin (2012), who after exploring other options (e.g., using census data from the corresponding year and applying the divorce rate to the married population to estimate the number of divorces), concluded this one was preferable because it offers the most conservative estimates. The U.S. Vital Statistics reports are the best available data to estimate age-specific divorce rates from 1970 to 1990. In fact, Kennedy and Ruggles (2014, p. 593) asserted that the 1970, 1980, and 1990 age-specific divorces rates for the DRA “were probably the highest-quality divorce statistics ever gathered by NCHS.” Post-1990, the ACS data are the premier source for divorce statistics. Pointing to “significant underreporting of divorces in vital records after 1990,” Kennedy and Ruggles (2014, p. 592) concluded that “the ACS estimates [we]re more credible than the vital statistics.” The U.S. Census Bureau performed a state-level validation analysis that revealed the U.S. Vital Statistics (including the DRA sample) and the ACS were comparable (Elliott, Simmons, & Lewis, 2010). Furthermore, Brown and Lin (2012) confirmed the robustness of their 2010 gray divorce rate estimates by restricting analyses of the 2010 ACS to just those states that were in the 1990 DRA sample and obtained the same results as they did using the full 2010 ACS sample from all states.

2010 and 2019 ACS

A large, nationally representative survey administered annually by the U.S. Census Bureau, the ACS included questions designed to obtain information previously collected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control Vital Statistics program, which was discontinued in 1996 (Elliott et al., 2010). Beginning in 2008, the ACS included three marital history questions capturing whether respondents experienced a marital event (i.e., marriage, divorce, or widowhood) in the past year, allowing the calculation of the divorce rate by age. Our analytic sample was composed of middle-aged and older adults. In 2010, the ACS sampled 3,061,692 persons, of which 757,835 were aged 50 and older and at risk of gray divorce (as defined in the next paragraph), including 462,812 middle-aged (50–64) and 295,023 older adults (aged 65 and older). In 2019, the ACS included 3,239,553 persons, of which 892,714 were aged 50 and older and at risk of gray divorce (as defined in the next paragraph), including 477,134 middle-aged and 415,580 older adults.

The Divorce Rate

To calculate the divorce rate in the 2010 and 2019 ACS, we divided the number of people who reported a divorce in the past 12 months by the number of people at risk of divorce during the past 12 months. Those at risk of divorce during the past 12 months (i.e., the denominator) included individuals who got divorced or became widowed in the past 12 months as well as those who reported being married or separated at the interview. The leading data source for estimating U.S. divorce rates, the ACS has been used widely by researchers for this purpose (Cohen, 2019; Ratcliffe et al., 2008).

Sociodemographic Variables

Age group differentiated between middle-aged (aged 50–64) and older (aged 65 and older, reference category) adults.

The marital biography encompassed marriage order and marital duration. Marriage order distinguished between individuals in a first marriage (reference category) versus a higher order marriage (i.e., a remarriage). For those who either did not experience a divorce in the past year or who divorced but were not currently married at interview, marriage order was assigned using the number of times married reported at the interview. For those who both divorced and married in the past year and were currently married at interview, marriage order was calculated as the number of times married reported at interview minus one (because the current marriage occurred after divorce). Two respondents in 2010 and seven respondents in 2019 reported both divorcing and being widowed in the past year, making it impossible to determine their marriage order and thus they were excluded from the analyses. Marital duration of the current or dissolved in the past 12 months marriage was coded: 0–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, and 40 or more years (reference category). For the respondents who reported getting divorced and married in the past year and being currently married at interview, we could not obtain the length of their marriage that ended in divorce and thus we assigned the mean value for marital duration for respondents who experienced a gray divorce in the past year. This mean substitution was performed for 272 and 235 respondents in 2010 and 2019, respectively.

Demographic characteristics included gender and race-ethnicity. Gender was coded 1 for women and 0 for men. Race-ethnicity was gauged using a series of binary variables: Non-Hispanic White (reference category), Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, and Non-Hispanic Other (this category included multiracial persons along with those who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native or some other race).

Economic resources included education, employment, and income. Education distinguished among those with less than a high school diploma, a high school diploma (reference category), some college, and a college degree or beyond. Employment captured whether individuals were employed full-time (at least 35 hr/week), part-time (1–34 hr/week), unemployed (i.e., searching for work), or not in the labor force (reference category) for the past 12 months. Personal income gauged the individual’s income from all sources over the past 12 months, coded into the following levels: less than $10,000, $10,000–$24,999, $25,000–$39,999, $40,000–$54,999, $55,000–$69,999, and $70,000 or more (reference category).

Analytic Strategy

Our analyses proceeded in three steps. First, to establish the historical trend in gray divorce, we charted the timing and tempo of change in the gray divorce rate over the past nearly 50 years (1970–2019) for adults aged 50 and older as well as separately for middle-aged and older adults. We also estimated the shares of middle-aged versus older adults who experienced gray divorce at each time point (i.e., 1970, 1980, 1990, 2010, and 2019) to appraise potential compositional shifts in the age distribution of those divorcing.

Second, we estimated 2019 divorce rates for sociodemographic subgroups to illustrate how the risk of gray divorce differed by the marital biography, demographic characteristics, and economic resources for adults aged 50 and older as well as separately for middle-aged and older adults. Supplemental analyses shown in Supplementary Table 1 depicted the bivariate comparisons across these same factors for those who experienced gray divorce versus remained married.

Third, we performed logistic regression analyses predicting the likelihood of gray divorce, net of survey year (2010 vs 2019), age group, the marital biography, demographic characteristics, and economic resources. This initial model permitted us to test whether the risk of gray divorce significantly changed between 2010 and 2019. A second model introduced an interaction term for survey year and age group to test whether the risk of gray divorce declined among middle-aged adults and rose among older adults. The logistic regression models only offer correlational evidence as covariates were measured at the time of interview whereas divorce occurred during the past year. The measures of employment and personal income gauged levels over the past 12 months, but causal order between these two factors and divorce remains fuzzy, making it important to avoid drawing any causal conclusions from the analyses. All analyses were performed using replicate weighting techniques as recommended by Census to address the complex sampling design of the ACS and generate robust standard errors (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

Results

The Historical Trend in Gray Divorce

Figure 1 depicts the arc of gray divorce across a nearly half century time span. From 1970 to 1990, the gray divorce rate for adults aged 50 and older was low and grew very modestly, increasing from 3.69 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons in 1970 to 4.08 per 1,000 in 1980 to 4.87 per 1,000 in 1990. As documented elsewhere (Brown & Lin, 2012), between 1990 and 2010, the gray divorce rate doubled to 10.05 per 1,000. Since then, the rate declined slightly to 9.64 per 1,000 in 2019.

Figure 1.

The gray divorce rate by age group, 1970–2019.

The patterns for middle-aged and older adults were distinctive. For middle-aged adults, the gray divorce rate rose moderately from 1970 to 1990, climbing from 4.85 per 1,000 in 1970 to 5.57 per 1,000 in 1980, and then to 6.90 per 1,000 in 1990. It nearly doubled by 2010 when it stood at 13.05 per 1,000. Since then, the rate declined somewhat to 12.72 per 1,000, signaling that gray divorce may be waning among the middle-aged.

In contrast, gray divorce among older adults was quite low during the 1970–1990 period, with very little increase in the rate. In 1970, the older adult divorce rate was a mere 1.40 per 1,000, and in 1980 it was largely unchanged at 1.47 per 1,000. By 1990, the rate had crept up to just 1.79 per 1,000. Between 1990 and 2010, the gray divorce rate among older adults more than doubled to 4.84 per 1,000 and, unlike the downturn we documented for middle-aged adults since 2010, for older adults the gray divorce rate continued its ascent, climbing to 5.60 per 1,000 in 2019. Supplemental analyses (not shown) indicated the gray divorce rate rose between 2010 and 2019 for both those aged 65–74 and those aged 75 and older. The modest decrease in divorce among the middle-aged combined with the increase among older adults foretells convergence in the rates of divorce for middle-aged and older adults, which is consonant with the broader trend towards less age variation in the divorce rate (Cohen, 2019).

Indeed, the age composition of those experiencing divorce is shifting to later ages as divorce rates have continued to fall among younger adults while rates have risen for those in the second half of life. During the 1970–1990 period, relatively few divorces occurred among adults 50 and older. For example, in 1970 and 1980, just 7.8% and 7.1%, respectively, of all persons divorcing experienced gray divorces. In 1990, the corresponding figure was 8.7%. By 2010, more than one in four (27%) people getting divorced were aged 50 or older. As of 2019, an astounding 36% of people—more than one in three—getting divorced were aged 50 and older. In fact, nearly one in ten (9%) persons divorcing in 2019 was at least aged 65. These figures illustrate the graying of divorce over the past five decades, reflecting both the rise in the gray divorce rate and the aging of the married population over this time period.

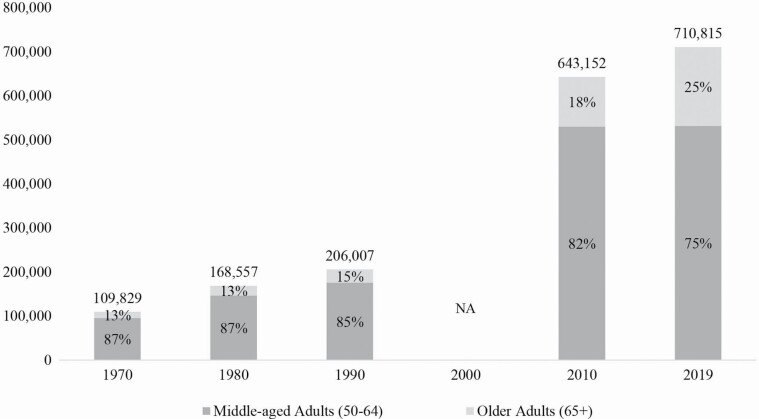

Figure 2 shows estimates of the numbers of adults experiencing gray divorce since 1970, differentiating between the shares of middle-aged versus older adults. In 1970, roughly 109,829 adults got a gray divorce and nearly all (87%) occurred to those in middle age rather than older adulthood (13%). By 1990, the number had nearly doubled to 206,007 but the proportions by age group remained fairly stable (85% were to middle-aged adults and 15% to older adults). Between 1990 and 2010, the number of persons aged 50 and older experiencing divorce grew dramatically for both middle-aged and older adults. In 2010, an estimated 643,152 people aged 50 and older experienced divorce, with 18% aged 65 and older. Since 2010, the number of divorcing in middle age remained flat with essentially all growth occurring among older adults. In 2019, about 710,815 adults aged 50 and older divorced, of which 25% were older adults.

Figure 2.

Number of adults experiencing gray divorce and percentages middle-aged versus older adults, 1970–2019.

The dramatic increase in the sheer number of adults experiencing a gray divorce over the 1970–2019 period is important because it conveys the magnitude of the impact of this phenomenon. To illustrate the extent to which this sizeable number of adults experiencing gray divorce in 2019 reflects the rise in the gray divorce rate (as opposed to the aging of the married population), we applied the 1970 gray divorce rate to the 2019 married population aged 50 and older. If the 1970 gray divorce rate prevailed in 2019, only 272,052 adults aged 50 and older would have experienced a gray divorce. Just 16% of them would have been aged 65 or older. In short, not only is gray divorce much more widespread than in the past, but it has been gaining ground among older adults as its prevalence among the middle-aged has stalled.

Sociodemographic Variation in the 2019 Gray Divorce Rate

Table 1 shows the 2019 divorce rates across sociodemographic subgroups for adults aged 50 and older as well as separately for middle-aged and older adults. For all subgroups, the divorce rate was significantly higher for middle-aged than older adults, as indicated in the far right column of the table. Individuals in a higher order marriage faced a gray divorce rate that was roughly twice that of those in a first marriage: 14.21 versus 7.59 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons. This difference was evident among the middle-aged, too (18.35 vs 10.32 per 1,000) and was even larger among older adults (9.18 vs 3.90 per 1,000). The gray divorce rate declined monotonically by marital duration. The rate was 18.13 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons for those married less than 10 years versus 3.80 per 1,000 for those married at least 40 years. This pattern held for both middle-aged and older adults.

Table 1.

The 2019 Gray Divorce Rates Across Marital Biography, Demographic Characteristics, and Economic Resources, by Age Group

| Fifty and older | Fifty to sixty-four | Sixty-five and older | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (2) versus (3) | |

| Total | 9.64 | 12.72 | 5.60 | *** |

| Marital biography a | ||||

| Marriage order | ||||

| First marriage | 7.59 | 10.32 | 3.90 | *** |

| Higher order marriage | 14.21 | 18.35 | 9.18 | *** |

| Marital duration (years) | ||||

| 0–9 | 18.13 | 18.73 | 16.05 | |

| 10–19 | 15.03 | 16.65 | 10.07 | *** |

| 20–29 | 13.92 | 15.01 | 9.82 | *** |

| 30–39 | 8.17 | 8.60 | 6.93 | ** |

| >40 | 3.80 | 6.00 | 3.37 | *** |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 9.96 | 12.87 | 5.81 | *** |

| Men | 9.33 | 12.57 | 5.43 | *** |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| White | 8.51 | 11.87 | 4.61 | *** |

| Black | 17.40 | 20.42 | 12.28 | *** |

| Hispanic | 11.95 | 13.38 | 8.90 | *** |

| Asian | 8.21 | 9.56 | 6.06 | *** |

| Others | 12.69 | 14.84 | 8.66 | *** |

| Economic resources | ||||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 11.51 | 14.29 | 8.31 | *** |

| High school graduate | 10.10 | 13.49 | 5.96 | *** |

| Some college | 10.58 | 14.15 | 5.55 | *** |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 7.84 | 10.41 | 4.35 | *** |

| Employment | ||||

| Not in labor force | 7.08 | 12.09 | 5.02 | *** |

| Unemployed | 24.37 | 25.86 | 17.02 | |

| Worked part-time | 9.79 | 11.88 | 6.68 | *** |

| Worked full-time | 12.00 | 12.69 | 7.65 | *** |

| Personal income | ||||

| <10K | 8.77 | 11.26 | 5.46 | *** |

| 10–25K | 9.97 | 15.38 | 6.12 | *** |

| 25–40K | 11.24 | 15.53 | 6.43 | *** |

| 40–55K | 10.26 | 13.51 | 5.34 | *** |

| 55–70K | 9.27 | 11.82 | 5.01 | *** |

| >70K | 8.79 | 10.75 | 4.53 | *** |

| Unweighted N | 892,714 | 477,134 | 415,580 |

Notes: The divorce rate is the number of divorced persons per 1,000 married persons. Source: American Community Survey, 2019.

aSeven gray-divorced persons (unweighted) for whom marriage order could not be determined were excluded.

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

The gray divorce rates for women and men were nearly the same at 9.96 and 9.33 divorcing persons, respectively, per 1,000 married persons. This pattern was obtained for both middle-aged and older adults. Across racial-ethnic groups, the gray divorce rate ranged from a low of 8.21 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons for those who identified as Asian to a high of 17.40 per 1,000 for adults who identified as Black. Hispanic identifying adults were in between at 11.95 per 1,000 and individuals who reported other racial identities had a gray divorce rate of 12.69 per 1,000. The gray divorce rate for adults who identified as White was 8.51 per 1,000. For middle-aged adults, the pattern was similar whereas among older adults, the divorce rate for Asians was somewhat higher than for Whites.

The gray divorce rate tended to decline across education levels, although the increments were modest among those with less than a college degree. The gray divorce rate for adults who did not complete high school was 11.51 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons. By comparison, among those who completed some college, the rate was 10.58 per 1,000. The college educated experienced a lower gray divorce rate of 7.84 per 1,000. This pattern held for middle-aged adults but not for older adults, among whom those with a high school diploma or some college appeared more similar to the college educated than those with no high school diploma. The gray divorce rate differed markedly by employment status with the unemployed experiencing a rate more than twice that of others. Among the unemployed, the gray divorce rate was 24.37 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons. For those not in the labor force, the rate was just 7.08 per 1,000. The rate was a bit higher for the employed: 9.79 per 1,000 for those working part-time and 12.00 per 1,000 for those employed full-time. These differences obtained among middle-aged and older adults alike. In contrast, the variation across personal income groups was modest. Gray divorce rates were lowest among the lowest and highest-earning adults. For those earning less than $10,000 or more than $70,000 in the past year, the rate was essentially identical at 8.8 divorcing persons per 1,000 married persons. Middle-income adults earning $25,000–$39,999 and $40,000–$54,999 experienced the highest gray divorce rates at 11.24 and 10.26, respectively, per 1,000. The variation in the gray divorce rate across personal income groups was evident primarily for middle-aged adults; only very small differences emerged among older adults.

Changing Risks of Gray Divorce Between 2010 and 2019

Table 2 shows the logistic regression models predicting the likelihood of divorce. Model 1 included the survey year and all covariates to gauge whether the odds of divorce changed over the past nine years net of sociodemographic factors. The odds of divorce remained unchanged between 2010 and 2019, indicating that gray divorce stalled over this time period. As expected, the odds of divorce were 1.54 times higher for middle-aged than older adults. Remarried adults faced odds of divorce that were 1.41 times that of their first married counterparts. Marital duration was negatively associated with the odds of divorce. Women were more likely than men to experience divorce. Individuals who identified as Black, Hispanic, or other race faced higher odds of divorce than those who identified as White. The risk of gray divorce was comparable for individuals who identified as Asian or White. The least educated were at the greatest risk of divorce, whereas the most educated enjoyed the lowest risk of divorce compared with individuals who had a high school diploma. Relative to those not in the labor force, all others experienced higher odds of divorce. Middle-income adults had larger odds of divorce than high-income adults, but the latter group did not appreciably differ from the lowest income group. These demographic covariates operated similarly in 2010 and 2019 (results not shown). In supplemental analyses (Supplementary Table 2), we disaggregated older adults to distinguish between those aged 65–74 in the Baby Boomer generation versus those aged 75 and older in previous generations and found that the 65–74-year-old age group was at higher risk of gray divorce than the >75 age group.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios From Logistic Regressions of the Likelihood of Gray Divorce in the Last 12 Months

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey year | ||||

| 2010 (reference category) | ||||

| 2019 | 1.024 | 1.136 | ** | |

| Age group | ||||

| 50–64 | 1.542 | *** | 1.666 | *** |

| >65 (reference category) | ||||

| Survey year (2019) × Age group (50–64) | 0.876 | * | ||

| Marital biography | ||||

| Marriage order | ||||

| First marriage (reference category) | ||||

| Higher order marriage | 1.406 | *** | 1.403 | *** |

| Marital duration | ||||

| 0–9 years | 3.327 | *** | 3.326 | *** |

| 10–19 years | 2.717 | *** | 2.713 | *** |

| 20–29 years | 2.623 | *** | 2.620 | *** |

| 30–39 years | 1.624 | *** | 1.618 | *** |

| >40 years (reference category) | ||||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 1.110 | *** | 1.109 | *** |

| Men (reference category) | ||||

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| White (reference category) | ||||

| Black | 1.768 | *** | 1.767 | *** |

| Hispanic | 1.104 | * | 1.104 | * |

| Asian | 0.910 | 0.910 | ||

| Others | 1.360 | *** | 1.360 | *** |

| Economic resources | ||||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 1.228 | *** | 1.231 | *** |

| High school graduate (reference category) | ||||

| Some college | 1.027 | 1.026 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 0.852 | *** | 0.851 | *** |

| Employment | ||||

| Not in labor force (reference category) | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.924 | *** | 1.916 | *** |

| Worked part-time | 1.084 | * | 1.085 | * |

| Worked full-time | 1.158 | *** | 1.159 | *** |

| Personal income | ||||

| <10K | 1.039 | 1.039 | ||

| 10–25K | 1.229 | *** | 1.228 | *** |

| 25–40K | 1.194 | *** | 1.192 | *** |

| 40–55K | 1.084 | * | 1.082 | * |

| 55–70K | 1.032 | 1.031 | ||

| >70K (reference category) | ||||

| Constant | 0.002 | *** | 0.002 | *** |

| Unweighted N | 1,650,540 | 1,650,540 | ||

| F (23, 57) = 146.60 | F (24, 56) = 139.48 |

Note: Source: American Community Survey, 2010 and 2019.

*p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

Model 2 added an interaction term for survey year and age group to test whether the likelihood of divorce for middle-aged versus older adults differed between 2010 and 2019. As anticipated, the interaction term was significant and negative. To decipher this interaction effect, we estimated separate models by age group (results not shown) and determined that the risk of divorce for today’s (2019) middle-aged adults did not appreciably differ from the risk they faced in 2010. In contrast, today’s older adults experienced significantly higher odds of divorce than they did nearly a decade ago. As divorce has stagnated among the middle-aged, it has been accelerating among older adults.

Discussion

Over the past half century, the United States has witnessed the graying of divorce. The gray divorce rate was low and rose only modestly between 1970 and 1990 before doubling by 2010. Since 2010, the gray divorce rate has attenuated slightly (the decline does not achieve statistical significance). At the same time, a growing share of all divorces in the United States involves a spouse aged 50 and older, reflecting both the rise in the gray divorce rate and the aging of the married population. Whereas fewer than one in 10 people divorcing in 1970, 1980, and 1990 were aged 50 or older, by 2010 the share was one in four. As of 2019, one in three people getting divorced in the United States was aged 50 or older, a vivid illustration of the graying of divorce.

In addition to charting the timing and tempo of the rise in gray divorce since 1970, we also uncovered distinctive trends for middle-aged versus older adults that portend a shifting trajectory of gray divorce in the coming years. Although the divorce rate for older adults trails that of middle-aged adults, the acceleration in divorce has occurred more quickly among older adults, particularly since 2010, and thus the gap between these two groups is narrowing. A half century ago, middle-aged adults were 3.5 times (4.85/1.40) as likely as older adults to experience divorce. Now, the differential has shrunk as the divorce rate for the middle-aged is only about 2.3 times (12.72/5.60) higher than the rate for older adults. The composition of those experiencing gray divorce has shifted accordingly with the share who are older (vs middle-aged) adults having nearly doubled from 13% to 25% between 1970 and 2019. Divorce is no longer rising among the middle-aged, who now join their younger counterparts in experiencing a downward trend in their risk of divorce. The only age group for whom divorce is increasing is older adults aged 65 and beyond. They now face record high divorce rates.

Over the past decade, the likelihood of divorce has risen among older adults and stalled among middle-aged adults. These disparate trends likely are due to the aging of the Baby Boomer generation, who in 2010 composed the middle-aged group but now in 2019 make up much of the older adult group. Succeeding generations, namely Generation X, have begun to age into middle age. It appears that gray divorce increasingly will be the province of older rather than middle-aged adults. Our study provides suggestive evidence that gray divorce may be distinctly prominent among Baby Boomers, which is consonant with the uniquely high divorce rates they have experienced across the adult life course. The divorce rates of Boomers during young adulthood outpaced those of succeeding generations at the same life course stage. Now, our research indicates that the elevated divorce rates experienced by Baby Boomers during middle age in 2010 also were distinctive as the succeeding generation in 2019 did not experience a corresponding rise in midlife divorce rates. Rather, the apparent deceleration in divorce among the middle-aged may be a harbinger of decline in gray divorce for this age group in the years to come as succeeding generations came of age during an era marked by a rising age at first marriage and falling young adult divorce rates. We stress that we are unable to draw firm conclusions about whether the gray divorce phenomenon in the United States will ebb as Baby Boomers move into old age and eventually die, but our work offers important clues that point in this direction. And, it affirms recent speculation by other scholars about the future of gray divorce (Raley & Sweeney, 2020; Smock & Schwartz, 2020).

By tracing the gray divorce trend over the past half century and uncovering the unique contours of this trend for middle-aged versus older adults, our study makes important contributions to the literature but also has some limitations. First, even though we were able to pool 2010 and 2019 ACS data to examine the changing associations between sociodemographic correlates and gray divorce, the results of our study are correlational only and should not be construed as causal. Second, we relied on microdata only and thus could not empirically appraise the role of broad societal shifts (e.g., changing attitudes toward marriage and divorce, the rise in women’s labor force participation, and lengthening life expectancy) that we believe underlie the rise in gray divorce. Of course, it is exceedingly difficult if not impossible to assess the linkages between such macro-level factors and the rise of gray divorce with existing data. Finally, we offered suggestive evidence that gray divorce may be a distinct life course event for Baby Boomers whose divorce proneness has been evident since they were young adults. Our evidence aligns with recent scholarly prognostications about gray divorce patterns (Raley & Sweeney, 2020; Smock & Schwartz, 2020). However, we were not able to draw definitive conclusions and can merely offer our supposition that the divorce rate for the middle aged (and eventually older adults) will continue to decline over the next decade or two as succeeding generations replace the Baby Boomer generation in these age groups.

Divorce is now a common event during the second half of life. Most gray divorces continue to occur among the middle-aged, but older adults are rapidly gaining ground. One in four persons experiencing a gray divorce in 2019 was aged 65 or older. Divorce is stalling among the middle-aged yet continues to climb among older adults. Ultimately, older adults will increasingly experience marital dissolution through gray divorce rather than widowhood, making it essential that researchers investigate the unique ramifications of gray divorce for older adult health and well-being.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Susan L Brown, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, USA.

I-Fen Lin, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, USA.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R15AG047588). Additional support was provided by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD050959).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bair, D. (2007). Calling it quits: Late-life divorce and starting over. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Berardo, D. H. (1982). Divorce and remarriage at middle age and beyond. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 464, 132–139. doi: 10.1177/0002716282464001012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L., & Lin, I. F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L., Lin, I. -F., Hammersmith, A. M., & Wright, M. R. (2018). Later life marital dissolution and repartnership status: A national portrait. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, 1032–1042. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L., & Wright, M. R. (2019). Divorce attitudes among older adults: Two decades of change. Journal of Family Issues, 40, 1018–1037. doi: 10.1177/0192513X19832936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D., & Utz, R. L. (2020). Families in later life: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 346–363. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin, A. J. (1992). Marriage, divorce, remarriage. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin, A. J. (2009). The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. C. (1995). Advance report of final divorce statistics, 1989 and 1990. (Monthly Vital Statistics Report, Vol. 43, No. 8). National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, P. N. (2019). The coming divorce decline. Socius, 5, 1–6. doi: 10.1177/2378023119873497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey, A., & Szinovacz, M. E. (2004). Dimensions of marital quality and retirement. Journal of Family Issues, 25, 431–464. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03257698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D. B., Simmons, T., & Lewis, J. M. (2010). Evaluation of the marital events items on the ACS. http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/marriage/data/acs/index.html

- Hammond, R. J., & Muller, G. O. (1992). The late-life divorced: Another look. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 17, 135–150. doi: 10.1300/j087v17n03_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiedemann, B., Suhomlinova, O., & O’Rand, A. M. (1998). Economic independence, economic status, and empty nest in midlife marital disruption. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 219–231. doi: 10.2307/353453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karraker, A., & Latham, K. (2015). In sickness and in health? Physical illness as a risk factor for marital dissolution in later life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56, 420–4 35. doi: 10.1177/0022146515596354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, S., & Ruggles, S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51, 587–5 98. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0270-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I. F., Brown, S. L., Wright, M. R., & Hammersmith, A. M. (2018). Antecedents of gray divorce: A life course perspective. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, 1022–1031. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (1974). Vital statistics of the United States, 1970 (DHEW Publication No. 75-1103). U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/mgdv70_3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (1985). Vital statistics of the United States, 1980 (PHS Publication No. 85-1103). U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/mgdv80_3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2020). Mortality in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db395-tables-508.pdf#page=1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley, R. K., & Sweeney, M. M. (2020). Divorce, repartnering, and stepfamilies: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 81–99. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, C., Acs, G., Dore, T., & Moskowitz, D. (2008). Assessment of survey data for the analysis of marriage and divorce at the national, state, and local levels. The Urban Institute. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2206390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smock, P. J., & Schwartz, C. R. (2020). The demography of families: A review of patterns and change. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 9–34. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenberg, P., Cooney, T., & Boyd, R. (1990). Divorce for women after midlife. Journal of Gerontology, 45, S3–S 11. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.1.s3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenberg, P., & Myers, M. A. P. (1981). Divorce and the elderly. The Gerontologist, 21, 276–282. doi: 10.1093/geront/21.3.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. (2014). American CommunitySurvey design and methodology.https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/methodology/design_and_methodology/acs_design_methodology_report_2014.pdf

- Wu, Z., & Schimmele, C. M. (2007). Uncoupling in late life. Generations, 31, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.