Abstract

Background

Despite significant differences in surgical outcomes between pediatric and adult patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) undergoing colectomy, counseling on pediatric outcomes has largely been guided by data from adults. We compared differences in pouch survival between pediatric and adult patients who underwent total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA).

Methods

This was a retrospective single-center study of patients with UC treated with IPAA who subsequently underwent pouchoscopy between 1980 and 2019. Data were collected via electronic medical records. We stratified the study population based on age at IPAA. Differences between groups were assessed using t tests and chi-square tests. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare survival probabilities. Differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test.

Results

We identified 53 patients with UC who underwent IPAA before 19 years of age and 329 patients with UC who underwent IPAA at or after 19 years of age. Subjects who underwent IPAA as children were more likely to require anti-tumor nerosis factor (TNF) postcolectomy compared with adults (41.5% vs 25.8%; P < .05). Kaplan-Meier estimates revealed that pediatric patients who underwent IPAA in the last 10 years had a 5-year pouch survival probability that was 28% lower than that of those who underwent surgery in the 1990s or 2000s (72% vs 100%; P < .001). Further, children who underwent IPAA and received anti-TNF therapies precolectomy had the most rapid progression to pouch failure when compared with anti-TNF–naive children and with adults who were either exposed or naive precolectomy (P < .05).

Conclusions

There are lower rates of pouch survival for children with UC who underwent IPAA following the uptake of anti-TNF therapy compared with both historical pediatric control subjects and contemporary adults.

Keywords: IPAA, pouch, pouchitis, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that manifests as continuous mucosal inflammation beginning in the rectum and extending proximally in the colon. Therapies used for medical management include aminosalicylates, immunomodulators, biologic drugs, and more recently, small molecule JAK kinase inhibitors. Despite long-standing and emerging pharmacologic options, disease progression leads to eventual total proctocolectomy in 10% to 15% of those diagnosed with UC.1

Total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) with J-pouch configuration is the most common surgical approach for UC refractory (or resistant) to medical therapy as well as for those seeking an alternative to immunosuppressive medications.2-4 While outcomes are better defined in adult cohorts,5-8 less is known about the outcomes of pediatric subjects undergoing IPAA. Recent systematic reviews have helped refine our understanding of IPAA complications and prognosis in children.9,10 However, heterogeneity in pediatric age cutoffs, preoperative diagnoses with some studies including subjects with Crohn’s disease (CD), IBD-unclassified, and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) in outcomes and surgical approach may limit ability to provide patient-families with a clear prognosis before surgery.4

In this study, we compared IPAA outcomes between pediatric and adult patients with UC (excluding CD and IBD-unclassified) using data collected at our IBD Center. We also performed a temporal analysis, revealing lower rates of pouch survival in children after uptake of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy compared with both contemporary adults and historical pediatric control subjects.

Methods

Data Source

In this retrospective cohort analysis at a single-center tertiary care hospital, we used our medical center’s electronic medical record data warehouse to identify IBD patients who underwent IPAA between January 1980 and May 2017. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago (#16-0061, #15573A). Through chart review, we also collected general demographic data; clinical information pertaining to medication exposure, indication for surgery, and surgical technique; and the results of postoperative pouchoscopies until December 31, 2019, for these patients. All available pouchoscopies after ileostomy takedown were reviewed and findings were characterized based on the endoscopy descriptions and images further detailed in our group’s initial report.11 Pouchoscopy indications ranged from asymptomatic monitoring to symptomatic assessment and dysplasia surveillance. All data were stored using REDCap (Research Electronic Data capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Chicago (National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 TR000430).12

Outcomes Definitions

The primary outcome in this study was pouch failure and was defined as pouch excision at any time point after ileostomy takedown (or any time postcolectomy in cases of a single-stage procedure). Secondary outcomes included postoperative pouchitis and de novo CD of the pouch. Pouchitis was defined as 1 or more endoscopic findings of inflammation in the tip, proximal, or distal pouch. Subjects with symptoms of pouchitis but no active inflammation were not included by this categorization. De novo CD of the pouch, though informed by clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features, was defined solely according to the treating physician’s expert opinion.

Statistical Analysis

For this study, only patients with a preoperative diagnosis of UC were included. Exclusion criteria included a colectomy specimen not consistent with UC, subject records lacking data on eventual pouch failure, or if no pouchoscopy was documented before pouch excision. The study population was then stratified into a pediatric and adult surgery cohort to compare differences in demographic and clinical background between groups. The pediatric cohort included all patients who underwent surgery at 18 years of age or younger. Missing values for categorical variables were assumed to be missing and were coded as unknown.

To compare postoperative outcomes between pediatric and adult surgery patients, we looked at rates of exposure to anti-TNF therapy in the years following surgery and rates of eventual pouch failure. Exposure to anti-TNF therapies after surgery was defined as postoperative use of adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, or certolizumab pegol. We conducted a similar analysis to compare differences in rates of postoperative anti-TNF exposure and pouch failure between patients who underwent IPAA as children and children diagnosed with UC who underwent surgery as adults. In all cases, differences between groups were compared using a chi-square test for categorical variables and a Student’s t test for continuous variables.

A Kaplan-Meier analysis was conducted to plot unadjusted pouch survival based on decade of surgery and preoperative exposure to anti-TNF therapies. Survival time was defined as the time between the date of surgery (this would be the last stage if the surgery was a multistage procedure) and the date of pouch excision, censored for the last date of follow-up. Differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version 1.2.5001 (RStudio, Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Study Population

A total of 1359 pouchoscopies corresponding to 426 unique patients were reviewed. After stratifying our study population based on timing of surgery, we identified 60 subjects who underwent IPAA as children (at 18 years of age or younger) and 364 subjects who underwent surgery as adults (at ≥19 years of age). After dropping observations that lacked a preoperative diagnosis of UC, we identified 53 patients who underwent IPAA before 19 years of age and 329 who underwent the procedure after 19 years of age (Table 1). The mean age at time of UC diagnosis was 13 years in the pediatric cohort and 29 years in the adult cohort (13.2 ± 4.2 years of age pediatric vs 28.5 ± 10.7 years of age adult; P < .001). The mean age at the time of surgery was 16 years in the pediatric cohort and 36 years in the adult cohort (16.1 ± 2.5 years of age pediatric vs 36.2 ± 11.5 years of age adult; P < .001). The number of years between the year of diagnosis and year of colectomy was significantly lower in the pediatric cohort (2.9 ± 2.8 years pediatric vs 7.0 ± 8.6 years adult; P = .001). For those who experienced pouch failure, the number of years between year of colectomy and year of pouch failure was not significantly different between groups (9.5 ± 3.4 years pediatric vs 11.5 ± 3.5 years adult; P = .41). The percentage of female patients was 13% higher in the pediatric cohort (54.7% pediatric surgery vs 41.6% adult surgery; P = .10), and the cohorts were evenly distributed by race. Family history of IBD was described in 28% of subjects. There was no observed statistical difference in surgical approach between pediatric and adult groups, with 92% of all procedures being completed in either 2 or 3 stages and 72% of anastomoses being stapled (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population stratified by age at IPAA (n = 382)

| IPAA ≥19 Years of Age (n = 329) | IPAA <19 Years of Age (n = 53) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | 28.5 ± 10.7 | 13.2 ± 4.2 | <.001 |

| Age at colectomy, y | 36.2 ± 11.5 | 16.1 ± 2.5 | <.001 |

| Time to colectomy, y | 7.0 ± 8.6 | 2.9 ± 2.8 | .001 |

| Female | 137 (41.6) | 29 (54.7) | .13 |

| Pediatric diagnosis (<19 years of age) | 58 (18.0) | 53 (100) | <.001 |

| Race | .13 | ||

| White | 294 (89.4) | 48 (92.4) | |

| Asian | 16 (4.9) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Black or African American | 13 (4.0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| More than 1 race | 1 (0.3) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Other | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Family history | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 60 (18.2) | 11 (19.2) | .81 |

| CD | 31 (9.4) | 9 (15.4) | .15 |

| Indeterminate colitis | 6 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | .70 |

| Clostridioides difficile infection before surgery | 54 (16.4) | 11 (20.8) | .56 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis before surgery | 14 (4.3) | 2 (3.8) | 1.00 |

| Diagnosis change to CD after colectomy | 97 (29.8) | 20 (38.0) | .32 |

| Pouchitis | 270 (82.1) | 41 (77.4) | .53 |

| Pouch failure | 32 (9.7) | 10 (18.9) | .08 |

| Time from colectomy to pouch failure, y | 9.5 ± 6.8 | 11.5 ± 6.9 | .41 |

| Time of follow-up postcolectomy, y | 10.6 ± 7.1 | 13.7 ± 7.7 | .003 |

| Surgical indication | |||

| Refractory disease | 259 (78.7) | 42 (80.8) | 1.00 |

| Dysplasia | 34 (10.3) | 1 (1.9) | .09 |

| Colorectal cancer | 13 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | .29 |

| Fulminant colitis | 35 (10.6) | 11 (20.8) | .06 |

| Toxic megacolon | 8 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | .53 |

| Type of surgery a | .44 | ||

| 1 stage | 24 (7.9) | 3 (7.7) | |

| 2 stage | 113 (37.4) | 11 (27.5) | |

| 3 stage | 165 (54.6) | 26 (65.0) | |

| Surgical technique a | 1.00 | ||

| Hand-sewn anastomosis | 75 (27.1) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Stapled anastomosis | 202 (72.9) | 26 (72.2) | |

| Decade of surgery a | .01 | ||

| 1990s | 62 (19.3) | 20 (38.5) | |

| 2000s | 149 (46.4) | 22 (42.3) | |

| 2010s | 110 (34.3) | 10 (19.2) | |

| Medications before surgery | |||

| Anti-TNF | 147 (44.7) | 17 (32.1) | .12 |

| Immunomodulators | 205 (62.3) | 25 (47.2) | .05 |

| 5-ASA | 256 (77.8) | 35 (66.0) | .09 |

| Steroids | 280 (85.1) | 44 (83.0) | .85 |

| Antibiotics | 64 (19.5) | 10 (19.2) | .97 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%). Time to colectomy is defined as the number of years between the year of diagnosis and year of IPAA. Immunomodulator use before surgery was defined as the use of azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus. Antibiotic use before surgery included use of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, or rifaximin.

Abbreviations: 5-ASA, 5-acetylsalicylic acid; CD, Crohn’s disease; IPAA, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Where reported surgical data were available.

Complication Rates for Pediatric IPAA

Outcomes for children with UC who underwent IPAA were followed for an average of 13.7 ± 7 years (minimum of 2.7 years). An overall pouchitis rate of 77.4% (n = 41) was found, with 18.9% (n = 10) who experienced pouch loss. A change in diagnosis from UC before colectomy to de novo CD following IPAA was seen in 38.0% (n = 20) of pediatrics subjects and in 7 of 10 children who had pouch failure (Table 1).

Higher Rates of Postoperative Anti-TNF for IPAA in Childhood vs Adulthood

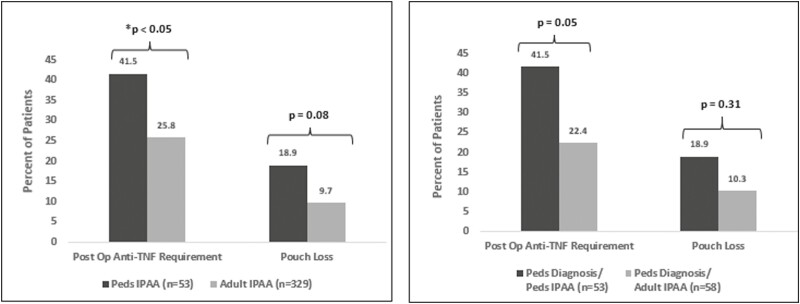

Comparisons of postsurgical outcomes between pediatric and adult surgical patients revealed that 15.7% more pediatric surgery patients were treated with anti-TNF medications in the years following surgery than adult surgery patients (41.5% pediatric surgery vs 25.8% adult surgery; P < .05). Pouch failure trended higher in the group that underwent surgery in childhood; however, this did not reach statistical significance (18.9% pediatric surgery vs 9.7% adult surgery; P = .08) (Figure 1). Similar results are seen when comparing pediatric IPAA (n = 53) with subjects diagnosed as children but who underwent IPAA in adulthood (n = 58). As expected, the observed time from diagnosis to colectomy was significantly shorter in the pediatric IPAA cohort (2.9 years in the pediatric IPAA vs 7.9 years in the pediatric diagnosis-adult IPAA cohort; P < .05). When looking at differences in outcomes, we found that patients in the pediatric IPAA cohort exhibited higher rates of postoperative anti-TNF exposure than patients who were diagnosed with UC as children but underwent surgery as adults (41.5% vs 22.4%; P = .05). The pouch failure rate in the pediatric surgery cohort was not observed to be different compared with those who were diagnosed with UC as children and underwent surgery as adults (18.9% vs 10.3%; P = .31) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in surgical outcomes based on timing of surgery. Differences between groups were determined using a chi-square test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. The left panel shows differences in post-operative anti-TNF use and pouch loss between those subjects undergoing surgery as children compared to adults. The right panel shows these same differences between those undergoing surgery as children compared to those diagnosed as children but not undergoing surgery until adulthood. IPAA, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis; Peds, pediatric; Post Op, postoperative; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Higher Probability of Pouch Failure for Pediatric IPAA in Modern Era

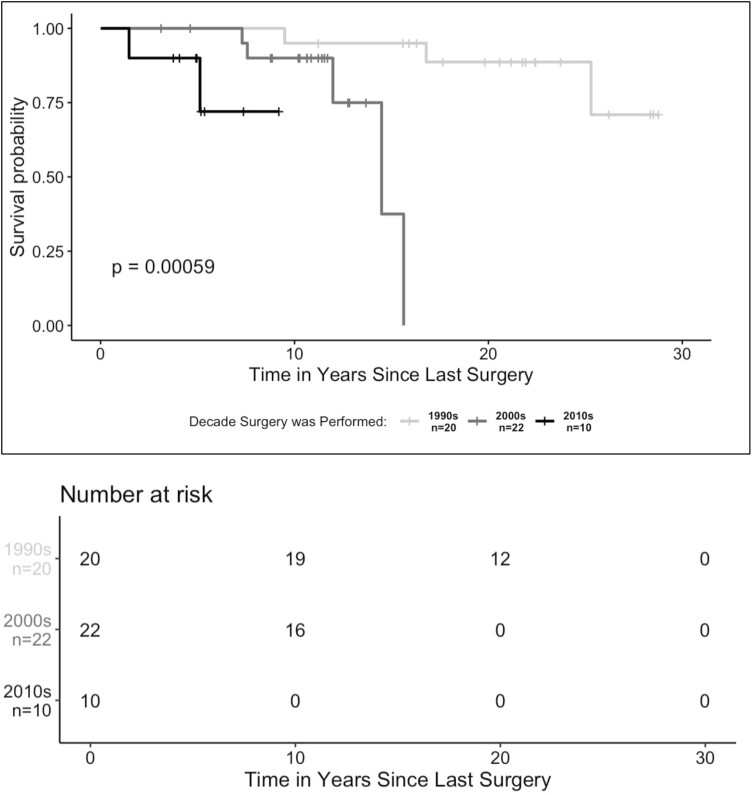

Kaplan-Meier estimates of pouch survival probability revealed that, among patients with UC who underwent IPAA before 19 years of age, those who had their surgeries in more recent decades exhibited higher probabilities of pouch failure. At approximately 5 years postsurgery, the estimated cumulative probability of pouch survival was 72% for surgeries conducted in the 2010s compared with 5-year pouch survival probabilities of 100% for surgeries conducted in the 2000s and 1990s (P < .001) (Figure 2). When we looked at pouch survival probabilities by decade of surgery for both pediatric and adult surgery patients, we found that pediatric IPAA in the most recent decade had the lowest cumulative pouch survival probability (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Pouch survival probability stratified by decade of ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in pediatric surgery patients. For patients who had multistage procedures, observations were classified by decade based on when the first procedure was performed. Differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among Patients Exposed to Anti-TNF Therapy Preoperatively, IPAA in Children Has Lower Pouch Survival Probability

In our cohort, we found that approximately 32% of pediatric patients (n = 17) were exposed to anti-TNF therapies prior to surgery compared with approximately 45% of adult patients (n = 148). Just 1 pediatric subject received vedolizumab preoperatively compared with 14 adults (4.3%), while ustekinumab (n = 2) and tofacitinib (n = 1) were described only in the adult cohort. Anti-TNF therapy precolectomy in pediatric IPAA did not clearly associate with pouch failure (23.5% exposed vs 16.7% nonexposed; P = .83). However, in the adult cohort, a trend toward a lower failure rate was seen in the anti-TNF–exposed group (6.1% vs 12.6% nonexposed; P = .07). The pouch failure rate among anti-TNF–exposed pediatric patients was significantly higher than that of anti-TNF–exposed adults (23.5% vs 6.1%; P < .05).

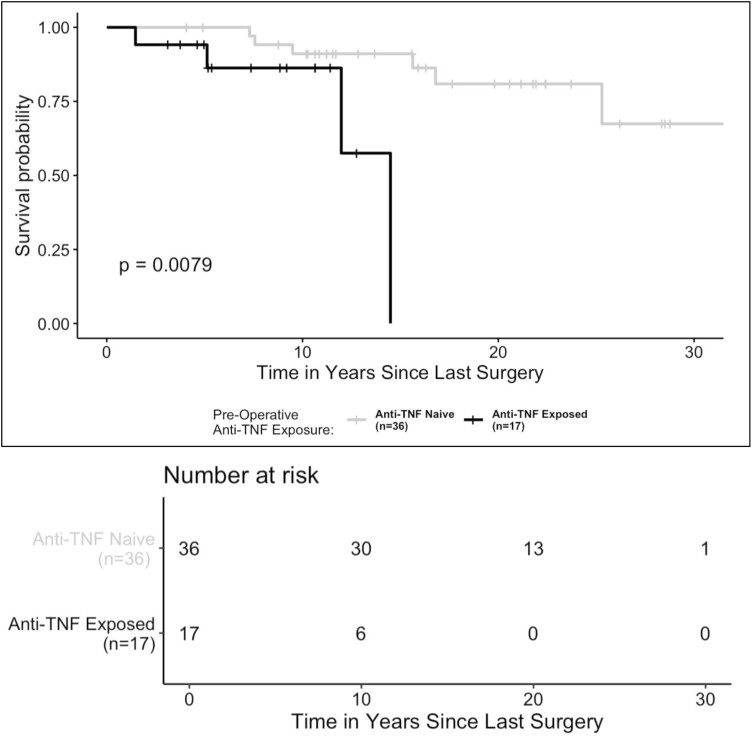

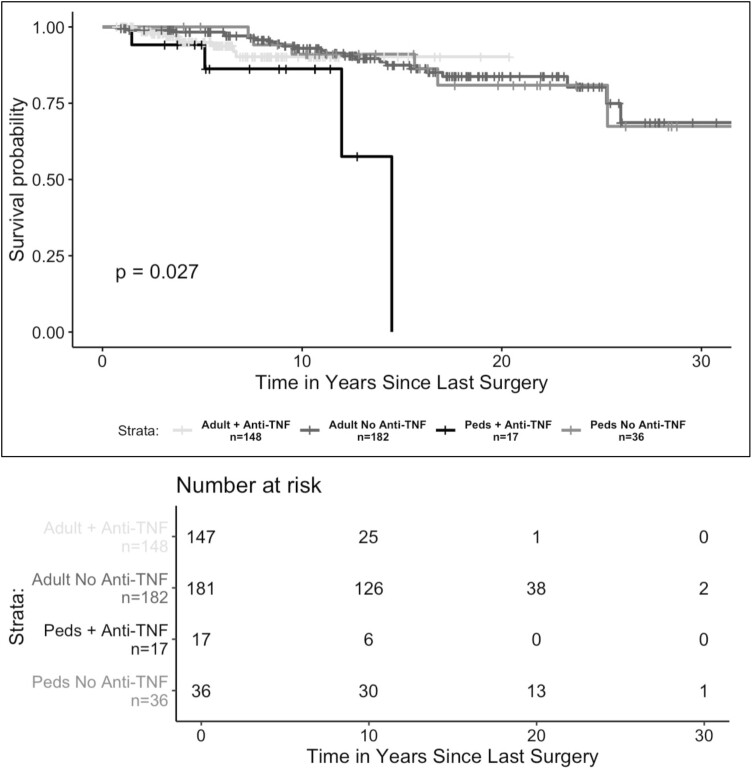

Our Kaplan-Meier estimates of pouch survival probabilities showed that pediatric patients exposed to anti-TNF therapies prior to surgery had a 12-year pouch survival probability that was 33% lower than that of pediatric patients who were anti-TNF naïve prior to surgery (anti-TNF exposed = 58%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 25%-100%; anti-TNF naive = 91%; 95% CI, 82%-100%; P < .01) (Figure 3). When comparing pouch survival probability between pediatric and adult patients exposed to anti-TNF therapies preoperatively, we found that pediatric patients exposed to anti-TNF therapy prior to surgery exhibited the lowest 12-year pouch survival probability (pediatric IPAA + anti-TNF exposed = 58%; 95% CI, 25%-100%; adult IPAA + anti-TNF exposed = 90%; 95% CI, 84%-97%; pediatric IPAA + anti-TNF naive = 91%; 95% CI, 82%-100%; adult IPAA + anti-TNF naive = 91%; 95% CI, 87%-96%; P = .02) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Pouch survival probability in pediatric patients stratified by preoperative exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. Exposure to anti-TNF therapies before surgery was defined as preoperative use of adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, or certolizumab pegol. The presence of pouch failure was defined as the occurrence of a pouch excision procedure. Differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Pouch survival probability in patients with preoperative exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy stratified by timing of surgery. Exposure to anti-TNF therapies before surgery was defined as preoperative use of adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, or certolizumab pegol. Patients were in the pediatric ileal pouch–anal anastomosis cohort if the first stage of their ileal pouch–anal anastomosis was conducted before 19 years of age. The presence of pouch failure was defined as the occurrence of a pouch excision procedure. Differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Peds, pediatric.

Discussion

Here, we offer new insight into IPAA outcomes for children with UC reporting high rates of pouchitis, de novo CD, and pouch loss compared with other retrospective cohorts. Additionally, we consider outcomes based on decade of surgery and exposure to anti-TNF therapy, highlighting differences between pediatric and adult counterparts.

Recent systematic reviews have underscored the efficacy and tolerability of IPAA for children with UC. These studies suggest a pouchitis rate between 30% and 36% with a range of follow-up spanning 5 months to 11 years.9,10 True prevalence may be difficult to estimate, as pouchitis may be defined by symptoms alone, expert opinion, or according to the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index.13 Others have proposed endoscopic definitions such as mucosal erosions and ulcerations, as these features have been shown to precede symptoms.14 Keeping with this method, our definition is anchored by positive findings in the tip or proximal or distal body of the pouch. This may allow for a more objective definition of pouchitis while also increasing sensitivity. The relatively high prevalence (77%) described here aligns closely with results from a recent multicenter cohort that found a pouchitis rate of 67% in 129 pediatric subjects based on clinical symptoms over a 40-month period.15 Future analysis focusing on factors predictive of or conversely protective against onset of pouchitis in children undergoing IPAA are needed to provide patient-families stronger preoperative guidance and may inform surveillance strategies.

These same systematic analyses describe an average pouch failure rate of 6.4% to 10.6% with a median range of follow-up between 4 and 11 years for included studies.9,10 One prospective analysis used questionnaire data from children with UC who underwent IPAA to estimate a pouch loss rate of 8% at 20 years postcolectomy.16 While this cohort included 12.4% who had received anti-TNF preoperatively, this figure was calculated after removing subjects with a postoperative change in diagnosis from UC to CD likely underestimating true pouch failure prevalence. We report a proportionally greater degree of pouch loss at 18.9%, with a median of 14 years of follow-up and a relatively high percentage of children who received anti-TNF therapy precolectomy (32%).

A postcolectomy change in diagnosis from UC to CD is linked to higher rates of pouch failure. This form of IBD is known as “de novo CD of the ileoanal pouch.” While historically this pathologic change has been reported to occur in <10% of subjects with UC17,18 more contemporary analyses have challenged these lower rates with reports as high as 24% to 28% in pediatric cohorts with 13 months to 20 years of follow-up.19-21 One challenge in deciphering prevalence is a lack of consensus regarding the diagnostic criteria of de novo CD.22 In this study, expert opinion guided by clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features over long periods of follow-up also reveal high rates of de novo CD in both the pediatric (38%) and adult (29.8%) cohorts.

One critical factor that be driving higher rates of pouch complications is a change in the paradigm of “medically resistant” UC, with contemporary IPAA subjects having failed anti-TNF therapy in addition to medications used in the previous decades. As detailed in Figure 3, subjects exposed to anti-TNF seem to experience a more rapid progression to pouch loss than pediatric controls who were naive. Additionally, our results show that adults exposed to anti-TNF do not seem to have an accelerated timeline for pouch loss. In fact, the pouch failure rate for the pediatric anti-TNF–exposed group was more than 4 times that of exposed adults.

While we report a more rapid progression to pouch loss following surgery in pediatric subjects exposed to anti-TNF, this does not suggest a causative relationship. The overall impact of anti-TNF therapy on colectomy rates for UC remains unclear. Some studies suggest that the incidence of progression to colectomy in children with UC nationwide has not changed,23 with 1 study finding no difference even as rates of intestinal resection for pediatric CD have decreased.24 Other studies suggests that higher use rates of anti-TNF therapy have lowered the risk of progression to colectomy within 5 years (hazard ratio 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.86)25 and that earlier exposure with optimized dosing may stifle disease progression.26-28

Accounting for the differences in pouch loss observed between children and adults in our decade analysis, one consideration is that pediatric-onset UC presents as a more aggressive phenotype. A recent population-based study comparing outcomes for pediatric (defined as diagnosis <15 years of age) vs adult-onset IBD (defined as >18 years of age) found a more widespread disease at diagnosis and higher rates of exposure to steroids, thiopurines, and anti-TNF therapy for pediatric patients with UC in addition to a more significant risk of relapse.29 Other studies have refuted this notion, with a single-center experience finding no differences in outcomes for younger (defined as 5-12 years of age) and older children (13-18 years of age) who underwent IPAA since 2002, though this cohort included children with FAP, and the percentage who received anti-TNF precolectomy was not reported.30 This raises the possibility that younger age of diagnosis alone does not portend worse postoperative outcomes. We posit that a more rapid progression to colectomy despite anti-TNF therapy marks a fundamentally different phenotype for children with UC and predicts a poorer prognosis for IPAA.

To our knowledge, few other reports have attempted to benchmark differences in IPAA outcomes between children and adults. However, in one such example, researchers considered differences in pouch failure and functional outcomes between a cohort of pediatric (n = 41) and adult (n = 404) subjects who underwent IPAA. This analysis found no statistical differences between groups; however, the cohorts included subjects with IBD and FAP, and preoperative anti-TNF exposure was not reported.31 Similar to the results described here, another head-to-head comparison found higher rates of pouch-related complications and need for postoperative anti-TNF therapy for children who underwent IPAA compared with adults (n = 104 vs adult, n = 1135).32

We did not observe a statistically significant difference in surgical technique between our pediatric and adult cohorts, with 3-stage repair and stapled anastomosis being the most common approach. While the initial description of our database found that these techniques are significantly associated with cuffitis,11 we did not explore here if differences in surgical approach to J-pouch creation may be dictated by patient age or surgical training. However, these questions may bear more consideration in future work, as one retrospective analysis recently reported that operating experience (<10 IPAA procedures per year) may predict worse outcomes.15

This study is limited by the retrospective design and a small number of pediatric subjects who underwent IPAA, acknowledging that nearly 80% of pediatric IPAA procedures are done at centers performing a median of just 3 cases per year.33 As an IBD referral center, it is possible that follow-up for some patients living further from our institution was limited to instances of clinical relapse. Additionally, our database is generated from only those subjects underwent pouchoscopy and therefore may exclude post-IPAA subjects who are clinically well and did not experience complications. Differences in pouch surveillance strategies between pediatric and adult providers may limit direct comparison of these data in certain studies. However, given that all subjects included here were seen within the same IBD Center, this confounding variable would not be expected to influence differences in outcomes.

Given the retrospective nature of this study, the definition of de novo CD was based only on the treating physician’s expert opinion and could not be standardized, a limitation that is consistent with other studies of this kind. Furthermore, our study did not assess clinical symptoms and histologic findings of pouchitis. Finally, incidence of our outcomes of interest may be underestimated in some cases due to loss of continuity of care, even as our average years of patient follow-up remains high.

Conclusions

While more analyses need to be performed to further define prognosis for children with UC undergoing IPAA, we find that pediatric and adult outcomes are different in the era following anti-TNF therapy uptake. Our analysis suggests a more rapid progression to pouch loss for children in the anti-TNF era with high rates of pouchitis and de novo CD. Additionally, children with UC undergoing IPAA in the last 2 decades are more likely to require anti-TNF therapy at any time postoperatively compared with both adults and historical control subjects. Furthermore, for those children moving rapidly from diagnosis to colectomy pouch outcomes seem poor compared with those diagnosed in childhood and not requiring colectomy until adulthood, suggesting that both patient age and length of diagnosis at the time of surgery should be considered in postoperative outcomes. These results indicate that more precise preoperative guidance is needed for patients and their families and that “curative” colectomy for UC may be less common than previously thought. Finally, while prospective work needs to be done to validate these findings and to better understand the forces driving the decline in prognosis over time, rigorous postcolectomy monitoring and surveillance pouchoscopy should be implemented now with the hope that earlier diagnosis of pouch complications may improve outcomes for children following IPAA.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Joseph Runde, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Comer Children’s Hospital, Chicago, IL, USA; University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Amarachi Erondu, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA; University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Shintaro Akiyama, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Cindy Traboulsi, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Victoria Rai, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Laura R Glick, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Yangtian Yi, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA; University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Jacob E Ollech, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Russell D Cohen, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Kinga B Skowron, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Roger D Hurst, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Konstatin Umanskiy, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Benjamin D Shogan, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Neil H Hyman, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Michele A Rubin, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Sushila R Dalal, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Atsushi Sakuraba, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Joel Pekow, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Eugene B Chang, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

David T Rubin, University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: J.R., A.E., S.A., E.B.C., D.T.R. Acquisition of data: J.R., A.E., S.A., C.T., V.R., Y.Y., L.R.G., J.E.O., R.D.C., K.B.S., R.D.H., K.U., B.D.S., N.H.H., M.A.R., S.R.D., A.S., J.P., D.T.R. Analysis and interpretation of data: J.R., A.E., S.A. Drafting of manuscript: J.R., A.E., S.A., C.T., V.R., D.T.R. Critical revision of manuscript: J.R., A.E., S.A., C.T., V.R., N.H.H., E.B.C., D.T.R. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding in part provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P30 DK42086, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases RC2 DK122394, and the GI Research Foundation of Chicago.

Conflicts of Interest

R.D.C. has served on the speakers bureau from AbbVie and Takeda; has served as a consultant/advisor for AbbVie Laboratories, BM/Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB Pharma; and has received clinical trial support/grants from AbbVie, BMS/Celgene, Boehringer Ingelheim, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Hollister, Medimmune, Mesoblast, Osiris Therapeutics, Pfizer, Receptos, RedHill Biopharma, Sanofi, Schwarz Pharma, Seres Therapeutics, Takeda Pharma, and UCB Pharma; and his wife is on the board of directors of Aerpio Therapeutics, Novus Therapeutics, Vital Therapeutics, and NantKwest. M.A.R. has served as a consultant for Pfizer. S.R.D. has served as a consultant for Pfizer and on the speakers bureau for AbbVie. J.P. has received grant support from AbbVie and Takeda; served as a consultant for Veraste and CVS Caremark; and served on the advisory board for Takeda, Janssen, and Pfizer. E.B.C. is the founder and chief medical officer of AVnovum Therapeutics. D.T.R. has received grant support from Takeda; has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Abgenomics, Allergan, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bellatrix Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corp/Syneos, Check-cap, Dizal Pharmaceuticals, GalenPharma/Atlantica, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Ichnos Sciences, InDex Pharmaceuticals, Iterative Scopes, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Lilly, Materia Prima, Narrow River Mgmt, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories, Reistone, Takeda, and Techlab; is co-founder of Cornerstones Health, and GoDuRn; and has served on the Board of Trustees of the American College of Gastroenterology. The other authors have no relevant disclosures.

References

- 1. Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS.. Ulcerative colitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1553-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turner D, Levine A, Escher JC, et al. Management of pediatric ulcerative colitis: joint ECCO and ESPGHAN evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(3):340-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hwang JM, Varma MG.. Surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2678-2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan Tanny SP, Yoo M, Hutson JM, et al. Current surgical practice in pediatric ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1324-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kayal M, Plietz M, Rizvi A, et al. Inflammatory pouch conditions are common after ileal pouch anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1079-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Germain A, Patel AS, Lindsay JO.. Systematic review: outcomes and post-operative complications following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:807-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:679-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sherman J, Greenstein AJ, Greenstein AJ.. Ileal J pouch complications and surgical solutions: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1678-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drews JD, Onwuka EA, Fisher JG, et al. Complications after proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in pediatric patients: a systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1331-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lightner AL, Alsughayer A, Wang Z, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes after ileal pouch anal anastomosis in pediatric patients: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1152-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akiyama S, Ollech JE, Rai V, et al. Endoscopic phenotype of the J pouch in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a new classification for pouch outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online February 5, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kayal M, Plietz M, Radcliffe M, et al. Endoscopic activity in asymptomatic patients with an ileal pouch is associated with an increased risk of pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:1189-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Orlanski-Meyer E, Topf-Olivestone C, Ledder O, et al. Outcomes following pouch formation in paediatric ulcerative colitis: a study from the Porto group of ESPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;71:346-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Polites SF, Potter DD, Moir CR, et al. Long-term outcomes of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for pediatric chronic ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1625-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hyman NH, Fazio VW, Tuckson WB, Lavery IC.. Consequences of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for Crohn’s colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:653-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ Jr, Roberts PL, et al. Evolutionary changes in the pathologic diagnosis after the ileoanal pouch procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:263-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jarchin L, Spencer EA, Khaitov S, et al. De Novo Crohn’s disease of the pouch in children undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;69:455-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones I, Ramani P, Spray C, Cusick E.. How secure is the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis in children, even after colectomy? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shannon A, Eng K, Kay M, et al. Long-term follow up of ileal pouch anal anastomosis in a large cohort of pediatric and young adult patients with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:1181-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lightner AL, Pemberton JH, Loftus EJ Jr. Crohn’s disease of the ileoanal pouch. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1502-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Debruyn JC, Soon IS, Hubbard J, et al. Nationwide temporal trends in incidence of hospitalization and surgical intestinal resection in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases in the United States from 1997 to 2009. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2423-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ashton JJ, Borca F, Mossotto E, et al. Increased prevalence of anti-TNF therapy in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease is associated with a decline in surgical resections during childhood. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:398-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larsen MD, Qvist N, Nielsen J, et al. Use of Anti-TNFα agents and time to first-time surgery in paediatric patients with ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:650-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lega S, Phan BL, Rosenthal CJ, et al. Proactively optimized infliximab monotherapy is as effective as combination therapy in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:134-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bolia R, Rajanayagam J, Hardikar W, Alex G.. Impact of changing treatment strategies on outcomes in pediatric ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1838-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh N, Rosenthal CJ, Melmed GY, et al. Early infliximab trough levels are associated with persistent remission in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1708-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malham M, Jakobsen C, Vester-Andersen MK, et al. Paediatric onset inflammatory bowel disease is a distinct and aggressive phenotype—a comparative population-based study. GastroHep. 2019;1(6):266-273. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bismar N, Patel AS, Schindel DT.. Does age affect surgical outcomes after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in children? J Surg Res. 2019;237:61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diederen K, Sahami SS, Tabbers MM, et al. Outcome after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in children and adults. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1640-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu XR, Mukewar S, Hammel JP, et al. Comparable pouch retention rate between pediatric and adult patients after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouches. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1295-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Egberg MD, Galanko JA, Kappelman MD.. Patients who undergo colectomy for pediatric ulcerative colitis at low-volume hospitals have more complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(13):2713-2721.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.