Abstract

objective:

This investigation explored the barriers and facilitators to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in the integrated paradigm.

methods:

A search technique for barriers and facilitators of SUD treatment was applied to the PubMed and Web of Science databases to identify relevant systematic reviews. The eligibility criteria included systematic review (SR) or SR plus meta-analysis (MA) articles published before the end of 2021, human research, and the English language. Each of the 12 relevant review articles met the inclusion criteria. AMSTAR was utilised to evaluate the methodological quality of the systematic reviews.

results:

Two authors analysed 12 SR/SR-MA articles to identify barriers or facilitators of SUD treatment. The cumulative summary results of these 12 evaluations revealed that barriers and facilitators may be classified into 3 levels: individual, social and structural. By analysing these review papers, 37 structural barriers, 21 individual barriers and 19 social barriers were uncovered, along with 15 structural facilitators, 9 social facilitators and 3 individual facilitators.

conclusions:

The majority of barriers indicated in the review articles included in this analysis are structural, as are the majority of facilitators. Consequently, the design of macro models for the treatment of substance use disorders may yield various outcomes and potentially affect society and individual levels.

Keywords: Barrier, facilitator, substance use disorder, treatment, review

Introduction

Substance use is one of the most expensive health issues.1-5 The projected overall cost of substance use treatment in the United States in 2003 was $21 billion, of which 77% was paid for by public sources, 6 and the problem is not restricted to the United States.7,8 Substance use impacts numerous facets of a person’s life and making therapy complex. 3 Unfortunately, many consider treatment a failure when relapse occurs. Similar to other chronic disorders, SUD is characterised by alternating periods of abstinence and use, or recovery and relapse. 9 Like other chronic disorders, SUD can be effectively controlled. 3 The high expenses associated with substance use include health care, costs related to crime, lost employment, decreased productivity, social and familial damage and overdose deaths. The capacity of existing inpatient and outpatient services falls short of the rate of demand. 10 And the ratio of untreated to treated individuals ranges from 3:1 to 13:1. 11 These results should assist in identifying and addressing obstacles to treatment.

Numerous studies have highlighted impediments to substance use treatment. The results of more than 4 decades of research into the barriers and facilitators of substance use show these factors are very diverse. Reviews studies based on large body of original articles have listed these factors from micro to macro levels. And the number of systematic reviews that have been published on barriers to substance use treatment is expanding. While we cannot really conclude which level is more significant. Maybe because each of these review studies has focused on a one type of drug for example barriers to methamphetamine treatment, 12 or barriers to opiate treatment, 13 barriers to alcohol treatment 14 or factors influencing the treatment of substance use disorders in specific group for example women, 15 mothers, 16 prisons 17 and etc. or barriers due to role of management system or role of peers 18 and so on.

Healthcare providers of SUD treatment or policy makers are faced with many reviews studies on a challenging topic that find it hard to reach a result without conflicting based them. They need a technique that can organise various information to coherently comprehend current state. Appropriate perception of the problem leads to planning the effective approaches for intervention or any action. 19 So, the current study is intended to try to develop an integrated conclusion by reviewing systematic review studies on barriers of facilitators of SUD treatment.

Method

Search strategy

The following search technique was developed and implemented in the PubMed and Web of Science databases. The word for the search technique was debated and agreed upon by the study advisory group.

(treatment OR management OR therapy OR pharmacotherapy OR psychotherapy OR intervention OR ‘Group therapy’ OR ‘Psychosocial interventions’ OR ‘Narcotic Anonymous’ OR ‘Alcoholic Anonymous’ OR withdrawal OR detoxification OR residential OR methadone OR buprenorphine OR agonist OR maintenance OR substitution) AND (substance OR drug OR opioid OR opiate OR opium OR morphine OR codeine OR methadone OR narcotic OR Heroin OR Alcohol OR Amphetamine OR methamphetamine OR benzodiazepine OR hallucinogen OR marijuana OR cannabis* OR cocaine OR phencyclidine OR sedative OR tranquil* OR solvent OR inhalant OR psychotropic) AND (abuse OR dependence* OR use OR disorder OR addict* OR misuse OR harmful) AND (barriers OR facilitators OR obstacles OR availability OR intake OR Access* OR coverage OR retention OR adherence) AND (‘Systematic review’ OR meta-analysis)

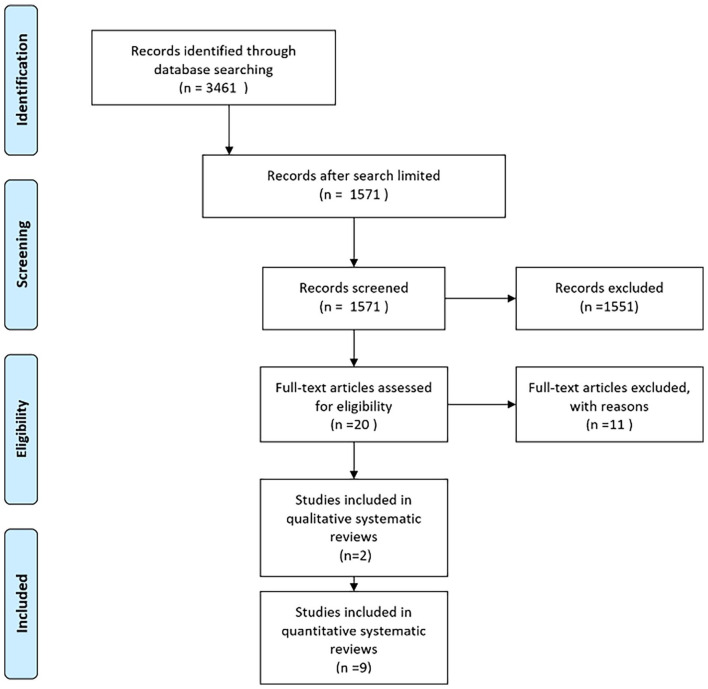

The search discovered 3461 articles that were consistent with the search strategy. When we restricted our search to human research and SR/SR-MA papers, the number of results dropped to 1571. In the subsequent stage, the titles and abstracts of the retrieved citations were separately evaluated by 2 reviewers (ZH and AP), and grey articles were omitted. Other authors (ER, AF, ARN) arbitrated disagreements and 20 SR/SR-MA or review (R) publications were selected for full-text screening. Two reviewers (ZH and AP) independently assessed potentially relevant SR/SR-MA publications that investigated the barriers or facilitators of SUD treatment to find acceptable studies for data extraction; ultimately, 12 review articles (included 526 primary articles) were included. The study’s flowchart is depicted in Figure 1. The 2 authors then extracted data using the data collecting form. To settle any misunderstanding or dispute, the writers employed a discussion-based approach. Table 1 contains an overview of each study’s major data and findings.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram to systematic reviews selection.

Table 1.

Summary table of the scope of reviews in a systematic review of reviews.

| Author and year of publication | Aim and participants | Sources or database of search | N studies | Type of review | Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barnett et al16 | To help systems and providers understand the facilitators of and barriers to treatment for mothers with substance use disorder who are pregnant or parenting young children in the United States and Canada | Ovid-MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL and ProQuest Dissertations for texts published between 2000 and 2019 | 23 | Systematic review | High |

| 2 | Grella et al17 | Identify barriers and facilitator of implementation of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder within criminal justice settings and with justice-involved populations | PubMed, PsycINFO, National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts (NCJRS) and the Cochrane Library | 24 | Systematic review | High |

| 3 | Sarkar et al23 | This study aimed to synthesise the literature on barriers and facilitators of treatment in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) | MEDLINE | 28 | Qualitative review synthesis | Medium |

| 4 | Choi et al25 | To findings on gateways, facilitators and barriers to treatment for pregnant women and mothers with SUD | MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar | 41 | Systematic review | High |

| 5 | Marshall et al18 | How programmes are organised, and the obstacles and facilitators to engaging people with lived experience in harm reduction programmes. The objective was to identify and synthesise information that could inform person who use drug organisations, service providers who work with peers in harm reduction initiatives, policymakers and those hoping to better engage people with lived experience in the delivery of harm reduction services. | Web of Knowledge, Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, CINAHL and PubMed | 164 | Systematic review | Medium |

| 6 | Kelly et al14 | What issues (context, barriers and facilitators) prevent or limit, or help and motivate the prevention or reduction of excess alcohol consumption in people in older age (55+ years)? | MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, CENTRAL, Social Sciences Citation Index, York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Cochrane database and grey literature | 14 | Systematic review | High |

| 7 | Lagisetty et al24 | (1) Identify thematic components of primary care OUD MAT models that are accepted by patients and physicians and associated with improved health outcomes | PubMed, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO | 41 | Systematic review | Medium |

| (2) Use those findings to guide future policy and provide recommendations on design features of delivery models found to be effective in the primary care setting | ||||||

| 8 | Cumming et al12 | Identifying most commonly reported barriers to access methamphetamine treatment across government and non-government agencies in planning new services and adapting existing services | Scopus (Sciverse); MEDLINE (Ovid); PsycINFO (ProQuest); Web of Science (Web of Knowledge); and PubMed | 11 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | High |

| 9 | Timko et al13 | To identify factors associated with the outcome of retention in medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opiate dependence | PubMed | 55 | Systematic review | Medium |

| 10 | Notley et al26 | Aims were to explore qualitatively reported barriersto recovery, with barriers defined as circumstances or obstacles that impede progress towards recovery | Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (Ovid) and MEDLINE (PubMed) | 14 | Qualitative systematic review | Medium |

| To inform understanding of the experience of long-term opiate maintenance and identify barriers to recovery | ||||||

| 11 | Johnson et al22 | Synthesise qualitative evidence for barriers and facilitators to effective implementation of screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse in adults and children over 10 year | MEDLINE via OVID; CINAHL via OVID; PsycINFO via OVID; ASSIA via CSA and the Social Science Citation Index and Science Citation Index via Web of Knowledge | 47 | Systematic review of qualitative evidence | Medium |

| 12 | Sun15 | This study examined programme factors related to women’s SUD treatment outcomes | PubMed of the National Library of Medicine, Social Work Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, PsycINFO and ERIC | 35 | Systematic review | Medium |

Articles published through the end of 2021 that were written in English, focused on humans, and were either reviews, systematic reviews or meta-analyses. The results revealed SUD treatment obstacles and facilitators. Applying the following exclusion criteria: In lieu of finding barriers or facilitators of SUD treatment, this review examines comparable animals whose recovery or relapse has been researched in terms of influencing factors.

Quality assessment of review’s studies

Smith et al 20 have introduced an assessment tool to quality assessment of systematic reviews systematically. Assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews (AMSTAR) has been validated to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews and may be used in the evaluation of reviews to determine if potentially eligible reviews meet quality-based eligibility requirements. AMSTAR assessment criteria were utilised to evaluate the methodological quality of the reviews. The review papers were deemed ‘high quality’ if they included evidence of their search technique, inclusion criteria, evaluation of publication bias and evaluation of heterogeneity in methodology or outcomes. If all of these evidences were present, but evidence for evaluating publication bias or heterogeneity was unavailable, the review study would be regarded to be of ‘medium quality’. And the evaluation was deemed to be of ‘poor quality’ if there was evidence of a search strategy but no other criteria. Each evaluation was individually allocated to a single reviewer, and the result of the quality assessment was confirmed by discussion with other reviewers.

Checking for Primary Article Overlapping Across the Reviews

This overview was going to identify and synthesise systematic reviews on the barriers and facilitators of SUD treatment, so it was likely to be duplicated or overlapped in primary studies across the reviews. 21 Overlap is a problem of precision related to sampling (ie, it is not a bias). If the one primary study is included in more than one systematic review and if we use those reviews, we overstate in the results or factors that root in the primary study. Here precision of study may be impacted that is related to sampling. The authors listed the primary studies of each systematic review in the excel file (first column included the authors name and publication year of primary studies and second column included review studies that had used primary study), then we sorted first column according name of authors from ‘A to Z’. Therefore, primary studies that were duplicates and were used in more than 1 review were identified. There were only 4 initial studies used in more than 1 review study, which are as follows: Johnson et al 22 and Kelly et al 14 had a one common primary study. Grella et al 17 and Sarkar et al 23 also had a one common primary study. Timko et al 13 and Lagisetty et al 24 had 2 common primary study. In other words, the overlap was less than .01 among the primary 526 articles that were the basis of the 12 review studies.

Ethic

This review’s study is a part of the study No. 964026 that research protocol was approved by the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) by ethical code: IR.NIMAD.REC.1397.268.

Results

Tables 2 and 3, illustrate the cumulative summary results of these 12 review studies. The results were divided into 3 categories: the individual, societal and structural levels. These levels may not be considered independent of one another despite their apparent simplicity. The preliminary results were extracted and then the codes and classifications were agreed upon in a number of meetings. The data in Table 1 has been utilised to comprehend Tables 2 and 3. At each mention of a barrier, a reference number is provided. These are the codes of review studies in the first column of Table 1.

Table 2.

Summary of results reported in systematic reviews for barriers of SUD treatment.

| Level | Barriers a |

|---|---|

| Individual | Wrong belief about treatment: Belief that treatment was unnecessary (3, 8), preferring to withdraw alone without assistance (2, 8), beliefs about methadone (2, 10) |

| Perceived fears: Fear of incarceration (4), Fear of stigma (4), Fear of inconvenience (4), Fear of loss custody of children (for mothers) (4), Fear of suspension or termination of parental rights (4), Fear of withdrawal symptoms (10), Fear of life without the stability and routine of taking methadone (10) | |

| Personal traits: Low self-esteem (10), Individuals’ self-concepts (10), Low self-confidence (10), Identity difficulties (10), Privacy concerns (2, 3, 8), Loneliness (10), Motivational factors (1, 3, 8, 9, 10). Poor coping styles to deal with difficulties (1, 5, 6) problem with emotional management (1, 10). | |

| Psychiatric comorbidities: (1, 3, 10) | |

| Social | Stigma and lack of social support: Embarrassment or stigma (1, 2, 5, 8), Lack of social capital or social support (1, 3, 4, 5, 8), Not having anything else going on in one’s life (10) |

| Family factors: Influence of habits of spouse/partner/family members/peers to drugs (6), Partner dropped out (10), Partners violence (10), No supportive family (1) | |

| Friends network: Non supportive friends (1), Difficulties with establishing a non-drug using network of friends, and severing ties with existing drug-using networks (10), Over-reliance on other clients (10) Secrecy or fear about the past in new interpersonal relations (10), Negative role model (10), Lack of models who have successfully recovered (10) | |

| Problems with a therapeutic team: None emphatic relationship from treatment staff (1, 2, 3, 4, 11), Poor therapeutic relationship between patients and practitioner (11), Tensions between peer workers and programme staff (5), Wrong belief about people who use drug among therapeutic team(5), Very dependent relationships with treatment staff (10), Clients’ passivity in accepting staffs’ attitudes (10) | |

| Structural | Problems related to treatment provider services: Insufficient places (1, 2, 3, 8, 11), Waiting lists/times (2, 8, 11), Unsuitable/ineffective services for people with mental illness (1, 4, 8), Expensive costs and financial problems (8, 9, 11), Lack of available ancillary psychosocial services (10), Staff attitudes service providers (8), Lack of training in both nurses and General physicians(GPs) (11, 2), Lack of appropriate skill for non-physician team members for high-quality care (2, 10), A lack of primary care SUD fellowship (10), Lack of connection between emergency care and professional medical treatment (5). Insufficient training and support for peers (5) Lack of availability of peer workers (5), Lack of suitable treatment system for both genders (1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12), Ideology of treatment (9), Treatment intensity (10), Clinical inertia among nurses (11), GPs attitude to drug or alcohol (6), Therapeutic impasse (10), Failure to ground programming in the lived experiences of person who previously used drug (1, 2, 5), Lack of qualified workforce (2), The lack of appropriate treatment protocols (2), The preference for a forced detoxification approach instead of medical approach in some setting such as correctional-educational environments (2), Lack of adherence to treatment protocol (2). |

| Legal barriers: Restrictive policies (lack of a legal structure for various organisational relationships, such as prisons and medical settings that patients could follow their treatment) (2), Implications for child custody arrangements for parents who use drug or alcohol (8), Misuse of prescribed medications (7, 10), Prescription challenges (10). | |

| Policy barriers: Exclusionary attitudes, policies and programmes (5), Policies which favour enforcement rather than harm reduction (5), Lack of focus on vulnerable sub-communities despite identified needs (5), No decision-making lived experiences of person who us drug (5) Failing to address social determinants of health (5), No considering contextual factors (5), Lack of focus during outreach on housing, jobs (5), The continued criminalisation of drug use (and people who use drugs) (5), Policies that favour enforcement (5, 1), Lack of linkage or coordination between correctional and community medications for treatment of opioid use disorder (MOUD) treatment providers (2). |

The below numbers in front of each facilitator refer to the first column, article number, in Table 1.

Table 3.

Summary of results reported in systematic reviews for facilitators of SUD treatment.

| Levels | Facilitatorsa |

|---|---|

| Individual | Personal motivation: Establishment of a non-addict identity (10), Personal motivation (1, 4, 5) |

| Social | Family: Supportive family (3) |

| Friends: Influential safe peers (5), Safe model of peers (5), Supportive friends (1, 4) | |

| Treatment team: A supportive and confidential individual counselling approach and Trusting relationship with the treatment team (1, 2, 4, 9, 12) | |

| Structural | The setting of treatment provider services: Training of key skills for creating an opportunity for children to be with parents (for mothers) (1, 2), Availability of effective treatment (3, 12), Appropriate context for discussion (11), Open communication between the NCM and SUD counsellors (7), Training for GPs and staff (3, 11, 7), Access to financial support (3, 4, 10, 7), Peer involvement in the governance and management of the programme (5), The direct participation of people who use drugs as outreach workers (5). |

| The logistic of treatment programme: Implementation of prior experiences and management stability (11), Multidisciplinary and coordinated care delivery models (7), Employ clinical pharmacists for medication dosing management (11), Developing systems that provide care & feedback for patients (11), Home induction helping (11), Case management, & counselling for complicated patients (11), The use of culturally relevant programming (5), Flexible models of service delivery which are open to change (5), The inclusion of structural interventions which address broader issues (5), Women-only programme for females (12), Residential treatment (12), Providing child care (1, 4, 12), Intensive case management and aftercare support (12) | |

| Policy and other organisation: A positive relationship between the institution and the broader community, political support, policy support and recognition as a valuable organisation by local health authorities (5), Peer influence and social networks; providing training and support to peers in their work (5), Successful harm reduction programmes (5) The leadership of peers in promoting health fosters behaviour change (5), Hiring female peer outreach workers to specifically target vulnerable populations (5), Offering women-friendly outreach kits and referrals to female-specific services (5), Police support (5). |

The below numbers in front of each facilitator refer to the first column, article number, in Table 1.

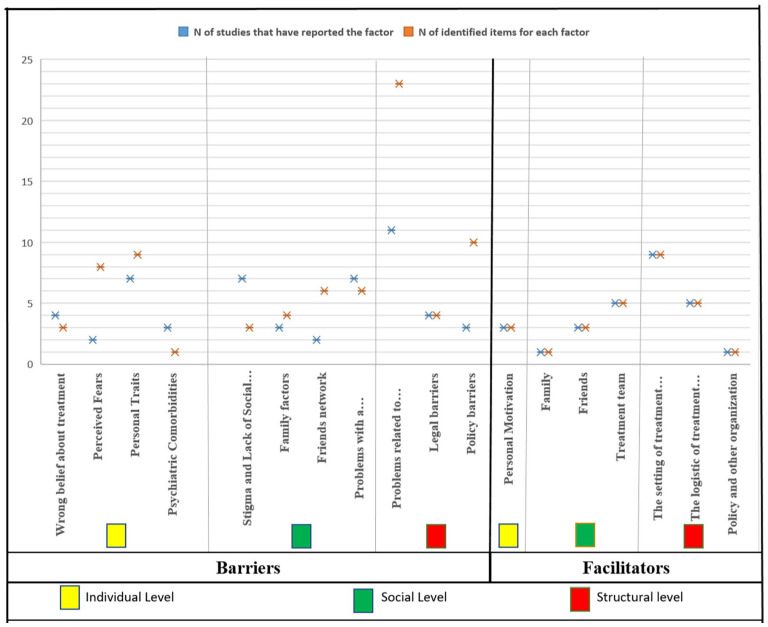

Figure 2 represents the compressed results of barriers and facilitators to SUD treatment. Overall, cumulative results of review studies show there are 21 individual barriers, 19 social barriers and 37 structural barriers to SUD treatment, we also recognised 3 individual facilitators, 9 social facilitators and 15 structural facilitators to SUD treatment.

Figure 2.

Overall barriers and facilitators of SUDs treatment in 3 level.

Barriers

In the individual levels 4 main factors were extracted, each of which contains detailed items. Wrong belief about treatment was reported in the 4 study that include 3 items. Perceived fears were reported in 2 studies that include 8 items. Personal traits were reported in the 7 studies that include 9 items. Psychiatric comorbidities was reported in the 3 study that is a single item. At the social level, 4 main factors were extracted with detailed items. Stigma and lack of social support were reported in the 7 studies that include 3 items. Family factors were reported in the 3 studies that include 4 items. Friends network was reported in the 2 studies that include 6 items. Problems with a therapeutic team were reported in the 7 studies that include 6 items. At the structural level, 3 main factors were extracted with detailed items. Problems related to treatment provider services were reported in the 11 studies that include 23 items. Legal barriers were reported in the 4 studies that include 4 items. Policy barriers were reported in the 3 studies that include 10 items.

Facilitators

At the individual level, 1 main factor was extracted and it was personal motivation that was mentioned in the 3 studies with 3 items. At the social level, 3 main factors were extracted, each of which contains more items. Family factors were mentioned in the 1 study. Friends network was mentioned in the 3 studies that include 3 items. The treatment team was mentioned in the 5 studies that include 5 items. At the structural level, 3 main factors were extracted, each of which contains more items. The setting of treatment provider services was mentioned in the 9 studies that include 9 items. The logistic of the treatment programme was mentioned in the 5 that include 5 items. Policy and other organisations were mentioned in the 1 study.

Here are the outcomes of each systematic review included in the current reviews:

Barnett et al 16 by analysing 23 studies published in 2021, discovered 3 categories of facilitators and hurdles to addiction treatment: internal factors, relational factors and structural barriers. The most influential internal factors were mothers’ motivation to be good mothers, to change their children’s lives and to maintain custody of their children. The most inhibiting internal factors were mothers’ fear of losing custody of their children or being away from the child due to treatment, perceived stigma and the fear of asking for help. In terms of relational aspects, helpful, trustworthy and respectful connections with health care providers, friends and family members were the most influential. Among the obstacles to these characteristics were a lack of knowledge and empathy for health care providers, unsupported sexual partners, controlling families and unsupportive friends. Among the structural elements, some aspects of the systems, institutes or treatment programmes were highlighted as facilitators, such as the programme flexibility and discipline, the provision of various services such as mental health or parenting training courses, and life skills training. The most frequently cited structural hurdles were childcare issues, a mismatch between treatment programmes and the mother’s role; absence of treatment plans for expectant mothers; lack of insurance coverage; unavailability of treatment; hospital regulations or legal restrictions.

Grella et al 17 identified 4 characteristics that facilitate or impede the implementation of drugs for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the criminal justice system after examining 53 studies. Institutional constraints include inadequate capacity, lack of a skilled workforce and restricted policies, particularly for pregnant women and patients with chronic pain. The programme factors include the absence of appropriate treatment protocols; the preference for a forced detoxification approach over a medical approach; the use of lower doses of prescribed methadone; and the absence of adequate withdrawal management; abstinence orientation/correctional environment; a lack of skills, time, knowledge and interest on the part of physicians; a lack of institutional support, resources and nurses. Attitudinal variables pertain to negative views about the medications for treatment of opioid use disorder (MOUD) and the desire for abstinence-based treatment among judicial system participants, personnel and key stakeholders. A lack of treatment capacity, both in prison and in the community at the time of release, is a systemic concern a lack of link or agreement between community MOUD treatment providers and the penal system.

Sarkar et al 23 was able to uncover a large array of obstacles and enablers by analysing the results of 28 qualitative studies. Perceived lack of issues or lack of need for treatment, as well as a lack of desire, were the most often reported barriers, whereas strong family support and accessibility to competent treatment were cited as facilitators. Other obstacles included the shame and stigma associated with substance misuse, the difficulty of getting assistance, the high expense of therapies and medications, the limited availability and variety of programmes and worries around confidentiality.

Choi et al 25 analysed 41 publications and determined that social service providers, criminal justice settings, community organisations and employers can provide health care services. Fear of incarceration, fear of stigma, charges of child abuse, inconvenience and financial difficulty, fear of losing children and suspension or termination of parental rights were cited as barriers for pregnant women and mothers with SUD. Some variables, including emotional or social support and the prospect of reuniting with children, prompted women to seek treatment.

Cumming et al 12 study comprised of 11 publications and 1866 participants that sought to identify the most often reported impediments to methamphetamine treatment access. The most frequently reported barriers identified by this review study are the belief that treatment is unnecessary or a preference to withdraw alone without assistance, a lack of motivation, privacy concerns, embarrassment or stigma, a lack of social capital, implications for child custody arrangements, insufficient places, waiting lists and times, affordability and cost, unsuitable/ineffective services for women and people with mental illness and staff attitudes among service providers.

Johnson et al 22 analyses and synthesises qualitative data from 47 articles and 43 854 participants, addressing hurdles and enablers to the effective implementation of screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse and use in adults and children older than 10 years. This study identifies the following barriers: anxiety about misguidance from nurses; little time was spent discussing alcohol consumption with people who use alcohol; the General physicians’ (GP) relationship with alcohol; the relationship between those who use alcohol and practitioners; the appropriate context for discussion; lack of training in both nurses and GPs; access to financial support; advice is more likely to be given to certain groups, such as men; the setting is unsuitable.

Kelly et al 14 the study analysed 14 papers and 1727 participants to address the following question: what factors (context, barriers and facilitators) impede or encourage the reduction of excessive alcohol consumption in older adults (55+ years)? Fear of falling or appearing foolish; drinking to cope with difficulties, for example, social isolation, illness, loss of physical health or mobility; bereavements such as loss of partners, family or friends; the influence of drinking habits of spouse/partner/family/peers; maintaining longer relationships with grandchildren and great-grandchildren; alcohol as a connection to earlier life; GPs as not wanting to treat drinkers, or did not see drinkers; and alcohol as a connection to earlier life.

Lagisetty et al’s 24 study reviewed 41 articles with 7800 subjects to identify thematic components of primary care opioid use disorders (OUD) medication-assisted treatment (MAT) models that are accepted by patients and physicians and associated with improved health outcomes. According to their findings, open communication between the nurse care manager (NCM) and SUD counsellors enhanced patients’ adherence to SUD treatment in the treatment context. Psychiatric comorbidity, lack of primary care SUD fellowship, lack of specific education about this patient and lack of appropriate supplementary psychosocial therapies are obstacles. Expenses of the clinic; difficulties associated with prescribed medications; high staffing costs; efforts to limit the misuse of prescription medications; the distribution of pharmacies and the provision of an empathic atmosphere without stigma for patients are barriers to care. The findings indicate that multidisciplinary and coordinated care delivery models are an effective strategy to treat OUDs and make it simpler for patients to receive MAT in primary care.

Marshal et al 18 reviewed 164 articles with the aim of examining how the lived experience of people can apply to organising programmes for harm reduction. This reviewed study addressed a number of obstacles, such as the unavailability of peer educators for one of the following reasons: arrest, drug or alcohol use, competition for financial interests and relapse anxiety. The factors that facilitated treatment were culturally relevant programmes, notification of the financial ramifications of treatment, flexible programmes and their accessibility. Working with peers was shown to involve the following factors: debriefing meetings to help peer workers by staff, establishing norms and responsibilities to address situations in which expectations are breached. Activities that bolster the volunteer’s motivation and provide time for peer collaboration. Individuals contain 2 facilitators: acceptable risk for norm transformation and effective peers who change community norms via social network effects. And obstacles include the requirement for safer peers to serve as role models, inadequate training or lack of readiness among peers and a lack of conflict management between programme staff and peer workers. The misconception that person with substance use disorder lack the ability to organise themselves or are incapable of addressing societal issues is false. Barriers related to systemic factors were grouped into 3 main categories: continued criminalisation of substance use (and to find guilty people who use drugs); support enforcement policies rather than harm reduction; and stigmatisation of drug use and people who use drugs, which led to a lack of programme or public support. While healthy interactions between diverse institutions and the larger community are essential, supporting policies, political support and recognition as a useful organisation have all been identified as facilitating peer programming.

Sun’s 15 examined programme characteristics associated with the treatment results for women with SUD by analysing 35 studies involving 22 356 participants. This review study concluded: that female dropouts when their male partner dropped out, trusting relationships with the treatment team, encouraging them to use a wide range of services and preventing dropout, staff supportiveness and/or the availability of individual counselling were positively associated with better treatment outcomes, individual counselling offered by a nonjudgemental counsellor appears to add a special benefit for women, intensive case management a special benefit for women and intensive case management a special benefit for women. Lastly, a supportive and discreet individual counselling approach may be more successful than a group counselling session in addressing women’s feelings of shame, guilt and inadequacy.

Notley et al 26 examined qualitatively reported barriers to recovery, where barriers were defined as ‘circumstances or hurdles that impede recovery progress’ and 14 articles with 1265 subjects were reviewed. The reduction of methadone was viewed as exceedingly challenging by both staff and clients, particularly in terms of dealing with psychological challenges, emotions of loss (of the ‘crutch’ of methadone), anxiety, life pressures and the resurfacing of feelings. Fear of withdrawal symptoms was also a factor in the incorrect diagnosis of mental disorders among person with substance use disorder, which may be a factor in recovery failure and relapse. Fear of a life without the routine and stability of methadone also worked as a barrier to rehabilitation. Establishing a non-addict identity is essential for attaining recovery. Relapse is connected with difficulties in building a non-drug-using network of friends, severed relationships with current drug-using networks and unfavourable role models. Having no other activities in one’s life was also highlighted as a barrier to healing. Multiple stigmas may constitute a formidable barrier to healing. Others have discussed the interrelationships between social class and status; self-perceptions may also connect with the sense of stigma. The structural concept of a ‘therapeutic impasse’ may be an impediment to rehabilitation, as clients and staff may pursue different objectives. When a customer is ‘not ready’ for recuperation, it is a barrier.

Timko et al 13 comprised 55 publications, and 27 131 participants discovered characteristics linked with the outcome of opiate dependence medication-assisted treatment (MAT) retention. Cost and ideology, such as physicians’ opinions that Contingency Management (CM) does not treat the underlying causes of SUD or undermines a patient’s own motivation for abstinence, were found to be the primary hurdles to the use of CM.

Discussion

This review article addressed barriers to SUD treatment based on the findings of prior reviews and attempted to provide a comprehensive picture of these issues. Each of the extracted barriers has a significant impact on SUD treatment, and their interplay exacerbates this effect. According to the data (Figure 2), the majority of barriers and facilitators are structural, followed by social, and then individual.

False ideas are one of the obstacles to treatment for individuals. Some SUD patients believe, for instance, that ‘I can withdraw on my own’ or that ‘the previous medication was replaced with methadone, a new addictive medicine’. Why do so many individuals with substance use disorders expose their problems to loneliness? 84% of persons with alcohol problems believe they do not have significant difficulties, 96% believe they can handle it on their own and 56% have no desire to seek the necessary help, according to a study of the general population. Similarly to Person with alcohol use disorder, person with heroin addiction have cited similar motivations for their behaviour. 12 We believe stigma plays a key role in treatment-seeking delays, as it decreases the likelihood that a psychiatric patient would seek treatment. 27 They dislike being perceived as weak individuals who require assistance from others, especially professional assistance. 28 Some of them fear that others would discover their mental health issues and act improperly. 29 They dislike considering their identity as a patient undergoing treatment for addiction.30,31 They favour denying their concerns. Notice this sentence: ‘I do not believe I have a drug problem’. 32 Possibly, this alludes to low self-esteem. The relationship between self-esteem and substance use has been extensively studied. 33

As a result, many substance use disorder patients may not seek treatment except for other issues, such as family disputes, mood disorders, sleep difficulties or other mental issues. About 76% of men and 65% of women who use drugs or are dependent have at least 1 additional psychiatric diagnoses (including lifetime alcohol use or addiction), 34 and 20% of individuals with severe mental health issues will acquire an SUD. 35 Only 7.4% of these individuals receive treatment for both illnesses, while the remaining 55% do not receive any treatment. Sometimes, the existence of these co-occurring diseases hinders the treatment of SUD. The role of mental diseases co-occurring with SUD is more complex, and the likelihood of receiving assistance depends on the disorder. 36

At the social level, the most significant barriers or facilitators to treatment were characterised as supportive or unsupportive connections with family members, friends and the therapeutic team. The evidence suggests that family support is more important than other types of support. The majority of research indicates that the family has a distinct impact on SUD compared to the rest of a person’s social network. 37 Support is crucial, but familial bonds are as essential. Ineffective parental supervision leads to poor social skills, and as a result, children tend to associate with unhealthy groups and may engage in substance use. 38 Without sufficient social support, these relationships flourish. Lonely people have a tendency to seek out harmful connections, and these dysfunctional friendships encourage relapse. 39 Post-discharge substance consumption by spouses or significant others significantly enhanced relapse risk. 40 The impact of stigma is mitigated when a person has access to support resources. Social support has a positive effect on well-being. Certain functions are dependent on particular social support. Considered crucial for shaping drug use programmes are community support, trust and participation. People’s perceptions of the persons and resources that can assist them can be more accurate predictors of health outcomes than the actual people who can assist. 40

Although low motivation is considered as a significant barrier to SUD treatment at the person level, it is greatly influenced by the social level. Low motivation, denial and resistance are frequently regarded to be typical of individuals with SUD. Due to its dynamic character, motivation is one of the most significant variables in encouraging people to adhere to treatment. The clinician could be one of the sources of building motivation by establishing a therapeutic connection based on mutual respect and the client’s autonomy while simultaneously assuming the position of treatment counsellor or coach. 41 The therapists’ relationship with the treatment team can influence their motivation, which is a double-edged sword. Dependence on the treatment team has unfavourable outcomes, whereas motivated interactions have favourable outcomes. This is especially significant for individuals with poor desire, although the processes underlying this potential ‘match’ between patient and treatment are unknown. 42

We observed the most frequent barriers or facilitators at the structural level. Three overall barriers were identified at this level: treatment provider service issues, legal barriers and policy constraints. Financial concerns, insufficient time, unsecured and unreliable treatment structures, inaccessibility to all treatment seekers, insufficient treatment team training and management style were noted as the most common at this level. Over 80% of respondents in 1 poll agreed with the greater utilisation of research findings and new approaches in SUD treatment. 43 A study comparing Eastern and Western countries revealed that certain types of treatment are linked with greater stigma than conventional approaches. 44 Stigma is typically caused by ignorance, lack of education, lack of genuine conception and other issues. Stigma emerges from various sources, which function synergistically and have a profound impact on the individual’s life. 27

In the consultation process, insufficient knowledge and low self-confidence manifested as obstacles. Practitioners were either unaware of or lacked a proper understanding of the instructions, particularly in regards to the different definitions of alcohol measurements and strengths. There was a lack of equitable access to suitable intervention for some patients with particular features, which affected the likelihood of being sought for treatment. 22 According to some data, the context of intervention delivery could facilitate brief intervention, as patient acceptability is one of the most important factors. We are aware that there is no set of broadly approved SUD treatment guidelines. 10 Beneficial would be a community-based collaborative model that facilitates engagement with appropriate institutions.

In the majority of instances, SUD treatment falls outside of the continuum of care, typically due to logistical issues and inadequate provider understanding. Despite the fact that SUD are medical conditions, treatment for SUD is not standardised, particularly for women. 15 In certain instances, children and even teenagers have been neglected or a large number of patients have been referred for inpatient care. 45 In certain circumstances, however, an outpatient setting may be preferred. 10 Due to their age, many treatment programmes may prescribe OUD medications to younger patients or conversely, the usage of such medications may be a barrier to their admittance into treatment if they are already receiving an OUD prescription provided elsewhere. 9 The gap between what is known about SUD and what is done about them is relevant for both rehabilitation professionals and those who utilise rehabilitation services. 46

Conclusion

According to a study of prior review research, the structural level is the most frequently cited barrier to SUD treatment, as well as the most frequently indicated facilitator. Existing rules, related policies and healthcare systems must be modified, and this modification must be carefully planned. Diverse treatment programmes for all groups, good management, fair rules and supportive policies can enhance the conditions of SUD treatment. We believe it is crucial that the holistic model be used to the SUD intervention programme and that the treatment of SUD should not be the sole responsibility of physicians, families or people. We require a macro-focused system. We should not forget that one of the most significant obstacles to SUD treatment is the independent activity of each major level in isolation from one another.

Limitation

Many grey or non-English review articles that could have been found from other databases were excluded from this study due to the inclusion criteria. On the other hand, not all systematic review research that led to the current study employed the same methodology; some were meta-analyses and others were merely systematic reviews. Some reviews utilised qualitative approach, while others utilised quantitative methodology. Nonetheless, despite this variation, the researchers attempted to draw unified conclusions.

Other limitation was primary articles overlapped the probability across the reviews. We reduce the impact of this limitation by finding overlapping and handling it in the result extraction.

Finally, this overview study extracts barriers and facilitators to SUD treatment, according to various studies. Some of these factors might depend highly on settings, regions and nations. Therefore, readers must be cautious when applying the findings to specific settings.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study was provided by National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) Grant No. 964026. NIMAD had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: Study was designed by Ali Farhoudian, Alireza Noroozi and Mohsen Malekinejad. Search for review articles done by Zahra Hooshyari and Azam Pilevari. Focus group (expert panel) to select review articles included Emran Razaghi, Azarakhsh Mokri, Ali Fahoudian, Alireza Noroozi, Mohsen Malekinejad, Mohammad Reza Mohammadi. Screening for fit review article done by Zahra Hooshyari, Emran Razaghi and Azam Pilevari. Analysis and summating done by Emran Razaghi and Zahra Hooshyari. Zahra Hooshyari write first draft of manuscript and, Emran Razaghi, Alireza Noroozi and Ali Farhoudian promote it. Finally, all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. MSI. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;9:135-142. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Volkow ND. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. DIANE Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mark TL, Levit KR, Vandivort-Warren R, Coffey RM, Buck JA. Trends in spending for substance abuse treatment, 1986-2003. Health Aff. 2007;26:1118-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horgan C, Skwara KC, Strickler G, et al. Substance Abuse: The Nation’s Number One Health Problem. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Schneider Institute for Health Policy; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6. French MT, Popovici I, Tapsell L. The economic costs of substance abuse treatment: updated estimates and cost bands for program assessment and reimbursement. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:462-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. International Guidelines for Estimating the Costs of Substance Abuse. World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S, et al. The costs of substance abuse in Canada 2002. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hadland SE, Bagley SM, Rodean J, et al. Receipt of timely addiction treatment and association of early medication treatment with retention in care among youths with opioid use disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:1029-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blevins CE, Rawat N, Stein MD. Gaps in the substance use disorder treatment referral process: provider perceptions. J Addict Med. 2018;12:273-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S, Toneatto T. Barriers to treatment: why alcohol and drug abusers delay or never seek treatment. Addict Behav. 1993;18:347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cumming C, Troeung L, Young JT, Kelty E, Preen DB. Barriers to accessing methamphetamine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: a systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016;35:22-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelly S, Olanrewaju O, Cowan A, Brayne C, Lafortune L. Alcohol and older people: a systematic review of barriers, facilitators and context of drinking in older people and implications for intervention design. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun AP. Program factors related to women’s substance abuse treatment retention and other outcomes: a review and critique. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnett ER, Knight E, Herman RJ, Amarakaran K, Jankowski MK. Difficult binds: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers to treatment among mothers with substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126:108341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grella CE, Ostile E, Scott CK, Dennis M, Carnavale J. A scoping review of barriers and facilitators to implementation of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder within the criminal justice system. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;81:102768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marshall Z, Dechman MK, Minichiello A, Alcock L, Harris GE. Peering into the literature: a systematic review of the roles of people who inject drugs in harm reduction initiatives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;151:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Werb D, Strathdee SA, Meza E, et al. Institutional stakeholder perceptions of barriers to addiction treatment under Mexico’s drug policy reform. Glob Public Health. 2017;12:519-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lunny C, Pieper D, Thabet P, Kanji S. Managing overlap of primary study results across systematic reviews: practical considerations for authors of overviews of reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:140-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health. 2011;33:412-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sarkar S, Tom A, Mandal P. Barriers and facilitators to substance use disorder treatment in low-and middle-income countries: a qualitative review synthesis. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56:1062-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lagisetty P, Klasa K, Bush C, Heisler M, Chopra V, Bohnert A. Primary care models for treating opioid use disorders: what actually works? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi S, Rosenbloom D, Stein MD, Raifman J, Clark JA. Differential gateways, facilitators, and barriers to substance use disorder treatment for pregnant women and mothers: a scoping systematic review. J Addict Med. 2022;16:e185-e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Notley C, Blyth A, Maskrey V, Craig J, Holland R. The experience of long-term opiate maintenance treatment and reported barriers to recovery: a qualitative systematic review. Eur Addict Res. 2013;19:287-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shrivastava A, Johnston M, Bureau Y. Stigma of mental illness-1: clinical reflections. Mens Sana Monogr. 2012;10:70-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Room R. Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:143-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull (Bp). 1999;25:467-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mansouri L, Dowell DA. Perceptions of stigma among the long-term mentally ill. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1989;13:79-91. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Byrne P. Psychiatric stigma. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:281-284. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Owens MD, Chen JA, Simpson TL, Timko C, Williams EC. Barriers to addiction treatment among formerly incarcerated adults with substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malcolm BP. Evaluating the effects of self-esteem on substance abuse among homeless men. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2004;48:39. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zilberman ML, Tavares H, Blume SB, el-Guebaly N. Substance use disorders: sex differences and psychiatric comorbidities. Can J Psychiatr. 2003;48:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, Seay KD. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;61:47-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blanco C, Iza M, Rodríguez-Fernández JM, Baca-García E, Wang S, Olfson M. Probability and predictors of treatment-seeking for substance use disorders in the US. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:136-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCrady BS, Ladd BO, Hallgren KA. Theoretical bases of family approaches to substance abuse treatment. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lochman JE, van den Steenhoven A. Family-based approaches to substance abuse prevention. J Prim Prev. 2002;23:49-114. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kingree JB, Stephens T, Braithwaite R, Griffin J. Predictors of homelessness among participants in a substance abuse treatment program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69:261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ellis B, Bernichon T, Yu P, Roberts T, Herrell JM. Effect of social support on substance abuse relapse in a residential treatment setting for women. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:213-221. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Legal Issues: Integrating Substance Abuse Treatment and Vocational Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ilgen MA, McKellar J, Moos R, Finney JW. Therapeutic alliance and the relationship between motivation and treatment outcomes in patients with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Forman RF, Bovasso G, Woody G. Staff beliefs about addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang LH, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma and beliefs of efficacy towards traditional Chinese medicine and western psychiatric treatment among Chinese-Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14:10-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weiner DA, Abraham ME, Lyons J. Clinical characteristics of youths with substance use problems and implications for residential treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:793-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Scott CG, Patterson JB. Gaps between addiction treatment and research: challenges for rehabilitation counselors. J Appl Rehabil Couns. 2003;34:3-8. [Google Scholar]