Abstract

Amino acid residues responsible for the large difference in thermostability between HMfB and HFoB, archaeal histones from the hyperthermophile Methanothermus fervidus and the mesophile Methanobacterium formicicum, respectively, have been identified by site-specific mutagenesis. The thermal denaturation of ∼70 archaeal histone variants has been monitored by circular dichroism, and the data generated were fit to a two-state unfolding model (dimer→two random coil monomers) to obtain a standard-state (1M) melting temperature for each variant dimer. The results of single-, double-, and triple-residue substitutions reveal that the much higher stability of rHMfB dimers, relative to rHFoB dimers, is conferred predominantly by improved intermolecular hydrophobic interactions near the center of the histone dimer core and by additional favorable ion pairs on the dimer surface.

Histones from mesophilic, thermophilic, and hyperthermophilic Archaea have similar sequences and folds but very different thermodynamic stabilities (5, 8, 9, 14, 18, 20). These small proteins (66 to 69 amino acid residues) exhibit fully reversible temperature-, salt-, and pH-dependent unfolding and refolding and therefore provide an experimentally tractable system to relate primary sequences, and three-dimensional structures, to inherent protein stability. For example, HMfB and HFoB from the hyperthermophile Methanothermus fervidus (17) and mesophile Methanobacterium formicicum (2), respectively, have amino acid sequences that are 78% identical (Fig. 1a), and the tertiary structures of recombinant (r) (HMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 dimers have a root-mean-square deviation for backbone atoms of only 0.65 ± 0.13 Å2 (18, 20). However, under identical solution conditions, they have maximum free energies of unfolding of 14.6 and 7.2 kcal/mol, respectively, and unfold at temperatures that differ by >30°C (8). To identify the residues responsible for this large difference in structural stability, site-specific mutagenesis, followed by synthesis and purification from Escherichia coli, has been used to obtain rHMfB and rHFoB variants with residue substitutions at all of the sites at which rHMfB and rHFoB differ (Fig. 1a and b). Here we report the thermostability of each variant based on circular dichroism (CD) measurements of thermal unfolding transitions and the interpretation of these data in terms of the difference in stability of the (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 histone folds.

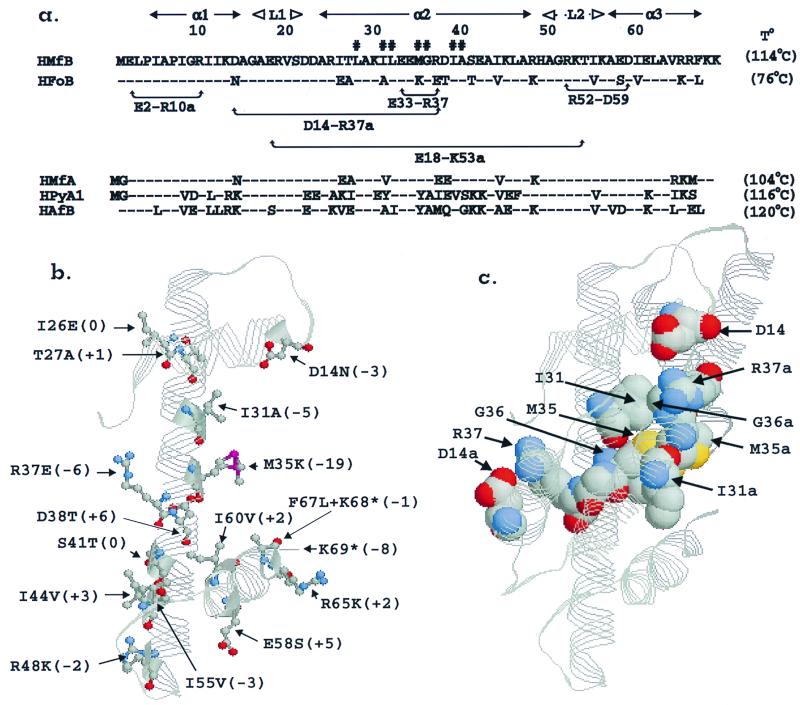

FIG. 1.

Archaeal histone sequences and structures. (a) The amino acid sequence of HMfB from M. fervidus (optimum growth temperature, 83°C) aligned with the sequences of HFoB from M. formicicum (optimum growth temperature, 43°C), HMfA from M. fervidus, HPyA1 from Pyrococcus strain GB-3a (optimum growth temperature, 95°C), and HAfB from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (optimum growth temperature, 85°C) (8, 14). Sites containing the same residue as in HMfB are indicated by hyphens, and differences are indicated by the appropriate single letter amino acid code. The regions that form α1, α2, α3, L1, and L2; residues that interact to form the hydrophobic dimer core (#); and residues that form ion pairs in (rHMfB)2 are identified (Protein Data Bank website [see text]; 18). The T° values established previously for recombinant versions of these four archaeal histones in 0.2 M KCl (pH 4) are listed in parentheses (8, 9). (b) A RasMol-generated (R. Sayle, molecular visualization program, RasMol 2.6 [http://www.umass.edu/microbio/rasmol/distrib/html]) figure of the histone fold of an rHMfB monomer (Protein Data Bank website [see text]), with stick-and-ball representations shown for the residues at the locations at which HMfB and HFoB differ (see panel a). The change in T° (ΔT°; see Table 1) that resulted from the introduction of each rHFoB residue into rHMfB is listed in parentheses following the residue substitution. For example, rHMfB has isoleucine and rHFoB has alanine at position 31, and the T° of the rHMfB (I31A) variant is 5°C lower than that of wt rHMfB. The ΔT° values of <3°C are within the range of experimental error but were included to complete the figure. (c) A RasMol-generated (see above) (rHMfB)2 dimer (Protein Data Bank website [see text]) with the intermonomer hydrophobic residue interactions at the center of the core and two ionic interactions on the dimer surface (D14-R37a; D14a-R37) highlighted by space-filled residue representations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed mutagenesis and recombinant histone purification.

Specific mutations were introduced into hmfB and hfoB by using the Altered Sites I and II (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) and QuikChange (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) kits. The manufacturers' protocols were followed, with mutagenic oligonucleotide primers (sequences available on request) purchased from Ransom Hill Biosciences (Romana, Calif.). Each construction was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and then cloned into pKK223-3 and transformed into E. coli JM105 for rHMfB synthesis (15, 16) or cloned into pRAT4 and transformed into E. coli B834(DE3) for rHFoB synthesis (9, 13). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (400 μM; IPTG) was added to cultures of the E. coli transformants growing at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml to induce variant synthesis (13, 15), and incubation was continued for 3 h at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at 30-min intervals, and the polypeptide content of the E. coli cells was visualized by Coomassie blue staining after cell lysis and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15). Accumulation of an archaeal histone was indicated by an increase in the intensity of a stained band that migrated faster than almost all other polypeptides present. The E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation, and lysed by passage through a French pressure cell, and the variant was then purified from the lysate as previously described for rHMfB and rHFoB (8, 9, 16). The composition and concentration of the archaeal histone preparations were determined by acid hydrolysis and amino acid analysis (8), and DNA binding and archaeal nucleosome formation were documented by agarose gel shift assays (16, 17). In cases where there was no detectable accumulation of an archaeal histone after IPTG addition, the accuracy of the recombinant DNA construction was reconfirmed by sequencing, and additional attempts were made to induce synthesis of the variant, but generally without success.

CD spectropolarimetry.

CD spectra of the recombinant archaeal histone variants were obtained at 25°C using an AVIV 62A-DS spectropolarimeter (Aviv, Lakewood, N.J.) with a 1-mm-path-length cylindrical quartz cell and averaging times of 2 to 5 s. Temperature-induced changes in the CD measurements at 222 nm (θ222) were determined at 1°C intervals from 0 to 99°C using a 10-mm-path-length quartz cell with an averaging time of 5 s. The temperature was maintained to within ±0.2°C with a 1-min equilibrium time between each temperature increment. In terms of histone monomers, the rHMfB and rHFoB variant solutions investigated ranged in concentration from 2.6 to 5.3 μM and from 1.0 to 5.6 μM, respectively. Baseline measurements were determined using deionized water and subtracted from the experimental data. As previously described for both archaeal and eucaryal histones (7, 8), a two-state model in which a histone dimer unfolds directly into two random coil monomers (D→2M) with negligibly populated intermediate states fitted the experimental data and was used to calculate standard state (1M) midpoint unfolding temperatures (T° values).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Thermal unfolding transitions and T° values.

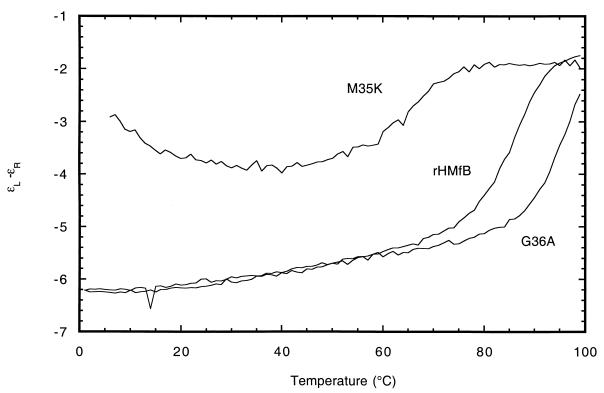

(rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 have secondary structures that are over 70% α-helical, and changes in ellipticity at 222 nm were therefore measured to monitor protein unfolding transitions (6). To observe complete unfolding transitions below 99°C, the highest operating temperature of the CD spectropolarimeter, measurements of (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 and their variants were made in solutions containing 0.2 M and 1 M KCl, respectively (8). The thermal transition mid-point temperatures (Tm) observed for unfolding were dependent on the protein concentration, as expected for dimers, and were extrapolated to 1M standard-state values (T°) for comparative purposes. Examples of the unfolding transitions observed are shown in Fig. 2, and when assayed, reduction of the temperature subsequently resulted in the histone variant refolding. As described in detail previously for wild-type (wt) archaeal histones (8), based on the excellent fit of the two-state model (D→2M) to the data, this model was used to calculate T° values for each variant from the thermal unfolding transition data (Tables 1 and 2).

FIG. 2.

Thermal unfolding transitions of wt rHMfB, rHMfB (M35K), and rHMfB (G36A) monitored by CD at 222 nm. The CD intensities are given as the difference in extinction coefficient for left (ɛL) and right (ɛR) circularly polarized light (liters per centimeter × moles of residues). The results shown illustrate unfolding transitions by variants with increased (G36A) and with decreased (M35K) thermostability relative to that of wt rHMfB and were collected from ∼5 μM protein dissolved in 0.2 M KCl–25 mM glycine buffer (pH 4). The rHMf (M35K) variant data also demonstrate that destabilization resulted in convergence of the low and high temperatures of denaturation and a molecular population that included unfolded molecules at all temperatures.

TABLE 1.

T° values of rHMfB variantsa

| rHMfB variant | Residue location | rHMfB→rHFoBb | ΔT° |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | (114)c | ||

| I31A | α2 | Y | −5 |

| M35K | α2 | Y | −19 |

| G36A | α2 | N | +5 |

| R37E | α2 | Y | −6 |

| D38E | α2 | N | +8 |

| D38T | α2 | Y | +6 |

| H49E | α2 | N | −5 |

| H49K | α2 | N | −5 |

| E58S | α3 | Y | +5 |

| F67A | C termd | N | −5 |

| K69* | C term | Y | −8 |

| D14N + R37E | α1 + α2 | Y | −4 |

| M35K + D38T | α2 + α2 | Y | −16 |

| M35K + F67L | α2 + C term | Y | −11 |

| M35K + F67L + K68* | α2 + C term + C term | Y | −14 |

| M35K + D38T + F67L | α2 + α2 + C term | Y | −11 |

| M35K + D38T + F67L + K68* | α2 + α2 + C term + C term | Y | −30 |

| R37E + D38T | α2 + α2 | Y | −5 |

| D38T + F67L | α2 + C term | Y | +5 |

T° values were calculated as previously described (8) for wt rHMfB in 0.2 M KCl–25 mM glycine buffer (pH 4), with an error estimate of ±3°C. Unfolding transitions were also measured for rHMfB variants with D14N, I26E, T27A, I31V, M35Y, S41T, I44V, R48K, H49A, H49D, I55V, I60V, V64R, R65K, R66M, F67L, I31Y plus M35Y, D38T plus K69*, I44V plus I55V, I44V plus I60V, I55V plus I60V, I44V plus I55V plus I60V, and F67L plus K68* substitutions, but the T° values calculated for these variants differed by <3°C from that of rHMfB and are therefore not listed. The R37E variant did not bind DNA based on negative agarose gel shift assays.

Substitutions that do (Y) or do not (N) replace the rHMfB residue with the corresponding rHFoB residue (see Fig. 1a).

T° value determined for wt (rHMfB)2 dimers (8). The change in this value (ΔT°) is listed for each rHMfB variant.

C term, C terminus.

TABLE 2.

T° values of rHFoB variantsa

| rHFoB variant | Residue location | rHFoB→rHMfBb | ΔT° |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | (92)c | ||

| E26I | α2 | Y | +6 |

| A31I | α2 | Y | +11 |

| A31Y | α2 | N | +12 |

| K35M | α2 | Y | +15 |

| K35Y | α2 | N | +17 |

| K35F | α2 | N | +20 |

| G36A | α2 | N | +8 |

| E37R | α2 | Y | +4 |

| V55I | L2 | Y | −5 |

| S58E | α3 | Y | +4 |

| V60I | α3 | Y | +5 |

| V64R | α3 | N | −8 |

| A31I + K35M | α2 + α2 | Y | +25 |

| A31I + K35Y | α2 + α2 | N | +19 |

| A31I + K35M + V64R | α2 + α2 + α3 | N | +13 |

| K35M + V64R | α2 + α3 | N | +8 |

| K35M + L67F | α2 + α3 | Y | +12 |

| K35M + *68K | α2 + C termd | Y | +6 |

| K35M + *68K + *69K | α2 + C term + C term | Y | +21 |

| E37R + T38D | α2 + α2 | Y | −4 |

T° values were calculated as previously described (8) for wt rHFoB in 1 M KCl–25 mM glycine buffer (pH 4), with an error estimate of ±3°C. Unfolding transitions were also measured for rHFoB variants with N14D, N14K, N14K plus E37R, E37R plus T38D, L67F, *68K, *68K plus *69K, and L67F plus *68K plus *69K substitutions, but the T° values calculated for these variants differed by <3°C from that of wt rHFoB and are therefore not listed.

Substitutions that do (Y) or do not (N) replace the rHFoB residue with the corresponding rHMfB residue (see Fig. 1a).

T° value determined for wt (rHFo)2 dimers (8). The change in this value (ΔT°) is listed for each rHFoB variant.

C term, C terminus.

Fold stabilization by hydrophobic core interactions.

The rHMfB and rHFoB monomers fold into canonical histone folds (1), namely, a long central α-helix (α2) flanked and separated from two shorter α-helices (α1 and α3) by two short β-strand loops (L1 and L2; Fig. 1). Dimer formation is essential for histone fold stabilization (5, 7), and intermolecular interactions between residues positioned along the adjacent buried surfaces of the antiparallel-aligned α2a appear to be primarily responsible for histone dimer formation and maintenance (Fig. 1c) (10, 14). Consistent with α2-α2a interactions (“a” designates a residue or structure in the second monomer of a dimer [18]) contributing predominantly to the difference in (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 stabilities, 9 of the 15 differences in the rHMfB and rHFoB sequences are in α2/α2a (Fig. 1a and b). Two of these, 131 and M35 in rHMfB versus A31 and K35, respectively, in rHFoB, result in different residues participating at the center of the buried α2-α2a interaction (Fig. 1c). In archaeal histone dimers, residues 35 and 35a interact at the center of the α2-α2a interaction (18, 20), and substituting a lysine, as found in rHFoB, for the methionine in rHMfB resulted in an rHMfB (M35K) variant with a 19°C-lower T° (Table 1). The reciprocal substitution in rHFoB generated an rHFoB (K35M) variant with a 15°C-higher T° (Table 2). Substitution of either tyrosine or phenylalanine at position 35 also resulted in rHFoB (K35Y; K35F) variants with much-increased T° values (Table 2), whereas the rHMfB (M35Y) variant had essentially the same T° as that of wt rHMfB. Substituting a larger hydrophobic residue at position 31 also generated rHFoB (A31I; A31Y) variants with increased thermal stabilities, and the rHFoB (A31I plus K35M; A31I plus K35Y) variants with large hydrophobic residues at both positions had even higher thermal stabilities (Table 2). Maintaining hydrophobicity but decreasing the size of the residue at position 31 in rHMfB (I31A) gave a reduced T° (Table 1). A plasmid was constructed to generate the rHMfB (I31A plus M35K) variant, but when the construct was expressed in E. coli, the variant did not accumulate, suggesting that combining A31 and K35 resulted in a protein that folded inadequately and was therefore degraded rapidly in vivo. As several of the archaeal histones from hyperthermophiles have tyrosines naturally at positions 31 and/or 35 (Fig. 1a) (8, 14), an rHMfB (I31Y plus M35Y) variant was constructed with tyrosines at both positions and found to have a T° very similar to that of wt rHMfB.

Glycines 36 and 36a flank the 35-35a interaction at the center of both (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 dimers, and the presence of these small residues results in cavities in both hydrophobic cores (Protein Data Bank [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/cgi/explore.cgi?pid=5348933077468&page=0&pdbId=1A7W]; 18, 20). Larger alanine residues are present at these locations in some of the archaeal histones from hyperthermophiles (Fig. 1a) (8, 14). Both the rHMfB (G36A) and rHFoB (G36A) variants had increased T° values relative to those of wt rHMfB and wt rHFoB, respectively (Tables 1 and 2), consistent with reducing the size of internal cavities adding stability (11, 19). The side chain of residue 67 extends from α3 into the central hydrophobic core, and both rHMfB and rHFoB have a large, hydrophobic residue at this location, phenylalanine and leucine, respectively. The rHFoB (L67F) variant had a stability very similar to that of wt rHFoB, and the reciprocal substitution generated an rHMfB (F67L) variant with marginally increased thermal stability. Combining the F67L substitution with M35K resulted in an rHMfB (M35K plus F67L) variant that was more thermally stable than rHMfB (M35K) but still much less stable than wt rHMfB. As expected, the rHMfB (F67A) variant, with a much smaller residue at position 67, had reduced thermal stability (Table 1).

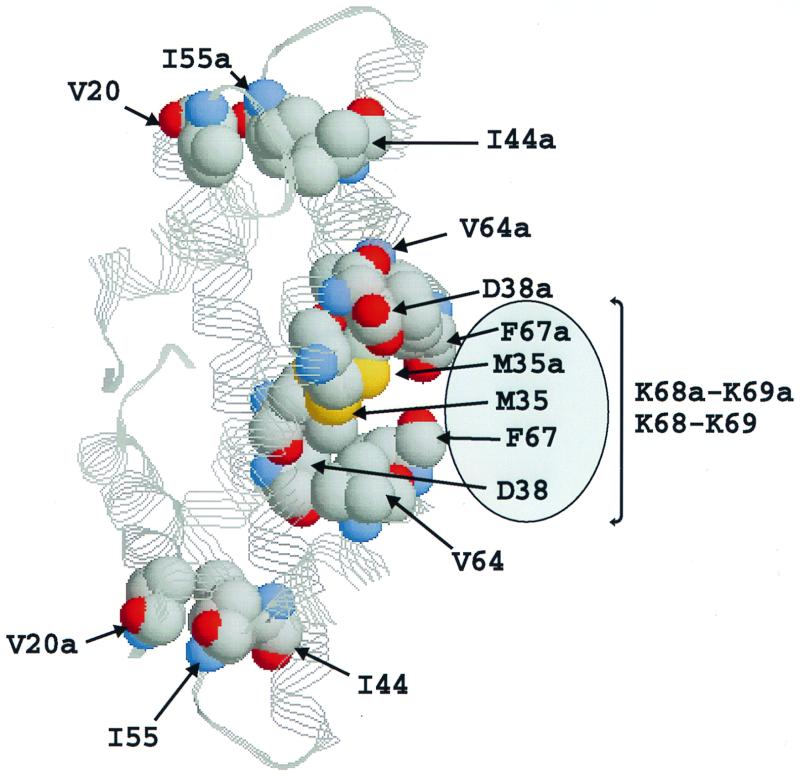

There are three isoleucines in HMfB (I44, I55, and I60) that are replaced by three smaller valines in HFoB, and I44V, I55V, and I60V and all possible combinations of these substitutions were therefore introduced into rHMfB to determine if valine-for-isoleucine substitutions would systematically decrease stability (19). The results obtained, however, show no such consistent trend, and introducing all three substitutions resulted in an rHMfB (I44V plus I55V plus I60V) variant with a T° almost identical to that of wt rHMfB. The side chains of I44/I44a are partially buried by dimer formation and interact with the I55/I55a side chains that are fully buried and tightly packed with the side chains of V20a/V20 by facing inwards from the L1-L2a and L1a-L2 regions (Fig. 3). All archaeal histones except HMfB, including many from hyperthermophiles, have a valine or alanine at position 44, almost all have valine at position 20, and only HMfB and HMfA (also from M. fervidus) have an isoleucine, not a valine, at position 55 (8, 14). It appears likely therefore that smaller valine side chains are more readily accommodated within the space available surrounding positions 20/20a, 44/44a, and 55/55a in an archaeal histone dimer, and consistent with this, the rHMfB (I55V) and rHFoB (V55I) variants had increased and decreased thermal stabilities, respectively. The side chains of isoleucines 60/60a are also partially buried, adjacent to the side chains of leucines 28/28a and alanines 43/43a, forming hydrophobic core interactions between α3/α3a and α2/α2a. Most archaeal histones do have an isoleucine at position 60 (8, 14), and as the rHMfB (I60V) and rHFoB (V60I) variants had slightly reduced and increased thermal stabilities, respectively, having an isoleucine residue at position 60 is preferred for stability.

FIG. 3.

Structure of an (rHMfB)2 dimer (Protein Data Bank website [see text]; 3, 18) generated by RasMol (see legend to Fig. 1) demonstrating the close packing of the side chains of residues V20, I55a, I44a/V20a, I55, and I44 in the dimer core. The region on the surface of the dimer occupied by the four C-terminal residues of rHMfB (K68, K69, K68a, and K69a) is indicated by the oval. These residues are not present in (rHFoB)2 dimers, and as illustrated, they may decrease solvent access to the central region of the (rHMfB)2 dimer core.

Stabilization by ionic interactions.

The histone fold is stabilized by a buried, intramolecular arginine-aspartate interaction in all archaeal (R52-D59 in Fig. 1a) (14) and eucaryal (10) histones, and E2-R10a and E18-K53a intermolecular salt bridges appear similarly to be conserved on the surface of almost all archaeal histone dimers (Fig. 1a). The presence of D14 and R37 in HMfB versus N14 and E37, respectively, in HFoB (Fig. 1a), however, provides (rHMfB)2 dimers with the opportunity to form four additional ion pairs, D14-R27a, D14a-R37, E33-R37, and E33a-R37a, that cannot be formed by (rHFoB)2 dimers (Fig. 1a and c). Preventing this pair formation, by substituting glutamate for arginine at position 37, resulted in an rHMfB (R37E) variant with a 6°C-lower T° (Table 1). The reciprocal substitution generated an rHFoB (E37R) variant with increased thermal stability (Table 2) apparently primarily by replacing the two potentially repulsive E33-E37 interactions along the solvent-exposed surfaces of α2 and α2a with two attractive E33-R37 interactions. rHFoB (N14D; N14K; N14K plus E37R) variants were also constructed with the idea of creating repulsive D14-E37a and N14K-R37a interactions and an attractive K14-E37a interaction, but these variants had thermal stabilities only marginally different from that of wt HFoB. The orientation of α1 relative to α2a is different in (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 dimers (20), and direct residue 14-37a and 14a-37 interactions may therefore be possible only within (rHMfB)2 dimers. Having aspartate and arginine residues at positions 14 and 37, respectively, is unique to HMfB; all other archaeal histones have either a lysine or an asparagine at position 14 and a glutamate (as in HFoB) or a large hydrophobic residue (leucine, isoleucine, or methionine) at position 37 (8, 14).

Stabilization by C-terminal residue protection.

HMfB monomers have two additional C-terminal residues, K68 and K69, that are not present in the shorter HFoB monomers (Fig. 1a). The side chains of K68 and K69 are mobile in solution and have not yet been precisely positioned but have been established as occupying adjacent space on the surface of the dimer consistent with providing the central hydrophobic region with added protection from solvent exposure (Protein Data Bank website [see above]; 18) (Fig. 3). Removal of K69 resulted in an rHMfB (K69*) variant with an 8°C-lower T°, and the reciprocal addition of a lysine generated an rHFoB (*68K) variant with a higher T°. Adding a second lysine (rHFoB [*68K plus *69K]) did not further increase thermal stability, and removing both lysines from rHMfB resulted in an rHMfB (K68*) variant that did not accumulate when synthesized in E. coli. Adding the F67L substitution, to create an rHMfB (F67L plus K68*) variant that lacked both C-terminal lysines but now had a C-terminal leucine, as in HFoB (Fig. 1c), resulted in a variant that did accumulate in E. coli and had thermal stability parameters close to those of wt HMfB. The rHMfB (M35K plus F67L plus K68*) variant also accumulated in E. coli and had slightly reduced thermal stability relative to HMfB (M35K plus F67L).

The presence of K68, K68a, K69, and K69a provides residues 38/38a and 64/64a with more protection from solvent exposure in (rHMfB)2 dimers than in (rHFoB)2 dimers (Fig. 3). Most archaeal histones have a glutamate at position 38 (8, 14); however, rHMfB uniquely has an aspartate-38, and rHFoB has a rare threonine-38, and introducing either a conservative D38E substitution or an rHFoB-like D38T substitution resulted in rHMfB (D38E; D38T) variants with increased T° values. The reciprocal rHFoB (T38D) variant did not accumulate in E. coli, apparently because of unfavorable ionic interactions, as the addition of E37R to create the adjacent sequence R37-D38 that occurs in rHMfB (Fig. 1a) resulted in an rHFoB (R37E plus T38D) variant that did accumulate in E. coli and had thermal stability parameters similar to those of wt rHFoB. Combining the D38T substitution in rHMfB with M35K and F67L generated rHMfB (M35K plus D38T) and (M35K plus D38T plus F67L) variants with T° values intermediate between those of rHMfB (M35K) and wt rHMfB, but when the terminal lysine residues were also removed, the resulting rHMfB (M35K plus D38T plus F67L plus K68*) variant had a 30°C-lower T° (Table 1).

A valine occupies position 64 in both HMfB and HFoB, and a hydrophobic residue is present at this location in all archaeal histones, except rHMfA, which has an arginine at position 64 (Fig. 1a). (rHMfA)2 and (rHMfB)2 have very similar structures (3; Protein Data Bank website [see above]), but (rHMfA)2 dimers unfold at temperatures ∼10°C lower than (rHMfB)2 (8, 9), and replacing the arginine at position 64 with valine resulted in an rHMfA (R64V) variant with an ∼10°C-higher T° (results not shown). Introducing a reciprocal V64R substitution into rHMfB did not result in decreased thermal stability, although the T° of the rHFoB (V64R) variant was 8°C lower than that of rHFoB (Table 2). Combining V64R with M35K resulted in an rHMfB (V64R plus M35K) variant that did not accumulate in E. coli, possibly due to repulsive K35-R64 and K35a-R64a interactions, although such interactions would also be predicted to occur in the core of the rHFoB (V64R) variant.

Conclusions.

Based on the ∼30 archaeal histone sequences so far established (8, 14), conserved residues can be identified that are presumably essential for histone fold formation and/or DNA binding (10, 14), and predictions can be made for residues that might confer differences in thermostability and salt and pH dependence. Here we have investigated the basis for differences in thermostability by measuring the effects of residue substitutions on temperature-induced unfolding by focusing on two archaeal histones with very different stabilities but similar structures (Protein Data Bank website [see above]; 8, 18, 20). The increased stability of proteins from thermophiles compared with that of proteins from mesophiles is frequently attributed to improved hydrophobic core packing (11, 19) and/or an increased number of attractive ionic interactions (4, 12), and the results reported here are consistent with differences in intermonomer hydrophobic core interactions dominating in determining the difference in the (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 fold stabilities. Introducing large hydrophobic residues and decreasing cavity sizes within the cores increased thermostability, combinations of such substitutions had additive effects, and introducing smaller or potentially polar residues decreased stability. Most substitutions that added or removed a potentially attractive or repulsive ionic interaction also had the predicted positive or negative effect on thermostability, but this was not always the case, underlining the limitations of predicting stability even for such very simple proteins. Approximately 70 variants have so far been constructed, with one to four substitutions, and assayed for thermostability, and residue differences that together account for most of the difference in the stabilities of (rHFoB)2 and (rHMfB)2 have been identified. Some results, for example, the increased thermostability of the rHMfB (D38E) variant, however, remain inexplicable, and it has been assumed that the lack of accumulation in E. coli identifies a variant that is so misfolded that it is rapidly degraded when synthesized in E. coli, but this has not been systematically proven. The rHFoB and rHMfB sequences differ at 15 locations (Fig. 1a), and constructing and assaying the thermodynamic stabilities of all possible rHMfB variants with all combinations of rHFoB residues, and/or vice versa, would be a monumental task. As some substitutions would probably also change the overall fold, this would then also be a misguided undertaking if all arguments were based on only the wt (rHMfB)2 and (rHFoB)2 structures. With this in mind, the structures of selected archaeal histone variants must now be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Sandman for construction, purification, and DNA binding assays of several of the archaeal histone variants used in this study.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM53185).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arents G, Moudrianakis E N. The histone fold: a ubiquitous architectural motif utilized in DNA compaction and protein dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11170–11174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darcy T J, Sandman K, Reeve J N. Methanobacterium formicicum, a mesophilic methanogen, contains three HFo histones. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:858–860. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.858-860.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decanniere K, Sandman K, Reeve J N, Heinemann U. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray characterization of the Methanothermus fervidus histones HMfA and HMfB. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1996;24:269–271. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199602)24:2<269::AID-PROT16>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elcock A H. The stability of salt bridges at high temperatures: implications for hyperthermophilic proteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:489–502. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grayling R A, Becktel W J, Reeve J N. Structure and stability of histone HMf from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanothermus fervidus. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8441–8448. doi: 10.1021/bi00026a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirst J D, Brooks C L., III Helicity, circular dichroism and molecular dynamics of proteins. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:173–178. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karantza V, Baxevanis A D, Freire E, Moudrianakis E N. Thermodynamic studies of the core histones: ionic strength and pH dependencies of H2A-H2B dimer stability. Biochemistry. 1995;35:5988–5996. doi: 10.1021/bi00017a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W-T, Grayling R A, Sandman K, Edmondson S, Shriver J W, Reeve J N. Thermodynamic stability of archaeal histones. Biochemistry. 1998;30:10563–10572. doi: 10.1021/bi973006i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, W.-T., K. Sandman, S. L. Pereira, and J. N. Reeve. MJ1647, an open reading frame in the genome of the hyperthermophile Methanococcus jannaschii, encodes a very thermostable archaeal histone with a C-terminal extension. Extremophiles, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Luger K, Mäder A W, Richmond R K, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pace C N. Contribution of the hydrophobic effect to globular protein stability. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:29–35. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90121-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappenberger G, Schurig H, Jaenicke R. Disruption of an ionic network leads to accelerated thermal denaturation of D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:676–683. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peränen J, Rikkonen M, Hyvönen M, Kääriäinen L. T7 vector with a modified T7lac promoter for expression of proteins in E. coli. Anal Biochem. 1996;236:371–373. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeve J N, Sandman K, Daniels C J. Archaeal histones, nucleosomes and transcription initiation. Cell. 1997;87:999–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 6.46–6.48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandman K, Grayling R A, Reeve J N. Improved N-terminal processing of recombinant proteins synthesized in Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:504–506. doi: 10.1038/nbt0595-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandman K, Krzycki J A, Dobrinski B, Lurz R, Reeve J N. HMf, a DNA-binding protein isolated from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanothermus fervidus, is most closely related to histones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5788–5791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starich M R, Sandman K, Reeve J N, Summers M F. NMR structure of HMfB from the hyperthermophile, Methanothermus fervidus, confirms that this archaeal protein is a histone. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:187–203. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takano K, Yamagata Y, Yutani K. A general rule for the relationship between hydrophobic effects and conformational stability of a protein: stability and structure of a series of hydrophobic mutants of human lysozyme. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:749–761. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu W, Sandman K, Lee G E, Reeve J N, Summers M F. NMR structure and comparison of the archaeal histone HFoB from the mesophile Methanobacterium formicicum with HMfB from the hyperthermophile Methanothermus fervidus. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10573–10580. doi: 10.1021/bi973007a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]