Abstract

The Tol-Pal system of Escherichia coli is involved in maintaining outer membrane stability. Mutations in tolQ, tolR, tolA, tolB, or pal genes result in sensitivity to bile salts and the leakage of periplasmic proteins. Moreover, some of the tol genes are necessary for the entry of group A colicins and the DNA of filamentous bacteriophages. TolQ, TolR, and TolA are located in the cytoplasmic membrane where they interact with each other via their transmembrane domains. TolB and Pal form a periplasmic complex near the outer membrane. We used suppressor genetics to identify the regions important for the interaction between TolB and Pal. Intragenic suppressor mutations were characterized in a domain of Pal that was shown to be involved in interactions with TolB and peptidoglycan. Extragenic suppressor mutations were located in tolB gene. The C-terminal region of TolB predicted to adopt a β-propeller structure was shown to be responsible for the interaction of the protein with Pal. Unexpectedly, none of the suppressor mutations was able to restore a correct association between Pal and peptidoglycan, suggesting that interactions between Pal and other components such as TolB may also be important for outer membrane stability.

The cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria, like Escherichia coli, acts as a barrier to the entry of macromolecules into the cell, thus providing a protection against the deleterious action of bacteriocins and digestive enzymes. The envelope is composed of an outer membrane and a cytoplasmic membrane, delimiting the periplasmic space which contains the peptidoglycan. As a consequence, the uptake of macromolecules essential for cell growth requires specific transport systems. For example, the Ton system, composed of TonB and its auxiliary proteins ExbB and ExbD, is necessary for the transport of vitamin B12 and iron-siderophore complexes (6). Group B colicins and bacteriophages T1 and Φ80 have parasitized this system to enter the bacterium (20). Similarly, the infection by filamentous bacteriophages and the sensitivity to the group A colicins require some proteins of the Tol system (12, 15, 26).

Tol proteins are located in the cell envelope and are thought to be involved in the integration of some outer membrane components, such as porins or lipopolysaccharides (9, 21). The tol-pal genes map at 17 min on the E. coli chromosome (26). They are transcribed from two adjacent operons (25). The first operon enables the transcription of the orf1, tolQ, tolR, and tolA genes, whereas the second one comprises tolB, pal, and orf2. orf1 is an open reading frame encoding a cytoplasmic protein of unknown function (23), and orf2 encodes a periplasmic protein whose inactivation induces no obvious alteration in phenotype (25). Mutations in the tol-pal genes cause the disruption of outer membrane integrity, which is evidenced by several phenotypes, including the release of periplasmic content, sensitivity to bile salts, and formation of outer membrane blebs at the cell surface (2, 17, 24). Interactions between some of the proteins of the Tol-Pal system have been characterized. TolQ, TolR, and TolA interact in the cytoplasmic membrane via their transmembrane domains (8, 10, 18). The periplasmic protein TolB was shown to interact with the outer membrane, peptidoglycan-associated proteins OmpA, Lpp, and Pal (4, 7). Thus, TolB and Pal could be part of a multicomponent system linking the outer membrane to peptidoglycan.

The aim of this study was to determine the regions of TolB involved in the interaction of the protein with Pal. To this end, we used suppressor genetic techniques which had previously allowed us to characterize the regions of interaction between TolQ, TolR, and TolA (10, 18). pal point mutations were identified, and some of them involved residues important for interaction with TolB (7). These mutations induce sensitivity to sodium cholate and release of periplasmic proteins in the medium. We used these pal mutants to search for suppressors in tolB.

Mutagenesis and search for suppressors of pal mutations.

Strain JC7752 used in this study was an E. coli K-12 Δ(tolB pal) derivative of 1292 (supE hsdS met gal lacY fhuA, provided by W. Wood). First, an in vivo mutagenesis was performed on a mixture of cells transformed by plasmid pJC417 derivatives (25) containing the tolB-pal-orf2 region and carrying each of the pal mutations. Cells were grown to exponential-growth phase and were washed in citrate buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5). They were then incubated 10 or 20 min at 37°C in the citrate buffer containing 0.4 mg of nitrosoguanidine per ml, were washed with potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7), and were shaken at 37°C for 2 h. After overnight growth in Luria-Bertani medium containing ampicillin, plasmids were extracted according to the method of Birnboim and Doly (3). Strain JC7752 was transformed by the mutagenized plasmids, and cells able to grow on plates containing 2.5% sodium cholate were selected. Plasmids were again extracted from these strains and were reintroduced into JC7752, in order to ascertain that the phenotype observed was really due to the mutagenized plasmids. The region containing the suppressor mutation was localized by subcloning techniques and was entirely sequenced. By using this method of screening, two extragenic suppressor mutations were identified with the pal A88V mutant. This mutant was previously described as having an unexpected phenotype of tolerance towards colicin A (7), like three other mutants (pal P94L, pal S126F, and pal G128D). Since, unlike TolB, Pal had never been reported to be necessary for the translocation of colicin A, the phenotype observed in these four pal mutants could be due to a defect in TolB-Pal interaction. That is why these four mutants seemed to be good candidates for the search of extragenic suppressor mutants. Therefore, we performed a second mutagenesis on each of these four mutants, following the same protocol as described above. Only the mutagenesis of the plasmid carrying the pal A88V mutation led to the characterization of suppressor mutations.

Isolation of intragenic suppressor mutations of pal A88V.

Mutations pal S99F and pal E102K were both isolated as intragenic suppressor mutations of pal A88V. The pal E102K mutations was previously described as a pal-defective mutant (7). Both pal S99F and pal E102K mutations enabled the pal A88V mutant to grow in the presence of sodium cholate and lowered its excretion of periplasmic enzymes, mutant pal E102K being more efficient than mutant pal S99F as a suppressor mutation (Table 1). Thus, the conformation of the region from residues 88 to 102 appeared to be important for Pal function. The region from residues 89 to 130 was shown to be able to bind to TolB and peptidoglycan (5). Residues 97 to 114 constitute an α-helical domain which is well conserved in all OmpA-related proteins and has been proposed to be involved in the association of these proteins with peptidoglycan (14). The suppression observed could, therefore, be explained by a conformation of Pal restoring an interaction with TolB or peptidoglycan. These two hypotheses were tested.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of intragenic suppressor mutants in pala

| pal mutation | Release of ribonuclease Ib | Growth on sodium cholatec | Sensitivity to colicin Ad | Sensitivity to colicin E2d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | − | + | 104 | 105 |

| A88V | + | − | 103 | 104 |

| A88V, S99F | +/− | +/− | 104 | 105 |

| A88V, E102K | − | + | 105 | 106 |

Plasmids pJC417 carrying the indicated pal mutations were introduced into strain JC7752.

Strong (+), intermediate (+/−), or no (−) release of ribonuclease I. The detection of the release of ribonuclease I has been described previously (16).

Growth (+), partial growth (+/−), or absence of growth (−) on plates containing 2.5% sodium cholate.

Lowest dilution of a standard colicin solution that enables strains to grow. Values are shown in arbitrary units.

Total membranes from each mutant were isolated and were then solubilized by 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate to isolate peptidoglycan-associated proteins as described (7). In such conditions, equal amounts of Pal were recovered in the total membrane fraction of parental or mutant strains (data not shown). In pal A88V mutant and the intragenic suppressors, Pal was not associated with peptidoglycan, unlike in the wild-type strain. Therefore, the suppression could not be due to the restoration of an interaction with peptidoglycan.

Mutant pal A88V is 10-fold more tolerant towards colicins A and E2 than is the wild-type strain (Table 1); this phenotype is reproducibly suppressed in both pal double mutants. Since, unlike TolB, Pal is not involved in the entry of colicins A and E2, these suppressor phenotypes may reveal a change in the conformation of TolB, via a modification of the TolB-Pal interaction. In mutant pal A88V, the TolB-Pal complex could still be evidenced by chemical cross-linking, which was not the case for the pal E102K mutant (7). We wondered if a TolB-Pal complex could be detected in a pal A88V/E102K double mutant. Cross-linking experiments were done on both intragenic suppressor mutants, as described previously (4). An interaction between TolB and Pal could be evidenced in both intragenic suppressor mutants (data not shown). Thus, intragenic suppressor mutations appeared to lead to a conformation of Pal able to functionally interact with TolB. When combined with other pal mutations leading to the same colicin-tolerant phenotype as the pal A88V mutation, the pal E102K mutation never restored a wild-type phenotype. Thus, the suppression of the pal A88V mutation by the pal E102K mutation was allele specific.

Isolation of extragenic suppressor mutations of pal A88V in tolB.

Twelve mutations affecting 11 different residues of tolB were isolated as suppressor mutations of pal A88V (Table 2). They enabled the pal A88V mutant to grow on plates containing sodium cholate and lowered its excretion of periplasmic enzymes, some mutants being more efficient than others in suppressing the pal A88V phenotype. In most cases, the tolB mutations could not suppress the phenotypes of tolerance to colicins A and E2 of mutant pal A88V. Three tolB point mutations (H246Y, A249V, and T292I) affected the activity of TolB, whereas the others had phenotypes similar to the wild type. All the suppressor mutations were subcloned into plasmid pJC417 derivatives carrying mutations pal P94L, pal S126F, or pal G128D, in order to test their allele specificity. In all cases, the tolB mutation was strictly specific of pal A88V, because it only suppressed pal A88V sensitivity to sodium cholate and leakage of periplasmic enzymes (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Suppression of pal A88V mutation by tolB mutationsa

| pal mutation | tolB mutation | Release of ribonuclease Ib | Growth on sodium cholatec | Sensitivity to colicin Ad | Sensitivity to colicin E2d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Wild type | − | + | 104 | 105 |

| V218M | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| H246Y | +/− | − | 104 | 105 | |

| A249V | − | − | 104 | 105 | |

| P250S | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| P250L | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| G267D | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| T292I | +/− | + | 1 | 1 | |

| E293G | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| T306I | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| D308N | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| P313L | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| T380M | − | + | 104 | 106 | |

| A88V | Wild type | + | − | 103 | 104 |

| V218M | +/− | + | 103 | 103 | |

| H246Y | − | + | 103 | 104 | |

| A249V | − | + | 104 | 105 | |

| P250S | +/− | + | 103 | 103 | |

| P250L | +/− | + | 103 | 104 | |

| G267D | + | +/− | 103 | 104 | |

| T292I | +/− | + | 1 | 1 | |

| E293G | − | + | 104 | 104 | |

| T306I | − | + | 104 | 104 | |

| D308N | +/− | + | 103 | 104 | |

| P313L | +/− | + | 103 | 104 | |

| T380M | + | + | 104 | 106 |

Plasmids pJC417 carrying the indicated tolB and pal mutations were introduced into strain JC7752.

Strong (+), intermediate (+/−), or no (−) release of ribonuclease I. The detection of the release of ribonuclease I has been described previously (16).

Growth (+), partial growth (+/−), or absence of growth (−) on plates containing 2.5% sodium cholate.

Lowest dilution of a standard colicin solution that enables strains to grow. Values are shown in arbitrary units.

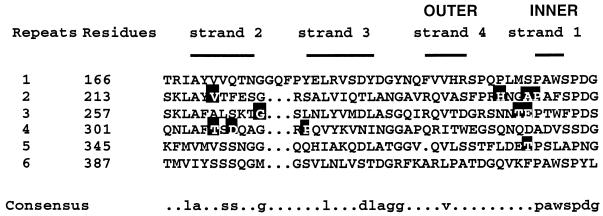

All the extragenic suppressor mutations of pal A88V are located in the C-terminal region of TolB. This suggests that this region of TolB is important for its interaction with Pal. We already knew that TolB and Pal could be associated in pal A88V mutant (7). Cross-linking experiments were performed in order to verify that TolB and Pal could also form complexes in suppressor mutants. This was the case in all strains (data not shown). Therefore, the suppressor phenotype may not be explained by the restoration of a TolB-Pal complex, but rather by a change in the way in which these two proteins interact. Interestingly, the C-terminal region of TolB was proposed to adopt a β-propeller structure (19). Similar organizations were identified in several eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteins, such as the large family of proteins containing WD repeats (22) or the methanol dehydrogenase from Methylophilus methylotrophus (27), as well as the serine-threonine protein kinase of Thermonospora curvata (13). However, the function of β-propeller structures remains unknown. The C-terminal domain of E. coli TolB was shown to be composed of six repeats organized around a central axis, such that they could be likened to the blades of a propeller (19). Each repeat contains four regions predicted to be antiparallel β-strands, strand 4 being outside and strand 1 being inside (Fig. 1). The suppressor mutations of pal A88V isolated in tolB are located in repeats 2 to 5 and are clustered between β-strands 2 and 3 and 4 to 1 (Fig. 1). In a three-dimensional representation, these residues are somewhat inside the β-propeller. The C-terminal domain of TolB could form a cavity into which a part of Pal could enter. The three mutants affecting TolB activity are located between β-strands 4 and 1, probably in a loop near the central axis, just before or at the beginning of the inner strand. Therefore, this particular region may also play a role in TolB activity.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of repeats found in the C-terminal domain of E. coli TolB. The positions of residues involved in suppressor mutations of pal A88V are shaded in black. The four β-strands are indicated above the alignment, as shown by Ponting and Pallen (19). The consensus sequence was defined by specific amino acids appearing more than three times at the same position.

Here again, we checked the ability of the tolB suppressors to restore the association of Pal with peptidoglycan. Equal amounts of Pal were present in total-membrane fractions of the parental and mutant strains (data not shown). None of the mutants could compensate for the lack of association between Pal (A88V) and peptidoglycan. In E. coli, other noncovalently peptidoglycan-associated outer membrane proteins include porins and OmpA. Mutations in the structural genes encoding such proteins do not lead to a phenotype of defect in outer membrane stability in this bacterium, indicating that the association between these proteins and peptidoglycan may more reflect an affinity between these components than an interaction involved in maintaining outer membrane stability. However, this is not the case for other OmpA-related proteins such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa OprF protein which has been shown to be involved in the maintenance of outer membrane integrity (11).

Concluding remarks.

We have characterized the domains important for the interaction between Pal and TolB and shown that the association between Pal and peptidoglycan is not as important as previously thought for outer membrane stability. The determination of the tertiary structure of TolB (1) and Pal will be necessary to identify the exact parts of both proteins which interact with each other. It has been recently reported that, in vitro, the TolB-Pal complex was not associated with the peptidoglycan, leading to the conclusion that Pal may exist under two forms, one bound to TolB and another bound to peptidoglycan (5), but we still wonder what the real physiological significance of the Pal-peptidoglycan association could be. The pal mutants that we isolated may be impaired in their affinity with TolB, peptidoglycan, or both. In addition, the existence of additional unknown factors which can also influence the outer membrane stability cannot be excluded. More-accurate techniques than those used in this study to characterize the interaction between Pal, TolB, and peptidoglycan will be necessary to determine the exact relationships between these three components leading to the maintenance of outer membrane integrity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the CNRS (Département des Sciences de la Vie) and MESR. P.G. was a recipient of an AMN fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abergel C, Rigal A, Chenivesse S, Lazdunski C, Claverie J M, Bouveret E, Bénédetti H. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic study of a component of the Escherichia coli tol system: TolB. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:102–104. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997008020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernadac A, Gavioli M, Lazzaroni J C, Raina S, Lloubès R. Escherichia coli tol-pal mutants form outer membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4872–4878. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4872-4878.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouveret E, Derouiche R, Rigal A, Lloubès R, Lazdunski C, Bénédetti H. Peptidoglycan associated lipoprotein (Pal)-TolB interaction; a possible key for explaining the formation of contact sites between the inner and outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11071–11077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouveret E, Bénédetti H, Rigal A, Loret E, Lazdunski C. In vitro characterization of the peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (PAL)-peptidoglycan and PAL-TolB interactions. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6306–6311. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6306-6311.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun V, Günter K, Hantke K. Transport of iron across the outer membrane. Biol Metals. 1991;4:14–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01135552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavel T, Germon P, Vianney A, Portalier R, Lazzaroni J C. TolB protein of Escherichia coli K-12 interacts with the outer membrane peptidoglycan-associated proteins Pal, Lpp and OmpA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:359–367. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derouiche R, Bénédetti H, Lazzaroni J C, Lazdunski C, Lloubès R. Protein complex within Escherichia coli inner membrane: TolA N-terminal domain interacts with TolQ and TolR proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11078–11084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derouiche R, Gavioli M, Bénédetti H, Prilipof A, Lazdunski C, Lloubès R. TolA central domain interacts with Escherichia coli porins. EMBO J. 1996;15:6408–6415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germon P, Clavel T, Vianney A, Portalier R, Lazzaroni J C. Mutational analysis of the Escherichia coli K-12 TolA N-terminal region and characterization of its TolQ-interacting domain by genetic suppression. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6433–6439. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6433-6439.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh N, Wakebe H, Yoshihara E, Nakae T, Nishino T. Role of protein F in maintaining structural integrity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:983–990. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.983-990.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James R, Kleanthous C, Moore G R. The biology of E colicins: paradigms and paradoxes. Microbiology. 1996;142:1569–1580. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janda L, Tichy P, Spizek J, Petricek M. A deduced Thermonospora curvata protein containing serine/threonine protein kinase and WD-repeat domains. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1487–1489. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1487-1489.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koebnik R. Proposal for a peptidoglycan-associating alpha-helical motif in the C-terminal regions of some bacterial cell-surface proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1269–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazdunski C J, Bouveret E, Rigal A, Journet L, Lloubès R, Bénédetti H. Colicin import into Escherichia coli cells. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4993–5002. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.4993-5002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R C. Isolation and preliminary characterization of periplasmic-leaky mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1979;5:411–416. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90176-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R C. The excC gene of Escherichia coli K-12 required for cell envelope integrity encodes the peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (PAL) Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:735–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazzaroni J C, Vianney A, Popot J L, Bénédetti H, Samatey F, Lazdunski C, Portalier R, Géli V. Transmembrane α-helix interactions are required for the functional assembly of the Escherichia coli Tol complex. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:1–7. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponting C P, Pallen M J. A β-propeller domain within TolB. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:739–740. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postle K. TonB and the Gram-negative dilemma. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2019–2026. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rigal A, Bouveret E, Lloubès R, Lazdunski C, Bénédetti H. The TolB protein interacts with the porins of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7274–7279. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7274-7279.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith T F, Gaitatzes C, Saxena K, Neer E J. The WD repeat: a common architecture for diverse functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun T P, Webster R E. Nucleotide sequence of a gene cluster involved in entry of E colicins and single strand DNA of infecting filamentous bacteriophages into Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2667–2674. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2667-2674.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vianney A, Lewin T M, Bayer W E, Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R, Webster R E. Membrane topology and mutational analysis of the TolQ protein of Escherichia coli required for the uptake of macromolecules and cell envelope integrity. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:822–829. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.822-829.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vianney A, Muller M, Clavel T, Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R, Webster R E. Characterization of the tol-pal region of Escherichia coli: translational control of tolR expression by TolQ and identification of a new open reading frame downstream pal encoding a periplasmic protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4031–4038. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4031-4038.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webster R E. The tol gene products and the import of macromolecules into Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1005–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia Z X, Dai W W, Zhang Y F, White S A, Boyd G D, Scott Mathews F S. Determination of the gene sequence and the three-dimensional structure at 2.4 A resolution of methanol dehydrogenase from Methylophilus W3A1. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:480–501. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]