Abstract

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of PmeI digests of the Nitrosomonas sp. strain ENI-11 chromosome produced four bands ranging from 1,200 to 480 kb in size. Southern hybridizations suggested that a 487-kb PmeI fragment contained two copies of the amoCAB genes, coding for ammonia monooxygenase (designated amoCAB1 and amoCAB2), and three copies of the hao gene, coding for hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (hao1, hao2, and hao3). In this DNA fragment, amoCAB1 and amoCAB2 were about 390 kb apart, while hao1, hao2, and hao3 were separated by at least about 100 kb from each other. Interestingly, hao1 and hao2 were located relatively close to amoCAB1 and amoCAB2, respectively. DNA sequence analysis revealed that hao1 and hao2 shared 160 identical nucleotides immediately upstream of each translation initiation codon. However, hao3 showed only 30% nucleotide identity in the 160-bp corresponding region.

The ammonia-oxidizing autotrophic bacteria derive their carbon for growth from CO2 and their energy for metabolism by the oxidation of ammonia (NH3) to nitrite (NO2−) in the process of nitrification (3, 12, 17). In Nitrosomonas europaea, ammonia is initially oxidized to hydroxylamine by the integral membrane enzyme ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) (7, 8, 11), and the subsequent oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite is catalyzed by the multiheme hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) (2, 5, 15). One unusual genetic feature of N. europaea is that at least five of the nitrification genes are present in more than one copy in the genome. For example, the genes encoding AMO (amoC, amoA, and amoB) are adjacent to each other and are present in two copies (1, 6, 8). The genes encoding HAO (hao) and the genes encoding cytochrome c-554 (cycA), which are in proximity to the HAO genes, are found in three copies (2, 10). However, the locations of these multicopy genes in the genome of N. europaea have not yet been determined. In the present study, we determined the locations of two copies of the AMO-encoding genes (designated amoCAB1 and amoCAB2) and three copies of the HAO-encoding gene (hao1, hao2, and hao3) in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. strain ENI-11, which was isolated from an activated sludge system designed for nitrogen removal.

PFGE and probe characterization.

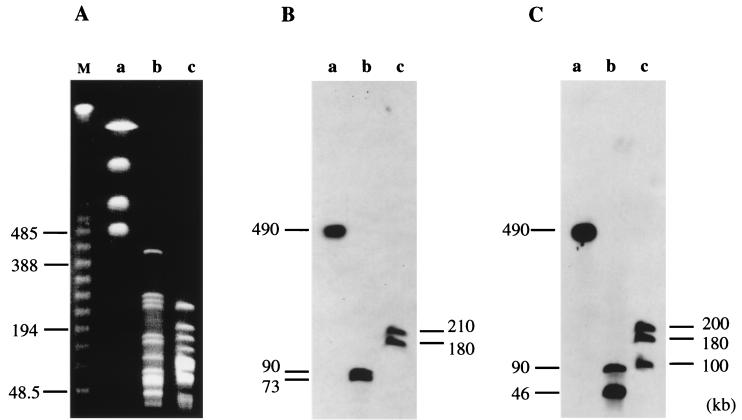

Nitrosomonas sp. strain ENI-11, which was obtained from the Process and Production Technology Center, Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ehime, Japan, was grown aerobically at 28°C in modified Alexander medium (18). The genomic DNA from strain ENI-11 was digested with the rare-cutting endonucleases PmeI, XbaI, and AscI and subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (Fig. 1A). PFGE was performed in the contour-clamped homogeneous electric field mode with the Chromosome DNA Electrophoresis System (Biocraft, Tokyo, Japan) (4, 13, 16). The PmeI fragments of the ENI-11 genome were separated in a 1% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (14) at 5 V/cm with pulses of 60 to 120 s for 45.5 h. The AscI and XbaI digests were separated in 1% agarose at 6 V/cm with pulses of 15 s for 20 h. For DNA fragments in the size range up to 600 kb, the concatemers of lambda DNA (FMC) were used as molecular size standards. For fragments ranging from 600 kb to 2 Mb, chromosomes isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (FMC) were used as molecular size markers. PFGE of the PmeI digests of the ENI-11 chromosome produced four bands ranging from 1,200 to 480 kb. PFGE of the XbaI and AscI digests of the ENI-11 genomic DNA produced at least 31 and 22 fragments ranging from 430 to 10 kb, respectively. Obviously, the DNA bands formed by either XbaI or AscI digests contained unresolved bands under the PFGE conditions used in these experiments.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of PmeI, XbaI, and AscI digests of Nitrosomonas sp. strain ENI-11 genomic DNA (A) and Southern hybridization analysis of the digested genomic DNA with the amoB (B) and hao (C) probes. Lanes: a, PmeI digestion; b, XbaI digestion; c, AscI digestion. The size markers (lane M in panel A) are the concatemers of lambda DNA (FMC).

Southern hybridizations to the ENI-11 genomic DNA digested with PmeI, XbaI, and AscI were performed with the amoB and hao probes (Fig. 1B and C). The amoB probe was amplified by PCR with primers A3 (5′-TATGTACTGCAGGCAGAAGTTGCGCTTG) and A4 (5′-CGAATTCGACAGGCTAATTGATGCTTCG) from the ENI-11 genome. PCR was performed with respective sets of oligonucleotide primers and a Takara Z Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Shiga, Japan) on a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer). The 2.3-kb PCR product was digested with BamHI and SphI, and the resulting 0.3-kb fragment was labeled by a nonisotopic method (fluorescein DNA labeling and detection kit; Amersham). Similarly, the hao probe was prepared from a 2.2-kb PCR product which was amplified with primers H3 (5′-CTCTAGAAATATGGCAAATACGGCACAAGC) and H4 (5′-CTCTAGATAACGATACGGCGCTGTGTC) from the ENI-11 genome. The amoB probe hybridized to only a single fragment, designated PmD, in the PmeI digests and to two fragments in the XbaI and AscI digests. The hao probe also hybridized to the PmD fragment in the PmeI digests, while it hybridized to two and three fragments in the XbaI and AscI digests, respectively. These results suggest that the genes coding for AMO and HAO are present in at least two and three copies in the ENI-11 genome, respectively, as also seen in N. europaea (11, 15). More importantly, the PmD fragment, which is 487 kb in size, contains all of the multiple copies of amoCAB and hao in the ENI-11 genome.

Locations of the amo and hao genes.

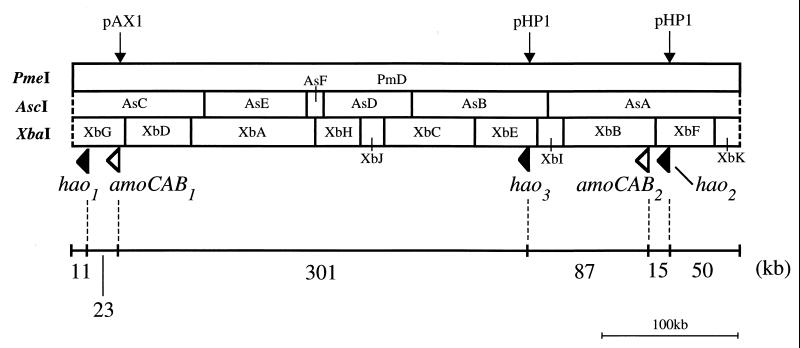

To precisely locate the multiple copies of amoCAB and hao, we first constructed an AscI and XbaI map of PmD (Fig. 2). In the PmD fragment, there existed 5 and 10 restriction sites for AscI and XbaI, respectively (Fig. 2). Southern hybridizations to the AscI digests of PmD were performed with the amoB and hao probes. The amoB probe hybridized to two AscI subfragments, AsA (142 kb) and AsC (96 kb), while the hao probe hybridized to three subfragments, AsA, AsB (100 kb), and AsC (data not shown). These results confirmed the presence of the genes for AMO and HAO in multiple copies in the PmD fragment.

FIG. 2.

AscI and XbaI restriction map of the PmD fragment from the ENI-11 genome. The locations and directions of the multiple copies of amoCAB and hao are shown by white and black arrowheads, respectively. Plasmids pHP1 and pAX1 were used for constructing additional PmeI sites in the PmD fragment. The locations of the pHP1 and pAX1 insertions are indicated by arrows.

We then constructed two mutants, designated NH1 and NH2, by inserting a kanamycin resistance (Kanr) gene cassette into wild-type hao. First, the EcoRI-PmeI-NotI polylinker (5′-GAATTCGACAATTCGTTTAAACTCGCGGCCGC-3′) was inserted into the HincII site of pUC119 to make pPM9. The 2.2-kb PCR fragment, which was used for constructing the hao probe, was digested with XbaI and KpnI and ligated to XbaI- and KpnI-cut pPM9. The resulting plasmid was then digested with HindIII and ligated to HindIII-cut pCRII (Kanr) to make pHP1. pHP1, which carries hao, a PmeI site, and a Kanr marker, was introduced into ENI-11 cells by electroporation. Southern blot analysis revealed that NH1 and NH2 had the pHP1 insertion (5.9 kb) in AsA and AsB, respectively (data not shown). Since pHP1 contained a PmeI site, the PmD fragment from each mutant was split into two new subfragments upon PmeI cleavage. By the PmeI cleavage, the PmD fragment of NH1 was split into subfragments of 443 and 50 kb, while that of NH2 was cut into subfragments of 341 and 152 kb. This result, together with the fact that pHP1 was inserted into either AsA or AsB, indicated that two of three copies of hao, designated hao2 and hao3, were located about 50 and 152 kb from the right end of PmD (Fig. 2). The remaining copy of hao in AsC was designated hao1.

Similarly, another mutant, designated NA1, was constructed by inserting a Kanr gene cassette into wild-type amoB. The 2.3-kb PCR fragment, which was used for constructing the amoB probe, was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and subcloned into pPM9. The resulting plasmid was fused with pCRII to make pAX1. pAX1, which carries amoB, a PmeI site, and a Kanr marker, was also introduced into ENI-11 cells by electroporation. Southern blot analysis revealed that NA1 had the pAX1 insertion (5.1 kb) in AsC (data not shown). By the PmeI cleavage, the PmD fragment of NA1 was split into subfragments of 457 and 34 kb. Thus, one of two copies of amoCAB, designated amoCAB1, was located about 34 kb from the left end of PmD (Fig. 2). The remaining copy of amoCAB in AsA was designated amoCAB2.

The sizes of the regions flanked by amoCAB1 and hao1 and by amoCAB2 and hao2 were determined by using the long-PCR technique. PCR primers A1 (5′-GGTTCATTTCAGGTCCTCTGCAAATTGGCC) and H1 (5′-CGGCAAATTCTCTTAAGTGACAGGTTCCGC) were used for amplifying the DNA fragment between amoCAB1 and hao1, while A2 (5′-CCGAATGCGGTAACATCATTGCGATGTACG) and H2 (5′-AGGATCGATTGGTACTCTGTTGACAGGAGC) were used for the amplification of the DNA region between amoCAB2 and hao2. PCR with primers A1 and H1 amplified a 23-kb product, indicating that hao1 is about 23 kb from amoCAB1. Likewise, PCR with primers A2 and H2 amplified a 15-kb product, indicating that amoCAB2 is about 15 kb from hao2. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 2, hao1 and hao2 were located relatively close to amoCAB1 and amoCAB2, respectively. Only hao3 was at least 75 kb from the duplicated amoCAB. The direction of each copy of amoCAB and hao was suggested by determining the DNA sequences of both ends of the PCR products as well as that of the hao3 region of AsB (Fig. 2).

Characterization of the hao regions.

Localization of the three copies of hao allowed us to determine the copy-specific DNA sequences. Nucleotide sequences were determined by the dideoxy chain termination method using an Auto Cycle kit (Pharmacia) and an ALFred DNA sequencer (Pharmacia). The three copies of hao differed from each other by only 1 or 2 bp in the 1,713-bp sequence (data not shown). Compared with the nucleotide sequence of hao2, hao1 had C instead of T at position 521 and hao3 had C instead of T at position 290 and A instead of G at position 445. In addition, the cycA gene, encoding cytochrome c-554, and the cycB gene, encoding the integral membrane tetraheme cytochrome (1), were also present in three and two copies, respectively (data not shown). Each copy of cycA and cycB existed downstream of hao2 and hao3, while hao1 was followed by only cycA. The nucleotide sequence of hao3 was identical to the hao sequence determined by Sayavedra-Soto et al. (15).

We expected that the intergenic regions between amoCAB and hao might contain additional genes required for ammonia oxidation in this organism. Thus, we partially determined the DNA sequences in these intergenic regions by using the long-PCR technique (data not shown). In the 15-kb DNA region between amoCAB2 and hao2, we found genes which were predicted to encode threonine-tRNA ligase (thrS), initiation factor 3 (infC), ribosomal protein L20 (rplT), the phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase α-subunit (pheS), and the phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase α-subunit (pheT). Concerning the 23-kb region between amoCAB1 and hao1, the rpoB and rpoC genes, encoding the β-subunit and β′-subunit of RNA polymerase, were found to exist closely upstream of hao1. However, we could not find any genes that are required for ammonia oxidation in the partial DNA sequencing.

Analysis of the upstream region of each copy of hao revealed that the three copies of hao shared 15 identical nucleotides immediately upstream of each translation initiation codon. A candidate Shine-Dalgarno sequence, GGAGG, was located in this conserved region (7 bp upstream of each start codon). Furthermore, hao1 and hao2 had a perfect match in the 160 bp of DNA sequence immediately upstream of each translation initiation codon. However, hao3 showed only 30% nucleotide identity in the 160-bp corresponding region. The 350 bp of DNA sequence immediately upstream of the hao3 start codon was identical to that reported previously for N. europaea hao (15). A short open reading frame, of 261 bp, was also detected 30 bp upstream of the hao3 start codon. The 261-bp open reading frame encoded a possible polypeptide which had 43% amino acid identity with E. coli ribosomal protein S20 (9). Conversely, a number of stop codons were present in the 160-bp DNA sequence conserved between hao1 and hao2, and no significant structural features or homologies were detected in this region. These results suggest that hao3, which was located apart from the duplicated amoCAB, may also differ from hao1 and hao2 with respect to transcriptional regulation.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The hao region sequences reported here have been deposited in the GSDB, DDBJ, EMBL and NCBI nucleotide sequence databases under accession numbers AB030385, AB030386, and AB0303387.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergmann D J, Hooper A B. Sequence of the gene, amoB, for the 43-kDa polypeptide of ammonia monooxygenase of Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:759–762. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann D J, Arciero D M, Hooper A B. Organization of the hao gene cluster of Nitrosomonas europaea: genes for two tetraheme c cytochromes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3148–3153. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3148-3153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock E, Koops H-P, Ahlers B, Harms H. Oxidation of inorganic nitrogen compounds as energy source. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 414–430. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu G, Vollrath D, Davis R W. Separation of large DNA molecules by contour clamped homogeneous electric fields. Science. 1986;234:1582–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.3538420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hommes N G, Sayavedra-Soto L A, Arp D J. Mutagenesis of hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in Nitrosomonas europaea by transformation and recombination. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3710–3714. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3710-3714.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hommes N G, Sayavedra-Soto L A, Arp D J. Mutagenesis and expression of amo, which codes for ammonia monooxygenase in Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3353–3359. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3353-3359.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyman M R, Wood P M. Suicidal inactivation and labelling of ammonia mono-oxygenase by acetylene. Biochem J. 1985;227:719–725. doi: 10.1042/bj2270719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klots M G, Alzerreca J, Norton J M. A gene encoding a membrane protein exists upstream of the amoA/amoB genes in ammonia oxidizing bacteria: a third member of the amo operon? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackie G A. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for ribosomal protein S20 and its flanking regions. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8177–8182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McTavish H, LaQuier F, Arciero D, Logan M, Mundfrom G, Fuchs J A, Hooper A B. Multiple copies of genes coding for electron transport proteins in the bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2445–2447. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2445-2447.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McTavish H, Fuchs J A, Hooper A B. Sequence of the gene coding for ammonia monooxygenase in Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2436–2444. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2436-2444.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson T C, Hooper A B. Energy coupling in the bacterial oxidation of small molecules: an extracytoplasmic dehydrogenase in Nitrosomonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;19:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Röming U, Dietmar G, Wilfred B, Burkhard T. A physical genome map of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. EMBO J. 1989;8:4081–4089. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayavedra-Soto L A, Hommes N G, Arp D J. Characterization of the gene encoding hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:504–510. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.504-510.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz D C, Cantor C R. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell. 1984;37:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi R, Kondo N, Usui K, Kanehira T, Shinohara M, Tokuyama T. Pure isolation of a new chemoautotropic ammonia-oxidizing bacterium on gellan gum plate. J Ferment Bioeng. 1992;74:52–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood P M. Nitrification as a bacterial energy source. In: Prosser J I, editor. Nitrification. Oxford, England: Society for General Microbiology and IRL Press; 1986. pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamagata A, Kato J, Hirota R, Kuroda A, Ikeda T, Takiguchi N, Ohtake H. Isolation and characterization of two cryptic plasmids in the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosomonas sp. strain ENI-11. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3375–3381. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3375-3381.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]