Abstract

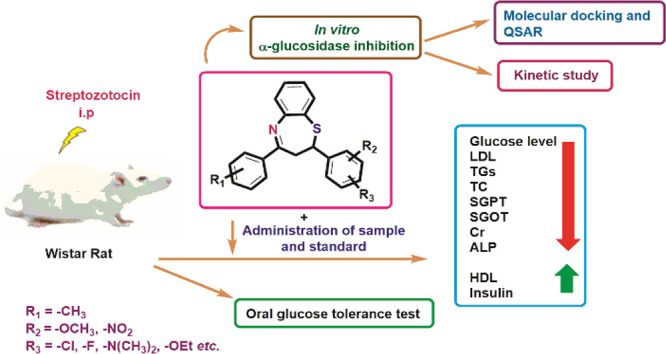

In the present study, a series of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives 1B–14B has been synthesized sand characterized by various spectroscopic techniques. The enzyme inhibitory activities of the target analogues were assessed using in vitro and in vivo mechanism-based assays. The tested compounds 1B–14B exhibited in vitro inhibitory potential against α-glucosidase with IC50 = 2.62 ± 0.16 to 10.11 ± 0.32 μM as compared to the standard drug acarbose (IC50 = 37.38 ± 1.37 μM). Kinetic studies of the most active derivatives 2B and 3B illustrated competitive inhibitions. Based on the α-glucosidase inhibitory effect, the compounds 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B were chosen in vivo for further evaluation of antidiabetic activity in streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. All these evaluated compounds demonstrated significant antidiabetic activity and were found to be nontoxic in nature. Moreover, the molecular docking study was performed to elucidate the binding interactions of most active analogues with the various sites of the α-glucosidase enzyme (PDB ID 3AJ7). Additionally, quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) studies were performed based on the α-glucosidase inhibitory assay. The value of correlation coefficient (r) 0.9553 shows that there was a good correlation between the 1B–14B structures and selected properties. There is a correlation between the experimental and theoretical results. Thus, these novel compounds could serve as potential candidates to become leads for the development of new drugs provoking an anti-hyperglycemic effect.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by complete or partial insulin insufficiency, which leads to imbalanced carbohydrate metabolism.1−3 Many DM patients suffer from serious complications, including eyesight difficulties, nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy, amputation, cardiovascular diseases, etc.4 It is a long-term endocrine system dysfunction caused by insulin resistance (type-2 diabetes) or insulin secretion (type-1 diabetes) abnormalities. Type-1 and type-2 diabetes are the two most common forms of this disease, accounting for almost 90% of all cases.5,6 Globally, this condition affects millions of individuals, and the number of patients is anticipated to rise above 642 million by 2040.7−9 Diabetes type-2 and its long-term consequences have created a public health emergency that necessitates the development of new chemotherapies with improved safety profiles.10 Exercise and a healthy diet are temporary alternative remedies to control hyperglycemia.11−13

Moreover, glycemic control in type-2 diabetes could also be achieved by inhibiting the α-glucosidase enzyme with effective inhibitors.14−16 α-Glucosidase is a membrane-bound carbohydrate digesting enzyme found in the epithelial wall of the small intestine, and its inhibitors play a crucial role for the treatment of DM by decreasing the glucose level in the bloodstream.17,18 α-Glucosidase inhibitors prevent the hydrolysis of the α-1,4-glycosidic bond of complex carbohydrates and delay monosaccharide (α-d-glucose) absorption, which is mainly responsible in causing hyperglycemia.19−24 Thus, α-glucosidase inhibitors have been considered as the most attractive therapeutic target for drug discovery in the treatment of type-2 diabetes.25−30 Despite this, it is thought that inhibiting the α-glucosidase enzyme is a useful therapeutic method for the treatment of type-2 diabetes.31 In this context, acarbose, miglitol, metformin, voglibose, etc. are currently the only clinically licensed medications that can be used as monotherapy or in conjunction with insulin or other oral medications in the treatment of type-2 diabetes.32,33 When these medications are taken regularly, they might cause unpleasant gastrointestinal side effects such as diarrhea, abdominal bloating, pain, and flatulence.34−36 Based on the biological importance of α-glucosidase and the inefficiencies of existing drugs, the development of new α-glucosidase inhibitors is still an interesting target in medicinal chemistry research.37−41

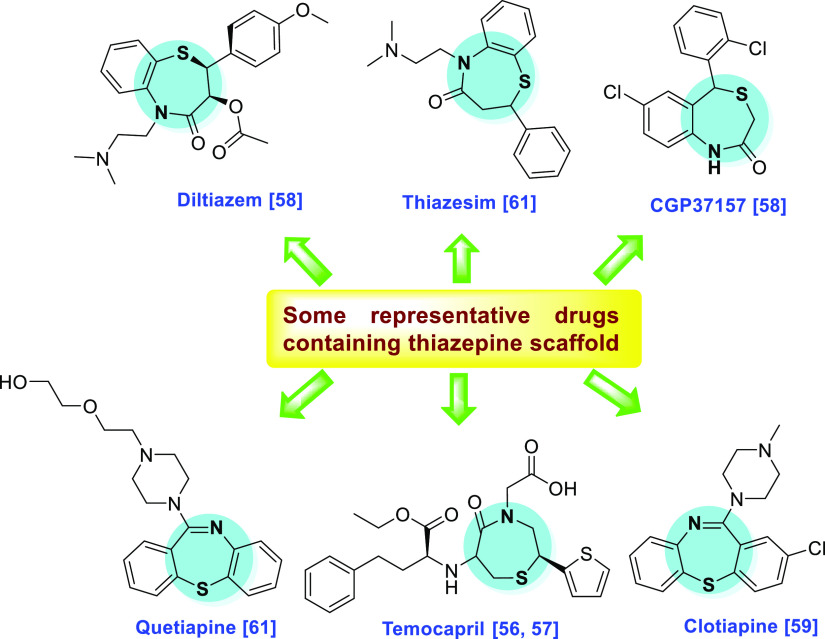

In recent years, organic synthetic chemistry is a rapidly growing area of chemistry research. The N- and S-containing heterocyclic scaffolds have drawn the great interest of medicinal chemists due to their remarkable chemistry and varied biological and pharmacological activities.42−48 In this category, thiazepine and its derivatives are one of the key structural units in numerous medicinally important compounds that have various pharmacological effects.49−55 This scaffold is also found in the structure of various commercially available drugs such as temocapril,56,57 diltiazem,58 clotiapine,59 clentiazem,60 and thiazesim (Figure 1).61−63

Figure 1.

Some reported drugs containing the thiazepine skeleton.

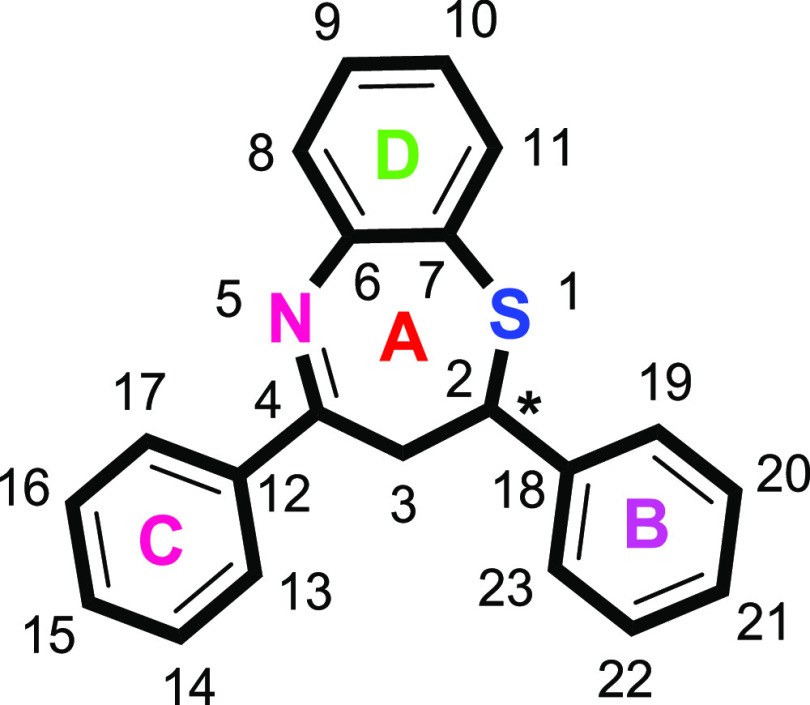

Benzothiazepine (2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine) (Figure 2) is an attractive pharmacophore in medicinal and pharmaceutical chemistry and is considered as a derivative of thiazepine. This scaffold plays a unique role in drug discovery program as its derivatives display a wide spectrum of bioactivities such as antimicrobial, antifeedant, analgesic, anticonvulsant, calcium antagonist, CNS depressant, antiplatelet aggregator, anti-HIV, calmodulin antagonist, and bradykinin receptor antagonist.52,64−77

Figure 2.

Structural representation of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines.

The synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine has gained a lot of interest due to their numerous pharmacological and biological activities. The last decade has seen substantial developments in the chemistry of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine, resulting in a variety of innovative and interesting synthetic methods to construct this structural motif.78,79

Encouraged by the medicinal/pharmaceutical significance of the benzothiazepine motif and in continuation of our interest in developing new anti-α-glucosidase agents, herein, we report the synthesis of novel 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines as the most potent α-glucosidase inhibitors. To the best of our knowledge, this heterocyclic core has not been explored deeply against α-glucosidase. All the synthesized compounds were evaluated for their in vitro against α-glucosidase and, for the first time, in vivo anti-diabetic inhibitory activities. The inhibition mode of the synthesized compounds was determined by kinetic studies. In silico studies were also performed on these compounds to better investigate their interactions with the active site of α-glucosidase. The QSAR studies were also carried out to find out the correlation between the antidiabetic/antihyperglycemic activity and physicochemical properties of synthesized 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

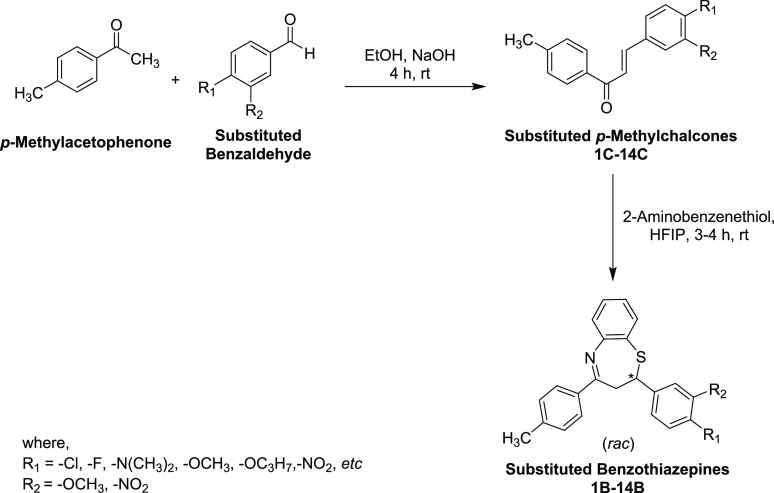

One of the most widely employed methods for the preparation of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines involves the reaction of o-aminothiophenol with chalcones under acidic or basic conditions.52,91,92 Despite numerous methods are available in the literature for synthesizing benzothiazepines, we used a recently reported procedure,79 which involves the 1,4-conjugate addition of o-aminothiophenol to chalcones in the presence of hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) as solvent. This method proved to be superior to other methods in terms of high yields involving the use of strongly acidic or basic conditions in terms of safer handling, high yield, easy work-up, and green effects. The high ionization power, strong hydrogen bonding ability, moderate nucleophilicity, and mild acidic character of HFIP (pKa = 9.2) appears to be customized to activate both the Michael acceptor during the conjugate addition and the carbonyl group in the cyclization step.

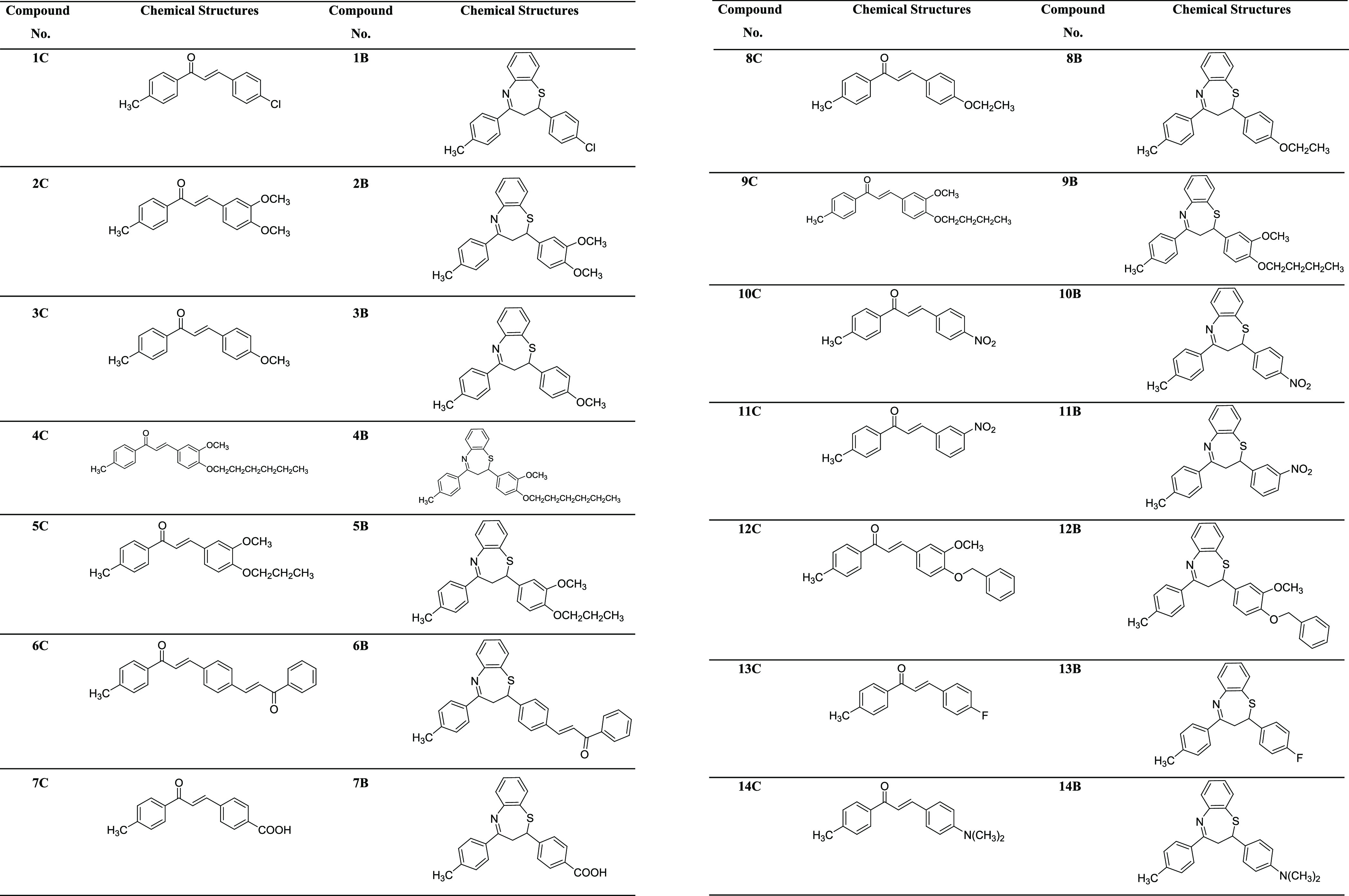

In this context, chalcones 1C–14C were prepared by the Claisen–Schmidt condensation reaction of p-methylacetophenone with variously substituted aromatic aldehydes under a basic medium in excellent yields (Scheme 1). These intermediate compounds were purified by recrystallization in ethanol (EtOH) and thereafter characterized by IR, UV–vis, and NMR spectroscopy. Subsequently, the target compounds 1B–14B were synthesized by Michael’s addition of 2-aminobenzenethiol to substituted chalcones in HFIP solvent at ambient temperature in moderate to good yields. Of note, these final compounds were obtained as racemates. The desired compounds 1B–14B (Table 1) were purified through recrystallization in EtOH. The formation of all the target compounds 1B–14B was elucidated by UV–vis, FT-IR, and NMR spectroscopic techniques. All these analytical techniques have unequivocally corroborated the structures of all newly synthesized benzothiazepines.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Chalcones 1C–14C and 2,3-Dihydro-1,5-Benzothiazepines 1B–14B.

Table 1. Chemical Structures of Chalcones 1C–14C and 2,3-Dihydro-1,5-Benzothiazepines 1B–14B.

2.2. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

It is apparent from the results in Table 2 that the analogues 1B–14B demonstrated promising inhibitory activity against the α-glucosidase enzyme to a greater extent. All the target compounds were found to be more active as compared to the standard. Among the tested compounds, the maximum activity was shown by the 2B derivative with the lowest IC50 of 2.62 ± 0.30 μM, whereas the minimum activity was given by the compound 11B, having an IC50 value of 10.11 ± 0.84 μM. Compounds 6B and 7B produced nearly the same activity having IC50 values of 3.63 ± 0.36 and 3.96 ± 0.42 μM, respectively. Acarbose was used as standard with IC50 = 37.38 ± 1.37 μM.

Table 2. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Efficacy of the Synthesized Derivatives 1B–14Ba.

| compound no. | glucosidase inhibitionIC50 ± SEMa (μM) | compound no. | glucosidase inhibitionIC50 ± SEMa (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 4.33 ± 0.41 | 8B | 9.44 ± 0.83 |

| 2B | 2.62 ± 0.30 | 9B | 8.56 ± 0.59 |

| 3B | 3.01 ± 0.29 | 10B | 9.01 ± 0.77 |

| 4B | 8.76 ± 0.62 | 11B | 10.11 ± 0.84 |

| 5B | 6.28 ± 0.71 | 12B | 3.79 ± 0.22 |

| 6B | 3.63 ± 0.36 | 13B | 3.28 ± 0.19 |

| 7B | 3.96 ± 0.42 | 14B | 3.34 ± 0.27 |

| acarbose (standard) | 37.38 ± 1.37 |

IC50 values (mean ± standard error of the mean); Standard: Standard inhibitor for glucosidase.

2.3. Acute Toxicity

The results obtained by the compounds 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B demonstrated no mortality when animals were challenged to a maximum oral dose of 2000 mg/kg (b.w.). Animals were checked daily for observing signs of diarrhea, convulsions, lethargy, sleeping, salivation, and tremor for 2 weeks, and no toxic effects were found. With the toxicity data in sight (200 mg/kg as 1/10th of the maximum dose), effective doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg doses for the derivatives 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B were selected for behavioral studies after preliminary pharmacological assessment in our laboratory.

2.4. Effect of Synthetic Benzothiazepines on Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

After the administration of glucose (3 g/kg, oral) to the animals under observation, the serum glucose level in the group reached to maximum level peak after 30 min and gradually decreased to 128.70 ± 4.89 mg/dL after 2 h. The pretreatment with synthetic benzothiazepines 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B (10 and 20 mg/kg) and glibenclamide brought out a decline in the serum glucose level significantly as compared to the control group (Table 3).

Table 3. Effect of the Tested Synthetic Benzothiazepines on Blood Glucose in OGTTa.

| blood glucose level in mg/dL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| groups | dose (mg/kg) | 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min |

| control group (sugar-treated) | 106.23 ± 4.91 | 177.26 ± 5.01!!! | 154.82 ± 4.91!!! | 135.21 ± 4.82!!! | 128.87 ± 4.89!!! | |

| 2B | 10 | 103.21 ± 4.13 | 118.61 ± 4.57* | 113.31 ± 5.03* | 111.90 ± 4.57* | 109.20 ± 4.39 |

| 20 | 101.38 ± 4.67 | 115.07 ± 4.61** | 109.39 ± 4.56* | 108.69 ± 4.11** | 107.78 ± 4.75 | |

| 3B | 10 | 103.09 ± 4.03 | 119.71 ± 4.01* | 119.98 ± 4.97* | 115.92 ± 4.01* | 111.82 ± 4.45 |

| 20 | 101.33 ± 4.11 | 116.21 ± 4.45* | 117.03 ± 4.71* | 109.31 ± 4.21** | 113.15 ± 4.13 | |

| 6B | 10 | 103.41 ± 4.05 | 125.39 ± 4.10* | 120.41 ± 4.81* | 112.61 ± 4.81* | 114.91 ± 4.59 |

| 20 | 100.93 ± 4.11 | 119.91 ± 4.62* | 121.66 ± 4.31* | 111.22 ± 4.21* | 109.78 ± 5.01 | |

| 7B | 10 | 104.01 ± 4.97 | 120.71 ± 5.01* | 120.90 ± 4.54* | 116.52 ± 4.11* | 109.25 ± 4.91 |

| 20 | 103.88 ± 4.04 | 117.41 ± 4.70** | 114.22 ± 4.97** | 117.01 ± 4.66* | 108.91 ± 4.87 | |

| 12B | 10 | 101.67 ± 4.55 | 121.63 ± 4.56* | 122.02 ± 4.66* | 115.31 ± 4.61* | 114.19 ± 4.61 |

| 20 | 105.59 ± 4.61 | 117.38 ± 4.01* | 117.61 ± 4.60* | 110.71 ± 4.91** | 111.21 ± 4.31 | |

| 13B | 10 | 104.80 ± 4.97 | 120.04 ± 5.04* | 118.31 ± 4.65* | 109.81 ± 4.56** | 113.93 ± 4.67 |

| 20 | 103.79 ± 5.12 | 116.81 ± 4.31** | 114.98 ± 4.34** | 110.21 ± 3.91** | 110.04 ± 4.81 | |

| 14B | 10 | 104.21 ± 4.67 | 124.02 ± 4.01* | 119.33 ± 4.63* | 114.98 ± 4.03* | 116.49 ± 4.71 |

| 20 | 103.87 ± 4.18 | 119.61 ± 4.55* | 116.20 ± 4.78** | 112.69 ± 4.11* | 111.61 ± 4.97 | |

| std | 0.5 | 102.03 ± 4.22 | 103.92 ± 5.01** | 108.71 ± 4.21*** | 101.86 ± 4.21*** | 104.12 ± 4.67 |

All values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 8. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison test determines the values of P. !!!P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs normal control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs test samples and glibenclamide-treated groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s comparison.

2.5. Antidiabetic Activity

The blood serum glucose level results of control (normal and diabetic) and diabetic treated with different compounds and glibenclamide are displayed in Table 4. The oral administration of compound 2B (10 and 20 mg/kg) caused a significant (***P < 0.001, n = 8) reduction in the level of blood glucose compared to diabetic control. The same compound 2B decreased the level of blood glucose from 379.31 ± 4.98 to 286.09 ± 4.31 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w. and 379.31 ± 4.98 to 225.33 ± 4.87 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg b.w. and the effect was evident from the seventh day onward while a significant effect was produced on the 14th day of study (188.21 ± 4.32 and 155.09 ± 4.55 mg/dL ,respectively). On the second day, the result was more promising (144.31 ± 4.34 and 120.42 ± 4.88 mg/dL).

Table 4. Effect on Blood Glucose in STZ-Induced Diabetesa.

| blood

glucose level in mg/dL |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| groups | dose (mg/kg) | day 1 | day 7 | day 14 | day 21 | day 28 |

| normal control | 109.36 ± 4.70 | 109.43 ± 3.96 | 110.71 ± 4.88 | 108.81 ± 5.28 | 106.46 ± 5.11 | |

| diabetic control | 380.21 ± 5.29!!! | 379.31 ± 4.98!!! | 388.62 ± 5.03!!! | 401.08 ± 5.71!!! | 392.16 ± 5.02!!! | |

| 2B | 10 | 376.21 ± 4.23 | 286.09 ± 4.31* | 188.21 ± 4.32** | 144.31 ± 4.34** | 127.81 ± 4.23** |

| 20 | 381.09 ± 4.21 | 225.33 ± 4.87** | 155.09 ± 4.55** | 120.42 ± 4.88*** | 104.15 ± 3.99*** | |

| 3B | 10 | 373.11 ± 4.11 | 291.80 ± 4.71* | 190.87 ± 4.07* | 147.62 ± 5.01** | 132.11 ± 4.03** |

| 20 | 380.35 ± 5.08 | 234.78 ± 4.61** | 161.42 ± 4.12** | 122.56 ± 4.70*** | 105.32 ± 4.09*** | |

| 6B | 10 | 381.40 ± 4.30 | 280.90 ± 4.66* | 205.31 ± 4.01* | 150.45 ± 4.92** | 135.67 ± 3.89** |

| 20 | 380.30 ± 4.78 | 228.44 ± 5.06** | 166.09 ± 4.46** | 129.71 ± 4.09** | 111.81 ± 4.08*** | |

| 7B | 10 | 377.08 ± 5.01 | 290.20 ± 4.93 | 215.76 ± 5.03* | 153.19 ± 4.66* | 136.51 ± 5.19** |

| 20 | 374.21 ± 4.12 | 238.39 ± 5.11** | 171.44 ± 4.98* | 134.20 ± 5.03*** | 112.97 ± 4.56*** | |

| 12B | 10 | 371.67 ± 4.66 | 301.41 ± 4.56* | 209.60 ± 4.22* | 152.56 ± 4.71* | 138.92 ± 4.67* |

| 20 | 369.56 ± 4.56 | 237.11 ± 4.39** | 167.49 ± 5.02** | 131.69 ± 4.77** | 114.74 ± 5.09*** | |

| 13B | 10 | 370.81 ± 4.79 | 289.89 ± 4.33* | 200.33 ± 4.57** | 149.30 ± 4.56** | 132.98 ± 4.33** |

| 20 | 375.31 ± 5.01 | 230.71 ± 4.88** | 163.68 ± 4.37** | 120.72 ± 4.11*** | 108.42 ± 3.98*** | |

| 14B | 10 | 369.82 ± 4.12 | 294.04 ± 4.67 | 196.39 ± 4.12** | 151.11 ± 4.39* | 134.20 ± 4.21** |

| 20 | 370.33 ± 3.98 | 231.69 ± 5.20** | 158.26 ± 4.67** | 127.21 ± 4.81*** | 109.71 ± 4.23*** | |

| std | 0.5 | 352.28 ± 4.11 | 231.12 ± 4.29** | 151.43 ± 4.09** | 118.87 ± 4.03*** | 101.68 ± 4.19*** |

All values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 8. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison test determines the values of P. !!!P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs normal control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs test samples and glibenclamide-treated groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s comparison.

Similarly, other compounds such as 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B were also tested at 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w. level, and the obtained results showed a significant fall in serum glucose level in the tested animals. Among the tested compounds, the derivative 6B demonstrated promising results, and on the seventh day, at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w., the blood glucose level decreased substantially from 379.34 ± 4.98 to 280.90 ± 4.66 and 228.44 ± 5.06 mg/dL, respectively. On the 14th day of the study under the same dose, the obtained results were in the range of 205.31 ± 4.01 and 166.09 ± 4.46 mg/dL, respectively. On the 21st day, the blood glucose level was lowered to a significant value (150.45 ± 4.92 and 129.71 ± 4.09).

The results of all compounds were more promising and appealing on the 28th day; by administrating doses of 10 mg/kg b.w., compound 2B produced a result of 127.81 ± 4.23. Additionally, the analogue 3B had a significantly lowered blood glucose level of 132.11 ± 4.03. This result is comparable to the derivative 13B (132.98 ± 4.33). In contrast to all the tested compounds, the least activity was produced by 12B, which was 138.92 ± 4.67 followed by the antidiabetic activity of benzothiazepine 14B (134.20 ± 4.21).

However, at a dose of 20 mg/kg, compound 2B lowered the blood glucose level to 104.15 ± 3.99 followed by 3B, which decreased the glucose level to 105.32 ± 4.09. Compound 13B showed very good antidiabetic activity (108.42 ± 3.98). Following that, the analogue 14B manifested the highest antidiabetic activity by decreasing the glucose level to 109.71 ± 4.23. Compound 6B showed activity equal to 111.81 ± 4.08 glucose level followed by the derivative 7B, which delivered an activity of 112.97 ± 4.56. By cross-comparison, compound 12B was the least active among all, producing a result of 114.74 ± 5.09.

2.6. Effects on Body Weight

Changes in the body weight of control and experimental rats treated with compounds and glibenclamide are presented. The diabetic rats with STZ produced a significant loss (**P < 0.01, n = 8) in weight when compared to normal rats (Table 5). The diabetic group continued to lose weight until the end (28 days). In this regard, a 12.1% reduction in weight was observed. The weight loss by STZ was reversed by the envisioned compounds at a dose of 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w.

Table 5. Effect of the Target Compounds on the Body Weights of Ratsa.

| groups | dose (mg/kg) | day 1 | day 7 | day 14 | day 21 | day 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| normal control | 173.1 ± 3.91 | 174.3 ± 4.01 | 174.8 ± 4.19 | 173.8 ± 4.09 | 176.1 ± 4.12 | |

| diabetic control | 180.2 ± 4.39 | 161.9 ± 4.12!! | 157.1 ± 4.37!!! | 154.2 ± 4.81!!! | 148.4 ± 4.01!!! | |

| glibenclamide | 0.5 | 187.4 ± 4.57 | 190.2 ± 3.98* | 177.1 ± 4.21* | 183.7 ± 4.33** | 185.1 ± 4.48** |

| 2B | 10 | 187.7 ± 4.61 | 185.1 ± 4.39* | 177.3 ± 4.51** | 179.4 ± 4.16* | 176.6 ± 4.98** |

| 20 | 192.1 ± 4.91 | 191.2 ± 4.39* | 180.1 ± 4.62** | 181.4 ± 3.98* | 181.6 ± 4.66** | |

| 3B | 10 | 191.3 ± 4.11 | 189.1 ± 4.31* | 186.5 ± 4.19** | 180.4 ± 4.76* | 177.3 ± 4.88** |

| 20 | 198.1 ± 4.66 | 193.0 ± 4.18* | 187.9 ± 4.21** | 184.1 ± 4.13* | 183.2 ± 4.68** | |

| 6B | 10 | 190.0 ± 3.98 | 182.5 ± 4.19* | 187.1 ± 4.88** | 183.4 ± 4.60* | 180.9 ± 4.23** |

| 20 | 194.1 ± 4.41 | 189.3 ± 4.61* | 190.3 ± 4.71** | 186.7 ± 3.96* | 184.3 ± 4.33** | |

| 7B | 10 | 191.1 ± 4.07 | 188.2 ± 4.57* | 185.6 ± 4.90** | 184.1 ± 4.71* | 183.7 ± 4.32** |

| 20 | 188.9 ± 4.67 | 190.8 ± 4.21* | 188.1 ± 4.62** | 185.2 ± 3.91* | 186.1 ± 4.58** | |

| 12B | 10 | 187.5 ± 4.39 | 185.1 ± 4.71* | 184.5 ± 4.06** | 187.0 ± 4.39* | 173.9 ± 4.28** |

| 20 | 189.7 ± 4.08 | 184.7 ± 4.66** | 187.1 ± 4.11** | 189.3 ± 4.60** | 175.3 ± 5.01** | |

| 13B | 10 | 186.6 ± 4.70 | 183.4 ± 4.15* | 186.3 ± 4.22** | 180.1 ± 4.12* | 177.3 ± 4.40** |

| 20 | 193.6 ± 4.21 | 187.2 ± 4.81* | 191.1 ± 4.14** | 187.8 ± 3.99* | 185.7 ± 4.79** | |

| 14B | 10 | 188.5 ± 4.07 | 186.8 ± 4.39* | 187.1 ± 4.33** | 181.6 ± 4.21* | 179.3 ± 4.41** |

| 20 | 189.1 ± 4.19 | 188.5 ± 4.21* | 189.2 ± 4.66** | 183.4 ± 4.18* | 182.5 ± 4.58** |

All values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 8. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison test determines the values of P. !!!P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs normal control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs test samples and glibenclamide-treated groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s comparison.

2.7. Effects on Lipid Profiles

The lipid profile data of each tested animal was obtained to figure out the side effects of the administered compounds. The obtained lipid profile results are given in Table 6. In the diabetic group, a significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01,***P < 0.001, n = 8) increase in the total cholesterol (CH), TGs, and LDL was observed as compared to the normal group of animals. In addition, there was a substantial decrease (*P < 0.05, n = 8) in HDL levels in diabetic rats. Administration of compounds at 10 and 20 mg/kg for 4 weeks (28 days) exhibited a considerable (*P < 0.05,**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 8) reduction in TGs, total cholesterol, and LDL in comparison to the diabetic group that was comparable to standard drugs.

Table 6. Antihyperlipidemic Effects on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetesa.

| groups | dose mg/kg | total CH (mg/dL) | HDL (mg/dL) | LDL (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| normal control | 120.33 ± 4.91 | 67.63 ± 2.11 | 94.31 ± 4.29 | 92.73 ± 4.45 | |

| diabetic control | 226.03 ± 5.47!!! | 24.87 ± 2.96!!! | 183.30 ± 4.56!!! | 189.35 ± 4.29!!! | |

| glibenclamide | 0.5 | 122.09 ± 4.89** | 65.90 ± 2.71** | 96.12 ± 4.31*** | 105.43 ± 4.31** |

| 2B | 10 | 147.19 ± 4.71* | 47.98 ± 2.51* | 120.51 ± 4.67*** | 140.24 ± 4.39* |

| 20 | 133.10 ± 4.21* | 58.41 ± 2.80*** | 104.31 ± 4.08*** | 112.04 ± 4.17** | |

| 3B | 10 | 147.98 ± 4.56* | 47.50 ± 2.22* | 122.71 ± 4.11*** | 142.22 ± 4.39* |

| 20 | 133.19 ± 4.22* | 55.21 ± 3.67** | 106.27 ± 4.13*** | 113.41 ± 4.15** | |

| 6B | 10 | 151.07 ± 4.92 | 44.89 ± 3.01* | 130.21 ± 3.99*** | 145.21 ± 4.98* |

| 20 | 137.11 ± 3.71** | 52.07 ± 2.69* | 113.41 ± 4.71 | 116.82 ± 4.41 | |

| 7B | 10 | 153.38 ± 3.69** | 45.89 ± 2.98* | 133.26 ± 4.16*** | 148.27 ± 4.21* |

| 20 | 136.40 ± 3.81** | 53.92 ± 2.13* | 114.18 ± 4.10*** | 118.61 ± 4.71* | |

| 12B | 10 | 152.11 ± 4.11** | 45.91 ± 2.70** | 134.89 ± 4.33*** | 149.81 ± 4.60* |

| 20 | 136.03 ± 4.39* | 53.24 ± 2.08* | 113.71 ± 4.16*** | 117.97 ± 4.01** | |

| 13B | 10 | 148.67 ± 4.11* | 46.29 ± 2.01* | 127.81 ± 4.39*** | 142.93 ± 4.21* |

| 20 | 134.21 ± 4.77* | 56.08 ± 2.63** | 108.91 ± 4.11*** | 114.81 ± 4.41** | |

| 14B | 10 | 149.08 ± 4.12** | 45.25 ± 2.15* | 129.08 ± 4.06*** | 144.11 ± 4.39* |

| 20 | 135.11 ± 4.02** | 55.21 ± 2.66* | 110.41 ± 3.90*** | 115.24 ± 4.13** |

All values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 8. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison test determines the values of P. !!!P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs normal control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs test samples and glibenclamide-treated groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s comparison.

Compound 2B lowered the total CH to the level of 226.03 ± 5.47 to 147.19 ± 4.71 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w. and to 133.10 ± 4.21 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg b.w., The compound 3B also nearly produced the same result as 2B and thus lowered the total CH from 226.03 ± 5.47 to 147.98 ± 4.56 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w. and 133.19 ± 4.22 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg b.w. Following this, the analogue 14B lowered the total CH from 226.03 ± 5.47 to 149.08 ± 4.12 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w. and to 135.11 ± 4.02 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg b.w. The derivatives 6B, 7B, and 13B also lowered the total CH level considerably. Among all the compounds, the benzothiazepine 12B exhibited the least activity, lowering the total CH from 226.03 ± 5.47 to 152.11 ± 4.11 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w. and 136.03 ± 4.39 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg b.w.

All the tested compounds significantly increased HDL values in comparison to the diabetic group. Among all the tested compounds, the derivative 2B elevated the HDL value considerably from 24.87 ± 2.96 to 47.98 ± 2.51 and 58.41 ± 2.80 mg/dL at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w., respectively followed by 3B and 13B. However, the least potent among the series was 6B, which elevated the HDL value suggestively from 24.87 ± 2.96 to 44.89 ± 3.01 and 52.07 ± 2.69 mg/dL at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w., respectively, followed by the sample 12B.

Moreover, the compounds were also tested for LDL analysis. These findings showed that the compound with promising activity was 2B as compared to the normal control as it decreased the LDL value to 96.12 ± 4.31 mg/dL from 183.30 ± 4.56 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg, whereas at a dose of 20 mg/kg, it lowered the LDL value to 104.31 ± 4.08 mg/dL. The compound 3B lessened the LDL level to 122.71 ± 4.11 and 106.27 ± 4.13 mg/dL at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w., respectively. Compound 12B appeared to be the least active among the tested compounds and lowered the LDL levels to 134.89 ± 4.33 and 113.71 ± 4.16 mg/dL at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w., respectively.

Triglyceride (TG) levels were also examined, and it was found that all the compounds lowered the TG levels in diabetic animals. Compound 2B was the prominent one that lowered the TG level from 189.35 ± 4.29 to 140.24 ± 4.39 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg and 112.04 ± 4.17 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg. The next most potent compound was 3B. The derivative 7B appeared to be the least potent among all the tested samples. This lowered the TG level from 189.35 ± 4.29 to 148.27 ± 4.21 mg/dL at a dose of 10 mg/kg and 118.61 ± 4.71 mg/dL at a dose of 20 mg/kg, followed by analogue 14B (Table 5).

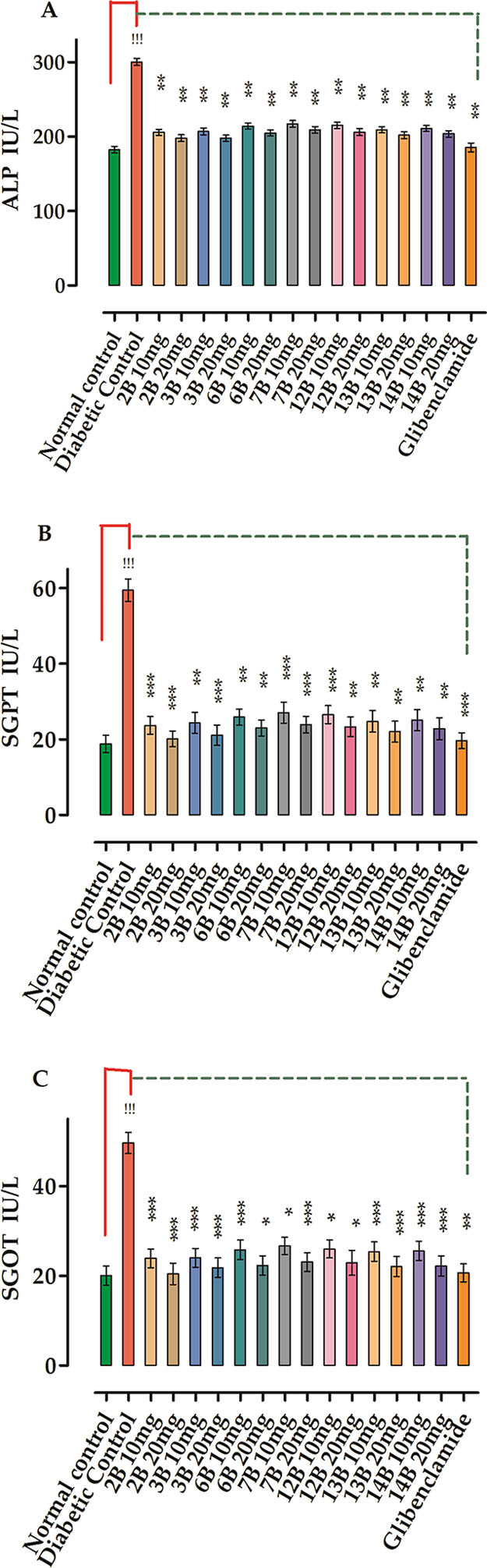

2.8. Effects on Liver Function in STZ-Induced Diabetes

Levels of hepatic marker enzymes including alkaline phosphatase, serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase, and serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase in the STZ-induced diabetic group were high and are displayed in Table 7 and Figure 3. Administration of the tested compounds (10 and 20 mg/kg) reduced to a significant level (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 8) of serum biomarkers. There was also a considerable fall in creatinine level (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 8) as compared to the standard glibenclamide.

Table 7. Effects of Compounds on Serum Profilesa.

| groups | dose (mg/kg) | (ALP) IU | (SGPT) IU | (SGOT) IU | serum creatinine (mg/dL) | insulin level (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| normal control | 182.36 ± 4.49 | 18.79 ± 2.29 | 20.07 ± 2.12 | 0.61 ± 0.22 | 0.811 ± 0.35 | |

| diabetic control | 300.12 ± 4.94!!! | 59.43 ± 2.97!!! | 49.67 ± 2.39!!! | 3.01 ± 0.29!!! | 0.369 ± 0.29 | |

| glibenclamide | 0.5 | 185.32 ± 5.71** | 19.63 ± 2.11*** | 20.68 ± 2.01** | 0.57 ± 0.23*** | 0.754 ± 0.33 |

| 2B | 10 | 205.51 ± 4.39** | 23.70 ± 2.30*** | 23.89 ± 2.11*** | 0.71 ± 0.25* | 0.709 ± 0.29 |

| 20 | 197.89 ± 4.34** | 20.12 ± 2.12*** | 20.44 ± 2.29*** | 0.64 ± 0.33* | 0.721 ± 0.37 | |

| 3B | 10 | 206.78 ± 4.67** | 24.35 ± 2.78** | 24.01 ± 2.11*** | 0.73 ± 0.31* | 0.704 ± 0.41 |

| 20 | 197.78 ± 4.19** | 21.09 ± 2.71*** | 21.83 ± 2.16*** | 0.68 ± 0.29** | 0.713 ± 0.37 | |

| 6B | 10 | 214.19 ± 4.11** | 25.90 ± 2.11** | 25.81 ± 2.16*** | 0.82 ± 0.22** | 0.658 ± 0.31 |

| 20 | 204.71 ± 4.13** | 23.01 ± 2.11** | 22.31 ± 2.17* | 0.75 ± 0.30** | 0.667 ± 0.40 | |

| 7B | 10 | 217.14 ± 4.61** | 27.07 ± 2.77*** | 26.71 ± 1.91* | 0.85 ± 0.37** | 0.621 ± 0.37 |

| 20 | 209.01 ± 4.29** | 23.91 ± 2.21*** | 23.08 ± 2.11*** | 0.79 ± 0.31** | 0.639 ± 0.29 | |

| 12B | 10 | 215.19 ± 4.10** | 26.53 ± 2.38*** | 26.01 ± 2.01* | 0.90 ± 0.30** | 0.651 ± 0.34 |

| 20 | 205.93 ± 4.67** | 23.35 ± 2.54** | 22.91 ± 2.87* | 0.80 ± 0.38** | 0.660 ± 0.30 | |

| 13B | 10 | 208.96 ± 4.22** | 24.76 ± 2.81** | 25.41 ± 2.18*** | 0.76 ± 0.39* | 0.696 ± 0.29 |

| 20 | 201.80 ± 4.71** | 22.03 ± 2.78** | 22.09 ± 2.21*** | 0.70 ± 0.33** | 0.705 ± 0.31 | |

| 14B | 10 | 210.98 ± 4.39** | 25.08 ± 2.78** | 25.56 ± 2.18*** | 0.75 ± 0.36** | 0.690 ± 0.27 |

| 20 | 203.51 ± 4.34** | 22.82 ± 2.91** | 22.20 ± 2.21*** | 0.72 ± 0.30** | 0.697 ± 0.34 |

All values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 8. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison test determines the values of P. !!!P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs normal control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs test samples and glibenclamide-treated groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s comparison.

Figure 3.

Effects of compounds on serum profile: (A) alkaline phosphatase (ALP), (B) serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), and (C) serum glutamic–oxaloacetic transaminase. All values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 8. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparison tests determine the values of P. !!!P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs normal control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 as a comparison of the diabetic control group vs test samples and glibenclamide-treated groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s comparison.

In this study, the compound with promising effects was 2B, which significantly declined (ALP) IU from 300.12 ± 4.94 to 205.51 ± 4.39 and 197.89 ± 4.34 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by the compound 3B with ALP IU decreasing from 300.12 ± 4.94 to 206.78 ± 4.67 and 197.78 ± 4.19 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. The least potent compound among the tested ones was 7B, which produced a decline in results from 300.12 ± 4.94 to 217.14 ± 4.61 and 201.01 ± 4.29 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by the analogue 12B.

The SGPT value was also considered, in which the compound 2B was found the most potent, which significantly lowered the SGPT from 59.43 ± 2.97 to 23.70 ± 2.30 and 20.12 ± 2.12 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by 3B, which lowered the SGPT from 59.43 ± 2.97 to 24.35 ± 2.78 and 21.09 ± 2.71 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. The least potent compound among the tested ones was 7B, which produced a decline in results from 59.43 ± 2.97 to 27.07 ± 2.77 and 23.91 ± 2.21 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by the derivative 12B.

SGOT studies were also carried out, and once again, the compound 2B was found to be the most potent, lowering the SGOT from 49.67 ± 2.39 to 23.89 ± 2.11 and 20.44 ± 2.29 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by 3B, which lowered the SGOT from 49.67 ± 4.39 to 24.01 ± 2.11 and 21.83 ± 2.16 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. The least potent compound among the tested ones was 7B, which produced declines in results from 49.67 ± 2.39 to 26.71 ± 1.91 and 23.08 ± 2.11 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by 12B.

Effects of the compounds on serum creatinine were also studied, and the compound 2B was found to be the most potent, significantly lowering the SGOT from 3.01 ± 0.29 to 0.71 ± 0.25 and 0.64 ± 0.33 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed 3B, which lowered the SGOT from 3.01 ± 0.29 to 0.73 ± 0.31 and 0.68 ± 0.29 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. The least potent compound among the tested ones was 7B, which produced a decline in results from 3.01 ± 0.29 to 0.85 ± 0.37 and 0.79 ± 0.31 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by 12B.

The compounds were also investigated for insulin levels, and in this context, the compound 2B was found to be the most potent, considerably increasing insulin levels from 0.369 ± 0.29 to 0.709 ± 0.29 and 0.721 ± 0.37 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by 3B, which elevated insulin levels from 0.369 ± 0.29 to 0.704 ± 0.41 and 0.713 ± 0.37 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. The least potent compound among the tested samples was 7B, which produced an incline in results from 0.369 ± 0.29 to 0.621 ± 0.37 and 0.639 ± 0.29 at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, followed by the analogue 12B.

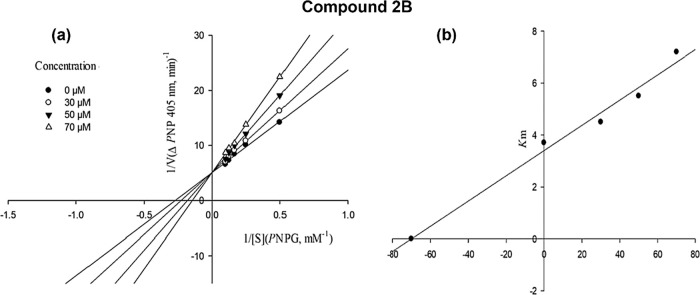

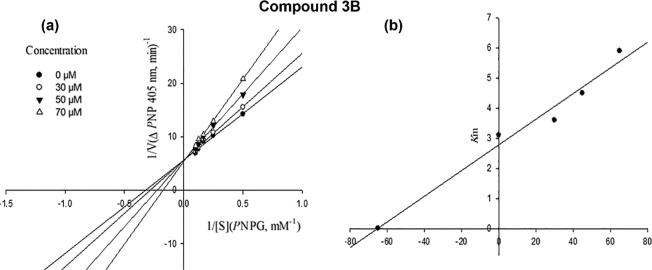

2.9. Kinetic Study Results

To gain further insight into the inhibition mechanism of the synthesized compounds on α-glucosidase, a kinetic study was performed on the most potent compounds 2B and 3B. The kinetic studies were utilized to determine the mode of inhibition of the selected target derivatives.

The competitive mode of inhibition was determined for the most active compound 2B. The unchanged Vmax value and increased Km value, which were determined by the Lineweaver–Burk plot, indicated that compound 2B is bound to the active site and competed with the substrate. Moreover, by drawing the plot of the Km versus different concentrations of inhibitor, an estimated amount of 70 μM was determined for the inhibition constant Ki (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of α-glucosidase inhibition by compound 2B: (a) Lineweaver–Burk plot in the absence and presence of different concentrations of compound 2B; (b) secondary plot between Km and various concentrations of compound 2B.

The mode of inhibition of compound 3B was determined by Lineweaver–Burk plots, and then the Ki was calculated with secondary replotting of the Lineweaver–Burk plots. The analysis of the obtained Lineweaver–Burk plots showed that with increasing concentrations of compound 3B, the Vmax value remained unchanged, while the Km increased. It indicated that compound 3B was a competitive inhibitor and competed with the substrate for binding to the active site of α-glucosidase. Moreover, secondary replotting of the mentioned Lineweaver–Burk plots against the different concentrations of compound 3B provided an estimated Ki value of 87.0 μM for compound 3B (Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

Kinetics of α-glucosidase inhibition by compound 3B: (a) Lineweaver–Burk plot in the absence and presence of different concentrations of compound 3B; (b) secondary plot between Km and various concentrations of compound 3B.

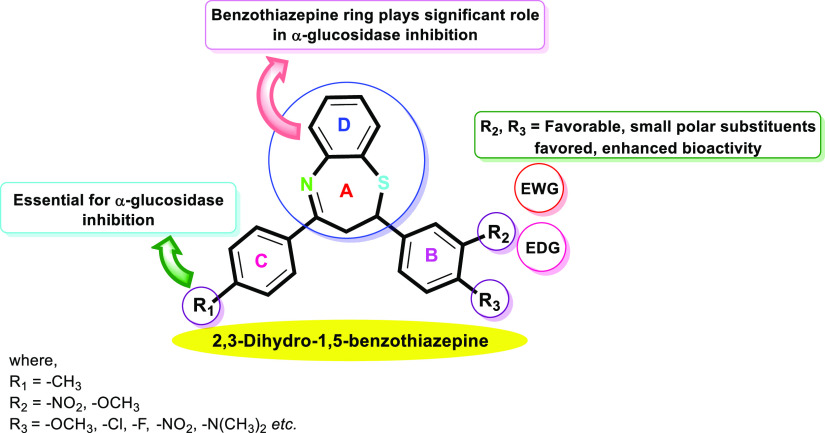

2.10. Structure–Activity Relationships Based on α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity and Docking Studies

Analyzing the SAR of the target derivatives of the 1,5-benzothiazepine-based α-glucosidase inhibitors (Figure 6) gives us a lot of remarkable promising outcomes. The structure–activity relationship was explored depending on the nature and position of substituents present on the phenyl ring B of the 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine motif. Concerning the 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine-based candidates, the α-glucosidase activities of all the synthesized target compounds 1B–14B were found to be superior (IC50 = 2.62 ± 0.16 to 10.11 ± 0.32 μM) as compared to the standard acarbose (IC50 = 37.38 ± 0.6 μM).

Figure 6.

Structure–activity relationship of the synthesized target compounds 1B–14B.

The most potent compound 2B (IC50 = 2.62 ± 0.30 μM) containing electron-donating groups by resonance effect and withdrawing by the inductive effect, i.e., methoxy at meta and para positions on ring B and methyl at a para position on ring C of the 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine skeleton distinctly resulted in increased inhibitory activity and thus was found to be the most potent α-glucosidase inhibitor among all the synthetic 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives.

Furthermore, compound 14B (IC50 = 3.34 ± 0.27 μM) with p-CH3 substitution on ring C and a dimethylamino (-N(CH3)2) substituent on aromatic ring B showed better inhibitory activity as compared to the standard acarbose (IC50 = 37.38 ± 1.37 μM). Similarly, compound 3B (IC50 = 3.01 ± 0.29 μM) bearing p-OCH3, on the aryl ring resulted in increased inhibition due to better interaction with the active pockets of enzymes. The compounds 7B (IC50 = 3.96 ± 0.42 μM) was found to be more active against the envisioned enzyme. The findings reflect that the highly hydrophilic -COOH group on phenyl ring B is accountable for their high activity because of increased interaction with the enzyme.

Additionally, the compounds 4B (IC50 = 8.76 ± 0.62 μM), 5B (IC50 = 6.28 ± 0.71 μM), 6B (IC50 = 3.63 ± 0.36 μM), 8B (IC50 = 9.44 ± 0.83 μM), and 9B (IC50 = 8.56 ± 0.59 μM) containing alkoxy groups (-OCH3, -OC2H5, OC3H7, OC4H9, and OC6H13) as substituents that are electron-withdrawing in nature by the inductive effect of the oxygen atom and act as electron-donating by resonance effect, thus resulting in moderate to excellent inhibitory activities against the envisioned enzyme as compared to the standard acarbose. Notably, all these derivatives demonstrated excellent inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase enzyme, even many times more active than the positive control.

The docking studies indicate that compounds 2B and 3B are the most potent analogues as compared to standard acarbose (−5.5322 Kcal mol–1). The lowest binding energy of compound 2B was −9.5322 Kcal mol–1; thus, it was found to be a special inhibitor versus targeted biological protein 3AJ7. Compound 2B forms π–π interactions with important active side residue Tyr72 inside the active site of targeted protein 3AJ7. The compound 3B with a docking score of −8.8329 Kcal mol–1 portrays its inhibitory potential for the protein 3AJ7. The compound 3B showed that Lys156 was found in hydrogen bond interaction with the nitrogen of the thiazepine ring of 3B and further establishing a π-interaction with the methyl-substituted phenyl ring.

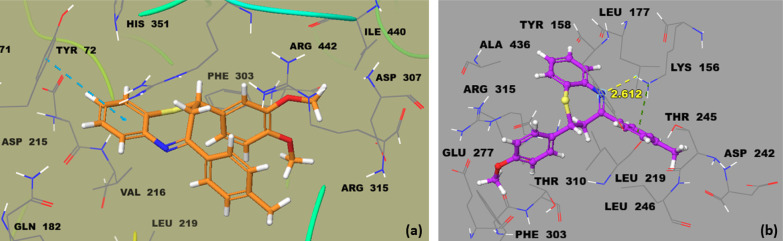

2.11. Molecular Docking Assay

The glide-dock module was implemented for the docking studies of selected ligands 2B and 3B against the crystal structure of the target protein α-glucosidase (PDB ID 3AJ7). The docking scores/energies were calculated (Table S1 in the SI), and docked complex images were also generated (Figure 7a,b). The predicted binding interactions by all docking processes suggested the docking scores (kcal/mol) in the range of −6.2681 to −9.5322, representing moderate to excellent interactions. Good inhibition of compounds 2B and 3B exhibit high occupancy of the inside surface grooves pointing to the best blocking of active-site amino acids.

Figure 7.

Binding interactions of compounds (a) 2B and (b) 3B in the active site of α-glucosidase.

The in silico molecular docking simulation and in vitro validation study revealed that compound 2B with an IC50 of 2.62 μM and docking score of −9.5322 is the most active among the current synthesized series. The compound 3B (IC50, 3.01 μM; docking score, – 8.8329) was observed as the second-ranked most active analogue in the α-glucosidase inhibitory assay. These compounds (2B and 3B) bind well in the active binding site of α-glucosidase. The crucial residues involved in inhibition and forming enzymatic binding pockets are Lys156, Glu277, Phe303, His351, and Arg315, as reported by Rahim et al.80 The phenyl ring of the most active compound 2B is predicted to form π–π interactions with important active side residue Tyr72 (Figure 7a). Lys156 was found in hydrogen bond interaction with the nitrogen of the thiazepine ring of 3B and further establishing a π-interaction with the methyl-substituted phenyl ring of 3B (Figure 7b).

2.12. QSAR Model

The cross-correlation between biological activity and chemical descriptors was assessed in this study to see if there was any common structure–activity relationship for the reported inhibitory impact against the crystal structure of α-glucosidase. It was revealed that the observed parameters had a high level of correlation with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.9553. As a result, the atomic models of benzothiazepines 1B–14B were created to elucidate potential QSARs for each molecule and their biological functions (Figure S55 in the SI). The atomic models of these benzothiazepines were created with hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction patterns in mind, as well as induced fit patterns that best represent each structure-binding interaction as assessed by logP values.92 The logP values were divided into training and test sets. As there is no previous data for the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of 1B–14B, the IC50 values were used for both the training set and the test set. The values of the test set were nearly identical to those of the training set (Figure S55 in the SI), indicating a positive association between logP values and biological activities. To accomplish a three-dimensional-QSAR, the MLR experiment was carried out. It could be concluded that biological activity might be improved if the phenyl ring is substituted by electron-donating substituents. The model quality was assessed using the cross-verified coefficient q.2 The external predictivity was calculated using the R2 correlation coefficient. The parameters employed in the QSAR model, as well as the obtained logP correlation coefficients, are listed below.

Activity field = logP (o/w); descriptor = SlogP; PLS = RMSE = 0.632029; R2 = 0.9999.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we have synthesized an interesting series of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines in moderate to excellent yields and characterized by spectral studies. Subsequently, the target compounds 1B–14B were evaluated for in vitro activity against α-glucosidase and in vivo antidiabetic activities. To explore the activity of synthesized 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines in terms of potential α-glucosidase inhibitors, we herein report an in vivo anti-hyperglycemic effect of the target compounds. All the final compounds 1B–14B exhibited α-glucosidase inhibitory potency with IC50 values ranging from IC50 = 2.62 ± 0.16 to 10.11 ± 0.32 μM as compared to standard acarbose (IC50 = 37.38 ± 1.37 μM). Compounds 2B and 3B showed potency with IC50 values of 2.62 ± 0.30 and 3.01 ± 0.29 μM, respectively, as compared to standard acarbose. In vivo anti-hyperglycemic activity was determined from the seven selected compounds based on higher α-glucosidase inhibitory values. The antidiabetic potential of compounds 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, and 12B–14B were further confirmed in the STZ-induced diabetic rat model. It is noteworthy that these compounds displayed a moderate to excellent anti-diabetic effect. The structure–activity relationships of synthesized target compounds were established. SAR indicated that compounds with electron-donating groups on the phenyl ring of 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine displayed pronounced anti-diabetic effects as compared to compounds with electron-withdrawing groups. Enzyme kinetics study of the most potent compounds, i.e., 2B and 3B, revealed its mode of inhibition as a competitive type. Molecular docking results agreed with in vitro biological assay data. From the QSAR model, it is concluded that biological activity might be improved if the phenyl ring (ring B) is substituted by electron-donating substituents. The 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines synthesized in this study seem to have the potential to become valuable lead molecules in designing new compounds with potential anti-diabetic activity.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials and Methods

All of the starting materials, solvents, and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Merck and were utilized as received. An electrothermal digital instrument was used to measure the melting points, which are uncorrected. A Nicolet FT-IR Impact 400D infrared spectrometer was used for recording the IR spectra of the solid samples by the matrix of KBr in the range of 400–4000 cm–1. NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker spectrometer (1H, 600 MHz; 13C, 151 MHz). NMR chemical shift values were defined in δ (ppm) units. TLC was used to monitor the reaction progress and completion, and spots were visualized under a UV lamp (254 nm). The QUARTZ cell was used to record the absorption spectra in CH3CN on a Jasco UV–vis V-660 spectrophotometer in a 200 to 800 nm wavelength range. Accurate mass measurements were carried out in the positive ion mode with a Fisons VG sector-field instrument (EI) and a FT-ICR mass spectrometer.

4.2. General Procedures for the Preparation of Chalcones681C–14C and Benzothiazepines791B–14B

In step 1, a mixture of substituted ketone (p-methylacetophenone; 1.0 mmol) and aryl aldehyde (1.0 mmol) were mixed in ethanol (20.0 mL) and stirred for 30 min at room temperature followed by the dropwise addition of an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (3.0 mL, 30%). Consequently, the reaction mixture was vigorously stirred at 25 °C for 2–3 h. The progress of the p-methylchalcone formation was examined by TLC using n-hexane:ethyl acetate (3:1) as a mobile phase. After reaction completion indicated by TLC, the reaction mass was kept at 0–4 °C overnight. Subsequently, it was cooled and neutralized with diluted HCl (10%) solution and poured onto the ice-cold water. The obtained precipitates were filtered, washed with water, and recrystallized from aqueous EtOH to obtain the purified compounds 1C–14C. In step 2, to a stirred solution of chalcone (1.0 mmol) in hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP; 10.0 mL) at ambient temperature, 2-aminobenzenethiol (2.0 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was heated to reflux for 3–4 h until a crystalline solid is obtained. After cooling, the precipitated solid was collected, washed with diethyl ether and cold methanol, and recrystallized from aqueous ethanol to afford the pure benzothiazepine products 1B–14B.

The spectroscopic data of already-reported compounds 1C–3C, 6C–8C, 10C, 11C, 13C, and 14C(81−88) and 1B–3B, 10B, 11B(68,89−91) are given in the literature. However, the spectral data of all the newly synthesized intermediate chalcones and 2,3-dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepines are given below.

4.2.1. 3-(4-(Hexyloxy)-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(p-tolyl)prop-2-en-1-one (4C)

Bright-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 85%; M.P. 150–152 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.85; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 264, 375 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3076, 1656, 1570, 1441, 1347, 1225, 1117, 1028, 846, 766; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.82 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.70 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.53 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.39 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.36 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.01 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.01 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, -OMe), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.74–1.70 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.43–1.39 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.32–1.29 (m, 4H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.90 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 189.0, 151.1, 149.6, 144.6, 143.7, 138.6, 135.7, 129.7, 129.0, 127.8, 124.3, 120.0, 117.2, 113.0, 111.4, 68.6, 56.2, 31.4, 29.0, 25.6, 22.5, 21.6, 14.3; accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C23H28O3, 352.2038; found, 352.2025.

4.2.2. 3-(3-Methoxy-4-propoxyphenyl)-1-(p-tolyl)prop-2-en-1-one (5C)

Off-white powder; yield: 88%; M.P. 123–125 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.8; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 254, 347 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3060, 2960, 1651, 1573, 1462, 1135, 1208, 1167, 1030, 716; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.08 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.82 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.71 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.54 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.38–7.35 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.01 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.98 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH3), 3.87 (s, 3H, -OMe), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.78–1.72 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH3), 0.98 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 189.0, 151.1, 149.6, 144.6, 143.7, 135.8, 129.7, 129.0, 128.0, 124.3, 120.0, 113.0, 111.4, 70.1, 56.2, 22.5, 21.6, 10.8 (remaining carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C20H22O3, 310.1569; found, 310.1560.

4.2.3. 3-(4-Butoxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(p-tolyl)prop-2-en-1-one (9C)

Light-yellow powder; yield: 76%; M.P. 178–180 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.9; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 279, 374 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 2974, 1647, 1584, 1473, 1313, 1259, 1173, 1030, 867, 740; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.81 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.70 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.55 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.53 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.39 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.36 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.01 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.01 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, -OMe), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.74–1.70 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.44–1.39 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.89 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 188.9, 151.1, 149.6, 144.6, 143.7, 138.9, 135.7, 129.7, 129.0, 127.8, 124.3, 119.9, 118.3, 112.9, 111.4, 68.6, 56.2, 31.4, 29.0, 21.6, 14.3; accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: Calcd. for C21H24O3 324.1725; found 324.1711.

4.2.4. 3-(4-(Benzyloxy)-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(p-tolyl)prop-2 -en-1-one (12C)

Off-white powder; yield: 78%; M.P. 138–140 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.6; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 259, 390 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 2915, 1654, 1587, 1447, 1317, 1286, 1217, 1015, 838, 736; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.08 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.99–7.96 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.92 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.75 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.39 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.32–7.29 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 5.20 (s, 1H, -CH2-), 5.12 (s, 1H, -CH2-), 3.85 (s, 3H, OMe), 2.40 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 189.0, 164.6, 163.0, 144.0, 142.8, 135.4, 131.9, 131.8, 131.7, 131.6, 129.8, 129.1, 128.7, 128.1, 127.8, 127.0, 125.6, 122.4, 122.2, 116.4, 116.1, 56.5, 55.6, 21.66; accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C24H22O3, 358.1570; found, 358.1562.

4.2.5. 2-(4-(Hexyloxy)-3-methoxyphenyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepine (4B)

Light-yellow solid; yield: 81%; M.P. 103–105 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.9; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 246, 362 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3031, 3005, 2918, 2836, 1648, 1554, 1463, 1314, 1208, 684; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.06 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.53 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.52–7.47 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.40 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.36 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.01 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.97 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, -OMe), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.74–1.70 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.43–1.40 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.33–1.29 (m, 4H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.89 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 167.9, 151.5, 144.0, 143.2, 137.3, 132.8, 130.4, 130.0, 129.7, 129.0, 128.7, 128.4, 127.8, 125.4, 124.3, 119.9, 116.5, 112.9, 111.4, 68.6, 60.2, 56.2, 37.5, 31.4, 29.1, 25.5, 22.6, 21.5, 14.3; accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C29H33NO2S, 459.2232; found, 459.2223.

4.2.6. 2-(3-Methoxy-4-propoxyphenyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepine (5B)

Light-yellow powder; yield: 78%; M.P. 116–118 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.7; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 281, 386 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3357, 2500, 1651, 1599, 1462, 1374, 1257, 1196, 689; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.54 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.53–7.48 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.37–7.33 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.01 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 5.01 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.96 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH3), 3.87 (s, 3H, -OMe), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.05 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.76–1.71 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH3), 0.98 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 168.4, 151.1, 149.6, 143.7, 135.8, 129.7, 129.5, 129.0, 128.1, 127.9, 127.4, 124.3, 112.9, 112.6, 113.1, 111.5, 70.1, 60.6, 56.2, 37.7, 22.4, 21.6, 10.8 (all the remaining carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C26H27NO2S, 417.1763; found, 417.1760.

4.2.7. 1-Phenyl-3-(4-(4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepin-2-yl)phenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (6B)

Yellow powder; yield: 78%; M.P. 146–148 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.5; UV–Vis λmax (CH3CN) = 249, 330 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3025, 2914, 2521, 1654, 1511, 1434, 1332, 1275, 1181, 680; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.06 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.82 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.79 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, -CO-CH=CH-), 7.75–7.70 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.65–7.60 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.55–7.46 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.42 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.35–7.28 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 4.97 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.05 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 188.9, 167.9, 164.7, 163.0, 156.6, 145.8, 134.8, 134.7, 131.6, 131.0, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 126.7, 117.0, 116.9, 114.7, 60.4, 37.5, 10.8 (remaining all carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C31H25NOS, 459.1657; found, 459.1660.

4.2.8. 4-(4-(p-Tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepin-2-yl)benzoic acid (7B)

Light-yellow crystals; yield: 89%; M.P. 225–227 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.4; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 260, 329 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3006, 2887, 2791, 2573, 1672, 1555, 1468, 1334, 1229, 673; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.74 (s, 1H, -COOH), 8.08 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.83 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.80–7.54 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.38 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 5.01 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.17 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.09 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 176.5, 167.9, 164.7, 163.0, 156.6, 145.8, 134.8, 134.7, 131.6, 131.0, 128.4, 128.3, 128.1, 116.9, 114.7, 60.4, 37.5, 10.8 (remaining all carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C23H19NO2S, 373.1137; found, 373.1144.

4.2.9. 2-(4-Ethoxyphenyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepine (8B)

Light yellow powder; yield: 78%; M.P. 106–108 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.5; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 257, 359 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3051, 2916, 2848, 1675, 1557, 1463, 1318, 1237, 1137, 688; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.05 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.56 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.52–7.46 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.38–7.34 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.00 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.10 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.95 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, -OMe), 3.36 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.07 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.40 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.75–1.70 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH3), 1.33 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 168.0, 161.0, 144.1, 143.7, 135.7, 131.2, 130.5, 130.4, 129.7, 128.4, 127.6, 125.1, 119.8, 117.2, 115.2, 111.6, 63.8, 60.5, 56.0, 37.4, 21.6, 15.0 (all remaining carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C24H23NOS, 373.1500; found, 373.1484.

4.2.10. 2-(4-Butoxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepine (9B)

Off-white powder; yield: 81%; M.P. 120–122 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.8; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 259, 373 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 2983, 2922, 2597, 1648, 1563, 1453, 1340, 1219, 1175, 676; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.06 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.67 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.53 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.52–7.36 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.39 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.35 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.99 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, -OMe), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.05 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.41 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.73–1.70 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.43–1.29 (m, 2H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.88 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H, -OCH2CH2CH2CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 167.9, 151.1, 149.6, 144.6, 143.7, 135.7129.7, 129.0, 127.8, 124.3, 119.9, 112.9, 111.4, 68.6, 60.4, 56.2, 37.5, 31.4, 29.0, 21.6, 14.3 (remaining all carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C27H29NO2S, 431.1919; found, 431.1925.

4.2.11. 2-(4-(Benzyloxy)-3-methoxyphenyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepine (12B)

Light-yellow powder; yield: 87%; M.P. 126–128 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.6; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 244, 351 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3050, 1885, 1677, 1565, 1448, 1319, 1221, 1156, 1014, 652; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.90–7.84 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.98–7.39 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.38 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.37–7.29 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 5.24 (s, 1H, -CH2-), 5.10 (s, 1H, -CH2-), 5.16 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.84 (s, 3H, OMe), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 1.28 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 167.9, 164.6, 163.0, 144.0, 142.8, 135.4, 131.9, 131.8, 131.7, 131.6, 129.8, 129.1, 128.9, 128.5, 128.4, 127.3, 126.3, 122.4, 122.3, 116.5, 116.4, 116.3, 51.6, 40.2, 21.6, 15.0 (all remaining carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C30H27NO2S, 465.1763; found, 465.1744.

4.2.12. 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepine (13B)

Light-yellow powder; yield: 76%; M.P. 111–113 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.9; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 268, 349 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3025, 2915, 2847, 1653, 1588, 1418, 1332, 1206, 1014, 623; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.08 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.83 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.71–7.54 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.38 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 5.01 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.17 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 2.09 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 167.9, 164.7, 163.0, 156.6, 145.8, 145.7, 134.8, 134.7, 131.6, 131.0, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 126.7, 117.0, 116.9, 114.7, 60.4, 37.5, 14.3 (all remaining carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C22H18FNS, 347.1144; found, 347.1131.

4.2.13. N,N-Dimethyl-4-(4-(p-tolyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,5]thiazepin-2-yl)aniline (14B)

Light-maroon powder, yield: 87%; M.P. 193–195 °C; Rf (n-hexane: ethyl acetate; 3:1) = 0.5; UV–vis λmax (CH3CN) = 263, 336 nm; FTIR (cm–1): 3396, 3046, 2894, 2648, 1613, 1548, 1456, 1330, 1233, 689; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07–7.82 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.79–7.67 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.53 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.52–7.36 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.35 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 4.99 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H-C-H), 3.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, -CH), 3.05 (s, 3H, -N(CH3)3), 3.01 (s, 3H, -N(CH2)3), 2.92 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 167.9, 164.7, 163.0, 156.6, 145.8, 134.8, 134.7, 131.6, 131.0, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 126.7, 117.0, 116.9, 114.7, 60.4, 37.5, 28.8, 14.3 (remaining all carbons are isochronous); accurate mass (EI-MS) of [M]+·: calcd. for C24H24N2S, 372.1660; found, 372.1652.

4.3. Enzyme Inhibition Activity

4.3.1. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

The derivatives 1B–14B were tested against α-glucosidase. The test samples were prepared in varying concentrations by mixing 20 μL of α-glucosidase (0.5 units/mL), 120 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) and 10 μL of 1B–14B. For incubation of the mixture solutions, 96-well plates were used at 37 °C for 15 min. To initiate the enzymatic reaction, 20 μL of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) was added to the mixture and reincubated for another 15 min. Sodium carbonate (80 μL, 0.2 M) was added to prevent the reaction, and then absorbance was taken at 405 nm using a microplate reader. For positive control, a sample-free reaction system was used, and the blank was without α-glucosidase for the purpose of background absorbance correction.1,92

4.3.2. Animals

Male Wistar albino rats (170–200 g) and Balb/C mice (19–23 g) aged 8–10 weeks old were procured from the the Veterinary Research Institute (VRI), Lahore, and kept at an animal house in standard plastic cages under standard laboratory conditions with 25 ± 2 °C temperature, relative humidity of 55–65%, and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with standard diet and water ad libitum. Before 2 weeks of the experiment, the animals were adapted to laboratory conditions. The animals were treated following the principles mentioned in the “Animal Bylaws 2008 of University of Malakand (Scientific Procedures Issue I)”. Approval for the study was granted by the Ethical Committee of the Department of Pharmacy, in accordance with the Animal Bylaws 2008 of University of Malakand, vide notification no. Pharm/EC-Thzp/41-08/21.

4.3.3. Acute Toxicity Study

For the determination of the acute toxicity of 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B samples, the weight of the mice was kept in the range of 20–25 g. Animals were distributed in groups having four animals each. The reported protocols by Lorke93 were followed with slight modifications to perform a test in two phases. In the first phase, one group (control group) of animals was given Tween-80 (2%) and oral doses of the 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, and 12B–14B were given to the remaining groups at 100, 500, and 1000 mg/kg body weight. During the second phase, the respective oral doses of both extracts was given at 1250, 1500, and 2000 mg/kg body weight. Animals were checked initially for 24 h and on a daily basis for observing signs of diarrhea, convulsions, lethargy, sleeping, salivation, and tremors for 2 weeks. The animals were also monitored for mortality when possible and housed in plastic cages.

Selection of doses (2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 mg/kg b.w.) for in vivo pharmacological assessment (antidiabetic activity) using an animal model was carried out from in vivo toxicological studies as per OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) (2001) guidelines, the approach to practical acute toxicity testing by Dietrich Lorke (1983), and Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. Effective doses (mg/kg b.w.) were selected for behavioral studies after preliminary pharmacological assessment in our laboratory as well as published data elsewhere. The findings of preliminary pharmacological activity lent a hand to standardize 1B–14B for the assessment and selection of doses for pharmacological investigation.

4.3.4. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B was performed in overnight fasted normal rats that were divided into different groups (n = 8). Group 1 was administered 2% (w/v) Tween-80, group 2 received glibenclamide, and the remaining groups received the respective doses of tested compounds. At 30 min after the administration, glucose (3 g/kg) was fed. Blood glucose level was estimated at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min of glucose administration using an SD glucometer (ACCU-CHECK, Active blood glucose meter, Korea).

4.3.5. Induction of Diabetes

After acclimatization, intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) of streptozotocin (50 mg/kg, 0.1 M citrate buffer) was administered to overnight fasted rats. In addition, to avoid the death of the animals due to streptozotocin-induced hypoglycemic shock, the rats were subsequently given 10% glucose solution for 3 days. After 72 h, the levels of blood glucose from the tail vein were measured using touch glucometer strips and an SD glucometer (ACCU-CHECK Active Blood Glucose Meter, Korea). For further study, fasting blood glucose levels greater than 250 mg/dL were considered diabetic.94

4.3.6. Experimental Design for Antidiabetic Activity

The animals were divided randomly into experimental groups (n = 8) consisting of normal control, diabetic control, and diabetic treated with 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w. of 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B as well as a glibenclamide positive control group (500 μg/kg, p.o.). The animals in control (normal) and STZ diabetic rat groups were administered with vehicle only. Treatment with 2B, 3B, 6B, 7B, 12B, 13B, and 14B p.o. was kept continued with crude extract and fractions once daily for 4 weeks (28 days). Body weight and blood glucose levels were taken on the 1st, 7th, 14th, 21st, and 28th day of treatment.95

4.3.7. Estimation of the Serum Profile

Upon antidiabetic assay completion on the 28th day, pentobarbital sodium (35 mg/kg) was given to anesthetize all the animals for the collection of blood samples through cardiac puncture to assess biochemical parameters including serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides (TGs), total cholesterol (TC), serum creatinine, and insulin levels.96

4.3.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Analysis of variance and Dunnett’s comparison is statistically manipulated with GraphPad Prism software version 5.01.

4.4. Kinetic Studies

The mode of inhibition of the most active compounds 2B and 3B identified with the lowest IC50 was investigated against α-glucosidase activity with different concentrations of p-nitrophenyl α-d-glucopyranoside (2–10 mM) as substrate in the absence and presence of samples 2B and 3B at different concentrations (0, 30, 50, and 70 μM). A Lineweaver–Burk plot was generated to identify the type of inhibition, and the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) value was determined from the plot between the reciprocal of the substrate concentration (1/[S]) and reciprocal of enzyme rate (1/V) over various inhibitor concentrations. The inhibition constant (Ki) value was constructed by secondary plots of the inhibitor concentration [I] versus Km.97

4.5. Molecular Docking Study

Due to the absence of a high-resolution crystal structure of the human enzyme and the fact that both proteins share high sequence similarity in their active core region, Saccharomyces cerevisiae has frequently served as a model to assess the inhibitory activity of compounds. However, only a very small number of homology models have been reported;98−100 thus, we used a comparative homology modeling approach to construct a 3D model for α-glucosidase using the same protocol as described by Taha et al.101 MOE search tools were used to find templates in the Protein Data Bank, which was incorporated into MOE (v2015.10). The template for modeling was chosen from the crystallographic structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae isomaltase (PDB ID 3AJ7),102 which shows sequence similarity with the target. MOE homology modeling methods were used to construct their 3D structure. Energy minimization was applied to the resulting 3D model up to 0.05 gradients. MOE was utilized to prepare all the ligands and proteins before docking. Finally, a database was developed where ligands were turned into 3D structures, and this database file was utilized as the MOE docking input file by applying the Amber 10: EHT force field to reduce the energy up to 0.01 gradient. The protonation of proteins was performed by protonate 3D tool before starting the ligand docking. Using the Triangular Matcher approach and 30 conformations, the database was docked into the active site of the target protein, each with a docking score (S). Interactions of each complex were examined, and the 3D images were produced using Maestro Schrodinger (v2017–2).103

4.6. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Studies

The Canvas (v3.2) tool in the Maestro Schrodinger suite created a quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) report to identify common scaffolds in benzothiazepine structures utilized in this investigation. All the docked molecules were used as a training set, whereas the QSAR model correlates the activities with the inherent properties of each molecule in a test set. Various molecular descriptors were employed to determine these properties. Two stages are involved in QSAR research. Descriptors were created in the first phase to encode chemical structural information. A multiple linear regression (MLR) approach is employed in the second step to relate structural variation, as evaluated by descriptors, to variance in protein biological activity. Regression analysis was used to assess the findings’ dependability, employing inhibition activity as a dependent variable and description as a predictor factor. After confirming a good link of inhibitory activity with each unique description, QSAR models with p < 0.05 were generated to assure statistical reliability.103,104

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R95), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University for supporting this work under grant code 22UQU4320545DSR23. The financial support by the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) under project no. NRPU-15800 is also gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- LDL

low-density lipoproteins

- MOE

molecular operating environment

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- QSAR

quantitative structure–activity relationship

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TC

total cholesterol

- TGs

triglycerides

- VRI

veterinary research institute

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c03328.

FTIR spectra of newly synthesized compounds, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of newly synthesized compounds, docking images of all the target compounds, table of docking energy values, and QSAR images of the representative compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

R.M. was in charge of data analysis and collection. E.U.M. was in charge of the main idea, supervision, and final writing of the manuscript. E.B.E. was in charge of biological analysis and reviewing. R.J.O. was in charge of data analysis and collection. Y.N. performed molecular docking and QSAR studies. H.A.A.-G. was in charge of biological analysis and reviewing. N.N. was in charge of experimental work performance, data analysis and collection, and first draft preparation. M.M.A.-R. was in charge of formal analysis. S.A.A. was in charge of formal analysis. A.S. was in charge of the main idea, supervision, and final writing of the manuscript. S.W.A.H. performed in vitro and in vivo studies.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ashraf J.; Mughal E. U.; Sadiq A.; Naeem N.; Muhammad S. A.; Qousain T.; Zafar M. N.; Khan B. A.; Anees M. Design and synthesis of new flavonols as dual α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors: structure-activity relationship, drug-likeness, in vitro and in silico studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1218, 128458–128467. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji A. S.; Suhas B. J.; Ashok M. A.; Mangesh T. Serum alanine transaminases and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes mellitus Indian patients. J. Diabetes Res. 2013, 2013, 613176. 10.5171/2013.613176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazeem M. I.; Adamson J. O.; Ogunwande I. A. Modes of inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase by aqueous extract of Morinda lucida Benth leaf. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 527570 10.1155/2013/527570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H. J.; Kim J.-S.; Hyun T. K.; Yang J.; Kang H.-H.; Cho J.-C.; Yeom H.-M.; Kim M. J. In vitro antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of Rehmannia glutinosa tuberous root extracts. ScienceAsia 2013, 39, 605–609. 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2013.39.605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naim M. J.; Alam M. J.; Nawaz F.; Naidu V.; Aaghaz S.; Sahu M.; Siddiqui N.; Alam O. Synthesis, molecular docking and anti-diabetic evaluation of 2, 4-thiazolidinedione based amide derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 73, 24–36. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani R.; Pathak D. P.; Kapoor G.; Husain A.; Iqbal M. A. Novel hybrids of benzothiazole-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole-4-thiazolidinone: Synthesis, in silico ADME study, molecular docking and in vivo anti-diabetic assessment. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 83, 6–19. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond R. M.; McLane M. P.; Law W. R.; King N. F.; Leutz D. W. Myocardial insulin resistance during acute endotoxin shock in dogs. Diabetes 1988, 37, 1684–1688. 10.2337/diab.37.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Peñalver J. J.; Martín-Timón I.; Sevillano-Collantes C.; del Cañizo-Gómez F. J. Update on the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2016, 7, 354–362. 10.4239/wjd.v7.i17.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi S.; Toolabi M.; Salarinejad S.; Firoozpour L.; Ebrahimi S. E. S.; Safari F.; Mojtabavi S.; Faramarzi M. A.; Foroumadi A. Design and synthesis of novel pyridazine N-aryl acetamides: In-vitro evaluation of α-glucosidase inhibition, docking, and kinetic studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 102, 104071 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S.; Saraf S. Type 2 diabetes mellitus—Its global prevalence and therapeutic strategies. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2010, 4, 48–56. 10.1016/j.dsx.2008.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taha M.; Ismail N. H.; Imran S.; Wadood A.; Ali M.; Rahim F.; Khan A. A.; Riaz M. Novel thiosemicarbazide–oxadiazole hybrids as unprecedented inhibitors of yeast α-glucosidase and in silico binding analysis. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 33733–33742. 10.1039/C5RA28012E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salar U.; Taha M.; Khan K. M.; Ismail N. H.; Imran S.; Perveen S.; Gul S.; Wadood A. Syntheses of new 3-thiazolyl coumarin derivatives, in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, and molecular modeling studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 122, 196–204. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Huang Y.-N.; Xu P.-Y.; Kawabata J. Inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase by the fruits of Terminalia chebula Retz. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 628–634. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi F.; Azizian H.; Najafi M.; Hassanzadeh F.; Sadeghi-Aliabadi H.; Ghasemi J. B.; Faramarzi M. A.; Mojtabavi S.; Larijani B.; Saghaei L. Design and synthesis of novel quinazolinone-pyrazole derivatives as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors: Structure-activity relationship, molecular modeling and kinetic study. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 114, 105127 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff H. Effect of acarbose on diabetic late complications and risk factors–new animal experimental results. Akt. Endokr. Stoffw. 1991, 12, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeier U.; Piepersberg W. Biotechnology and molecular biology of the α-glucosidase inhibitor acarbose. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 63, 613–625. 10.1007/s00253-003-1477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh A. J.; Yao S.; Young J. D.; Cheeseman C. I. Inhibition of glucose absorption in the rat jejunum: a novel action of alpha-D-glucosidase inhibitors. Gastroenterology 1997, 113, 205–211. 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Laar F. A. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors in the early treatment of type 2 diabetes. Vasc. Health Risk Manage. 2008, 4, 1189–1195. 10.2147/VHRM.S3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripsin C. M.; Kang H.; Urban R. J. Management of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. Fam. Physician 2009, 79, 29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde J.; Taldone T.; Barletta M.; Kunaparaju N.; Hu B.; Kumar S.; Placido J.; Zito S. W. α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of Syzygium cumini (Linn.) Skeels seed kernel in vitro and in Goto–Kakizaki (GK) rats. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343, 1278–1281. 10.1016/j.carres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen A. J. Is there a role for α-glucosidase inhibitors in the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus?. Drugs 2003, 63, 933–951. 10.2165/00003495-200363100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M.; Kaushal R. Synthesis and in-silico molecular modelling, DFT studies, antiradical and antihyperglycemic activity of novel vanadyl complexes based on chalcone derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1252, 132176–132184. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhameja M.; Gupta P. Synthetic heterocyclic candidates as promising α-glucosidase inhibitors: An overview. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 176, 343–377. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrington M. S.; Davis S. N. Considerations when using alpha-glucosidase inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 20, 2229–2235. 10.1080/14656566.2019.1672660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.-T.; Deng X.-Y.; Chen J.; Liang Q.-M.; Zhang K.; Li D.-L.; Wu P.-P.; Zheng X.; Zhou R.-P.; Jiang Z.-Y.; Ma A. J.; Chen W. H.; Wang S. H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of coumarin derivatives as α-glucosidase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 189, 112013–112020. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.112013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usman B.; Sharma N.; Satija S.; Mehta M.; Vyas M.; Khatik G. L.; Khurana N.; Hansbro P. M.; Williams K.; Dua K. Recent developments in alpha-glucosidase inhibitors for management of type-2 diabetes: An update. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 2510–2525. 10.2174/1381612825666190717104547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed S.; Seraj F.; Rafique R.; Chigurupati S.; Wadood A.; Rehman A. U.; Venugopal V.; Salar U.; Taha M.; Khan K. M. Synthesis of benzotriazoles derivatives and their dual potential as α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors in vitro: Structure-activity relationship, molecular docking, and kinetic studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111677–111772. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummidi L.; Kerru N.; Ebenezer O.; Awolade P.; Sanni O.; Islam M. S.; Singh P. Multicomponent reaction for the synthesis of new 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole-thiazolidine-4-one molecular hybrids as promising antidiabetic agents through α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 115, 105210–105222. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]