Abstract

Reporter gene fusions were used to investigate the contributions of PrfA DNA binding sites to Listeria monocytogenes virulence gene expression. Our results suggest that the DNA sequence of PrfA binding sites determines the levels of expression of certain virulence genes, such as hly and mpl. Other virulence genes, such as actA and plcB, may depend upon additional factors for full regulation of gene expression.

Listeria monocytogenes is a ubiquitous, gram-positive bacterial pathogen that can cause relatively rare but serious infections in immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women (11, 29). The bacterium is a facultative intracellular parasite that invades a wide variety of cell types and is capable of escaping from membrane-bound phagosomes or endosomes to replicate within the host cell cytosol (24, 35). Subsequent to bacterial replication, L. monocytogenes can spread directly into adjacent cells by a motility mechanism based on host cell actin polymerization (5, 8, 17, 24, 28, 34, 35).

Several gene products important for L. monocytogenes intracellular growth and/or cell-to-cell spread have been identified. hly encodes listeriolysin O, a pore-forming hemolysin required for efficient escape of the bacterium from host cell vacuoles; plcA encodes a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) that aids in vacuolar escape; plcB encodes a broad-specificity phospholipase C (PC-PLC) that is important for cell-to-cell spread; mpl encodes a metalloprotease that processes proPC-PLC to its active form; and actA encodes a membrane protein essential for bacterial actin-based motility (reviewed in references 4, 13, 25, 32, and 33). The expression of each of these genes is regulated by a transcriptional activator protein known as PrfA (21, 22). The prfA gene product is a key regulatory component of L. monocytogenes pathogenesis; bacterial strains that lack functional PrfA protein are avirulent in mouse models of infection (9, 21, 22, 30).

PrfA is a 27-kDa protein with significant homology to members of the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP)-FNR family of pleiotropic transcription regulators (19, 20, 32). It recognizes and binds to a 14-bp DNA palindromic sequence that is present in the −40 region of target gene promoters (1, 6, 9, 31). Certain PrfA-regulated promoters contain PrfA DNA binding sites that are imperfect palindromes, and it has been postulated that PrfA binds with a lower affinity to imperfect promoter palindromes (such as those present upstream of mpl and actA) than to perfect ones (hly and plcA) (9). In support of this hypothesis, it has been recently demonstrated, using in vitro DNA footprinting studies, that PrfA binds to the hly/plcA promoter with a higher affinity than to the inlA promoter (6). Specific nucleotide substitutions within the PrfA binding site have also been shown to abolish PrfA-dependent activation of gene expression (10).

Expression of PrfA-dependent gene products is differentially regulated. Certain gene products, such as those encoded by hly or plcA, are expressed at significant levels by bacteria grown in rich broth culture, whereas other PrfA-regulated gene products, such as mpl and actA, are expressed at small to undetectable amounts under standard broth culture conditions (23). Upon entry of L. monocytogenes into the environment of the host cell cytosol, hly expression increases approximately 20-fold, whereas actA expression increases over 226-fold and ActA becomes one of the most abundant surface proteins expressed (2, 3, 23). A model has been proposed to describe the ability of PrfA to differentially regulate gene expression in an environment-dependent manner (9). Outside of host cells or at the onset of infection, PrfA is present within the bacterial cell at low to moderate levels and binds and activates transcription from promoters with high-affinity PrfA binding sites (such as hly and plcA). Upon entry into the cytosol, PrfA protein synthesis increases to provide sufficient levels of PrfA to occupy low-affinity promoter sites (such as those upstream of mpl and actA). Recent evidence suggests that PrfA may also require posttranslational modification or interaction with additional factors for full activity, and a revised model incorporating these observations has been proposed (36).

A central premise of the PrfA regulatory models is that the affinity of PrfA for its target promoter sites determines the levels and timing of gene expression. We wished to determine if the sequence variations present in the PrfA binding sites of different target promoters were sufficient to account for the levels of gene expression observed under extracellular growth conditions.

Use of a B. subtilis-based expression system to monitor PrfA-dependent gene expression.

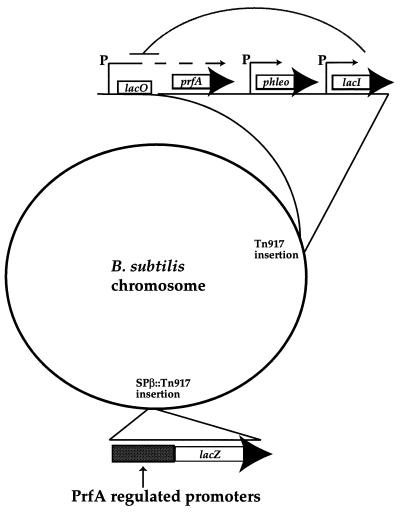

Previous experiments using B. subtilis-based expression systems have demonstrated that PrfA protein is capable of activating transcription from target promoters in the absence of any additional L. monocytogenes factors (10, 30). Activation of expression from certain promoters, namely actA and mpl, was considerably weaker and occurred more slowly than that observed for the hly and plcA promoters, suggesting that greater quantities of PrfA were required for productive interaction (30). We used the Bacillus subtilis-based expression system referred to above (10) to measure the ability of PrfA to activate expression from target promoters containing specific nucleotide substitutions in the PrfA binding sites (Fig. 1). The relevant B. subtilis strains are shown in Table 1. Mutations within the hly, mpl, and actA promoters were generated by PCR (12) with the primers described in Table 2, and the products were cloned upstream of a promoterless copy of lacZ (14). The mutant promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions were then transduced with SPβ phage (15) into the chromosome of B. subtilis strains that contained an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible chromosomal copy of prfA as previously described (10) (Fig. 1). PrfA-dependent activation of target promoter-lacZ fusions was monitored by measuring β-galactosidase activity following induction of prfA expression (10, 37).

FIG. 1.

Strategy for measuring the ability of PrfA to activate target promoters containing PrfA box nucleotide substitutions. Expression of prfA in B. subtilis was placed under the control of the IPTG-inducible promoter Pspac by insertion of a DNA fragment containing the prfA coding sequence into the SPAC expression cassette of pAG58-phleo (38). The expression cassette was then integrated by recombination at the site of a phenotypically silent Tn917 insertion (14). The activity of PrfA-dependent promoter constructs was monitored by using lacZ transcriptional fusions, which were integrated by recombination into SPβ prophages and then transduced into a specific site within the chromosome of B. subtilis strains containing Pspac-prfA (39).

TABLE 1.

Relevant bacterial strains used in this study

| Straina | Promoter | PCR primers used to construct promoter fusionb | PrfA DNA binding site sequencec |

|---|---|---|---|

| DP-B1451 | hly | Sau96-HindIII fragment | 5′ TTAACATTTGTTAA 3′ |

| NF-B380 | hly (T12→A) | hly-P4, hly-mpl1 | 5′ TTAACATTTGTAAA 3′ |

| NF-B438 | hly (T7→A, T8→A) | hly-P4, hly-mpl3 | 5′ TTAACAAATGTTAA 3′ |

| NF-B381 | hly (T7→A, T8→A, T12→A) | hly-P4, hly-mpl2 | 5′ TTAACAAATGTAAA 3′ |

| NF-B398 | mpl | mpl-C, mpl-N1 | 5′ TTAACAAATGTAAA 3′ |

| NF-B399 | mpl (A12→T) | mpl-C, mpl-N2 | 5′ TTAACAAATGTTAA 3′ |

| NF-B591 | mpl (A7→T, A8→T, A12→T) | mpl-C, mpl-N3 | 5′ TTAACATTTGTTAA 3′ |

| NF-B418 | actA | actA-C, actA-N1 | 5′ TTAACAAATGTTAG 3′ |

| NF-B419 | actA (G14→A) | actA-C, actA-N2 | 5′ TTAACAAATGTTAA 3′ |

| NF-B647 | actA (A7→T, A8→T, G14→A) | actA-C, actA:hlyP | 5′ TTAACATTTGTTAA 3′ |

TABLE 2.

Primers designed to amplify and introduce nucleotide substitutions into PrfA target promoter PCR products

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| hly-P4 | 5′-TTTGGATAAGCTTGAGCATATT-3′ |

| HindIII | |

| hly-mpl1 | 5′-ATGTGGATCCATTAACATTTGTAAATGA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| hly-mpl2 | 5′-ATGTGGATCCATTAACAAATGTAAATGA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| hly-mpl3 | 5′-ATGTGGATCCATTAACAAATGTTAATGA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| mpl-C | 5′-GGGCAAGCTTCACCGCTCCTTTTTAA-3′ |

| HindIII | |

| mpl-N1 | 5′-GCGGATCCGAATTAACAAATGTAA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| mpl-N2 | 5′-GCGGATCCGAATTAACAAATGTTAAAGAA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| mpl-N3 | 5′-GCGGATCCGAATTAACATTTGTTAAAGAA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| actA-C | 5′-GGGCAAGCTTATACTCCCTCCTCGT-3′ |

| HindIII | |

| actA-N1 | 5′-GCGGATCCTGATTAACAAATGTTAG-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| actA-N2 | 5′-GCGGATCCTGATTAACAAATGTTAAAGAAAA-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome | |

| actA:hlyP | 5′-GCGGATCCTGATTAACATTTGTTAAAGAAAAATT-3′ |

| BamHI Palindrome |

Substitution of the hly promoter palindrome with the mpl promoter palindrome reduces hly expression.

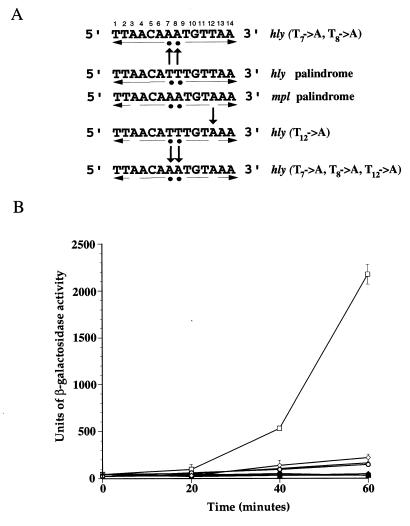

Previous work demonstrated that hly-lacZ fusions are efficiently expressed following induction of prfA in B. subtilis, whereas mpl-lacZ and actA-lacZ fusions are both poorly expressed in comparison and require longer periods of prfA induction (30). The mpl and actA promoter palindromes each have 3 base substitutions in comparison to the hly/plcA palindrome; to determine if these base differences were sufficient to account for the lower levels of transcriptional activation observed, specific nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the hly PrfA DNA binding site as shown in Fig. 2A, and their effect on PrfA-dependent activation of expression was determined. A single base substitution (T12→A), designed to make the hly palindrome more closely resemble that of mpl, was sufficient to lower expression levels of hly by 90% (Fig. 2B). Similar reductions in hly expression were observed for the hly(T7→A, T8→A) and hly(T7→A, T8→A, T12→A) promoter substitutions (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that the sequence composition of the PrfA DNA binding site is a major factor in determining levels of hly expression.

FIG. 2.

Effects of PrfA-box mutations on hly-lacZ expression. (A) Nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the hly promoter palindrome to increase its similarity to the mpl promoter palindrome. Substituted nucleotides are designated by arrows. (B) β-Galactosidase activity was measured at the indicated time intervals in cultures of B. subtilis strains containing the wild-type hly promoter or hly promoter substitution mutant-lacZ fusions and Pspac-prfA in the presence (open symbols) or absence (solid symbols) of IPTG. Units of β-galactosidase are as described by Youngman (37). Individual time points were done in duplicate, and the data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. □ and ■, hly palindrome; ○ and ●, hly(T12→A); ◊ and ⧫, hly(T7→A, T8→A); ▵ and ▴, hly(T7→A, T8→A, T12→A).

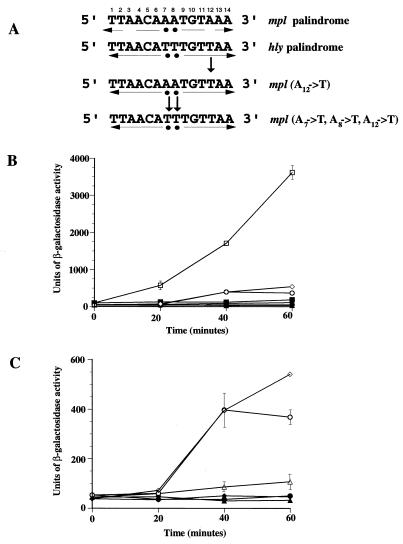

Substitution of the mpl promoter palindrome with the hly promoter palindrome increases mpl expression.

Because a single base substitution within the hly PrfA DNA binding site resulted in an hly expression pattern comparable to that obtained for mpl (compare Fig. 2B and 3B), we wanted to determine if the converse situation would also prove true; would specific nucleotide substitutions within the mpl palindrome, designed to increase its similarity to the hly palindrome, result in mpl expression levels that would be comparable to those of hly? mpl-lacZ expression normally exhibits an approximately threefold induction over background expression levels after 60 min of IPTG-mediated prfA expression (Fig. 3B and C). The introduction of a single base change (A12→T) increased mpl-lacZ induction 7-fold, and the mpl(A7→T, A8→T, A12→T) promoter substitution resulted in a 12-fold induction of β-galactosidase activity after 60 min (Fig. 3B and C). In comparison, hly-lacZ exhibited a 36-fold induction over background expression levels (Fig. 3B). Thus, nucleotide substitutions designed to make the mpl palindrome more “hly-like” resulted in significantly higher levels of mpl expression. The substitution for the mpl palindrome of the hly palindrome was, however, not sufficient to raise levels of mpl expression to those observed for hly, indicating that additional sequence outside of the 14-bp palindrome may also contribute to optimize activation.

FIG. 3.

Effects of PrfA box mutations on mpl-lacZ expression. (A) Nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the mpl promoter palindrome to increase its similarity to the hly promoter palindrome. Substituted nucleotides are designated by arrows. (B) β-Galactosidase activity was measured at the indicated time intervals in cultures of B. subtilis strains containing the wild-type mpl promoter or mpl promoter substitution mutant-lacZ fusions and Pspac-prfA in the presence (open symbols) or absence (solid symbols) of IPTG. Individual time points were examined in duplicate, and the data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. (C) Expanded view of the induction of β-galactosidase activity observed for the mpl promoter substitution mutants. □ and ■, hly palindrome; ▵ and ▴, mpl palindrome; ○ and ●, mpl(A12→T); ◊ and ⧫, mpl(A7→T, A8→T, A12→T).

Substitution of the actA promoter palindrome with the hly palindrome produces no effect on actA expression.

The actA promoter palindrome, like mpl, has several nucleotide substitutions within the PrfA binding site that distinguish it from the hly palindrome. To determine if actA expression levels could be increased by nucleotide substitutions within the promoter palindrome that were designed to make it more hly-like, two actA promoter-lacZ fusion constructs were generated [actA(G14→A) and actA(A7→T, A8→T, G14→A)] (Fig. 4A). However, and in contrast to what was observed for mpl, the introduction of a G14→A change or the triple base change (A7→T, A8→T, G14→A) into the actA promoter palindrome resulted in no increase in actA expression levels (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that altering the nucleotide composition of the actA promoter palindrome was not sufficient to increase PrfA-directed activation of expression.

FIG. 4.

Effects of PrfA-box mutations on actA-lacZ expression. (A) Nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the actA promoter palindrome to increase its similarity to the hly promoter palindrome. Substituted nucleotides are designated by arrows. (B) β-Galactosidase activity was measured at the indicated time intervals in cultures of B. subtilis strains containing the wild-type actA promoter or the actA promoter substitution mutant-lacZ fusions and Pspac-prfA in the presence (open symbols) or absence (solid symbols) of IPTG. Individual time points were examined in duplicate, and the data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. □ and ■, hly palindrome; ▵ and ▴, actA palindrome; ○ and ●, actA(G14→A); ◊ and ⧫, actA(A7→T, A8→T, G14→A).

Domann et al. (7) reported the presence of a putative transcriptional terminator downstream of mpl in the promoter region of actA. The 5′ end of the 64-bp stem-loop structure identified by Domann et al. (7) overlaps the site of actA transcript initiation, and it seemed plausible that the presence of such a stem-loop structure might influence or inhibit PrfA-directed activation of actA expression. An actA promoter-lacZ reporter gene construct was generated that contained the hly promoter palindrome and a deletion of the majority of the actA putative stem-loop structure, but retained the actA transcript initiation site (from +3 relative to the start site of transcription to +51—a deletion of 48 bp; the GTG translational start codon of actA is at position +150). This promoter fusion was introduced into the B. subtilis expression system, and β-galactosidase activity was measured as a function of PrfA-directed activation of actA expression. Deletion of the potential stem-loop structure did not result in increased actA expression (J. R. Williams and N. E. Freitag, unpublished data).

In summary, the experiments described in this study indicate that although the sequence composition of the PrfA DNA binding site is a major determinant of promoter activity in certain promoters, such as hly and mpl, other promoters, such as actA, may require additional factors or activation events for optimal expression. Our study did not assess the binding affinity of PrfA for different target promoters or the efficiency of transcriptional activation. Instead, we demonstrated that the substitution of the PrfA binding site from a highly expressed promoter (hly) for that of a poorly expressed promoter binding site (mpl or actA) was sufficient in the case of the mpl promoter to increase expression, but had no effect on the actA expression levels. DNA footprinting studies have identified an approximately 26-bp region, beginning 10 bp upstream of the 14-bp palindrome and ending 2 bp downstream, that is protected from DNase I digestion in the presence of PrfA protein (6). Based on these studies, it is likely that additional promoter sequences flanking the 14-bp palindrome contribute to PrfA binding and recognition. Nevertheless, it was surprising to see absolutely no affect on PrfA-dependent activation of actA expression following substitution of the 14-bp actA palindrome for that of hly. Our results suggest that there may exist additional events besides the binding of PrfA to the actA promoter that are involved in the regulation of actA expression.

The use of the B. subtilis assay system allows measurement of PrfA-dependent promoter activation in the absence of any additional L. monocytogenes factors. PrfA shares significant homology with the CRP-FNR family of prokaryotic transcription factors (19, 20, 32), and recent experimental evidence suggests that PrfA, like CRP, requires the presence of a cofactor for full activity (26, 27, 36). It has been demonstrated that a number of L. monocytogenes strains that constitutively overexpress PrfA-regulated gene products contain a mutant prfA allele (prfA*) with a single amino acid substitution (Gly145→Ser) (27). These prfA* mutants resemble crp* mutants which contain an analogous mutation in a region of PrfA-CRP homology and which are active in the absence of the cofactor cAMP (16, 18). Preliminary experiments suggest that cAMP does not influence PrfA activity (36; L. M. Shetron-Rama and N. E. Freitag, unpublished data). Vega et al. (36) have demonstrated that PrfA* has an increased binding affinity for target DNA. It is possible that the activated form of PrfA is required for full expression of certain target promoters and that one of these promoters is that of actA. If so, this would suggest that PrfA activation does not occur in the B. subtilis system, and it accentuates the difference that exists between hly, mpl, and actA expression.

The results presented in this study indicate that sequence variations within the PrfA DNA binding sites of L. monocytogenes virulence gene promoters can produce a wide range of effects on gene expression. It is necessary, however, to confirm that the behavior observed for promoter fusions in the heterologous B. subtilis expression system reflects what is actually occurring in L. monocytogenes. Preliminary experiments indicate that the behavior observed for substitutions within the actA promoter in B. subtilis closely corresponds to what is observed when the same substitutions are introduced into L. monocytogenes (L. M. Shetran-Rama and N. E. Freitag, unpublished data). We are in the process of using both heterologous systems and defined mutations within L. monocytogenes to better define the activation steps and cofactors required for optimal expression of PrfA-dependent virulence genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathleen Jacobs for technical assistance in the construction of plasmids for this study. We thank David Dubnau for very helpful discussions and the reviewers of the manuscript for insightful criticism and valuable suggestions.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI41816 from the National Institutes of Health. N.E.F. thanks the Public Health Research Institute for initial support and encouragement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Böckmann R, Dickneite C, Middendorf B, Goebel W, Sokolovic Z. Specific binding of the Listeria monocytogenes transcriptional regulator PrfA to target sequences requires additional factor(s) and is influenced by iron. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:643–653. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohne J, Sokolovic Z, Goebel W. Transcriptional regulation of prfA and PrfA-regulated virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1141–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brundage R A, Smith G A, Camilli A, Theriot J A, Portnoy D A. Expression and phosphorylation of the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11890–11894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cossart P, Kocks C. The actin-based motility of the facultative intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dabiri G A, Sanger J M, Portnoy D A, Southwick F S. Listeria monocytogenes moves rapidly through the host cytoplasm by inducing directional actin assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6068–6072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickneite C, Böckmann R, Spory A, Goebel W, Sokolovic Z. Differential interaction of the transcription factor PrfA and the PrfA-activating factor (Paf) of Listeria monocytogenes with target sequences. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:915–928. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domann E, Leimeister-Wächter M, Goebel W, Chakraborty T. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and identification of a metalloprotease gene from Listeria monocytogenes that is species specific and physically linked to the listeriolysin gene. Infect Immun. 1991;59:65–72. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.65-72.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domann E, Wehland J, Rohde M, Pistor S, Hartl M, Goebel W, Leimeister-Wachter M, Wuenscher M, Chakraborty T. A novel bacterial gene in Listeria monocytogenes required for host cell microfilament interaction with homology to the proline-rich region of vinculin. EMBO J. 1992;11:1981–1990. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freitag N E, Rong L, Portnoy D A. Regulation of the prfA transcriptional activator of Listeria monocytogenes: multiple promoter elements contribute to intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2537–2544. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2537-2544.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitag N E, Youngman P, Portnoy D A. Transcriptional activation of the Listeria monocytogenes hemolysin gene in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1293–1298. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1293-1298.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray M L, Killinger A H. Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infections. Bacteriol Rev. 1966;30:309–382. doi: 10.1128/br.30.2.309-382.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Innis M A, Gelfand D H. Optimization of PCRs. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ireton K, Cossart P. Host-pathogen interactions during entry and actin-based movement of Listeria monocytogenes. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:113–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenney T J, Moran C P., Jr Genetic evidence for interaction of ςA with two promoters in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3282–3290. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3282-3290.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenney T J, Moran C P., Jr Organization and regulation of an operon that encodes a sporulation-essential Sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3329–3339. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3329-3339.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Adhya S, Garges S. Allosteric changes in the cAMP receptor protein of Escherichia coli: hinge reorientation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9700–9704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocks C, Gouin E, Tabouret M, Berche P, Ohayon H, Cossart P. L. monocytogenes-induced actin assembly requires the actA gene product, a surface protein. Cell. 1992;68:521–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90188-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolb A, Busby S, Buc H, Garges S, Adhya S. Transcriptional regulation by cAMP and its receptor protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:749–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreft J, Bohne J, Gross R, Kestler H, Sokolovic Z, Goebel W. Control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence genes by the transcriptional regulator PrfA. In: Rappuoli R, Scarlato V, Arico B, editors. Signal transduction and bacterial virulence. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1995. pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lampidis R, Gross R, Sokolovic Z, Goebel W, Kreft J. The virulence regulator protein of Listeria ivanovii is highly homologous to PrfA from Listeria monocytogenes and both belong to the Crp-Fnr family of transcription regulators. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leimeister-Wachter M, Haffner C, Domann E, Goebel W, Chakraborty T. Identification of a gene that positively regulates expression of listeriolysin, the major virulence factor of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8336–8340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mengaud J, Dramsi S, Gouin E, Vazquez-Boland J A, Milon G, Cossart P. Pleiotropic control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors by a gene that is autoregulated. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2273–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moors M A, Levitt B, Youngman P, Portnoy D A. Expression of listeriolysin O and ActA by intracellular and extracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:131–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.131-139.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mounier J, Ryter A, Coquis-Rondon M, Sansonetti P J. Intracellular and cell-to-cell spread of Listeria monocytogenes involves interaction with F-actin in the enterocytelike cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1048–1058. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1048-1058.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portnoy D A, Freitag N E. Regulation of the entry into host cytoplasm and cell-to-cell spread of Listeria monocytogenes. In T. K. Korhonen, T. Hovi, and P. H. Makela (ed.), Molecular recognition in host-parasite interactions: mechanisms in viral, bacterial, and parasite infections. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ripio M-T, Brehm K, Lara M, Suárez M, Vázquez-Boland J-A. Glucose-1-phosphate utilization by Listeria monocytogenes is PrfA dependent and coordinately expressed with virulence factors. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7174–7180. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7174-7180.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ripio M-T, Dominguez-Bernal G, Lara M, Suárez M, Vázquez-Boland J-A. A Gly145Ser substitution in the transcriptional activator PrfA causes constitutive overexpression of virulence factors in Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1533–1540. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1533-1540.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanger J M, Mittal B, Southwick F S, Sanger J W. Analysis of intracellular motility and actin polymerization induced by Listeria monocytogenes in PtK2 cells. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:415A. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeliger H P R. Listeriosis—history and actual developments. Infection. 1988;16:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01639726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan B, Klarsfeld A, Msadek T, Cossart P. Differential activation of virulence gene expression by PrfA, the Listeria monocytogenes virulence regulator. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6469–6476. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6469-6476.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheehan B, Klarsfeld A, Msadek T, Cossart P. A single substitution in the putative helix-turn-helix motif of the pleiotropic activator PrfA attenuates Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;20:785–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan B, Kocks C, Dramsi S, Gouin E, Klarsfeld A D, Mengaud J, Cossart P. Molecular and genetic determinants of the Listeria monocytogenes infectious process. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;192:187–216. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78624-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith G A, Portnoy D A. How the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein converts actin polymerization into a motile force. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:272–276. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theriot J A, Mitchison T J, Tilney L G, Portnoy D A. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 1992;357:257–260. doi: 10.1038/357257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilney L G, Connelly P S, Portnoy D A. The nucleation of actin filaments by the bacterial intracellular pathogen, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2979–2988. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vega Y, Dickneite C, Ripio M-T, Böckmann R, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Novella S, Dominguez-Bernal G, Goebel W, Vazquez-Boland J A. Functional similarities between the Listeria monocytogenes virulence regulator PrfA and cyclic AMP receptor protein: the PrfA* (Gly145Ser) mutation increases binding affinity for target DNA. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6655–6660. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6655-6660.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youngman P. Plasmid vectors for recovering and exploiting Tn917 transpositions in Bacillus and other gram-positive bacteria. In: Hardy K, editor. Plasmids: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1987. pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Youngman P, Poth H, Green B, York K, Olmedo G, Smith K. Methods for genetic manipulation, cloning, and functional analysis of sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuber P, Losick R. Use of lacZ fusion to study the role of the spoO genes of Bacillus subtilis in developmental regulation. Cell. 1983;35:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]