Abstract

Smoke alarms with lithium batteries have been marketed as long life or “10-Year Alarms.” Previous work has drawn into question the actual term of functionality for lithium battery alarms. This article reports on observed smoke alarm presence and functionality in a sample of 158 homes that had participated in a fire department smoke alarm installation program 5 to 7 years prior to the observations. A total of 391 alarms were originally installed in the 158 homes that completed the revisit. At the time of the revisit, 217 of those alarms were working (54%), 28 were nonworking (7%), and 146 were missing (39%). Of the 158 homes that completed the revisit, n = 62 (39%) had all their originally installed project alarms up and working at the revisit. Respondents who reported owning their homes or who reported living in their home for 6 or more years were significantly more likely to maintain all of their project alarms than renters or those living in their homes for 5 or fewer years. Smoke alarm installation programs should consider revisiting homes within 5 to 7 years postinstallation to inspect and replace any missing or nonfunctioning alarms. We recommend programs conducting community risk reduction programs track and plan installations and revisits to improve smoke alarm coverage.

In 2016, there were approximately 371,500 home structure fires resulting in 2735 civilian deaths and 10,750 civilian injuries.1 There is a 40%2,3 lower risk of death from fires in homes with at least one smoke alarm. It is well documented that many homes do not have the recommended number of smoke alarms.4–8 Smoke alarm distribution programs have been proven effective at increasing the prevalence of smoke alarms in homes.9–12 Lithium battery–powered smoke alarms are functional for a longer period of time than carbon–zinc battery alarms.13,14

Though marketed as “10-Year Alarms,” studies have suggested that lithium battery alarms may have functional lifetimes less than 10 years. For example, an 8- to 10-year follow-up evaluation of a community-based program that had installed 601 lithium battery alarms in homes found that 33% of those alarms were functional, 37% were missing, and 30% were nonfunctional; of the nonfunctional alarms, the majority had dead (43%) or missing (17%) batteries.15 The percentage of functional lithium battery alarms over time was also determined from another evaluation of a similar community-based program: 83.5% of alarms that were 2 years old were functional; in comparison, less than 25% of alarms that were 8 to 10 years old were functional.16 In a study by McCoy et al of 429 6- to 10-year-old lithium battery alarms, 268 (52%) were not functional. The primary cause for nonfunctioning alarms in this study was battery-related issues (201, 75%): 121 had no battery, 23 had a working battery that had been disconnected, 18 had a nonworking battery that had been disconnected, 25 had a connected but dead original battery, and 14 had a connected but dead nonoriginal battery.16 McCoy et al reported that just 54% of lithium battery alarms were still present and only about 20% of the homes had at least one working program alarm after a community-based installation program.16 This body of previous work on the functionality of lithium battery alarms at long-term follow-up was based on alarms without a hush feature and with removable lithium batteries.15,16 By 2012, most lithium battery smoke alarms on the market were sealed to eliminate battery poaching and included a hush feature to minimize removal and tampering due to nuisance alarms.

Our study further examines the functionality and presence of sealed lithium battery smoke alarms with a hush feature 5 to 7 years postinstallation in an urban population as well as residents’ reported reasons for why smoke alarms were missing or disabled. The Johns Hopkins Home Safety Project was a community-based intervention trial in partnership with the Baltimore City Fire Department which installed free smoke alarms in Baltimore City homes in 2012 to 2013, the results of which have been reported previously.17,18 This article aims to report on the presence and functionality of the originally installed alarms by describing the observed number of working smoke alarms, self-reported reasons for nonworking alarms 5 to 7 years after installation, and characteristics of households likely to maintain their alarms that were visited as part of this Johns Hopkins Home Safety Revisit Project. The unique contributions of this study are that it reports on sealed lithium battery smoke alarms with a hush feature, which is the currently recommended best practice, and residents’ reported reasons why alarms were not working or absent at follow-up.

METHODS

Study Design

The Johns Hopkins Home Safety Revisit Project took place between May and December 2017. Study participants of the Johns Hopkins Home Safety Project who had previously agreed to a follow-up visit were sent a letter notifying them that a team of data collectors would be present in their neighborhood revisiting homes to check their smoke alarms. The letter provided a telephone number to call if the resident wanted to opt out of the revisit.

Teams of at least two data collectors canvassed neighborhoods by census track knocking on doors of homes asking residents if they wanted to participate in the revisit project. To be eligible for the home safety revisit, participants must have been at least 18 years of age, lived in the home of the listed address, and spoke and understood English. Homes were visited five times before being coded as no answer.

If residents were interested and eligible, data collectors obtained informed consent and then administered a brief survey and tested alarms on all accessible levels of the home. Participants with missing or nonworking alarms were advised to call to Baltimore City’s nonemergency 311 number for referral to Baltimore City Fire Department’s free smoke alarm installation program. Following completion of the home safety revisit, a $10 gift card was provided in appreciation for the participant’s time. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Participants reported sociodemographic information including age, number of individuals in the home, presence of children and seniors living in the home, length of tenancy, education level, and whether the family received government financial assistance. A brief survey on smoke alarm status and testing behavior was completed by the participants. Data collectors were provided with information about the levels on which alarms had been installed during the original visits. Testing the alarms involved pressing down and holding the test button of the smoke alarm to hear a chirp. An alarm was coded as working if the chirp was heard.

Smoke Alarm Status

Data collectors recorded if smoke alarms were present and if present whether they were working. When smoke alarms that had been installed as part of the original program were missing or not working, data collectors asked residents if they knew the reason smoke alarms were missing. The open-ended responses were subsequently coded and summarized. A binomial yes/no variable was created distinguishing those households that had all alarms from the original visit up and working at the revisit from those that had one or more project alarms missing or nonfunctioning.

Testing Behaviors

Data collectors asked residents to report the last time they had tested their alarms. If residents reported the alarms had been tested in the previous year, they were asked to report on their testing frequency. When residents reported the alarms had not been tested, the data collectors asked residents to report their reasons for not testing.

Data Analysis

Demographics, smoke alarm status, and reported testing behavior were tabulated. Demographics were cross-tabulated with the derived yes/no variable for households with all alarms working and differences were tested using chi-square test. A multiple logistic regression analysis was run to estimate the odds ratio of maintaining all smoke alarms for homeowners vs renters and those with 6 or more years of tenancy vs 5 or fewer years of tenancy, adjusting for receipt of government financial aid. Those observations with missing or don’t know responses were omitted from the regression analysis. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample

Out of 550 homes invited to participate, 158 were enrolled and completed the revisit (Table 1).

Table 1.

End status, N = 550 attempted homes

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Enrolled | 158 | 28.73 |

| Ineligible | 13 | 2.36 |

| Refused | 137 | 24.91 |

| Vacant | 71 | 12.91 |

| No answer | 171 | 31.09 |

Demographics

Homes were primarily owned (67%), with a median length of tenancy over 11 years (59%). The people living in the home most often included two to three people (49%), with no children (70%), and no seniors older than 64 years (57%). The majority of respondents were those who had lived in the home at the time of the original alarm installation program (69%), had at least a high school diploma (88%), and did not receive income assistance (57%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample demographics, N = 158 enrolled homes

| Frequency N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education | Less than high school diploma | 19 (12) |

| High diploma or GED | 62 (39) | |

| Greater than high school | 25 (16) | |

| Completed college or above | 52 (33) | |

| Homeowner status | Own | 106 (67) |

| Rent | 50 (32) | |

| I do not know | 2 (1) | |

| Receive income assistance | Yes | 66 (42) |

| No | 90 (57) | |

| I do not know | 2 (1) | |

| Number of people in home* | 1 person | 37 (24) |

| 2 to 3 people | 77 (49) | |

| 4 to 6 people | 40 (25) | |

| 7 or more people | 3 (2) | |

| Children <18 years in home* | None | 110 (70) |

| 1 child | 25 (16) | |

| 2 to 3 children | 19 (12) | |

| 4 or more children | 3 (2) | |

| Seniors >64 years in home* | None | 89 (57) |

| 1 senior | 49 (31) | |

| 2 to 3 seniors | 19 (12) | |

| Length of tenancy | Less than 6 months | 11 (7) |

| Six to 11 months | 6 (4) | |

| 1 to 5 years | 23 (15) | |

| 6 to 10 years | 23 (15) | |

| 11 years or more | 94 (59) | |

| I do not know | 1 (1) | |

| Did anyone who lives here now live here at the time of installation of smoke alarms? | Yes | 109 (69) |

| No | 45 (28) | |

| I do not know | 4 (3) |

*Data are unavailable for n = 1 participant.

Smoke Alarm Status

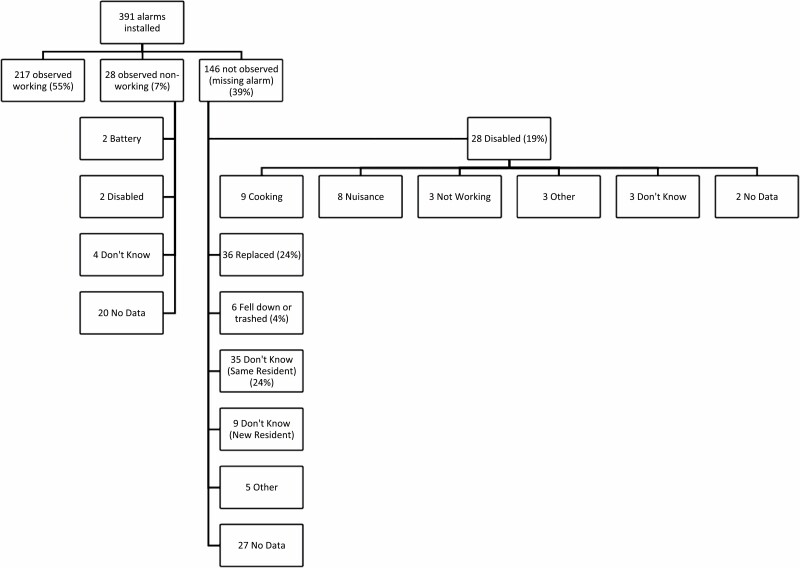

A total of 391 alarms were originally installed in the 158 homes that completed the revisit. At the time of the revisit, 217 of those alarms were working (54%), 28 were nonworking (7%), and 146 were missing (39%) (Figure 1). Of the missing alarms, 17% (n = 26) had been taken down by the resident, 16% (n = 24) had been replaced, and 4% had fallen down. The most common reasons for taking the alarm down were nuisance and cooking-related alarming. No detail about the reason for missingness was available for 63% (n = 98) of the missing alarms because respondents could not recall, had not lived there, or were not asked to provide additional detail by data collectors.

Figure 1.

Smoke alarm flow diagram.

Of the 158 homes that completed the revisit, n = 62 (39%) had all their originally installed project alarms up and working at the revisit. There were no differences in the number of smoke alarms installed between those homes that maintained their alarms and those that did not. Respondents who reported owning their homes or who reported living in their home for 6 or more years were significantly more likely to maintain all of their project alarms than renters or those living in their homes for 5 or fewer years (48% of homeowners vs 24% of renters; P = .005 and 45% of tenancy 6 or more years vs 21% of tenancy 5 or fewer years; P = .006). In a multiple logistic regression among n = 152 households with complete data, adjusted for receiving government financial aid, homeowners had 2.64 times higher odds than renters (95% CI 1.11–6.28) and those with 6 or more years of tenancy had 2.50 times higher odds than those with 5 or fewer years of tenancy (95% CI 1.00–6.19) to maintain all project alarms.

Survey Questions

The majority of respondents reported having tested the alarms within the last year (n = 95; 60%). Among those respondents who reported testing their alarms within the past year, they most often reported testing them monthly (28%) or every 3 to 6 months (30%). Ten respondents stated that they had never tested their smoke alarms; when asked why, one-half could not provide a reason. Most respondents (76%) thought all of their alarms were working, primarily stating that because the alarms had recently been tested (36%) or sounded (37%). Of the 19 respondents who said they did not think their alarms were working, one-half stated that alarms were not repaired or replaced because they had not gotten around to replacing the alarms or batteries (Table 3).

Table 3.

Knowledge of smoke alarm status and reported testing behaviors, N = 158

| Frequency N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| When was the last time you or someone else tested the smoke alarms in your home? | Within the last week | 20 (13) |

| Within the last month | 31 (20) | |

| Within the last 6 months | 33 (21) | |

| Within the last year | 11 (7) | |

| More than 1 year ago | 28 (18) | |

| Never | 10 (6) | |

| I do not know | 25 (16) | |

| If within the last year: About how often were smoke detector(s) tested? (n = 87) | At least monthly | 24 (28) |

| Every 3 to 6 months | 26 (30) | |

| Yearly | 15 (17) | |

| Once every few years | 2 (2) | |

| Never | 8 (9) | |

| When the alarm chirps | 5 (6) | |

| Other | 7 (8) | |

| If never: What were the reasons that smoke detector(s) were not tested? (n = 8) | Did not know you should test | 1 (12.5) |

| Did not think it was important enough | 2 (25) | |

| Did not know how to test | 1 (12.5) | |

| Do not know | 4 (50) | |

| Do you think all of your smoke detectors are working? | Yes | 120 (76) |

| No | 19 (12) | |

| I do not know | 19 (12) | |

| If Yes: What makes you say that? (n = 117) | We tested them | 42 (36) |

| We took out the battery because it was a nuisance | 1 (1) | |

| The alarm sounded recently (ie, while cooking) | 44 (37) | |

| We recently changed the batteries | 4 (4) | |

| Other | 26 (22) | |

| If No: What is the main reason the alarms were not fixed or replaced? (n = 16) | Did not get around to it | 4 (25) |

| Did not know how to fix or replace | 1 (6) | |

| Cannot install or fix them | 2 (13) | |

| They are a nuisance when they go off | 1 (6) | |

| It is the landlord’s responsibility | 1 (6) | |

| The batteries are old or dead | 4 (25) | |

| Not sure | 3 (19) |

Discussion

Perhaps, the most important question this study helps to shed light on is the question of how often smoke alarm installation programs should revisit homes after installation. Our analysis indicates that the majority (54%) of long-life lithium battery alarms were in place and operational 5 to 7 years postinstallation. To address the 46% of alarms that were missing or not operational, residents could clearly benefit from a repeat visit from the Fire Department within 5 to 7 years to inspect and replace any missing or nonfunctioning alarms. We recommend programs conducting community risk reduction programs track and plan installations and revisits to improve smoke alarm coverage. It is unknown to what extent the community risk reduction program currently routinely plans and conducts revisits systematically based on installation date. Advances in technology should be used to assist with tracking and planning smoke alarm visits.

This recommendation would also help to address the finding that only 39% of homes maintained all of their originally installed smoke alarms. This is an underestimate of maintenance as it does not reflect households where a project alarm was replaced by the occupants or other installation programs. Homeowners and those with longer tenancy were more likely to still have all of the smoke alarms installed in their home. These associations are held in a multivariable analysis. This indicates that households with greater stability may need less attention than those with higher turnover. Rental properties and housing codes pertaining to rental properties offer an opportunity to ensure alarms are present and functional at property turnover.

Our results are similar to previous work that demonstrated substantial missingness of lithium battery alarm more than 5 years postinstallation.15,16 In our study, missing alarms (37%) were more of a problem than smoke alarms observed to be nonfunctioning (7%). Residents reported that for 19% of the missing alarms, they (or someone in their household) had purposefully disabled the alarm. We found it interesting that replacement was the reason for 24% of the missing alarms. In some cases, residents reported that the fire department had returned at a later date and replaced all alarms. In other cases, residents reported that other community service programs had conducted a home visit and replaced the alarms. These instances support a need for coordination between programs in the same neighborhood as well as a need for the fire department to use a marking and tracking system to maximize efficiencies in installation programs. However, for many alarms, the resident simply did not know what happened to the alarm or had not lived at the residence during the previous installation.

There were several limitations to this study. Only 28% of the original sample completed the revisit; the extent to which those that participated represent the full sample is unknown. An additional limitation of this study is that little detail is available to explain the reason for missing alarms. This lack of clarity is understandable, given the 5-year window between smoke alarm installation and follow-up, the inclusion of households that turned over residents since the fire department visit, and the unknown dynamics with multiple people living in the home who may have removed an alarm. Data collectors’ notes provide some anecdotal information such as respondents not having been aware of the original fire department visit, suspicion that another family member might have information about the reason, and that they had not been living at the address when the alarms were installed. However, the available responses provide new insight into the reasons residents take down smoke alarms in their homes. That many residents did not know the reason for their missing or nonworking alarm underscores the importance of regular smoke alarm home visits every 5 to 7 years. We additionally recommend that community risk reduction programs stress the availability of the hush feature to quiet nuisance alarms and encourage residents to speak to family members who are not present during the installation visit to ensure all members of the household are made aware of alarm features.

Source of Funding: Funding for the parent project was provided to the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1R18CE001339): Dissemination of Research in Child Safety; and NIH/National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (1R01 H059216): Community Partnerships for Child Safety. Funding for this follow-up study was provided by Vision 20/20.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Contributor Information

Wendy Shields, Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Elise Omaki, Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Joel Villalba, Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Andrea Gielen, Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

References

- 1. Haynes H. Fire loss in the United States during 2016. NFPA J 2017;111:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahrens M. U.S. experience with sprinklers. Quincy (MA): National Fire Protection Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Istre GR, McCoy MA, Osborn Let al. Deaths and injuries from house fires. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1911–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ballesteros MF, Kresnow MJ. Prevalence of residential smoke alarms and fire escape plans in the U.S.: results from the Second Injury Control and Risk Survey (ICARIS-2). Public Health Rep 2007;122:224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parker EM, Gielen AC, McDonald EMet al. Fire and scald burn risks in urban communities: who is at risk and what do they believe about home safety? Health Educ Res 2013;28:599–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sidman EA, Grossman DC, Mueller BA. Comprehensive smoke alarm coverage in lower economic status homes: alarm presence, functionality, and placement. J Community Health 2011;36:525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu Y, Holland AE, Mack Ket al. Disparities in the prevalence of smoke alarms in U.S. households: conclusions drawn from published case studies. J Safety Res 2011;42:409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peek-Asa C, Allareddy V, Yang Jet al. When one is not enough: prevalence and characteristics of homes not adequately protected by smoke alarms. Inj Prev 2005;11:364–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ballesteros MF, Jackson ML, Martin MW. Working toward the elimination of residential fire deaths: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Smoke Alarm Installation and Fire Safety Education (SAIFE) program. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005;26:434–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gielen AC, Shields W, Frattaroli Set al. Enhancing fire department home visiting programs: results of a community intervention trial. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:e250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ta VM, Frattaroli S, Bergen Get al. Evaluated community fire safety interventions in the United States: a review of current literature. J Community Health 2006;31:176–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper NJ, Kendrick D, Achana Fet al. Network meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to increase the uptake of smoke alarms. Epidemiol Rev 2012;34:32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peek-Asa C, Yang J, Hamann Cet al. Smoke alarm and battery function months after installation: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:368–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang J, Peek-Asa C, Jones MPet al. Smoke alarms by type and battery life in rural households: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:20–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jackson M, Wilson J, Akoto Jet al. Evaluation of fire-safety programs that use 10-year smoke alarms. J Community Health 2010;35:543–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCoy MA, Roper C, Campa Eet al. How long do smoke alarms function? A cross-sectional follow-up survey of a smoke alarm installation programme. Inj Prev 2014;20:103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gielen AC, Shields W, Frattaroli Set al. Enhancing fire department home visiting programs: results of a community intervention trial. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:e250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stepnitz R, Shields W, McDonald E, Gielen A. Validity of smoke alarm self-report measures and reasons for over-reporting. Inj Prev 2012;18:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]