Abstract

Methanococcus voltae is a mesophilic archaeon with flagella composed of flagellins that are initially made with 11- or 12-amino-acid leader peptides that are cleaved prior to incorporation of the flagellin into the growing filament. Preflagellin peptidase activity was demonstrated in immunoblotting experiments with flagellin antibody to detect unprocessed and processed flagellin subunits. Escherichia coli membranes containing the expressed M. voltae preflagellin (as the substrate) were combined in vitro with methanogen membranes (as the enzyme source). Correct processing of the preflagellin to the mature flagellin was also shown directly by comparison of the N-terminal sequences of the two flagellin species. M. voltae preflagellin peptidase activity was optimal at 37°C and pH 8.5 and in the presence of 0.4 M KCl with 0.25% (vol/vol) Triton X-100.

All of the major subgroupings of archaea, including methanogens, extreme halophiles, and sulfur-dependent thermophiles and hyperthermophiles, have members that possess flagella that look superficially like bacterial flagella (10). However, recent evidence has indicated that the archaeal flagellum is a unique motility structure, distinct from that of bacteria in composition and likely assembly (4, 10). One major distinction is that the assembly of archaeal flagella requires the posttranslational cleavage of a short (11- or 12-amino-acid) leader peptide (2, 13) from the precursor form of the flagellin monomer (preflagellin) before its incorporation into the growing filament. Bacterial flagellins are not made with leader peptides (12).

Previously, in Methanococcus voltae, four flagellin genes (flaA, flaB1, flaB2, and flaB3) carried by two transcriptional units were identified (13). One transcriptional unit contains only flaA; the other, polycistronic transcriptional unit (at least 5.4 kb in length), containing flaB1, flaB2, flaB3, and a number of presumed flagellum accessory genes, initiates at flaB1 and extends to at least the end of flaG (13; D. P. Bayley, J. D. Correia, and K. F. Jarrell, unpublished data). N-terminal (14), transcriptional (13), and mutational (9) analyses have provided evidence that flaB1 and flaB2 encode the major flagellins in M. voltae. Comparison of the N-terminal sequence of one purified flagellin with the amino acid sequence predicted from the gene sequence (13) confirmed the presence of a 12-amino-acid leader peptide. Similarly, in the related methanogen Methanococcus vannielii, comparison of the N-terminal sequences obtained from the two major flagellins of purified flagellar filaments with the deduced amino acid sequence of the cloned genes indicated the presence of 12-amino-acid leader peptides on the FlaB1 and FlaB2 flagellins (2). The presence of leader peptides on archaeal flagellins indicated that enzymatic activity must be present in archaeal cells to process the preflagellins.

Two different substrates were used for the determination of preflagellin peptidase activity. One preflagellin substrate was prepared by the expression of M. voltae FlaB2 in Escherichia coli (designated strain KJ91) using the T7 polymerase system (3, 18). A second substrate for the preflagellin peptidase was M. voltae FlaB1 with a C-terminal polyhistidine tag (His-tag). M. voltae flaB1 was cloned into the multiple cloning site of the pET23a+ vector (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.) at NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. To do so, forward (5′ GGAATCCATATGAACATAAAAGAATT 3′) and reverse (5′ CCGCTCGAGTTGTAATTCAACAACTT 3′) PCR primers were designed to amplify flaB1, as well as generate a 5′ NdeI site and a 3′ XhoI site (underlined). In addition, the stop codon was deleted, creating an in-frame fusion with a His-tag sequence corresponding to the C-terminal end of the protein. The template for PCR was pKJ43, which contains a 2-kb PstI fragment encompassing flaB1 (13). Amplification of flaB1 was performed with Pwo DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Laval, Quebec, Canada) with the following program: 95°C for 5 min and 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 50°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 2 min. The final cycle had an extension time of 5 min. pET23a+ containing flaB1 (designated pKJ202) was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pLysS. These cells were grown in 50 ml of Luria-Bertani medium to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 to 1, induced with 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and grown for an additional 2 to 3 h. Membranes for use in the preflagellin peptidase assay were prepared as previously described (3).

To isolate methanogen membranes, methanogens grown overnight as previously described (15) were harvested aerobically by centrifugation, and the osmotically sensitive cells were lysed by the addition of sterile distilled water. The resulting envelopes were collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415; Brinkmann Instruments, Inc., Westbury, N.Y.) for 10 min and resuspended in sterile distilled water.

The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction mixture (based on the prepilin peptidase assay for Pseudomonas aeruginosa [17]) contained approximately 72 μg of induced E. coli KJ91 membranes (as the substrate) combined with approximately 18 μg of methanogen membranes (as the enzyme source) in a final volume of 60 μl of 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Each of the preflagellin peptidase assays was conducted near the optimum growth temperature of the methanogen tested: 37°C for reactions involving a mesophilic archaeon, 60°C for Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus, and 80°C for Methanococcus jannaschii and Methanococcus igneus. The reaction was started by the addition of the methanogen membranes and stopped by the addition of 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer (ESB) (0.0625 M Tris [pH 6.8], 1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% bromophenol blue) to 10-μl aliquots (removed at time points of 0, 2, 10, and 30 min) and boiling for 5 min. The activity of a preflagellin peptidase was observed by immunoblotting experiments to detect unprocessed and processed preflagellin with antiserum raised against the M. voltae FlaB2 flagellin (3).

Samples for N-terminal sequencing were prepared as previously described (3). Sequencing was performed by David Watson (National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Preflagellin peptidase activity of M. voltae.

M. voltae FlaB2, expressed in E. coli by the pT7 system (18), was detected in the crude E. coli membranes as a 26.5-kDa protein by both Coomassie blue staining and immunoblotting with flagellin antibody (Fig. 1A). N-terminal analysis of the expressed protein revealed the first 10 amino acids to be MKIKEFMSNK, which match exactly the predicted FlaB2 sequence with the attached leader peptide (3, 13). In the case of FlaB1, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analyses of induced E. coli BL21(DE3)-pLysS carrying pKJ202 revealed an induction product migrating at approximately 29 kDa, detected by both Coomassie blue staining and immunoblotting with anti-FlaB2 serum (data not shown).

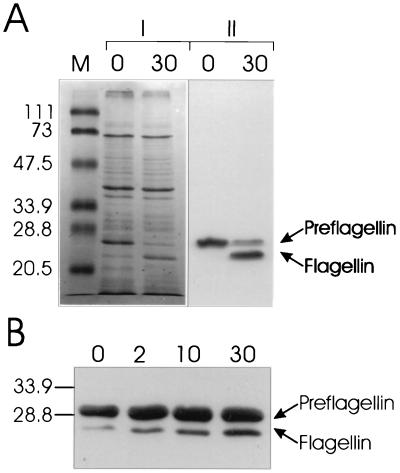

FIG. 1.

Processing of M. voltae preflagellins FlaB1 and FlaB2 by the M. voltae preflagellin peptidase. (A) The preflagellin peptidase reaction was performed with approximately 72 μg of induced E. coli KJ91 membranes (FlaB2 substrate source) combined with approximately 18 μg of M. voltae membranes (enzyme source) in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.5) containing 0.25% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and 0.4 M KCl (optimized conditions), at a reaction temperature of 37°C. Ten-μl samples were taken at 0- and 30-min time points and immediately mixed with 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Twenty- and 10-μl samples were analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (|) and immunoblotting with a primary antibody dilution of 1:10,000 (∥), respectively. The relative mobility of prestained SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis low-range molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad) are indicated in kilodaltons (lane M). (B) The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction was performed with approximately 72 μg of induced E. coli KJ202 membranes (FlaB1 substrate source) combined with approximately 18 μg of M. voltae membranes (enzyme source) in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Samples removed at 0, 2, 10, and 30 min were similarly prepared and 10-μl aliquots were examined by immunoblotting with anti-FlaB2 antiserum. The positions of 33.9- and 28.8-kDa molecular mass markers are indicated.

E. coli membranes containing FlaB2 were mixed with M. voltae envelopes in the presence of 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and samples taken at various time points were analyzed by immunoblotting with antiflagellin antiserum. Western blot analysis of the preflagellin peptidase assay clearly demonstrated the appearance, with time, of a second cross-reactive band with greater electrophoretic mobility than the 26.5-kDa preflagellin (Fig. 1A). This additional band increased in intensity with time, and its size corresponded to that expected for the processed flagellin. The N-terminal sequence determined for this smaller (25 kDa), cross-reactive band was ASGIGT(L/G)IVF, indicating that it was indeed the product of the FlaB2 precursor after cleavage of its 12-amino-acid N-terminal leader peptide (13). The 25-kDa flagellin was absent when the assay was performed without the addition of M. voltae membranes or with the addition of M. voltae membranes previously boiled for 5 min (data not shown). The addition of cardiolipin was not necessary for M. voltae preflagellin cleavage (data not shown), unlike the in vitro prepilin peptidase assay system of P. aeruginosa, where an acidic phospholipid is an essential component (17). In addition, since all assays were conducted aerobically, the preflagellin peptidase did not require the strict anaerobic conditions that are essential for the growth of M. voltae.

E. coli membranes containing FlaB1 were similarly incubated with M. voltae membranes in the presence of 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and the appearance of mature flagellin was observed by immunoblotting with anti-FlaB2 serum (Fig. 1B). Although both overexpressed FlaB2 and polyhistidine-tagged FlaB1 were suitable substrates of the preflagellin peptidase, the work described below utilized the FlaB2 substrate.

Optimization of the preflagellin peptidase assay.

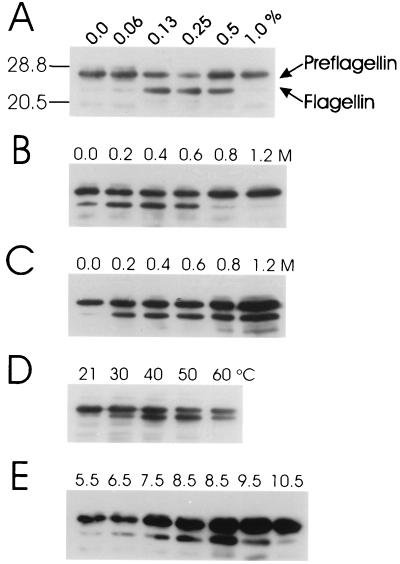

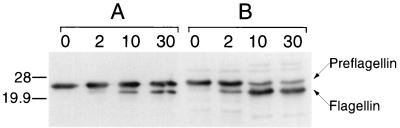

Preflagellin cleavage activity required the addition of a buffer containing Triton X-100 or Nonidet P-40 as the solubilizing detergent. The processed flagellin was not evident in immunoblots when the assay was performed in reaction buffer that did not contain detergent (data not shown). Furthermore, preflagellin peptidase activity was not detected when Triton X-100 was replaced by a number of other detergents tested at a final concentration of 0.5% (vol/vol), including Tween 20, Tween 80, Brij 58, and SDS (data not shown). Experiments performed to maximize preflagellin cleavage involved varying the detergent concentration (Triton X-100), the salt concentration (KCl and NaCl), pH, and temperature (Fig. 2). A comparison of the initial assay conditions based on the prepilin peptidase system (25 mM HEPES buffer [pH 7.5] containing 0.5% [vol/vol] Triton X-100 at 37°C) with the optimized assay conditions developed in this work (25 mM HEPES buffer [pH 8.5] containing 400 mM KCl and 0.25% [vol/vol] Triton X-100 at 37°C) is presented in Fig. 3. Under optimized conditions, the processed form of the flagellin becomes the predominant of the two flagellin species over the 30-min time course of the reaction.

FIG. 2.

Optimization of the in vitro preflagellin peptidase reaction for detergent, salt, temperature, and pH. For all reactions, 10-μl samples were removed at 10 min and then immediately mixed with 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer and boiled for 5 min; 10-μl aliquots were examined by immunoblotting with a primary antibody dilution of 1:10,000. (A) The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction was performed with approximately 72 μg of induced E. coli KJ91 membranes (substrate source) combined with approximately 18 μg of M. voltae membranes (enzyme source) in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing varying final concentrations of Triton X-100 (0.0, 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0% [vol/vol]). (B) The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.5] containing 0.5% [vol/vol] Triton X-100) was supplemented with KCl to a final concentration of 0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, or 1.2 M. (C) The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction was supplemented with NaCl to a final concentration of 0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, or 1.2 M. (D) The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction was performed at reaction temperatures of 21, 30, 40, 50, and 60°C. (E) The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction was performed in 25 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid buffer (pH 5.5 and 6.5), 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5 and 8.5) and 25 mM 1,3,-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino]propane buffer (pH 8.5, 9.5, and 10.5).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the standard and optimized reaction conditions for the in vitro processing of M. voltae FlaB2 preflagellin by the M. voltae preflagellin peptidase. The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction (A) was performed with approximately 72 μg of induced E. coli KJ91 membranes (substrate source) combined with approximately 18 μg of M. voltae membranes (enzyme source) in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and the optimized preflagellin peptidase reaction (B) was performed in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.5) containing 0.4 M KCl and 0.25% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Ten-microliter samples were removed at 0, 2, 10, and 30 min and then immediately mixed with 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer and boiled for 5 min; 10-μl aliquots were examined by immunoblotting with a primary antibody dilution of 1:10,000. The positions of 28- and 19.9-kDa molecular mass markers are indicated.

A nonflagellated M. voltae mutant (M. voltae P-2 [9]) was also examined for preflagellin peptidase activity under the standard reaction conditions. This mutant has an insertional vector located in flaB2, which also results in a polar effect on the cotranscribed downstream genes. Preflagellin peptidase activity with M. voltae P-2 membranes was comparable to that observed in the membranes of wild-type M. voltae cells after a reaction time of 30 min (data not shown), indicating that the preflagellin peptidase activity is not attributable to the products encoded by flaC-flaG.

Heterologous preflagellin peptidase activity.

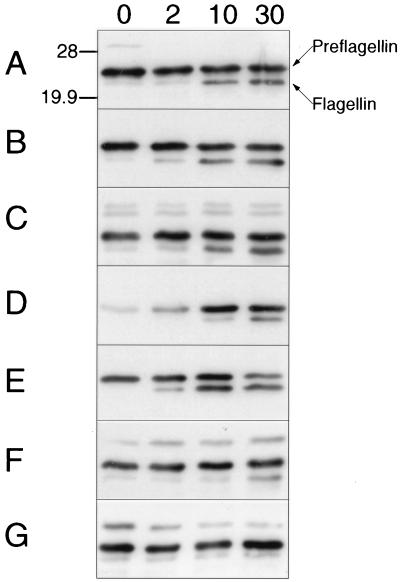

All species of the genus Methanococcus tested (Methanococcus deltae, Methanococcus maripaludis, M. vannielii, M. voltae, M. thermolithotrophicus, and M. jannaschii) exhibited preflagellin peptidase activity against FlaB2 of M. voltae expressed in E. coli, with the sole exception of the hyperthermophile M. igneus (Fig. 4). Interestingly, it is unclear whether the few filamentous structures observed on the surface of M. igneus are, in fact, flagella (6). If M. igneus truly does lack flagella, its lack of preflagellin peptidase activity is readily explained.

FIG. 4.

In vitro processing of M. voltae FlaB2 preflagellin by the preflagellin peptidase of M. voltae and other methanococci. The standard preflagellin peptidase reaction was performed with approximately 72 μg of induced E. coli KJ91 membranes (substrate source) combined with approximately 18 μg of M. voltae membranes (A) in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, at a reaction temperature of 37°C. The same reaction was performed with M. deltae membranes (B), M. maripaludis membranes (C), or M. vannielii membranes (D) in place of M. voltae membranes. The same reaction was performed at a reaction temperature of 60°C with M. thermolithotrophicus membranes (E), M. jannaschii membranes (F), or M. igneus membranes (G) as the enzyme source. Ten-microliter samples were removed at 0, 2, 10, and 30 min and then immediately mixed with 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer and boiled for 5 min; 10-μl aliquots were examined by immunoblotting with a primary antibody dilution of 1:10,000. Positions of 28- and 19.9-kDa molecular mass markers are indicated.

M. thermolithotrophicus demonstrated excellent preflagellin peptidase activity at 60°C (Fig. 4) as well as 37°C (data not shown). Unexpectedly, preflagellin peptidase activity of M. jannaschii was observed at 60 but not at 80°C (data not shown), close to its optimum growth temperature of 85°C. Since M. jannaschii is flagellated at 80°C and thus would be expected to have an active preflagellin peptidase at this temperature, we surmised that the absence of preflagellin peptidase activity at 80°C might be due to the instability of the M. voltae substrate at this elevated temperature. FlaB2 stability was examined by preheating E. coli KJ91 membranes containing FlaB2 for 10 min at 60 or 80°C and subsequently performing an assay for preflagellin peptidase activity with M. voltae membranes at a reaction temperature of 37°C. Peptidase activity was unaffected by the pretreatment at either temperature (data not shown).

We also tested other flagellated methanogens with a wall profile similar to that of the Methanococcus species for the presence of a preflagellin peptidase active against M. voltae FlaB2. Membranes isolated from Methanoculleus marisnigri and Methanogenium cariaci did not cleave the FlaB2 preflagellin of M. voltae under the standard reaction conditions (data not shown). No attempt to detect preflagellin peptidase activity in these methanogens by altering the standard reaction conditions was done.

Direct demonstration of preflagellin processing adds more evidence to the description of archaeal flagellation as a unique motility structure, distinct from that of its bacterial counterpart and with several similarities to type IV pili. Since searches of the complete genome sequences reported for flagellated archaea do not reveal homologs to prepilin peptidases, archaeal preflagellin peptidases may represent a new class of proteolytic enzymes.

Cleavage of the preflagellin leader peptide occurs following an invariant glycine residue in M. voltae and M. vannielii and likely in all other archaeal preflagellins (11). In addition, the −2 and −3 positions in archaeal flagellins are always held by charged amino acids, usually a basic amino acid (lysine or arginine), but in the case of Halobacterium salinarum, glutamic acid is found. Aside from the flagellins, to date the S-layer protein is the only other M. voltae protein with a demonstrated leader peptide. However, the 12-amino-acid leader sequence (MVASALATGVFA) for the S-layer protein (initially reported as an ATPase [7]) has little similarity to the archaeal preflagellin leader peptides, despite the identity in length, and specifically it lacks the conserved glycine at −1. In addition, the leader peptide is not followed by a stretch of hydrophobic amino acids as always found in archaeal flagellins (8) but instead has acidic or basic amino acids in 8 of the first 21 positions of the mature protein. The S-layer gene and protein of Methanothermus fervidus, another flagellated methanogen, have also been studied (5). In this case, the leader peptide has a typical bacterium like leader peptide of 22 amino acids with an Ala-Gly-Ala sequence preceding the cleavage site. This is also very unlike the leader peptides observed in the archaeal flagellins and, again, the conserved −1 glycine is absent. Interestingly, a glucose binding protein in Sulfolobus solfataricus is also produced with an 11-amino-acid leader peptide that is processed at a glycyl-leucyl peptide bond. This leader peptide, as with those of the preflagellins, is also positively charged, which may suggest that this protein is secreted by a similar mechanism (1). However, whether flagellins, S-layer proteins, and other precursors are processed by the same enzyme has yet to be experimentally determined. We would predict, based on the conservation of the amino acids around the cleavage site of the preflagellins in all archaea, that the preflagellin peptidase is a dedicated enzyme for cleavage of preflagellin and perhaps a limited number of related proteins, much as the prepilin peptidase recognizes only prepilin and pseudopilin substrates (17).

Currently, we are generating, by PCR, a family of mutant preflagellins with amino acid substitutions at the conserved positions near the cleavage site. Development and optimization of the preflagellin peptidase assay, as reported in this contribution, will allow us to determine key residues present in the preflagellin that are required for proper processing and should allow the identification of the gene encoding the enzyme responsible for preflagellin peptidase activity in M. voltae.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) awarded to K.F.J.

We thank David C. Jarrell for help in cloning FlaB1 with the His-tag and W. B. Whitman and R. M. Sparling for Methanococcus strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers S-V, Konings W N, Driessen A J M. A unique short signal sequence in membrane-anchored proteins of Archaea. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1595–1596. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayley D P, Florian V, Klein A, Jarrell K F. Flagellin genes of Methanococcus vannielii: amplification by the polymerase chain reaction, demonstration of signal peptides and identification of major components of the flagellar filament. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:639–645. doi: 10.1007/s004380050777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayley D P, Jarrell K F. Overexpression of Methanococcus voltae flagellin subunits in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a source of archaeal preflagellin. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4146–4153. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4146-4153.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayley D P, Jarrell K F. Further evidence to suggest that archaeal flagella are related to bacterial type IV pili. J Mol Evol. 1998;46:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bröckl G, Behr M, Farby S, Hensel R, Kaudewitz H, Biendel E, König H. Analysis and nucleotide sequence of the genes encoding the surface-layer glycoproteins of the hyperthermophilic methanogens Methanothermus fervidus and Methanothermus sociabilis. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burggraf S, Fricke H, Neuner A, Kristjansson J, Rouvier P, Mandelco L, Woese C R, Stetter K O. Methanococcus igneus sp. nov., a novel hyperthermophilic methanogen from a shallow submarine hydrothermal system. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dharmavaram R, Gillevet P, Konisky J. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the vandate-sensitive membrane-associated ATPase of Methanococcus voltae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2131–2133. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2131-2133.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faguy D M, Jarrell K F, Kuzio J, Kalmokoff M L. Molecular analysis of archaeal flagellins: similarity to type IV pilin-transport superfamily widespread in bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:67–71. doi: 10.1139/m94-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarrell K F, Bayley D P, Florian V, Klein A. Isolation and characterization of insertional mutations in flagellin genes in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:657–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5371058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarrell K F, Bayley D P, Kostyukova A S. The archaeal flagellum: a unique motility structure. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5057–5064. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5057-5064.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarrell K F, Correia J D, Thomas N A. Is the processing and translocation system used by flagellins also used by membrane-anchored secretory proteins in archaea? Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:395–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C J, Aizawa S. The bacterial flagellum and flagellar motor: structure, assembly and function. Adv Microb Physiol. 1991;32:109–172. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F. Cloning and sequencing of a multigene family encoding the flagellins of Methanococcus voltae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7113–7125. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7113-7125.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalmokoff M L, Karnauchow T M, Jarrell K F. Conserved N-terminal sequences in the flagellins of archaebacteria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:154–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91744-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalmokoff M L, Koval S F, Jarrell K F. Relatedness of the flagellins from methanogens. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:481–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00276766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nunn D N, Lory S. Components of the protein-excretion apparatus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are processed by the type IV prepilin peptidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:47–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strom M S, Nunn D N, Lory S. Posttranslational processing of type IV prepilin and homologs by PilD of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:527–540. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]