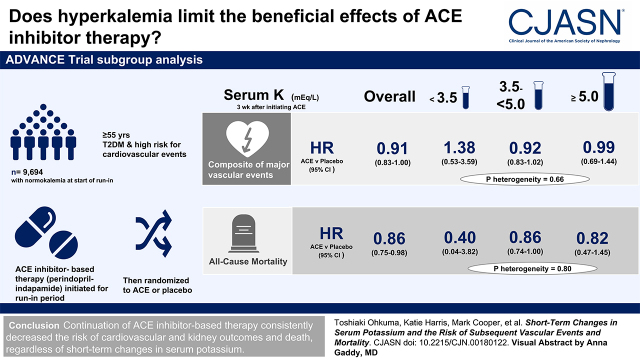

Visual Abstract

Keywords: ACE inhibitors, randomized controlled trials, hyperkalemia, discontinuation, renin angiotensin system

Abstract

Background and objectives

Hyperkalemia after starting renin-angiotensin system inhibitors has been shown to be subsequently associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular and kidney outcomes. However, whether to continue or discontinue the drug after hyperkalemia remains unclear.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Data came from the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial, which included a run-in period where all participants initiated angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–based therapy (a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide). The study population was taken as patients with type 2 diabetes with normokalemia (serum potassium of 3.5 to <5.0 mEq/L) at the start of run-in. Potassium was remeasured 3 weeks later when a total of 9694 participants were classified into hyperkalemia (≥5.0 mEq/L), normokalemia, and hypokalemia (<3.5 mEq/L) groups. After run-in, patients were randomized to continuation of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–based therapy or placebo; major macrovascular, microvascular, and mortality outcomes were analyzed using Cox regression during the following 4.4 years (median).

Results

During active run-in, 556 (6%) participants experienced hyperkalemia. During follow-up, 1505 participants experienced the primary composite outcome of major macrovascular and microvascular events. Randomized treatment of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–based therapy significantly decreased the risk of the primary outcome (38.1 versus 42.0 per 1000 person-years; hazard ratio, 0.91; 95% confidence interval, 0.83 to 1.00; P=0.04) compared with placebo. The magnitude of effects did not differ across subgroups defined by short-term changes in serum potassium during run-in (P for heterogeneity =0.66). Similar consistent treatment effects were also observed for all-cause death, cardiovascular death, major coronary events, major cerebrovascular events, and new or worsening nephropathy (P for heterogeneity ≥0.27).

Conclusions

Continuation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–based therapy consistently decreased the subsequent risk of clinical outcomes, including cardiovascular and kidney outcomes and death, regardless of short-term changes in serum potassium.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number:

Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE), NCT00145925

Introduction

The cardiokidney protective benefits of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade treatment have been established by a number of clinical trials, and the use of RAS inhibitors is now widely recommended for patients at high risk of cardiovascular and kidney diseases, such as CKD (1) and heart failure (2,3). RAS inhibitors are also recommended as a first-line therapy for treatment of hypertension in patients with diabetes, especially those with albuminuria or coronary artery disease, or left ventricular hypertrophy (4,5).

Hyperkalemia is one of the most common and clinically important electrolyte abnormalities as it is a cause of serious arrhythmias that can subsequently result in death (6,7). There are several major risk factors for hyperkalemia, such as kidney dysfunction, diabetes, and adrenal diseases (7). RAS inhibition is also well known as a cause of hyperkalemia (4) due to the inhibition of aldosterone action. Hyperkalemia after starting RAS inhibitors has been shown to be subsequently associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular and kidney outcomes (8). Thus, hyperkalemia is the major barrier to continued prescription of RAS inhibitors (9,10). Underprescription of RAS inhibitors has been reported, especially among high-risk patients with CKD, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure who would be expected to obtain significant benefits from RAS inhibition (9,11,12).

Given the important benefits of cardiokidney protection, stopping RAS blockade therapy in response to hyperkalemia could offset potential clinical benefits in the long term. Previous studies on this issue yielded mixed results. A population-based retrospective cohort study showed that discontinuing RAS inhibitor after hyperkalemia was not associated with a higher risk of subsequent cardiovascular events or all-cause death (13), whereas elevated risks of death or cardiovascular events were observed in the other observational studies (14,15). However, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials to assess the benefits and harms of continuation or discontinuation of RAS inhibitors after hyperkalemia. Hence, whether clinicians should continue or discontinue RAS inhibitors in the setting of hyperkalemia has not yet been clarified.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine the effects of continuation or discontinuation of RAS inhibitor–based therapy after experiencing hyperkalemia on major clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes using data from a large-scale randomized controlled trial: the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

ADVANCE was a factorial randomized controlled trial assessing the effects of BP lowering and intensive blood glucose lowering on vascular complications in type 2 diabetes. Details of the study design have been published previously (16–18). Briefly, a total of 12,877 potentially eligible participants with type 2 diabetes aged ≥55 years at high risk of cardiovascular events (recruited from 215 centers in 20 countries) were registered between 2001 and 2003 and entered a 6-week prerandomization active run-in period, during which all participants received angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor–based therapy (a fixed combination of the ACE inhibitor perindopril [2 mg] and the diuretic indapamide [0.625 mg]). All other treatments were continued at the discretion of the treating physician, with the exception of ACE inhibitors. Participants taking ACE inhibitors other than perindopril withdrew this treatment and were offered substitution with open-label perindopril (2 or 4 mg/d). A total of 11,140 participants who adhered to and tolerated the run-in drug combination of perindopril-indapamide were randomly assigned to a fixed combination of perindopril (2 mg) and indapamide (0.625 mg) or matching placebo. The participants were also allocated to either a gliclazide (modified release)-based intensive glucose-lowering regimen aiming for a hemoglobin A1c ≤6.5% or standard glucose control on the basis of local guidelines. Three months after randomization, the doses of randomized perindopril and indapamide were doubled to 4 and 1.25 mg, respectively. The decision to continue/discontinue randomized treatments was at the discretion of the study participant and the responsible physician. Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the institutional review board of each center. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

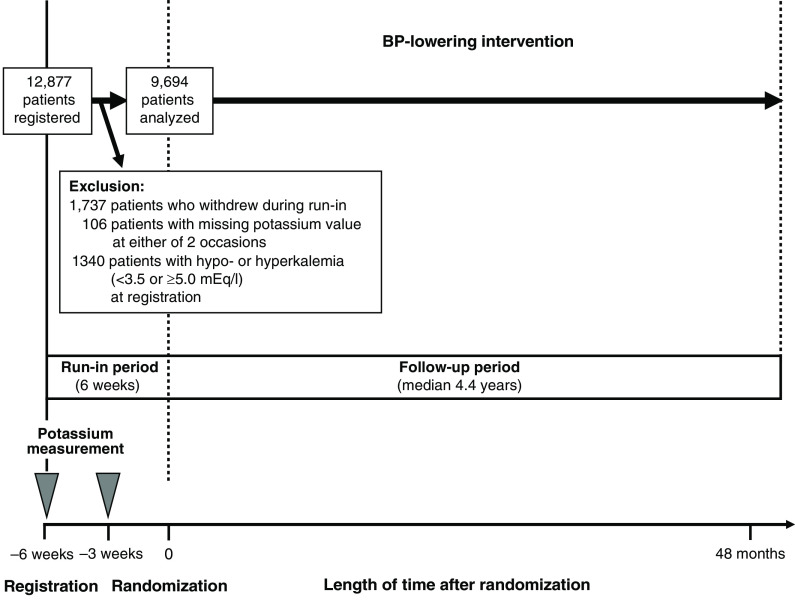

Serum potassium level was measured before and during the active run-in period (3 weeks apart), 4 and 12 months after randomization, at subsequent yearly intervals, and at the end of trial follow-up. Participants with normokalemia (3.5 to <5.0 mEq/L) at the start of the run-in period and with potassium also measured during the run-in period were included in this post hoc analysis of the BP-lowering arm of ADVANCE. There were 178 randomized participants with hypokalemia (<3.5 mEq/L) at registration (mean 3.3 [SD 0.2] mEq/L) and 1162 with hyperkalemia (≥5.0 mEq/L; mean 5.2 [SD 0.3] mEq/L), and 106 had missing serum potassium levels at either registration or −3 weeks (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1). Thus, there were 9694 randomized participants in our study cohort (mean 4.3 [SD 0.3] mEq/L). Short-term changes in serum potassium levels after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy were defined on the basis of the measurements made during the run-in period and classified into hyperkalemia, normokalemia, and hypokalemia.

Figure 1.

Study design and identification of the study cohort. Participants were followed until the earliest of the first study event, death, or the end of follow-up.

Study Outcomes

The primary study outcome of this analysis was the composite of major macrovascular (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) and major microvascular (new or worsening nephropathy or retinopathy) events. Secondary outcomes were all-cause death, cardiovascular death, major macrovascular events, major coronary events (death due to coronary heart disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction), major cerebrovascular events (death due to cerebrovascular disease or nonfatal stroke), major microvascular events, new or worsening nephropathy (defined as the development of macroalbuminuria, doubling of serum creatinine to a level of ≥200 µmol/L, requirement for KRT, or kidney death), and new or worsening retinopathy (development of proliferative retinopathy, macular edema, or diabetes-related blindness or retinal photocoagulation therapy), as previously defined (17). Participants were followed until the earliest of the first study event, death, or the end of follow-up (Figure 1). An independent end point adjudication committee reviewed and validated the outcomes during the randomized treatment period.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are presented as means with SDs for variables approximately symmetrically distributed. Those with skewed distributions are presented as medians with interquartile intervals and were transformed into natural logarithms before statistical analysis. Mean serum potassium values during follow-up were estimated from linear mixed models.

Cox regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for associations between short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy and subsequent risk of outcomes, where short-term changes in serum potassium were considered as hyperkalemia (≥5.0 mEq/L), normokalemia, and hypokalemia (<3.5 mEq/L). Sensitivity analyses using a cutoff value of hyperkalemia of 5.5 mEq/L instead of 5.0 mEq/L or using categories on the basis of thirds of serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy (lowest third: ≤4.10 mEq/L; middle third: 4.11–4.44 mEq/L; highest third: ≥4.45 mEq/L) were also conducted. Additional analyses, including the competing risk of death to yield subdistribution HRs using the methods described by Fine and Gray (19), were also conducted. Adjustments were made for age, sex, region of residence (Asia or other), and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as duration of diabetes mellitus, history of macrovascular diseases, current smoking, current alcohol consumption, body mass index, hemoglobin A1c, total cholesterol, log-transformed triglyceride, systolic BP, eGFR (calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine equation [20]) and log-transformed urine albumin-creatinine ratio at registration, randomized BP-lowering intervention, and randomized glucose control intervention.

The effects of randomized treatment of perindopril-indapamide on outcomes were evaluated by unadjusted Cox regression models according to subgroups on the basis of short-term changes in serum potassium by the intention-to-treat principle. Tests for heterogeneity in the treatment effects across subgroups were performed by adding interaction terms to the relevant models. Potential effect modification for the associations between randomized treatment effects and short-term changes in serum potassium was tested by subsets of participants categorized by eGFR (≥60 and <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and prior RAS inhibitor use at registration. Incidence rates per 1000 person-years by randomized treatment and their differences were estimated from Poisson regression models. The number needed to treat was derived from the inverse of rate differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 7.11 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and R (version 4.1.2; R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Multiple testing of interactions may result in false positives, meaning that with every 20 tests performed, one significant test would be expected with threshold of 5%, even if there were no real effects.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Follow-Up Serum Potassium Levels

Among the 9694 participants with baseline potassium between 3.5 and <5.0 mEq/L who were included in this study, 556 (6%) experienced hyperkalemia (of which five were severe hyperkalemia: potassium ≥6.5 mEq/L), and 99 (1%) experienced hypokalemia 3 weeks after initiating perindopril-indapamide (Table 1). Participants with hyperkalemia were more likely to have longer duration of diabetes, higher levels of systolic BP, higher levels of hemoglobin A1c, higher serum potassium levels, and lower eGFR levels at registration and more likely to take oral hypoglycemic agents, whereas they were less likely to have current alcohol drinking habits and to take calcium-channel blockers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation trial participants with normokalemia at registration according to serum potassium at 3 weeks after the prerandomization active run-in phase

| Variable | Serum Potassium at 3 wk after Initiating Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme–Based Therapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypokalemia, <3.5 mEq/L | Normokalemia, 3.5–5.0 mEq/L | Hyperkalemia, ≥5.0 mEq/L | |

| No. of participants | 99 | 9039 | 556 |

| Demographic factors | |||

| Age, yr | 65 (7) | 66 (6) | 66 (6) |

| Women, n (%) | 37 (37) | 3868 (43) | 244 (44) |

| Residence in Asia, n (%) | 50 (51) | 3362 (37) | 212 (38) |

| Medical and lifestyle history | |||

| Duration of diabetes mellitus, yr | 6.8 (6.1) | 7.8 (6.2) | 9.0 (7.0) |

| History of macrovascular disease at baseline, n (%) | 32 (32) | 2873 (32) | 173 (31) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 16 (16) | 1396 (15) | 81 (15) |

| Current alcohol drinking, n (%) | 32 (32) | 2799 (31) | 147 (26) |

| Risk factors | |||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 145 (23) | 145 (21) | 147 (22) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 83 (12) | 81 (11) | 81 (11) |

| HbA1c, % | 7.2 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.6) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 204 (52) | 201 (46) | 203 (48) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 147 (106–202) | 142 (106–204) | 151 (106–213) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.3 (3.8) | 28.4 (5.2) | 28.2 (5.2) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 75 (18) | 75 (17) | 70 (19) |

| Decreased eGFR (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), % | 21 (21) | 1,772 (20) | 158 (28) |

| UACR, mg/g | 18 (10–70) | 14 (7–37) | 18 (9–65) |

| Randomized treatments, n (%) | |||

| Perindopril-indapamide | 45 (45) | 4511 (50) | 292 (53) |

| Intensive blood glucose control | 56 (57) | 4536 (50) | 266 (48) |

| Blood glucose–lowering treatments, n (%) | |||

| Oral hypoglycemic agentsa | 85 (86) | 8186 (91) | 520 (94) |

| Insulin | 0 (0) | 132 (1) | 11 (2) |

| BP-lowering treatments, n (%) | |||

| β-blocker | 29 (29) | 2156 (24) | 154 (28) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 36 (36) | 2803 (31) | 139 (25) |

| Diureticsb | 33 (33) | 2078 (23) | 142 (26) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitorsb | 49 (49) | 3789 (42) | 250 (45) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 2 (2) | 489 (5) | 37 (7) |

| Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors | 51 (52) | 4209 (47) | 281 (51) |

| Other antihypertensive agents | 22 (22) | 1099 (12) | 72 (13) |

| Any BP-lowering agentsb | 86 (87) | 6721 (74) | 421 (76) |

| Changes in serum potassium, mEq/L | |||

| Potassium at registration | 3.80 (3.60–4.10) | 4.30 (4.04–4.50) | 4.60 (4.30–4.80) |

| Potassium after 3 wk during the run-in period | 3.35 (3.20–3.40) | 4.25 (4.00–4.50) | 5.10 (5.00–5.29) |

For continuous variables, mean values and their corresponding SDs are presented, except that median values (interquartile intervals) are presented for triglycerides, UACR, and potassium. Categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors were defined as either angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; UACR, urine albumin-creatinine ratio.

Randomized treatment with gliclazide was not included.

Randomized treatment with perindopril-indapamide was not included.

Although serum potassium levels increased sharply during the first 3 weeks after administration of perindopril-indapamide among patients experiencing hyperkalemia, serum potassium had returned to broadly the same levels as those before administration by 4 months postrandomization and plateaued thereafter (Supplemental Figure 1A). The opposite trends were observed among patients with hypokalemia. Serum potassium levels during follow-up were 4.62 (SEM 0.01) mEq/L, 4.33 (SEM 0.003) mEq/L, and 3.97 (SEM 0.04) mEq/L in participants with hyperkalemia, normokalemia, and hypokalemia, respectively. Follow-up potassium values among each subgroup did not show substantial differences, regardless of randomized BP-lowering treatment (Supplemental Figure 1B).

Associations between Short-Term Changes in Serum Potassium after Initiating Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor–Based Therapy and Subsequent Risk of Clinical Outcomes

During a median follow-up of 4.4 years, 1505 participants experienced the composite outcome of major macrovascular and microvascular events. A total of 727 died, 376 experienced cardiovascular death, 827 experienced major macrovascular events, 453 experienced major coronary events, 366 experienced major cerebrovascular events, 768 experienced major microvascular events, 322 experienced new or worsening nephropathy, and 489 experienced new or worsening retinopathy.

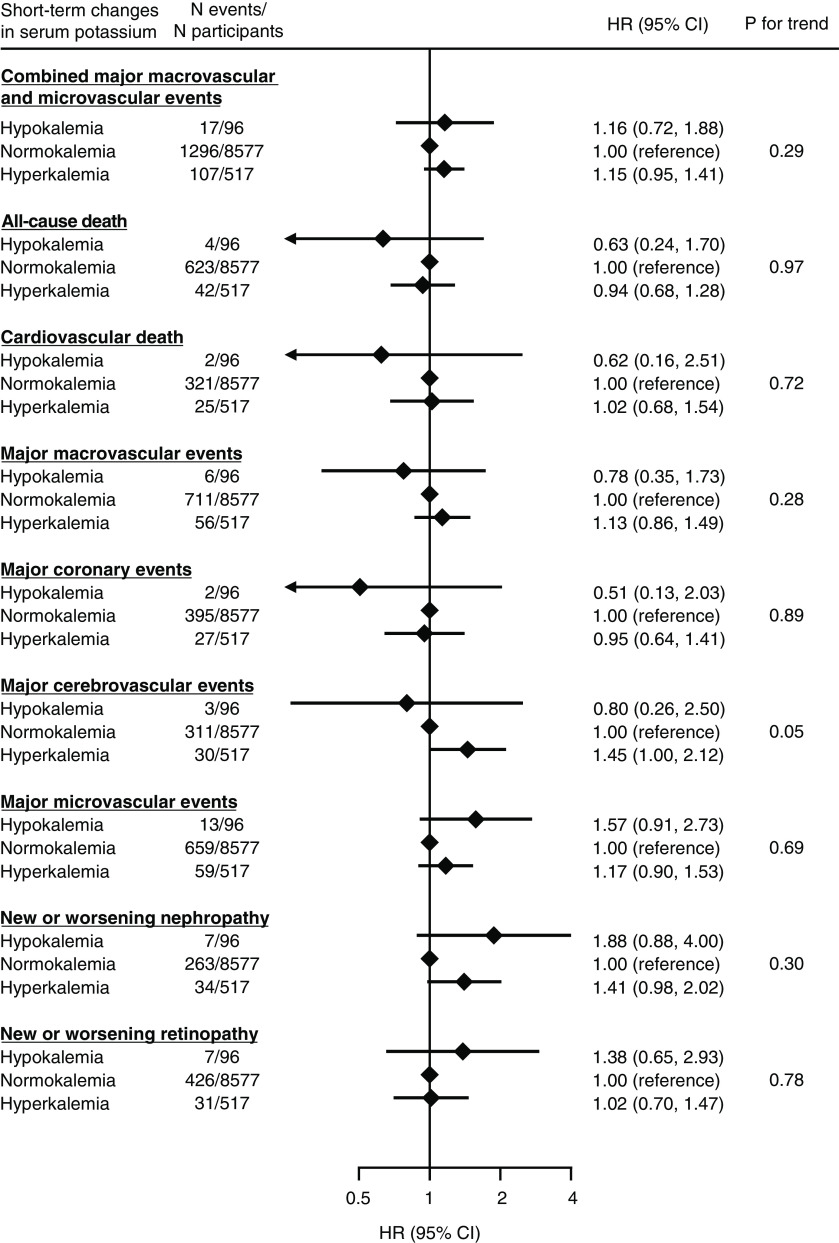

Hyperkalemia after initiation of perindopril-indapamide was associated with a higher risk of a composite of major macrovascular and microvascular events, with a multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI) of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.95 to 1.41) compared with normokalemia, although it was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Similarly, hypokalemia was also in the direction of elevation in the risk of the outcome (adjusted HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.88). Similar higher, but not statistically significant, risks of the outcomes were observed for hyperkalemia with major macrovascular events, major cerebrovascular events, major microvascular events, and new or worsening nephropathy. Hypokalemia showed a nonsignificant but lower risk of all-cause death, cardiovascular death, major macrovascular events, major coronary events, and major cerebrovascular events. Results from the analyses that changed a threshold of hyperkalemia from 5.0 to 5.5 mEq/L or the competing risk models showed broadly similar results (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Most of the associations were attenuated when sensitivity analyses were conducted by using thirds of serum potassium after treatment initiation (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The association between short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor–based therapy and subsequent risk of major clinical outcomes. Short-term changes in serum potassium were defined on the basis of the measurement made 3 weeks after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy. Models were adjusted for age, sex, region of residence, duration of diabetes mellitus, history of macrovascular diseases, smoking habit, alcohol drinking habit, body mass index, hemoglobin A1c, total cholesterol, log-transformed triglyceride, systolic BP, eGFR, log-transformed urine albumin-creatinine ratio, randomized BP-lowering intervention, and randomized glucose control intervention (n=9190). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Randomized Treatment Effects of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor–Based Therapy According to Short-Term Changes in Serum Potassium

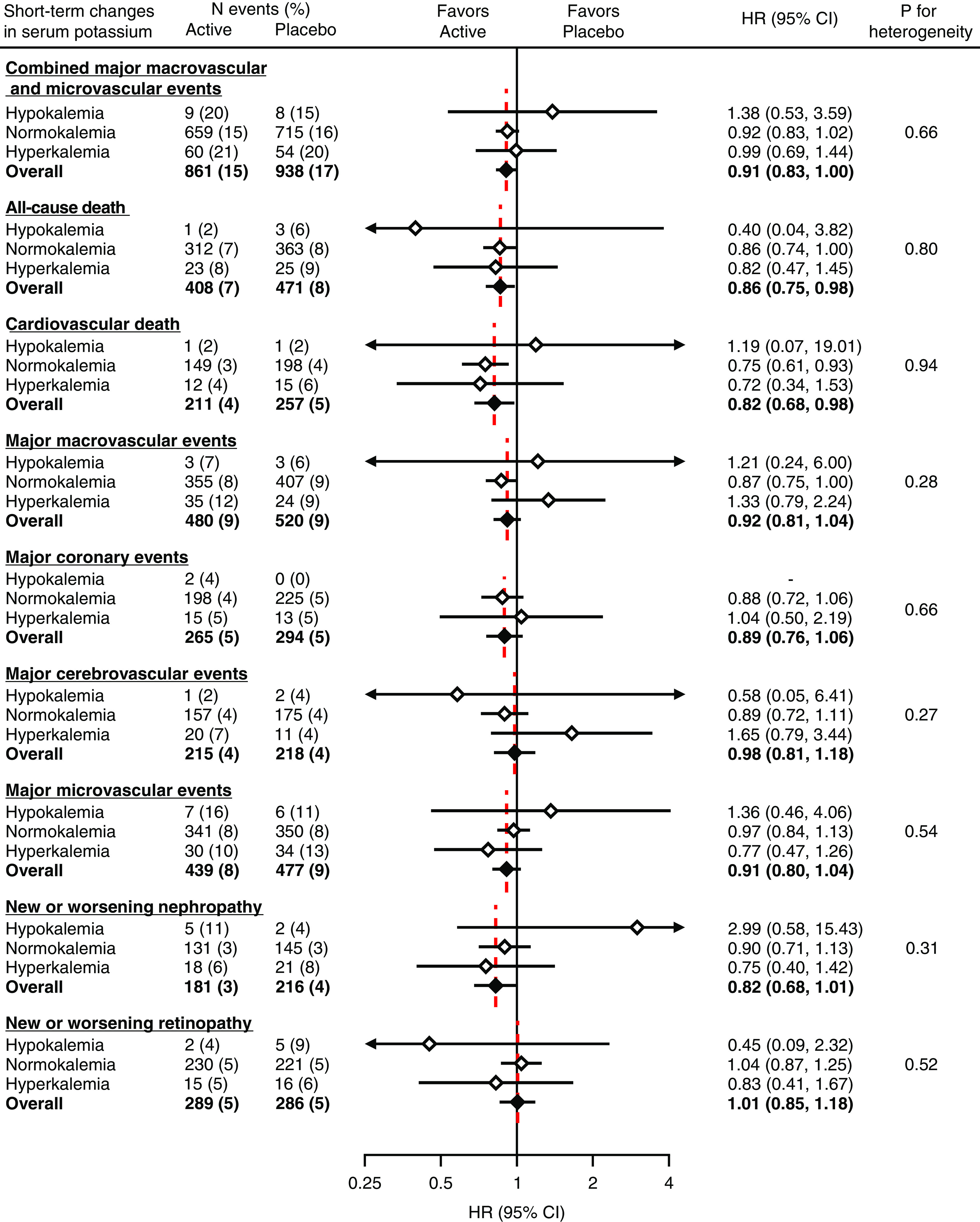

Overall, randomized treatment of perindopril-indapamide significantly decreased the primary composite outcome by 9% (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.00; P=0.04) compared with placebo (Figure 3). The HRs were 0.99 (95% CI, 0.69 to 1.44) in participants with hyperkalemia, 0.92 (95% CI, 0.83 to 1.02) in those with normokalemia, and 1.38 (95% CI, 0.53 to 3.59) in those with hypokalemia, with no statistically significant heterogeneity (P=0.66). The effects of perindopril-indapamide did not differ significantly across subgroups defined by eGFR or use of RAS inhibitors at registration (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Modification of randomized treatment effects of ACE inhibitor–based therapy on the risk of major clinical outcomes according to short-term changes in serum potassium after treatment initiation. Short-term changes in serum potassium were defined on the basis of the measurement made 3 weeks after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy. White diamonds indicate the HRs for subgroups defined by short-term change in serum potassium. Black diamonds indicate the HRs of overall randomized participants of the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation trial (n=11,140). Active indicates perindopril-indapamide.

Perindopril-indapamide treatment was also associated with significant decreases in the risk of all-cause death (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75 to 0.98) and cardiovascular death (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.98), with consistent effects across subgroups (P for heterogeneity =0.80 and 0.94, respectively). The corresponding overall HRs for major macrovascular events, major coronary events, major cerebrovascular events, major microvascular events, new or worsening nephropathy, and new or worsening retinopathy were 0.92 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.04), 0.89 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.06), 0.98 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.18), 0.91 (95% CI, 0.80 to 1.04), 0.82 (95% CI, 0.68 to 1.01), and 1.01 (95% CI, 0.85 to 1.18), respectively. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the treatment effects across subgroups for these outcomes (P for heterogeneity ≥0.27) (Figure 3). These consistent treatment effects did not change significantly when linear trends across subgroups were examined (P for trend ≥0.10). Additional analyses using a cutoff value of hyperkalemia of 5.5 mEq/L instead of 5.0 mEq/L or accounting for competing risk of death showed similar results (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Sensitivity analyses by thirds of serum potassium after treatment initiation did not materially change the results, with the exception of nephropathy (Supplemental Figure 4). The absolute benefits associated with perindopril-indapamide treatment tended to be greater in participants with hyperkalemia compared with those with normokalemia, especially for all-cause and cardiovascular death, major microvascular events, new or worsening nephropathy, and new or worsening retinopathy, whereas no such effects were observed for the other outcomes (Supplemental Table 6). The number needed to treat to prevent one death over 5 years was 51 for those with hyperkalemia and 75 for those with normokalemia. The corresponding values were 52 and 78 for cardiovascular death, 27 and 385 for major microvascular events, 42 and 262 for new or worsening nephropathy, and 80 and −421 for new or worsening retinopathy.

Discussion

This analysis from a large-scale randomized controlled trial, which examined the effects of ACE inhibitor–based therapy, showed that hyperkalemia after initiation of perindopril-indapamide treatment demonstrated estimates in the direction of higher subsequent risk of vascular events. However, the benefits of continuation of perindopril-indapamide on major clinical outcomes, including vascular events, all-cause death, and cardiovascular death, were similar, irrespective of short-term changes in serum potassium. Overall, our results suggest that, even in patients who experience ACE inhibitor–induced hyperkalemia, the benefits of continuation of the drug outweigh the potential risks.

RAS inhibitors were widely recommended as a first-line antihypertensive therapy among patients with CKD (1), heart failure (2), and diabetes with albuminuria or coronary artery disease (4). However, underutilization of the drug has been identified by previous studies (9,12,21,22), where hyperkalemia constitutes a major reason (9,23). Hyperkalemia following RAS inhibitors initiation was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular (8) and kidney outcomes (8,24) and death (8), which raises concerns of whether to continue or stop RAS inhibitors after hyperkalemia. Current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines recommend monitoring of changes in serum potassium within 2–4 weeks of initiation of RAS inhibitors and discontinuation or dose titration if hyperkalemia persists despite appropriate medical treatment (25). However, the evidence that supports the continuation of the drug following hyperkalemia for cardiokidney protection has been scarce. Regarding this issue, in a population-based cohort study of older adults who experienced RAS inhibitors–related hyperkalemia, the subsequent risk of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause death within 1 year did not differ significantly between continuation at the same dose and discontinuation of RAS inhibitors, which indicates no apparent elevation in the risk of cardiovascular events and death after discontinuation of the drug (13). Conversely, the other observational studies among patients undergoing routine care (14) or those with CKD (15) showed that discontinuation of RAS inhibitors after hyperkalemia was associated with a higher risk of death and cardiovascular events. However, it should be noted that these studies were limited by an observational study design and so, a cause and effect relationship cannot be inferred.

The present findings from a randomized trial of ACE inhibitors–based therapy showed, for the first time, that continued use of the drug consistently decreased the risk of major clinical outcomes, including vascular events and all-cause and cardiovascular death, regardless of the increase or decrease in serum potassium after initiation. In other words, withdrawal of the drug after hyperkalemia was associated with a higher risk of mortality and vascular events, which supports the clinical decision to continue RAS inhibitors even if serum potassium rises after administration. That is to say that more attention should be paid when deciding on drug discontinuation because unnecessary stopping may lead to undesirable long-term consequences (26). However, careful monitoring and management of serum potassium are necessary when deciding to continue the drug, particularly in patients at high risk of hyperkalemia, such as those with lower kidney function or borderline high serum potassium levels (4,25). Although mild to moderate hyperkalemia can be managed by measures to decrease serum potassium levels (25), clinicians should always keep in mind that severe hyperkalemia, such as ≥6.5 mEq/L or any elevation with any manifestations of hyperkalemia (27), is a clinical emergency with a high risk of life-threatening arrhythmias and deaths, and it must be treated immediately by intravenous administration of calcium gluconate, sodium bicarbonate, and insulin with glucose (6).

The strengths of our study include the large and diverse group of participants enrolled from 20 countries from Europe, Asia, Australasia, and North America and a long duration of follow-up with rigorous adjudication of the outcomes. In addition, this is the first study that assessed the randomized treatment effects of continued use of ACE inhibitor–based therapy following hyperkalemia using the data from a randomized trial, whereas a prior study on this topic was observational. However, some limitations should be mentioned. First, the participants of this study were patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular diseases who were included in a clinical trial. Therefore, the findings might not be applicable to broader general patients with diabetes. However, baseline characteristics of the participants included in the ADVANCE trial were similar to those with diabetes in the community (28). Second, among patients who experienced hyperkalemia (n=556; 6% of overall participants of this analyses), the number of patients with serum potassium levels ≥6.0 mEq/L was limited (n=12; 0.12%). This may be attributable to randomized treatment consisting of a combination of the ACE inhibitor, perindopril, and the diuretic indapamide. As the latter has hypokalemic effects, the observed effects on serum potassium and clinical outcomes may be partially due to the diuretic. Third, we did not have information on the other drugs that can cause hyperkalemia, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and the management of hyperkalemia. Fourth, there were two participants who permanently discontinued randomized treatment due to hyperkalemia among 25 of those who reported serious adverse events with hyperkalemia (no deaths attributable to hyperkalemia), and thus, we cannot deny the possibility that these discontinuations affected the observed findings. However, the randomized treatment effects of perindopril-indapamide on outcomes were evaluated by Cox regression models on the basis of the intention-to-treat principle. Therefore, the observed effects are likely to be more conservative and bias the results to the null hypothesis of no effects compared with per protocol analyses considering discontinuation. Fifth, exclusion of participants (9694 participants of 12,877 potentially eligible participants were included) may also limit the generalizability of the findings to broader diabetic patients. Finally, this study was a post hoc analysis of the ADVANCE trial, which was conducted in the early 2000s and not primarily designed to investigate treatment effects in subgroups defined by changes in serum potassium; there may be limited power to identify heterogeneity with small numbers with hypo- or hyperkalemia. Although sensitivity analyses using the categories defined by thirds of change in serum potassium showed almost similar results, these findings should be recognized as hypothesis generating. Future randomized trials originally designed to elucidate benefits and harms associated with the continuation of RAS inhibitors after hyperkalemia or collaborative meta-analyses of existing trials are needed to validate these findings.

In conclusion, hyperkalemia after initiation of perindopril-indapamide may demonstrate potential for a higher risk of vascular events. However, continuation of the drug consistently decreased subsequent risk of the clinical outcomes, including vascular events and death, regardless of changes in serum potassium. These findings suggest that discontinuation of RAS inhibitor–based therapy after hyperkalemia may diminish the benefits in terms of reduction in the long-term risk of vascular events and death, although close attention to severe hyperkalemia, which can cause life-threatening arrhythmias, is needed. Additional interventional studies will be required to confirm this hypothesis.

Disclosures

J. Chalmers reports employment with The George Institute for Global Health and research grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and from Servier for the ADVANCE trial and the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and DiamicronModified Release Controlled Evaluation Observational (ADVANCE-ON) post-trial follow-up study. M. Cooper reports consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and NovoNordisk; honoraria from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim; and serving in an advisory or leadership role for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and MSD. M. Cooper reports grants from Novo Nordisk, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Merck, Novartis, and Servier outside the submitted work. D.E. Grobbee reports consultancy agreements with and honoraria from Vifor. P. Hamet reports employment with Center Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, ownership interest in Optithera et Medpharmgene (stock but no revenue), patents, consulting fees from Servier, and grant support from Quebec Cosortium for Drug Discovery (CQDM) and Servier. S. Harrap reports grants from The George Institute for Global Health during the conduct of the study and other from Servier outside the submitted work. G. Mancia reports honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Gentili, Medtronic, Menarini, Merck, Novartis, Recordati, Sandoz, Sanofi, Servier, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. M. Marre reports consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Novo Nordisk; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Novo Nordisk; personal fees from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier; and grant support from Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. A. Patel reports employment with The George Institute for Global Health, which is the majority shareholder of George Health Enterprises that has received investment funds to develop fixed-dose combination medicines. A. Patel reports serving as a board member of The George Institute India (nonprofit) and reports grants from Servier during the conduct of the study. A. Rodgers reports employment with The George Institute, sits on a data and safety monitoring board for Idorsia, and reports honoraria from Idorsia. A. Rodgers is one of the inventors on several patents filed by The George Institute for Global Health on compositions for the treatment of hypertension. None of the inventors have a financial interest in these planned products. He is seconded to work for George Health Enterprises (the social enterprise arm of The George Institute for Global Health). He has received investment to develop fixed-dose combination products containing aspirin, statin, and BP-lowering drugs. B. Williams reports honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Daichi Sankyo, Novartis, Pfizer, and Servier; serving as the secretary of the International Society of Hypertension and as a University College London Hospitals (NHS) Executive Board member; and other interests or relationships as a member of council of the European Society of Hypertension and the secretary of the International Society of Hypertension. M. Woodward reports employment with The George Institute for Global Health and consultancy agreements with Amgen, Freeline, and Kyowa Kirin. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The ADVANCE trial was funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (project grant ID 211086 and programme grant IDs 358395 and 571281) and from Servier. J. Chalmers and M. Woodward are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia program grant APP1149987. M. Woodward is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia investigator grant APP1174120.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Calamari, Hyperkalemia, and Renin-Angiotensin System Blockade,” on pages 1116–1118.

Author Contributions

T. Ohkuma, J. Chalmers, and M. Woodward conceptualized the study; T. Ohkuma and K. Harris were responsible for formal analysis; J. Chalmers and M. Woodward were responsible for funding acquisition; J. Chalmers and M. Woodward provided supervision; T. Ohkuma wrote the original draft; and J. Chalmers, M. Cooper, D.E. Grobbee, P. Hamet, S. Harrap, K. Harris, G. Mancia, M. Marre, A. Patel, A. Rodgers, B. Williams, and M. Woodward reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its supplemental material. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00180122/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the ADVANCE trial participants according to serum potassium at registration.

Supplemental Table 2. Sensitivity analyses: the association between short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy and subsequent risk of major clinical outcomes using a cutoff value of hyperkalemia of 5.5 mEq/L instead of 5.0 mEq/L.

Supplemental Table 3. Competing risk analysis: the association between short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy and subsequent risk of major clinical outcomes accounting for the competing risk of death.

Supplemental Table 4. Sensitivity analyses: modification of randomized treatment effects of ACE inhibitor–based therapy on the risk of major clinical outcomes by short-term changes in serum potassium after treatment initiation using a cutoff value of hyperkalemia of 5.5 mEq/L instead of 5.0 mEq/L.

Supplemental Table 5. Competing risk analysis: modification of randomized treatment effects of ACE inhibitor–based therapy on the risk of major clinical outcomes by short-term changes in serum potassium after treatment initiation accounting for the competing risk of death.

Supplemental Table 6. Rate reductions for major clinical outcomes according to short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy.

Supplemental Figure 1. Mean serum potassium according to short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy.

Supplemental Figure 2. Sensitivity analyses: the association between short-term changes in serum potassium after initiating ACE inhibitor–based therapy and subsequent risk of major clinical outcomes according to thirds of serum potassium after treatment initiation.

Supplemental Figure 3. Subgroup analyses: modification of randomized treatment effects of ACE inhibitor–based therapy on the risk of the composite of major macrovascular and microvascular events according to short-term changes in serum potassium after treatment initiation stratified by eGFR level at registration and RASI use at registration.

Supplemental Figure 4. Sensitivity analyses: modification of randomized treatment effects of ACE inhibitor–based therapy on the risk of major clinical outcomes by thirds of serum potassium after treatment initiation.

References

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Blood Pressure Work Group : KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Available at: https://kdigo.org/guidelines/blood-pressure-in-ckd/. Accessed June 11, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; ESC Scientific Document Group : 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 37: 2129–2200, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C: 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 136: e137–e161, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association : Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 44[Suppl 1]: S1–S2, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, Huikuri HV, Johansson I, Jüni P, Lettino M, Marx N, Mellbin LG, Östgren CJ, Rocca B, Roffi M, Sattar N, Seferović PM, Sousa-Uva M, Valensi P, Wheeler DC; ESC Scientific Document Group : 2019 ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J 41: 255–323, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovesdy CP: Management of hyperkalemia: An update for the internist. Am J Med 128: 1281–1287, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter RW, Bailey MA: Hyperkalemia: Pathophysiology, risk factors and consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34[Suppl 3]: iii2–iii11, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heerspink HJ, Gao P, de Zeeuw D, Clase C, Dagenais GR, Sleight P, Lonn E, Teo KT, Yusuf S, Mann JF: The effect of ramipril and telmisartan on serum potassium and its association with cardiovascular and renal events: Results from the ONTARGET trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 21: 299–309, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein M: Hyperkalemia constitutes a constraint for implementing renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibition: The widening gap between mandated treatment guidelines and the real-world clinical arena. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 6: 20–28, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linde C, Bakhai A, Furuland H, Evans M, McEwan P, Ayoubkhani D, Qin L: Real-world associations of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor dose, hyperkalemia, and adverse clinical outcomes in a cohort of patients with new-onset chronic kidney disease or heart failure in the United Kingdom. J Am Heart Assoc 8: e012655, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy DP, Drawz PE, Foley RN: Trends in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker use among those with impaired kidney function in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1314–1321, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maggioni AP, Anker SD, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, Ponikowski P, Zannad F, Amir O, Chioncel O, Leiro MC, Drozdz J, Erglis A, Fazlibegovic E, Fonseca C, Fruhwald F, Gatzov P, Goncalvesova E, Hassanein M, Hradec J, Kavoliuniene A, Lainscak M, Logeart D, Merkely B, Metra M, Persson H, Seferovic P, Temizhan A, Tousoulis D, Tavazzi L; Heart Failure Association of the ESC : Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12,440 patients of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 15: 1173–1184, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hundemer GL, Talarico R, Tangri N, Leon SJ, Bota SE, Rhodes E, Knoll GA, Sood MM: Ambulatory treatments for RAAS inhibitor-related hyperkalemia and the 1-year risk of recurrence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 365–373, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, Fu EL, Trevisan M, Jernberg T, Sjölander A, Clase CM, Carrero JJ: Stopping renin-angiotensin system inhibitors after hyperkalemia and risk of adverse outcomes. Am Heart J 243: 177–186, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leon SJ, Whitlock R, Rigatto C, Komenda P, Bohm C, Sucha E, Bota SE, Tuna M, Collister D, Sood M, Tangri N: Hyperkalemia-related discontinuation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and clinical outcomes in CKD: A population-based cohort study [published online ahead of print January 25, 2022]. Am J Kidney Dis 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ADVANCE Management Committee : Study rationale and design of ADVANCE: Action in diabetes and vascular disease--preterax and diamicron MR controlled evaluation. Diabetologia 44: 1118–1120, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, Harrap S, Poulter N, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee DE, Hamet P, Heller S, Liu LS, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan CY, Rodgers A, Williams B; ADVANCE Collaborative Group : Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370: 829–840, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, Liu L, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan C, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, Bompoint S, de Galan BE, Joshi R, Travert F; ADVANCE Collaborative Group : Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358: 2560–2572, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirazian S, Grant CD, Mujeeb S, Sharif S, Kumari P, Bhagat M, Mattana J: Underprescription of renin-angiotensin system blockers in moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Am J Med Sci 349: 510–515, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy IE, Han J, Montez-Rath ME, Chertow GM: Barriers to ACEI/ARB use in proteinuric chronic kidney disease: An observational study. Mayo Clin Proc 96: 2114–2122, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnier M: Renin-angiotensin system blockade in advanced kidney disease: Stop or continue? Kidney Med 2: 231–234, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miao Y, Dobre D, Heerspink HJ, Brenner BM, Cooper ME, Parving HH, Shahinfar S, Grobbee D, de Zeeuw D: Increased serum potassium affects renal outcomes: A post hoc analysis of the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) trial. Diabetologia 54: 44–50, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Diabetes Work Group : KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Available at: https://kdigo.org/guidelines/diabetes-ckd/. Accessed June 11, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohkuma T, Jun M, Rodgers A, Cooper ME, Glasziou P, Hamet P, Harrap S, Mancia G, Marre M, Neal B, Perkovic V, Poulter N, Williams B, Zoungas S, Chalmers J, Woodward M; ADVANCE Collaborative Group : Acute increases in serum creatinine after starting angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-based therapy and effects of its continuation on major clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertension 73: 84–91, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rafique Z, Chouihed T, Mebazaa A, Frank Peacock W: Current treatment and unmet needs of hyperkalaemia in the emergency department. Eur Heart J Suppl 21[Suppl A]: A12–A19, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalmers J, Arima H: Importance of blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: Focus on ADVANCE. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 55: 340–347, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.