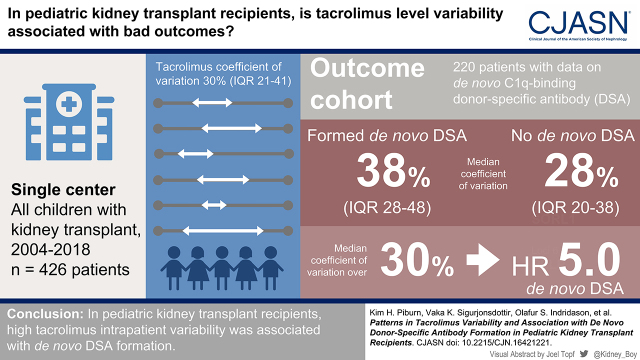

Visual Abstract

Keywords: pediatric kidney transplantation, tacrolimus, young adult, kidney transplantation, child, immunosuppression, transplant outcomes

Abstract

Background and objectives

High tacrolimus intrapatient variability has been associated with inferior graft outcomes in patients with kidney transplants. We studied baseline patterns of tacrolimus intrapatient variability in pediatric patients with kidney transplants and examined these patterns in relation to C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibodies.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

All tacrolimus levels in participants who underwent kidney-only transplantation at a single pediatric center from 2004 to 2018 (with at least 12-month follow-up, followed until 2019) were analyzed to determine baseline variability. Intrapatient variability was defined using the coefficient of variation (SD/mean ×100%) of all samples in a 6-month moving window. Routine de novo donor-specific antibody measurements were available for a subgroup of patients transplanted in 2010–2018. Cox proportional hazards models using tacrolimus intrapatient variability as a time-varying variable were used to examine the association between intrapatient variability and graft outcomes. The primary outcome of interest was C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibody formation.

Results

Tacrolimus intrapatient variability developed a steady-state baseline of 30% at 10 months post-transplant in 426 patients with a combined 31,125 tacrolimus levels. Included in the outcomes study were 220 patients, of whom 51 developed C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibodies. De novo donor-specific antibody formers had higher intrapatient variability, with a median of 38% (interquartile range, 28%–48%) compared with 28% (interquartile range, 20%–38%) for nondonor-specific antibody formers (P<0.001). Patients with high tacrolimus intrapatient variability (coefficient of variation >30%) had higher risk of de novo donor-specific antibody formation (hazard ratio, 5.35; 95% confidence interval, 2.45 to 11.68). Patients in the top quartile of tacrolimus intrapatient variability (coefficient of variation >41%) had the strongest association with C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibody formation (hazard ratio, 11.81; 95% confidence interval, 4.76 to 29.27).

Conclusions

High tacrolimus intrapatient variability was strongly associated with de novo donor-specific antibody formation.

Introduction

Kidney transplantation is the most effective treatment for children with kidney failure, although long-term graft survival still remains limited by rejection (1,2). Patients with kidney transplants require immunosuppression to maintain the function of their grafts, almost universally with the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus (3). Given its narrow therapeutic index, tacrolimus requires frequent drug-level monitoring, most commonly with tacrolimus trough blood levels (4,5), but studies have been conflicting on whether tacrolimus trough levels are predictive of graft outcomes (6–8). In recent years, tacrolimus intrapatient variability has emerged as a novel method for tacrolimus monitoring. Intrapatient variability reflects the fluctuation in trough levels within an individual over a given time interval (9). Fluctuations in tacrolimus levels may occur for many reasons, including vomiting or feeding problems, dose adjustments in response to infection or malignancy, timing and fat content of meals, drug-drug interactions or genetic factors that affect its metabolism, and medication nonadherence (9–11).

Studies in adults strongly suggest that highly variable tacrolimus levels are associated with poor long-term outcomes in kidney transplant recipients (12–16). Several studies in pediatric patients with kidney transplants have also reported this association between high intrapatient variability and poor graft outcomes (8,17–20). However, baseline patterns of tacrolimus intrapatient variability in pediatric patients with kidney transplants have not been well described in the literature.

The objectives of this study were to first characterize a baseline pattern of tacrolimus intrapatient variability in pediatric patients with kidney transplants and then investigate the risk threshold for tacrolimus intrapatient variability in relation to graft outcomes. We hypothesize that high intrapatient variability may reflect periods of insufficient immunosuppression and lead to de novo donor-specific antibody (DSA) formation. Measuring high intrapatient variability may be a useful tool to detect nonadherence in pediatric patients with kidney transplants, thus directing interventions to prolong graft survival.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University (protocol no. 54691).

Study Population

All patients who received a kidney-only transplant at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford from January 1, 2004 to March 1, 2018 were considered for inclusion in the study. Patients were identified from the electronic health record (EHR) by kidney transplant status diagnosis code and transplant date of 2004 or later; all available serum tacrolimus levels for these patients were obtained from our clinical data warehouse by a clinical analyst. Patients with <12 months of follow-up or with fewer than two tacrolimus levels were excluded. Data were retrospectively collected from the EHR. If a patient received more than one transplant during the study period, only data on the first allograft were used in the outcome analyses. Patients were followed until the earliest of the following end points: end of the study period (March 1, 2019), graft loss, or the patient’s 25th birthday (the age when our center transitions patients to adult care). Maintenance immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for all patients with or without prednisone on the basis of immunologic risk. Target tacrolimus trough levels are displayed in Supplemental Table 1.

First, we analyzed baseline patterns of tacrolimus intrapatient variability on the basis of age at transplantation and post-transplant follow-up time. We then identified a subgroup of patients who received their first kidney transplant after 2010 when de novo DSA screening became standardized at our center and analyzed their outcomes. The inclusion criteria were the same as above; patients with inconclusive DSA data were excluded. This cohort was transplanted from January 1, 2010 to March 1, 2018 and will be referred as the outcome cohort hereafter. Patient characteristics, such as sex, age at transplantation, transplant date, donor source, HLA matching, and historical peak panel reactive antibody, were obtained from the EHR.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Tacrolimus, De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody Formation, and Outcomes of Interest

We collected and analyzed all available tacrolimus levels independent of tacrolimus formulation, clinical setting at the time of blood collection, or laboratory testing methods. Our cohort received testing at multiple laboratories, with many patients often getting blood drawn at more than one laboratory per patient preference and insurance coverage demands. The assays used for tacrolimus monitoring included those run by Stanford Lab (immunoassay) (21), Quest Diagnostics (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) (22), and LabCorp (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) (23), whereas a variety of assays were in use at other community and hospital laboratories. Intrapatient variability of tacrolimus was quantified by calculating the coefficient of variation (σ/μ×100%) over the immediate 6-month period (i.e., retrospective moving window) prior to each tacrolimus level.

In the outcome cohort, all patients were tested for de novo DSA at the time of transplant, on surveillance screening, and as clinically indicated (Supplemental Table 2). The presence of C1q-binding and anti-HLA class 2 de novo DSAs was determined using a single-antigen flow bead assay per the manufacturer’s protocol (C1qScreen; One Lambda Inc.) or a solid-phase assay, respectively, on a Luminex platform analyzed by the Fusion software, and it was interpreted using normalized mean fluorescence intensity values. A positive reaction was defined by a cutoff of >1000 mean fluorescence intensity, which is also our institutional positivity threshold (24). The primary outcome of interest was C1q-binding de novo DSA formation defined as DSAs identified at any point after transplantation that did not exist pretransplant because in a study by our group, de novo C1q-binding DSAs that persisted were found to be the strongest independent risk factor for graft failure (hazard ratio [HR], 45.5; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 11.7 to 177.4) (25). Secondary outcomes included development of anti-HLA class 2 de novo DSAs, proteinuria with urine protein-creatinine ratio of ≥0.5 mg/mg for ≥3 months, decline in eGFR to <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 that persisted for ≥3 months, and graft loss defined as return to dialysis or preemptive retransplantation. These variables were readily available for each patient in the EHR given the close follow-up required at our center, including required de novo DSA screening, serum chemistries and urinalyses, and mandatory documentation of any graft loss to the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Statistical Analyses

Tacrolimus intrapatient variability was examined in relation to age at the time of transplantation, age at the time of tacrolimus measurement, and duration of post-transplant follow-up. Spline curves were generated from quartiles on the basis of coefficient of variation values to create percentile curves for tacrolimus variability by age at the time of transplant and by post-transplant time. Coefficient of variation was censored at the time of de novo DSA detection to exclude clinician-directed tacrolimus dose adjustments in the treatment of rejection. For those with graft loss, coefficient of variation was censored at the time of biopsy-proven rejection, de novo DSA detection, or graft loss if the biopsy did not demonstrate rejection. Multivariable Cox regression models were performed to assess the association of tacrolimus variability with C1q-binding de novo DSA formation and secondary graft outcomes. Tacrolimus intrapatient variability was included in the Cox regression models as a continuous variable, a categorical variable (high versus low), and quartiles determined by data from the study population. High tacrolimus intrapatient variability was defined as a coefficient of variation >30%, which correlated with cutoffs used in adult studies and corresponded to our population median of 30% (12,26). Various cutoffs for intrapatient variability were used in the analyses, and intrapatient variability and age at measurement of tacrolimus level were included as time-varying variables given the potential for effect modification. Multivariable Cox regression models were used to adjust for potential confounders. Observations that occurred in the first 10 months post-transplant were excluded from analysis as intrapatient variability was found to be highly irregular in the initial 10 months post-transplant in the study population. Tacrolimus intrapatient variability after 10 months post-transplant was examined within the outcome cohort in relation to de novo DSA formation using the Mann–Whitney U test. A P value of 0.05 was reported as statistically significant. Analyses were performed using R and GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

Results

Tacrolimus Intrapatient Variability Patterns in Pediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients

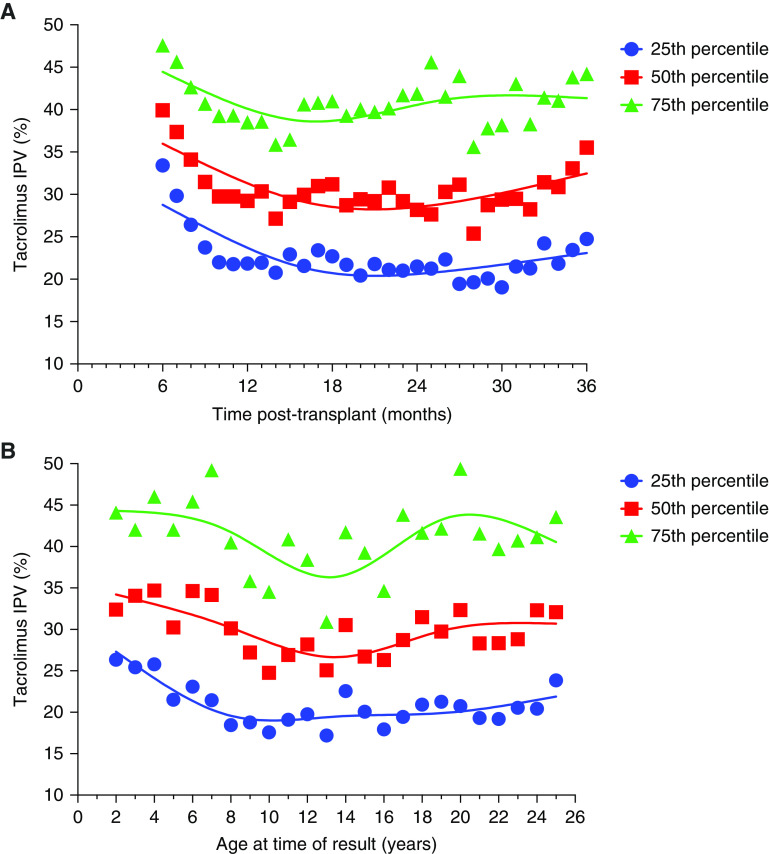

Of the 455 patients who underwent kidney-only transplantation at our center, 426 met the inclusion criteria to determine trends in tacrolimus intrapatient variability. A total of 31,125 tacrolimus levels (median, 64 levels per patient; interquartile range [IQR], 33–96) were analyzed. Median follow-up time was 36 months (IQR, 15–73), mean age at transplant was 11±6 years, and 221 (52%) were boys. Percentile curves for tacrolimus intrapatient variability were generated, plotting the mean coefficient of variation by time post-transplant (Figure 1A). The mean coefficient of variation stabilized at 10 months post-transplant, and after that, the median of the mean coefficient of variation for this population was 30% (IQR, 21%–41%). The median coefficient of variation varied with age. Figure 1B shows that intrapatient variability was greater and that the median value was higher in the youngest patients for all percentiles. Additional trend graphs are presented in Supplemental Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trends in tacrolimus intrapatient variability in the study population. Percentile curves for tacrolimus intrapatient variability (IPV) for the entire cohort (n=426) were generated using spline curves to depict (A) tacrolimus IPV over time post-transplant and (B) tacrolimus IPV by age at the time of tacrolimus result.

Characteristics of the Outcome Cohort

A total of 220 patients met criteria for investigating outcomes. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 14,954 tacrolimus trough levels were analyzed. The median number of tacrolimus trough levels per patient was 59 (IQR, 38–87). The median tacrolimus trough level during the entire post-transplant course was 8.0 ng/ml (IQR, 7.0–9.1), and after 10 months post-transplant, the median was 5.8 ng/ml (IQR, 4.4–7.5). Median follow-up time was 44 months (IQR, 26–66). Fifty-one patients formed C1q-binding de novo DSAs, of which 20 were detected within the first 10 months post-transplant. Fourteen patients lost their graft due to immunologic causes (n=13) or cancer chemotherapy nephrotoxicity (n=1). Patient characteristics stratified by de novo DSA status are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the outcome cohort

| Characteristic | n=220 |

|---|---|

| Recipient age, yr | 13 (5–16) |

| Recipient sex | |

| Boys | 117 (53) |

| Living donor kidney transplantation | 54 (25) |

| HLA match | |

| 0–1 | 120 (55) |

| 2–4 | 97 (44) |

| 5–6 | 3 (1) |

| Peak PRA, % | |

| <10 | 121 (55) |

| 10–49 | 65 (30) |

| 50–100 | 34 (15) |

| Follow-up time, mo | 44 (26–66) |

| No. of tacrolimus trough levels per patient | 59 (38–87) |

| Median tacrolimus trough level,a ng/ml | 5.8 (4.4–7.5) |

| Median tacrolimus IPV,a % | 31 (22–42) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and as number (percentage) for categorical variables. Peak PRA indicates historic peak PRA. PRA, panel reactive antibody; No., number; IPV, intrapatient variability.

Tacrolimus levels before 10 months post-transplant were excluded from these analyses.

Table 2.

Comparison of nondonor-specific antibody formers with those who formed C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibodies in the outcome cohort (n=220)

| Characteristic | No C1q-Binding De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody Formation, n=169 | C1q-Binding De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody Formation, n=51 |

|---|---|---|

| Age at time of transplant, yr | 12 (5–16) | 14 (3–16) |

| Boys, n (%) | 87 (51) | 30 (59) |

| Living donor kidney transplant, n (%) | 42 (25) | 12 (24) |

| HLA match | 1 (1–3) | 1 (0–3) |

| Peak PRA, % | 4 (0–27) | 23 (0–50) |

| Follow-up time, mo | 46 (25–68) | 44 (28–72) |

| Graft loss, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 13 (26) |

| Median no. of tacrolimus trough levels per patient | 68 (47–94) | 36 (24–54) |

| Median tacrolimus trough level, ng/ml | 5.6 (4.4–7.2) | 6.3 (4.6–8.4) |

| Median tacrolimus IPV,a % | 28 (20–38) | 38 (28–48) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and as number (percentage) for categorical variables. Peak PRA indicates historic peak PRA. PRA, panel reactive antibody; no., number; IPV, intrapatient variability.

Tacrolimus levels before 10 months post-transplant were excluded from these analyses.

Tacrolimus Intrapatient Variability and Graft Outcomes

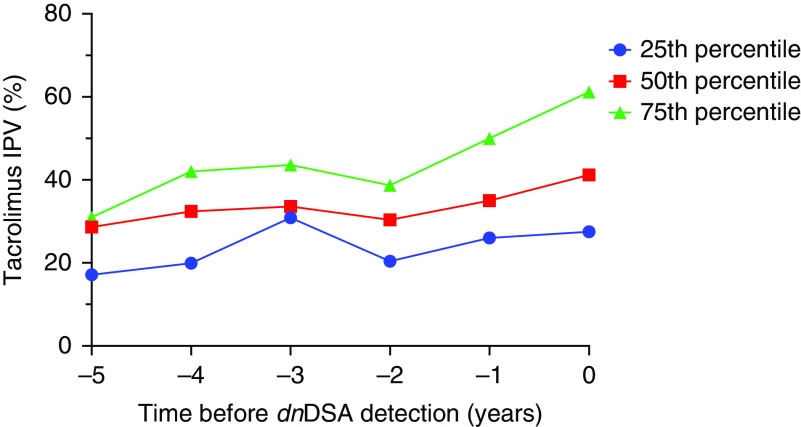

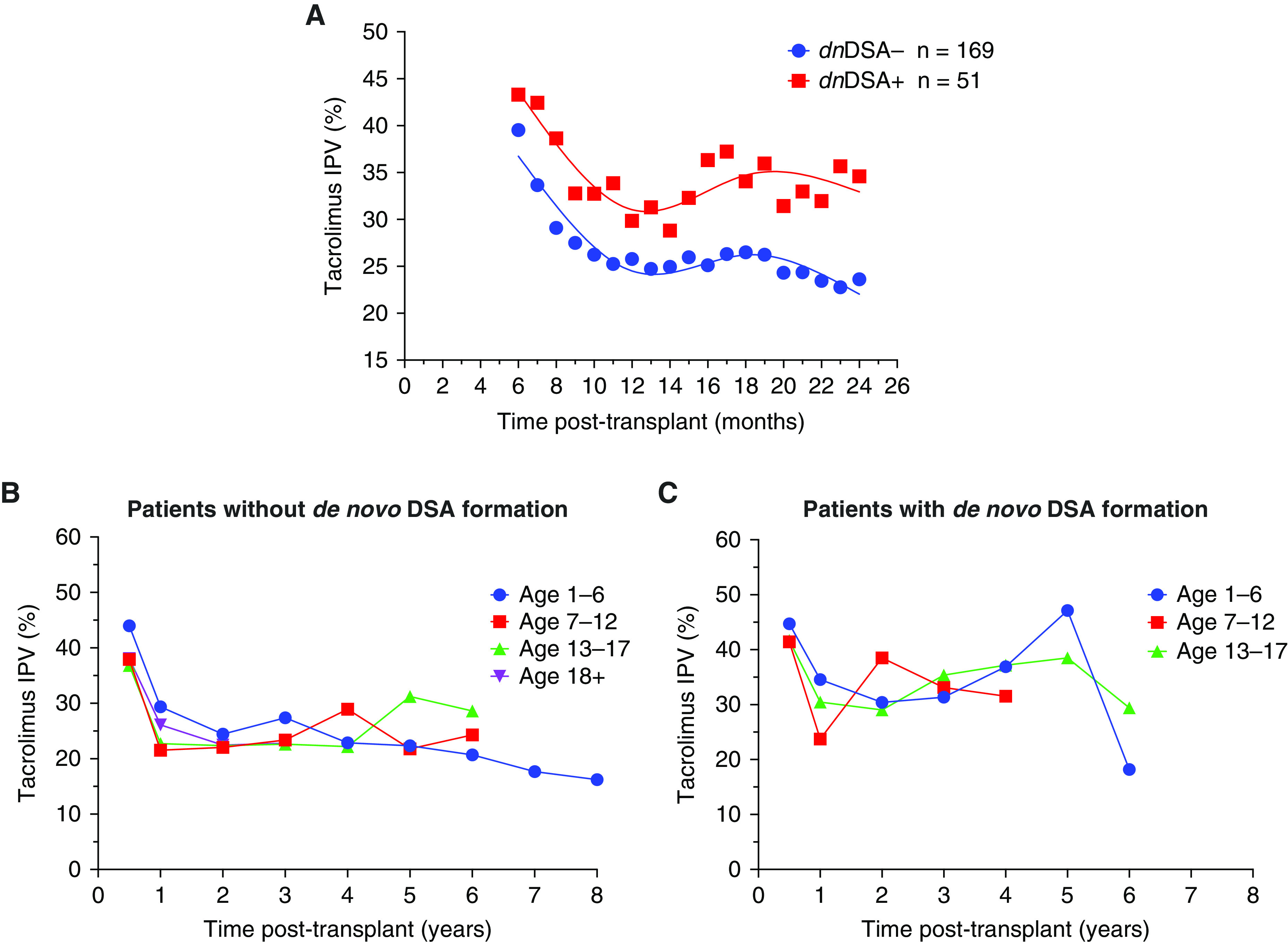

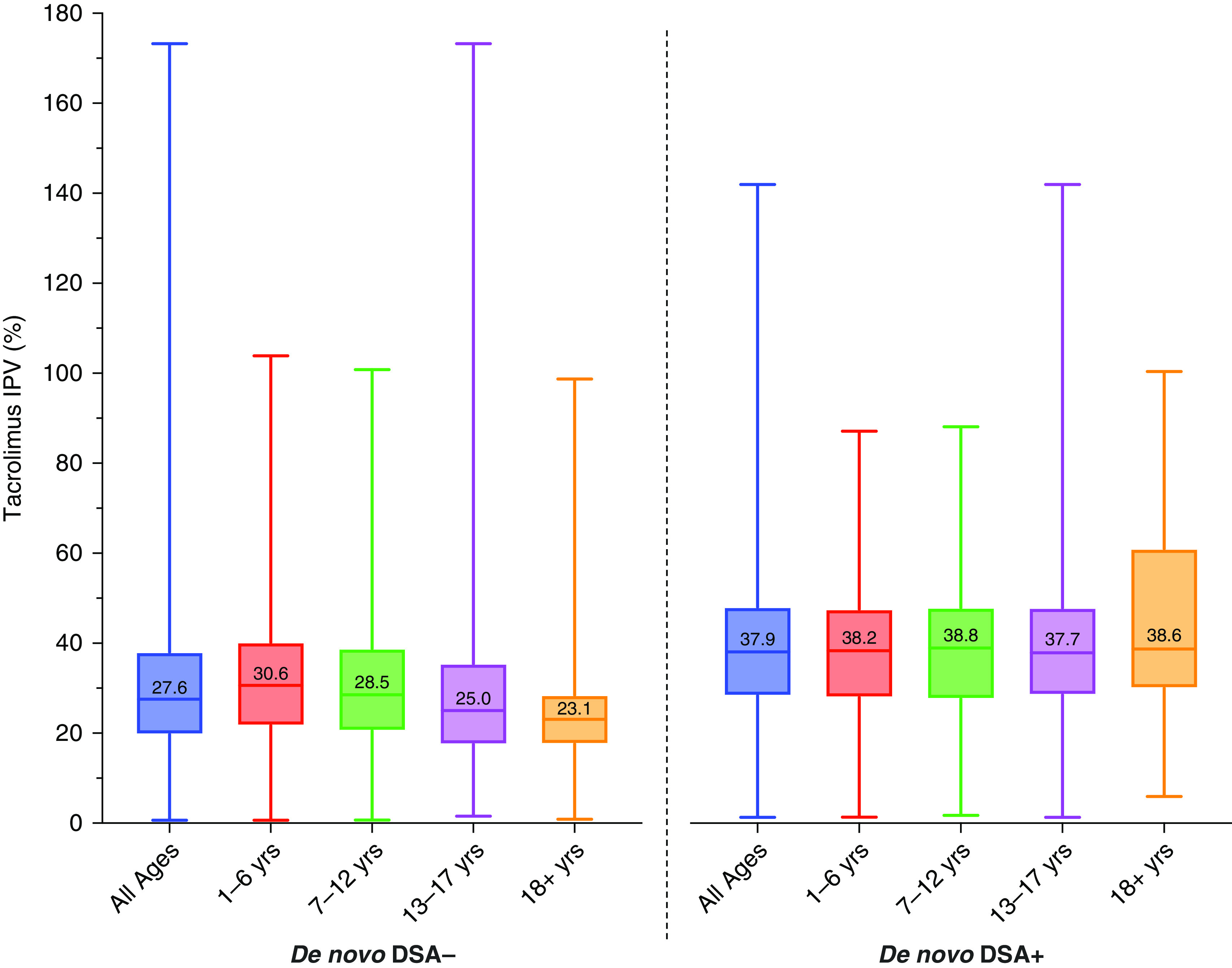

Patients who formed C1q-binding de novo DSAs had a higher median coefficient of variation in the initial 2 years post-transplant compared with those who did not form de novo DSAs (Figure 2A); this pattern persisted for several years post-transplant when patients were stratified by de novo DSA status and age (Figure 2, B and C). Data were excluded from Figure 2, B and C if there were fewer than three participants per time point after transplantation. Additionally, those who formed C1q-binding de novo DSAs had an upward trend in tacrolimus intrapatient variability during the time leading up to DSA detection (Figure 3). Because tacrolimus intrapatient variability in the entire cohort was high during the first 10 months post-transplant, patients who formed de novo DSAs before 10 months post-transplant (n=20) were excluded from the analysis. Patients who formed de novo DSAs after 10 months post-transplant had significantly higher tacrolimus intrapatient variability, with median coefficient of variation of 38% (IQR, 28%–48%) compared with median coefficient of variation of 28% (IQR, 20%–38%) for non-DSA formers; this pattern persisted for all age groups (P<0.001) (Figure 4, Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Tacrolimus intrapatient variability trends over time in de novo DSA formers compared with nonformers. Tacrolimus IPV trends in the outcome cohort (n=220) were compared by (A) C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibody (DSA) status, and stratified by age groups for (B) patients without de novo DSA formation and (C) patients with de novo DSA formation. Data were excluded from (B) and (C) if there were fewer than three participants per time point after transplantation.

Figure 3.

Tacrolimus IPV trended upward in the time leading up to de novo DSA detection. Percentile curves for tacrolimus IPV over time before C1q-binding de novo DSA detection (n=51) in the outcome cohort (time of de novo DSA detection =0 years). dnDSA, de novo DSA.

Figure 4.

Box plots depicting distribution of tacrolimus IPV by de novo DSA status and stratified by age group. Tacrolimus IPV for non-DSA formers (de novo DSA−) is compared with tacrolimus IPV for patients who formed C1q-binding de novo DSAs (de novo DSA+) and is stratified by age groups of 1–6, 7–12, 13–17, and 18+ years (n=200), with median tacrolimus IPV values displayed. Only patients who formed de novo DSA+ at least 10 months post-transplant were included in the de novo DSA group. Tacrolimus IPV was calculated starting from 10 months post-transplantation. The P value was <0.001 for comparisons between de novo DSA− and de novo DSA+ groups for all ages and for each set of age groups by the Mann–Whitney U test.

In the bivariate analyses (Table 3), the risk of de novo DSA formation was found to be significantly higher in patients with high tacrolimus intrapatient variability defined as >30%. This was found to be significant for de novo DSA formation by both C1q (HR, 5.03; 95% CI, 2.33 to 10.84) and by anti-HLA class 2 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.86 to 4.96). Tacrolimus intrapatient variability in the top quartile (defined as tacrolimus intrapatient variability >41%) had the strongest association with de novo DSA formation by both C1q (HR, 11.51; 95% CI, 4.58 to 28.91) and anti-HLA class 2 (HR, 4.16; 95% CI, 2.14 to 8.09). No association was observed between age at tacrolimus measurement, sex, donor source, HLA match, or tacrolimus level and de novo DSA formation by C1q or class 2 IgG. Results from the bivariate analyses determined the variables used in the multivariable regression analyses (Table 4). These adjusted models show that tacrolimus intrapatient variability was strongly associated with C1q-binding de novo DSA formation regardless of whether intrapatient variability was incorporated as a continuous variable (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.05) or a categorical variable with high intrapatient variability defined as >30% (HR, 5.35; 95% CI, 2.45 to 11.68) or when stratified by quartiles determined by baseline data, with the top quartile having the strongest association (HR, 11.81; 95% CI, 4.76 to 29.27). Tacrolimus intrapatient variability >30% and the top quartile were also found to be significantly associated with graft loss in an unadjusted model (Supplemental Table 4), but after adjusting for the presence of C1q-binding de novo DSA, the association was no longer significant.

Table 3.

Association between de novo donor-specific antibody formation by C1q, de novo anti-HLA class 2 donor-specific antibody formation, development of proteinuria, and eGFR decline to <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with other variables in the outcome cohort

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1q-Binding De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody | Anti-HLA Class 2 De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody | Proteinuria: Urine Protein-Creatinine Ratio ≥0.5 mg/mg for ≥3 mo | eGFR Decline to <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for ≥3 mo | |

| Age at transplant, yr | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.14)a | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.17)a | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.12) |

| Age at tacrolimus measurement, yr | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.13) | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.07) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16)a | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) |

| Boys | 0.97 (0.47 to 1.99) | 0.99 (0.61 to 0.62) | 0.92 (0.45 to 1.97) | 0.51 (0.23 to 1.14) |

| Living donor | 1.35 (0.58 to 3.11) | 1.63 (0.92 to 2.89) | 1.67 (0.69 to 4.04) | 1.05 (0.45 to 2.36) |

| HLA match | 0.91 (0.65 to 1.28) | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.11) | 0.75 (0.36 to 1.00)a | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.05) |

| Peak PRA | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Tacrolimus level | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16) | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.11) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.16)a |

| Tacrolimus IPV (continuous variable) | 1.04 (1.03 to 1.05)a | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Tacrolimus IPV >30% (high versus low) | 5.03 (2.33 to 10.84)a | 3.04 (1.86 to 4.96)a | 1.92 (0.87 to 4.23) | 2.19 (1.02 to 4.69)a |

| Tacrolimus IPV by quartiles b | ||||

| First quartile | — | — | — | — |

| Second quartile | 3.19 (1.20 to 8.48)a | 1.54 (0.80 to 2.95) | 2.76 (1.06 to 7.17)a | 1.00 (0.31 to 3.21) |

| Third quartile | 3.15 (0.85 to 11.62) | 3.99 (1.99 to 7.71)a | 2.30 (0.61 to 8.70) | 4.29 (1.80 to 10.20)a |

| Fourth quartile | 11.51 (4.58 to 28.91)a | 4.16 (2.14 to 8.09)a | 2.94 (0.86 to 10.02) | 1.45 (0.41 to 5.17) |

Tacrolimus IPV was used as a time-dependent variable. Urine protein-creatinine ratio is in milligrams per milligram. Peak PRA indicates historic peak PRA. PRA, panel reactive antibody; IPV, intrapatient variability; —, not analyzed.

P<0.05.

Tacrolimus IPV cutoffs by quartiles calculated from the entire cohort: first quartile (25th percentile): 21%; second quartile (50th percentile): 30%; third quartile (75th percentile): 41%; and fourth quartile (100th percentile): 173%.

Table 4.

Adjusted association between tacrolimus intrapatient variability and C1q-binding de novo donor-specific antibody formation in the outcome cohort

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

| Tacrolimus IPV (continuous variable) | 1.04 (1.03 to 1.05) | ||

| Tacrolimus IPV >30% | 5.35 (2.45 to 11.68) | ||

| Tacrolimus IPV, quartiles d | |||

| First | — | ||

| Second | 3.35 (1.27 to 8.88) | ||

| Third | 3.54 (0.93 to 13.39) | ||

| Fourth | 11.81 (4.76 to 29.27) | ||

Tacrolimus IPV was used as a time-dependent variable. IPV, intrapatient variability; —, not analyzed.

Tacrolimus IPV as a continuous variable adjusted for age at transplantation and peak panel reactive antibody.

Tacrolimus IPV categorized as under or over 30% adjusted for age at transplantation and peak panel reactive antibody.

Tacrolimus IPV categorized by quartiles adjusted for age at transplantation and peak panel reactive antibody.

Tacrolimus IPV cutoffs by quartiles calculated from entire cohort: first quartile (25th percentile): 21%; second quartile (50th percentile): 30%; third quartile (75th percentile): 41%; fourth quartile (100th percentile): 173%.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we determined the baseline tacrolimus intrapatient variability patterns in a large cohort of participants who underwent kidney transplantation at a single pediatric center. We noted that tacrolimus intrapatient variability was initially high for all ages and stabilized at approximately 10 months post-transplant. Similar to previous studies, high tacrolimus intrapatient variability was associated with de novo DSA formation in our cohort (20,27,28). We observed that patients who formed de novo DSAs had patterns of higher intrapatient variability in the first 2 years after transplantation and rising tacrolimus variability even in the years prior to DSA detection compared with nonformers.

Although baseline trends of tacrolimus variability have been assessed in adult transplant populations (29), patterns of tacrolimus variability have not been well defined in pediatric patients with kidney transplants. Tacrolimus intrapatient variability was high during the immediate post-transplant period for all ages, likely due to frequent changes in tacrolimus dosing and target levels, medication interactions, and feeding intolerance or gastrointestinal losses. We suggest that for evaluation of tacrolimus variability in pediatric kidney transplant recipients, the early post-transplant period should be defined as the first 10 months and that future studies assessing outcomes should, therefore, focus on the period beyond 10 months. Median tacrolimus intrapatient variability after 10 months post-transplant was 30%, consistent with large adult population data that demonstrated median tacrolimus variability of 31% (13). Other studies in adults found variability ranging from 15% to 30% (29–32). A recent pediatric study of 48 patients used a cutoff of 25% for high variability as determined by their population median (20).

In a recent prospective, randomized controlled trial in adults that included both patients with kidney transplants and patients with liver transplants, low tacrolimus intrapatient variability correlated with high medication adherence (29). The median coefficient of variation in patients with kidney transplants was 17%, which is significantly lower than in our study. Medication nonadherence is considered the strongest contributor to high tacrolimus intrapatient variability (29,33). Recent studies have reported medication nonadherence in approximately 30% of pediatric patients with kidney transplants and rates of approximately 40% in the adolescent kidney transplant population (34,35). Higher incidence of graft loss during late adolescence and early adulthood is thought to be due to greater rates of medication nonadherence related to their development and growing independence (1,10,36,37), which is likely a major determinant of the high tacrolimus intrapatient variability in this age group. Nonetheless, this is an unlikely explanation of the higher variability trends in the youngest children who rely exclusively on their caregivers to administer their medications. Higher tacrolimus intrapatient variability in young children could be due to tube feeding affecting medication absorption, feeding intolerance, and more frequent childhood illness, including diarrheal illness requiring significant tacrolimus dose reduction (9).

We found that tacrolimus intrapatient variability >30% was highly associated with de novo DSA formation by both C1q and IgG class 2 anti-HLA. These findings are consistent with several studies that have linked high tacrolimus intrapatient variability in patients with kidney transplants to de novo DSA formation, rejection, and graft loss (8,14,17,19,26,38). Recent pediatric studies that followed patients past the first post-transplant year demonstrated that tacrolimus intrapatient variability >30% was associated with adverse graft outcomes, with a total number of patients ranging from 38 to 67 (19,27,39). Solomon et al. (19) identified high tacrolimus intrapatient variability as an independent risk factor for de novo DSA formation in pediatric patients with kidney transplants and found that a coefficient of variation ≥30% was associated with a higher incidence of allograft rejection. Similarly, a multicenter study of 6600 adult patients with kidney-only transplants demonstrated that patients with tacrolimus intrapatient variability ≥30% were at a higher risk of graft loss (12). Rodrigo et al. (26) reported that high variability, with a coefficient of variation >30%, promoted de novo DSA development, supporting the tacrolimus intrapatient variability risk threshold established in our study. Furthermore, in our study, the top quartile of tacrolimus intrapatient variability had the strongest association with de novo DSA formation. This suggests a dose-response relationship between tacrolimus intrapatient variability and de novo DSA formation, with increasing values of tacrolimus intrapatient variability above the threshold of 30% corresponding to higher risk of de novo DSA formation.

Limitations of this study include those inherent to its retrospective study design. Although this could be considered a large pediatric study, the sample size is relatively small compared with existing adult studies. Additionally, as this was a single-center study, the results may not be broadly applicable. Low mycophenolic acid exposure has been associated with the development of de novo DSA (40). Because mycophenolic acid levels are not closely followed at our center, we were unable to include that variable. An additional limitation of the study was not incorporating dose-normalized tacrolimus levels. A retrospective chart review did not allow that as doses are changed by phone frequently by our transplant team and not consistently updated in a patient’s medication list. We were also unable to correct for possible minor local variations in tacrolimus detection methods in the variability calculations or exclude patients in whom the target tacrolimus level was altered in the setting of an illness. Finally, the effect of confounding factors, such as the frequency and setting of blood sample collection, incorrect timing of trough levels, or patients missing blood draws due to nonadherence, could not be assessed as these observations go beyond the scope of this study. The retrospective design did not allow for assessment of the cause of fluctuations in tacrolimus concentration.

One notable strength of this study is that all available tacrolimus trough levels were included in the analyses. This approach resulted in the inclusion of over tens of thousands of tacrolimus levels for analysis and thus, a large number of trough levels per patient. A criticism of many other studies is that patients may only have had a few tacrolimus levels available. Many reports have included a median number of measured levels ranging from three to 15 (9,20). Our baseline pattern data were generated using a median of 64 levels, which markedly improves the accuracy of our results. Our large referral center follows patients whose blood is analyzed in a variety of laboratories; these include national and local commercial laboratories as well as hospital-based laboratories using different analytical techniques. Many patients get blood drawn from more than one laboratory due to convenience or insurance coverage demands. Our patients received tacrolimus both in the immediate- and extended-release forms, with generic and originator formulations. All of these are potential confounders that would be expected to conspire to result in higher tacrolimus variability and reduce the likelihood of identifying a difference between patients at risk for poor graft outcomes or not. The strength of the correlation we have identified despite the potential shortcomings of clinical practice data speaks to the relevance of this association.

The results of this study establish baseline patterns of tacrolimus intrapatient variability in pediatric patients at various times after kidney transplantation. This large pediatric cohort study of baseline patterns may be useful in the design of prospective pediatric studies to further investigate the relationship between tacrolimus intrapatient variability and adverse graft outcomes. Our study confirms the findings of prior studies that high tacrolimus intrapatient variability is associated with inferior outcomes in pediatric patients with kidney transplants. By including all available tacrolimus levels when calculating the coefficient of variation, tacrolimus intrapatient variability can be easily incorporated into an institution’s EHR to quickly identify high-risk patients with transplants, allowing for early intervention. Reducing tacrolimus intrapatient variability could be vital for improving long-term graft outcomes. Future larger-scale prospective trials are warranted to investigate the determinants of tacrolimus intrapatient variability and better determine the threshold value of increased immunologic risk.

Disclosures

A. Chaudhuri reports employment with Stanford University. A. Gallo reports employment with Stanford University and ownership interest in Apple, Netflix, Nike, and Square. P.C. Grimm reports employment with Stanford University; consultancy agreements with Eloxx, Horizon, Medscape, and Recordati; research funding from Alexion Pharmaceuticals; honoraria from Eloxx, Horizon, Medscape, and Recordati; and serving as a board member of the Improve Renal Outcomes Collaborative. L. Maestretti reports employment with Stanford Children's Health. M.V. Patton's spouse is employed by Eclipse Ventures and is an investor in BrightInsight, Cellares, Forsight Robotics, Lucira, and Rune Labs. V.K. Sigurjonsdottir reports research funding from a Landspitali–The National University Hospital of Iceland Young Scientist Award. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The project described in this manuscript was supported by the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. K.H.P. was a Marion and Jack Euphrat Pediatric Translational Medicine Endowed Postdoctoral Fellow of the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute (PTA no. 1105286-108-KHABU). K.H.P. was also funded by the Stanford University Transplant and Tissue Engineering Center of Excellence (PTA no. 1244315-100-JHAJR). V.K.S. was a Tashia and John Morgridge Endowed Postdoctoral Fellow of the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute (PTA no. 1220322‐100‐JCHAA). V.K.S. also received a Young Scientist Award at Landspitali–The National University Hospital of Iceland.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our clinical analyst Rajesh Shetty for his valued assistance.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Pathophysiological Implications of Variability in Blood Tacrolimus Levels in Pediatric and Adolescent Kidney Transplant Recipients,” on pages 1105–1106.

Author Contributions

A. Chaudhuri, P.C. Grimm, L. Maestrett, A. McGrath, M.V. Patton, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir conceptualized the study; L. Maestrett, A. McGrath, M.V. Patton, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for data curation; L. Maestrett, A. McGrath, M.V. Patton, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for investigation; O.S. Indridason, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for formal analysis; A. Chaudhuri, P.C. Grimm, O.S. Indridason, L. Maestrett, A. McGrath, M.V. Patton, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for methodology; P.C. Grimm, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for project administration; A. Chaudhuri, A. Gallo, P.C. Grimm, O.S. Indridason, L. Maestrett, A. McGrath, and M.V. Patton were responsible for validation; P.C. Grimm, O.S. Indridason, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for visualization; A. Chaudhuri, P.C. Grimm, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir were responsible for funding acquisition; A. Chaudhuri, P.C. Grimm, O.S. Indridason, R. Palsson, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir provided supervision; K.H. Piburn and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir wrote the original draft; and A. Chaudhuri, A. Gallo, P.C. Grimm, O.S. Indridason, L. Maestrett, A. McGrath, R. Palsson, M.V. Patton, K.H. Piburn, and V.K. Sigurjonsdottir reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at https://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.16421221/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Target tacrolimus trough levels on the basis of time post-transplant.

Supplemental Table 2. Routine post-transplant surveillance as per Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford’s kidney transplant protocol.

Supplemental Table 3. Results of the Mann–Whitney U test comparing tacrolimus intrapatient variability in patients who formed C1q-binding de novo DSAs with non-DSA formers for all ages and for each age group.

Supplemental Table 4. Association between graft loss and other variables in the outcome cohort (n=220).

Supplemental Figure 1. Percentile curves for tacrolimus CV by time post-transplant stratified by age at the time of transplant.

References

- 1.Dharnidharka VR, Fiorina P, Harmon WE: Kidney transplantation in children. N Engl J Med 371: 549–558, 2014. 10.1056/NEJMra1314376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreoni KA, Forbes R, Andreoni RM, Phillips G, Stewart H, Ferris M: Age-related kidney transplant outcomes: Health disparities amplified in adolescence. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1524–1532, 2013. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) . OPTN/SRTR 2017 Annual Data Report. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2018. Accessed June 2, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu M, Liu M, Zhang W, Ming Y: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenetics of tacrolimus in kidney transplantation. Curr Drug Metab 19: 513–522, 2018. 10.2174/1389200219666180129151948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staatz CE, Tett SE: Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet 43: 623–653, 2004. 10.2165/00003088-200443100-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barraclough KA, Staatz CE, Johnson DW, Lee KJ, McWhinney BC, Ungerer JP, Hawley CM, Campbell SB, Leary DR, Isbel NM: Kidney transplant outcomes are related to tacrolimus, mycophenolic acid and prednisolone exposure in the first week. Transpl Int 25: 1182–1193, 2012. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larkins N, Matsell DG: Tacrolimus therapeutic drug monitoring and pediatric renal transplant graft outcomes. Pediatr Transplant 18: 803–809, 2014. 10.1111/petr.12369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold A, Tönshoff B, Döhler B, Süsal C: Association of graft survival with tacrolimus exposure and late intra-patient tacrolimus variability in pediatric and young adult renal transplant recipients-an international CTS registry analysis. Transpl Int 33: 1681–1692, 2020. 10.1111/tri.13726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzales HM, McGillicuddy JW, Rohan V, Chandler JL, Nadig SN, Dubay DA, Taber DJ: A comprehensive review of the impact of tacrolimus intrapatient variability on clinical outcomes in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 20: 1969–1983, 2020. 10.1111/ajt.16002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pizzo HP, Ettenger RB, Gjertson DW, Reed EF, Zhang J, Gritsch HA, Tsai EW: Sirolimus and tacrolimus coefficient of variation is associated with rejection, donor-specific antibodies, and nonadherence. Pediatr Nephrol 31: 2345–2352, 2016. 10.1007/s00467-016-3422-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feddersen N, Pape L, Beneke J, Brand K, Prüfe J: Adherence in pediatric renal recipients and its effect on graft outcome, a single-center, retrospective study. Pediatr Transplant 25: e13922, 2021. 10.1111/petr.13922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Süsal C, Döhler B: Late intra-patient tacrolimus trough level variability as a major problem in kidney transplantation: A Collaborative Transplant Study report. Am J Transplant 19: 2805–2813, 2019. 10.1111/ajt.15346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah PB, Ennis JL, Cunningham PN, Josephson MA, McGill RL: The epidemiologic burden of tacrolimus variability among kidney transplant recipients in the United States. Am J Nephrol 50: 370–374, 2019. 10.1159/000503167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whalen HR, Glen JA, Harkins V, Stevens KK, Jardine AG, Geddes CC, Clancy MJ: High intrapatient tacrolimus variability is associated with worse outcomes in renal transplantation using a low-dose tacrolimus immunosuppressive regime. Transplantation 101: 430–436, 2017. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mo H, Kim SY, Min S, Han A, Ahn S, Min SK, Lee H, Ahn C, Kim Y, Ha J: Association of intrapatient variability of tacrolimus concentration with early deterioration of chronic histologic lesions in kidney transplantation. Transplant Direct 5: e455, 2019. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rozen-Zvi B, Schneider S, Lichtenberg S, Green H, Cohen O, Gafter U, Chagnac A, Mor E, Rahamimov R: Association of the combination of time-weighted variability of tacrolimus blood level and exposure to low drug levels with graft survival after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 393–399, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu Bakar K, Mohamad NA, Hodi Z, McCulloch T, Williams A, Christian M, Key T, Kim JJ: Defining a threshold for tacrolimus intra-patient variability associated with late acute cellular rejection in paediatric kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr Nephrol 34: 2557–2562, 2019. 10.1007/s00467-019-04346-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiau M, Fernandez HE, Gjertson D, Ettenger RB, Tsai EW: Monitoring nonadherence and acute rejection with variation in blood immunosuppressant levels in pediatric renal transplantation. Transplantation 92: 918–922, 2011. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822dc34f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon S, Colovai A, Del Rio M, Hayde N: Tacrolimus variability is associated with de novo donor-specific antibody development in pediatric renal transplant recipients. Pediatr Nephrol 35: 261–270, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baghai Arassi M, Gauche L, Schmidt J, Höcker B, Rieger S, Süsal C, Tönshoff B, Fichtner A: Association of intraindividual tacrolimus variability with de novo donor-specific HLA antibody development and allograft rejection in pediatric kidney transplant recipients with low immunological risk [published online ahead of print February 15, 2022]. Pediatr Nephrol 10.1007/s00467-022-05426-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanford Health Care, Stanford Medicine, Stanford Anatomic Pathology & Clinical Laboratories : Tacrolimus (FK506). Available at: https://stanfordlab.com/content/stanfordlab/en/test-details/f/FK506L.html. Accessed March 17, 2022

- 22.Quest Diagnostics : Tacrolimus, Highly Sensitive, LC/MS/MS. Available at: https://testdirectory.questdiagnostics.com/test/test-detail/70007/tacrolimus-highly-sensitive-lcmsms?p=r&q=tacrolimus&cc=MASTER. Accessed March 17, 2022

- 23.LabCorp. : Tacrolimus, Whole Blood. Available at: https://www.labcorp.com/tests/700248/tacrolimus-whole-blood. Accessed March 17, 2022

- 24.Reed EF, Rao P, Zhang Z, Gebel H, Bray RA, Guleria I, Lunz J, Mohanakumar T, Nickerson P, Tambur AR, Zeevi A, Heeger PS, Gjertson D: Comprehensive assessment and standardization of solid phase multiplex-bead arrays for the detection of antibodies to HLA. Am J Transplant 13: 1859–1870, 2013. 10.1111/ajt.12287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigurjonsdottir VK, Purington N, Chaudhuri A, Zhang BM, Fernandez-Vina M, Palsson R, Kambham N, Charu V, Piburn K, Maestretti L, Shah A, Gallo A, Concepcion W, Grimm PC: Complement-binding donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies: Biomarker for immunologic risk stratification in pediatric kidney transplantation recipients [published online ahead of print March 16, 2022]. Transpl Int 35: 11, 2022. 10.3389/ti.2021.10158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrigo E, Segundo DS, Fernández-Fresnedo G, López-Hoyos M, Benito A, Ruiz JC, de Cos MA, Arias M: Within-patient variability in tacrolimus blood levels predicts kidney graft loss and donor-specific antibody development. Transplantation 100: 2479–2485, 2016. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaya Aksoy G, Comak E, Koyun M, Akbaş H, Akkaya B, Aydınlı B, Uçar F, Akman S: Tacrolimus variability: A cause of donor-specific anti-HLA antibody formation in children. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 44: 539–548, 2019. 10.1007/s13318-019-00544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis S, Gralla J, Klem P, Stites E, Wiseman A, Cooper JE: Tacrolimus intrapatient variability, time in therapeutic range, and risk of de novo donor-specific antibodies. Transplantation 104: 881–887, 2020. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leino AD, King EC, Jiang W, Vinks AA, Klawitter J, Christians U, Woodle ES, Alloway RR, Rohan JM: Assessment of tacrolimus intrapatient variability in stable adherent transplant recipients: Establishing baseline values. Am J Transplant 19: 1410–1420, 2019. 10.1111/ajt.15199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahamimov R, Tifti-Orbach H, Zingerman B, Green H, Schneider S, Chagnac A, Mor E, Fox BD, Rozen-Zvi B: Reduction of exposure to tacrolimus trough level variability is associated with better graft survival after kidney transplantation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75: 951–958, 2019. 10.1007/s00228-019-02643-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko H, Kim HK, Chung C, Han A, Min SK, Ha J, Min S: Association between medication adherence and intrapatient variability in tacrolimus concentration among stable kidney transplant recipients. Sci Rep 11: 5397, 2021. 10.1038/s41598-021-84868-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herblum J, Dacouris N, Huang M, Zaltzman J, Prasad GVR, Nash M, Chen L: Retrospective analysis of tacrolimus intrapatient variability as a measure of medication adherence. Can J Kidney Health Dis 8: 20543581211021742, 2021. 10.1177/20543581211021742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGillicuddy JW, Chandler JL, Sox LR, Taber DJ: Exploratory analysis of the impact of an mhealth medication adherence intervention on tacrolimus trough concentration variability: Post hoc results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Pharmacother 54: 1185–1193, 2020. 10.1177/1060028020931806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmberg C: Nonadherence after pediatric renal transplantation: Detection and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr 31: 219–225, 2019. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobbels F, Ruppar T, De Geest S, Decorte A, Van Damme-Lombaerts R, Fine RN: Adherence to the immunosuppressive regimen in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. Pediatr Transplant 14: 603–613, 2010. 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Arendonk KJ, James NT, Boyarsky BJ, Garonzik-Wang JM, Orandi BJ, Magee JC, Smith JM, Colombani PM, Segev DL: Age at graft loss after pediatric kidney transplantation: Exploring the high-risk age window. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1019–1026, 2013. 10.2215/CJN.10311012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zelikovsky N, Schast AP, Palmer J, Meyers KEC: Perceived barriers to adherence among adolescent renal transplant candidates. Pediatr Transplant 12: 300–308, 2008. 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Regan JA, Canney M, Connaughton DM, O’Kelly P, Williams Y, Collier G, deFreitas DG, O’Seaghdha CM, Conlon PJ: Tacrolimus trough-level variability predicts long-term allograft survival following kidney transplantation. J Nephrol 29: 269–276, 2016. 10.1007/s40620-015-0230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charnaya O, Tuchman S, Moudgil A: Results of early treatment for de novo donor-specific antibodies in pediatric kidney transplant recipients in a cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort. Pediatr Transplant 22: e13108, 2018. 10.1111/petr.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Filler G, Todorova EK, Bax K, Alvarez-Elías AC, Huang SHS, Kobrzynski MC: Minimum mycophenolic acid levels are associated with donor-specific antibody formation. Pediatr Transplant 20: 34–38, 2016. 10.1111/petr.12637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.