Abstract

Objectives:

Summarize existing literature on cognitive outcomes of MBSR and MBCT for individuals with depression.

Methods:

Following PRISMA (2021) guidance, we conducted a systematic review. We searched databases for studies published from 2000 to 2020 which examined cognitive outcomes of MBSR and MBCT in individuals with at least mild depressive symptoms. The search result in 10 studies (11 articles) meeting inclusion criteria.

Results:

We identified five single armed trials and five randomized controlled trials. Results indicated that three studies did not show any improvements on cognitive outcomes, and seven studies showed at least one improvement in cognitive outcomes.

Conclusions:

Overall, the review highlighted several inconsistencies in the literature including inconsistent use of terminology, disparate samples, and inconsistent use of methodology. These inconsistencies may help to explain the mixed results of MBSR and MBCT on cognitive outcomes. Recommendations include a more streamlined approach to studying cognitive outcomes in depressed individuals in the context of MBSR and MBCT.

Keywords: Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, cognition, depression

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a prevalent and debilitating disorder, with more than 16% of adults in the United States experiencing MDD at some point in their lives (Kessler et al., 2005). Recent estimates suggest that the United States spends more than $210 billion on depression annually (Greenberg et al., 2015). Given the prevalence and impairment associated with MDD, identifying factors which contribute to the onset, maintenance, and recurrence of MDD is of utmost importance. This allows for development and testing of interventions targeted toward modification of the relevant factors.

Cognitive processes serve as one such relevant factor. Miyake et al. (2000) describe a model of executive functioning, comprised of three related, but distinct, components including updating, shifting, and inhibition. Research has shown that depressed and dysphoric individuals show broad cognitive deficits (Austin et al., 2001). A meta-analysis found moderate cognitive deficits in attention, memory, and executive functioning of individuals with MDD (Rock et al., 2014), and another meta-analysis found deficits in executive functions including, and working memory in depressed individuals (Snyder, 2013). Other empirical evidence has shown that depressed individuals display deficits in specific aspects of executive functioning (De Lissnyder et al., 2010; Harvey et al., 2004; Joormann & Gotlib, 2008; Joorman et al., 2007; Levens & Gotlib, 2010; Rogers et al., 2004; Whitmer & Banich, 2007). Furthermore, in depressed individuals, there is documented dysfunction in several regions of the prefrontal cortex associated with executive functioning, including the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), ventrolateral PFC (VLPFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Fitzgerald et al., 2008).

Research examining whether changes in executive functioning accounts for changes in depression symptoms remains relatively mixed, with a meta-analysis suggesting that the impact of cognitive training on depression symptoms is small to moderate (Motter et al., 2016). However, in a review of the impact of executive functioning training on depressive symptoms, researchers found that in many studies which used neutral stimuli to assess executive functioning, improvements in executive functioning were not associated with improvements in depression symptoms (Koster et al., 2017). Of note, the authors indicated that, given the nature of depression and related deficits in executive functioning, effects of executive functioning training on depressive symptoms may be enhanced by specifically targeting and measuring the processing of emotional, rather than neutral, information (Koster et al., 2017). One potential reason why depressed individuals show broad and specific deficits in cognitive processes such as executive functioning may be because depression is associated with information processing biases favoring negative information. Specifically, depressed individuals show sustained attentional biases toward negative information, trouble disengaging from negative information (Armstrong & Olatunji, 2012; Peckham et al., 2010) and a tendency to remember and interpret ambiguous information in a negatively biased manner (Mathews & MacLeod, 2005; Wisco, 2009).

Given the cognitive deficits present in MDD, interventions have been developed to target aspects of these cognitive processes. Mindfulness-based treatments for MDD, and specifically, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), are efficacious treatments for both remitted and current depression (Segal et al., 2002; Strauss, et al., 2014). These 8-week standardized group treatments utilize meditation techniques, psychoeducation, breathing exercises and movement to help individuals to increase present moment awareness in a non-judgmental manner (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Whereas MBSR incorporates the mindfulness skills and movement listed above, MBCT also includes cognitive therapy strategies to help individuals increase meta-awareness and decrease depressogenic cognitions. For example, MBCT helps individuals start to identify negative automatic thoughts that arise throughout one’s day, and helps individuals to notice these thoughts and develop nonjudgmental attitudes towards them (Segal et al., 2002). While MBSR does not specifically address automatic negative thoughts, research has suggested that MBSR also improves existing anxiety and depression symptoms (Fjorback et al., 2011). MBCT has strong evidence in reducing the relapse of MDD for individuals with recurrent depression (Ma & Teasdale, 2004; Teasdale, et al., 2000).

Because mindfulness-based treatments are intended to specifically target cognitive processes associated with MDD, it is important to examine whether these interventions do, in fact, have an impact on such cognitive functions. Furthermore, because MBCT is more specifically designed and targeted to address depressogenic cognitions, it is likely that the effects on cognitive outcomes would be more robust in MBCT compared to MBSR treatment. However, evidence suggests that MBSR does target cognition, showing specific improvement across attentional measures and processing speed (Chiesa et al., 2011). Previous studies and reviews of healthy individuals have found mixed results in terms of the effects of mindfulness-based treatments on cognitive functioning, with some studies finding that these interventions positively affect cognitive functions (Chiesa et al., 2011) and some showing no effect on cognitive functions (Lau et al., 2016). Given that depressed individuals have negative information processing biases and therefore attend to and have trouble disengaging from negative content, MBSR and MBCT may help individuals to disengage and observe, rather than get caught up in these negative thinking styles. To our knowledge, no reviews have characterized the effect of structured mindfulness-based treatments on cognitive functioning in depressed or dysphoric individuals.

The aim of the current systematic review is to describe the literature on the cognitive effects of MBSR and MBCT specifically in depressed individuals. We focused our review on studies that used objective assessments of cognitive deficits (rather than self-report measures). We conducted a systematic review rather than a meta-analysis because we anticipated that articles would present data from a variety of cognitive measures, and that combining the results could obscure important differences between types of cognitive deficits. Furthermore, participants across the studies had different cognitive and neurological disorders; this also precluded combining studies into a single meta-analysis.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included in the systematic review if they focused on adult populations (18 years or older) with at least mild depression symptoms, delivered standardized MBSR or MBCT, and utilized at least one objective, behavioral neuropsychological or neurocognitive outcome measure. Mild depression was determined via set cutoff scores for each depression measure used, and the average score had to be greater than the cutoff for inclusion (See Table 1 for measures and cutoff scores). Because mindfulness research began to expand in the early 2000’s, the search was limited to articles from January 2000 through March 2020, thus capturing 20 years of mindfulness research. Included articles were written in English and published in peer reviewed journals.

Table 1.

Cutoff depression scores used for inclusion.

| Depression Measure Name | Cutoff scores used for inclusion |

|---|---|

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | ≥ 11 |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | ≥ 14 |

| Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21), depression subscale | ≥ 10 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9) | ≥ 5 |

| 18-Item Taiwan Depression Scale (TDS) | ≥ 19 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | ≥ 15 |

| Patient Reported Outcome Measures Information System - Depression (PROMIS-D) | ≥ 16 |

| Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) | ≥ 12 |

Information Source

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., 2021) guidelines. Electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO) were searched to locate studies meeting the above eligibility criteria. Search terms used were: [mindfulness OR meditate* OR MBCT OR MBSR AND attention OR memory OR cogniti* OR executive AND depress* or dysphor*].

Study selection and data extraction

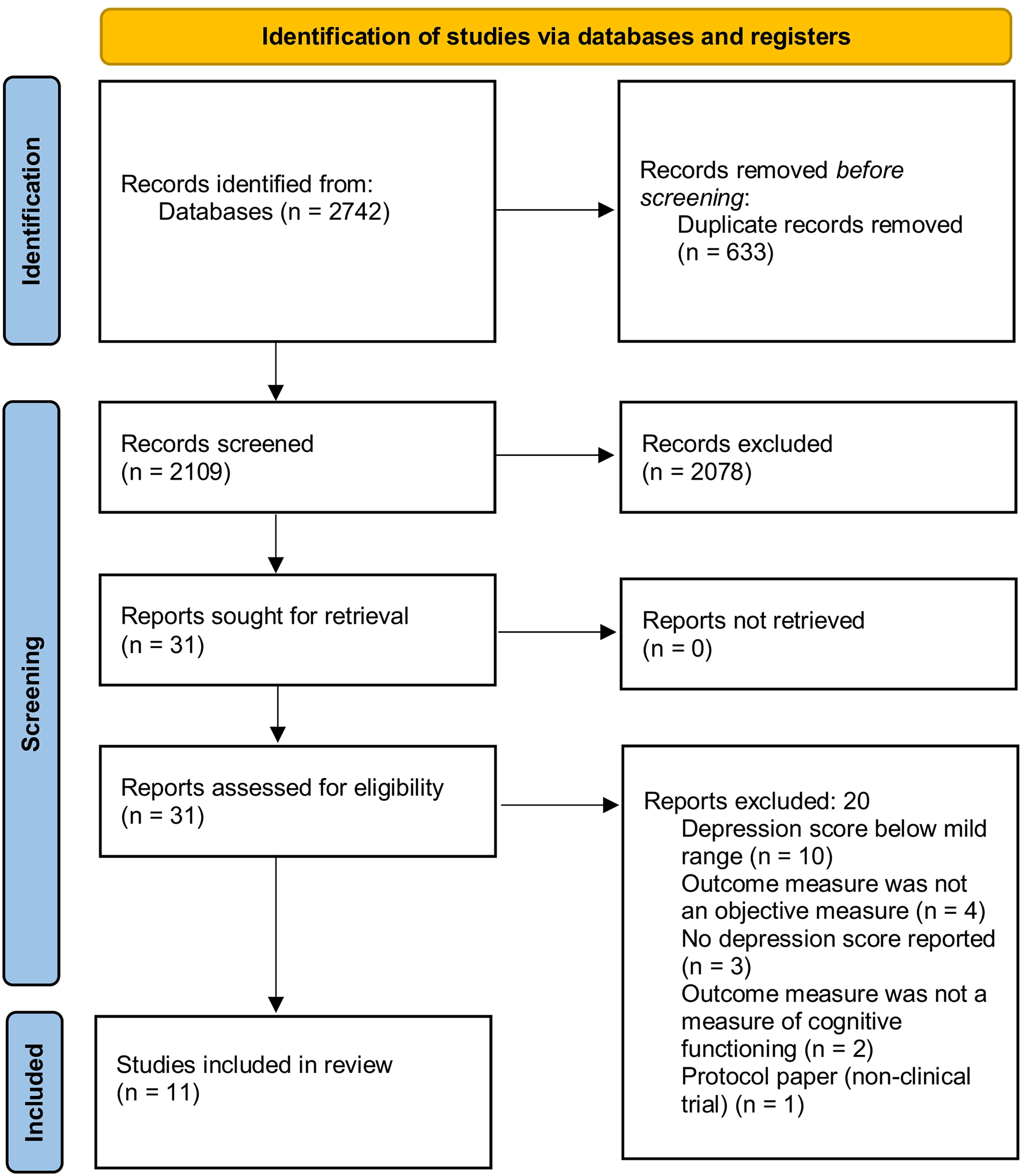

Studies meeting the aforementioned inclusion criteria were included in the qualitative review. See Figure 1 for an overview of the study selection process. Two authors (SJP and MAK) reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion. The first author (MAK) reviewed full text articles for inclusion. Results are presented below and are organized via single arm trials and randomized controlled trials.

Figure 1.

Selection process for review.

Results

The search identified 11 articles (10 separate studies) meeting inclusion criteria. Two articles presented the same objective behavioral neurocognitive data, and were authored by the same researchers, and thus, were reviewed as one study (Schoenberg & Speckens, 2014; Schoenberg & Speckens, 2015). Of the 10 studies, five studies were single arm clinical trials, and five were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Results are presented below in terms of type of study, with the results of single arm trials first, and then results of RCT’s and quasi-experimental studies second. Cognitive measures are identified and described as they were in the individual papers. We have also included the names of the cognitive tests in order to compare across studies. A summary of the results can be found in Table 2 as well.

Table 2.

Overview of studies included in the review in alphabetical order.

| Authors | Treatment (n) | Depression Measure | Mean Pre-Intervention Depression Score | Objective Neuropsychological Measure(s) | Brief Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (2007) | MBSR (39) Control (33) |

BDI | MBSR1: 13.1 Control: 8.1 |

Vigil Continuous Performance Test (The Psychological Corporation); Switching Task; Stroop Paradigm; Object Detection Task | No group differences; No pre-post differences |

| Berk et al. (2018) | MBSR (13) | DASS-21 | MBSR: 12.92 | Verbal Learning Test; Trail Making Test A and B; Symbol Digit Modalities Test adapted | Verbal memory improved from pre-post treatment. No other significant changes noted. |

| Blankespoor et al. (2017) | MBSR (25) | BDI | MBSR: 12.6 | Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Location Learning Test; Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; Digit Span Test; Letter-Number Sequencing Test’ Letter Fluency Test | Less displacement errors on immediate recall of LLT. No other significant changes in cognitive functions. |

| Cash et al. (2016) | MBSR (39) | PHQ-9 | MBSR: 6.36 | Trail Making Test A and B; Digit Span Test; Auditory Consonant Trigrams; Controlled Oral Word Association | No significant changes in cognitive measures when looking at the overall sample. When examining just patients with Parkinson’s Disease (n = 29), significant improvements were found in measures of working memory. |

| Huang et al. (2019) | MBCT (23) | 18 Item Taiwan Depression Scale | MBCT: 23.35 | Numerical Stroop Task | Significantly improved interference on Stroop task. |

| Mallya & Fiocco (2019) | MBSR (22) Control (20) |

CES-D | MBSR: 19.16 Control: 19.13 |

Trail Making Test B; Controlled Oral Work Association; California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd edition; WAIS-IV Digit Span Backwards; WAIS-IV; Mini Mental State Examination | No group differences; No pre-post differences. |

| Sachse et al. (2011) | MBCT (22) | BDI-II | MBCT: 33.95 | Stroop Task; Trail Making Test | Significant improvements pre-post treatment in processing speed and inhibition. |

| Schoenberg & Speckens (2014; 2015) | MBCT (26) Control (24) |

IDS | MBCT: 27.3 Control: 25.1 |

Go/No-Go Task | No group differences; No pre-post differences. |

| Verhoeven et al. (2014) | MBCT (38) Control (16) |

BDI-II | MBCT: 19.0 Control: 15.4 |

Stroop Color/Word Task; Emotional Stroop Task; Sustained Attention to Response Test | MBCT group showed significant increase in inhibition via the emotional Stroop task. No other group or time differences. |

| Wetherell et al. (2017) | MBSR (47) Control (56) |

PROMIS | MBSR: 20.3 Control: 19.9 |

Verbal Fluency Test; Color word Interference Test | Significant improvement in MBCT group in memory composite (driven by immediate memory recall. No other group or time differences. |

only treatment group meets clinical cutoff

adapted interventions, “Mindfulness-based Intervention” 1.5 hours/week for 8 weeks

Single Arm Trials

Berk et al. (2018) studied older adults (N = 13) with memory complaints (but no diagnosis of cognitive impairment). Depression symptoms were measured with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales – Depression Subscale (DASS-21; Henry & Crawford, 2005), and participants had a mean depression score of 12.92 indicating mild depressive symptoms on average. Participants completed an 8-week standard course of MBSR, and completed the NeuroTask online test battery at pre- and post-treatment. NeuroTask includes assessments of verbal memory (Verbal Learning Test; Van der Elst et al., 2005), executive functioning (Trail Making Tests A and B; Reitan & Wolfson, 1993), and information processing speed (adapted Symbol Digit Modalities Test; Smith, 1982). This study found that though many cognitive measures trended towards an increase from pre- to post-treatment, only verbal memory significantly increased from pre- to post-treatment.

Blankespoor et al. (2017) studied adults with a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (N = 25). Depression symptoms were measured via the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996), and participants’ mean depression score prior to initiating treatment was 12.6, indicating mild depression. Participants completed a standard 8-week course of MBSR and several objective cognitive measures including: verbal learning and memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Van der Elst et al., 2005), visuospatial memory (The Location Learning Task; Kessels et al., 2006), information processing speed (Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; Tombaugh, 2006), and working memory and attention (Digit Span Forward and Backward, Letter Number Sequencing; Lezak et al., 2004). Blankespoor et al. (2017) found that after completing the 8-week MBSR course, participants made significantly fewer displacement errors on immediate recall on tests of visuospatial memory (The Location Learning Task). No other cognitive tasks displayed significant changes from pre- to post-treatment.

Cash et al. (2016) studied patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PD; n = 29) and their caregivers (n = 10). Depression symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001), and the whole sample had a pre-treatment mean of 6.36, which is considered mild severity. Participants completed a slightly modified version of MBSR spanning 8-weeks. Modifications from standard MBSR were aimed to make MBSR more comfortable for PD patients and included: reduced duration of in session meditation practice, encouragement to modify meditative techniques such as sitting in a chair or lying down, and additional psychoeducation about the emotional and cognitive effects of PD and the stressors associated with caregiving were presented in the first session. Participants completed neurocognitive measures at pre- and post-treatment including measures of processing speed (Trail Making Test A; Reitan, 1958), basic attention (Digit Span; Wechsler, 2008), complex attention (Auditory Consonant Trigrams; Strauss et al., 2006), and working memory and mental flexibility (Auditory Consonant Trigrams, Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT), Trail Making Test B; Reitan, 1958; Ruff et al., 1996; Strauss et al., 2006). When examining the sample as a whole, there were no significant changes in any cognitive processes from pre- to post-treatment. When the authors examined just the PD patients alone (i.e., excluding the caregivers from the analyses) they found a significant improvement on measures of working memory (COWAT and digit span sequencing) from pre- to post-treatment.

Huang et al. (2019) examined bereaved individuals (N = 23) who had lost a significant relative within 6-months to 4-years of starting the study. Depression was measured via the Taiwan Depression Scale (TDS; Lee et al., 2000), and participants had a mean depression score of 23.35 at baseline, indicating that they met for MDD. Participants completed an 8-week standard MBCT course, and completed the numerical Stroop Task measuring executive control and inhibition at pre- and post-treatment (Stroop, 1935). Results showed a significant reduction in interference reaction time scores on the Stroop, which indicated increased inhibition abilities from pre- to post-treatment.

Sachse et al. (2011) studied patients (N = 22) with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The authors noted that 77.3% of their sample met criteria for current MDD, and 9.1% met criteria for dysthymic disorder. Depression was also assessed via the Beck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996), and participants mean depression score at baseline was 33.95 indicating severe depression symptoms. Participants completed a slightly modified version of the 8-week MBCT in order to address specific needs of the BPD population. Modifications included providing fewer CD recordings for home practice, only included exercises with guided instructions, and provided psychoeducational information about BPD and emotional distress. Cognitive measures examined selective attention and inhibition (Color/Word Stroop; Stroop, 1935), and processing speed and executive functioning (Trail Making Tests A and B, respectively; Lezak et al., 2004; Tombaugh, 2004). Results from this study displayed significant improvements in processing speed as indicated by significant improvement on Trail Making Test A, from pre- to post-treatment. Furthermore, results also showed improvements on executive functioning (inhibition) as indicated by a significant improvement in interference scores on the Stroop Color/Word test.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Anderson et al. (2007) conducted an RCT comparing a standard 8-week course of MBSR (n = 39) vs. an 8-week waitlist control condition (n = 33). Participants were adults recruited from the community. Depression symptoms were measured via the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996), and participants’ mean score at baseline was 13.1 indicating mild levels of depression symptoms. The authors examined several aspects of attentional control including sustained attention (Vigil Continuous Performance Test; for more details see Anderson et al., 2007), attention switching (Computerized Switching Task; for more details see Anderson et al., 2007), inhibition (Stroop Color/Word Test; Stroop, 1935), and non-directed attention (Object Detection Task; Hollingworth & Henderson, 1998). The authors did not find any effects of MBSR from pre- to post-treatment on any of the attentional control measures, nor did they find any differences between treatment groups.

Mallya and Fiocco (2019) studied older (>50 years old) caregivers of people with neurocognitive disorders. Participants were randomly assigned to 8-weeks of standard MBSR (n = 22) or a psychoeducational support group (n = 20). Participants in the MBSR group had baseline depression symptoms score of 19.16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), and the control group had a mean score of 19.13, both indicating mild levels of depression. Participants in both groups completed a battery of cognitive measures pre- and post-treatment including measures of set shifting (Trail Making Test B; Reitan & Wolfson, 1993), verbal fluency (COWAT; Benton, 1989), episodic memory (California Verbal Learning Test-II (CVLT-II); Delis et al., 2000), working memory (Digit Span Backwards; Wechsler, 2008), processing speed (Coding and Symbol Search subtests of the WAIS-V; Wechsler, 2008), and global cognitive functioning (Mini Mental Status Exam; Folstein et al., 1975). Results revealed no significant differences on any of the cognitive measures from pre- to post-treatment, or between treatment groups.

Schoenberg and Speckens (2014) and Schoenberg and Speckens (2015) studied participants with MDD, and a baseline mean depression score of 27.3 on the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS; Rush et al., 1996), indicating moderate to severe depression. The authors presented data examining the effects of standard MBCT (n = 26) vs. a waitlist control (n = 24) on a number of EEG indices. In addition to the EEG data, Schoenberg & Speckens (2014, 2015) also examined cognitive inhibition (Affective Go/No Go Task; See Schoenberg & Speckens, 2014 & 2015 for more details). The results did not reveal any significant differences from pre- to post-treatment on inhibition, nor did it reveal differences in inhibition between groups.

Verhoeven et al. (2014) studied the effects of MBCT (n = 38) vs. a waitlist control (n = 16) on several objective measures of executive function and attention in a group of remitted depressed patients who had previously met criteria for MDD, but were not currently experiencing a major depressive episode. The authors subscribed to theories that posit that depressed individuals, and individuals with remitted depression show negative attentional biases (De Raedt & Koster, 2010; Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). As such, the authors focused on various aspects of executive functioning including attention and inhibition measures, utilizing negatively biased stimuli. Assessed via the Dutch version of the Beck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996; Van der Does, 2002), participants in the MBCT group had a baseline mean depression score of 19, and participants in the control group had a baseline mean depression score of 15.4, indicating that both groups were in the range for mild depressive symptoms. Objective cognitive measures were administered at pre- and post- treatment in the MBCT group, and at baseline and 8-weeks in the control group. Cognitive constructs examined were response inhibition (Stroop Color/Word Test; Stroop, 1935) affective response inhibition (Emotional Word Stroop Task; Vrijsen et al., 2014), and sustained attention (Sustained Attention to Response Test; SART; Manly et al., 2000).

Results indicated no significant time or group effects on response inhibition, nor on sustained attention. However, results indicated a significant group by time interaction on affective response inhibition. Specifically, results revealed that compared to the control group, participants in the MBCT group showed greater decrease in reaction time for depression specific words and to neutral words post-treatment. Both groups showed faster reaction time for anxiety specific words from baseline to 8-week assessment. The authors also noted that the decreases in reaction time for the depressive and neutral words did not correlate with a decrease in BDI-II scores, which indicated that these effects were likely not due to a decrease in overall depression symptoms.

Wetherell et al. (2017) studied older adults with clinically significant anxiety or depressive symptoms and with subjective reports of age-related neurocognitive problems. Wetherell et al. (2017) subscribed to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) theory in that they proposed that MBSR may have correcting effects on the HPA axis in depressed adults, which then consequently could benefit neurocognition. Participants were randomly assigned to receive a standard 8-week course of MBSR (n = 47) or a health education control class (n = 56). Participants’ mean baseline depressive symptoms were clinically significant for mild depression according to the PROMIS Depression scale (M = 20.0). Participants completed cognitive measures examining verbal learning and memory (Immediate Recall List, Immediate Recall Story, Delayed Recall List, Delayed Recall Story; Van der Does, 2002; Wechsler, 1987) and cognitive control including verbal fluency (D-KEFS Verbal Fluency Test; Delis et al., 2001) and inhibition (Stroop Color/Word Test; Stroop, 1935). The authors summarized their results by computing composite scores for memory and cognitive control variables. Results indicated that compared to the control group, participants in the MBSR group showed an improvement in the memory composite from pre- to post-treatment, and this was driven by an improvement in immediate memory recall of a list. There were no other significant group-by-time interactions.

Discussion

Results from the current review study are consistent with previous reviews which examined the effects of MBSR and MBCT on cognition in healthy individuals. Specifically, across the 10 studies included in this review with participants with at least mild symptoms of depression, it appears that results are variable with regard to MBSR’s and MBCT’s effects on cognitive functions as measured by objective, measures. While 3 studies found no effects on any cognitive skills, 7 studies found at least one improvement. Specifically, three studies found improvements in aspects of memory (Berk et al., 2018; Blanekespoor et al., 2017; Wetherell et al., 2017). Two studies found improvements in inhibition (Huang et al., 2019; Sasche et al., 2011), and one study found improvement in working memory when examining a subsample of the larger study sample (Cash et al., 2016). One study examined affective inhibition (i.e., using an emotionally laden inhibition task), and found that compared to controls, participants in MBCT showed increased skills in inhibition of depressogenic and neutral words.

Whereas all 5 single arm trials showed at least one improvement in cognitive functioning from pre- to post-treatment, only 2 of 5 RCTs showed significant effects for MBSR or MBCT. Therefore, it is still unclear whether improvements in cognitive functioning are due to the treatment effects of MBCT/MBSR, or whether these effects could be due to other factors such as the passage of time, practice effects, or a decrease in depression symptoms. Furthermore, all studies (single arm trials and RCT’s) reported data collected from two timepoints: before treatment started and after treatment was complete. While pre-post treatment designs are common, additional information regarding the time course and potential varying effects could be examined if studies included additional assessments throughout MBSR and MBCT. This would provide more thorough and more clear examination of the potential effects of MBSR and MBCT on cognition.

This review also highlights some inconsistencies in the research. For example, some studies refer to measures of “attention control” encompassing tasks such as sustained attention, attention switching, inhibition, non-directed attention (e.g., Anderson et al., 2007) and other studies do not use the term attention control but do utilize measures of inhibition, and selective attention, among others (e.g., Sachse et al., 2011). Furthermore, the research is inconsistent in that many studies use different terminology to describe and measure similar cognitive constructs. Extant literature has demonstrated that aspects of executive functioning are multifaceted and distinct processes (e.g., Miyake et al., 2000). While some studies breakdown executive functioning into components, such as working memory, shifting, and inhibition, other studies refer to the broad domain of executive functioning. Therefore, it may be important for researchers in MBSR and MBCT to agree upon core cognitive measures to include in future research in order to better streamline and compare studies.

One helpful tool to help streamline the cognitive measures to include in future work may be the NIH Toolbox for the Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function (Weintraub et al., 2013). This toolbox was developed to examine cognitive subdomains important for health including executive function, episodic memory, language, processing speed, working memory, and attention (Weintraub et al., 2013). Another limitation to summarizing this literature is the difference in the samples. Studies examined individuals with multiple sclerosis (Blankespoor et al., 2017), with Parkinson’s Disease (Cash et al., 2016), or older adults (Berk et al., 2018). Only 3 studies specifically selected participants with elevated depression symptoms; that is, most studies were not specifically focused on whether and how MBSR or MBCT alleviated clinically significant depression symptoms. It is possible that a more robust response may be detected if studies were limited to people with clinically significant depression symptoms. Therefore, it is likely that the varied patient samples could impact many aspects including cognitive functioning at baseline, as well as interact with post-treatment effects of MBSR or MBCT.

Overall, the review of the literature examining the cognitive effects of MBSR and MBCT in the context of depression, indicated several inconsistencies in the research. Inconsistencies may be due to a lack of consensus on what specific aspects of cognitive functioning may be important to examine, what specific measures to use, and under what conditions or context to measure cognition (i.e., neutral vs. emotional). For individuals with depression symptoms, it may be particularly important to examine cognitive functioning in the context of affectively-laden cognitive tasks (Koster et al., 2017). Indeed, Verhoeven et al. (2014) found that response inhibition as measured by the emotional Stroop task, improved for participants in MBCT, but not those in the control group. As such, it is possible that MBCT may exert its effects on these depressogenic cognitive styles, rather than neutral cognitive functioning. Future research should continue to examine cognitive skills in the context of emotion when examining MBCT and MBSR’s effects on cognition

Acknowledgments:

This work was funded by the National Center for Complimentary and Integrative Health Grant #: F32AT010560 (PI: Kraines)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This AM is a PDF file of the manuscript accepted for publication after peer review, when applicable, but does not reflect post-acceptance improvements, or any corrections. Use of this AM is subject to the publisher’s embargo period and AM terms of use. Under no circumstances may this AM be shared or distributed under a Creative Commons or other form of open access license, nor may it be reformatted or enhanced, whether by the Author or third parties. See here for Springer Nature’s terms of use for AM versions of subscription articles: https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/policies/accepted-manuscript-terms

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Uebelacker’s spouse is employed by Abbvie Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards:

This manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

References

References marked with an * are included in the systematic review.

- *.Anderson ND, Lau MA, Segal ZV, & Bishop SR (2007). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attention control. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 14, 449–463. doi: 10.1002/cpp.544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T & Olatunji BO (2012). Eye tracking of attention in the affective disorders: A meta-analytic review and synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(8), 704–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MP, Mitchell P, & Goodwin GM (2001). Cognitive deficits in depression: Possible implications for functional neuropathology. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(3), 200–206. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). BDI-II: Beck depression Inventory Manual. San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL (1989). Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa City: AJA Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Berk L, Hotterbeekz R, van Os J, & van Boxtel M (2018). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in middle-aged and older adults with memory complaints: a mixed-methods study. Aging & Mental Health, 22(9), 1107–1114. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1347142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Blankespoor RJ, Schellekens MPJ, Vos SH, Speckens AEM, & de Jong BA (2017). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychological distress and cognitive functioning in patients with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mindfulness, 8(5), 1251–1258. doi: 10.1007/s12571-017-0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cash TV, Ekouevi VS, Kilbourn C, & Lageman SK (2016). Pilot study of a mindfulness-based group intervention for individuals with Parkinson’s Disease and their caregivers. Mindfulness, 7, 361–371. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0452-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Calati R, & Serretti A (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology review, 31(3), 449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.22.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, & Kramer JH (2001). Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer J, & Ober B (2000). California Verbal Learning Test-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- De Lissnyder E, Koster EHW, Derakshan N, & De Raedt R (2010). The association between depressive symptoms and executive control impairments in response to emotional and non-emotional information. Cognition and Emotion, 24(2), 264–280. [Google Scholar]

- De Raedt R, & Koster EH (2010). Understanding vulnerability for depression from a cognitive neuroscience perspective: A reappraisal of attentional factors and a new conceptual framework. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 10, 50–70. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.1.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PB, Laird AR, Maller J, & Daskalakis ZJ (2008). A meta-analytic study of changes in brain activation in depression. Human Brain Mapping, 29(6), 683–695. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjorback LO, Arndt M, Ornbol E, Fink P, & Walach H (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy – a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119. Doi: 10/1111.j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH & Joormann J (2010). Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 285–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, & Kessler RC (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A, Watkins E, Mansell W, & Shafran R (2004). Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD & Crawford JR (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth A & Henderson JM (1998). Does consistent scene context facilitate object perception? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 127(4), 398–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Huang FY, Hsu AL, Hsu L,M, Tsai JS, Huang CM, Chao YP, Hwang TJ, & Wu CW (2019). Mindfulness improves emotion regulation and executive control on bereaved individuals: an fMRI study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 541. doi: 10/3389/fnhum.2018.00541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J & Gotlib IH (2008). Updating the contents of working memory in depression: Interference from irrelevant negative material. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(1), 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Yoon KL, & Zetsche U (2007). Cognitive inhibition and depression. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 12(3), 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels RP, Nys GM, Brands AM, van der Berg E, & Van Dandvoort MJ (2006). The modified Location learning test: norms for the assessment of spatial memory function in neuropsychological patients. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(8), 841–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster EHW, Hoorelbeke K, Onraedt T, Owens M, & Derakshan N (2017). Cognitive control interventions for depression: A systematic review of findings from training studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S, Kissane D, & Meadows G (2016). Cognitive effects of MBSR/MBCT: A systematic review of neuropsychological outcomes. Consciousness and Cognition, 45, 109–123. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2016.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Yang MJ, Lai TJ, Chiu NM, & Chau TT (2000). Development of the Taiwanese depression questionnaire. Chang Gung Medical Journal, 23, 688–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levens SM & Gotlib IH (2010). Updating positive and negative stimuli in working memory in depression. Journal of Experimental Psychology, General, 139(4), 654–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, & Loring DW (2004). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma SH & Teasdale JD (2004). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 31–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006.X.72.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mallya S & Fiocco AJ (2019). The effects of mindfulness training on cognitive and psychosocial well-being among family caregivers of persons with neurodegenerative disease. Mindfulness, 10(44). 2026–2037. doi: 10.1007/s12671-019-01155-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manly T, Davison B, Heutink J, Galloway M, & Robertson I (2000). Not enough time or not enough attention?: Speed, error and self-maintained control in the Sustained Attention to Response Test (SART). Clinical Neuropsychological Assessment, 3, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A & MacLeod C (2005). Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 167–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, & Wager TD (2000) The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41, 49–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motter JN, Pimontel MA, Rindskopf D, Devanand DP, Doraiswamy MP, & Sneed JR (2016). Computerized cognitive training and functional recovery in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 189(1), 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu M, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, … Moher D (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372: n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham AD, McHugh RK, & Otto MW (2010). A meta-analysis of the magnitude of biased attention in depression. Depression and Anxiety, 27(12), 1135–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM (1958). Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R, & Wolfson D (1993). The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical applications. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, & Blackwell AD (2014). Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 44(10), 2029–2040. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Kasai K, Kogi M, Fukuda R Iwanami A, Nakagome K et al. (2004). Executive and prefrontal dysfunction in unipolar depression: A review of neuropsychological and imaging evidence. Neuroscience Research, 50, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff RM, Light RH, Parker SB, & Levin HS (1996). Benton Controlled Coral Word Association Test: reliability and updated norms. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 11, 329–338. doi: 10.1093/arclin/11.4.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, & Trivedi MH (1996). The inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine, 26, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sachse S, Keville S, & Feigenbaum J (2011). A feasibility study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory Research and Practice, 84, 184–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Schoenberg PLA & Speckens AEM (2014). Modulation of induced frontocentral theta (FM-0) event related (de-)synchronization dynamics following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in major depressive disorder. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 8(5), 373–388. doi: 10.1007/s11571-014-9294-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Schoenberg PLA & Speckens AEM (2015). Multi-dimensional modulations of α and Υ cortical dynamics following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in major depressive disorder. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 9(1), 13–29. doi: 10/1007/s11571-014-9308-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, & Teasdale JD (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A (1982). Symbol Digits Modalities Test. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR (2013). Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: A meta-analysis and review. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 81–132. doi: 10.1037/a0028727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Sherman EMS, & Spreen O (Eds.). (2006). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, & Pettman D (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of anxiety or depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 9(4), e96110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643–662. doi: 10.1037/h0054651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN (2004). Trail Making Test A an dB: Normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 19, 203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN (2006). A comprehensive review of the paced auditory serial addition test (PASAT). Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(1), 53–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD (1988). Cognitive vulnerability to persistent depression. Cognition and Emotion, 2(3), 247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Segal ZV., Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, & Lau MA (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 615–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does JW (2002). The Dutch version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II-NL).Second edition. Lisse: Swets Test Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Elst W, Van Boxtel MPJ, Van Breukelen GJP, & Jolles J (2005). Rey’s verbal learning test: Normative data for 1855 healthy participants aged 24–81 years and the influence of age, sex, education, and mode of presentation. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 11(3), 290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Verhoeven JE, Vrijsen JN, van Oostrom I, Speckens AEM, & Rinck M (2014). Attention effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in formerly depressed patients. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 5(4), 414–424. doi: 10.5127/jep.037513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijsen JN, van Oostrom I, Isaac L, Becker ES, & Speckens A (2014). Coherence between attentional 363 and memory biases in sad and formerly depressed individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38, 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1987). Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2008). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV): technical and interpretive manual (4th ed.). San Antonio, TX: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ, Carlozzi NE, Slotkin J, Blitz D, Wallner-Allen K, Fox NA, Beaumont JL, Mungas D, Nowinski CJ, Richler J, Deocampo JA, Anderson JE, Manly JJ, Borosh B, Havlik R, … Gershon RC (2013). Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S54–S64. doi: 10/1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wetherell JL, Hershey T, Hickman S, Tate SR, Dixon D, Bower ES, & Lenze EJ (2017). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for older adults with stress disorders and neurocognitive difficulties: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(7), e734–e743. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer AJ & Banich MT (2007). Inhibition versus switching deficits in different forms of rumination. Psychological Science, 18(6), 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco BE (2009). Depressive cognition: self-reference and depth of processing. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]