Abstract

ShaA (sodium/hydrogen antiporter, previously termed YufT [or NtrA]), which is responsible for Na+/H+ antiporter activity, is considered to be the major Na+ excretion system in Bacillus subtilis. We found that a shaA-disrupted mutant of B. subtilis shows impaired sporulation but normal vegetative growth when the external Na+ concentration was increased in a low range. In the shaA mutant, ςH-dependent expression of spo0A (PS) and spoVG at an early stage of sporulation was sensitive to external NaCl. The level of ςH protein was reduced by the addition of NaCl, while the expression of spo0H, which encodes ςH, was little affected, indicating that posttranscriptional control of ςH rather than spo0H transcription is affected by the addition of NaCl in the shaA mutant. Since this mutant is considered to have a diminished ability to maintain a low internal Na+ concentration, an increased level of internal Na+ may affect posttranscriptional control of ςH. Bypassing the phosphorelay by introducing the sof-1 mutation into this mutant did not restore spo0A (PS) expression, suggesting that disruption of shaA affects ςH accumulation, but does not interfere with the phosphorylation and phosphotransfer reactions of the phosphorelay. These results suggest that ShaA plays a significant role at an early stage of sporulation and not only during vegetative growth. Our findings raise the possibility that fine control of cytoplasmic ion levels, including control of the internal Na+ concentration, may be important for the progression of the sporulation process.

All living cells actively extrude sodium ions and maintain an inwardly directed gradient of sodium concentration (33). Sodium extrusion is important as a detoxification process, because internal sodium inhibits many metabolic activities when present at high concentrations (29, 41). The major Na+-extruding mechanism in most bacterial cells is the Na+/H+ antiporter, which extrudes Na+ in exchange for H+ (32, 42). This process is driven by an electrochemical gradient of proton across the cytoplasmic membrane, which is established by the respiratory chain or the H+-translocating ATPase (55). Besides its role in Na+ extrusion, the Na+/H+ antiporter plays important roles in pH homeostasis (3, 32), cell volume regulation (17), and establishment of an electrochemical potential of Na+ (33).

Most of the Na+/H+ antiporters reported to date are encoded by single genes (6, 26, 27, 39, 44, 49, 52, 53). However, recent reports have demonstrated the existence of a novel type of cation/H+ antiporters usually encoded by a cluster of seven genes (20, 25, 45). Hiramatsu et al. (20) have recently reported the features of the mnh (multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter) locus encoding an Na+/H+ antiporter in Staphylococcus aureus. All seven genes (mnhA to mnhG) are required for the antiporter activity, suggesting that the Mnh antiporter consists of seven kinds of subunits and forms a huge ion transport complex. Homologues of the mnh locus have been found in alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain C-125, Rhizobium meliloti, and Bacillus subtilis. These may be considered to be members of a multisubunit antiporter family. This gene family was first discovered in alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain C-125 (18). The homologue first identified in Bacillus sp. strain C-125 is related to the Na+/H+ antiporter and is required for pH homeostasis in an alkaline environment (18). The pha (pH adaptation) locus of R. meliloti contains a whole set of the seven corresponding genes and is required for invasion of nodule tissue to establish nitrogen-fixing symbiosis (45). pha mutants show sensitivity to K+, but not to Na+, in their growth and are deficient in diethanolamine-induced K+ efflux (45). It seems that the pha locus in R. meliloti may encode a K+/H+ antiporter which is involved in pH adaptation during the infection process (45).

A whole set of the seven genes has also been found in the gram-positive endospore-forming B. subtilis (25). We have recently shown that disruption of the first gene, yufT, results in a decrease in Na+/H+ antiporter activity and impaired growth when the external sodium concentration is increased, indicating that yufT encodes a Na+/H+ antiporter which has a dominant role in the extrusion of cytotoxic sodium (31). Ito et al. have more recently shown that the same set of seven genes is transcribed as an operon and that the operon is responsible for cholate resistance and pH homeostasis as well as sodium resistance (25).

Endospore formation in B. subtilis has been extensively studied at the molecular level as a simple model system with which to understand cellular differentiation. Only a few studies have focused on the role of ions or ion transport in sporulation of B. subtilis. Mn2+ and Fe2+ are known to be essential for sporulation (5, 13), and transport of Mn2+ and Ca2+ is activated during sporulation (46). It has been shown as well that the activities of several proteins related to sporulation, including KinA (16), SpoIIE (11), and RapB (51), are dependent on divalent cations. However, little is known about the role of monovalent cations in sporulation. In the present study, we found that disruption of yufT leads to a diminished Na+ excretion capacity (31), which entails sporulation defects, when the external sodium concentration is increased. To identify the stage at which the function of the Na+/H+ antiporter is required, we examined the expression of early sporulation genes in the yufT mutant, and our findings suggest the possibility that intracellular Na+ levels may play a role in posttranscriptional regulation of ςH, an alternative sigma factor required for an initial process in the course of sporulation in B. subtilis. This report is the first to provide evidence of a relationship between Na+ and sporulation in B. subtilis.

We have previously proposed renaming yufT as ntrA (Na+ transporter) (31). However, to avoid confusion with ntr of nitrogen regulation, we have again renamed the operon by including yufT as sha (sodium/hydrogen antiporter).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were derived from UOT1285, used as the wild-type strain in our laboratory. The shaA::neo allele contains a neomycin-resistant cassette inserted into the EcoRV site in shaA as described previously (31).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| UOT1285 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 | Laboratory stock |

| SK6 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 shaA::neo | This study |

| RIK10 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 amyE::spo0A (PS)-bgaB cat | 38 |

| RIK51 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 amyE::spoVG-bgaB cat | 1 |

| RIK50 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 amyE::spo0H-bgaB cat | 38 |

| SK610 | SK6 amyE::spo0A (PS)-bgaB cat | SK6 DNA→RIK10a |

| SK651 | SK6 amyE::spoVG-bgaB cat | SK6 DNA→RIK51a |

| SK650 | SK6 amyE::spo0H-bgaB cat | SK6 DNA→RIK50a |

| RIK62 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 sof-1 spo0FΔS amyE::spo0A (PS)-bgaB cat | This study |

| SK662 | trpC2 lys 1 aprEΔ3 nprE18 nprR2 sof-1 spo0FΔS amyE::spo0A (PS)-bgaB cat shaA::neo | SK6 DNA→RIK62a |

RIK10, RIK51, RIK50, and RIK62 were each transformed with chromosomal DNA from strain SK6 to construct SK610, SK651, SK650, and SK662, respectively.

B. subtilis cells were routinely cultivated in LB1/2 (10 g of Difco tryptone, 5 g of Difco yeast extract, and 5 g of NaCl per liter [pH 7.0]) in the case of shaA+ strains or LBK1/2 (10 g of Difco tryptone, 5 g of Difco yeast extract, and 5 g of KCl per liter [pH 7]) in the case of shaA mutant strains. Neomycin (7.5 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) were added for selection when necessary. The nutrient sporulation medium used was modified 2× SG medium [16 g of Difco nutrient broth per liter, 1 g of KCl per liter, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM Ca(NO3)2, 1 μM FeSO4, 10 μM MnCl2, 1 g of glucose per liter] (34). S7K minimal sporulation medium supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) glucose is identical to S7 medium (14), except that sodium glutamate was replaced with potassium glutamate. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 660 nm (OD660).

Transformation of B. subtilis.

Competent B. subtilis cells were prepared and transformed by the method previously described (10). When isolating shaA::neo strains, cells were grown in modified CI (CIK) medium [14 g of K2HPO4 per liter, 6 g of KH2PO4 per liter, 2 g of (NH4)2SO4 per liter, 1 g of tripotassium citrate dihydrate per liter, 5 mM MgSO4, 5 g of glucose per liter, 50 μg of l-tryptophan per ml, 50 μg of l-lysine per ml, 1 g of yeast extract per liter] until early stationary phase. A 0.5-ml portion of the culture was centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of modified CII (CIIK) medium [14 g of K2HPO4 per liter, 6 g of KH2PO4 per liter, 2 g of (NH4)2SO4 per liter, 1 g of tripotassium citrate dihydrate per liter, 5 mM MgSO4, 5 g of glucose per liter, 25 μg of l-tryptophan per ml, 25 μg of l-lysine per ml, 0.5 g of yeast extract per liter]. A 0.1-ml portion of the suspension of competent cells was mixed with DNA and incubated at 37°C for 90 min with shaking. Then, 0.3 ml of CIK medium was added, and the mixture was further incubated for 60 min. An appropriate volume of the culture was then spread on a CIK plate containing 7.5 μg of neomycin per ml.

Assay of spore formation.

Cells were grown in 2× SG medium, and spores were assayed 22 h after the end of the exponential phase (T22). The number of viable cells per ml of culture was determined as the total number of CFU on LB1/2 (shaA+ strains) or LBK1/2 (shaA mutant strains) plates. The number of spores per ml of culture was determined as the number of CFU after heat treatment (80°C, 10 min).

Assay of β-galactosidase activity.

The expression of transcriptional bgaB fusions was monitored by measuring thermostable β-galactosidase activity (21, 22). Cells were grown in 2× SG medium, and 50- to 500-μl samples of the cultures were removed at appropriate times for the assay. The cell pellets were toluenized in 0.5 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). After preincubation at 62°C, reactions were started by adding 0.2 ml of 4 mg of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside (ONPG) per ml to the samples and stopped by adding 0.5 ml of 1 M Na2CO3. After centrifugation, the A420 of the supernatants was measured. The specific activity was expressed as 1,000 × (A420 per min of incubation per ml of culture per OD660 unit).

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed as described by Asai et al. (2). Cells were grown in 2× SG medium, and the same amount of cells (the culture volume × OD660 = 5) was collected in each instance at appropriate times. The cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 g of glycerol per liter, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mg of lysozyme per ml [pH 7]) and incubated at 37°C for 6 min to allow cell lysis to occur. Then, 1.5 μl of lysis buffer B (330 mM MgCl2, 6.6 mg of DNase I per ml, 16.6 mg of RNase A per ml) was added, and the mixture was further incubated for 6 min. Aliquots of the whole-cell extracts (15 μg of total protein) were diluted in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and subjected to electrophoresis on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. Thereafter, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) by using a Mini Trans-Blot transfer cell (Bio-Rad) in a semidry condition. The blotted membrane was incubated with primary anti-ςH antibody (2) and secondary goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma) and finally reacted with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) and nitroblue tetrazolium salt (both supplied by Boehringer Mannheim) to detect signals.

RESULTS

Sporulation of the shaA mutant is impaired with an increase in external sodium concentration.

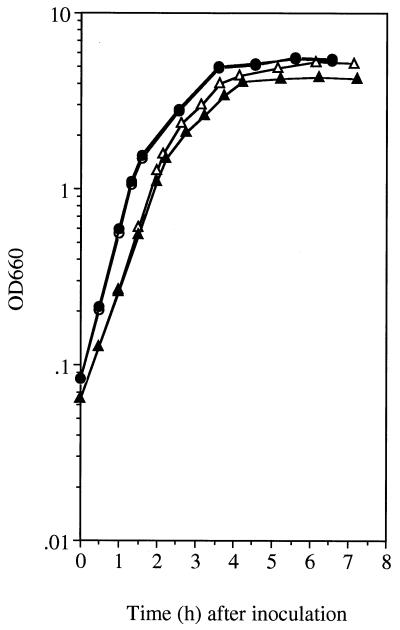

As shown previously, the shaA-disrupted strain shows diminished Na+/H+ antiport activity and impaired growth when the external NaCl concentration was increased, and it is therefore considered to have a diminished Na+ excretion capacity (31). A 2× SG sporulation medium containing 0.1% glucose was found to have a pH of 6.2 to 6.4, and it contained 18 mM Na+ as a contaminant, as determined by atomic absorption analysis. Under these conditions, SK6, a shaA-disrupted derivative of UOT1285, grew exponentially at a rate almost equal to that of the wild type, as shown in Fig. 1. This finding was consistent with results reported previously (31). As shown in Table 2, the numbers of viable cells at T22 were the same when comparing SK6 and the wild type (both ∼108 cells/ml). The number of spores formed at T22, however, was somewhat lower in the case of SK6 (∼107 spores/ml) than that of the wild type (∼108 spores/ml), as shown in Table 2. When 30 mM NaCl was added to the medium, sporulation of SK6 was severely affected, resulting in less than 10 spores per ml (Table 2), whereas vegetative growth of SK6 was little affected (Fig. 1). On the other hand, addition of NaCl at concentrations up to 200 mM affected neither vegetative growth nor sporulation of the wild type (Table 2) (some data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Growth in 2× SG medium containing 0.1% glucose. Strains UOT1285 (shaA+ [circles]) and SK6 (shaA::neo [triangles]) were grown at 37°C in the absence (open symbols) and presence (solid symbols) of 30 mM NaCl. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD660.

TABLE 2.

Sporulation of the shaA mutant and the wild type

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Mediuma | No. (CFU/ml) of:

|

Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viable cells | Spores | ||||

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | 2× SG | 1.3 × 109 | 5.3 × 108 | 41 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | 2× SG + 30 mM NaCl | 7.8 × 108 | 5.0 × 108 | 64 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | 2× SG + 50 mM NaCl | 7.7 × 108 | 5.5 × 108 | 71 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | 2× SG | 5.2 × 108 | 1.1 × 107b | 2.1 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | 2× SG + 30 mM NaCl | 4.5 × 108 | <10 | <2 × 10−6 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | 2× SG + 50 mM NaCl | 1.4 × 108 | <10 | <7 × 10−6 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | S7K | 3.6 × 108 | 2.5 × 108 | 69 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | S7K + 20 mM NaCl | 3.6 × 108 | 2.1 × 108 | 58 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | S7K + 50 mM NaCl | 3.4 × 108 | 2.0 × 108 | 59 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | S7K + 100 mM NaCl | 4.1 × 108 | 2.0 × 108 | 49 |

| UOT1285 | shaA+ | S7K + 50 mM KCl | 3.0 × 108 | 2.7 × 108 | 90 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | S7K | 3.0 × 108 | 1.1 × 108 | 37 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | S7K + 20 mM NaCl | 3.2 × 108 | 3.5 × 107 | 11 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | S7K + 50 mM NaCl | 1.1 × 107 | 6.8 × 105 | 6.2 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | S7K + 100 mM NaCl | 1.5 × 107 | 5.0 × 10 | 2.9 × 10−4 |

| SK6 | shaA::neo | S7K + 50 mM KCl | 2.2 × 108 | 1.3 × 108 | 59 |

The 2× SG liquid medium (0.1% glucose) contains 18 mM contaminating Na+. The S7K liquid medium (0.1% glucose) contains less than 1 mM contaminating Na+.

The spore production fluctuated between 105 and 107.

We considered that 18 mM Na+ present as a contaminant in the 2× SG medium may have weakly inhibited the sporulation of SK6. In order to eliminate the effect of the contaminating Na+, the sporulation of SK6 was also examined in S7K medium, which contained less than 1 mM Na+ as a contaminant. SK6 produced 108 spores per ml, the same level as that of the wild type, in S7K medium without added NaCl. The sporulation of SK6 was clearly impaired when the external NaCl concentration was increased. When 50 mM NaCl was added to S7K medium, the SK6 cells reached stationary phase at a lower cell density (∼107 cells per ml versus ∼108 cells per ml without NaCl), and produced 105 spores per ml, 1,000-fold less than that in the absence of added NaCl. Moreover, the addition of 100 mM NaCl severely blocked the sporulation of SK6 (Table 2). The effect of the added NaCl on SK6 sporulation was apparently due to the increase in Na+ concentration, rather than being a nonspecific effect of increased ionic strength and/or increased osmolarity, because 50 mM KCl had no effect on sporulation (Table 2) and 25 mM Na2SO4 reduced the spore titer to ∼105 per ml, the same level as that observed in the presence of 50 mM NaCl (data not shown). The effect of NaCl on sporulation of SK6 was more severe in 2× SG medium than in S7K medium. Both 2× SG medium with 30 mM NaCl added and S7K medium with 50 mM NaCl contain ∼50 mM Na+; however, SK6 produced less than 10 spores in the former and ∼105 spores in the latter.

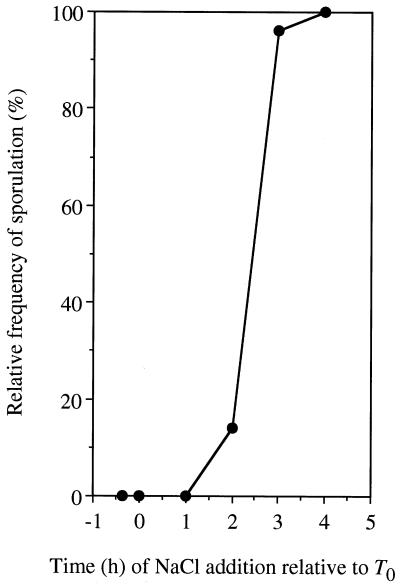

The primary environmental signal for initiation of sporulation is nutrient depletion (12). The severe effects on sporulation are often linked to a decrease in growth rate or growth yield. The vegetative growth rate of SK6 was little affected by the addition of 30 mM NaCl (Fig. 1), but we cannot exclude the possibility that the cells do not fully metabolize components of the medium that may act as inhibitors of sporulation. To exclude this possibility, we examined whether the sporulation of SK6 is inhibited by NaCl when added after the end of exponential growth (T0). SK6 cells were grown in 2× SG medium without added NaCl, and NaCl was added at a final concentration of 30 mM at the times indicated in Fig. 2. The sporulation of SK6 was severely inhibited by NaCl when added just at T0 or before T3 (3 h after the end of exponential growth), but was not affected when added at T3 and after. These results clearly indicate that the addition of 30 mM NaCl specifically affects sporulation events in SK6 which precede T3, but not vegetative growth.

FIG. 2.

Effect of NaCl on sporulation of a shaA::neo strain. SK6 (shaA::neo) cells were grown in 2× SG medium containing 0.1% glucose without added NaCl, and 30 mM NaCl was added to the medium at the indicated times after the end of exponential growth (T0). Relative frequency of sporulation is the spore production per milliliter relative to that of SK6 when grown in 2× SG without added NaCl (4.8 × 106 spores/ml).

In 2× SG medium with 30 mM NaCl added, freshly isolated SK6 produced less than 10 spores, but the strain produced 104 to 106 spores under the same conditions after the cells had been repeatedly cultured on LBK1/2 (including 7.5 μg of neomycin per ml) plates. There is a possibility that additional mutations occurred in the repeatedly cultured SK6 cells. Thus, we always used cells freshly prepared from a stock culture of this strain in the following experiments.

Induction of spo0A (PS) expression at the onset of sporulation is blocked by external NaCl in the shaA mutant.

Whether or not B. subtilis cells initiate sporulation is believed to be decided by the intracellular level of the phosphorylated form of Spo0A (Spo0A-P), which is the key transcription factor that regulates early sporulation genes positively or abrB negatively (23). Phosphorylation of Spo0A occurs through a multicomponent phosphorelay that involves three sensor kinases (KinA, KinB, and KinC), a response regulator (Spo0F), and a phosphotransferase (Spo0B) (4). Transcription of spo0A is regulated by two promoters, PV and PS, which are, respectively, recognized by E-ςA during vegetative growth and by E-ςH at an early stage of sporulation (7). Transcription of spo0A from the PS promoter also requires its own product, Spo0A-P (47). Since sporulation of SK6 was impaired when the external Na+ concentration was increased, it seemed likely that one or more steps in the sporulation process may become sensitive to Na+. We first examined the effect of the disruption of shaA on the expression of spo0A from PS at the time of the onset of sporulation.

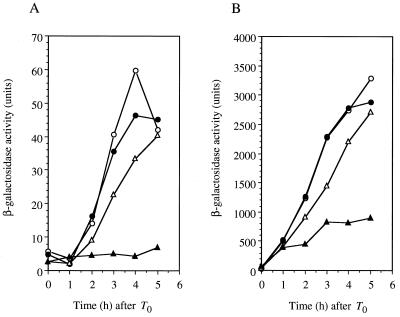

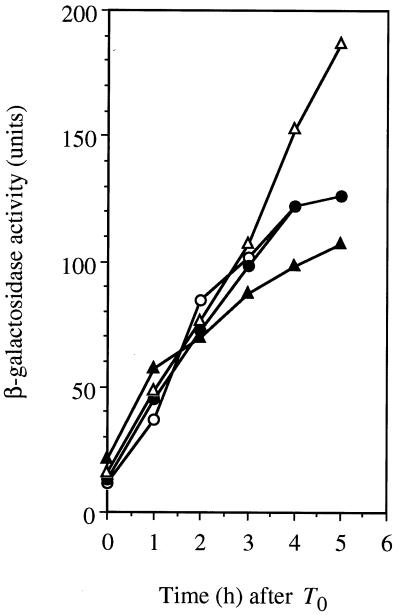

As shown in Fig. 3A, transcription of spo0A from PS was induced in the wild type 1 h after T0 in the presence or absence of 30 mM NaCl. On the other hand, in the absence of 30 mM NaCl, the rate of spo0A (PS) induction was lower in the shaA mutant than that of the wild type. Moreover, spo0A (PS) induction was almost completely blocked in the shaA-disrupted mutant by the addition of 30 mM NaCl. The expression of spo0A (PS) in the shaA mutant was also blocked by 30 mM NaCl when added just at T0, the same as when the mutant was grown in 2× SG with 30 mM NaCl (data not shown). It is, therefore, most likely that the shaA mutation blocks spore development by affecting the formation of Spo0A-P and/or the active ςH-containing RNA polymerase at an early stage of sporulation.

FIG. 3.

Expression of ςH-dependent genes in shaA+ (RIK10 and RIK51) and shaA::neo (SK610 and SK651) strains using the bgaB gene coding for a heat-stable β-galactosidase as a reporter. Cells of shaA+ (circles) and shaA::neo (triangles) strains carrying a spo0A (PS)-bgaB (A) or spoVG-bgaB (B) fusion were grown at 37°C in 2× SG medium containing 0.1% glucose in the absence (open symbols) and presence (solid symbols) of 30 mM NaCl. Samples were taken at the indicated time to determine the extent of growth and to measure β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and Methods.

The effect of the sof-1 mutation on the shaA mutant.

Spo0A-P is generated through an active phosphorelay system, and it induces the transcription of the components of the system, spo0F as well as spo0A itself, from their ςH-dependent PS promoters at the time of the onset of sporulation (47, 48). This allows the stimulation of the phosphorelay in a positive feedback manner and then an increase in the level of Spo0A-P at an early stage of sporulation (48). Since the addition of 30 mM NaCl severely blocked the induction of spo0A (PS) expression in the shaA mutant, it may be that the phosphorelay becomes stagnant under these conditions because of an insufficient supply of Spo0A protein. If disruption of shaA affects Spo0A-P production by inhibiting the phosphorelay, it is expected that spo0A (PS)-bgaB expression would be restored when Spo0A is phosphorylated independent of the phosphorelay. We therefore introduced the sof-1 mutation (24, 28), which is a mutation within the spo0A locus and which serves to bypass the need for spo0F in the phosphorylation of Spo0A, into the shaA mutant and examined whether spo0A (PS) induction was restored or not in the presence or absence of 30 mM NaCl.

As shown in Fig. 4, the rate of spo0A (PS) induction in the shaA sof-1 double mutant was lower than that in the wild type in the absence of added NaCl, and the induction was blocked by the addition of 30 mM NaCl. Moreover, sporulation of the shaA sof-1 double mutant occurred with the same yield of spores produced as that in the case of the shaA mutant (∼105 to 107 spores per ml in 2× SG medium and less than 10 spores per ml in 2× SG medium with 30 mM NaCl at T22).

FIG. 4.

Effect of the sof-1 mutation on spo0A (PS) transcription in a shaA::neo strain. Cells carrying a spo0A (PS)-bgaB fusion were grown at 37°C in 2× SG medium containing 0.1% glucose in the absence (open symbols) and presence (solid symbols) of 30 mM NaCl. Circles, RIK62 (sof-1 spo0FΔS shaA+); triangles, SK662 (sof-1 spo0FΔS shaA::neo).

A posttranscriptional regulation of ςH is affected in the shaA mutant.

The finding that the sof-1 mutation failed to restore spo0A (PS) induction in the shaA mutant suggested that the defect in spo0A (PS) expression in the shaA mutant may involve the loss of ςH function. We therefore examined the expression of another ςH-dependent gene, spoVG, in the shaA mutant. As shown in Fig. 3B, induction of spoVG expression was severely inhibited by the addition of 30 mM NaCl, as in the case of spo0A (PS) expression. These results clearly showed that disruption of shaA resulted in Na+ sensitivity of ςH-dependent transcription during sporulation.

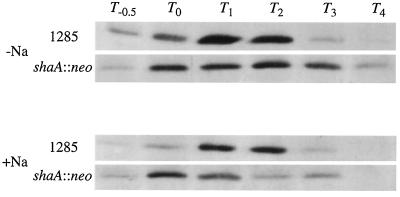

It is expected that the defects in ςH-dependent transcription are the result of a decrease in the intracellular level of ςH protein and/or a decrease in E-ςH transcription activity. We therefore assayed the level of ςH protein in extracts of cells grown in 2× SG medium in the presence or absence of 30 mM NaCl by Western blot analysis with anti-ςH antibody. As shown in Fig. 5, the level of ςH in the wild-type cells began to increase at T0, reached a maximum at T2, and then rapidly decreased after T3, which was in good agreement with results reported previously (38, 40). On the other hand, the level of ςH in the shaA mutant increased from T0 through T2 and began to decrease at T3 in the absence of added NaCl. The ςH level at T1 and T2 was slightly lower than that of the wild type, which may explain the lower rate of induction of the ςH-dependent genes. In the presence of 30 mM NaCl, ςH accumulated at T0, but the level of ςH decreased after T1 in the shaA mutant. The addition of NaCl did not affect ςH accumulation in the wild type. Thus, we concluded that the defects in ςH-dependent transcription in the shaA mutant are the result of impaired accumulation of ςH protein at an early stage of sporulation.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of ςH protein from whole-cell extracts of UOT1285 (shaA+) and SK6 (shaA::neo) cells. Cells were grown at 37°C in 2× SG medium containing 0.1% glucose with or without 30 mM NaCl and harvested at the time indicated. Aliquots of cell lysates (15 μg of total protein) were electrophoresed and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods.

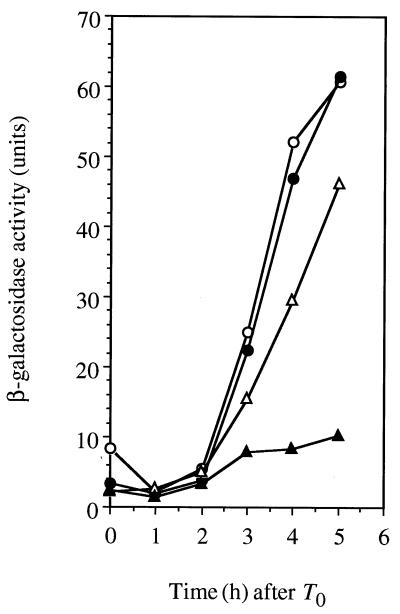

It has been shown that the intracellular level of ςH protein increases at the onset of sporulation through both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms, and then the ςH-dependent genes are induced (2, 19, 54). Since the addition of NaCl inhibited the accumulation of ςH in the shaA mutant, we next determined the level of expression of spo0H, which encodes ςH. Its promoter is recognized by E-ςA and is repressed by AbrB during the vegetative phase (54). As shown in Fig. 6, in the absence of added NaCl, the induction of spo0H in the shaA mutant showed normal timing and the level of expression of spo0H was somewhat higher than that in the wild type. In the presence of 30 mM NaCl, the spo0H expression level in the shaA mutant was lower than that in the absence of NaCl, but it was not significantly lower compared with that in the wild type. In particular, the induction rates from T0 through T2 were almost the same for the shaA mutant and the wild type. These results indicated that the decrease in the ςH level in the shaA mutant that occurred with the addition of NaCl was not due to a decrease in spo0H transcription. These results suggested that posttranscriptional regulation of ςH was mainly affected in the shaA mutant by the addition of 30 mM NaCl.

FIG. 6.

Expression of a spo0H-bgaB transcriptional fusion in shaA+ (RIK50 [circles]) and shaA::neo (SK650 [triangles]) strains. Cells were grown at 37°C in 2× SG medium containing 0.1% glucose in the absence (open symbols) and presence (solid symbols) of 30 mM NaCl.

DISCUSSION

We showed here that disruption of the Na+/H+ antiporter, ShaA, results in a Na+-sensitive sporulation-deficient phenotype. It is not the growth defect in the shaA mutant that causes the sporulation defect. Since ShaA is the major Na+ extrusion mechanism in B. subtilis (31), the shaA-disrupted mutant is considered to have a diminished ability to maintain a low internal sodium concentration. The defect in sporulation resulting from the disruption of shaA is, therefore, considered to be due to inhibition of some steps in the sporulation process by an increased level of internal Na+. Furthermore, such steps sensitive to Na+ seem to be limited at early stages (before T3).

To understand which step or steps in sporulation are affected by Na+, we examined the expression of early sporulation genes in the shaA mutant. We found that the ςH-dependent expression of both spo0A (PS) and spoVG was severely affected in the shaA mutant by the addition of 30 mM NaCl. At the same time, the level of ςH protein was diminished in the mutant cells. The accumulation of ςH protein was already observed at T0 in SK6 cells, in the presence or absence of 30 mM NaCl. Asai et al. (2) found a similar effect on ςH accumulation when glucose and glutamine were in excess. Introduction of the sof-1 mutation into the shaA mutant to bypass the phosphorelay did not restore spo0A (Ps) expression, suggesting that the primary defect in sporulation conferred by the shaA::neo mutation is not directly related to phosphorylation of Spo0A.

It is likely that ςA-dependent transcription is not affected by the shaA mutation, as shown by the absence of any defect in the vegetative growth. The fact that spo0H transcription, which depends on ςA, was not affected in the shaA mutant shows that the shaA mutation affects some steps in ςH control subsequent to spo0H transcription. The expression of spo0H is repressed by the repressor AbrB during the vegetative phase of growth and is induced at the onset of sporulation by repression of abrB transcription by Spo0A-P (54). Since less Spo0A-P is needed for the repression of abrB than for the activation of spo0A (PS) or stage II genes (8, 37, 50), it is likely that a small amount of Spo0A-P, but enough to allow spo0H expression through the AbrB pathway, would be produced in the shaA mutant.

The existence of a posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism(s) governing the level of ςH has been clearly demonstrated (9, 15, 19), but the detailed features of the mechanism remain to be elucidated. Liu et al. (35) have recently reported that ςH is subject to additional levels of posttranslational control involving the ATP-dependent protease Lon and the regulatory ATPase ClpX. Ohashi et al. (40) have recently isolated spo0H(Ts) mutants in which the level of ςH is decreased at the nonpermissive temperature. Based on the finding that mutations within rpoB encoding the β subunit of RNA polymerase restore the level of ςH in these temperature-sensitive mutants, they suggest that holoenzyme formation contributes to the stabilization of ςH at the start of sporulation (40). Our observation that an increased level of internal Na+ may affect posttranscriptional regulation of ςH leads us to speculate that a reaction(s) or interaction(s) sensitive to Na+ may be involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of ςH. It seems that ςH is unable to stably associate with RNA polymerase to form the holoenzyme under conditions in which the internal Na+ concentration is high. Alternatively, the impaired accumulation of ςH in the shaA mutant may be the consequence of abnormal induction of the Lon- or ClpX-dependent proteolytic regulation of ςH under conditions in which the internal Na+ concentration is high.

There is another report that offers an important suggestion concerning posttranscriptional control of the ςH protein. Cosby and Zuber (9) showed that an increase in the pH of the culture medium from ∼5 to 7 results in an increase in the level of expression of ςH-dependent genes and, thus, an increase in the level of ςH protein, whereas spo0H transcription is not fully increased, under conditions in which glucose and glutamine are present in excess. An active tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle seems to be required for the induction of ςH-dependent gene expression caused by elevation of the pH (9). It is unknown, however, how elevation of the external pH causes an increase in the internal ςH level. We think that the increase in pH itself rather than the absolute value of external pH may be important in stabilization of ςH based on the following considerations. Cytoplasmic pH is not maintained entirely constant, but it changes far less than the external pH; that is, there is substantial pH homeostasis (3, 32, 43). Since the magnitude of the proton motive force (Δp) is relatively independent of external pH, the composition of Δp (the chemical component ΔpH versus the electrical component ΔΨ) has to change in response to external pH to provide such pH homeostasis (43). Under acidic conditions, a large inwardly directed ΔpH mainly contributes to Δp (30). Thus, it is likely that transient elevation of the external pH under the above conditions would result in a decrease in ΔpH, and, therefore, Δp. As a consequence, the TCA cycle and respiration would be activated in order to support recovery of the Δp. The improved Δp would activate several secondary membrane transporters, including Na+/H+ antiporters, and thereby change internal ion levels, which would be expected to result in the stabilization of ςH. Thus, the results reported by Cosby and Zuber (9) indicating that an increase in external pH results in stabilization of ςH and our results indicating that disruption of shaA leads to an increased level of internal Na+ which affects the accumulation of ςH may raise the possibility that posttranscriptional regulation of ςH is influenced by internal ion levels, including the internal pH and/or the internal Na+ concentration.

Many studies on bacterial Na+/H+ antiporters have focused on pH homeostasis or sodium extrusion during vegetative growth. We have shown here that the function of the ShaA antiporter is required for the initiation of sporulation. Considering that a subtle change in internal pH and/or ion concentrations can alter cellular reactions or interactions, fine control of cytoplasmic ion levels is likely to be very important for cellular functions that involve many complicated reactions and steps, such as sporulation.

It has been shown recently that shaA and the six genes adjacent to it are transcribed as an operon (25). According to our preliminary findings in primer extension analyses, three bands of reverse transcripts were detected, suggesting that there are three transcriptional start sites in the regulatory region of the sha operon (unpublished results). In the region upstream of each start site, two apparent ςA-dependent promoters and a ςB-like promoter were found. However, the primer-extended band corresponding to the ςB-like promoter did not disappear in the case of a sigB-null mutant, suggesting that expression of the sha operon may depend on other sigma factors, such as the extracytoplasmic function-type sigma factors (36). The regulatory mechanism controlling transcription of the sha operon during both vegetative growth and sporulation is the subject of future study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Roy H. Doi for critical reading of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Abraham L. Sonenshein for helpful suggestions.

This work was partially supported by a grant for the Biodesign Research Program from RIKEN to S.K., M.K., and T.K. and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan to F.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asai K, Fujita M, Kawamura F, Takahashi H, Kobayashi Y, Sadaie Y. Restricted transcription from sigma H or phosphorylated Spo0A dependent promoters in the temperature-sensitive secA341 mutant of Bacillus subtilis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1707–1713. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai K, Kawamura F, Yoshikawa H, Takahashi H. Expression of kinA and accumulation of ςH at the onset of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6679–6683. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6679-6683.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Booth I R. Regulation of cytoplasmic pH in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:359–378. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.4.359-378.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burbulys D, Trach K A, Hoch J A. The initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by a multicomponent phosphorelay. Cell. 1991;64:545–552. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90238-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charney J, Fisher W P, Hegarty C P. Manganese as an essential element for sporulation in the genus Bacillus. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:145–148. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.2.145-148.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng J, Guffanti A A, Krulwich T A. The chromosomal tetracycline resistance locus of Bacillus subtilis encodes a Na+/H+ antiporter that is physiologically important at elevated pH. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27365–27371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chibazakura T, Kawamura F, Takahashi H. Differential regulation of spo0A transcription in Bacillus subtilis: glucose represses promoter switching at the initiation of sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2625–2632. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2625-2632.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung J D, Stephanopoulos G, Ireton K, Grossman A D. Gene expression in single cells of Bacillus subtilis: evidence that a threshold mechanism controls the initiation of sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1977–1984. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1977-1984.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosby W M, Zuber P. Regulation of Bacillus subtilis ςH (Spo0H) and AbrB in response to changes in external pH. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6778–6787. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6778-6787.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubnau D, Davidoff-Abelson R. Fate of transforming DNA following uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis. I. Formation and properties of the donor-recipient complex. J Mol Biol. 1971;14:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan L, Alper S, Arigoni F, Losick R, Stragier P. Activation of cell-specific transcription by a serine phosphatase at the site of asymmetric division. Science. 1995;270:641–644. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher S H, Sonenshein A L. Control of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortnagel P, Freese E. Inhibition of aconitase by chelation of transition metals causing inhibition of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:5289–5295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freese E B, Vasantha N, Freese E. Identification in developmental mutants of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;170:67–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00268581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisby D, Zuber P. Mutations in pts cause catabolite-resistant sporulation and altered regulation of spo0H in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2587–2595. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2587-2595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimshaw C E, Huang S, Hanstein C G, Strauch M A, Burbulys D, Wang L, Hoch J A, Whiteley J M. Synergistic kinetic interactions between components of the phosphorelay controlling sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1365–1375. doi: 10.1021/bi971917m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grinstein S, Woodside M, Sardet C, Pouyssegur J, Rotin D. Activation of the Na+/H+ antiporter during cell volume regulation. Evidence for a phosphorylation-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23823–23828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamamoto T, Hashimoto M, Hino M, Kitada M, Seto Y, Kudo T, Horikoshi K. Characterization of a gene responsible for the Na+/H+ antiporter system of alkaliphilic Bacillus species strain C-125. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:939–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healy J, Weir J, Smith I, Losick R. Post-transcriptional control of a sporulation regulatory gene encoding factor ςH in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:477–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiramatsu T, Kodama K, Kuroda T, Mizushima T, Tsuchiya T. A putative multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6642–6648. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6642-6648.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirata H, Fukazawa T, Negoro S, Okada H. Structure of a β-galactosidase gene of Bacillus stearothermophilus. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:722–727. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.722-727.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirata H, Negoro S, Okada H. High production of thermostable β-galactosidase of Bacillus stearothermophilus in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1547–1549. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.6.1547-1549.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoch J A. Regulation of the phosphorelay and the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:441–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoch J A, Trach K, Kawamura F, Saito H. Identification of the transcriptional suppressor sof-1 as an alteration in the spo0A protein. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:552–555. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.552-555.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito M, Guffanti A A, Oudega B, Krulwich T A. mrp, a multigene, multifunctional locus in Bacillus subtilis with roles in resistance to cholate and to Na+ and in pH homeostasis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2394–2402. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2394-2402.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivey D M, Guffanti A A, Bossewitch J S, Padan E, Krulwich T A. Molecular cloning and sequencing of a gene from alkaliphilic Bacillus firmus OF4 that functionally complements an Escherichia coli strain carrying a deletion in the nhaA Na+/H+ antiporter gene. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23483–23489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivey D M, Guffanti A A, Zemsky J, Pinner E, Karpel R, Schuldiner S, Padan E, Krulwich T A. Cloning and characterization of a putative Ca2+/H+ antiporter gene from Escherichia coli upon functional complementation of Na+/H+ antiporter-deficient strains by the overexpressed gene. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11296–11303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawamura F, Saito H. Isolation and mapping of a new suppressor mutation of an early sporulation gene spo0F mutation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;192:330–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00392171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawano M, Igarashi K, Kakinuma Y. The Na+-responsive ntp operon is indispensable for homeostasis of K+ and Na+ in Enterococcus hirae at limited proton potential. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4942–4945. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4942-4945.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan S, Macnab R M. Proton chemical potential, proton electrical potential and bacterial motility. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:599–614. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(80)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosono S, Morotomi S, Kitada M, Kudo T. Analyses of a Bacillus subtilis homologue of the Na+/H+ antiporter gene which is important for pH homeostasis of alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. C-125. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1409:171–175. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krulwich T A, Cheng J, Guffanti A A. The role of monovalent cation/proton antiporters in Na+-resistance and pH homeostasis in Bacillus: an alkaliphile versus a neutralophile. J Exp Biol. 1994;196:457–470. doi: 10.1242/jeb.196.1.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanyi J K. The role of Na+ in transport processes of bacterial membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;559:377–397. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(79)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leighton T J, Doi R H. The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:3189–3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Cosby W M, Zuber P. Role of Lon and ClpX in the post-translational regulation of a sigma subunit of RNA polymerase required for cellular differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:415–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Missiakas D, Raina S. The cytoplasmic function sigma factors: role and regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1059–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mueller J P, Sonenshein A L. Role of the Bacillus subtilis gsiA gene in regulation of early sporulation gene expression. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4374–4383. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4374-4383.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nanamiya H, Ohashi Y, Asai K, Moriya S, Ogasawara N, Fujita M, Sadaie Y, Kawamura F. ClpC regulates the fate of a sporulation initiation sigma factor, ςH protein, in Bacillus subtilis at elevated temperatures. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:505–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nozaki K, Kuroda T, Mizushima T, Tsuchiya T. A new Na+/H+ antiporter, NhaD, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1369:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohashi Y, Sugimaru K, Nanamiya H, Sebata T, Asai K, Yoshikawa H, Kawamura F. Thermo-labile stability of ςH (Spo0H) in temperature-sensitive spo0H mutants of Bacillus subtilis can be suppressed by mutations in RNA polymerase β subunit. Gene. 1999;229:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padan E, Maisler N, Taglicht D, Karpel R, Schuldiner S. Deletion of ant in Escherichia coli reveals its function in adaptation to high salinity and an alternative Na+/H+ antiporter system(s) J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20297–20302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Padan E, Schuldiner S. Molecular physiology of Na+/H+ antiporters, key transporters in circulation of Na+ and H+ in cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1185:129–151. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padan E, Zilberstein D, Schuldiner S. pH homeostasis in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;650:151–166. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(81)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinner E, Padan E, Schuldiner S. Kinetic properties of NhaB, a Na+/H+ antiporter from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26274–26279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Putnoky P, Kereszt A, Nakamura T, Endre G, Grosskopf E, Kiss P, Kondorosi A. The pha gene cluster of Rhizobium meliloti involved in pH adaptation and symbiosis encodes a novel type of K+ efflux system. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1091–1101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scribner H E, Mogelson J, Eisenstadt E, Silver S. Regulation of cation transport during bacterial sporulation. In: Gerhardt P, Costilow R N, Sadoff H L, editors. Spores VI. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1975. pp. 346–355. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strauch M A, Trach K A, Day J, Hoch J A. Spo0A activates and represses its own synthesis by binding at its dual promoters. Biochimie. 1992;74:619–626. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strauch M A, Wu J J, Jonas R H, Hoch J A. A positive feedback loop controls transcription of the spo0F gene, a component of the sporulation phosphorelay in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:967–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taglicht D, Padan E, Schuldiner S. Overproduction and purification of a functional Na+/H+ antiporter coded by nhaA (ant) from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11289–11294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trach K A, Hoch J A. Multisensory activation of the phosphorelay initiating sporulation in Bacillus subtilis: identification and sequence of the protein kinase of the alternate pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tzeng Y-L, Feher V A, Cavanagh J, Perego M, Hoch J A. Characterization of interactions between a two-component response regulator, Spo0F, and its phosphatase, RapB. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16538–16545. doi: 10.1021/bi981340o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Utsugi J, Inaba K, Kuroda T, Tsuda M, Tsuchiya T. Cloning and sequencing of a novel Na+/H+ antiporter gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1398:330–334. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waser M, Hess-Bienz D, Davies K, Solioz M. Cloning and disruption of a putative Na+/H+ antiporter gene of Enterococcus hirae. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5396–5400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weir J, Predich M, Dubnau E, Nair G, Smith I. Regulation of spo0H, a gene coding for the Bacillus subtilis ςH factor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:521–529. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.521-529.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.West I C, Mitchell P. Proton/sodium ion transport in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1974;144:87–90. doi: 10.1042/bj1440087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]