Towards the end of 2021, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine effectiveness was threatened by the emergence of the omicron clade (B.1.1.529), with more than 30 mutations in the spike protein. Recently, several sublineages of omicron, including BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5, have shown even greater immune evasion,1, 2, 3, 4 and are driving waves of infections worldwide.

One emerging sublineage, BA.2.75, is increasing in frequency in India and had been detected in at least 15 countries as of July 19, 2022. Relative to BA.2, BA.2.75 carries nine additional mutations in the spike protein (appendix p 2): K147E, W152R, F157L, I210V, G257S, G339H, G446S, N460K, and a reversion towards the ancestral variant, R493Q. G446S has been predicted to be a site of potential escape from antibodies elicited by current vaccines that still neutralise omicron.5 Furthermore, it has been identified as a site of potential escape from LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab), which represents one of the last remaining classes of first-generation monoclonal antibodies that can cross-neutralise BA.2, BA.4, and BA.5.1 As waves of omicron infections have occurred in many countries, identifying the sensitivity of newly emerging variants to neutralisation by sera sampled subsequent to these waves is required to inform public health policy.

Here we report the sensitivity of the BA.2.75 spike protein to neutralisation by a panel of clinically relevant and preclinical monoclonal antibodies, as well as by serum from blood donated in Stockholm, Sweden, during Nov 8–14, 2021 (n=20), and April 11–17, 2022 (n=20). These periods coincide with points before and after a large wave of infections dominated by BA.1 and BA.2 (December, 2021, to February, 2022), as well as an expansion of vaccine booster doses (appendix p 3).

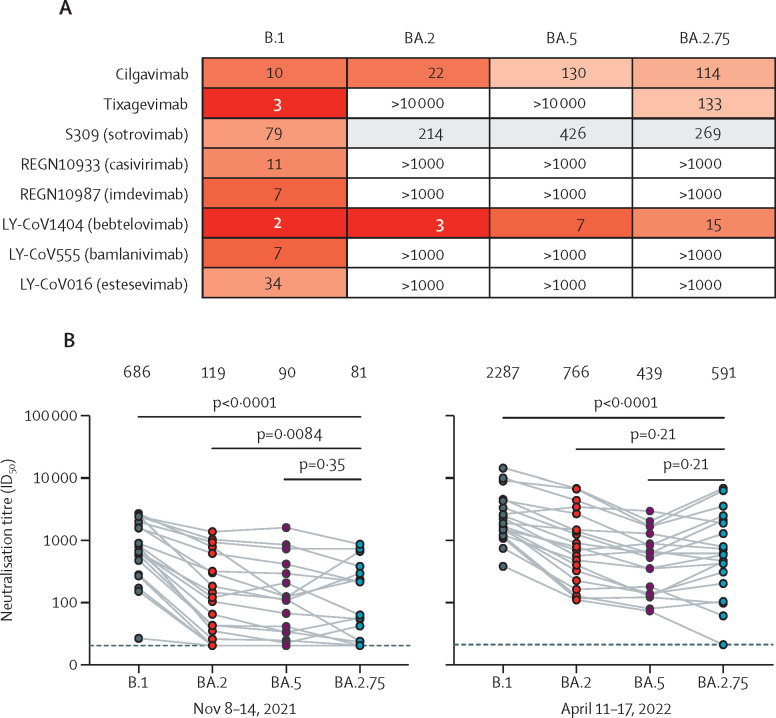

Cilgavimab had approximately 11-fold reduced potency against BA.2.75 compared with the ancestral B.1 (D614G), in line with its potency against BA.5 (figure A ; appendix pp 4–5). Although only capable of extremely weak neutralisation of BA.2, tixagevimab showed partially restored activity against BA.2.75, possibly due, in part, to the reversion to the ancestral amino acid at spike position 493. Although bebtelovimab showed reduced potency against BA.2.75, probably due to G446S, the reduction was only around 7-fold, and bebtelovimab still potently neutralised BA.2.75. Casivirimab, imdevimab, bamlanivimab, and etesevimab did not neutralise BA.2.75. The relative sensitivity of BA.2.75 observed here is largely concordant with data from two other studies,6, 7 although the magnitude of the loss of potency for cilgavimab shows substantial variation between the three studies.

Figure.

Evasion of neutralising antibodies by BA.2.75

(A) Neutralising 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) titres (ng/μl) for monoclonal antibodies against ancestral B.1 (D614G) and omicron sublineages BA.2, BA.5, and BA.2.75 in a pseudovirus neutralisation assay. (B) Neutralisation of BA.2.75 relative to BA.2, BA.5, and B.1 by serum (n=20) from blood donated Nov 8–14, 2021, in Stockholm, Sweden, before a wave of infections dominated by BA.1 and BA.2 (left-hand chart). Neutralisation by serum (n=20) donated April 11–17, 2022, after the infection wave (right-hand chart). Values shown above the charts in (B) are the geometric mean ID50 titres. Serum with an ID50 less than the lowest dilution tested (20, dotted line) is plotted as 20. ID50=50% inhibitory dilution.

BA.2.75 was neutralised with the lowest geometric mean ID50 titre of all variants evaluated by serum sampled before the BA.1 and BA.2 infection wave (Nov 8–14, 2022; figure B), with titres to BA.2.75 approximately 8-times lower compared with ancestral B.1 (D614G). For sera sampled before the infection wave, titres against BA.2.75 were slightly but significantly lower than those against BA.2, and similar to those against BA.5. Sera sampled following the BA.1 and BA.2 infection wave showed substantially increased neutralisation against ancestral B.1, as well as enhanced cross-neutralisation of omicron sublineages. Geometric mean titres against BA.2.75 after the BA.1 and BA.2 infection wave were more than 7 times those of sera sampled before the wave of infections (appendix p 6), probably reflecting a combined contribution of BA.1 and BA.2 infections, as well as third-dose booster vaccine rollout, with coverage in Stockholm expanding among people aged 18 years or older from 5% during Nov 8–14, 2021, to 59% during April 11–17, 2022 (appendix p 3). During April 11–17, 2022, titres against BA.2.75 were slightly but significantly lower than those against BA.2, and similar to those against BA.5. The relative sensitivity of BA.2.75 in these cohorts of blood donors is largely concordant with those seen in vaccinated individuals (CoronaVac; Sinovac Life Sciences, Beijing, China) with and without BA.1 or BA.2 breakthrough infection.7

As infection histories become more complex, and a large proportion of infections go undetected, monitoring of population-level immunity from random samples is increasingly crucial for understanding and contextualising the immune evasion properties of new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Here we show that the emerging sublineage, BA.2.75, does not show greater antibody evasion than the currently dominating BA.5 variant in a set of random samples from Stockholm. BA.2.75 largely maintains sensitivity to bebtelovimab despite a slight reduction in potency, and exhibits moderate susceptibility to tixagevimab and cilgavimab.

STR is a cofounder of, and held shares in, deepCDR Biologics, which has been acquired by Alloy Therapeutics. DJS, GBKH, and BM have intellectual property rights associated with antibodies that neutralise omicron variants. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Cao Y, Yisimayi A, Jian F, et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by omicron infection. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/S41586-022-04980-y. published online June 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu P, Faraone J, Evans JP, et al. Neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.4/5 and BA.2.12.1 subvariants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2526–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2206725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora P, Kempf A, Nehlmeier I, et al. Augmented neutralisation resistance of emerging omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1117–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00422-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamasoba D, Kosugi Y, Kimura I, et al. Neutralisation sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:942–943. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00365-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greaney AJ, Starr TN, Bloom JD. An antibody-escape estimator for mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain. Virus Evol. 2022;8 doi: 10.1093/ve/veac021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamasoba D, Kimura I, Kosugi Y, et al. Neutralization sensitivity of omicron BA.2.75 to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.07.14.500041. published online July 15. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y, Yu Y, Song W, et al. Neutralizing antibody evasion and receptor binding features of SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.2.75. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.07.18.500332. published online July 19. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.