Abstract

Major pathological response (MPR) is a potential surrogate for overall survival. We determined whether the dynamic changes in 18F‐labeled fluoro‐2‐deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F‐FDG PET/CT) were associated with MPR in patients receiving neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Forty‐four patients with stage II–III non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who received neoadjuvant immunotherapy and radical surgery were enrolled. Moreover, 18F‐FDG PET/CT scans were performed at baseline and within 1 week before surgery to evaluate the disease. All histological sections were reviewed to assess MPR. The detailed clinical features of the patients were analyzed. The reliability of the clinical variables was assessed in differentiating between MPR and non‐MPR using logistic regression. Receiver‐operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis identified the SUVmax changes threshold most associated with MPR. Most of the patients were pathologically diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma and received anti‐PD‐1 antibodies plus chemotherapy. The immunotherapy regimens included nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and camrelizumab. MPR was observed in more than half of lesions. Tumors with MPR had a higher decrease in the longest dimension on dynamic PET/CT than those without MPR. Furthermore, the decline in SUVmax was significantly different between MPR and non‐MPR diseases, and MPR lesions had a prominent mean reduction in SUVmax. SUVmax reduction was independently associated with MPR in the multivariate regression. On ROC analysis, the threshold of SUVmax decrease in 60% was associated with MPR. Dynamic changes in SUVmax were associated with MPR. The tumors with MPR showed a greater PET/CT response than those without MPR. A SUVmax decrease of more than 60% is more likely to result in an MPR after receiving neoadjuvant immunotherapy.

Keywords: 18F‐FDG PET/CT, immunotherapy, major pathological response, neoadjuvant therapy, non‐small cell lung cancer

It is not clear whether the features of 18F‐FDG PET/CT between the patients with MPR and without MPR who receive preoperative immunotherapy are different. In this study, we found that the decline of SUVmax in dynamic 18F‐FDG PET/CT were significantly different between MPR and non‐MPR groups. A SUVmax decrease of more than 60% is more likely to result in an MPR. Dynamic 18F‐FDG PET/CT was important to evaluate the clinical response of preoperative immunotherapy and determined the potential beneficial population from neoadjuvant immunotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Stage II–III non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has high heterogeneity, involves multidisciplinary and different therapy regimens, and shows distinct prognoses. Patients with stage II–III disease still have a high risk of recurrence, even if they undergo radical surgery. 1 Preoperative chemotherapy is recommended for patients with resectable NSCLC, but it has limited survival benefits. 1 , 2 , 3 Although data with a longer follow‐up duration are not mature, immunotherapy as a neoadjuvant treatment shows encouraging efficacy. 4 , 5 , 6 Major pathological response (MPR) has been used in several randomized clinical trials as an exploratory endpoint and is expected to be associated with survival. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

18F‐labeled fluoro‐2‐deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F‐FDG PET/CT) is a helpful tool that can reflect the tumor size and glycometabolism in the whole body and is widely used in evaluating tumor stages and therapeutic responses. It is important to determine patients who have a great response to immunotherapy because incorrect evaluation judgment may lead to making incorrect decisions about the next step of treatment after induced immunotherapy. In particular, discordance occurred between the CT Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors and the histopathological response. 9 Progression or stable CT at a single time does not mean that the disease has a poor response to immunotherapy or has no potential opportunity to receive surgery. Some researchers have suggested that 18F‐FDG PET/CT may be more accurate in predicting pathological responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. 10 , 11 Nivolumab, 12 pembrolizumab, 13 and camrelizumab 14 have shown great effect in locally advanced NSCLC. In this real‐world retrospective study, we performed analyses to determine whether the dynamic changes in 18F‐FDG PET/CT were associated with MPR in patients receiving different preoperative immunotherapies.

METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively enrolled patients with stage II–III (eighth edition) NSCLC at baseline who had received preoperative immune checkpoint inhibitors treatment and underwent surgery at Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital between July 2019 and July 2021. 18F‐FDG PET/CT scans were performed at baseline and within 1 week before surgery. All primary tumors and lymph nodes were subjected to standard MPR evaluation by two pathologists. Detailed clinicopathological characteristics were collected for analysis. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the hospital (GDREC2016175H[R2]). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Major pathological response assessments

All histological sections were reviewed by two pathologists following the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Multidisciplinary Recommendations for Pathologic Assessment of Lung Cancer Resection Specimens After Neoadjuvant Therapy. 15 The primary components of the tumor bed, including viable tumor, necrosis, and stroma were described and recorded. MPR is defined as ≤10% of the viable tumor.

18 F ‐labeled fluoro‐2‐deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans

18F‐FDG PET/CT scans were performed using Siemens Biograph16 when treatment‐naïve and within 1 week before surgery. Before the scan, all patients needed to fast for more than 4–6 h and were required to have blood glucose levels less than 7.0 mmol/l. The dose of 18F‐FDG was 0.16 mCi/Kg. PET/CT images were obtained in 60–70 min after 18F‐FDG injection. From head to thigh, the scan speeds were 5 min/bed (head, 1 bed) and 2 min/bed (skull base to thigh, 5–8 beds). Noncontrast CT was used to adjust the attenuation with a tube voltage of 120 kV and a tube current of 50 mAs. The tube voltage of the spiral contrast‐enhanced CT was 120 kV, and the tube currents were 300 mAs (head), 140 mAs (chest), and 180 mAs (abdomen). The images were independently assessed and evaluated by two nuclear medicine specialists.

Statistical analysis

Consecutive data are presented as median ± standard deviation or interquartile range (IQR). Student's t‐tests were used to compare differences in the parameter variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using the correction for continuity x 2 test, Pearson x 2 test, or Fisher's precision test. Logistic regression was performed to determine the independent association between clinical variables and MPR. Subsequently, the sensitivity and specificity were explored via receiver‐operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine the dynamic SUVmax changes threshold that could best separate MPR from non‐MPR. All statistical analyses were performed using the International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp.). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 44 patients were finally enrolled in this study (Table 1). Most were male (37/44, 84.1%) and smokers (30/44, 68.2%), and mean age was 59.2 (IQR, 53–67) years. Almost two‐thirds of the tumors (28/44, 63.6%) showed MPR (Figure 1), and the rest were non‐MPR (16/44, 36.4%) (Figure 2) Hematoxylin and eosin staining examples are shown in Figure 3. The majority of the pathological diagnoses were squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, 27/44, 61.4%), followed by adenocarcinoma (9/44, 20.5%), and lymphoepithelioma‐like carcinoma (8/44, 18.2%). Almost 80% of the patients (35/44, 79.6%) had stage III NSCLC (eighth edition) at baseline, and most of them finally received three cycles of immunotherapy plus chemotherapy (41/44, 93.2%). Approximately 60% of the patients received nivolumab (29/44, 65.9%), 18% received pembrolumab (8/44, 18.2%), and 16% received camrelizumab (7/44, 15.9%) as immunotherapy regimens. Paclitaxel (albumin‐bound) and platinum (36/44, 81.8%) were the dominant chemotherapy regimens. There were no significant differences between tumors with MPR and without MPR in terms of age, sex, smoking history, pathological diagnosis, tumor‐node‐metastasis (TNM) stages, programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1), neoadjuvant, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy regimens (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of the cohort

| Patient characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 44 (100%) | ||

| Age, years, mean (IQR) | 59.2 (53–67) | |

| Sex (n,%) | ||

| Female | 7 (15.9%) | |

| Male | 37 (84.1%) | |

| Smoker | ||

| Yes | 30 (68.2%) | |

| No | 14 (31.8%) | |

| Pathological diagnosis | ||

| LUAD | 9 (20.4%) | |

| SCC | 27 (61.4%) | |

| LELC | 8 (18.2%) | |

| TNM stage (eighth) | ||

| II | 9 (20.5%) | |

| III | 35 (79.6%) | |

| PD‐L1, mean (IQR) | 32% (1%–60%) | |

| Neoadjuvant regimens | ||

| Immunotherapy | 3 (6.8%) | |

| Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy | 41 (93.2%) | |

| Immunotherapy regimens | ||

| Nivolumab | 29 (65.9%) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 8 (18.2%) | |

| Camrelizumab | 7 (15.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy regimens (if applicable) | ||

| Paclitaxel + platinum | 36 (81.8%) | |

| Pemetrexed + platinum | 5 (11.4%) |

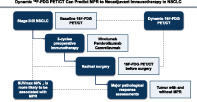

FIGURE 1.

A 41‐year‐old man was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma and received three cycles of nivolumab plus paclitaxel (albumin‐bound) and carboplatin. (a) Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans at baseline, (b) PET/CT scans within 1 week before surgery

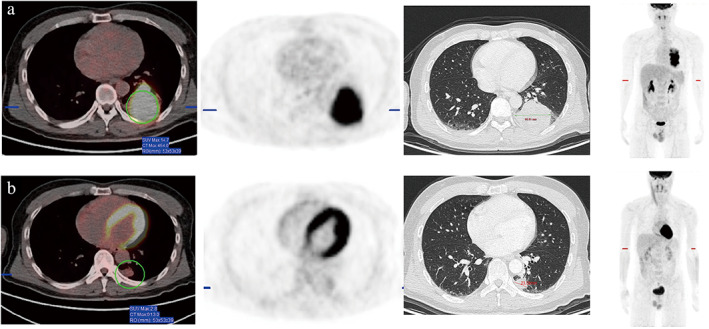

FIGURE 2.

A 48‐yearsold woman was diagnosed with lymphoepithelioma‐like carcinoma and received three cycles of pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed and carboplatin. (a) Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans at baseline, (b) PET/CT scans within 1 week before surgery

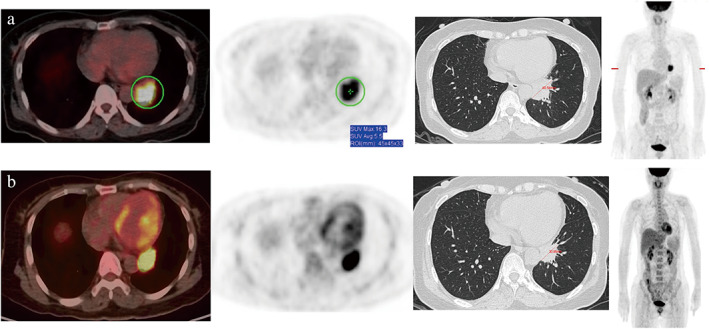

FIGURE 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed that the patient from Figure 1 had a major pathological response (MPR) and the residual viable tumor was less than 10%, and the residual viable tumor was more than 10% in the patient from Figure 2. (a) MPR with 40× and (b) 100×; (c) non‐MPR with 40× and (d) 100×

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Tumor with MPR (n = 28) | Tumor without MPR (n = 16) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (IQR) | 59.5 (53–67) | 57.9 (54–67) | 0.55 a |

| Male | 25 (89.3%) | 12 (75.0%) | 0.41 b |

| Smoker | 19 (67.9%) | 11 (68.8%) | 0.95 c |

| Pathological diagnosis | 0.06 d | ||

| LUAD | 4 (14.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | |

| SCC | 21 (75.0%) | 6 (37.5%) | |

| LELC | 3 (10.7%) | 5 (31.3%) | |

| TNM stage (eighth) | 0.55 b | ||

| II | 7 (25.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | |

| III | 21 (75.0%) | 14 (87.5%) | |

| PD‐L1, mean (IQR) | 36.3% (1%–80%) | 25.3% (5%–33%) | 0.31 a |

| Neoadjuvant regimens | 1 b | ||

| Immunotherapy | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (6.3%) | |

| Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy | 26 (92.9%) | 15 (93.8%) | |

| Immunotherapy regimens | 0.22 d | ||

| Nivolumab | 21 (75.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 4 (14.3%) | 4 (25.0%) | |

| Camrelizumab | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (25.0%) | |

| Chemotherapy regimens (if applicable) | 0.10 b | ||

| Paclitaxel e + platinum | 25 (96.2%) | 11 (73.3%) | |

| Pemetrexed + platinum | 1 (4.8%) | 4 (26.7%) |

According to a Student's t‐test.

According to a correction for the continuity x 2 test.

According to a Pearson's x 2 test.

According to a Fisher's precision test.

Paclitaxel (albumin‐bound).

Abbreviations: LELC, lymphoepithelioma‐like carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Further analyses showed that the longest dimension (p = 0.85) and SUVmax (p = 0.58) of 18F‐FDG PET/CT at baseline were not significantly different between the tumor with MPR and without MPR. SUVmax before surgery showed a significant difference (p < 0.05), whereas the longest dimension did not (p = 0.07). The dynamic longest dimension (p < 0.05) and SUVmax (p < 0.05) demonstrated significant differences between the MPR and non‐MPR groups and have a remarkable decline in two the groups (Table 3). This suggests that dynamic decreases in dimension and SUVmax value of the tumor are associated with tumor MPR.

TABLE 3.

Analyses of dynamic positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans

| Characteristics | Tumor with MPR | Tumor without MPR | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longest dimension (cm) | |||

| At baseline | 5.3 ± 3.5 | 5.1 ± 1.8 | 0.85 a |

| Before surgery | 2.7 ± 2.0 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 0.07 a |

| Changing | −45.1% ± 30.5% | −25.1% ± 22.9% | <0.05 a |

| SUVmax | |||

| At baseline | 14.8 ± 5.0 | 15.7 ± 5.2 | 0.58 a |

| Before surgery | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 8.6 ± 6.5 | <0.05 a |

| Changing | −80.4% ± 13.7% | −46.5% ± 33.0% | <0.05 a |

According to a Student's t‐test.

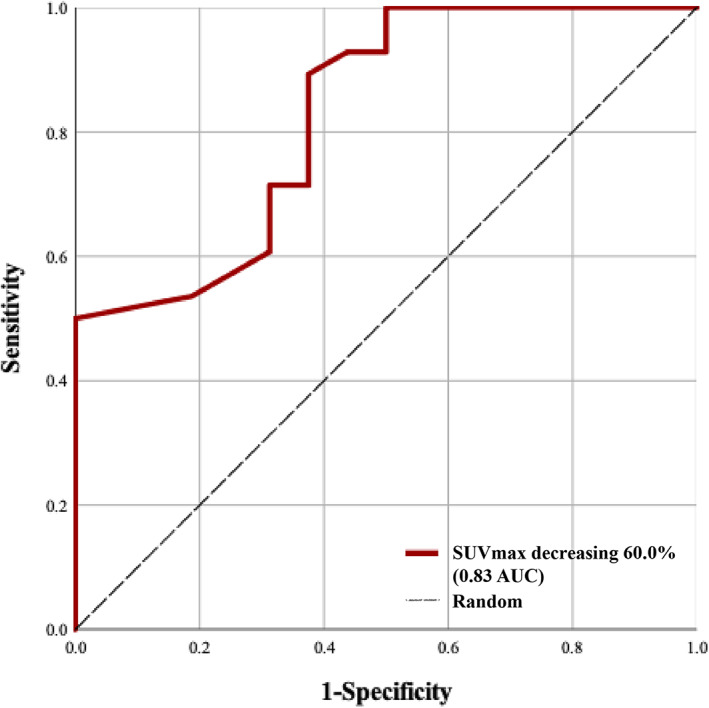

Logistic regression was used to determine the association between variables and the prediction of MPR, as opposed to non‐MPR. SUVmax reduction demonstrated an odds ratio of 386.45, with a 95% confidence interval of 4.14–36101.23 (p‐value <0.05) (Table 4). ROC analysis showed that a dynamic SUVmax decrease of 60% was the ideal threshold. SUVmax decreasing ≥60.0% was associated with MPR, with 0.83 area under the curve, 89.3% sensitivity, 62.5% specificity, 80.6% positive predictive value, and 76.9% negative predictive value (Table 5, Figure 4).

TABLE 4.

Logistic regression for major pathological response

| Variables | p‐value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD‐L1 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.01–2.05 |

| Size reduction | 0.508 | 3.13 | 0.11–91.22 |

| SUVmax reduction | 0.01 | 386.45 | 4.14–36101.23 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

TABLE 5.

Receiver‐operator characteristic (ROC) threshold and for major pathological response

| MPR (n = 28) | Without MPR (n = 16) | Total | Sensitivity % | Specificity % | PPV % | NPV % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROC threshold | SUVmax decreasing ≥60.0% | 25 | 6 | 31 | 89.3 | 62.5 | 80.6 | 76.9 |

| SUVmax decreasing <60.0% | 3 | 10 | 13 |

Abbreviations: NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

FIGURE 4.

Receiver‐operating characteristic curve of decreasing SUVmax used to differentiate major pathological response from nonmajor pathological response

DISCUSSION

Preoperative immunotherapy has demonstrated interesting short‐term outcomes in several neoadjuvant trials 4 , 5 , 6 and is expected to become a standard treatment pending long‐term efficacy releasing. MPR is considered as a vital short‐term endpoint that has the potential to replace long‐term survival outcomes in neoadjuvant immunotherapy. However, a discrepancy has been observed between the CT and pathological responses. 9 Stromal, fibrous, inflammatory, and necrotic components may confuse the assessment of radiological response in tumor size and interfere with predicting pathological response after neoadjuvant immunotherapy and before surgery. 15 Previous studies have demonstrated that modifications in metabolic activity, represented by changes in the SUV, are associated with tumor response. 16 18F‐FDG PET/CT has showed its value for predicting pathological response in patients with NSCLC who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. 10 , 11 In this study, we explored the correlation between PET/CT and MPR.

In this real‐world retrospective study, all patients with stage II–III NSCLC received three cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, radical surgery, and dynamic 18F‐FDG PET/CT scans. Surgical specimens were reviewed to assess MPR. In terms of clinical characteristics, pathological diagnosis between the patients with and without MPR showed a marginal statistical difference, and the MPR groups had a higher proportion of SCC than the non‐MPR group. In the real world, locally advanced patients with SCC are more likely to received neoadjuvant immunotherapy than those with adenocarcinoma. This was probably because SCC has lower mutation rates of targeted genes than adenocarcinoma. Perioperative targeted therapy has shown primary efficacy in patients with resectable adenocarcinoma. 17 , 18 However, it remains unclear whether patients with sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase alterations would benefit from neoadjuvant immunotherapy. These patients were excluded from some neoadjuvant immunotherapy clinical trials, such as the CheckMate‐816, 6 probably because the patients with these targeted driving mutations had risks of hyperprogression and other adverse events related to immunotherapy, 19 and had limited efficiency. 20

Response patterns of immunotherapy are different from those of targeted therapy or chemotherapy; sometimes, pseudoprogression and hyperprogression would disturb response assessment. 21 FDG PET/CT plays a vital role in evaluating the response of solid tumors to immunotherapy. One of the main reasons for this is that the SUV is a parameter that shows the tumor metabolic activity. Immune infiltrates are associated with better immunotherapy responses. A significant correlation was demonstrated between the SUV and the expression of PD‐L1 22 and CD8‐tumor‐infiltrating‐lymphocytes 23 at baseline. PD‐L1‐expressing NSCLC has a high glucose metabolism with a high SUVmax. 22 Therefore, PET/CT has the potential to reflect some characteristics of the tumor immune microenvironment and predict the response to immunotherapy. Compared with a previous study that reported that metabolic parameters calculated by PET were significantly correlated with the pathological response in patients who received two cycles of sintilimab, 24 our cohort had more diverse therapeutic regimens and evaluated MPR under IASLC multidisciplinary recommendations. In this study, there was no significant difference between the MPR and non‐MPR groups in other clinical characteristics, including TNM stage, PD‐L1 expression, and therapy regimens. Tumors with MPR showed a greater decrease in longest dimension and SUVmax. We found that SUVmax reduction in tumors on dynamic PET/CT is strongly and independently associated with MPR and provides high accuracy. In our cohort, and SUVmax decrease of more than 60% was more likely to have an MPR. These results emphasized that dynamic 18F‐FDG PET/CT is important in evaluating the clinical response of preoperative immunotherapy and can help to determine the population who can benefit from neoadjuvant immunotherapy followed by radical surgery.

This study had some limitations. First, it was retrospective with a limited small sample size. Further investigation is required to validate these results. Second, most patients received immunotherapy plus chemotherapy, with nivolumab + paclitaxel + platinum as a regimen. SCC is the most common pathological type. This may cause bias that interferes with the effectiveness of the results of this study, although it partly reflected the real‐world situation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in East Asia. Third, overall survival data were not mature; therefore, we could not determine the association between 18F‐FDG PET/CT, MPR, and prognosis.

In conclusion, dynamic changes in SUVmax on 18F‐FDG PET/CT were associated with MPR in patients who received neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Tumors with MPR showed a greater 18F‐FDG PET/CT response than those without MPR. An SUVmax decrease of more than 60% is more likely to result in an MPR after receiving preoperative immunotherapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

YLW is a consultant of AstraZeneca, Roche Holdings AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim; he has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Roche Holdings AG, Pfizer, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb; he has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Roche Holdings AG (Inst). WZZ has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Roche Holdings AG, Pfizer, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673031, 81872510), Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital Young Talent Project (GDPPHYTP201902), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (no. 2019B1515130002), High‐level Hospital Construction Project (DFJH201801, DFJH201910), Research Fund from Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (no. 201704020161), GDPH Scientific Research Funds for Leading Medical Talents and Distinguished Young Scholars in Guangdong Province (no. KJ012019449).

Chen Z‐Y, Fu R, Tan X‐Y, Yan L‐X, Tang W‐F, Qiu Z‐B, et al. Dynamic 18F‐FDG PET/CT can predict the major pathological response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in non‐small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13(17):2524–2531. 10.1111/1759-7714.14562

Zhi‐Yong Chen, Rui Fu, Xiao‐Yue Tan, and Li‐Xu Yan contributed equally to this work.

Funding information GDPH Scientific Research Funds for Leading Medical Talents and Distinguished Young Scholars in Guangdong Province, Grant/Award Number: KJ012019449; Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, Grant/Award Number: 2019B1515130002; Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital Young Talent Project, Grant/Award Number: GDPPHYTP201902; High‐level Hospital Construction Project, Grant/Award Numbers: DFJH201801, DFJH201910; National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Numbers: 81673031, 81872510; Research Fund from Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau, Grant/Award Number: 201704020161

Contributor Information

Wen‐Zhao Zhong, Email: 13609777314@163.com.

Ben‐Yuan Jiang, Email: jiangben1000@126.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J. Cisplatin‐based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(4):351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Stephens RJ, et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE collaborative group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3552–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NSCLC Meta‐analysis Collaborative Group . Preoperative chemotherapy for non‐small‐cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1561–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, Anagnostou V, Cottrell TR, Hellmann MD, et al. Neoadjuvant PD‐1 blockade in Resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378(21):1976–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shu CA, Gainor JF, Awad MM, Chiuzan C, Grigg CM, Pabani A, et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable non‐small‐cell lung cancer: an open‐label, multicentre, single‐arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):786–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M, Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, et al. Abstract CT003: Nivolumab (NIVO) + platinum‐doublet chemotherapy (chemo) vs chemo as neoadjuvant treatment (tx) for resectable (IB‐IIIA) non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the phase 3 CheckMate 816 trial. Cancer Res. 2021;81(13 Supplement):CT003. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oezkan F, He K, Owen D, Pietrzak M, Cho JH, Kitzler R, et al. OA13.07 Neoadjuvant Atezolizumab in Resectable NSCLC patients: Immunophenotyping results from the interim analysis of the multicenter trial LCMC3. Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10, Supplement):S242–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cascone T, William WN Jr, Weissferdt A, Leung CH, Lin HY, Pataer A, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in operable non‐small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 randomized NEOSTAR trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. William WN Jr, Pataer A, Kalhor N, Correa AM, Rice DC, Wistuba II, et al. Computed tomography RECIST assessment of histopathologic response and prediction of survival in patients with resectable non‐small‐cell lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(2):222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee HY, Lee HJ, Kim YT, Kang CH, Jang BG, Chung DH, et al. Value of combined interpretation of computed tomography response and positron emission tomography response for prediction of prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(4):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poettgen C, Theegarten D, Eberhardt W, Levegruen S, Gauler T, Krbek T, et al. Correlation of PET/CT findings and histopathology after neoadjuvant therapy in non‐small cell lung cancer. Oncology. 2007;73(5–6):316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M, Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus chemotherapy in Resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bar J, Urban D, Redinsky I, Ackerstein A, Daher S, Kamer I, et al. OA11.01 Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab for early stage non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(10, Supplement):S865–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu C, Chen Q, Zhou C, Wu L, Li W, Zhang H, et al. 98P Camrelizumab as neoadjuvant, first‐ or later‐line treatment for non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a retrospective real‐world study (CTONG2004). Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S1417. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Travis WD, Dacic S, Wistuba I, Sholl L, Adusumilli P, Bubendorf L, et al. IASLC multidisciplinary recommendations for pathologic assessment of lung cancer resection specimens after Neoadjuvant therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(5):709–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castello A, Rossi S, Lopci E. 18F‐FDG PET/CT in restaging and evaluation of response to therapy in lung cancer: state of the art. Curr Radiopharm. 2020;13(3):228–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhong W‐Z, Chen K‐N, Chen C, Gu C‐D, Wang J, Yang X‐N, et al. Erlotinib versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant treatment of stage IIIA‐N2 EGFR‐mutant non–small‐cell lung cancer (EMERGING‐CTONG 1103): a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(25):2235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang C, Li S‐l, Nie Q, Dong S, Shao Y, Yang X‐n, et al. Neoadjuvant crizotinib in resectable locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer with ALK rearrangement. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(4):726–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kang J, Zhang C, Zhong WZ. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for non–small cell lung cancer: state of the art. Cancer Commun. 2021;41(4):287–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee J, Chaft J, Nicholas A, Patterson A, Waqar S, Toloza E, et al. PS01. 05 surgical and clinical outcomes with Neoadjuvant Atezolizumab in Resectable stage IB–IIIB NSCLC: LCMC3 trial primary analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(3):S59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aide N, Hicks RJ, Le Tourneau C, Lheureux S, Fanti S, Lopci E. FDG PET/CT for assessing tumour response to immunotherapy: report on the EANM symposium on immune modulation and recent review of the literature. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(1):238–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takada K, Toyokawa G, Okamoto T, Baba S, Kozuma Y, Matsubara T, et al. Metabolic characteristics of programmed cell death‐ligand 1‐expressing lung cancer on (18) F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Cancer Med. 2017;6(11):2552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopci E, Toschi L, Grizzi F, Rahal D, Olivari L, Castino GF, et al. Correlation of metabolic information on FDG‐PET with tissue expression of immune markers in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who are candidates for upfront surgery. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(11):1954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tao X, Li N, Wu N, He J, Ying J, Gao S, et al. The efficiency of (18)F‐FDG PET‐CT for predicting the major pathologic response to the neoadjuvant PD‐1 blockade in resectable non‐small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47(5):1209–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]