Abstract

The structure of the viscous extracellular polysaccharide (glycan) of desiccation-tolerant Nostoc commune DRH-1 was determined through chromatographic and spectroscopic methods. The polysaccharide is novel in that it possesses a 1-4-linked xylogalactoglucan backbone with d-ribofuranose and 3-O-[(R)-1-carboxyethyl]-d-glucuronic acid (nosturonic acid) pendant groups. The presence of d-ribose and nosturonic acid as peripheral groups is unusual, and their potential roles in modulating the rheological properties of the glycan are discussed. Nosturonic acid was present in the glycans of N. commune from diverse geographic locations, suggesting that this uronic acid is an integral component of this cosmopolitan anhydrophile.

The microfossil record suggests that cyanobacteria or cyanobacteria-like prokaryotes were present on the primitive Earth in the Archaean era more than 3.5 billion years ago (28). The exquisite preservation of these microfossils is thought to reflect the intrinsic stability of the extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) and its ability to bind heavy metals as well as resist degradation (13). Extant cyanobacteria dominate the microbial populations of many extreme environments including soda lakes (Spirulina, Cyanospira), the nutrient-poor open ocean (Trichodesmium), thermal springs (Synechococcus and Mastigocladis), and the cold dry polar deserts (Chroococcidiopsis) (35). In these environments the cyanobacteria produce copious amounts of EPSs in the form of sheaths, slimes, and capsules. Very little is known about the diversity, mode of synthesis, structure, or properties of these biopolymers (19). A recent review emphasized the potential role of EPSs in the desiccation tolerance of prokaryotes (23). However, much further research is needed to resolve the specific mechanisms which biopolymers contribute to such a complex process.

The terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune has a marked capacity for desiccation tolerance and can survive storage at −400 MPa (0% relative humidity) for centuries (23). The cells produce large amounts of an unusual excreted polysaccharide that contributes in at least four ways to the marked stabilization of cells during prolonged storage in the air-dried state, at low or high temperatures. First, the glycan inhibits fusion of membrane vesicles during desiccation and freeze-drying (10) and acts as an immobilization matrix for a range of secreted enzymes which remain fully active after long-term air-dried storage (11, 27, 32). Second, the glycan provides a structural and/or molecular scaffold with rheological properties which can accommodate the rapid biophysical and physiological changes in the community upon rehydration and during recovery from desiccation. The glycan swells from brittle dried crusts to cartilaginous structures within minutes of rehydration. Third, the glycan matrix contains both lipid- and water-soluble UV radiation-absorbing pigments which protect the cell from photodegradation (12). Fourth, although epiphytes colonize the surfaces of Nostoc colonies, there is no penetration of the glycan due in part to a silicon- and calcium-rich pellicle and inherent resistance of the glycan to enzymatic breakdown. Preliminary structural work on one water-soluble UV-absorbing pigment (released from the glycan by acid hydrolysis) indicated the presence of an oligosaccharide (4), raising the possibility that the pigment may be covalently linked to the glycan in the desiccated state.

An understanding of the biochemical and biophysical properties of such biopolymers and the isolation of genes and enzymes required for their synthesis and modification can lead to an understanding of the underlying principles of extremophile stability. Furthermore, one can envision the utilization of such materials for the commercial stabilization of labile agricultural chemicals, food, pharmaceuticals, and/or biomedical materials. As part of an overall project aimed at understanding the functional genomics of extremophile biopolymers and the utilization of these materials for enhanced stability and performance, we determined the predominant structural unit of the glycan produced by desiccation-tolerant N. commune DRH-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

Cultures were grown in an air lift fermentor (2 liters) at 25°C in BG110 medium (25a). Both the fermentor and growth medium were autoclaved and subsequently inoculated with N. commune DRH-1 (250 ml) taken from a smaller culture. The cells were grown under an incident photon flux density of 1,750 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 for 2 weeks after which time the culture was harvested by a combination of centrifugation and filtration.

Isolation of the released polysaccharides.

The cell-free supernatant fraction (ca. 1.5 liters) was passed through a tangential-flow filtration concentrator (10,000 molecular weight cutoff [MWCO]; Millipore Corp.), which reduced the volume approximately 10-fold. The solution was freeze-dried to provide an amber powder (1 to 2.5 g), which was dissolved in water (250 ml) and precipitated by pouring the mixture into a rapidly stirred solution of ethanol (95%, 750 ml). The insoluble material was recovered by filtration, washed successively with ethanol and acetone, and subsequently dried to provide a straw-colored material (500 to 750 mg). The material was then dissolved in water (200 ml) and passed through a cation-exchange resin (Dowex; H+ form) to generate the cation-free polysaccharide, which was obtained by freeze-drying as a white mass with the consistency of cotton (300 to 600 mg). Percent recoveries, based on the mass obtained after the tangential-flow filtration, ranged from 30 to 50%.

Formation and isolation of the oligosaccharides.

Oligosaccharide fragments were obtained by partial acid hydrolysis using aqueous 1 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The polysaccharide (300 mg) was dispersed in deionized water (184 ml) by stirring at room temperature (30 min). TFA (16 ml) was added, and the flask was placed in an oil bath (80°C) for 4 h. The mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure at 40°C and further evaporated three times with isopropyl alcohol (100 ml). The materials were then taken up by deionized water (8 ml) and centrifuged. The supernatant was freeze-dried, redissolved in deionized water (3 ml), and separated by gel filtration on a Bio-Gel P2 column (2.5 by 45 cm) eluted with deionized water (0.4 ml/min, 15 min/fraction). Carbohydrates were detected by spot testing (naphthoresorcinol reagent), and fractions were pooled according to thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel (1-butanol–formic acid–H2O; 33:50:17). Selected fractions were further purified a second time on the same column; this time elution was with 0.1 M sodium acetate (NaOAc) (pH 3.7; 0.4 ml/min, 5 min/fraction). Fractions were again pooled based on the TLC results, desalted (Dowex; H+ form), and freeze-dried. The recovered oligosaccharides were then analyzed by gas chromatographic (GC) techniques and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Methanolysis.

Large-scale methanolyses were conducted with stirring in 50-ml screw-cap (Teflon-lined) test tubes at 80°C using methanolic HCl. The reaction solution was prepared by the addition of acetyl chloride (4 ml) to cold anhydrous methanol (MeOH; 21 ml, −40°C). The polysaccharide (100 to 150 mg) was added to this solution, and the mixture was sealed, allowed to warm to room temperature, and placed in an oil bath (80°C) for 16 to 24 h. Processing involved cooling the mixture and subsequently flushing the vial with nitrogen gas (15 min). This was followed by evaporation under reduced pressure (the receiving flask contained a small amount of pyridine to trap the gaseous HCl). Three subsequent additions and evaporations of MeOH provided a syrupy solid which could be purified by silica gel chromatography in acetonitrile-MeOH (90:10 [vol/vol]). The methyl uronates were eluted first, followed by the neutral methyl glycosides. Small-scale hydrolyses were performed in the same fashion to the point of silica gel purification. These syrups were subjected directly to trimethylsilylation (3) and GC analysis (specifics: GC-17A GC [Shimadzu]; Rtx-1 capillary column [30 m by 0.25-mm inside diameter, 0.25-μm thick film; Restek]; He carrier gas; temperature programming: 150°C for 2 min, then to 180°C at 15°C/min, hold for 1 min, then to 240°C at 5°C min; injection [split mode] and detector temperatures were 275°C).

Nosturonic acid structure determination.

The methyl uronate fraction (45 mg) from a large-scale methanolysis was subjected to silica gel chromatography, elution with CHCl3-ethyl acetate (1:1). Collection of the appropriate fractions provided the two anomeric forms. A portion of the mixture was subjected to an overnight NaBH4 reduction in MeOH (36). The crude reaction product was added directly to a small ion-exchange column (Dowex; H+ form), followed by evaporation of the MeOH with a rotary evaporator. Borate was removed from the clear syrup by repeated additions and evaporations of MeOH, providing both anomers of methyl 3-O-[(R)-2-(1-hydroxy)propyl]-d-glucopyranoside (compound 3) in nearly quantitative yield. 13C NMR (CD3OD, 49.0 ppm) results: R-3α, 17.81, 55.45, 62.64, 67.25, 71.33, 73.67, 73.88, 80.19, 83.64, 101.06; R-3β, 17.92, 57.27, 62.70, 67.93, 71.49, 75.04, 78.01, 80.70, 86.75, 105.29.

Synthesis of methyl 3-O-[2-(1-hydroxy)propyl]-d-glucopyranoside.

Diacetone d-glucose (250 mg) was mixed with sodium hydride (150 mg) in dioxane at 65°C (6, 30). 2-Chloropropionic acid (R or S enantiomers; 260 μl) was added after 30 min, and the solution was stirred at 65°C overnight. The reaction mixture was then cooled, and the excess sodium hydride was quenched with water. Extraction with dichloromethane (3×) was followed by acidification of the aqueous phase by the addition of cold 3% HCl (100 ml). The acidified solution was extracted with dichloromethane (3×). This extract was processed to obtain a crude product, which was subjected directly to methanolysis (2 M TFA, 80°C for 16 h). Reaction workup followed by silica gel chromatography (acetonitrile [MeCN]) provided an anomeric mixture which was reduced in a solution containing NaBH4 and NaOCH3 in MeOH (36). The reaction product was purified by passage through a strongly acidic cation-exchange column followed by repeated additions and evaporations with MeOH (residual borate removal). The NMR spectra of the R- and S-hydroxypropyl derivatives were compared directly to those of the material produced by reduction of the native uronate. 13C NMR (CD3OD, 49.0 ppm) results: S-3α, 17.82, 55.55, 62.54, 67.79, 71.68, 73.22, 73.50, 80.43, 84.07, 101.50; S-3β, 17.86, 57.39, 62.63, 67.79, 71.60, 75.00, 77.70, 80.69, 86.89, 105.52.

Nosturonic acid determination in field-isolated materials.

Field samples were pulverized with a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. The powder was suspended in MeOH (10 mg/ml) and extracted for at least 24 h with stirring. The solids were isolated by filtration and then subjected to methanolysis (150 mg), using the procedure described above. Processing provided a syrupy solid which was added to a silica gel column (26 g of silica) packed with acetonitrile. Stepwise elution with MeCN (100 ml) followed by MeCN-MeOH (9:1; 300 ml) provided separation of the uronics from the neutral sugars. The crude uronate fraction was subjected to NMR analysis for detection and estimation of nosturonic acid content.

Methylation analysis.

Carboxyl reduction of the polysaccharide (50 mg) was conducted as described by Kim and Carpita (15). Sequential methylation of the reduced material (1 mg) using NaOH and CH3I was performed as described previously (20). The resulting partially methylated alditiol acetates were analyzed by GC-mass spectrometry (MS), using the temperature program described by York et al. (38) (GC-MS specifics: VG 7070E-HF [double focusing, magnetic sector]; scan range, 35 to 400 atomic mass units at 1.5 s/scan; 70-eV electron impact ionization).

Periodate oxidation.

Periodate oxidation and Smith degradation were performed as described by Severn and Richards (31). The polysaccharide (100 mg) was predispersed in deionized water (25 ml) and then oxidized with NaIO4 (final concentration, 0.05 M; 50 ml) in the dark (4°C, 7 days). The reaction was terminated by the addition of ethylene glycol (0.4 ml), and the oxidized material was reduced with NaBH4 (500 mg; 22°C, 15 h). The excess NaBH4 was decomposed by adjusting pH to 6.5 with 1 M NaOAc. After extensive dialysis (MWCO = 3,500) against deionized water (3 days), the material was freeze-dried (90 mg) and then hydrolyzed with acetic acid (2%, [vol/vol], 100°C, 2 h). The degraded products were evaporated to dryness at 40°C as described above, dissolved in 0.1 M NaOAc (pH 3.7; 3.5 ml), and centrifuged. The supernatant was applied to a Bio-Gel P2 column (2.5 by 45 cm) eluted with 0.1 M NaOAc (pH 3.7; 0.4 ml/min, 15 min/fraction). The fractions were collected according to the TLC results.

Uronosyl cleavage with lithium and ethylenediamine.

Nosturonic acid groups were removed according to the procedure of Mort and Bauer (18), as modified by Lau et al. (16). Polysaccharide (50 mg) was placed in a screw-cap tube along with a stir bar. Anhydrous ethylenediamine (7 ml) was added under argon, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Hexane-washed lithium metal was added (a 3-mm length, 45 mg/cm), and the mixture turned a deep blue after about 5 min. Additional pieces were added over the course of the next 60 min to maintain a deep blue color. The reaction mixture was then cooled in an ice bath, and water was added slowly (5 ml) to quench the excess lithium. Once addition was complete, the solution was transferred to a round-bottom flask and toluene was added. This solution was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the toluene addition and evaporation procedure was repeated two additional times to provide a syrupy solid. The solid was dissolved in water, and the pH was adjusted from 10.5 to 6.4 by the addition of acetic acid. This solution was passed through a cation-exchange resin (200 ml; Dowex 50WX8-200; H+ form), collecting the fractions which were positive to naphthoresorcinol. The combined fractions were freeze-dried to a powder (31 mg) and further purified on a Bio-Gel P2 column with water, collecting the solutions that were eluted prior to the void volume. Freeze-drying provided the “uronosyl-free” polysaccharide (18.7 mg).

Spectroscopy.

NMR spectra of the oligosaccharides were recorded on either a Bruker AM360 or a JEOL Eclipse-plus 500-MHz NMR at 27°C using the software supplied by the manufacturer. Samples analyzed in D2O were freeze-dried from D2O (99.9%) and subsequently dissolved in D2O (600 μl, 99.996%) which contained acetone (0.5 μl) as the internal standard (1H shift, 2.225 ppm; 13C shift, 31.07 ppm). Samples analyzed in CD3OD were referenced to the central solvent peak (1H shift, 3.30 ppm; 13C shift, 49.0 ppm). The 13C NMR spectrum of the purified EPS was obtained on a Varian Unity 400 (D2O, 40°C) using a 10-mm wide-bore probe. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) spectra were obtained with a Kratos Kompact MALDI-TOF MS using a dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix.

Spectrophotometric assays.

Sulfate and phosphate determinations were performed as described previously (1, 33).

RESULTS

Compositional analysis.

The five predominant sugars found in the purified polysaccharide by GC analysis of the trimethylsilyl methyl glycosides were ribose, xylose, glucose, galactose, and uronic acid. Smaller amounts of mannose and glucuronic acid were also found. The molar ratio of ribose to xylose to glucose to galactose to uronic acid was determined to be 1:1:2:1:1, and the neutral carbohydrates were all of the d configuration (39). Spectrophotometric assays for sulfate and phosphate were negative. Silica gel chromatography (MeCN-MeOH) of the methanolysis products provided the crude anomeric uronic acid esters, which were separated into their individual anomers by a subsequent silica gel purification using CHCl3-ethyl acetate. Both anomers contained two carbonyl groups, two methyl esters, and one methyl aglycone. The upfield doublet (3H, 1.4 ppm; J = 8 Hz) which correlated with a quartet (1H, 4.5 ppm) was an isolated spin system indicative of a lactyl moiety. The 1H and homonuclear correlation (COSY) spectra showed a carbohydrate coupling network of a uronic acid with all vicinal ring protons disposed in a trans fashion. The heteronuclear multiple band correlation (HMBC) spectrum provided a strong correlation between the lactyl methine and carbon-3 of the uronate, proving the structure was that of a 3-O-lactyl uronate.

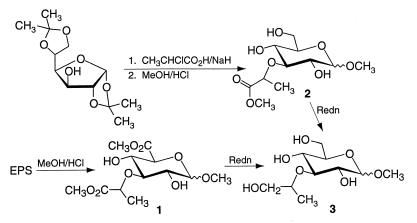

Confirmation of the structure was accomplished by synthesis of a related compound and direct comparison of the NMR spectral properties (Fig. 1). Diacetone d-glucose was alkylated under basic conditions (NaH) with R- and S-2-chloropropionic acid in dioxane (6, 30). Reaction processing and subsequent methanolysis provided the individual R and S diastereomers of methyl 3-O-[1-methoxycarbonylethyl]-d-glucopyranoside as a mixture of anomers. No racemization of the lactyl moiety occurred during the transformation, contrary to a recent report utilizing methyl 2-chloropropionate as the starting halide (14). Reduction with NaBH4 in MeOH-NaOCH3 provided the R and S diastereomers of methyl 3-O-[2-(1-hydroxy)propyl]-d-glucopyranoside with the α-anomer predominating. Comparison of their NMR spectra with those of the anomeric mixture obtained by NaBH4-MeOH reduction of the native uronates provided a match for the α- and β-anomers of methyl 3-O-[(R)-2-(1-hydroxy)propyl]-d-glucopyranoside. The original uronates isolated from the methanolysis of the polysaccharide were therefore the α- and β-anomers of methyl (methyl 3-O-[(R)-1-methoxycarbonylethyl]-d-glucopyranoside)uronate (compound 1) and derived from nosturonic acid (3-O-lactyl d-glucuronic acid; NosA; compound 1a).

FIG. 1.

Synthesis of the α- and β-anomers of methyl 3-O-[2-(1-hydroxy)propyl]-d-glucopyranoside (structure 3), starting from both diacetone d-glucose and the purified polysaccharide. Redn, reduction. See text for details.

Different levels of nosturonic acid were found in both field- and fermentor-grown (supernatant-free) preparations of N. commune subjected a “whole-cell” methanolysis. A 2% nosturonic acid content was found (dry weight basis) in the fermentor-grown material, while a field sample obtained from an ocean beach environment (Topsail Island, S.C.) had a nosturonic acid content of approximately 1%. Only trace levels of nosturonic acid (less than 0.2%) were found in desiccated colonies from a desert region of Mongolia, the original material from which N. commune strain DRH-1 was derived (12). No nosturonic acid could be detected in fermentor-grown N. commune UTEX 584.

Characterization of oligosaccharide fragments.

Since preliminary experiments aimed at degrading the viscous polysaccharide by the use of enzymes were not successful, acid hydrolysis and periodate oxidation were used to fragment the polymer and subsequently elucidate the structure. Mild acid hydrolysis of the polysaccharide (0.1 M TFA, 70°C, 4 h) and analysis of the methanol-soluble fraction provided only d-ribose, in amounts similar to the concentration determined by the compositional analysis. Stronger acid hydrolyses (1 M TFA, 80°C, 4 h) and subsequent size exclusion chromatography (Bio-Gel P2) provided a disaccharide, a trisaccharide, and oligosaccharides that were characterized by NMR spectroscopy (Tables 1 to 3).

TABLE 1.

13C NMR chemical shifts for selected compounds involved in the structural elucidation of the extracellular polysaccharide of N. commune DRH-1c

| Compound | Chemical shift (ppm) for:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | C-4 | C-5 | C-6 | L-1 | L-2 | L-3 | |

| 1α | 100.48 | 71.41a | 82.49 | 71.47a | 71.41a | 172.38 | 19.04 | 77.97 | 177.07 |

| 1β | 104.22 | 73.30 | 84.88 | 71.51 | 75.22 | 171.56 | 19.13 | 78.08 | 177.10 |

| 4 | |||||||||

| Glcp | 101.96 | 73.70 | 76.38 | 70.42 | 76.79 | 61.55 | |||

| α-Xylp | 92.84 | 72.21 | 71.89 | 77.47 | 59.61 | ||||

| β-Xylp | 97.31 | 74.82 | 74.82 | 77.32 | 63.83 | ||||

| 5 | |||||||||

| NosA | 103.84 | 73.20 | 84.79 | 71.58 | 75.27 | 172.98 | 19.24 | 77.90 | 179.02 |

| Glcp | 104.52b | 74.36b | 76.51b | 70.45 | 75.64 | 70.45 | |||

| α-Galp | 93.15 | 69.64 | 70.45 | 79.27 | 70.66 | 61.86 | |||

| β-Galp | 97.23 | 73.05 | 74.04 | 78.22 | 75.13 | 61.69 | |||

| 6 | |||||||||

| NosA | 103.34 | 73.26 | 84.78 | 71.64 | 75.15 | 173.01 | 19.24 | 77.88 | 179.00 |

| Xylp | 104.14 | 73.96 | 76.43 | 70.10 | 65.88 | ||||

| Erythritol | 61.90 | 81.05 | 70.02 | 71.53 | |||||

Assignments may have to be reversed.

Lower-intensity signals for these carbons were also observed (due to the α-Galp anomer): C-1, 104.59 ppm; C-2, 74.44 ppm; C-3, 76.56 ppm.

Shift data were obtained in D2O at 27°C and referenced to internal acetone (31.07 ppm). Methoxyl/methyl ester chemical shifts (ppm); 1α, 53.41, 53.92, 56.40; 1β, 53.42, 53.93, 58.36; 2α, 55.46; 2β, 57.27; 3α: 55.54; 3β: 57.39.

TABLE 3.

Proton and carbon chemical shift data for pentasaccharides 7 and 8a

| Atom | Chemical shift (ppm) for:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | eα | eβ | f | g | h | iα | iβ | |

| C-1 | 103.9 | 104.5 | 100.6 | 101.8 | 92.8 | 97.3 | 102.0 | 103.7 | 104.4 | 93.2 | 97.3 |

| H-1 | 4.60 | 4.68 | 5.46 | 4.57 | 5.22 | 4.62 | 4.56 | 4.52 | 4.71 | 5.30 | 4.63 |

| H-2 | 3.49 | 3.37 | 3.96 | 3.34 | 3.58 | 3.28 | 3.31 | 3.35 | 3.41 | 3.91 | 3.58 |

| H-3 | 3.56 | 3.52 | 3.97 | 3.78 | mb | 3.60 | 3.51 | 3.61 | 3.63 | 3.97 | 3.77 |

| H-4 | 3.74 | 3.44 | 4.28 | 3.66 | mb | 3.86 | 3.41 | 3.87 | 3.72 | 4.25 | 4.19 |

| H-5 | 4.02 | 3.63 | 4.05 | 3.64 | mb | 3.41 | 3.49 | 3.40 | 3.74 | 4.16 | 3.77 |

| H-5′ | mb | 4.09 | 4.14 | ||||||||

| H-6 | 3.90 | 3.75 | 3.80 | 3.75 | 3.97 | 3.74 | 3.77 | ||||

| H-6′ | 4.20 | 3.85 | 3.97 | 3.94 | 4.28 | 3.84 | n.d. | ||||

Anomeric carbon chemical shifts obtained from a 1D-decoupled 13C spectrum of a mixture of both oligosaccharides. Proton chemical shifts were obtained from gradient-enhanced COSY and a phase-sensitive total correlation COSY (TOCSY; 100- and 150-ms spin lock) experiments performed on the same mixture.

Signal overlap, 3.72 to 3.85 ppm. n.d., not determined.

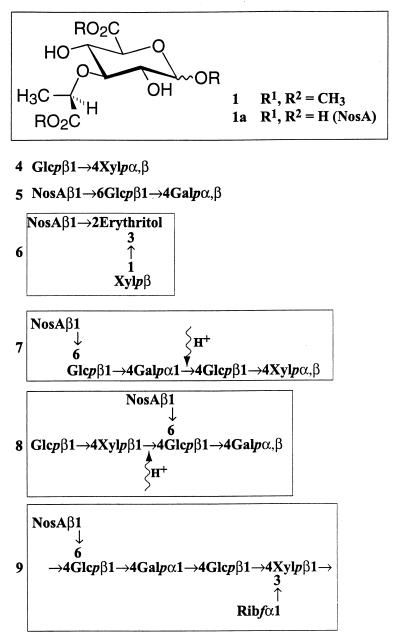

The disaccharide comprised about 10% of the oligosaccharide mixture and was found to contain glucose and xylose. Comparison of the NMR data with that reported for synthetic β-d-Glcp-(1-4)-Xylp (disaccharide 4) (Fig. 2) provided a perfect match (22). The structural assignment of this material was further confirmed by HMBC correlations between the xylose C-4 and the glucose anomeric proton. Methylation analysis confirmed the linkage pattern.

FIG. 2.

Structures of the oligosaccharides isolated from the polysaccharide.

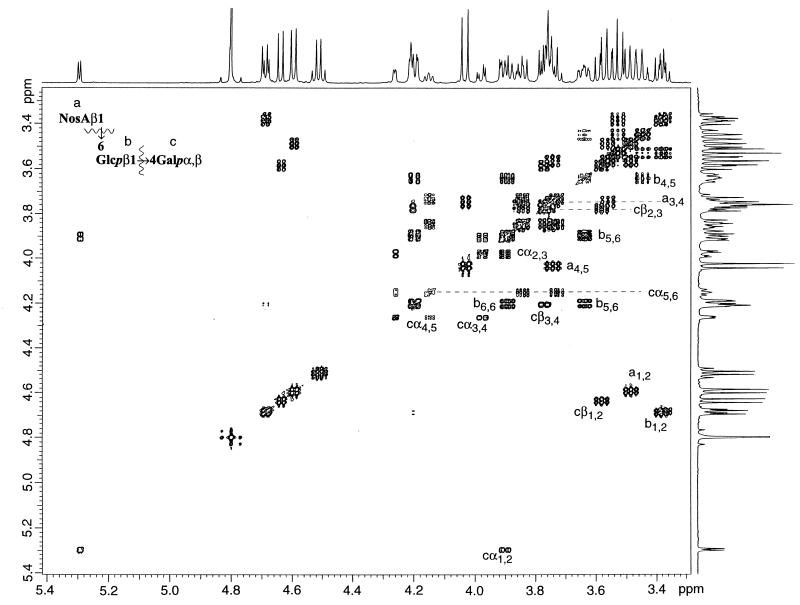

Compositional analysis of the trisaccharide (12% of the hydrolyzate mixture) revealed the presence of glucose, galactose, and nosturonic acid and MALDI-TOF MS gave an ion of the form M plus Na+ at 613.5 amu. The 1H and COSY NMR spectra (Fig. 3) confirmed a trisaccharide structure with galactose at the reducing end. The coupling constants for the remaining anomeric protons were greater than 7 Hz. Since these protons were correlated in the one-band 1H-13C heteronuclear correlation (HMQC) spectrum with carbons with chemical shifts greater than 103 ppm, it was concluded that glucose and nosturonic acid were linked via β-glycosidic bonds.

FIG. 3.

Anomeric and ring proton regions of an absolute-value COSY spectrum (non-PFG) of trisaccharide 5. The important correlations are indicated (see inset for key).

A distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT) experiment revealed a methylene carbon at 70.45 ppm; thus one of the neutral carbohydrates was linked at the 6 position. Analysis of the HMQC spectrum provided correlations between this downfield carbon and the methylene protons of the glucose moiety. The HMBC spectrum provided a correlation between the glucose C-6 and the nosturonic acid anomeric proton, indicating that the nosturonic acid moiety was β-linked to the glucopyranosyl unit at the 6 position. The remaining methylene carbons (61.70 and 61.69 ppm) correlated with the methylene protons of the α- and β-galactopyranosyl moieties, respectively. Further analysis of the spectra showed that the galactose moiety had downfield shifts for C-4 (α, 79.27 ppm; β, 78.22 ppm), indicating a glycosidic bond at that position. The HMBC spectrum provided a correlation between the glucose anomeric proton and the two galactose H-4 protons (α- and β-anomers), confirming this glycosidic linkage. The structure of the trisaccharide was therefore β-d-NosA-(1-6)-β-d-Glcp-(1-4)-d-Galp (trisaccharide 5).

Periodate oxidation, reduction, and Smith degradation proved to be central in ascertaining the structure of the polysaccharide. The major product of the treatment regimen was a material which displayed 18 carbons in the 13C spectrum, 3 of which were methylene carbons (61.9, 65.88, and 71.53 ppm). Since nosturonic acid does not contain vicinal diols, it should be resistant to periodate oxidation, and indeed its presence was clearly seen by compositional analysis as well the 1H and 13C spectra. The COSY spectrum revealed the complete coupling pattern for nosturonic acid as well as a pentose, which was confirmed to be d-xylopyranose by compositional analysis. This left four carbons to be accounted for, two of which were methylenes (61.90 and 71.53 ppm). As trisaccharide 5 has nosturonic acid attached to the 6 position of a β-d-glucopyranosyl moiety, if the 2 and 3 positions of glucose did not have glycosidic bonds, the Smith degradation should have led to the formation of erythritol. Indeed, compositional analysis confirmed the presence of erythritol, leaving the possibilities that xylose was linked to either nosturonic acid or the erythritol moiety. Since the HMBC spectrum provided strong correlations between an erythritol methine carbon (81.50 ppm) and the anomeric proton of the xylopyranosyl unit, as well as between an erythritol methylene (71.53 ppm) and the anomeric proton of the nosturonic acid, the structure was proved to be that of compound 6 (Fig. 2). The presence of a xylopyranose unit in this structure without any other groups attached implies that the original polysaccharide had a d-xylopyranosyl unit that did not have vicinal diols and was β-(1-4)-linked to a d-glucopyranosyl group. This finding will become important when the location of the ribose moiety is discussed.

Analysis of the higher-molecular-weight oligosaccharides produced by dilute acid hydrolysis provided additional insight into the polysaccharide structure. It was ascertained from a compositional analysis of these oligosaccharides that glucose, galactose, xylose, and nosturonic acid were found invariably in a 2:1:1:1 ratio (respectively). Significant quantities of ribose lacked all oligosaccharide fractions tested. This indicates that in the original polysaccharide the ribose unit was attached as a pendant group in the furanosidic form (a linkage unstable to acidic conditions). Furthermore, the results of the compositional analysis of the “ribose-free” oligosaccharides match the molar amounts that would be obtained from a 1:1 mixture of disaccharide 4 and trisaccharide 5. This strongly suggests that such a pentamer would be the repeat unit of the ribose-free polysaccharide.

Unfortunately, attempts at obtaining pure individual higher oligosaccharides failed; i.e., there was never a complete separation of individual oligosaccharides greater in size than the trisaccharide. NMR analysis of the oligosaccharide fraction that was eluted just prior to the trisaccharide indicated a mixture of predominantly two oligosaccharides. This crude mixture comprised 19% of the total hydrolysate. MALDI-TOF MS gave an ion of the form M plus Na+ at 908 amu, indicating pentasaccharides containing nosturonic acid, a pentose, and three hexoses.

Based upon compositional analysis and the MALDI-TOF results, it was assumed that pentamer mixture is composed of a combination of disaccharide 4 and trisaccharide 5. Since periodate oxidation product 6 contained a β-d-xylopyranosyl group linked to erythritol, the xylose moiety must be linked to glucose via C-4 since any other linkage to glucose would not have afforded erythritol. If xylose had been linked to galactose, the xylopyranosyl moiety would have been attached to threitol. Combining saccharides 4 and 5 via a β-d-xylopyranosyl bond to the 4 position of the glucose unit of trisaccharide 5 gives pentasaccharide 7 (Fig. 2). If structure 7 represents the predominant repeat unit of the ribose free EPS, the last remaining glycosidic bond to be determined is the one between galactose and glucose.

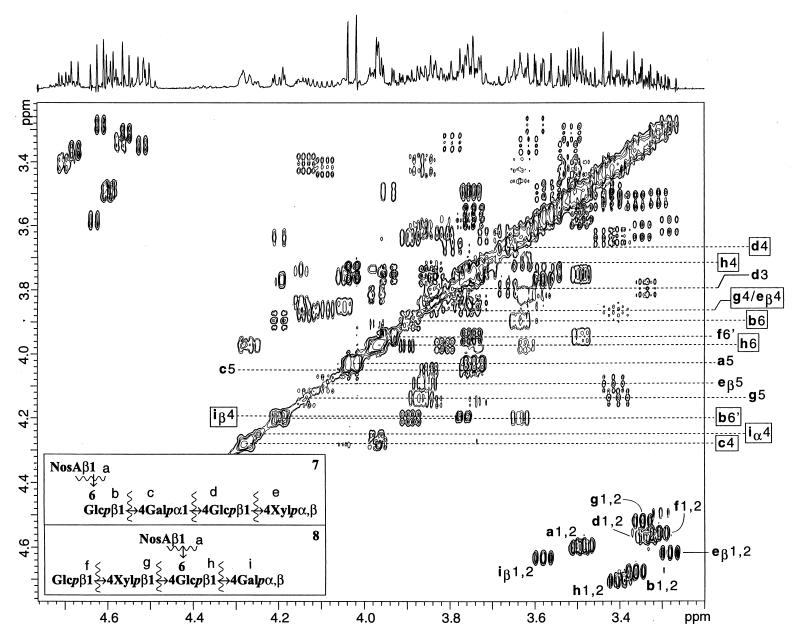

The 1H NMR pentamer spectrum showed three α-anomeric protons, and two of these doublets and their associated coupling networks matched with the α-galactopyranose and α-xylopyranose H-1 protons observed in saccharides 4 and 5. That these two resonances disappeared upon an aqueous borohydride reduction indicates that they are reducing end α-anomeric protons. The borohydride-resistant α-anomeric proton correlated with the most upfield glycosidic anomeric carbon (100.6 ppm) and matched the anticipated chemical shifts and proton coupling network for an α-d-galactopyranosyl moiety (Table 3; Fig. 4) (9). Furthermore, the gradient-enhanced HMBC experiment showed a correlation between the α-d-galactopyranosyl anomeric proton and the C-4 carbon of a β-d-glucopyranosyl unit (77.6 ppm) (21). Thus the two predominant oligosaccharides in the mixture were pentamers 7 and 8, which represent the repeat unit of the ribose-free polysaccharide. The fact that two pentamers were obtained by size exclusion chromatography is most likely due to the similar acid hydrolysis rates of position 4-linked α-galactopyranosyl and β-xylopyranosyl glycosidic bonds (34).

FIG. 4.

The β-anomeric and ring proton regions of a 500-MHz gradient-enhanced absolute-value COSY spectrum of a mixture of pentasaccharides 7 and 8. The boxed assignments indicate protons with HMBC correlations to anomeric carbons on adjacent rings (see inset for key).

The last remaining assignment was the attachment of ribose. As was previously mentioned, the absence of ribose in significant amounts in any of the oligosaccharides supports a structure where a ribofuranosidic group is linked to the backbone of the polysaccharide. Methylation analysis of the EPS revealed a terminal ribofuranose, further supporting this mode of attachment. In addition, methylation analysis indicated that the xylopyranose moiety was 3,4-linked. This linkage pattern, as well as the structure of the periodate oxidation product (compound 6), supports a ribofuranosyl group at position 3 of xylose.

Proof of ring size and linkage stereochemistry was obtained in two ways. First, a 13C NMR experiment on the intact polysaccharide was performed using a 10-mm wide-bore probe (40°C). The spectrum indicated the absence of pendant acyl groups (acetate, succinate) and acetals. Signals at 84.89 and 85.81 ppm were readily assigned to C-3 of NosA and C-4 of Ribf, respectively. The lack of any signal greater than 104.86 ppm typically rules out a β-linkage (26, 29), leaving α-d-Ribf as the only possible mode of attachment. Additional proof for this assignment was obtained from the NMR analysis of the polysaccharide obtained after lithium and ethylenediamine treatment, a reaction which removes uronosyl moieties (16, 18). A downfield doublet was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum (5.46 ppm; J = 4.4 Hz), and this proton correlated in an HMQC experiment with a carbon at 103.8 ppm. The chemical shifts and coupling constants found for the anomeric position match the values anticipated for α-ribofuranosides (2, 29), the typical coupling constant for β-ribofuranosides being 1 to 1.2 Hz (2, 8, 29). Furthermore, the COSY spectrum of this material revealed an H-4 resonance at 4.4 ppm, and this proton correlated with a carbon at 85.5 ppm in an HMQC experiment, clear evidence of a furanosyl ring. Thus the structure of the repeat unit contains an α-ribofuranosyl moiety as shown in Fig. 2 (compound 9).

DISCUSSION

Although lactyl-containing uronic acids were reported previously in cyanobacteria (7), the 3-O-lactyl glucuronic acid described here was reported only once before: in the exopolysaccharide produced by a strain of the bacterium Alteromonas (NMR spectral data not determined) (6). This organism was originally found on the epidermis of a worm (Avinella caudata) growing near a deep sea hydrothermal vent in the eastern Pacific Ocean (6). Since the uronic acid is present in an organism as globally significant as N. commune, we have named this compound nosturonic acid (NosA). Since both Alteromonas and N. commune are found in so-called “extreme environments,” nosturonic acid or uronic acids with lactyl moieties may play pivotal roles in the ability of organisms to survive under harsh conditions. Such a functional group can act as a “spacer arm” or “linker,” and could aid in adherence of the EPS to inorganic or organic surfaces (biofilms) and/or allow covalent attachment of UV-absorbing pigments or adjacent polysaccharide chains (molecular scaffold).

The field samples that tested positive for the presence of nosturonic acid belong to “form species” N. commune as defined through group I intron analysis (D. Wright, T. Prickett, R. F. Helm, and M. Potts, submitted for publication). Nosturonic acid could not be detected in N. commune UTEX 584 when grown under the same conditions used for N. commune DRH-1. N. commune UTEX 584 is a culture collection strain of unknown origin (and probably incorrectly named) that does not belong in the form species group on the basis of intron analysis (Wright et al., submitted). As such nosturonic acid may be a marker for the EPS of a restricted group of cyanobacteria.

Previous reports on the extracellular polysaccharides of cyanobacteria have suggested that their structures may not be comparable to those of algae, bacteria, or fungi (19). In essence the question of regularity (repeat unit or averaged structure) is considered open, as conflicting evidence has been reported. In our work it appears that the N. commune EPS does contain a predominant repeat unit under the specific conditions used in our experiments. Since mannose and glucuronic acid were found in the original EPS preparations but were not found in any of the oligomers we have investigated, we assume the these carbohydrates were derived from degraded cellular material and/or capsular polysaccharide. The possibility that these groups are also present in the EPS in very small amounts does, however, exist. In this context it should be pointed out that the physical properties of the EPS change according to environmental conditions and that growth for periods greater than the 2-week period used here provides a slightly different polysaccharide (data not shown). This suggests that there is some degree of flexibility in the sequence of, and control over, the polysaccharide assembly process. As a consequence, cyanobacteria may produce a polysaccharide with a specific linkage pattern under one set of environmental conditions but as the environmental cue changes (extreme heat, lack of water) the polysaccharide structure could be modified to insure the viability of the organism. This makes the structural analysis of cyanobacterial polysaccharides quite challenging especially for field materials, as they may contain several polysaccharides, each representing the recent environmental history of the location. Such behavior is not without precedent (5), and, as we have reported here, different amounts of nosturonic acid were measured in the field-grown materials of N. commune from different geographic locations.

The presence of ribose in the N. commune EPS is a novel feature. There are scattered reports of ribose in the extracellular polysaccharides of cyanobacteria (5), but this is the first unambiguous identification. Ribose is well known as a component of the lipo- and capsular polysaccharides from many gram-negative bacteria, where it is found exclusively as a β-furanosyl residue (8, 17, 37). Why does a polysaccharide involved in the protection of an organism from an extreme environment have a carbohydrate as labile as ribose? One could theorize that the moiety protects neighboring glycosidic bonds from the more common glycan hydrolases. Under this scenario, the selective removal of the ribose group should leave the polysaccharide more susceptible to enzymatic depolymerization (Z. Huang, T. Prickett, M. Potts, and R. F. Helm, submitted for publication). Another possibility is that, because N. commune is restricted to neutral and/or alkaline environments, the acid-labile nature of ribose is never an important factor. Autoclaving the crude EPS results in a decrease in solution viscosity, and free ribose was detected in the resulting aqueous solution by TLC. This qualitative observation supports the possibility that ribose is partially responsible for the gelatinous consistency of the native material (viscosity modifier).

Colonies of N. commune are a conspicuous feature of nutrient-poor terrestrial soils on all continents from the tropics to the polar regions (24). Desiccated crusts are brittle and friable but have the consistency of cartilage when rehydrated. The massive and rapid swelling of desiccated colonies following rainfall is sufficiently striking that it was even the subject of medieval folklore (25). These rheological properties of the glycan, as well as its resistance to degradation in situ, its ability to prevent membrane fusion upon removal of water, its capacity to immobilize the water stress protein Wsp and UV-absorbing pigments, and its significant contribution to the dry weight of colonies emphasize the pivotal role for this biopolymer in the biology of N. commune, particularly the capacity for desiccation tolerance. The solving of the structure of the glycan provides crucial data for investigating how its synthesis is regulated, how it is modified through environmental stress, and how it interacts with other components of the response to desiccation (secreted UV-absorbing pigments and carbohydrate-modifying enzymes).

TABLE 2.

1H NMR data for compounds involved in the structural elucidation of the extracellular polysaccharide of N. commune DRH-1b

| Compound | H-1 | H-2 | H-3 | H-4 | H-5a | H-5b/6a | H-6b | L-1 | L-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1α | 4.838 | 3.612–3.695 | 4.217 | 1.419 | 4.466 | ||||

| 3.5, d | 9.6, d | 7.0, d | 13.9, q | ||||||

| 1β | 4.412 | 3.374 | 3.511 | 3.687 | 4.072 | 1.425 | 4.479 | ||

| 7.8, d | dd | 9.2, t | 9.0, dd | 9.9, d | 7.0, d | 13.9, q | |||

| 4 | |||||||||

| Glcp | 4.532a | 3.277 | 3.483 | 3.389 | 3.461 | 3.918 | 3.723 | ||

| 7.8, d | m | 9.2, t | m | m | 2.2, dd | 6.0, dd | |||

| α-Xylp | 5.189 | 3.551 | 3.770 | 3.812 | 3.835 | 3.750 | |||

| 3.9, d | 9.2, dd | m | m | m | m | ||||

| β-Xylp | 4.590 | 3.254 | 3.570 | 3.834 | 4.064 | 3.389 | |||

| 7.8, d | m | 9.3, t | m | 5.3, 11.7 | m | ||||

| 5 | |||||||||

| NosA | 4.564 | 3.459 | 3.536 | 3.718 | 4.004 | 1.462 | 4.483 | ||

| 7.9, d | 9.1, dd | t | m | 9.9, d | 7.0, d | 14.0, q | |||

| Glcp | 4.659a | 3.359a | 3.502 | 3.420 | 3.611 | 4.172 | 3.866 | ||

| 7.9, d | 9.3, dd | 9.1, t | m | m | m | m | |||

| α-Galp | 5.267 | 3.875 | 3.950 | 4.233 | 4.123 | 3.816 | 3.698 | ||

| 3.8, d | 10.2, dd | 3.0, dd | 3.3, bd | 6.3, bt | |||||

| β-Galp | 4.607 | 3.556 | 3.745 | 4.177 | 3.730 | 3.815 | 3.733 | ||

| 7.9, d | 10.1, dd | 3.2, dd | m | m | m | m | |||

| 6 | |||||||||

| NosA | 4.595 | 3.476 | 3.559 | 3.713 | 4.018 | 1.463 | 4.490 | ||

| 7.9, d | t | 9.2, t | 9.5, t | 10.1, d | 7.0, d | 14.0, q | |||

| Xylp | 4.519 | 3.286 | 3.440 | 3.613 | 3.942 | 3.297 | |||

| 7.9, d | m | 9.1, t | m | 5.5, 11.5 | m | ||||

| Erythritol | 3.754 | 3.859 | 3.996 | 4.102 | |||||

| 5.2, 12.1 | m | m | 2.7, 10.7 | ||||||

| 3.814 | 3.830 | ||||||||

| m | m | ||||||||

Shifts could be observed for the individual α- and β-anomers. The β-anomer data are reported in the table; α-anomer: 4, H-1 (4.527 ppm; J = 7.8 Hz); 5, H-1 (4.654 ppm; J = 7.9 Hz, d); H-2 (3.346 ppm; J = 9.3, dd). Methoxyl/methyl ester chemical shifts (ppm): 1α, 3.427, 3.764, 3.828; 1β, 3.542, 3.765, 3.830.

Shift data for were obtained in were obtained in D2O at 27°C and referenced to internal acetone (2.225 ppm). Coupling constants are in Hz.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Naval Research Laboratories (DARPA, N00173-98-1-G005-LOG) as well as the National Science Foundation (IBN 9513157). D.E., H.L., and W.P. were supported in part by the undergraduate research program of the Department of Biochemistry.

We thank Kratos Analytical (Brian Stahl) for performing the MALDI-TOF analyses and Tom Glass (Department of Chemistry, Virginia Tech) for helpful discussions concerning the NMR experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames B N. Assay of inorganic phosphate, total phosphate and phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 1966;8:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angyal S J. Hudson's rules of isorotation as applied to furanosides, and the conformations of methyl aldofuranosides. Carbohydr Res. 1979;77:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleton J, Mejanelle P, Sansoulet J, Goursaud S, Tchapla A. Characterization of neutral sugars and uronic acids after methanolysis and trimethylsilylation for recognition of plant gums. J Chromatogr A. 1996;720:27–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Böhm G A, Pfleiderer P, Böger P, Scherer S. Structure of a novel oligosaccharide-mycosporine-amino acid ultraviolet A/B sunscreen pigment from the terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8536–8539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DePhillipis R, Vincenzini M. Exocellular polysaccharides from cyanobacteria and their possible applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:151–175. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubreucq G, Domon B, Fournet B. Structure determination of a novel uronic acid residue isolated from the exopolysaccharide produced by a bacterium originating from deep sea hydrothermal vents. Carbohydr Res. 1996;290:175–181. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garozzo D, Impallomeni G, Spina E, Sturiale L. The structure of the exocellular polysaccharide from the cyanobacterium Cyanospira capsulata. Carbohydr Res. 1998;307:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(98)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gil-Serrano A M, Rodríguez-Carvajal M A, Tejero-Mateo P, Espartero J L, Thomas-Oates J, Ruiz-Sainz J E, Buendia-Clavería A M. Structural determination of a 5-O-methyl-deaminated neuramic acid (Kdn)-containing polysaccharide isolated from Sinorhizobium fredii. Biochem J. 1998;334:585–594. doi: 10.1042/bj3340585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruter M, Leeflang B R, Kuiper J, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G. Structural characterization of the exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus delbruckii subspecies bulgaricus RR grown in skimmed-milk. Carbohydr Res. 1993;239:209–226. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84216-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill D R, Keenan T W, Helm R F, Potts M, Crowe L M, Crowe J H. Extracellular polysaccharide of Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria) inhibits fusion of membrane vesicles during desiccation. J Appl Phycol. 1997;9:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill D R, Hladun S L, Scherer S, Potts M. Water stress proteins of Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria) are secreted with UV-A/B-absorbing pigments and associate with 1,4-β-d-xylanohydrolase activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7726–7734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill D R, Peat A, Potts M. Biochemistry and structure of the glycan secreted by desiccation-tolerant Nostoc commune (cyanobacteria) Protoplasma. 1994;182:126–148. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horodyski R J, Bauld J, Lipps J H, Mendelson C V. Preservation of prokaryotes and organic-walled and calcareous and siliceous protists. In: Schopf J W, Klein C, editors. The proterozoic biosphere. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Impallomeni G. On the presence of 4-O-(1-carboxyethyl)-mannose in the capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype 3. Carbohydr Res. 1998;312:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J-B, Carpita N C. Changes in esterification of the uronic-acid groups of cell-wall polysaccharides during elongation of maize coleoptiles. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:646–653. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau J M, McNeil M, Darvill A G, Albersheim P. Selective degradation of the glycosyluronic acid residues of complex carbohydrates by lithium dissolved in ethylenediamine. Carbohydr Res. 1987;168:219–243. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindberg B. Components of bacterial polysaccharides. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 1990;48:279–318. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(08)60033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mort A J, Bauer W D. Application of two new methods for cleavage of polysaccharides into specific oligosaccharide fragments. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:1870–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morvan H, Gloaguen V, Vebret L, Joset F, Hoffman L. Structure-function investigations on capsular polymers as a necessary step for new biotechnological applications: the case of the cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1997;35:671–683. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Needs P W, Selvendran R R. An improved methylation procedure for analysis of complex polysaccharides including resistant starch and a critique of the factors which lead to undermethylation. Phytochem Anal. 1993;4:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osman S F, Fett W F, Irwin P, Cescutti P, Brouillette J N, O'Connor J V. The structure of the exopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain H13. Carbohydr Res. 1997;300:323–327. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrakova E, Krupova I, Schraml J, Hirsch J. Synthesis and C-13 NMR-spectra of disaccharides related to glucoxylans and xyloglucans. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1991;56:1300–1308. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potts M. Desiccation tolerance of procaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:755–805. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.755-805.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potts, M. In B. A. Whitton and M. Potts (ed.), Ecology of cyanobacteria: their diversity in time and space, in press. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 25.Potts M. Etymology of the genus name Nostoc. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:584. [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J B, Herdman M, Stanier R Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie R G S, Cyr N, Korsch B, Koch H J, Perlin A S. Carbon-13 chemical shifts of furanosides and cyclopentanols. Configuration and conformational influences. Can J Chem. 1975;53:1424–1433. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherer S, Potts M. Novel water-stress protein from a desiccation-tolerant cyanobacterium—purification and partial characterization. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12546–12553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schopf, J. W. In B. A. Whitton and M. Potts (ed.), Ecology of cyanobacteria: their diversity in time and space, in press. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 29.Serianni A S, Barker A. [13C]-Enriched tetroses and tetrofuranosides: an evaluation of the relationship between NMR parameters and furanosyl ring conformations. J Org Chem. 1984;49:3292–3300. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Severn W B, Richards J C. A novel-approach for stereochemical analysis of 1-carboxyethyl sugar ethers by nmr-spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1114–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severn W B, Richards J C. Structural analysis of the specific capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype-2. Carbohydr Res. 1990;206:311–332. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)80070-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirkey B, Kovarcik D P, Wright D J, Wilmouth G, Prickett T F, Helm R F, Gregory E M, Potts M. Active Fe-containing superoxide dismutase and abundant sodF mRNA in Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria) after years of desiccation. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:189–197. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.189-197.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terho T T, Hartiala K. Method for determination of the sulfate content of glycosaminoglycans. Anal Biochem. 1971;41:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timell T E. The acid hydrolysis of glycosides. I. General conditions and the effect of the nature of the aglycone. Can J Chem. 1964;42:1456–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitton, B. A., and M. Potts. In B. A. Whitton and M. Potts (ed.), Ecology of cyanobacteria: their diversity in time and space, in press. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 36.Wolfrom M L, Thompson A. Reduction with sodium borohydride. Methods Carbohydr Chem. 1963;2:70. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolucka B, Hoffmann E. The presence of β-d-ribosyl-1-monophosphodecaprenol in mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20151–20155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.York W S, Darvill A G, McNeil M, Stevenson T T, Albersheim P. Isolation and characterization of plant cell walls and cell wall components. Methods Enzymol. 1985;118:3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 39.York W S, Hantus S, Albersheim P, Darvill A G. Determination of the absolute configuration of monosaccharides by 1H NMR spectroscopy of their per-O-(S)-2-methylbutyrate derivatives. Carbohydr Res. 1997;300:199–206. [Google Scholar]