Summary

Background

Ventriculitis is an infection of the ventricular system of the central nervous system associated with neurosurgery and/or indwelling medical devices mainly caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci and increasingly by Gram-negative bacilli and other Gram-positive bacteria. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the neurosurgery department University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) have treatment guidelines for ventriculitis which recommend antimicrobials and device removal.

Methods

Data on ventriculitis cases, their management and outcomes were collected from electronic laboratory and hospital records as well as patients' paper records from 2009 to 2019. Cases included patients with CSF shunts or external ventricular drainage. The management of the cases was then compared to both Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and UHCW guidelines. The data collected included the causative organisms and the use of inappropriate antimicrobials. The cost of inappropriate antimicrobials was calculated.

Results

99 patients with microbiologically confirmed ventriculitis were identified. Some cases had multiple devices and the total number of devices was 105.98% of cases had medical device removal as part of their care. Only 50% and 56% of cases had antimicrobial treatment which was compliant with local (UHCW) and IDSA guidelines, respectively. The most frequently inappropriate antimicrobials used were meropenem and linezolid, at an estimated cost of £201,172 over 10 years. The most frequently isolated organisms were coagulase negative staphylococci. Mortality rate was estimated at 14% of cases.

Conclusions

We report the first analysis of the management of ventriculitis cases at UHCW over a 10-year period and demonstrate the importance of antimicrobial stewardship. We also report the local epidemiology of causes of ventriculitis at UHCW which will guide the empirical treatment of ventriculitis at UHCW.

Key words: Ventriculitis, Antimicrobial stewardship, Neurosurgery, CSF shunts, External-ventricular drainage

Introduction

Ventriculitis is an infection of the ventricular system of the central nervous system. Most commonly it occurs as a complication of neurosurgery, but also after head injury [1,2]. Ventriculitis typically occurs in association with medical devices, such as external-ventricular drains (EVD) or ventriculoperitoneal shunts (VP shunts). EVDs are used for short-term regulation and monitoring of intracranial pressure, for the administration of certain medications and the collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples [3]. VP shunts are used for long term regulation of intracranial pressure, particularly in patients with hydrocephalus. Ventriculitis is difficult to define as the clinical presentation varies depending on the causative organism and the clinical scenario. A combination of symptoms, laboratory findings, imaging findings and clinical judgement are used to make a diagnosis [4]. The epidemiology of ventriculitis varies between location and the type of neurological device used, with some studies demonstrating a 20% incidence rate [5]. University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) has a busy neurosurgical unit, and is estimated to carry out over 3000 neurosurgical procedures per year [6]. Currently, the local epidemiology of ventriculitis has not been investigated previously.

The management of ventriculitis can be lengthy and expensive and ventriculitis can lead to serious long-term sequelae and even result in death. [[7], [8], [9]].

Device-associated ventriculitis is complicated by biofilm formation on the devices with organisms becoming phenotypically resistant to antimicrobials while remaining sensitive in their planktonic form [10,11]. Studies show that coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus are the most frequent causes of ventriculitis but multi-drug resistant Gram-negative organisms are increasingly becoming important [[12], [13], [14]].

The treatment of ventriculitis at UHCW utilises a multidisciplinary team approach as recommended by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and local trust guidelines [4,15]. Treatment relies on removal of infected device and broad-spectrum antimicrobials which should be modified according to culture results. Antimicrobial treatment is generally given for at least 14 days post CSF sterility taking into account the clinical response and causative organism.

Inappropriate antimicrobial use promotes antimicrobial resistance [16], a global threat on a par with climate change [17]. Good antimicrobial stewardship requires that the antimicrobial choice is evidence-based [18]. Ventriculitis, as a healthcare-associated infection is likely to be caused by multi-drug resistant organisms and thus poses a challenge for treatment [[19], [20], [21]]. Furthermore, the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials in these cases causes harm to the patient's gut microbiome. [[22], [23], [24], [25]].

We analysed the management of culture proven ventriculitis cases over a 10-year period from 2009 to 2019. The aim of this study was twofold. Firstly, to compare the management of ventriculitis cases at UHCW with IDSA and UHCW treatment guidelines and to identify areas for improvement in treatment of ventriculitis at UHCW. Secondly, to document the epidemiology of microbiologically proven ventriculitis in UHCW. This information will be used to revise the ventriculitis empirical antimicrobial treatment guidelines at UHCW.

To the best of our knowledge there has been no published study carried out on the treatment of all microbiologically proven cases of ventriculitis, although audits of EVD-related infections have been conducted [[26], [27], [28]].

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Warwick Medical School (BSREC Number- BSREC- CDA- SSC2-2019-33).

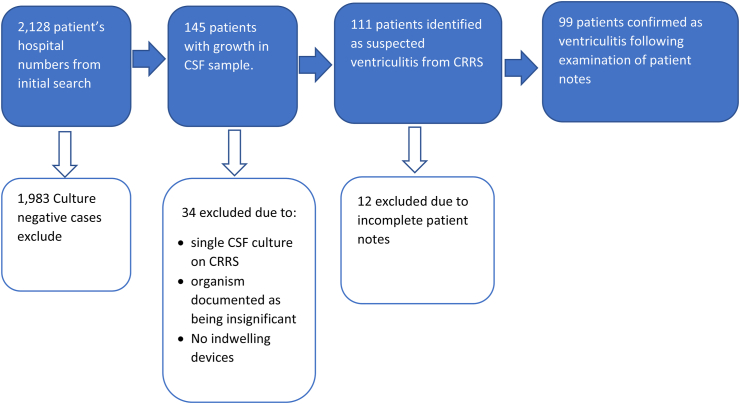

To identify microbiologically proven ventriculitis, a search of the microbiological database at UHCW for the period 2009 to 2019 was conducted according to the criteria in Table I and further searches were carried out in UHCW's clinical result reporting system (CRRS) according to criteria and methodology in Table II. CRRS is an electronic patient record system which captures results of all patient investigations as well as patient correspondence between healthcare providers. The paper notes of patients identified as having microbiologically proven ventriculitis were examined to determine antimicrobials given and duration of treatment (Figure 1). There was cross reference between the prescription charts and the time of the ventriculitis episode to ensure that the treatment given was for ventriculitis. The first and last day of the antimicrobial administration were used to calculate the length of the course using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft office 365®). Interruptions to antimicrobial administration were recorded.

Table I.

Search criteria used for initial search to identify probable cases of ventriculitis

| Search criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| CSF samples received within the last 10 years | In order to limit the number of cases to a manageable number and to minimise amount of patient data collected. |

| Patient's located to neurosurgical ward 43 | • Ward 43 is the neurosurgical wards at UHCW• Ventriculitis is a highly complex and specialised condition so patients should be treated with facilities equipped for this. |

| Exclusion of organisms which cause acute meningitis e.g. Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae | Ventriculitis is an opportunistic infection occurring as a complication of neurological disease or treatment and acute meningitis organisms are not considered to be ventriculitis. |

Table II.

Criteria and methodology for examination of patient electronic health records on the CRRS system at UHCW

| Search criteria | Method of searching |

|---|---|

| Criteria for ventriculitis | Cases were not considered ventriculitis if there were no indwelling devices used, or electronic documentation made no reference to ventriculitis or healthcare associated meningitis Exclusion criteria: Negative culture |

| Date of first CSF sample positive | Microbiology section of CRRS was filtered to only include CSF samples. These were then manually searched for the first sample which had an isolated organism |

| Date at which CSF samples become negative | Of the CSF samples, the subsequent samples were examined to determine when they became negative (i.e. No growth at 48 hours reported on the CSF microbiology results). Once a negative sample was identified, we recorded this and continued to examine the remaining CSF samples. To aid in determining the date of resolution we also collected CSF white cell count (WCC), CSF protein and CSF glucose where these were available. Recurrent infection was defined as 28 days from first positive CSF i.e. if the sample became negative during this time but then became positive again, this was considered a recurrent infection |

| Organism Identified | Positive CSF samples had the organism(s) recorded into Microsoft Excel 365©. Organisms were given a two-letter key. Where the comment provided by microbiology suggested the isolate was of questionable significance, it was considered positive if the criteria they set out in the result comment was met, or if the medical device was removed, or if the patient received treatment for this infection. Exclusion criteria: Single CSF sample sent, Documentation of organism as insignificant, no intracranial devices present |

| Removal of intracranial device | The “theatre” tab of CRRS was examined to determine if devices were present and if they were removed. The date at which this procedure was done was also recorded. We also recorded what the type of intracranial device was to assist with analysis of antimicrobial selection. Occasionally there was a lack of documentation for removal of devices. When this was the case, the following judgements were made:

|

| Mortality | Patient records were examined to determine if the patient was deceased. In this case, it was only recorded if the patient had died whilst receiving treatment for ventriculitis or it was stated on the documentation for the cause of death. |

Figure 1.

Data collection processes showing inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Patients with incomplete notes around the ventriculitis episode were excluded from the study. Notes were considered incomplete where older volumes were unable to be sourced for a variety of reasons such as being at a different hospital site.

An attempt was made to determine the likelihood of contamination of a CSF samples by examination and documentation of CSF samples being taken aseptically. Where antimicrobials were administered via the intraventricular (IT) route, notes were examined for documentation of adherence to strict infection prevention and control procedures as recommended by the guidelines.

The duration of treatment was calculated by taking the day of culture negative CSF to the day antimicrobials were stopped. Mortality from ventriculitis was determined if ventriculitis was documented as a cause of death in the medical notes. Death certificates were not examined.

Data analysis

To simplify the data analysis and improve accuracy, a tool was created which condensed the guidelines to antimicrobial name, indication, route of administration and treatment duration (Table III). IDSA guidelines include some antimicrobials which were not available at UHCW such as oxacillin, and therefore this table reflects feasible antimicrobial choice based on the local formulary. Each patient's treatment was compared to both UHCW and IDSA guidelines using this tool. For antimicrobial use that deviated from the guidelines, the CRRS was reviewed for allergy to antimicrobials and the antimicrobial sensitivities. Duration of treatment was calculated by taking the day of culture negative CSF to the day when the antimicrobials were stopped. Both sets of guidelines base duration of treatment on the organism isolated. Initially this is based on the Gram stain results until a final identification is obtained. The number of caseswhich met the treatment duration of 14 days for Gram-positive organisms and 21 days for Gram-negative organisms (recommended treatment duration during the study period) was then calculated. Where there was deviation from guidelines for antimicrobial choice or course length, the medical notes were examined for the rationale. Where this was not evident, it was considered inappropriate in this study.

Table III.

Analysis tool which was used to assist in the comparison of antimicrobial choice and duration of treatment

| IDSA guidelines | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Antimicrobial (a) | Antimicrobial (b) | Antimicrobial (c) | Antimicrobial (d) | Duration |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Vancomycin∗ | Rifampicin | Linezolid | 10–14 days | |

| Coagulase negative Staphylococci | Vancomycin∗ | Rifampicin | |||

| Enterococcus faecalis | Linezolid | ||||

| Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) acnes | Penicillin G | ||||

| Gram negative bacilli | In vitro sensitivities | ceftriaxone | Cefotaxime | 10-14/21 days | |

| Pseudomonas spp. | Cefepime | ceftriaxone | Meropenem | Aztreonam | |

| ESBL | Meropenem | ||||

| Acinetobacter spp. | Meropenem | Polymyxin B | Colistin | ||

| Resistant Gram-negative bacilli | Meropenem | ||||

| Candida spp. | Amphotericin | Fluconazole | 5-flucytosine | ||

| Antimicrobial (a) is first line, with alternatives (b-d) as options where antimicrobial (a) is not appropriate. In the case of rifampicin, this is used in combination and not in isolation. ∗Vancomycin can be given IV with IT being reserved for cases responding poorly to systemic antimicrobial. These guidelines have been modified to reflect what is available at UCHW based on trust formulary, for example nafacillin is first line for methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus in the IDSA guidelines but is not available at this hospital. ESBL = Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producers | |||||

| UHCW guidelines | |||||

| Device | Organism | Antimicrobial (a) | Antimicrobial (b) | Antimicrobial (c) | Duration |

| EVD | Coagulase negative Staphylococci | Vancomycin (IT) | Time for device in situ, sterile CSK before new EVD/shunt | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | Flucloxacillin (IV) | Vancomycin (IT) | |||

| Gram negative bacilli | Meropenem (IV) | Ceftriaxone (IV | Dependent on clinical response and CSF | ||

| Enterococcus spp. | Linezolid | Dependent on clinical response and CSF | |||

| VP/VA shunt | Coagulase negative Staphylococci | Vancomycin (IV) | Rifampicin (oral) | Time for device in situ, sterile CSF before new EVD/shunt | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Flucloxacillin (IV) | Vancomycin (IV) | Rifampicin (oral) | ||

| Gram negative bacilli | Meropenem (IV) | 14 days | |||

| Antimicrobial choice is monotherapy, with a choice between antimicrobial (a) and (b). Exception is rifampicin for S. aureus. related VP shunt infection | |||||

Meropenem can be used empirically in accordance with the IDSA guidelines, but empirical linezolid is not recommended. In order to account for empirical use of meropenem, we calculated the duration of inappropriate treatment from the date at which cultures grew the causative organism to the time when meropenem was stopped. The actual treatment regimen (number of doses/day) was not collected, so it was estimated that all patients would be given the recommended three times-a-day (meropenem) or twice-a-day (linezolid). Finally, costings for each drug based on those detailed in the online version of British National Formulary [29] and this was used to calculate the total cost of inappropriate use of meropenem and linezolid.

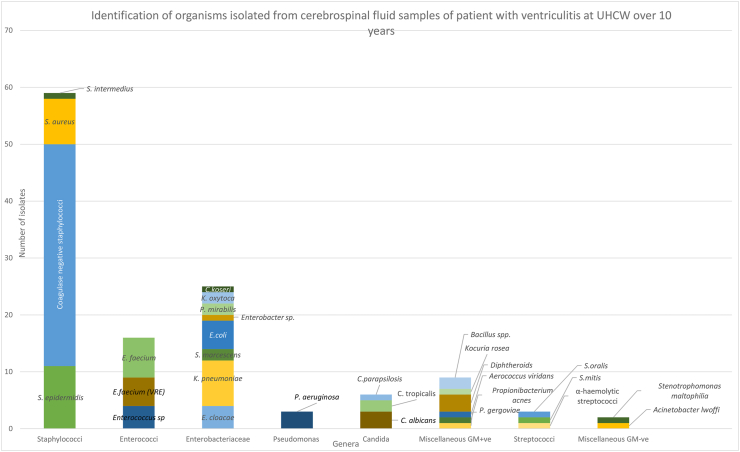

To aid the clarity of results, the organisms were grouped into genera, Enterobacteriaceae family or miscellaneous Gram-positive or Gram-negative organisms where there was only one isolate from a family or genus. These results were then displayed graphically with full identification to species level where this was available. Antimicrobial choice was then compared with culture results to determine if its use was in accordance with guidelines.

Results

There were 99 patients with confirmed ventriculitis and the treatment administered in these cases was examined. The exclusion criteria are detailed in Figure 1.

Descriptive statistics for studied population

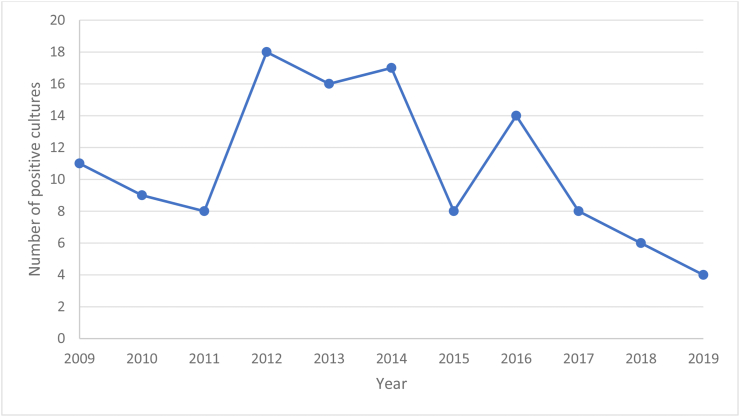

Of the 99 patient records examined, 43% of the positive cultures occurred between 2012 and 2014 (Figure 2). EVDs and VP shunts were associated with most cases (73% and 18% respectively). The remainder were either other device-related infections or CSF leaks, which were included due to clinicians having documented “ventriculitis” or “healthcare-associated meningitis” during the treatment period (Table IV). Some patients had multiple devices inserted due to the replacement of an infected device and subsequent reinfection. In order to minimise amount of patient identifiable information, the indication for these devices or any other demographic data were not recorded.

Figure 2.

Number of single positive cultures of ventriculitis per year which is used as a proxy to determine the number of cases of ventriculitis per year.

Table IV.

Clinical background of ventriculitis cases

| Clinical background | Number of devices | Percentage of ventriculitis cases (%) |

|---|---|---|

| EVD | 76 | 73 |

| VP shunt | 21 | 20 |

| Post neurological surgery | 1 | 1 |

| CSF leak | 3 | 3 |

| Lumbar drain | 3 | 3 |

| Metal work in-situ | 2 | 2 |

| Graft infection | 1 | 1 |

Comparison of antimicrobial treatment administered and costing

Of the 105-total number of device-related ventriculitis (CSF leak was not included), 95% were removed. There were several cases of ventriculitis which had multiple devices in situ. There was a large amount of variation in the timeframe for removal with an average time of 10 days (Standard deviation (SD) 13.95), with a range of -4 days–67 days (some devices were removed prior to cultures becoming positive). For antimicrobial selection, 56% received antimicrobial therapy which matched the IDSA guidelines and 50% received antimicrobial therapy which matched the UHCW guidelines. There were large amounts of variation in the length of treatment, with average length of antimicrobial treatment of 19 days (SD 17.56) (Table V), with a range of -6 to 67 days (1 case had a further positive culture which occurred after antimicrobials were stopped). IT antimicrobials were given to 55 patients, of which 49% of these had documentation for method of administration recommended by the guidelines. Fungal isolates were all treated in accordance with IDSA guidelines for antifungal agents and these guidelines provide no recommended duration of treatment regime. UHCW does not provide guidelines on the management of fungal ventriculitis as such cases are managed by microbiologists on a case by case basis.

Table V.

Number of cases of ventriculitis managed in accordance with IDSA and UCHW guidelines

| Treatment recommended | Number receiving treatment (%) | Average length of treatment was received (days), with STD in parentheses. |

|---|---|---|

| Medical device removal | 99 (94) | 10.25 (13.95) |

| IDSA antimicrobial selection | 57 (56) | 19 (17.56) |

| UHCW antimicrobial selection | 50 (50) |

Average length of treatment with standard deviation in parentheses was also calculated, with antimicrobial representing the average length of treatment.

Only eight cases of ventriculitis had a treatment duration matching the guideline recommendation (Table VI). Approximately half of cases were under the recommended duration and half exceeded the recommended length.

Table VI.

Number of cases of ventriculitis which matched treatment length recommended by the guidelines

| Duration of treatment | Number of bacterial infections treated |

|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | |

| Treatment length less than recommendation by guidelines | 29 |

| Recommended treatment duration | 8 |

| Treatment length greater than recommendation by guidelines | 37 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | |

| Treatment length less than recommendation by guidelines | 10 |

| Recommended treatment duration | 0 |

| Treatment length greater than recommendation by guidelines | 10 |

For Gram-positive infections, the recommended duration of treatment is 10–14 days. For Gram-negative infections, the recommended treatment duration is 10–14 days, some experts suggest treatment for 21 days, [4].

The most commonly misused antimicrobials not recommended by either IDSA or UHCW guidelines were meropenem and linezolid (Table VII). Meropenem was used for Gram positive organisms in 36 cases. Linezolid was inappropriately used in 9 cases where a coagulase negative staphylococcus was isolated (Table VIII). The cost of misused meropenem and linezolid was estimated to be £42,752 and £158,420 respectively, over the 10 years of this study. This equates to approximately £20,117 per annum spent on inappropriate antimicrobial use in the management of ventriculitis at UHCW.

Table VII.

Estimate of costing of the inappropriate use of meropenem and linezolid during 2009–2019

| Antimicrobial | Total duration of inappropriate use (days) | Estimated inappropriate doses | Cost (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meropenem | 835 | 2505 | 42,752.34 |

| Linezolid | 178 | 356 | 158,420 |

Table VIII.

Number of cases where antimicrobial choice was inappropriate with rationale as to why this was considered inappropriate

| Antimicrobial | Number of cases used | Number of cases with inappropriate use | Rationale for inappropriate use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meropenem | 41 | 36 | Use for Gram-positive organism |

| Linezolid | 22 | 9 | Use in coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| Vancomycin IV | 36 | 1 | Use for Gram-negative organism |

| Vancomycin IT | 46 | 1 | Use for Gram-negative organism |

Outcome of ventriculitis

The average time for cultures to become negative also showed significant variation, with an average of 8 days (SD 10.99), with a range of 0–70 days. However, several cases lacked adequate follow up cultures so this value may not be representative. CSF WCC, protein, and glucose showed no correlation to infection resolution and were not used to determine treatment outcome. Mortality rate was 14% of cases of confirmed ventriculitis over the 10-year period.

Causative organisms of ventriculitis at UHCW

123 organisms were identified from 99 cases, with multiple isolates being identified in 19 cases. The clinical significance of all the isolates was occasionally difficult to ascertain, owing to variable documentation. Aseptic technique was documented in 53% of positive CSF samples. The most common organisms identified were coagulase-negative staphylococci. Of these, 12 were identified to species level with Staphylococcus epidermidis being the most common (11). Enterobacteriaceae were the most common Gram-negative organisms identified, with Klebsiella pneumoniae being the most common species identified. Candida species were the only fungal causes and were identified in 6 cases. C. albicans was the most frequently identified species (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Identification of micro-organisms isolated from CSF samples of ventriculitis cases. Full names of identified organisms are as follows: VRE=Vancomycin Resistant enterococci, Citrobacter koseri, Klebsiella oxytoca, Proteus miirabilis, Escherichia.

Discussion

IDSA guidelines state that CSF shunt or drain-related ventriculitis should be managed by the removal of such devices [4] combined with targeted antimicrobials. Antimicrobial treatment alone has a low probability of success [30], or high risk of recurrence [31]. A common feature of device-related infections is adherence and biofilm formation, which are difficult to treat with antimicrobials alone due to the immune evasion and intrinsic tolerance to antimicrobials [32] and therefore, antimicrobials alone are not recommended for ventriculitis management. Most cases did have device removal at UCHW but there was significant variation in when devices were removed. The reason for this was difficult to ascertain, owing to variation in documentation. When intracranial devices should be removed is controversial because there is little consensus on timing of removal and the risk of recurrence being higher if devices remain in-situ [30,33]. This suggests several different approaches for when devices should be removed, and documentation for a rationale is lacking. According to UHCW policy, documentation should be accessible via the “Theatre” tab of CRRS but for several cases this was either not present or inferred from other sources.

Meropenem is useful for the treatment of ventriculitis, due to good CSF penetration and broad spectrum of activity [34]. Empirical meropenem is recommended by the IDSA. Meropenem is only recommended for the treatment Gram-negative organisms and is not for the management of Staphylococci or Enterococcal infections [35,36]. Although meropenem is effective for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections which are methicillin-sensitive, it has little or no activity against most other staphylococci [37,38]. Furthermore, the continued use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials when not required is a concern for antimicrobial stewardship. Treatment with unnecessary or inappropriate antimicrobials increases the risk of antimicrobial resistance development [39] and risk of Clostridioides difficile infection [40]. In addition, the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae has been declared a significant threat by the CDC [41] and Public Health England (now UK Health Security Agency) [42]. The rationalisation of antimicrobial therapy is a vital component of infection management and documentation was lacking in many of the cases examined.

This study also demonstrates the potential financial costs of inappropriate antimicrobial use. For serious and challenging infections such as ventriculitis, it may be understandable to continue empirical antimicrobials despite microbiological evidence. Studies have shown that this is a common, complex and multi-factorial phenomenon [43,44]. Further investigation of these factors is outside the scope of this study. Our recommendations to improve antimicrobial use are education and feedback of these results to all members of the multidisciplinary team to promote discussion to identify interventions to improve the antimicrobial treatment of ventriculitis in the future. Such an approach is a cornerstone of antimicrobial stewardship and there is evidence to support its effectiveness [45,46]. Further studies are needed to monitor any improvement in the management of ventriculitis in UHCW. The comparative rarity of confirmed ventriculitis in UHCW means that a long period of time is required for enough ventriculitis cases to have occurred to reach significance.

The duration of antimicrobial therapy was highly variable in this study. Although the IDSA guidelines give recommendations for the optimal treatment duration, these are based on evidence from poor quality cohort studies, observational studies and expert opinion. Treatment duration should be based on clinical response and CSF results [47]. However, CSF culture results are directly affected by the administration of antimicrobials prior to CSF sample collection [48] and the CSF WCC can vary significantly [49]. Therefore, due to variations in documentation and poor reliability of using CSF parameters to predict resolution of infection it is difficult to determine the optimum antimicrobial treatment duration. There was poor documentation for the rationale of treatment duration used or why treatment was stopped. The mortality rate seen in this study is representative of rates from other studies [[50], [51], [52]].

Poor documentation affected every aspect of our data collection. Where treatment deviated from guidelines, there was a lack of explanation in documented in paper notes. Poor documentation of aseptic technique of CSF sampling and method of IT antimicrobial administration may have affected the results of this study. Although we are confident our results reflect the reality of treatment of ventriculitis, poor documentation adds a degree of uncertainty. Often, an indication for antimicrobials was not documented and was identified by methods described. What is more, where multiple isolates were identified it was unclear which were considered significant. Furthermore, was difficult to ascertain the decision making which led to deviation from both sets of guidelines due to the retrospective nature of this work and variable thoroughness of documentation. Inadequate documentation for medication changes has been shown by studies in different clinical areas [53,54]. Further research is needed to determine the root cause for the absence of detailed documentation. However, restraint should be exercised before simply recommending more documentation as this alone is unlikely to lead to significant change in patient outcomes because it reduces time for direct patient care [55,56]. Currently, there is a multi-disciplinary approach to the management of ventriculitis, with microbiologist advice but with ultimate clinical responsibility with the neurosurgical team.

The results of isolated organisms are reflected in other studies with staphylococci being the most frequent [12,49,57]. Enterococci were the second most common isolate, which is unusual compared to other studies [12,58]. Enterococcal CSF infections are often polymicrobial [59]. It is possible that the empirical use of vancomycin may have selected a single enterococcal strain and several vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolates were reported. The recent trend in some centres of increased Gram-negative isolates, especially Acinetobacter baumannii was not observed in this neurosurgical centre [60,61]. The clinical significance of some of the organisms grown in this study is not clear. Although isolates were excluded if documented as not clinically significant, the retrospective nature of this study means it is likely some organisms included were not clinically significant.

This study has several limitations. The initial search may have excluded some cases. Although ventriculitis should be treated on the neurosurgical ward at UHCW, it is possible some cases may have been treated elsewhere. So-called outliers (patients who are receiving specialist medical or surgical care in locations other than their specialist ward) are frequent, with one study reporting just under 10% of patients receive care as outliers [62]. Many patients in this study receiving some care on ICU, so it is possible cases would have been missed if ventriculitis occurred whilst on ICU and the patient died before ICU discharge. It is also possible that excluding CSF samples with organisms classically causing acute meningitis, may have excluded cases of ventriculitis. There are several case reports of ventriculitis caused by such organisms [63,64]. The rarity of such cases is unlikely to have a significant impact on the quality of our findings.

Another potential limitation is the clustering of cases between 2012 and 2014. As the both the IDSA and UHCW guidelines were published in 2017, the evidence guiding the management prior to this may have differed in recommendations. However, many studies published pre-2017 show similar treatment recommendations [5,35,65]. The costing data may also have been affected by this clustering of cases. We used an estimate for treatment regimes in this study and used current pricing for meropenem and linezolid used in cases treated over 10 years. As medication prices vary over time [66], this value is an estimate only and the true figure will differ. In addition to this, dosing was assumed to be that of normal renal function and no data was collected about patient's renal function. Therefore, this would also overestimate cost if patients had reduced frequency or dose of antimicrobial depending on their renal function [29]. Furthermore, this study only analysed cases at one centre and therefore how relatable these findings are to other sites is difficult to comment on. However, inappropriate antimicrobial use is well-recognised in healthcare.

To the best of our knowledge there are no other published studies on the local management of all cases of confirmed ventriculitis. In addition, the data presented here further supports the importance of antimicrobial stewardship. The data on the causative organisms identified in the study may help support future empirical management of ventriculitis at UHCW.

We suggest that further studies should be conducted about the management of suspected or culture-negative ventriculitis. In addition, research into the root cause of poor documentation observed in this study should be conducted. Future research may also investigate the possible causes for the current trend in decline in cases. One potential cause of this may be improved neurosurgical technique, which several studies have shown to reduce incidence of ventriculitis [67,68].

Conclusions

This study provides detailed analysis of the management of confirmed ventriculitis cases at UHCW including the pattern of causative organisms. The study highlighted the importance of antimicrobial stewardship and the potential financial implications of inappropriate antimicrobial use.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my project supervisor for all their support and guidance offered throughout the course of this study. I would also like to thank the administrative staff in the pathology department for their help with requesting patient notes and the Microbiology IT department for performing the initial search. Finally, I would like to thank my partner for all her support.

Author statement

Dr Peter Munthali conceptualised the project, supervised and edited the manuscript

Dr Daniel Lilley undertook the research, analysis and writing of the manuscript

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

No competing interests are present from the authors of this work.

References

- 1.Kourbeti I.S., Vakis A.F., Ziakas P., Karabetsos D., Potolidis E., Christou S., et al. Infections in patients undergoing craniotomy: risk factors associated with post-craniotomy meningitis. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:1113–1119. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.JNS132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin C., Zhao X., Sun H. Analysis on the risk factors of intracranial infection secondary to traumatic brain injury. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18:81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozier A.P., Sciacca R.R., Romagnoli M.F., Connolly E.S., Jr. Ventriculostomy-related infections: a critical review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:170–181. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200207000-00024. ; discussion 81-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tunkel A.R., Hasbun R., Bhimraj A., Byers K., Kaplan S., Scheld M., et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Healthcare-Associated Ventriculitis and Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:e34. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphreys H. Jenks PJ Surveillance and management of ventriculitis following neurosurgery. J Hosp Infect. 2015;89:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire. https://www.uhcw.nhs.uk/our-services-and-people/our-departments/neurosciences/. Date accessed:20/01/2021.

- 7.Phan K., Schultz K., Huang C., Halcrow S., Fuller J., McDowell D., et al. External ventricular drain infections at the Canberra Hospital: A retrospective study. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;32:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patwardhan R.V. Nanda A Implanted ventricular shunts in the United States: the billion-dollar-a-year cost of hydrocephalus treatment. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:139–145. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000146206.40375.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hariri O., Farr S., Lawandy S., Zampella B., Miulli D. Siddiqi J Will clinical parameters reliably predict external ventricular drain-associated ventriculitis: Is frequent routine cerebrospinal fluid surveillance necessary? Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:137. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_449_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey S., Li L., Deng X.Y., Cui D.M., Gao L. Outcome Following the Treatment of Ventriculitis Caused by Multi/Extensive Drug Resistance Gram Negative Bacilli; Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumonia. Front Neurol. 2019;9:1174. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portillo M.E., Corvec S., Borens O. Trampuz A Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated pathogen in implant-associated infections. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/804391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srihawan C., Habib O., Salazar L. Hasbun R Healthcare-Associated Meningitis or Ventriculitis in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2646–2650. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cicek-Senturk G., Ozay R., Kul G., Altay F., Kuzi S., Gurbuz Y., et al. Evaluation of Postoperative Meningitis: Comparison of Meningitis Caused by Acinetobacter spp. and Other Meningitis. Turk Neurosurg. 2018 doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.25151-18.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shang F., Xu Y., Wang N., Cheng W., Chen W., Duan W. Diagnosis and treatment of severe neurosurgical patients with pyogenic ventriculitis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Neurol Sci. 2018;39:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-3146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munthali P., Li M. Neurosurgical antimicrobial guidelines 3edn. Microbiology, University Hopsital Coventry and Warwickshire. Clifford Bridge Rd, Coventry, CV2. 2017;2DX:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell B.G., Schellevis F., Stobberingh E., Goossens H., Pringle M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antimicrobial consumption on antimicrobial resistance. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies S.C. ume Two. Department of Health; London: 2013. Annual report of the chief medical office. (Infections and rise of antimicrobial resistance). 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyar O.J., Huttner B., Schouten J., Pulcini C. What is antimicrobial stewardship? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:793–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahu M.K., Siddharth B., Choudhury A., Vishnubhatla S., Singh S., Menon R., et al. Incidence, microbiological profile of nosocomial infections, and their antimicrobial resistance patterns in a high volume Cardiac Surgical Intensive Care Unit. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19:281–287. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.179625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu X., Tong A., Wang D., Sun H., Chen L. Dong M Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Gram-negative and Gram-positive strains isolated from inpatients with nosocomial infections in a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China from 2011 to 2014. J Chemother. 2017;29:317–320. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2016.1157946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blomberg B., Mwakagile D.S., Urassa W.K., Maselle S.Y., Mashurano M., Digranes A., et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Publ Health. 2004;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L., Huang Y., Zhou Y., Buckley T. Wang HH Antimicrobial administration routes significantly influence the levels of antimicrobial resistance in gut microbiota. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3659–3666. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00670-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaac S., Scher J.U., Djukovic A., Jimenez N., Littman D., Abramson S., et al. Short- and long-term effects of oral vancomycin on the human intestinal microbiota. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:128–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theriot C.M. Young VB Interactions Between the Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Clostridium difficile. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:445–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez J.L. General principles of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2014;11:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lwin S., Low S.W., Choy D.K., Yeo T.T. Chou N External ventricular drain infections: successful implementation of strategies to reduce infection rate. Singap Med J. 2012;53:255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sam J.E., Lim C.L., Sharda P., Wahab N.A. The Organisms and Factors Affecting Outcomes of External Ventricular Drainage Catheter-Related Ventriculitis: A Penang Experience. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018;13:250–257. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_150_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albano S., Berman B., Fischberg G., Siddiqi J., Bolin Y., Khan Y., et al. Retrospective Analysis of Ventriculitis in External Ventricular Drains. Neurology research international. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/5179356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Committee JF http://www.medicinescomplete.com British National Formulary (online, accessed 16/2/2020) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press.

- 30.Schreffler R.T., Schreffler A.J., Wittler R.R. Treatment of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections: a decision analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:632–636. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James H.E., Walsh J.W., Wilson H.D., Connor J.D. The management of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections: a clinical experience. Acta Neurochir. 1981;59:157–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01406345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryers JD Medical biofilms Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;100:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bit.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kestle J.R., Garton H.J., Whitehead W.E., Drake J.M., Kulkarni A.V., Cochrane D.D., et al. Management of shunt infections: a multicenter pilot study. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:177–181. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Beek D., Drake J.M., Tunkel A.R. Nosocomial bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:146–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown JdLRBPDLIKPEM The management of neurosurgical patients with postoperative bacterial or aseptic meningitis or external ventricular drain-associated ventriculitis. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:7–12. doi: 10.1080/02688690042834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lich B.F., Conner A.K., Burks J.D., Glenn C.A., Sughrue M.E. Intrathecal/Intraventricular Linezolid in Multidrug-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis Ventriculitis. J Neurol Surg Rep Germany. 2016:e160–e161. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White R.L., Friedrich L.V., Manduru M., Mihm L.B. Bosso JA Comparative in vitro pharmacodynamics of imipenem and meropenem against ATCC strains of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Bacteroides fragilis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;39:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(00)00219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhanel G.G., Wiebe R., Dilay L., Thomson K., Rubinstein E., Hoban D.J., et al. Comparative review of the carbapenems. Drugs. 2007;67:1027–1052. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baur D., Gladstone B.P., Burkert F., Carrara E., Foschi F., Dobele S., et al. Effect of antimicrobial stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hensgens M.P., Goorhuis A., Dekkers O.M. Kuijper EJ Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antimicrobials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:742–748. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and P . 2013. Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Retrieved July 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crosford P., Keogh B. In: Wellington house, 133-155 waterloo road. England P.H., editor. 2014. Re: Addressing the infection risk from carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and other carbapenem-resistant organisms. London SE1 8UG. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skodvin B., Aase K., Brekken A.L., Charani E., Lindemann P.C. Smith I Addressing the key communication barriers between microbiology laboratories and clinical units: a qualitative study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2666–2672. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sedrak A., Anpalahan M., Luetsch K. Enablers and barriers to the use of antimicrobial guidelines in the assessment and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia-A qualitative study of clinicians' perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan A Antimicrobial stewardship Why we must, how we can. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:673–679. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84gr.17003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davey P., Marwick C.A., Scott C.L., Charani E., McNeil K., Brown E., et al. Interventions to improve antimicrobial prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alnimr A.A. Protocol for Diagnosis and Management of Cerebrospinal Shunt Infections and other Infectious Conditions in Neurosurgical Practice. BCN. 2012;3:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nigrovic L.E., Malley R., Macias C.G., Kanegaye J.T., Moro-Sutherland D.M., Schremmer R.D., et al. Effect of antimicrobial pretreatment on cerebrospinal fluid profiles of children with bacterial meningitis. Pediatrics. 2008;122:726–730. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conen A., Walti L.N., Merlo A., Fluckiger U., Battegay M. Trampuz A Characteristics and treatment outcome of cerebrospinal fluid shunt-associated infections in adults: a retrospective analysis over an 11-year period. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:73–82. doi: 10.1086/588298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bari M.E., Haider G., Malik K., Waqas M., Mahmood S.F. Siddiqui M Outcomes of post-neurosurgical ventriculostomy-associated infections. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:124. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_440_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar R., Singhi P., Dekate P., Singh M., Singhi S. Meningitis related ventriculitis--experience from a tertiary care centre in northern India. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82:315–320. doi: 10.1007/s12098-014-1409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Busl KM Healthcare-Associated Infections in the Neurocritical Care Unit. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19:76. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0987-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peusschers E., Twine J., Wheeler A., Moudgil V., Patterson S. Documentation of medication changes in inpatient clinical notes: an audit to support quality improvement. Australas Psychiatr. 2015;23:142–146. doi: 10.1177/1039856214568215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nelson E., Falls Reynolds P Inpatient. Improving assessment, documentation, and management. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u208575.w3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joukes E., Abu-Hanna A., Cornet R., de Keizer NF Time Spent on Dedicated Patient Care and Documentation Tasks Before and After the Introduction of a Structured and Standardized Electronic Health Record. Appl Clin Inf. 2018;9:46–53. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1615747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baumann L.A., Baker J., Elshaug A.G. The impact of electronic health record systems on clinical documentation times: A systematic review. Health Pol. 2018;122:827–836. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weisfelt M., van de Beek D., Spanjaard L., de Gans J. Nosocomial bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective series of 50 cases. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pintado V., Cabellos C., Moreno S., Meseguer M.A., Ayats J., Meningitis Viladrich PF Enterococcal. A Clinical Study of 39 Cases and Review of the Literature. Medicine. 2003;82 doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000090402.56130.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang W.N., Lu C.H., Huang C.R., Chuang Y.C. Mixed infection in adult bacterial meningitis. Infection. 2000;28:8–12. doi: 10.1007/s150100050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen F., Deng X., Wang Z., Wang L., Wang K., Gao L. Treatment of severe ventriculitis caused by extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by intraventricular lavage and administration of colistin. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:241–247. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S186646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Senturk G.C., Ozay R., Kul G., Altay F.A., Kuzi S., Gurbuz Y., et al. Evaluation of post-operative meningitis: comparison of meningitis caused by Acinetobacter spp. and other possible causes. Turk Neurosurg. 2019;29(6):804–810. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.25151-18.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stylianou N., Fackrell R., Vasilakis C. Are medical outliers associated with worse patient outcomes? A retrospective study within a regional NHS hospital using routine data. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van den Heuvel N., O'Leary C. Gwee A Meningococcal Meningitis Complicated by Ventriculitis in an Infant. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54:213–214. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ben Shimol S., Einhorn M., Greenberg D. Listeria meningitis and ventriculitis in an immunocompetent child: case report and literature review. Infection. 2012;40:207–211. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beer R., Lackner P., Pfausler B. Schmutzhard E Nosocomial ventriculitis and meningitis in neurocritical care patients. J Neurol. 2008;255:1617–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alpern J.D., Zhang L., Stauffer W.M. Kesselheim AS Trends in Pricing and Generic Competition Within the Oral Antimicrobial Drug Market in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1848–1852. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kulkarni A.V., Drake J.M., Lamberti-Pasculli M. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection: a prospective study of risk factors. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:195–201. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.2.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tulipan N. Cleves MA Effect of an intraoperative double-gloving strategy on the incidence of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2006;104:5–8. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.104.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]