Abstract

Objective:

This qualitative study explored the impact of postoperative complications on surgeons and their well-being.

Background:

Complications are an inherent component of surgical practice. Although there have been extensive efforts to reduce postoperative complications, the impact of complications on surgeons have not been well-studied. Surgeons are often left to process their own emotional responses to these complications, the effects of which are not well characterized.

Methods:

We conducted 46 semi-structured interviews with a diverse range of surgeons practicing across Michigan to explore their responses to postoperative complications and the effect on overall well-being. The data were analyzed iteratively, through steps informed by thematic analysis.

Results:

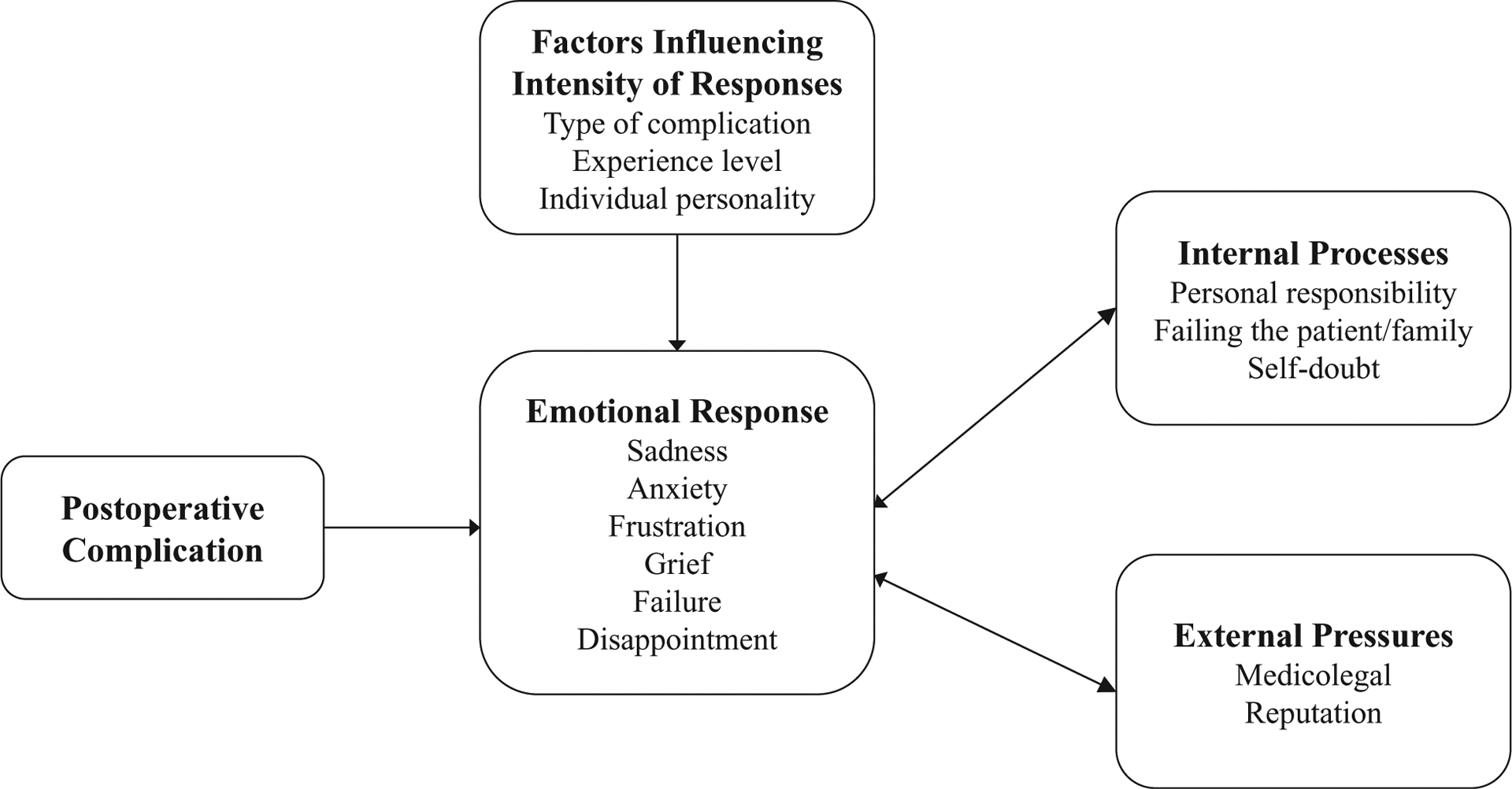

Participants described feelings of sadness, anxiety, frustration, grief, failure, and disappointment after postoperative complications. When asked to elaborate on these responses, participants described internal processes such as feelings of personal responsibility and failure, self-doubt, and failing the patient and family. Participants also described external pressures influencing the responses, which included potential impact to reputation and medicolegal issues. Experience level, type of complication, and the surgeon’s individual personality were specific factors that influenced the intensity of these responses.

Conclusion:

Surgeons’ emotional responses after postoperative complications may negatively impact individual well-being, and may represent a threat to the profession altogether if these issues remain inadequately recognized and addressed. Knowledge of the impact of unwanted or unexpected outcomes on surgeons is critical in developing and implementing strategies to cope with the challenges frequently encountered in the surgical profession.

Keywords: emotional response, postoperative complications, surgeon wellness

Postoperative complications are an inherent component of surgical practice and are only expected to increase as the complexity of medical care continues to grow.1 Although there have been extensive efforts to reduce postoperative complications, their impact on surgeons have not been well-studied. Surgeons are often left to process their own emotional responses to these complications, the effects of which are not well characterized.

The profound impact that errors and adverse events play on patients have been previously studied, yet surgical outcomes research often fails to consider an important stakeholder: the surgeon. In addition, a breadth of literature focusing on wellness among surgeons exists, yet much of this work is limited to systemic causes, such as excessive admin tasks, long hours, increasing call burdens, lack of autonomy, and patient volume.3,4 Although these factors undoubtedly impact surgeon wellness, far fewer studies have explored the role that dealing with a postoperative complication or death can play on overall surgeon well-being.5,6 Further, the scholarship that does exist are limited to medical providers as a whole or trainees, rather than concentrating on practicing surgeons.7–10 The few studies that have focused on aspects of emotional responses after adverse events among surgeons are primarily survey-based, leaving much to be understood in how individuals experience these events.1,2,11

In this context, we sought to explore the impact of postoperative complications on surgeons and their well-being. To do this, we employed an exploratory qualitative design to conduct semi-structured interviews among a diverse range of surgeons practicing across the state of Michigan. We specifically inquired about their emotional responses to poor or unwanted outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design

This report represents part of a larger exploratory, qualitative study designed to gain a comprehensive understanding of how surgeons make decisions about high-risk surgery. High-risk was defined as high probability of either postsurgical death (ie, inpatient mortality of at least 1%) or poor outcomes (eg, unexpected intensive care unit admission, prolonged hospital stay, unexpected non-home discharge disposition).12–14 The findings in this manuscript focus only on the portion of the interview regarding personal responses to an unexpected postoperative outcome or complication.

Interview Participants

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants by email through the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, the Michigan Chapter of the American College of Surgeons, and Michigan Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Participants were eligible if they were an actively practicing surgeon in the state of Michigan. Forty-six surgeons from community, tertiary-care, and academic sites agreed to participate in this study. Surgeons were diverse with respect to age, sex, year in practice, type of practice, and surgical subspecialty. Participants were monetarily compensated for their participation in the interviews.

Interview Procedures

All participants were provided with a written or oral informed consent statement and verbally consented before their interview. Individual interviews were conducted in-person or over the phone between October 2018 and April 2019 by 2 research analysts (CAV and MEB), who have expertise in qualitative interviewing, and the senior author (PAS), a surgeon and health services researcher. Two members of the research team (PAS and CAV) designed an exploratory interview topic guide to explore high-risk decision-making for older adult (>65) patients. Participants were asked to walk the interviewer through the steps they would take in making decisions about high-risk surgery. Participants were further prompted to consider: (1) the role of patient cognitive and functional outcomes; (2) the role of postoperative complications; (3) barriers and facilitators to palliative care; and (4) their personal response after an unexpected postoperative outcome or complication. Several iterations of the interview guide were generated and piloted for content validity, presentation, and clarity of information. All data, including that collected during pilot interviews, were included in the final data analysis. All interviews were digitally-recorded and lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Transcripts were not returned to participants for review.

Analysis

The data were analyzed iteratively, through steps informed by thematic analysis.15 All members of the research team independently read through transcripts to identify an initial set of codes. The team then met to discuss the codes and map them to a coding schema, creating a codebook based on overarching domains. Due to the exploratory nature of the interview instrument, the initial coding process was intentionally kept broad two members of the research team (CAV and ADR) independently coded the transcripts, meeting regularly to discuss discrepancies and to modify the codebook when necessary. From there, each domain was assigned to a research member based on research interest. A more detailed codebook was created under each domain, a process that was done iteratively with involvement from the entire research team. Transcribed interviews were coded in MAXQDA (version 18.2.3), a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software.

This study was deemed exempt by the University of Michigan Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRBMED HUM00157651).

RESULTS

A total of 46 surgeons participated in semi-structured interviews. The majority of participants were male (n = 38, 82.6%), non-Hispanic white (n = 36, 78.3%), and specialized in general (n = 19, 41.3%) or colorectal (n = 14, 30.4%) surgery. The mean number of years of experience in their current clinical position was 14 (range 1–30) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Professional Characteristics

| Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 25–34 | 1 | 2% |

| 35–44 | 18 | 39% |

| 45–54 | 16 | 35% |

| 55–64 | 9 | 20% |

| 65–74 | 1 | 2% |

| No response | 1 | 2% |

| Sex | ||

| Man | 38 | 83% |

| Woman | 8 | 17% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 36 | 75% |

| Asian | 10 | 25% |

| Years in practice | ||

| 0–5 | 8 | 17% |

| 6–10 | 13 | 29% |

| 11–15 | 8 | 17% |

| 16–20 | 6 | 13% |

| 20+ | 11 | 24% |

| Type of hospital | ||

| Academic | 27 | 59% |

| Community | 15 | 33% |

| Other | 4 | 8% |

| Specialty* | ||

| General | 19 | 41% |

| Colorectal | 14 | 30% |

| Kidney and liver | 1 | 2% |

| Vascular | 5 | 10% |

| Endocrine | 2 | 4% |

| Surgical critical care/acute care | 8 | 17% |

| Trauma | 4 | 8% |

| Child thoracic | 1 | 2% |

| Oncology | 4 | 8% |

| Plastic | 1 | 2% |

| % Emergent | ||

| 0%−10% | 23 | 50% |

| 11%−20% | 9 | 20% |

| 21%−30% | 4 | 9% |

| 31%−40% | 1 | 2% |

| 41%−50% | 1 | 2% |

| 51%−60% | 0 | 0% |

| 61%−70% | 1 | 2% |

| 71%−80% | 3 | 7% |

| 81%−90% | 1 | 2% |

| 91%−100% | 1 | 2% |

| No response | 2 | 4% |

| % Older adults | ||

| 21%−30% | 2 | 4% |

| 31%−40% | 12 | 26% |

| 41%−50% | 13 | 29% |

| 51%−60% | 4 | 9% |

| 61%−70% | 4 | 9% |

| 71%−80% | 8 | 17% |

| 81%−90% | 0 | 0% |

| 91%−100% | 1 | 2% |

| No response | 2 | 4% |

Specialty overlap; values do not total n = 46 or 100%.

Emotional Response to Postoperative Complications

Participants described their responses to postoperative complications in a variety of ways, including feelings of sadness, anxiety, frustration, grief, failure, and disappointment (Table 2).“You feel depressed. In cases of a patient dying, you’re saddened by it. It’s kind of at the back of your mind for days, for weeks, sometimes longer. It takes a very deep emotional toll.” (ID 31)

TABLE 2.

Description of Feelings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although describing these emotional responses, participants reflected on the internal processes and external pressures driving these feelings, and on the factors impacting the intensity of these emotions. Several of these domains often overlapped, with participants rarely able to identify a single cause (Tables 3 and 4).

TABLE 3.

Source of Feelings (Internal Processes)

| Personal responsibility |

|

| |

| |

| Failing the patient/family |

|

| |

| Self-doubt |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

TABLE 4.

Source of Feelings (External Pressures)

| Medicolegal |

|

| |

| |

| Reputation |

|

| |

| |

|

Internal Processes

When asked to elaborate on the source of emotional responses, participants most often described how sentiments were rooted in feelings of personal responsibility and failure, self-doubt, and failing the patient and family (Table 3).

Personal Responsibility

A common response was feeling personally responsible for any and all outcomes. Some participants described how surgeons have the greatest amount of responsibility – compared to physicians from other specialties – and consequently, greater accountability for postoperative complications. Participants described their process of self-reflection, often battling between assigning personal blame and acknowledging the inevitability of experiencing an unwanted or unexpected outcome. Despite participants recognizing that certain outcomes resulted from factors beyond the surgeon’s control, many still experienced feeling some level of burden after postoperative complications.

“I think the, there’s a, you know, real sense of personal involvement in the outcomes that patients have, those, the clinical outcomes and their functional outcomes because of the way, because of the specific relationship of surgery.”

(ID 7)

Failing the Patient/Family

Several participants described the responsibility they felt to “do the right thing,” and how complications sometimes challenged that responsibility, making them feel like they failed to meet the expectations of the patient and/or patient’s family. For some participants, the depth of the surgeon-patient/family relationship influenced this feeling, with responses deepening as the bond with the patient and/or family was more established, either through length of relationship or through intensity of experience.

“I certainly feel like, you know, families trusted you to do this, and even though it may not be your fault, it may not be a technical issue, but they certainly have entrusted you, and I do feel a certain sort of failure in that regard, like I totally blew it for you.”

(ID 8)

Self-doubt

Participants expressed feeling varying levels of self-doubt (referring here to one’s doubt or uncertainty in one’s abilities or actions), describing how since surgeons typically consider their technical and judgement skills to be proficient, complications challenged that confidence. For some, this self-doubt was directly in reference to the complication, with participants wondering what they could have done differently to prevent the unfavorable outcome. For others, self-doubt led them to question if they chose the right specialty or in some cases, if they should be practicing surgery at all.

“Complications is still what makes this job most difficult. Makes you think every once in a while, geez, I should have gone into… radiology or pathology.”

(ID 10)

In addition to describing feelings of self-doubt, some participants reported anticipating potential sources of complications and preparing meticulously to preemptively avoid complications, thereby mitigating the emotional response.

“They could still have a problem. But I did all the things I could do to kind of convince myself that, as I was leaving that operating room, everything was okay. So then I, you know, yeah, I would say I try to anticipate, solve, avoid problems.”

(ID 42)

External Pressures

In addition to describing internal processes, participants also often described external pressures influencing their emotional responses, including fear of medicolegal consequences and negative impact to reputation (Table 4).

Medicolegal

Participants asserted fearing potential medicolegal consequences. Participants described having this concern both in instances of postoperative complications and in instances of not offering surgical interventions, resulting in the patient or family pursuing legal action. For some, these situations were described as being more common when families were not physically present or not initially involved in conversations about treatment. Participants also described how the fear of potential medicolegal issues influenced what they were willing to discuss with both colleagues and patients. Others reflected on how the fear of potential medicolegal consequences encouraged them to be more mindful of documentation processes. “And then there, you can be sued. You can actually be sued. So, there’s all these things which, you know, interface. And obviously, the worst thing is to be sued and be told that you ruined somebody’s life, and you probably did.” (ID 23)

Reputation

Participants expressed concern for complications potentially impacting their professional reputation, both at their home institution and within the community. At an institutional level, participants described the competitive nature of surgical departments, describing how surgeons are often hypercritical of mistakes made by their colleagues. For some, this contributed to an unsupportive environment where surgeons felt attacked, promoting a need to defend their value to the hospital administration and their peers. At the community level, participants described how being known for poor quality outcomes could affect their relationships with other surgeons from the community, highlighting the potential impact on referrals. Finally, although not a dominant response, some expressed that avoiding judgement is simply a quality of being human.

“And then a little bit of it comes into also like anxiety of, okay, you know, are they going to potentially have some retaliation for this, and also on top of it is your reputation as a surgeon in the community, are people going to say, oh, he’s kind of, reckless as a surgeon because he had a complication?”

(ID 4)

Factors Influencing Intensity of Responses

In addition to reporting the variety of emotions and sources of emotions, participants described multiple factors as influencing the intensity of those responses. The type of complication, surgeon’s experience level, and surgeon’s individual personality were identified as some of the more salient factors impacting strength of response (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Variation in Intensity of Feelings

| Type of complication |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Experience level |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Individual differences between surgeons |

|

| |

|

Type of Complication

Participants asserted that the nature of the complication influenced their emotional response after an unwanted outcome. Elements such as the urgency of the case, the risk of complication relative to the actual outcome, the age and baseline health of the patient, and the severity of the postcomplication impact to the patient were some of the factors informing how a participant responded to a postoperative complication. Notably, complications that were perceived to be due to surgeon error were reported to be more difficult to process.

“So certainly, technical problems, but there’s also judgment factors. And then there are certain complications that happen that I feel like are not due to fallings down in judgement or technical or clinical care. They’re just unfortunate things that happen to the patient postoperatively. And those feel pretty bad too, but they’re not as worse as the first 2 categories.”

(ID 11)

Experience Level

Participants described how their experience level influenced how they responded to postoperative complications. For some, these events were more difficult to cope with as a resident or earlier on in their career. The most common explanation given for this was that as surgeons advanced through their careers, they gained more exposure and experience in navigating such challenging situations. Participants also described feeling unsure of the influence of their role, specifically during residency, making it difficult to voice their concerns and execute decisions that they thought were in the patient’s best interest. For others, the burden of responsibility became greater as they advanced through their careers. Participants voiced that due to the nature of residency as a fast-paced environment with relatively short-term relationships formed with each patient, residents lacked accountability for the continuation of a patient’s individualized care that attendings were largely responsible for. Finally, for many participants, the cumulative effect of experiences over time made the burden more difficult to carry. “I would say, when I first started in practice, ignorance was bliss, you know. I think you’re just younger. You’re immature in your professionalism. You’re transitioning from the resident role to the staff role, you know. And you’re, I don’t know if you ever heard about the surgeon’s personal graveyard… You know, your graveyard is empty. And I think as the years go and you kind of find all the different ways, you know, you can screw up, and you also don’t want to revisit past mistakes, which, of course, you do sometimes. So, I think that’s kind of the process.” (ID 23)

Individual Personality

The individual personality of the surgeon also factored into the intensity of responses after a postoperative complication. Participants described this to particularly affect decision-making, with some surgeons expressing a desire to try everything despite a low likelihood of achieving a desired outcome, whereas others realized there was no remaining appropriate intervention for a patient. Other participants described how individual personality may impact commitment levels – with some feeling that excessive commitment to the patient could have deleterious implications on surgeon wellness, and asserted a desire to avoid this. “Some surgeons are very connected with patients on a psychological level. Some are, you know, it’s more in a technical thing. I did the surgery. Sorry that happened. We’ll do this. Bye. You know, I tended to be more connected with my patients, and so I could feel some of their psychological pain when the postoperative course was altered and different than what they expected. And so that would, it would bug me.” (ID 15)

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate how the varied and profound emotional responses that surgeons face after postoperative complications impact surgeon well-being, or lack thereof. In this study, surgeons described feelings of sadness, anxiety, frustration, grief, failure, and disappointment, stemming from both internal processes and external pressures. Furthermore, the intensity of these responses was found to be incredibly complex and influenced by interconnected factors, including the type of complication, experience level, and the individual personality of the surgeon.

In 1979 Charles Bosk published a seminal ethnography offering a compelling and useful narrative in understanding the variety and response to errors that are made in surgical and medical training.10 Breaking down errors into the categories of technical, judgmental, normative, and quasi-normative, Bosk suggested that for residents in training, errors that were technical or involved judgement could be forgiven as it was expected that these were skills that could be improved with time. Normative errors; however, implied that the surgeon had failed in the conscientious discharge of their duties and signified a more problematic concern of the surgeons character. This work provided a groundbreaking perspective on the ways in which surgical education inculcates a deep professional ethic of personal responsibility. Surgeons judge errors and complications according to this framework of accountability they acquired as trainees. It could be argued that not only are these insights still relevant, the changes that have occurred in medicine since this book was published (eg, managed care, decline of professional authority, the rise of bioethics), could be of even greater significance now. In focusing on practicing surgeons, our work sheds light on the profound impacts that these events can have not only during medical training, but throughout a surgical career.

More recent work from researchers at the University of Toronto describes “the kick, fall, recovery, and long-term impact” phases, where the cognitive and emotive spaces surgeons move through following adverse events is described.6 This important and seminal work is an important first step to characterizing surgeons’ reactions to adverse events and their impact on subsequent judgement and decision-making. Our findings expand on this work and offer insight into other elements that could potentially be contributing to these emotional responses after a complication, such as payment systems and the litigious United States medical system.

In a culture that thrives on the principle of “do no harm,” there may be tension between the typical stereotype of a surgeon – who is often idealized as strong, unemotional, and lacking introspection – and the reality that complications can be powerful emotional experiences for all those involved.16 Previous research has suggested that oftentimes, surgeons believe they should neither make mistakes nor experience emotional responses when they do.1,17 Our research extends and expands upon that, demonstrating that for some surgeons, it is not just errors, but also complications in which the surgeon may not be at fault that have the potential to negatively impact overall well-being. Although the type of complication undeniably influences the intensity of the response, participants described how adverse events that were not due to surgeon error had the potential of causing feelings of guilt, anxiety, shame, and loss of self-confidence, which may contribute to the high rates of alcohol use disorders, depression, and suicidal ideation in this population.2,18,19

Participants pointed to aspects of surgical culture that trained surgeons to be confident and infallible, and often highlighted that the intrinsic nature of a surgeon is to want to fix things. Surgeons frequently encounter patients when they are at their most vulnerable and often bear the responsibility of containing the patient’s fear of death.16 Due to the high stakes involved, patients and their families often have a need to see surgeons as infallible, and the surgeon often colludes with them to deny the existence of error.20 Experiencing an unwanted or unexpected outcome, then, complicates that narrative in an environment that continues to stigmatize those that do not fit the idealized surgeon image.

Although the topic of emotional well-being is undeniably complex, our data suggest that internal processes are at least partially driven by external pressures, suggesting a need for a more open discussion around complications and their effects on surgeons, in such a way that moves beyond what only the patients and families feel and experience. Building on scholarship that calls for the need for a culture shift to accept humanity within surgical environments, our data suggest a need for changing the narrative surrounding self-doubt and complications early on in one’s career trajectory to normalize these processes for younger surgeons.10,21–23 Further, this research suggests the need to destigmatize processes that act as roadblocks for cultivating a culture that accepts help-seeking to provide experienced surgeons with the resources they need to cope with the burdensome accumulation of a lifetime of complications.

There were limitations to this study which should be addressed. The limited number of studies exploring surgeons’ emotional responses to postoperative complications and death are just beginning to emerge. Exploring emotional responses is a deeply personal topic and it is unknown whether surgeons experiencing burnout or apathy are less likely to participate in our study; however, the richness and vulnerability of the responses we received indicate that this may be an area where surgeons want to share their experiences and participate in conversations regarding their emotional responses. Although this study allowed for improved understanding of surgeons emotional responses to poor or unwanted outcomes, we acknowledge the limitations introduced by only including surgeons in the state of Michigan. Factors such as practice and geographical setting likely play a role in experiences with postoperative complications. Finally, given that a significant percentage of our sample were white men, it is difficult to know if these results will be generalizable in any way to surgeons who are women or from racially or ethnically diverse backgrounds.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest a need to place greater emphasis on addressing surgeons’ emotional responses after postoperative complications – including reducing the stigma surrounding feelings and facilitating discussion about ways of potentially offering new strategies of support – an issue that could potentially represent a threat to individuals and the profession altogether if allowed to remain inadequately recognized and addressed. As the body of literature on surgeon wellness continues to grow, there is a need for focused studies to tease out the potential difference in factors such as practice and geographical setting, surgical specialty, gender, race and ethnicity, and age. Additionally, to provide appropriate and effective programs to target these issues, there is a need to explore the various ways in which surgeons cope with these processes, including but not limited to a review of previous interventions and their perceived impact on surgeon wellness.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptualizing Emotional Responses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative for their assistance in facilitating these interviews and the surgeon participants for participating in the interviews.

This project was funded by the American College of Surgeons Thomas R. Russell Faculty Research Fellowship, the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract and Research Foundation of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Joint Faculty Research Award, and the National Institute on Aging Grants for Early Medical/Surgical Specialists Transition to Aging Research (GEMSSTAR) (R03 AG056588). PAS is also funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08 HS026772).

Footnotes

This work was presented as a podium presentation at the Society of Academic Asian Surgeons and received the award for highest rated abstract.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lander LI, Connor JA, Shah RK, et al. Otolaryngologists’ responses to errors and adverse events. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1114–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han K, Bohnen JD, Peponis T, et al. The surgeon as the second victim? Results of the Boston intraoperative adverse events surgeons’ attitude (BISA) study. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:1048–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCray LW, Cronholm PF, Bogner HR, et al. Resident physician burnout: Is there hope? Fam Med. 2008;40:626–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among american surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250:463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luu S, Leung SO, Moulton CA. When bad things happen to good surgeons: reactions to adverse events. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luu S, Patel P, St-Martin L, et al. Waking up the next morning: surgeons’ emotional reactions to adverse events. Med Educ. 2012;46: 1179–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn PM. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, et al. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18:325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel KG, Rosenthal M, Sutcliffe KM. Residents’ responses to medical error: coping, learning, and change. Acad Med. 2006;81:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosk C Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guest RS, Baser R, Li Y, et al. Cancer surgeons’ distress and well-being, I: the tension between a culture of productivity and the need for self-care. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1229–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, et al. Development of a list of high-risk operations for patients 65 years and older. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weingart SN, Lezzoni LI, Davis RB, et al. Use of administrative data to find substandard care: validation of the complications screening program. Med Care. 2000;38:796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care. 1994;32:700–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12:297–298. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold-Forster A Operating with feeling: emotions in contemporary surgery. Bull R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penson RT. Medical mistakes: a workshop on personal perspectives. Oncolo-gist. 2001;6:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147:168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. Br Med J. 2000;320:726–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balch CM. Stress and burnout among surgeons. Arch Surg. 2009;144:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg RM, Kuhn G, Andrew LB, et al. Coping with medical mistakes and errors in judgment. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wears RL, Wu AW. Dealing with failure: the aftermath of errors and adverse events. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]